Late middle and Early Upper Paleolithic in the Eastern Adriatic and the problem of the regional middle/upper Paleolithic interface

Автор: Karavanid I., Vukosavljevic N.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145427

IDR: 145145427 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.2.003-012

Текст обзорной статьи Late middle and Early Upper Paleolithic in the Eastern Adriatic and the problem of the regional middle/upper Paleolithic interface

The Adriatic region is of an extreme importance, owing to its geographic position, which connects the Mediterranean with the European continent, as is reflected in the rich archaeological record. In recent years, work on Mousterian sites in this region has intensified, and has provided important information about the chronology of habitation, adaptation, and behavior of Mousterian people. Unfortunately, very limited new information about the Early Upper Paleolithic was gathered by recent research. In this paper, Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic sites from the Adriatic region (Fig. 1) will be briefly presented, and the problem of the Middle/Upper Paleolithic interface will be discussed. The Adriatic region, including both sides of the modern Adriatic Sea and the Danube corridor, is very important in regard to the modern peopling of Europe (Chu, 2018). Here, we present currently available data from Croatia in the north down to Albania in the south.

1 - Romualdova pecina; 2 - Sandalja II and Campanoz; 3 - Ivsisce; 4 -Bukovac pecina; 5 - Open air-sites between Ljubac Bay and Posedarje;

6 - Velika pecina in Klicevica; 7 - Veli rat (Dugi otok Island); 8 - Gigica pecina; 9 - Stipanac; 10 - Mujina pecina and Karanusici; 11 - Kastel Stafilic-Resnik; 12 - Crvena stijena; 13 - Bioce; 14 - Blazi cave; 15 -Shën Mitri.

Overview of the Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic sites in the Eastern Adriatic

Northeastern Adriatic

Coastal areas . Several years ago, the Middle Paleolithic was discovered at two sites (Romualdova pecina and Campanož) in the Croatian part of Istria (Komšo, 2008, 2011). Romualdova pecina is located on the southern slopes of the eastern part at the end of the Lim Bay, northeast of Rovinj (Malez, 1979; Komšo, 2008). M. Malez (1979: 252) determined the industry from this cave to represent the younger Aurignacian and the early phase of the Gravettian. Judging by the presence of a shouldered point, the finds are most likely from the Early Epigravettian rather than Gravettian (Montet-White, 1996), or even from Late Epigravettian (Vukosavljevic, Karavanic, 2017). The determination of a part of the industry as Aurignacian is questionable. D. Komšo (2008) excavated the site in 2007 and found Mousterian artifacts. Recent archaeological work at this site has yielded the first radiometric dates (over 48 and 50 ka BP) for the Mousterian industry in Istria (Jankovic et al., 2017).

Another Mousterian site in Istria is Campanož, located in the open air near Medulin, not far from Pula.

Salvage excavations of 99 m2 recovered lithic material from a layer at a depth of about 50 cm below the surface (Komšo, 2011). A large lithic assemblage (more than 30,000 specimens), with frequent debitage items, strongly suggests that the site was a workshop. No faunal remains were recovered.

The Early Upper Paleolithic in this region is represented only by one cave, and maybe one open-air site. The cave site is Šandalja II, located near Pula, and it contains Upper Paleolithic (Aurignacian – E, F, G, and H complexes, and Epigravettian – C and B complexes) lithics, and faunal and human (Epigravettian) remains (Karavanic, 2003; Jankovic et al., 2011; Karavanic et al., 2013). Layers G, F, and E have provided radiocarbon dates between ca 32 and 27 ka cal BP, while the results obtained for level H do not fit chronologically into the dated stratigraphic sequence (see (Malez, Vogel, 1969; Srdoc et al., 1979)). However, a new date on a bone sample from level F indicates that all the old dates are too young (Richards et al., 2015). A small split-base osseous point was found in Level H, while in the lithic industry of this level and the H/G interface, only one lithic implement might be considered as an Aurignacian tool type. However, layers G, F, and E, including the E/F interface, contain an Aurignacian lithic industry and some osseous tools (Karavanic, 2003; Cujkevic-Plecko, Karavanic, 2018). Flakes are the most common lithic element in these deposits, although blades and bladelets are also represented. A very small percentage of tools could be explained either by their production elsewhere or, alternatively, people could have taken them from the site. Nosed and carinated end-scrapers are quite common, while Aurignacian blades are missing. Side-scrapers and notches are present in significant quantities. Dufour bladelets are missing from the sample, but it is not clear whether this reflects the real situation at the site, or the fact that the sediment was not sieved. The most common osseous tools in these units are awls. Four pierced animal teeth from the Aurignacian layers represent decorative items, and suggest symbolic behavior.

