Literacy and numeracy skills of the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts in the 17th and 18th centuries

Автор: Tataurova L.V., Tataurov S.F., Tataurov F.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Literacy, archaeology, written sources, Russians, reconstructions

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146807

IDR: 145146807 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.4.120-128

Текст статьи Literacy and numeracy skills of the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts in the 17th and 18th centuries

First Russian towns in Siberia were founded as military and administrative centers of the Russian State for defending the newly acquired lands and bringing under control the indigenous population. This mission would have been impossible without economic and civilizational progress. For successful achievement of these objectives, two governors were appointed to towns in the 17th century: one was responsible for military functions, and another for economic issues. Such administrative system also appeared in the decree on founding of Tara (Miller, 1999: 347–353): “And as Prince Andrew leaves Tobolsk… and comes to the new place, and builds and strengthens the town, then truthfully write about that to the sovereign. And let him draw town places, and town itself, and fort on the map, and write down all fortifications… so the sovereign

knows about everything…” (Ibid.: 348). Tax control was also arranged: “And all volosts should take their tribute books in Tobolsk from the Governor Prince Fedor Lobanov—how much tribute was taken from them to Tobolsk… And whatever kind of tribute each would send to the sovereign <…>, he should send the report to Tobolsk to Prince Fyodor. And all kinds of tribute should be personally recorded in the books separately according to kinds” (Ibid.: 350). A special person was nominated to check the fulfillment of orders: “And the Governor Prince Andrew should take with him clerk Kryank Ivanov, who was sent with him from Moscow, to the new town for keeping records. And order him to be the clerk at the sovereign’s office for all cases, and to record all sorts of sovereign’s affairs” (Ibid.).

As a military town, Tara ensured stability on the southern borders of Western Siberia for two centuries. The town, as well as villages around it, were inhabited by the servicemen. In the 17th century, about 80 % of the servicemen of the Tara garrison participated in “distant assignments”. They delivered the “tribute treasury” or documents of local offices to Moscow and accompanied delegations at negotiations with leaders of the Kalmyks and Dzungar people, which required knowledge of foreign languages (Tara v XVI–XIX vekakh…, 2014: 98–99). Soldiers, Cossacks, commanders, and Boyar scions received state salary for their service. Information about it was recorded in salary books and “records of sovereign’s salary to the servicemen”.

Location in the Irtysh valley, with the trade routes going from Central Asia to the north, up to the lower reaches of the Ob River, fostered the destiny of Tara as a trade center.

Tara needed educated people for performing its military, political, and economic functions; skills of literacy and numeracy were acquired by representatives of both urban and rural population of the Tarsky Uyezd.

Making no question of the importance of the written sources in studying the topic, we should analyze the relevant archaeological evidence of the 17th– 18th centuries.

This study intends to establish the level of literacy among the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts in the 17th–18th centuries, using a comprehensive analysis of archaeological, written, and historical sources.

Literacy markers among the urban population of Western Siberia in the 17th–18th centuries

It is challenging and time-consuming to study the spiritual culture of the population in various historical periods from the archaeological point of view. Interpretation of an archaeological source of the Modern Age is based both on the available excavated finds and historical information contained in written, ethnographic, and other sources (Tataurova, 2021).

The issues of literacy among the Russian population of Siberia were rarely studied using archaeological sources; the research is mostly limited to the evidence from Mangazeya. The described finds from the excavated households show that the town dwellers were literate, since they carried out trade business, and their children also studied reading and writing (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2013: 16). Finds evidencing the knowledge of the alphabet and writing skills include wooden boards with the alphabet, dishware, containers, such as barrels, barrel staves, and bottoms, labels of goods, birch-bark fragment with the inscribed beginning of a petition to the tsar, parts of leather goods with letters, words, and texts (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: 129, 130, 291–294; 2013: 16, 24; 2017: 94–95, 99, 114, 115, 120, etc.), as well as thin wooden board with carved text of a promissory note (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: 118).

A collection of items indicating numeracy skills includes counting sticks, labels on goods (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: 129, 130, 291–294; 2017: 94– 95, 99, 114, 115, 120, etc.); writing accessories, such as bronze (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2013: 16, 24) and ceramic (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2013: 16; 2017: 135– 136) inkpots, as well as details of a wooden wax tablet for writing (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: 118).

