Late bronze age petroglyphs of Unyuk mountain, in the Minusinsk basin

Автор: Esin Y.N., Skobelev S.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145479

IDR: 145145479 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.1.072-080

Текст обзорной статьи Late bronze age petroglyphs of Unyuk mountain, in the Minusinsk basin

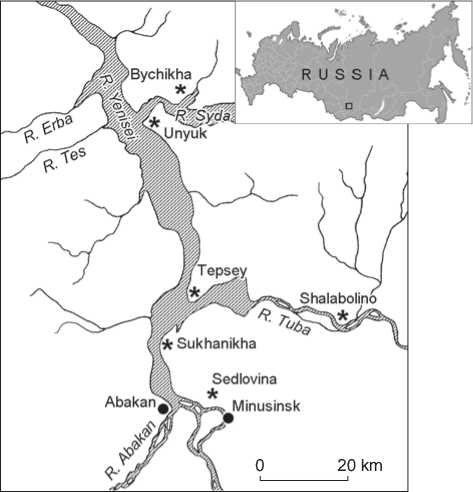

The Minusinsk Basin is the area containing many rock art sites. The majority of rock art sites are located on the sandstone outcrops along the banks of the Yenisei and its tributaries. The first information about these localities became available as early as in the 17th century, and special studies were carried out throughout the 19th– 20th centuries. However, despite the long history of study, there are still opportunities to discover new rock art sites providing additional information on the culture of the local population. The petroglyphs on the Unyuk Mountain on the right bank of the Yenisei, upstream of the mouth of the Syda River, are among the recently discovered sites (Fig. 1). Currently, this is the Krasnoturansky District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory. The present authors carried out a survey and studies of the petroglyphs in the summer 2016 and spring 2017. This paper introduces the petroglyphs and describes their stylistic features, age, and compositions.

Description of the site

The Unyuk Mountain is the highest peak on the right bank of the Yenisei, south of the Syda’s mouth. The area is rich in archaeological sites of various types and ages. These include a multilayered settlement on the bank of

Fig. 1. Unyuk and other rock art sites on the right bank of the Yenisei River.

the Yenisei, with impressive materials from the Neolithic period and the Tashtyk culture; the Tagar and medieval kurgans; and a fortress with ramparts and moats on the mountain (Zyablin, 1973; Skobelev, Ryumshin, 2015). The area was densely populated in the past.

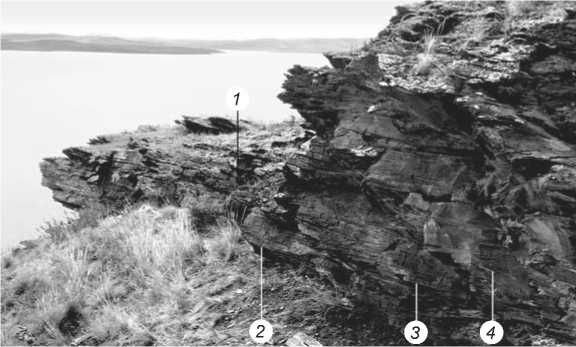

The mountain contains several ravines; the eastern slope is partially covered with pine forest. The western and southern slopes are formed by the rock outcrops, steeply coming down to the Yenisei (currently, the Krasnoyarsk water reservoir). The top of the scarp is about 100–120 m above the water level. These rocks are only partially visible from adjacent areas of the mountain top; they look hard-to-reach, heavily damaged, and unsuitable for making petroglyphs. But the site containing petroglyphs is located exactly on the upper tier of these cliffs (Fig. 2, a ). It offers a good view of the Yenisei River

а

b

Fig. 2. The rock art site on the Unyuk Mountain.

a – view on the mountain from the western bank of the Krasnoyarks water reservoir (the arrow points to location of the petroglyphs). Photo by S.G. Skobelev; b – general view on the rock tier containing petroglyphs, from the southeast (numerals designate numbers of panels). Photo by Y.N. Esin.

valley. The most convenient approach to the petroglyphs is from inner ravine on the northwestern slope, where ancient settlements could have been situated, invisible from the Yenisei and Syda, and protected from the predominant western winds.

