Личная конкурентоспособность на рынке труда: сущность и классификация составляющих элементов

Автор: Сабетова Т.В.

Журнал: Вестник Воронежского государственного университета инженерных технологий @vestnik-vsuet

Рубрика: Экономика и управление

Статья в выпуске: 3 (69), 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

В статье исследуется явление конкурентоспособности на рынке труда. Отмечается, что данное явление привлекает большое внимание в областях психологии, социологии и педагогики, однако экономические исследования этой проблематики недостаточны, что доказывает актуальность предложенной темы. Конкурентоспособность любого субъекта означает его способность противостоять конкуренции с подобными субъектами в конкретной среде. Это предполагает необходимость исследования конкурентоспособности работника на рынке труда на основании исследования конкуренции. Термин «конкуренция» имеет множество определений, и автор показывает, что наиболее применимым для рынка труда является понимание поведенческого подхода. Автор также считает, что все особенности конкурентоспособности как в целом, так и на рынке труда, следует изучать и рассматривать, учитывая конкретные пары носителя конкурентоспособности и потребителя его продукта или услуги, применительно к рынку труда – трудовой услуги. Кроме того, автор в данной статье соглашается с мнением о том, конкурентоспособность индивида представляет собой совокупность его способностей, компетенций и мотивов, что предполагает возможность того, что элементы, составляющие такую конкурентоспособность могут как проявляться, так и не использоваться на момент исследования либо в течение периода времени любой протяженности. Существенная часть статьи посвящена путям и способам приобретения компетенций. Все сказанное подвигло автора предложить сложную классификацию по множеству оснований характеристик, включаемых в понятие конкурентоспособности работника на целевом сегменте рынка труда. Утверждается, что, несмотря на невозможность составления полного перечня качеств, полезных для той или иной профессиональной деятельности, их классификация по источникам, энергоемкости, длительности формирования, способам и сферам приложения, принадлежности разным подсистемам личности, может с успехом применяться для различных целей исследований и практической деятельности.

Конкуренция, конкурентоспособность, рынок труда, сегменты рынка труда, личность, компетенции, трудовая мотивация

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140229596

IDR: 140229596 | DOI: 10.20914/2310-1202-2016-3-274-282

Текст научной статьи Личная конкурентоспособность на рынке труда: сущность и классификация составляющих элементов

The conceptual apparatus of competitiveness as a scientific knowledge area at the micro, meso and macro levels is not yet fully formed. No universal technique for complex estimation of competitiveness of an organization as a system has been designed. Also there are no methods for individual sectors of the economy, as well as for certain market types, including resource ones.

The phenomenon of competitiveness in the labour market and the attention to it in the scientific

community is not new, as it naturally arises from such an important and socially relevant in the labour market as unemployment and the associated competition for positions. However, as the study of scientific journals proves, the focus of competitiveness and potential wage workers is placed by social scientists and educators, while the economists do so to a small extent only. The formers actively explore personal and professional characteristics of a person, making him competitive employee, paying special attention to young people just at the start of

Вестник ВГУИТ/Proceedings of VSUET, № 3, their career, as well as graduates of various educational institutions, justly believing that considerable part of the features providing competitiveness is formed due to the efforts of those organizations.

However, we should point out, that it is important to consider the competitiveness in the labour market in a way accepted by economics. The labour market remains one of the resource markets, albeit with certain unique features.

According to R. A. Fatkhutdinov, ‘competitiveness of a business unit means its ability to resist rivalry with similar units’ [9]. Competitiveness in an extended sense can be described as a subject’s (whether a company, region, or person) ability to achieve his goals under the condition of competitors’ antagonism. From the point of view of studying companies’ competitiveness, the measure of a subject’s competitiveness is ‘comparison of forces’ between this subject and his main competitors within the market. In the opinion of L. S. Egorova and A. A. Makarychev, ‘company’s competitiveness is its ability to resist rivalry compared to the similar companies in that market’ [5]. We believe it consistent to apply such approach to any subjects of competition. In this case is becomes clear that the term ‘competitiveness’ is closely related to the term ‘competition’ and its specific features associated with particular market, as the same economic subject may act simultaneously in different markets, and with different degree of competitiveness.