Pens and cases for keeping them have also been found (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2013: 16, 24; 2017: 143). Noteworthy is a writing pen made of goose feather with paintbrush made of squirrel tail hair at the upper end (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2017: 143). Such paintbrush could have been used for writing in gold and silver or coloring miniatures and initials (Gudkov, 2014: 23).

In the 16th–17th centuries, Tobolsk residents used clay inkpots varying in shapes and designs (Balyunov, 2014: 52).

According to oral report of the excavations’ head O.M. Anoshko, the cultural layer of the town (the First Gostiny excavation area near the Indoor Market, Bazar excavation area, trading quarter) contained counting sticks and glass inkpots. A metal pen with gold plating from the layer of a household of the late 17th to the first third of the 18th centuries was found in the excavation area at the trading quarter (dated by the coins of Peter I period)*.

The range of goods at the Tobolsk market of the 17th century shows the needs and demand for stationery and other items indicating literacy of the population. First of all, it included paper, which was imported to Tobolsk throughout the entire 17th century (see Table ). The amount of paper was measured in stacks. A stack included

Stationery and other items from the range of goods for literate people at the Tobolsk market of the 17th century

|

Year of arrival of goods |

Copper inkpots, pcs./rubles |

Nut galls, pound/rubles |

Paper, stack/rubles |

Books, pcs./rubles |

|

1639/1640 |

31/11.8 |

80/16 |

58.9/58.9 |

173/46 |

|

1655/1656 |

– |

150/30 |

119/119 |

– |

|

1668/1669 |

– |

80/16 |

124/124 |

– |

|

1686/1687 |

– |

– |

208/208 |

1/6.5 |

|

1694/1695 |

– |

10/0.9 |

70/70 |

– |

Compiled after: (Vilkov, 1967: 91, 95, 110).

24 dests (sheafs); dest included 24 sheets (Belovinsky, 2007: 168; Stolyarova, Kashtanov, 2010: 116). Thus, one stack consisted of 576 sheets of paper, most likely of the dest format (full sheet measuring 50 × 70 or 30 × 50 cm). Each of them was subsequently cut into three parts along the longer side, depending on the document size (Gogolev, (s.a.)).

According to customs books, paper occupied the seventh place in the structure of goods brought to the Tobolsk market; but by the late 17th century, its supply declined despite of the increasing demand. According to O.N. Vilkov, this decrease in import resulted from the establishment of domestic paper production (1967: 120). However, paper production in Tobolsk emerged only in the mid-18th century. In 1745, a paper factory was created 15 versts from the town, for manufacturing writing and wrapping paper (Zapiski…, 1824: 399).

In addition to paper, the range of goods needed by literate people included writing utensils (inkpots), raw materials for preparing an aqueous solution used for writing (nut galls), and books imported in the second and last quarter of the 17th century (Vilkov, 1967: 91, 95, 110), as well as glasses that entered the market in 1668/69 in the amount of 108 items, with a total value of 6.1 rubles (Ibid.: 108).

The fact that the residents of Tomsk governor’s estate knew how to write is confirmed by such finds as clay inkpots. M.P. Chernaya points to signet rings intended for sealing papers and goods as items related to office administration (2015: 192, 193).

Literacy among the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts

The document analysis identified the differences in education level among the population of Tara and its rural periphery in the 17th–18th centuries. There were illiterate persons, such as “Andreev Grigory—a Tara soldier, illiterate. In 1652, he had no ‘trade or production’, D. Matveev would sign for him [while receiving salaries – the Authors ]” (Sluzhiliye lyudi

Sibiri…, 2019: 26). However, there were also educated people, for example, the one who signed for G. Andreev while receiving his salary—“Matveev Danila—a Tara mounted Cossack of the reiter hundred military unit, literate <…> On September 16, 1660, he brought a letter from Moscow; on December 29, 1665, under the orders of commanders of a ten soldiers units A. Dobrynin and O. Bogdanov, he was sent with the sable treasury to Moscow” (Ibid.: 553).