The petroglyphs are located on a small part of the rock’s upper tier, on four panels over the scarp (Fig. 2, b ). Rock outcrops of this tier are composed of reddish-brown sandstone, partially covered by light whitish accretions. The outcrops are stretched along the SW-NE line, with a slight elevation towards the northeast (to the top). The panels with petroglyphs face southeast. The central part of the site can be considered panel 3, under a large natural rock shelter, containing the largest number of rock images. At the bottom of some of the panels, there are niches.

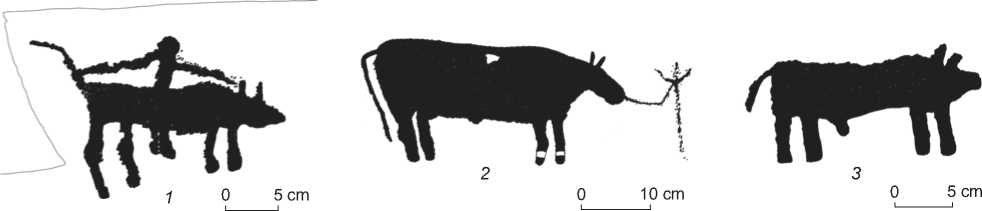

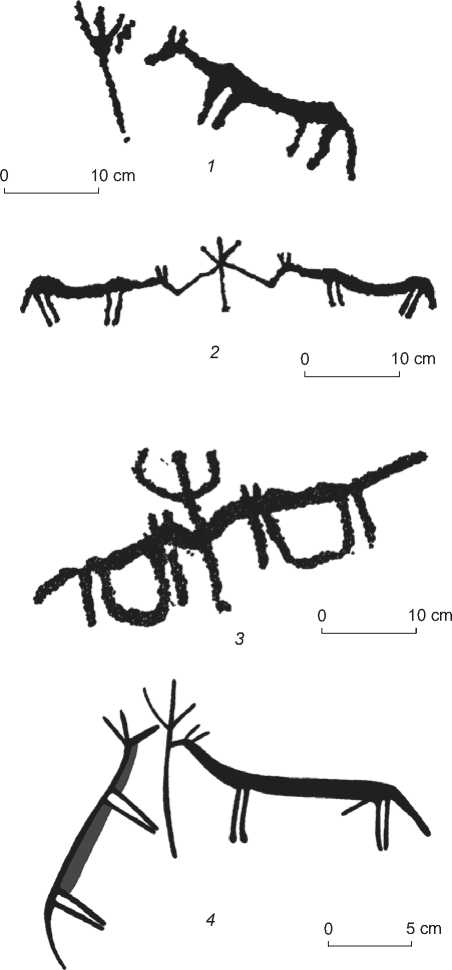

Panel 1. This is the westernmost point of the site. The pass leading to other panels in the northeastern part of the site runs along the tier of rock exposures. Panel 1 is about 50 cm long and 34 cm high. It dips at an angle of about 20°. Over the panel, there is a small overhang 36 cm long. The overhang is 78 cm above the ground. In front of the panel, at the bottom of the rock tier, there is a ledge about 1 m wide (below the ledge, to the northeast of it, there is a deep scarp). The rock image is situated 25 cm above the ground. The roughly pecked image (19 × 9 cm) shows an ox with its head to the right. Four legs and two ears (or short, schematically rendered horns) are represented. Possibly later, an image of a mounted man was added on the ox’s back. One of his arms is stretched forward; another, probably with a whip, is turned backward; his leg hangs down below the ox’s belly. Probably simultaneously with the depiction of this mounted man, the ox’s hind legs were also extended (Fig. 3, 1 ).