It implies the necessity to study employee competitiveness in the labour market in such sequence:

-

1. Study of the term ‘rivalry’ in economics.

-

2. Scrutiny of the labour market specific features as well as of labour itself as an object of market exchanges.

-

3. Consideration of the labour market features from the point of view of rivalry existence and development in it.

-

4. Creation of the definition for the term ‘employee competitiveness in the labour market’ of its reasoning.

-

5. Grounding of the specifics of competitiveness formation within labour market.

-

6. Researches of the matters of assessment, measurement, and deliberate action on the employee competitiveness in the labour market.

According to Definition dictionary of Russian language by S. I. Ozhegov [7], competitiveness can be defined as the ability to stand competition, to resist competitors. Market competition is dynamic and progressing process which consists of the companies’ rivalry for limited effective demand of consumers with the available market segments. The term ‘competition’ has various definitions which can be classified into three theoretical approaches: conductbased, structural, and functional approaches.

The conduct-based approach of this category was the first to arise in the 18th century in the works of Adam Smith and Karl Marx. In the neo-classic variant of the conduct-based approach, supported by P. Heine and M. Porter, the rivalry is presented as struggle for rare economic benefits [12]. Despite the fact that contemporary labour market in most cases is considered as labour spill-over market, we cannot deny that usually the business requires not just any labour effort provided by any person, but very special knowledge and skills possessed by few people. So, the conduct-based approach to understanding the competition is very well applicable to the specific features of the labour market.

Over the 19th and 20th centuries the structural approach spread in economics (C. R. McConnell, S. L. Brue, A. O. Cournot, F. Edgewater, etc.) where the term ‘competition’ defines the market structure and conditions as opposed to the term ‘rivalry’ used by the conduct-based approach for the struggle among the economic subjects at the micro level.

The functional approach describes the role played by the competition in the economy (F. A. von Hayek, J. A. Schumpeter, etc.): start of innovative business, rivalry between the old and the new, modernization and re-engineering. We see this approach as applicable to the labour market to some degree, especially in relation to the segments that most reflect the specifics of the contemporary knowledge economy: innovation sector, competency development, life-long learning, etc.

Most recent approach to classic competition theory was as follows: ‘Competition as economic phenomenon has lost its classic meaning of collision of business interests in attempt to achieve the same objective’. The basis for an organization’s success and development is cooperation and collaboration. Within the labour market this change is even more clearly observed than anywhere else. First of all, it is manifested through labour division and cooperation. No matter how skilled and knowledgeable is a single worker or expert, no matter how great his labour productivity is; there is very limited range of activities where he can implement these qualities, producing certain economy result quite alone. Much more often an alliance of numbers of executives, as well as managers is required for obtaining economic results, any such alliance (work group, company, or national economy with its complex structure) weak link principle is in action which means that the result obtained will be limited to the capacity of the worst member of the alliance, not the best or even average.

The first scientific works concerning competitiveness were published in early 1980s. They may be divided into several groups in accordance with the schools of economics:

-

— American school (M. Porter, C. R. McConnell, S. L. Brue);

-

— Austrian school (I. M. Kirzner, F. Von Hayek);

-

— Russian (G. N. Ruzavin, R. A. Fatkhutdinov).

The most well-known concept among them was the M. Porter’s theory which diffused throughout the world in 1990s. At the same time the matters of regional, good, industry, and national competitiveness were actively researched as well as the related theories like limitless wants theory, price and market theory, extra-market factor influence, etc.

According to many authors, the competitiveness is a multidimensional concept. One may recognize competitiveness of goods, services and technologies, of companies and organizations, branches of industry, region, national economy, specialist, graduate, human resources, etc.

N. V. Vasilenko notes, that all these cases are united by the same feature of ability of the competitiveness bearer (possessor of the competitive advantages) to overwhelm the rival and achieve better results in their struggle for better conditions [3].