Ivsisce is an open-air site yielding surface finds, located at the rims of the Cepic polje, in the southeastern part of Istria. Judging by their technological and typological characteristics, these finds could be attributed to the Early Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic (Komšo, Balbo, Miracle, 2007). Although no cultural layers have been preserved, this is potentially the first Early Upper Paleolithic site (possibly Aurignacian) to be found in Istria since the discovery of Šandalja II, and the first Early Upper Paleolithic open-air site in this part of Croatia.

Hinterland. Another interesting site from the Early Upper Paleolithic period is Bukovac pecina, located in Croatia’s Gorski Kotar region, southeast of the town of Lokve (Malez, 1979). An osseous point from this site, discovered more than 100 years ago, was probably massive based (Mladec-type point), and can be attributed to the Aurignacian (Ibid.), as is supported by radiocarbon dating made on animal bone that originate from the same layer as the osseous point. The proposed age for the Bukovac bone point is ca 34,000 cal BP. The bone point (found inside the cave) and stone flake core (found in the trench in front of the cave mouth) are the only evidence of human activity on this site, representing chronologically and spatially discrete episodes of human presence. The flake core was found in the layer dated between ca 44,000 and 42,000 cal BP, placing it during the course of MiddleUpper Paleolithic transition. Core morphology could suggest its attribution to the Upper Paleolithic, although a Middle Paleolithic attribution cannot be excluded (Jankovic et al., 2018). In the absence of other diagnostic material, both attributions could be taken into the account.