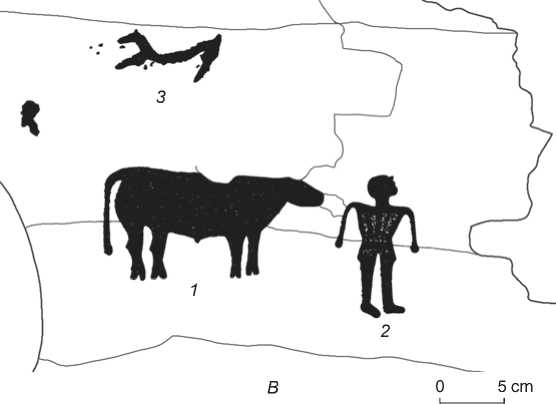

Panel 2. This panel (60 × 83 cm, inclination about 30°) is situated 4 m to the northeast of panel 1. Over it, there is a small overhang 30 cm wide. The overhang is 1.15 m above the ground and 0.5 m above the bottom edge of the panel. Below the panel, there is a niche about 0.5 m deep; a ledge about 0.8 m wide is in front of the niche. The panel contains two pecked images.

The main image on the panel is located in the upper part. This is a large figure of an ox (37.5 × 17.0 cm), with its head to the right. Four legs, a long tail, two ears, and a protruding preputial cavity are shown. A rope runs from the ox’s nose forwards and up, where it is tied to a vertical pillar (14 cm high) with a triple top (Fig. 3, 2).

The lower right portion contains another ox image (22 × 10 cm), oriented in the same way as the previous one (Fig. 3, 3 ). This image is smaller and more schematic, but shows the same main features, with a shorter tail.

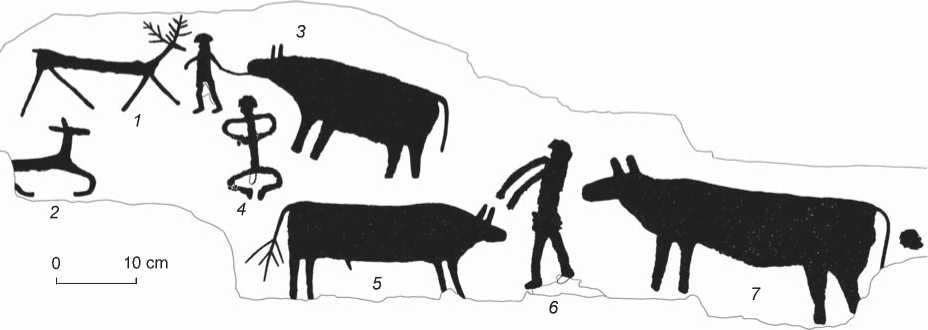

Panel 3. This panel (1.3 × 83 cm, inclination about 30°) is situated 3.6 m to the northeast of panel 2. Over it, there is a large overhang, projecting to 1.2 m. The overhang is 2.5 m above the ground and 0.95 m above the bottom edge of the panel. Below the panel, there is a niche about 0.6 m deep; a ledge about 1.5 m wide is in front of the niche. The panel contains several pecked images (Fig. 4).

In the upper left part of the panel, a deer (21.5 × × 12.0 cm) is shown, with its head to the right. The deer’s body is narrow, long, and rectangular, the four legs are placed apart as if running fast, the neck is stretched forward and up, the head has two branching antlers (Fig. 4, B , 1 ). Below this image, there is a roughly pecked and poorly preserved figure of an ungulate (13.5 × 9.5 cm), with its head to the right; the animal is shown with its legs bent under its body (Fig. 4, B , 2 ).

To the right of the deer, there is an image of a man (13.5 × 4.8 cm) leading an ox on a rope (25.6 × 12.5 cm), both moving leftwards (Fig. 4, B , 3 ). The man’s body is shown in frontal view, with his arms down at the sides of his body; his legs are shown in side view, with the forefeet to the left. The head is topped with a mushroom-shaped headgear. With his hand, the man holds the rope attached to the nose of the ox, shown with four legs, a long tail, and two ears or horns.

To the right of the image of ungulate with bent legs, an anthropomorphic figure (12.6 × 6.8 cm) is shown, with a rounded head, a body in the form of a vertical straight line, arms bent at the elbows and oriented to the body, and legs bent at the knees in a sitting pose, with marked feet (Fig. 4, B , 4 ). Below this image, a figure of an ox is pecked (32 × 12 cm), with its head to the right. The ox has four legs, two ears, a bushy tail (rendered through several divergent lines at the end), and a male

Fig. 3. Images on panels 1 ( 1 ) and 2 ( 2 , 3 ), Unyuk. Tracing by Y.N. Esin.