In theory and practice of economics competitiveness is one of the key ideas which can be considered as a specific form of manifestation of more general concept of performance along with similar terms of benefit, value, efficiency, etc., varying in terms of generalization degree and interconnections. It is obvious that the only bearer and exponent of any abilities is a human being, living matter.

Goods, service, business, or any other object in itself, unlike living matter, can not possess any ability, including competitiveness. Speaking of the labour market where labour services are exchanged, or sold, we state the same idea – no such service may possess any ‘objective value’. Only a seller and buyer are able to evaluate the degree of an object’s attractiveness, or its competitiveness [3]. Thus, competitiveness, including that of an employee, cannot be studied separately from the specific pair of Employee and Employer (Position).

Work force quality is a total of individual characteristics manifesting through labour and including qualification, personal and professional qualities of an employee. The work force competitiveness is sometimes defined as an aggregate of qualitative and value characteristics of the specific goods – ‘work force’ – that provide satisfying of specific employer’s requirements.

In psychology, competitiveness is interpreted as a basic characteristic of an individual determined by conscious and subconscious mechanisms. In pedagogy, competitiveness is seen as complex characteristic including such parameters as ‘age, somato-mental health, appearance, abilities, intelligence, energy resources as well as moral aspects (personal values, beliefs, personal limitations, etc.). Modern researchers in pedagogy pay greatest attention to the students’ and graduates’ competitiveness, and this matter is closely related to the idea of employee/spe-cialist competitiveness. Specialist’s competitiveness is based on the complex of various abilities (gnostic, projecting, constructive, organizational, communicative) and the development of the skills for these abilities implementation for various and changing situations of some activities or everyday life.

Abilities are something that cannot be reduced to knowledge and skills but provides their speedy grasp, consolidation, and effective practical application. Competitiveness interpreted as one of the abilities may be realized in various activities including those we see as labour, such as sports, research, entrepreneurship, arts, which all may serve as jobs.

So, S. N. Yaroshenko asks whether there are many types of competitiveness instead of the only one, and answers this question in the affirmative. One person may be successful as a machinist, another as a manager, yet another as artist, etc. [11]. We assume, however, that one should not speak of various types of individual competitiveness but of scrutinizing competitiveness with regard of certain situation, and never otherwise. We accept that it is correct to view and assess an employee’s competitiveness not within the labour market in general but within its segments which are available or desirable for an individual. Nevertheless, it remain incorrect to divide the competitiveness into different types in relation to those segments, and one of the proves for this idea is the fact that some factors determining the individual competitiveness remain the same for various labour market segments, while others greatly differ.

According to the statement of E. A. Seregina and V. V. Kot, personal competitiveness is an integral characteristic conveying the individual’s internal attitude to the performed activity and functions. Study of the essence of the competitive individual reveals its close connection with labour and professional activity as only use of certain personal characteristics within the labour market testifies its competitiveness [8]. Personal competitiveness certainly may show itself in any types of activities. However, we agree with the researches mentioned above in two aspects. Firstly, employee’s competitiveness is closely interconnected with personal competitiveness and, in essence, results from the latter. Secondly, despite the rivalry and personal competitiveness manifestations in wide variety of activities such as studies, sports, communications, gaining affection and winning spurs, the only place for economic manifestation of personal competitiveness remains within labour market and working career.

So, we come to the conclusion, that the following can be stated considering the individual competitiveness within the labour market:

-

1. It suggests the individual’s possessing of certain abilities which may be personal or professional.

-

2. Those abilities may be realized or not at the moment of the observation, but they are to

-

3. Just any individual characteristics cannot form his competitiveness, but only those meeting the actual or potential employers’ requirements.

-

4. It follows from the latter, that an individual cannot be absolutely competitive within the labour market as a whole, his competitiveness existing only for some market segments.

-

5. Employee’s competitiveness in the labour market is the special case and the only economic manifestation of personal competitiveness.

-

6. It is possible to assess personal competitiveness only by comparison with other persons, while absolute value of competitiveness cannot exist.

be accompanied by the internal personal ability of their implementation under certain conditions.

The most complex but practically important question is which characteristics form the individual competitiveness in the labour market, and how an individual can obtain those characteristics.