Central Eastern Adriatic

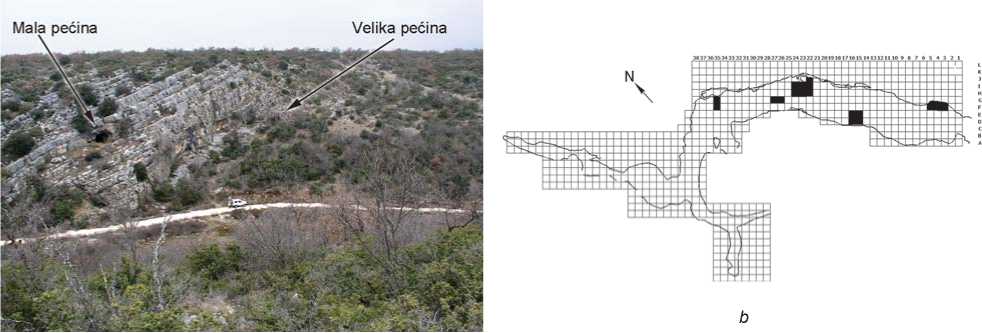

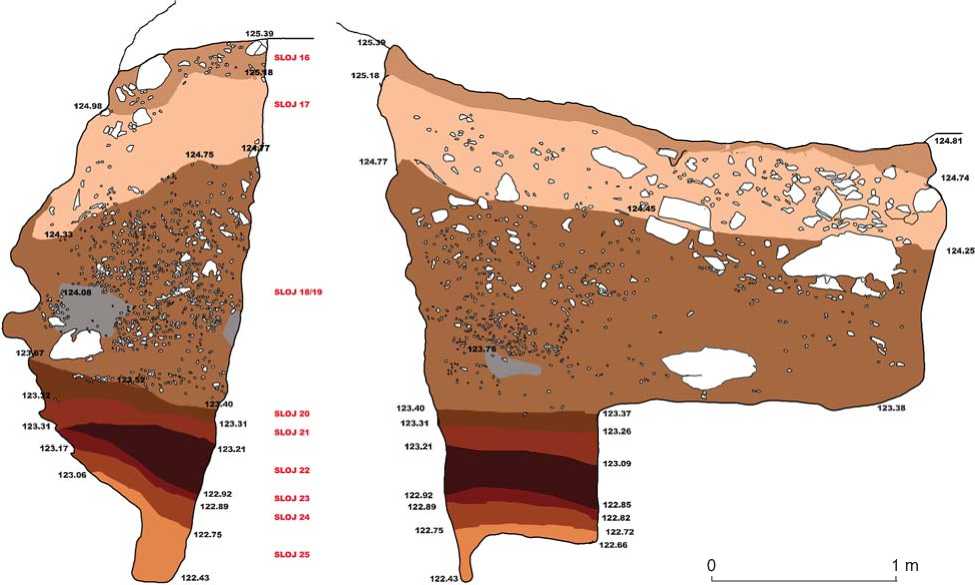

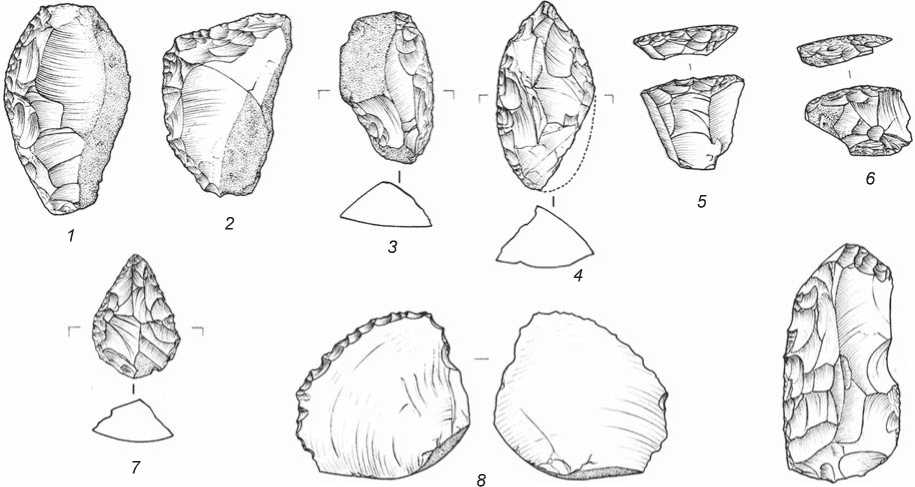

Coastal areas . Several important Middle Paleolithic sites are situated in Dalmatia. Velika pecina lies in the canyon of the Klicevica brook, near Benkovac, in northern Dalmatia (Fig. 2, a , b ). Animal bone from level D was dated by radiocarbon AMS to ca 43 ka cal BP (Karavanic, Condic, Vukosavljevic, 2007). Another animal bone from layer D (cut into two pieces) yielded two results: ca 39.7 ka cal BP (Beta-372935) and 36.5 ka cal BP (Beta-372934) (Karavanic et al., 2014). However, a result of ca >48 ka BP (OxA-33732) was yielded for stratigraphic unit 20 (trench near entrance), while level C (trench inside the cave started in 2006) was dated to ca 40.8 ka cal BP (OxA-33654) (for other dates see (Karavanic et al., 2018)). The dated bone sample (OxA-33732) from stratigraphic unit 20 is consistent with the result of U-Th dating of flowstone, and probably represents the real age of the dated stratigraphic unit* (Fig. 3). Obtained dates suggest that Mousterian humans visited the cave for the first time around or before 50,000 years BP, and were also present there later, during the time of the Middle/Upper Paleolithic transition, around 40 ka cal BP. The tools are small (as in the so-called Micromousterian) and made of local chert. Among the tools, diverse side-scrapers are present, and among these, microlithic transverse scrapers are remarkable (Fig. 4). Animal bones and teeth from Middle Paleolithic levels are less common than artifacts. Although some finds (pottery) from later periods were found, there is no single find suggesting an Upper Paleolithic affiliation. Velika pecina is the cave site geographically closest to many open-air sites in the Ravni kotari area, and on islands, which makes it very valuable for comparisons with those sites.