А

B

Fig. 4. Images on panel 3, Unyuk. Photos and tracing by Y.N. Esin.

sex organ (Fig. 4, B , 5 ). To the right of this figure, a man (18 × 10 cm) and an ox (36.2 × 16.0 cm) are represented, both moving to the left. The man’s body is shown in side view, with his arms turned down to the left from the body; his legs are slightly put apart, with the forefeet to the left (Fig. 4, B , 6 ). The ox image shows four legs, long tail, and two ears.

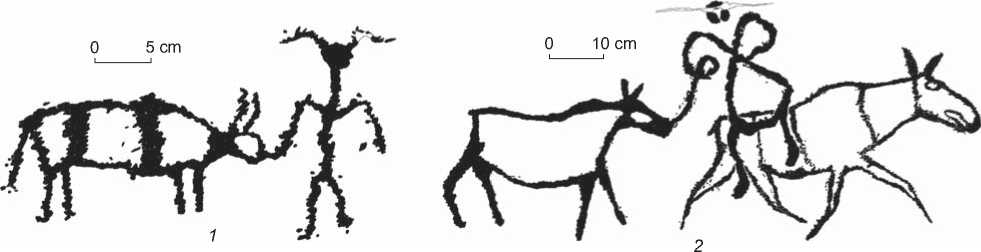

Panel 4. This panel (0.5 × 0.5 cm, inclination about 20°) is situated 0.5 m to the east of panel 3. Over it, there is an overhang, projecting to 1.2 m. The lower edge of the panel is located 1.15 m above the ground, the lower image about 1.4 m above the ground. Below the panel, there is a niche about 1.1 m deep; a ledge about 1.3 m wide is in front of the niche. The panel contains three pecked images (Fig. 5).

An ox figure (20 × 10 cm) is shown, with its head to the right. The ox has four legs with cloven hoofs, a long tail, and a preputial cavity; the upper part of the head did not survive (Fig. 5, B, 1).

To the right of the ox, a human figure (11.5 × 6.8 cm) is depicted. The body is shown in front view, with the arms turned down; the thickened ends represent hands. The legs are shown in side view, with the forefeet to the right. The head is also rendered in side view, with the face turned to the right and upwards; the nose and lips are shown, the neck is marked specifically. At the bottom of the body, there are small protrusions, possibly representing the lower edge of the jacket; vague lines within the body may show the jacket-breast and neck cut (Fig. 5, B , 2 ).

Over the ox image, there is an ungulate figure, with its head to the left (10.0 × 5.5 cm). The animal’s body and neck are rendered with a continuous curved line. Shown are two legs, stretched forward and down, an ear, and a small tail like that of a roe deer (Fig. 5, B , 3 ).

А

Fig. 5. Images on panel 4, Unyuk. Photos and tracing by Y.N. Esin.

Main images, their style and age

Bull (ox). In total, seven images portraying the relevant sub-family of bovids were recorded. In terms of quantity, this image is the main one at the site. Despite minor differences of detail, all the images are of similar style and belong to a single artistic tradition. The main features are a thick, sub-rectangular body, and a small head stretched forward or slightly down. The legs are shown with four vertical parallel lines. Judging by their peripheral location at the site and on panel 2, the most schematic images (see Fig. 3, 1 , 3 ) were apparently made later than more realistic and larger ones. Stylistic features of oxen images at Unyuk Mountain differ from those typical of the Okunev culture of the mid-3rd to early 2nd millennia BC, as well as from the earlier Minusinsk tradition, and from the known images of the Early Iron Age and medieval period. The closest parallels are known from the near-by site of Bychikha (on the right bank of the Syda River) and on the Tepsey Mountain (Kovaleva, 2011: Pl. 1, 2, 18). Consequently, the Unyuk images can be attributed to the Late Bronze Age. Notably, oxen images occur rather rarely among petroglyphs of that time, and figures with such bodies even more rarely. In the Late Bronze Age, in the Minusinsk rock art, there were several traditions for representation of animals, including oxen, which reflected the existing ethno-cultural situation (Esin, 2013: 74).