We have already marked, that those shall be personal and professional qualities useful for professional function performance, the degree of such usefulness being defined by the labour consumer (employer). Due to labour market heterogeneity and fundamental differences of the requirements set for applicants for various vacancies it becomes obvious that some general list of characteristics of an absolutely competitive individual cannot exist even in theory. Nevertheless, it is possible, firstly, to point out that various features differently affect the individual competitiveness under various conditions and within different labour market segments. Secondly, we need to stress out that all such features form a considerable sub-system within an employee’s personality, and thus all the system theory principles are applicable to it, including interaction and inter-influence of all elements, synergy and emergence, and all attributes of open systems. Thirdly, despite the impossibility of making the complete list of qualities useful for some professional activity, the classification of the elements forming labour competitiveness is possible and desirable. The classification foundations vary greatly including sources, effort input, and period of formation; methods and areas of application; inclusion in the various personality sub-systems.

The latter foundation produces widely different classification groups depending on which theory of personality structure forms its basis. In our opinion, theories like those of S. Freud, C. Jung, E. Berne are hardly suitable for research of the features forming personal competitiveness in general and within the labour market in particular. The theories much more suitable for such purpose were created by K. K. Platonov and S. L. Rubinshtein which are actually similar to some degree. We used the latter as the basis for classification finding it the most simple and easy to interpret.

Its basis provides the opportunity to link three elements of the personality structure found by S. L. Rubinshtein with the groups of features determining the personal competitiveness within the labour market (table 1).

If we apply competency approach to the described classification, then the second and third sub-systems include the set of personal professional and social competencies from the labour market competitiveness point of view, while the first one contains the motivation for its expanding and improving.

Table 1

S. L. Rubinshtein’s personality structure units and their links to employee’s competitiveness elements

|

Sub-system |

Units |

Competitiveness elements |

|

orientation |

needs, interests, ethos, beliefs, motives |

targets, career aspirations, labour and development motivation |

|

knowledge and skills |

knowledge and skills, but also habits, experience, etc. |

the total of all features gained during the lifetime including two groups: professional and personal |

|

personal features |

temper, character, abilities |

inborn features, abilities and disposition as well as features and skills gained without effort |

A. A. Fedchenko and K. A. Danker [10] suggested to define the elements of personal competitiveness based on their physical properties, such as health, including physical, mental and emotional conditions; emotional intelligence, including, among other issues, adaptability for the needs of the labour service; and professional knowledge and skills gained from education and applicable for any or particular professional activity. The authors united the second and third blocks into a complex of inborn and gained competencies without dividing them into these two groups.

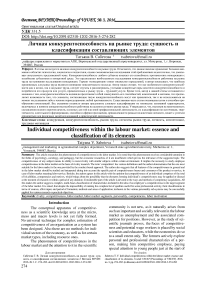

Meanwhile we deem it desirable and important for any practical recommendations to classify the competencies based specifically on the ways of their attainment (figure1).

Figure 1. Competitiveness elements in terms of the methods of their attainment

We interpret deliberate formation or development of competencies as self-contained activity type with independent time and effort exertion. Such activities include but are not limited to training, both on-job and off-job. An individual may attain competencies by means of self-education during his leisure time. In the course of his work an employee may try and apply or even invent new methods of operations taking into account his or other workers’ experience, exerting his creativity, and often spending additional time and effort for that or temporarily reducing his labour productivity. All those examples should be viewed as special efforts for gaining come competencies and achieving professional improvement, though it is often difficult or even impossible to differentiate ‘natural’ and ‘deliberate’ competency acquisition.

It is also important to point out ultimate necessity of time and effort for acquisition of the vast majority of competencies required for any job performance.

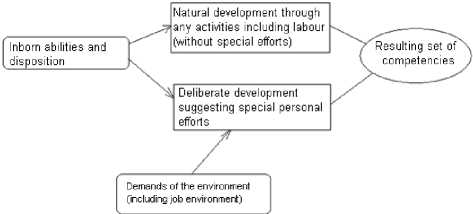

No less important is competitiveness element classification based on the period of their acquisition within human lifetime, or prevailing in some periods. Analysing the moment of competency acquisition one should take into account that personal psychological group is formed during one period of life (mainly during the childhood and youth), while professional group (knowledge and skills) is gained later (figure 2).