Analysis of written sources has revealed that 87 persons were literate among the 2580 servicemen and other officials who lived in Tara in the 17th–early 18th centuries*, that is 3.4 %. These were servicemen of various ranks who lived in Tara, including the Boyar scions such as Pavel Kosteletsky**, who spoke the Tatar language and, in addition to his service, performed the duties of a clerk (Krikh, 2016: 20, 21; Sluzhiliye lyudi Sibiri…, 2019: 453). His son Semen, promoted to the class of Boyar scions in 1645 (Krikh, 2016: 250, app. 3), was literate; he signed for other persons while receiving salaries (see, e.g., (Sluzhiliye lyudi Sibiri…, 2019: 61, 302)). The servicemen included the clerks of the government office and indoor market Alexey Ivanov, Petr Kolpev, Ivan Konakov, Boris Nevorotov, Mikhailo Ivanov Ostrovsky, and others (Ibid.: 339, 431, 435, 613), as well as governor deputy and Cossack commander Fedor Elagin and Nazar Zhadobsky (Zhadobskoy, Zhedobsky, Zhedovsky) (Ibid.: 282, 301), Cossack and army commanders of a hundred soldiers’ units I. Vatov and Nefedya Matveev (Ibid.: 154, 554), commander of a fifty soldiers’ unit Oska Kuznetsov, commander of a ten soldiers’ unit Andrey Varfolomeev, cavalry captain Voin Volkonovsky (Ibid.: 143, 176, 480), reiters Alexei (Oleshka) Ivanov, Duma Krishtopov (Ibid.: 338, 464), mounted Cossacks Aleksey Goisky, Aleksey Ivanov, Ivan Nefediev, and cannoneer Andrey Rezin (Ibid.: 213, 338, 624, 750).

Literate were church officials, who were invited by the servicemen to sign for them after receiving money. They included Fr. Savva (Sava)—the “spiritual father, priest” of St. Nicholas Church (Ibid.: 108, 491, 568, 570, etc.). Savva Antipin lived in the fortified part of the town; in the late 17th century, his household passed to his grandson, mounted Cossack Petr Popov (Ibid.: 715). The following priests were mentioned: priest Anton (Ibid.: 130, 615), reader of St. Paraskeva Pyatnitsa church ( pyatnitsky dyachok ) Fr. Goiskov (Ibid.: 128, 556, 754). Icon-painter O. Nefedov also signed for the servicemen (Ibid.: 128). Notably, by the mid-18th century, there were four icon-painters in Tara (Tara v XVI–XIX vekakh…, 2014: 126).

It is known from written sources that in the late 16th century, immediately after construction of the town was completed, it was ordered to bring “2 stacks of writing paper… Books, Hexameron, and Psalter with the selected psalms” (Tsvetkova, 1994: 8), along with necessary supplies and ammunition from Moscow.

In the 17th century, paper for writing would come to the Tara market mainly from Tobolsk (Krikh, 2016: 42; Tara v XVI–XIX vekakh…, 2014: 106). In the 17th to the first half of the 18th century, ink and materials for its manufacturing were imported along with paper, since only in the early 1760s A. Bekishev designed “vitriol ink”. He boiled up to 50 puds of ink a year and sold it for 2 rubles per pud, but this production lasted for no more than five years (Tara v XVI–XIX vekakh…, 2014: 122).

In addition to paper, birch-bark might have been used for writing texts and religious books both in the State Orthodox and Old Believer traditions (Gudkov, 2014: 29), but so far no birch-bark documents have been found in Tara.

The “documentary” evidence mentions counting sticks (Fig. 1, 1 ), trade seals, and wooden trade label with the inscription “hops” (Tataurov S.F., 2017). According to written sources, in the 17th century, servicemen of various ranks were actively engaged in the sale of hops “of their own production”. For example, the commander of the fifty soldiers’ unit Ivan Timofeev Nedopeka sold half a pud of hops in 1637. On December 18, 1647, he “brought for sale” 2 puds of hops for 6 rubles. On February 20, 1648, mounted Cossack Grigory Sumyanin brought for sale 10 puds of hops. On March 10, 1687, the Cossack son Petr Filimonov brought 10 puds of hops of his own production to Tobolsk (Sluzhilye lyudi Sibiri…, 2019: 614, 823, 917).