All depicted oxen apparently were hornless, which is a feature of a domesticated animal. This is also confirmed by the rope running from the nose in two figures. This is evidently a rope for controlling the animal: one of its ends is attached to the animal’s nose, another is shown either in the hand of the human or tied to a pillar. In the traditions of many pastoralist societies, the draft cattle that were controlled in such a way were usually gelded in order to reduce aggressiveness. Hence, all the depicted animals are bulls. This assumption does not contradict the fact that some of the figures show male sex organs. These animals might have been used for carrying carts, travois, load packs, and the like.

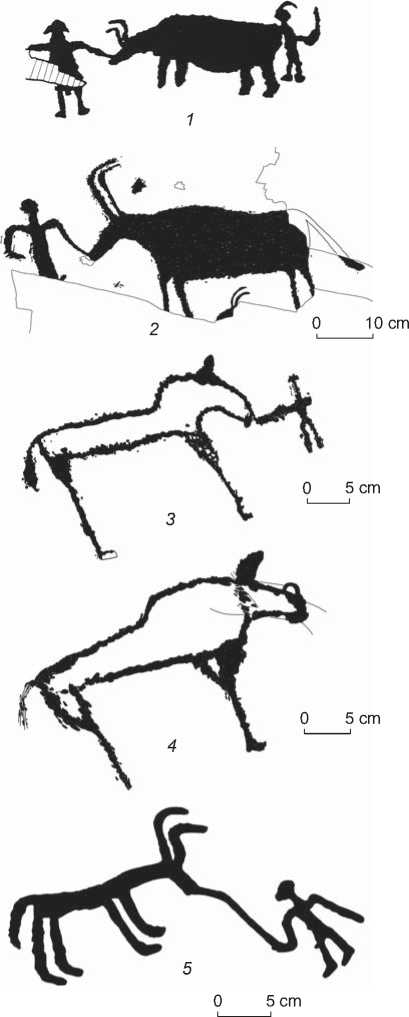

Representation of a rope fixed in the bull’s nose is typical of Okunev art; however, a wooden loop inserted into the animal’s nose is always shown, while the end of the rope runs between the animal’s horns or is tied around them (Miklashevich, 2003–2004; Esin, 2018a). Another type of composition, where the end of the rope is shown in the human’s hand, is represented in four petroglyphs on the Tepsey Mountain. Formerly, it was believed that one of them (Fig. 6, 1 ), showing an ox image of the Bronze Age, was later (in the Late Tagar period) supplemented with two human figures (Sovetova, 2005: 33, pl. 28, 11 ). However, only one human figure (behind the ox) can be dated to the Iron Age. The image of a man holding the rope is contemporaneous with the ox image. Stylistically, they are quite similar to petroglyphs on panel 3 of the Unyuk Mountain. Other types of oxen images with ropes at Tepsey (Fig. 6, 2 , 3 ) can be dated to the late 2nd to early 1st millennia BC. One of these bull images (possibly early 1st millennium BC) shows a large ring in its nose and presumably a rope tied around its horns (Fig. 6, 4 ). The shape of the ring is different from the Okunev wooden loops with crossed ends, and possibly represents a metal item. Another stylistic version of the image of an ox with a rope in its nose, the most schematic one, was pecked at the Sedlovina Mountain in the Late Bronze Age (Fig. 6, 5 ).

Two compositions from the central part of the Shalabolino rock art site are considerably younger

Fig. 6. Some images of oxen with a rope and a ring in the nose, in the rock art of the Minusinsk Basin.

1–4 – Tepsey; 5 – Sedlovina.

1 – after (Sovetova, 2005: Fig. 11) (no scale); 2–5 – tracing by Y.N. Esin.