In the end we reach the conclusion, that the ways of work competency acquisition also vary depending on the individual’s age, occupation and the specific features of the competency in question (figure 3).

It is essential, that under such interpretation of the work competency acquisition stages we get to understand some of the features of this process.

Firstly, despite the division of the studied competitiveness elements into professional and others, including physical, psychological, and social, this division is virtual only and it is almost impossible to make it in actual situations.

------ - psyclioemotional competencies

------- - education and pi ofessional skills

Figure 2. Competitiveness elements in terms of periods of their development

-

- forma! additional education (second degree, advanced training, etc.)

-

- additional within-post training

-

- experience gained from the work itseif

-

- self-education and

se!f-improvement

- forma! basic education

- first working experience

-

- forma! schoo! education - additiona! out-of-schooi education

-

- deveiopment of abilities within family

t/?e/r further life-long development

-inborn abilities and dissposition

Life

Figure 3. The ways of forming labour competencies at the various stages of a person’s life

Secondly, even though an individual enters his working career with a set of competencies formed and sufficient for rivalry within the labour market, competency development in the course of work in particular has a lot more sufficient effect on personal competitiveness, as during this period an individual seizes the opportunities to gain the competencies exactly as required by the given employer or by the labour market segment. Thus, he may choose not waste his time and effort for developing unnecessary/optional knowledge and skills. Many researches in the field of work/profes-sional competency acquisition are dedicated to finding ways of professional training improvement towards its suitability for the employers’ needs [5]. However, further on-job competency acquisition imbibes such selection of characteristics almost

Вестник ВГУИТ/Proceedings of VSUET, № 3, without any effort both on the part of special organizations and the executives themselves.

Thirdly, the life-long learning concept under such conditions instead of being new and artificially inculcated becomes natural and unavoidable. Obviously, the intensity of an individual’s competency development after the start of his working career may vary greatly depending on the economic demands, personal disposition, and situational factors. Nevertheless, this process cannot cease till the end of economic activity of the individual but may only need some correction concerning improvement points, intensity, and steadiness. At the same time we should not disregard the methods of competency acquisition typical for this period of life, especially the ones we termed as deliberate, including core and additional education and self-education and other forms of personal and professional growth. Such competency acquisition ways are of even greater importance concerning the excessive competencies which are not currently applied by an individual for his work. The need for such competency acquisition occurs in the situations:

-

— an employee moves to another company, industry, or profession;

-

— job description changes abruptly within the same occupation due to the need of business adaptation to external changes;

-

— increase in employee’s duties (for instance, internal secondary employment).

Besides the time and effort exerted for gaining the characteristics making an individual competitive in the labour market, one of the significant bases for classification is the ways, situations, and intensity of their actual application.

We have already noted, that an employee’s competitiveness can only be determined as how well his characteristics meet the employer’s requirements, as each occupation is to a certain degree unique and the optimal set of competencies is equally distinct. Such optimum may be outlined in theory but remains practically inaccessible. Still, the set of competencies actually possessed by the employee winning the rivalry for a given job differs as well, depending on the job, company, and immediate situation. It should be mentioned, that the same characteristics will be indispensible for one case, for in the other, immaterial for the third one, and inapplicable for the fourth. This naturally complicates the task for the researcher wishing to classify those characteristics. Thus, we suggest, that the actual content of each classification group defined based on the ways of use may vary greatly. However, this does not make the classification itself irrelevant.

Many researchers, such as A. A. Borisova [1], P. M. Kozyreva [6] note, that achievement of goods results in different activities, including studies and further work within the studied major, often require different sets of qualities, abilities, efforts, and competencies. Moreover, enquiries undertaken among Moscow students by M. B. Bulanova and P. A. Borisova prove, that the very same students do not equate successful education and future successful employment and professional integration [2].