S. Batovic (1973, 1988, 1993) found Mousterian artifacts on Dugi otok Island and Molat Island. A large number of stone artifacts, and also debris, were gathered near the lighthouse on Veli Rat in the northern part of Dugi otok Island (Malez, 1979; Batovic, 1988). The lithic finds were attributed by Malez (1979) to the Mousterian (Middle Paleolithic) and Aurignacian (Early Upper Paleolithic); but later analysis based on material gathered by Malez, did not demonstrate the presence of Aurignacian-type tools (Hinic, 2000). This site should, therefore, definitely be attributed to the Middle Paleolithic, while the attribution to the Early Upper Paleolithic remains doubtful. Recent field surveys of Veli Rat confirmed the earlier attribution of found lithic scatters based on techno-typological grounds. In addition to old positions, some new surface lithic scatters are also found. Old and new data from Veli Rat suggest that majority of surface lithic finds belong to the Middle Paleolithic; but Upper Paleolithic and/or Mesolithic remains are also present (Krile, Vujevic, 2017).

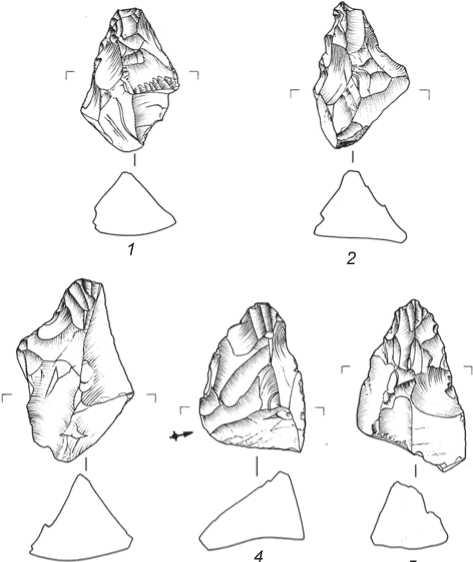

In the area between Ljubac Bay and Posedarje, north of the town of Zadar, there is a large concentration of Paleolithic open-air sites (Fig. 2, e , f) (Vujevic, Perhoc, Ivancic, 2017). S. Batovic (1965) collected numerous finds there. They are designated with the name of the specific area where they were found (for example, Radovin, Slivnica, Jovici). The sites yielded mostly finds from the Middle Paleolithic, but there are also some younger artifacts. Judging by their typology, some of the assemblages could represent the Charentian type of Mousterian (Vujevic, 2007). The industries from these sites are similar to those of other Mousterian sites of the Eastern Adriatic region. The tools are usually small, as in the so-called Micromousterian, and denticulates and notched pieces are frequent. However, an especially important place is held by nosed/carinated end-scrapers, collected by Batovic in the Radovin-Dracice site. Artifacts of the same type were found by D. Mustac not far from St. Peter’s Chapel*. These types of artifacts belong to the Aurignacian, and are very rare in this region (Fig. 5).

Z. Brusic (1977) collected a number of lithic artifacts near the islet of Stipanac in Prokljansko Lake, near Skradin (north Dalmatia), at a depth of 3 m, assigning them to the Mousterian industry. Centripetal (probable Levallois) core confirms this attribution, but it is quite possible that some of lithic material is from later periods. Therefore, Stipanac is the first underwater Middle Paleolithic site discovered in Dalmatia.

Other Mousterian sites come from central Dalmatia. Mujina pecina lies north of Kastela, close to city of Split (Fig. 2, c , d ). Chronometric dating (radiocarbon and electron spin resonance) has demonstrated that the

*Opinion of J. Hellstrom and P. Bajo, given in personal communication.