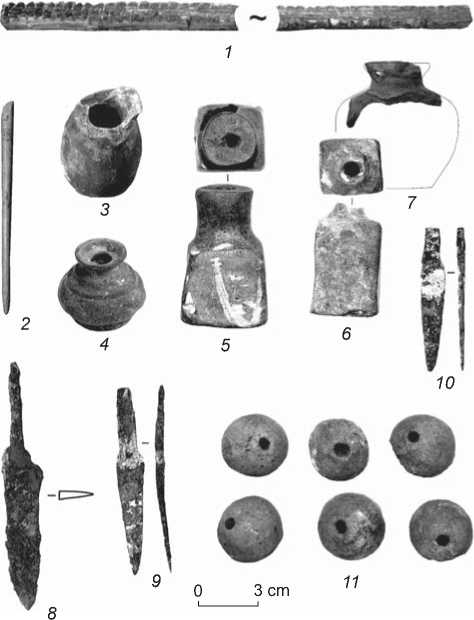

Fig. 1 . Archaeological finds from the town of Tara ( 1–4 , 8 ) and the village of Ananyino, Tarsky District, Omsk Region ( 5–7 , 9–11 ).

1 – counting stick; 2 – stylus; 3–7 – inkpots; 8–10 – penknives; 11 – beads from abacus. 1 – wood; 2 – bone; 3 , 4–7 , 11 – ceramics; 4 , 8–10 – iron.

Most of the servicemen of Tara and its rural districts participated in trading “goods from Russia” and selling livestock, hunting products, fish, butter, “huts with courtyard”, etc. The Tara trade flourished in second half of the 18th century, when a tea route ran through the town (Tataurov S.F., 2017).

Wax tablets were known to be used in teaching literacy in Mangazeya and Tara. These items have not been found, but a bone stylus ( pisalo , lit. ‘writing tool’), decorated with two lines of netlike ornamentation, was discovered in the cultural layer of Tara Fortress (Fig. 1, 2 ). Styluses were also used for writing on birch-bark (Gudkov, 2014: 22).

Stationery from the cultural layer of Tara included inkpots made of clay and metal (Fig. 1, 3 , 4 ); the latter item was similar to the Mangazeya find (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2013: 24). The inkpot from Tara was dated to the 18th century (Tataurov S.F., Fedotova, 2018: 30), but since it was similar to the Mangazeya inkpot, it could have probably been used at an earlier time.

Goose quills, which were sharpened with penknives (Fig. 1, 8 ), were apparently used for writing. These knives differed from similar tools by the small size of their blades

(Slovar…, 1980: Iss. 7, 165; 1988: Iss. 14, 309). Precisely such penknives have been found in the cultural layer of the village of Ananyino, located near the lake of the same name, on the right bank of the Irtysh River, 10 km southeast of Tara. Their total length was 9.5 and 7.0 cm; blade length was 6.5 and 5.3 cm; blade width was 1 cm (Fig. 1, 9 , 10 ). The knives were made using the technique of welding a steel blade onto a soft iron base, and were subjected to soft hardening (Zinyakov, 2017: 428). A penknife from Tara was somewhat larger. Its total length was 12.6 cm; blade length was 8 cm; blade width was 1.8 cm. Such knives were found both in the area of the fortress in one of administrative buildings of the second half of the 17th to the first half of the 18th centuries, and in a building of the first third of the 17th century on the territory of the fort.

The written sources have no information on literacy among the dwellers of Ananyino. The village of Ananyina (Ananyino) was mentioned for the first time in historical documents in the “Book of Records of the Tarsky Uyezd” for the year of 1623/24. In the 17th–18th centuries, several family clans—the Moseevs, Neupokoevs, Skuratovs, and Popovs (Tataurova, Krikh, 2015: 479–483)—lived in the village. The encyclopedia “Servicemen of Siberia” has very brief information about these people: “I. Popov was a Tara soldier. In 1701, he lived in the village of Ananyina up the Irtysh with Moseev, Neupokoev, and Skuratov” (2019: 712). However, they all came from Tara, which means that there must have been some literate persons among them. For example, Stepan Afanasiev Skuratov,

a commander of the fifty Cossacks’ infantry unit, and since 1634 a chieftain, in 1638 sent a petition to receive a grassland near the village of Ananyino, which was satisfied (Krikh, 2016: 73).