The same can be stated concerning the competencies required for job hunting and acquisition and those necessary for successful work in the chosen position. For example, M. V. Volodina studied the new graduate market segment and found unreasonable complexity of the job hunting process itself, the complications often being implied by the applicant himself because of his unrealistic ideas and wrong interpretation of external information [4]. For instance, particular attention is paid to clothing, confident behaviour, demonstrating the loyalty to the employer, as well as the attempts to guess the expected answer instead of giving the sincere one, etc. It is most unlikely, that any of these abilities can help an accountant or programmer in their work.

Besides, the employers also seek different characteristics in different groups of applicants in terms of age, gender, social status, and profession. They also evaluate internal and external applicants by different parameters.

Thus, we define the following groups of personal work competencies in terms of the period of their application:

-

1. Competencies applied for initial creation of the target competency set by means of education, self-improvement, gaining experience, etc., which may be termed ‘learning, or development competencies’. Even though they cannot affect the immediate work performance we believe in future the employers will pay more and more attention to these competencies, as they well suit the life-long learning concept and the conditions of knowledge economy.

-

2. Competencies applied for job search and application, which can be called ‘direct rivalry competencies’. They include unbiased assessment of a person’s achievements as well as his actual career aspirations; self-presentation; communications, etc. We may note, that despite the objective need for such competencies, an employer may not always view their advanced development as an advantage in an applicant, as it probably results from frequent practice during extended unemployment periods.

-

3. Competencies useful for effective operation under pressure, crisis, or new and unexpected conditions, whether at work or in private life. They might be named ‘adaptation competencies’ and viewed more as social than professional skills. Still, employers sometimes check them in the applicants even where the vacation does not directly involves dealing with stress and emergency.

-

4. Competencies directly applied for effective job performance, or ‘professional competencies’.

An individual at any moment of observation is in possession of a certain complex of abilities, knowledge, work and social skills, etc. Within a period of any considerable duration he adds to this complex by means of gaining new or improving present characteristics. Earlier we mentioned that an employee competes with his rivals using both professional and other competencies. However, only some part of the total of individual’s skills and qualities do and can improve his competitiveness in the labour market. At each particular moment and position he normally applies but few of these skills and qualities. The longer the observation duration is, the larger and more heterogeneous part of individual’s potential is used. However, there is great probability, that some of the elements of his potential remain disused during considerable periods or even throughout his life. However negligible is this disused share we believe that it should not be ignored from the point of view of time and effort consumption.

As the result we think it possible to suggest the individual potential elements based on the intensity of their application:

-

— regularly/constantly used elements, which form the basis of the professional activity of a person;

-

— periodically/sporadically used elements required for casual work, search of new position, in crisis situations, etc.;

-

— optional elements used for routine operation but unnecessary for it and applied at the employee’s decision; they may improve his performance, or make his work easier, or just form his habits;

-

— latent elements disused during long periods; however, they might be useful or even important in case of dramatic changes in situation, whatever is the probability of such changes.

One may also argue that some elements should be termed ‘dead’ where the probability of the situation when an individual needs them tends to vanish. However, the length of the work life, high volatility of the labour market and of economy in general, make any estimation of probabilities as close to zero imprecise and risky. That is why we assume it systematically right to consider all long disused competencies as ‘latent’, even if they will never be needed during a given person’s life. The choice of action when an individual faces the opportunity to acquire a competency tending to become latent resides in that same individual and his subjective assessment of probabilities.

The way of application of the individual’s characteristics forming his competitiveness in the labour market can also be of considerable importance. Such methods presumably include intuitive, conscious, and reflexive.

The characteristics not recognized by their bearer in their fullest extent, or those of which presence the latter is totally ignorant, or never used before, are applied intuitively, sub-consciously. The key feature of such characteristics is that the bearer cannot consciously predict the results of their application.

The individual applies the characteristics and competencies consciously, if those competencies are well developed for adequate use; if the individual knows how to use them and what results to expect according to his logic and experiential estimations.

The individual applies the characteristics and competencies reflexively when the latter are developed to the degree of automaticity by means of regular use. However, they might prove unsuccessful because of the differences between the new situation in question and the usual situations where the competencies had been forming and improving.