а

d

f

Fig. 2 . Middle Paleolithic sites in Dalmatia. Photo by N. Vukosavljevic ( a ) and I. Karavanic ( c-f), drawing by M. Vukovic. a - Velika pecina in Klicevica, general view from southeast; b - plan of Velika pecina in Klicevica (plan drawing by Ivan Condic, modified after (Karavanic et al., 2016)); c - Mujina pecina, general view; d - view from Mujina pecina towards Kastela Bay; e - view from Ravni kotari area towards Velebit mountain; f – open-air site Radovin.

Fig. 3 . East (F 2/3 line; left) and south (E/F 3-5 line; right) profiles of the trench near the cave mouth. Remains of dated flowstone are visible between layers 17 and 18/19. Drawing by R. Marsic.

5 cm

Fig. 4 . Selected stone tools from Velika pecina in Klicevica. Trench near the cave mouth. Drawings by M. Roncevic.

1 , 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 9 – side-scrapers; 4 – limace; 7 – convergent side-scraper / point; 8 – raclette on Janus flake. 1 – layer 20; 2 – layer 23;

3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 9 – layer 22; 5 , 8 – layer 21.

Fig. 5 . Nosed and carinated end-scrapers (surface finds from the Radovin-Dracice open-air site). Drawings by M. Roncevic.

Mousterian sequence of Mujina pecina can be attributed to a period between approximately 49 and 39 cal ka BP (Boschian et al., 2017; Rink et al., 2002). Traces of all the phases of stone tool production are present. The tools were largely made from local raw materials (chert). Centripetal cores are presented. The most frequent types of tool in the upper levels are retouched flakes and denticulates/notched pieces (Karavanic et al., 2008); but in the lower levels, scrapers are much more frequent than in the upper (Šprem, 2016). The tools are generally small, and strongly resemble the so-called Micromousterian. Along with stone artifacts, many faunal remains were also found in Mujina pecina. In the upper levels, Preston T. Miracle (2005) has identified unambiguous traces of human activity (damage caused by breakage, cut marks, burn marks) on the bones of chamois, ibex, red deer, and large bovines—aurochs and steppe bison. The fact that the remains of red deer, chamois, and ibex in Mujina pec ina are mostly those of adult animals, and that they bear traces of the butchering of carcasses, indicates the important role played by hunting in the life of the Mujina pecina Neanderthals (Ibid.; Karavanic et al., 2008). The oldest levels (E3, E2, E1) at Mujina pecina are the richest in human-related finds, indicating much more intense human activity than in more recent levels. The lower density of finds in the upper levels (B, D1, and D2)

suggests that the site was used as an occasional hunting camp during formation of these levels (Nizek, Karavanic, 2012). No Upper Paleolithic components were found in the stratigraphy of this site.

Not far from Mujina pecina (approximately 1 km south), at an open-air site near the village of Karanusici, some lithics were collected from the surface by I. Šuta, after M. Katic’s initial discovery of the site (Karavanic et al., 2018). This lithic assemblage exhibits clear elements of Middle Paleolithic, but also of later periods, pointing to the conclusion that material from different periods of prehistory is present here. A trial archaeological excavation was carried out at Karanusici in 2014 (Karavanic et al., 2016), in a trench measuring 2 m2 (2 × 1 m), positioned at the place where the densest cluster of stone artifacts was found on the surface during the previous field survey. The excavation yielded potsherds and stone artifacts; however, not a single stone find could be attributed undeniably to the Middle Paleolithic, even though this period was determined on the material that was previously collected from the surface (Fig. 6, 2 ).