Owing to the specific features of the cultural layer in Ananyino, preservation of organic materials was quite poor: only clay inkpots (Fig. 1, 5–7 ) and penknives have been found therein. Ornithological collections at the site are indicative of domestic geese breeding and wild geese hunting (Tataurova, Nekrasov, 2021: 77), and suggest that feathers of these birds might have been used for writing.

Signet rings of noblemen, which were found in Tara (3 spec.) and Ananyino (1 spec.), were associated with literacy and office administration. The shields of two Tara bronze rings were inlaid with colored glass. One ring depicts Latin letters and an inverted shield (Fig. 2, 1 ); another ring shows a shield with a rider on top (Fig. 2, 2 ). A crown with four leaves and four teeth with pearls on the hoop (Fig. 2, 3 , 4 ) appears on the halves of silver rings from Tara and Ananyino. In the 17th century, such image was typical of Russia and Northern German lands (Chernaya, 2015: 205). Signet rings were used for facsimiles; they were a symbol of power and attribute of the social class (Tataurov F.S., 2020).

A ring, inkpot (see Fig. 1, 5 ), set of clay balls (see Fig. 1, 11 ), which we interpreted as parts of abacus, as well as a set of “high status” items (iron two-pronged fork, counting token with inscription “Corneliusa Lauffera”) and other artifacts found in Ananyino, belonged to the same residential complex where a military commander with writing and numeracy skills might have lived (Tataurova, 2018). According to the inventory and results of dendrochronological analysis, the dwelling can be dated to the second half of the 17th century, and according to the coins, to the early–mid-18th century (Tataurova, Sopova, 2021).

A set of 14 clay balls flattened on one side, 3.0–3.5 cm in diameter, with a hole in the middle (0.5 cm in diameter), which were found in the dwelling mentioned above, will be discussed in more details. These balls differed in shape and weight from spindle whorls; they were too small and light to be fishing sinkers, and they have not occurred in the cultural layer of the site before (the area of the excavation was 2500 m2). These items can be identified as “beads” of abacuses, although they were somewhat larger than usual beads.

Fig. 2 . Archaeological finds from the town of Tara ( 1–3 , 6 ) and the village of Ananyino, Tarsky District, Omsk Region ( 4 , 5 ).

1 , 2 – rings with inserts; 3 , 4 – rings with “crowns”; 5 – candlestick; 6 – case for letters. 1 , 2 – bronze, glass inserts; 3 , 4 – silver; 5 – ceramics; 6 – bone.

Peter van Haven, a Danish mathematics enthusiast and professor of theology, who had lived in Russia for three years, wrote in his book published in 1747: “…all Russians, down to the poorest peasants, are very skilled in the counting art. They use a counting board for this <…> it is so commonly used that it can be even found with all kinds of pocket mirrors, writing boards, or calendars attached to it” (cited after (Spassky, 1952: 360)).

Board abacus (Ibid.: 305; Simonov, 2010: 136) was the forerunner of Russian abacus, which has been used by many of our contemporaries until recently. The abacus was a quadrangular wooden frame with transverse bars/ cords, strung with beads. The description of P. van Haven mentions that “beads can be made of horn, ivory, glass, wood, metal, or of peas, etc.” (cited after (Spassky, 1952: 363)). Abacus beads could have also been made of ceramics. During the excavations of a pottery workshop of the 17th century in Moscow in 1946–1947, “a collection of clay rings was discovered. Their outer diameter is 1.9–2.2 cm; inner diameter is 0.6–0.7 cm; thickness is 0.5– 0.6 cm. In shape, these rings resemble whorls; they were much smaller than clay whorls. The rings are most similar to beads used in our time in abacuses. Some rings, made of light clay and well baked, do not have glaze, but most of them are covered with green or yellow glaze” (Rabinovich, 1949: 28). According to M.G. Rabinovich, these items were intended for manufacturing board abacuses, which at that time were in great need in numerous offices of Moscow (Ibid.). The Moscow finds differ from the abacus “beads” from Ananyino in size and presence of glazing.

In Siberia, board abacuses were known and were in demand in the taxation system related to agriculture (allocation and control of arable land, hayfields, and other lands). They might have been used in 1689 by Boris Nevorotov, the Tara clerk of the government office, when together with Y. Cheredov and V. Kulichkin he conducted a census of lands owned by the servicemen, which were sold to the Siberian Bukharans (Sluzhiliye lyudi Sibiri…, 2019: 613).