(Fig. 7). Surprisingly, one of them shows a rope attached to the nose of the elk-figure executed in the Angara style. One end of this rope has a loop held by a woman (?), which image overlaps the elk image of the Early Bronze Age (riding on the elk’s back?) (Fig. 7, 2 ). The image of the woman holding the rope was possibly added during the medieval period (Zaika, Drozdov, Makulov, 2005); yet the exact age of these two compositions requires additional research.

Pillar. Of special interest is the image of a pillar, to which an ox is tied, at panel 2. The composition of “an ox at a pillar” is known in the Okunev art of the earlier period. However, the Okunev pillar was represented with a simple straight line. A pillar with a triple top is known only from petroglyphs of the Karasuk period (Fig. 8). These compositions usually show horses at the pillar. The horses are most often paired, and possibly represent a chariot team (Esin, 2018b). Such an image has been reported from a plate that served as a wall of the Karasuk tomb at the cemetery of Severny Bereg Varchi I (Leontiev, 1980). This can be considered another reliable argument supporting the age estimate for the Unyuk petroglyphs. The vertical line with two offshoots apparently represents the real wooden pole: the central line is a chopped-off tree trunk, and the side lines are the remains of two lower symmetrical branches. Judging by some of the images (Fig. 8, 1–3 ), the pole ends might have been additionally worked and rounded. The pillars were used for attaching draft animals, primarily horses, given the available range of images. The end of the rope was thrown over one of the remained side-branches.

In reality, a pillar for attaching animals could be established close to the dwelling. The pillar also had an important ritual meaning. The shape of the pillar’s top was determined not only by its suitability for attaching

Fig. 7. Images of animals with a rope in the nose, at the Shalabolino rock art site. Tracing by Y.N. Esin.

Fig. 8. Images of a pillar with triple top in the rock art of the Minusinsk Basin.

1 , 2 – Tepsey (after (Sher, 1980: Fig. 74, 124)); 3 – Sukhanikha;

4 – Severny Bereg Varchi I ( 3 , 4 – tracing by Y.N. Esin).

animals, but also by ritual-mythological perceptions connected with the number 3. For instance, in the art of the Kets, who inhabited the Altai-Sayan region in the past, the “shaman tree” was depicted with a triple top. It connected various tiers and parts of the universe (Alekseenko, 1967: Fig. 25). Y.A. Sher (1980: 267) argued for the ritual purpose of the Karasuk hitching post, which was represented at the Tepsey rocks.

Human. Five anthropomorphic images can be classified into three groups. Group 1 includes three rather realistic figures (see Fig. 4, B, 3, 6; 5, 2). The characteristic features are the marked feet, thickened arm-ends, and special headgear; they all are typical of the Late Bronze Age images in the Minusinsk Basin. One of these characters leads the ox on the rope; two other are represented without ropes, but also in front of the oxen, moving in the same direction with them and forming a single composition, rendering a similar meaning.

The fourth human figure is schematic and represents a sitting man, with his arms and legs bent (see Fig. 4, B , 4 ). The style of this image is different from that of the first group, but is also well-correlated with other Late Bronze Age images in the Minusinsk Basin, including the image on the slab of the Karasuk tomb (Sunchugashev, 1971: Fig. 1; Kovaleva, 2011: Pl. 91, 92).

The most debatable is the fifth human figure, with the arms spread apart, sitting on the ox’s back (see Fig. 3, 1 ). It looks as if it was added later, though the color of desert varnish of pecking is similar to that of the animal image. The leg of this character is lowered down below the ox’s belly. It should be noted that in the Late Bronze Age and in Tagar art, the leg of a horseman was not usually shown below the horse’s belly. Possibly the human figure was added in the late 1st millennium BC, though this issue remains open.

Deer. There is one image of a stag. The shape of the body (narrow, long, and sub-rectangular, with a small triangular projection at the shoulders), neck, head, and antler is similar to the style of the Late Bronze Age petroglyphs in the Minusinsk Basin (Kovaleva, 2011: Pl. 22, 104). Only the way of representing the legs is atypical—wide apart, in motion. This technique was specific for elk and deer images of the Early Bronze Age. In the Late Bronze Age, it could have survived as an anachronism.