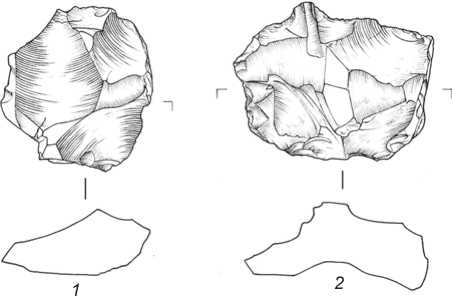

The number of artifacts with clearly Mousterian typological features was also collected from the underwater site of Kastel Stafilic-Resnik, which lies at a shallow depth of about 4 m (Karavanic et al., 2009). Centripetal cores (Fig. 6, 1 ) are presented in the lithic assemblage (Karavanic, 2015), in which side-scrapers are the most common tools (Barbir, 2015). Some Upper Paleolithic cores were also collected, but no single artifact that might suggest an Early Upper Paleolithic (Aurignacian) affiliation.

Hinterland . All these sites are on the territory of modern-day Croatia. However, north of the described central Dalmatian sites, another Middle Paleolithic site containing Mousterian lithics, Gigica pecina, is located in Bosnia and Herzegovina, near the town of Bosansko

0 5 cm

Fig. 6 . Middle Paleolithic centripetal cores. Drawings by M. Roncevic.

1 - underwater site Kastel Stafilic-Resnik; 2 - open-air site Karanusici.

Grahovo (Kujundzic, 1989). Although Z. Kujundzic (Ibid.: 12) attributed tools discovered in the upper part of layer IV to the Upper Aurignacian, it seems that there were no typical Aurignacian tools, and thus it is possible that these tools are attributable to the Epigravettian instead of the Aurignacian (Karavanic, 2009). The other sites are located further south-east.

Southeastern Adriatic

Hinterland . Crvena stijena and Bioce rock-shelters located in Montenegro provide a certain amount of information related to the Middle/Upper Paleolithic interface in the Eastern Adriatic (Derevianko et al., 2016, 2017; Dogandzic, Duricic, 2017; Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017). Crvena stijena layers XVIII–XII are attributed to the Late Middle Paleolithic (Dogandzic, Duricic, 2017; Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017; Mihailovic D., Mihailovic B., Whallon, 2017). A series of radiocarbon, ESR, and OSL dates place layers XIII–XII between ca 49 and 42 ka cal BP (Mercier et al., 2017). The final Mousterian of Crvena stijena is characterized by the presence of Uluzzian elements in the lithic assemblage (laminar and microlaminar technology, diverse reduction strategies employed in flaking flakes and splintered pieces, and backed tools, including segments and arched points).

The upper layers of the Bioce rock-shelter are supposed to be of MIS 3 age, which is supported by radiocarbon dates that date the accumulation of layers 1.2 and 1.4 between 40 and 32 ka BP (Derevianko et al., 2016, 2017; Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017). Given the small sizes of tools from layer 1, A.P. Derevianko et al. (2017) refer to this layer’s assemblage as Micromousterian. Both Middle and Upper Paleolithic technological and typological elements are present in upper layers (Dogandzic, Duricic, 2017; Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017). The presence of Middle and Upper Paleolithic elements in Crvena stijena could be explained as continuity in the evolution of lithic industries, when considering its Late Mousterian and Uluzzian elements (Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017). Unfortunately, Early Upper Paleolithic sites in the Southeastern Adriatic hinterland are so far unknown, which prevents a more comprehensive understanding of the Middle/Upper Paleolithic interface.

Coastal areas . In the Albanian archaeological record, until recently, when Hauck et al. (2016) reported on a layer from Blazi Cave (layer 4), which is ca 45 to 43 ka cal BP old, there were no sites dated to Late Middle Paleolithic and Early Upper Paleolithic. Lithic artifacts from layer 4 from Blazi Cave are very few and undiagnostic. Hauck and colleagues also report the probable Aurignacian age of several carinated cores and thick end-scrapers discovered in the open-air site Shën Mitri, in southern

Albania. The context of lithic finds there was affected by various taphonomic factors as is visible in the association of Holocene radiocarbon dates and lithic assemblage of probable Upper Paleolithic age.