The last important feature for labour market participant’s competency classification is the degree of their development, of their acquisition. Pedagogy defines three such degrees: knowledge, skill, proficiency.

Knowledge is the precondition for activity but may never result in capability of performance. Existence of such capability conditioned by knowledge and manifested in practical action is termed skill. Skill may be developed and manifested to various degrees of perfection. It is normally controlled by bearer’s consciousness but at the same time he can never realise the whole complex of his performance elements. Some procedures and operations within it become automatic through numerous repetitions and are executed without conscious control, thus turning into proficiency.

Conclusion

Proceeding from this estimation position we can suggest dividing all social and professional competencies of a person into the following groups:

-

1. Sufficient: the competency is present and developed enough for satisfactory performance. But it may require further improvement in some cases, for instance, career progress.

-

2. Superfluous: the competency is present and developed up to the degree quite unnecessary for the position in question, allowing gaining bet-ter/higher post. However, this does not happen for some reason, like applicant’s ignorance of the requirements, or lack of some other competencies (competency disproportion). Which even is the actual reason, such situation may cause further individual’s dissatisfaction, incorrect self-esteem, decline in the work motivation.

-

3. Deficient: the competency is present but its development is below the desirable level.

-

4. Developing/forming: the competency is being acquired by the individual at the moment by means of training, self-education, or gaining experience.

Список литературы Личная конкурентоспособность на рынке труда: сущность и классификация составляющих элементов

- Борисова А.А. Предпосылки и ограничения формирования конкурентоспособности выпускников вузов//Проблемы современной экономики. 2015. № 2. С. 351-353.

- Буланова М.Б., Борисова П.А. Высшее образование и трудоустройств: современные риски//Вестник РГГУ. Серия: Философия. Социология. Искусствоведение. 2014. № 4 (126). С. 233-240.

- Василенко Н.В. Институциональная конкурентоспособность или конкурентоспособность институтов: постановка проблемы//Научные труды Донецкого национального технического университета. Серия: экономическая. 2011. № 1 (40). С. 187-191.

- Володина М.В. Риск в процессе трудоустройства: формы взаимодействия и тактические приемы//Молодой ученый. 2014. № 19. С. 459-461.

- Егорова Л.С., Макарычев А.А. Управление конкурентоспособностью предприятия//Вестник Нижегородского университета им. Н.И. Лобачевского. 2008. № 6. С. 316-322.

- Козырева П.М. Образование и трудоустройство: возможности и реальность//Россия реформирующаяся. 2015. № 13. С. 304-323.

- Ожегов С.И., Шведова Н.Ю., Скворцов Л.И. Толковый словарь русского языка. М.: Оникс, 2010. 736 с.

- Серегина Е.А., Кот В.В. Теоретические аспекты формирования конкурентоспособности выпускника вуза в контексте характеристик конкурентоспособности работника. В книге «Институциональный механизм преодоления рецессии»: коллективная монография. Ростов-на-Дону, 2015. С. 56-65.

- Фатхутдинов Р.А. Уровни и объекты конкурентоспособности//Современная конкуренция. 2009. № 4 (16). С. 135.

- Федченко А.А., К.А. Данкер Компетентностный подход при оценке уровня конкурентоспособности персонала//Нормирование и оплата труда в промышленности. 2015. № 10. С. 34-40.

- Ярошенко С.Н. Учебно-профессиональная конкурентоспособность студентов вуза как вид личной конкурентоспособности//Известия высших учебных заведений. Уральский регион. 2013. № 5. С. 119-122.

- Kilduff G. et al. Whatever it takes to win: Rivalry increases unethical behavior//Academy of Management Journal. 2015. P. amj. 2014.0545.

- Krugman P.R. Making sense of the competitiveness debate//Oxford review of economic policy. 1996. V. 12. №. 3. P. 17-25.

- Neumark D., Wascher W. The effects of minimum wages on employment//FRBSF Economic Letter. 2015. V. 2015. P. 37.

- Porter M. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: The Free Press, 1985. 592 p.