Other ungulates . The figure of an ungulate animal with bent legs on panel 3 can be correlated with the schematic image of a sitting man on the same panel, and dated to the same period (Ibid.: Pl. 38, 65, 74). Another version of this style is represented by a figure of an ungulate with its legs stretched forward and down. It can possibly be dated to the Bronze to Iron Age transition period.

Conclusions

To sum up, it can be concluded that the main petroglyphs from the small rock art site at the Unyuk Mountain were executed in the Late Bronze Age. Their age can be estimated as the late 2nd to early 1st millennia BC. The images are not contemporaneous, and point to repeated human visits to this place. Noteworthy is the specificity of the Unyuk petroglyphs in terms of the set of images, style, and compositions, as compared to many other petroglyphic sites of the same age in this region.

The domesticated ox was the most important image for the creators of the petroglyphs. In one case, it is represented tied to a pillar of especial shape, which was likely used not only in household activities, but also for ritual purposes. This suggests that the scene was associated with animal sacrifice. The composition consisting of a man and an ox is repeated thrice, probably reflecting the very important part of everyday human life. Who these people are, and where they are going with their animals, is not clear, but it is noteworthy that the face of one character is turned up to the sky. This topic can be correlated with a chariot as the image of another means of transport of the Late Bronze Age. According to one hypothesis, in that period, the images of chariots in the Altai-Sayan were associated with burial rites and transition of dead to the nether world (Devlet, 1998: 183–185; Kilunovskaya, 2011: 44; Esin, 2013: 75). It cannot be excluded that the Unyuk images also show the deceased on their way to the nether world, but using another means of transport. Prior to the wide spread of horse riding in the Early Iron Age, oxen were commonly used as means of transport in mountain or forest terrain, unsuitable for wheeled vehicles. In Western Tuva, these means of transport survived till the early 20th century; in some highland regions of Asia (Tibet, the Pamirs, etc.) they are still common, but with the use of yaks and their hybrids. The safe journey of the deceased to the afterworld was very important for the relatives, who conceived of such a journey as a real trip. Some of the rock images were likely executed in the context of such beliefs and recurrent burial and funeral rites.

The role of the ox image is a distinctive feature of the Unyuk petroglyphs as compared to the typical Late Bronze Age rock images in the steppe part of the Minusinsk Basin, located mostly on the left bank of the Yenisei, in which the horse image played the main role. It is not surprising that the main parallels to the Unyuk petroglyphs were noted in the vicinity, on the mountains of Bychikha, Tepsey, and Sedlovina, on the right bank of the Yenisei. The specificity of this site can be explained by the echo of the Early Bronze Age tradition, which continued its development in the southeastern foreststeppe periphery of the Minusinsk Basin in the Andronovo period. Owing to environmental conditions, important economic (including transport) and ritual significance of oxen survived for a longer period here. This small local ethno-cultural substrate, with its original traditions, might have become one of the components of a new culture emerging in the Late Bronze Age.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the image of a man leading an ox on the rope, rare in the Minusinsk Basin, is rather typical of the Bronze Age petroglyphs in the southern regions of the Altai-Sayan. All these images can be regarded as versions of one type of scene—“man walking with an ox”. The main dispersal area of this composition includes mountain regions to the south and southwest of the Minusinsk Basin. This area is characterized by similar environmental settings and forms of economy, as well as some cultural similarities. Along with the general similarity in composition (and sometimes in headgear), there are also significant differences in particular elements and style. For instance, petroglyphs to the south of the Minusinsk Basin usually show passengers and load packs on the animals’ backs, with the animal often led by a woman (Devlet, 1990; 1993: Fig. 4, 4, 5; Kubarev, Tseveendorj, Jacobson, 2005: Fig. 89, 90, 10–12, 93, 4–8; Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 921, 980, 981). Such differences reflect the independent cultural development of the populations of either side of the large mountain ranges in the Altai-Sayan.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed under the basic part of the Research Public Contract. The authors are grateful to V.S. Makienko, researcher of the Museum of History and Ethnography of the Krasnoturansky District, Krasnoyarsk Territory, for the information on the locations of petroglyphs on the Unyuk Mountain.