Discussion and conclusion

In the last 20 years, research on the Late Middle Paleolithic has been conducted in the Eastern Adriatic with different intensity in different regions. Therefore, the Late Middle Paleolithic is relatively well explored and known, and discussed in the literature. On the other hand, Early Upper Paleolithic sites in the same region are scarce, while in particular, sites from the Early Aurignacian are completely lacking. AMS dates give a good temporal frame for the Late Middle Paleolithic. In contrast, radiocarbon dates for the Early Upper Paleolithic are scarce, and were made long time ago, hence bringing into question their reliability, as is supported by their very late age for the Aurignacian. Only one recent AMS date from Šandalja II could represent the real Aurignacian age. There is a hiatus of several thousand years between the Late Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic in this region, and no industry from a single site shows a progressive or transitional nature, with the exception of Crvena stijena. Moreover, sites with stratigraphy encompassing both the Late Middle Paleolithic and the Early Upper Paleolithic have not yet been found.

The reasons for such a fragmentary record of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition could be multifold: relatively short and unsystematic research on the

Paleolithic in the region;

paleoenvironmental change, i.e. a rise in sea-level probably destroyed potential sites;

low population density during the Early Upper Paleolithic;

no temporal overlap between Late Neanderthals and Early modern humans;

lack of stratified sites encompassing Late Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic remains.

However, the most acceptable explanation, proposed by D. Papagianni (2009: 133), is that Neanderthals may have disappeared from this region before modern humans arrived; see also (Papagianni, Morse, 2013). It may be that this chronological gap in the habitation of these two groups of humans was caused by various factors that could have made this region difficult for human habitation for some time: among these, the volcanic eruption of Campanian Ignimbrite could be one of the triggers for this gap. This gap is very well documented in Crvena stijena, where traces of human presence were significantly reduced after the deposition of Campanian Ignimbrite tephra (Morley, Woodward, 2011; Mihailovic D., Whallon, 2017). In considering this gap, Morley and

Woodward (2011: 690) are taking into account potential environmental crisis associated with this eruption and possibly compounded by climate deterioration caused by Heinrich Event 4. Unfortunately, recent search for tephra and cryptotephra remains in the stratigraphy of Romualdova pecina, Mujina pecina, and Velika pecina in Klicevica did not give positive results (Davies et al., 2015: Tab. 5, a ).

Some other authors also argue about the effects of the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption on the demise of the Neanderthals. Black et al. do not consider this volcanic event to be the only reason for the Neanderthal extinction, but they do not exclude its possible impact on Neanderthal everyday life (Black, Neely, Manga, 2015). Its potential impact on the hominin population and subsistence is also hypothesized by Fitzsimmons et al. (2013).

Future research in the region should focus primarily on finding new sites that would shed light on some of the issues raised above. Of particular significance would be the discovery of well-stratified sites with Late Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic layers. The presence of carinated and nosed end-scrapers in north Dalmatia, which could be of Aurignacian age according on typological grounds, should encourage investigation of the potential Early Upper Paleolithic sites in this area.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Natalija Condic from Archaeological Museum in Zadar for the long and productive collaboration in field research of Velika pecina in Klicevica. We are thankful to the Archaeological Museum in Zadar for the permission to publish artifacts from Radovin-Dracice (Fig. 5) that are part of the Museum’s collection. Our thanks also go to Martina Roncevic for artifact drawings, Robert Marsic for profile drawing, Ivan Condic for Velika pecina in Klicevica plan drawing, and Miroslav Vukovic for the design of Figure 2. Field work in Velika pecina in Klicevica was funded by Croatian Science Foundation (project number HRZZ-09.01/232) and Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia. Field research was also financially supported by Zadar County and Archaeological Museum in Zadar. We would like to thank the Symposium Organizing Committee for the invitation to participate in the conference The Origins of the Upper Paleolithic in Eurasia and the Evolution of the Genus Homo that was held in Denisova Cave, Altai, Russia, July 2–8, 2018. This paper is an extended version of the conference presentation. We thank Buga Novak for English translation.