A board abacus that M.A. Zeiger dated back to the 17th century (Lokhnesskoye chudo…, (s.a.)) is kept in the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve. In our opinion, the collection of clay balls from Ananyino can be considered to be a part of a similar device for counting, which was made by village craftsmen. The sizes of such board abacuses most likely depended on the circumstances of their use.

The need to write letters, petitions, and other documents required “workstations” for scribes, and provision of acceptable lighting. Insufficient lighting affected vision, which may probably explain the arrival of a large batch of glasses to the Tobolsk market in 1668/69 (Vilkov, 1967: 108).

Lighting residential, administrative, and church premises of Tara and its rural periphery have already been discussed (Tataurov S.F., 2019; Tataurova, 2017). The main illumination tools were rushlight holders of various types. However, candle lighting was more convenient, especially in administrative offices. This is confirmed by pictorial sources, such as illustrations of the Gospels of 1681 (Evangeliye, 1681) and Psalter of 1636 (Psaltyr, 1636), as well as paintings (Chernaya, 2015: 190). Metal candlesticks and tweezers for removing soot have been found in Tara. Candles were used in everyday life mainly by governors and their entourage (Tataurov S.F., 2019: 41–42). In the late 16th century, wax was brought to Tara from Moscow: “2 buckets of church wine, 2 puds of wax, 4 pounds of incense, 5 pounds of thyme” (Tsvetkova, 1994: 8). In the 18th century, wax was not mentioned among the imported goods; only ready-made candles—colored and ornately shaped—were indicated (Tataurov S.F., 2019: 42). In the mid-19th century, Tara already had two candle factories of its own (Tara v XVI– XIX vekakh…, 2014: 143).

Availability of a clay candlestick in the filling of the dwelling in the village of Ananyino (see Fig. 2, 5 ) described above suggests an extraordinary social status of its owner and probably his literacy. The item was made of clay and was polished, which made it look like metal. The candlestick has been broken into two parts; the upper part was in the form of a narrow glass on high stem, with a platform below the bottom of the container for melted wax. The height of the preserved part was 9.1 cm; height of the bowl was 5 cm; diameter along the top was 3 cm; diameter of the platform was 4.5 cm. The thickness of the wall was 0.3 cm. The lower part was 3.5 cm high; it had remains of a stem (0.8 cm in diameter) and base (8 cm in diameter) in the form of a saucer with low, slightly expanding walls. The total height of the candlestick could have been 14–15 cm.

Another item, which may be related to the topic under discussion, is a bone case looking like a round tube with the thread for caps at the ends (see Fig. 2, 6 ), which was discovered in Tara. Its length was 8.7 cm; inner diameter was 1.4 cm. Together with caps, its length could have exceeded 10 cm. The surface was covered with ornamentation of zigzag lines most likely carved with a knife. This item has become obsolete due to abrasion of the thread from one edge and possibly loss of one cap.

Such a small case could not store large scrolls, but was suitable for storing notes on 10 × 10–11 cm sheets*.

The case was found in a dwelling (closed complex) dated to the 17th century by the coins of Tsar Mikhail I (Tataurov S.F., Tataurov F.S., 2021). Taking into account sabers, parts of firearms, and combat arrowheads also discovered there, the authors of the excavations suggested that the dwelling belonged to a junior military commander. He could carry out orders for delivering reports, which is confirmed by a penknife and bone case described above (Ibid.: 672).

It is unlikely that this case was used for keeping other items. For example, sewing needles are short, and they had special needle cases, which were widespread among the indigenous population and are available in the Tara collection as soldered bronze or silver tubes (Tataurov S.F., Tikhonov, 1996: 77). Knitting needles were made of bone at that time, and they had different lengths and thicknesses. In addition, knitting needles were widespread products which didn’t not require careful storage. A possible alternative related to literacy was storing writing pens, such as those found in Mangazeya.

Thus, the accumulated archaeological evidence and currently available historical sources make it possible to draw a conclusion about literacy and numeracy skills in the 17th–18th centuries both among the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts, and among the Russian Siberian population as a whole.

Conclusions

Throughout the 17th century, the level of literacy among the subjects of the Muscovite State, excluding the clergy and tsar’s officials, was generally not very high. The share of literate persons among the noble servicemen in various regions was 25–45 % (Lapteva, 2010: 509–511). This situation persisted until the mid-18th century despite the attempts of Peter I to introduce secular “elementary schools” for the representatives of different social classes.

Siberia was no exception, although its population class structure comprised servicemen of different nationalities and social statuses, including people from the European countries, such as Germans, Poles, as well as Baltic peoples, which were generically called “the Lithuanians”. They were not only well-familiar with military affairs, but were also quite educated (Goncharov, Ivonin, 2006: 23–30).

It is challenging to assess the actual literacy level of the Siberian population even in a particular region. Written sources provide information on the needs and provision of the Tara population with stationery supplies (ink, paper). It is supplemented by archaeological evidence of inkpots, wax tablets and styluses, paper, quills, and ink needed for writing. There is evidence demonstrating the tendency to improve the “working conditions” and use a more progressive way of lighting.

Archival documents contain rich data on various aspects of life and occupations of the Tara residents. For example, the Tobolsk nobleman, Dmitry Rukin, who was appointed in 1728 the governor of Tara, was no stranger to the “fundamentals of education”. Along with religious books, his personal library contained two books of secular nature: “The Book of Moral Stories” and “The Book of Theatron”* (Sluzhiliye lyudi Sibiri…, 2019: 768). However, these sources do not answer the question of how the main part of the servicemen, except for the literate and those for whom other persons signed, acknowledged the receipt of their salary.

Archaeological finds discovered both in Tara and Ananyino disclose social features for individual representatives of the service population and raise some questions about the purpose of items that can be associated with board abacuses, and the item that we identified as a letter case. Notably, earlier, a leather case for a compass was found in Tara (Osipov et al., 2017), which testifies to the knowledge of navigation.

This comprehensive analysis of archaeological, written, and historical sources has revealed the level of education among the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts in the 17th–18th centuries. The study has also shown the material markers of literacy and numeracy in the cultural layers of the sites, approximate number of literate people in different strata of society, their social function, degree of representativeness of the written documents, as well as role and importance of archaeological evidence.

Acknowledgment

This study was performed under Public Contract FWZG-2022-0005 “Research of Archaeological and Ethnographic Sites in Siberia in the Period of the Russian State”.

Список литературы Literacy and numeracy skills of the inhabitants of Tara and its rural districts in the 17th and 18th centuries

- Balyunov I.V. 2014 Materialnaya kultura naseleniya goroda Tobolska kontsa XVI-XVII veka po dannym arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy: Cand. Sc. (History) Dissertation, vol. 2. Novosibirsk. EDN: YFKXKR

- Belovinsky L.V. 2007 Illyustrirovanniy entsiklopedicheskiy istoriko-bytovoy slovar russkogo naroda XVIII - nachalo XX v. Moscow: Eksmo.

- Chernaya M.P. 2015 Voyevodskaya usadba v Tomske. Tomsk: D'Print.

- Evangeliye. 1681 Moscow: Pechatnyi dvor. Proekt ".Yavit miru Siyskoye sokrovishche": Antoniyev-Siyskiy monastyr: Iz proshlogo - v budushcheye". URL: https://siya.aonb.ru/index.php?num=2586 (Accessed December 2, 2021).

- Gogolev A.K. (s.a.) Formaty russkikh rukopisnykh knig; sootnosheniye sistem izmereniya osnovnykh formatov knig. URL: http://www.lifeofpeople.info/LibraryOwnData/Conspect/22_76_21_s1.pdf (Accessed February 2, 2022).

- Goncharov Y.M., Ivonin A.R. 2006 Ocherki istorii goroda Tary kontsa XVI – nachala XX v. Barnaul: Az Buka.

- Gudkov A.G. 2014 Trost i svitok: Instrumentariy srednevekovogo knigopistsa i ego simvoliko-allegoricheskaya interpretatsiya. Vestnik Pravoslavnogo Svyato-Tikhonovskogo gumanitarnogo universiteta. Ser. V: Voprosy istorii i teorii khristianskogo iskusstva, iss. 1 (13): 19–46.

- Krikh A.A. 2016 Russkoye naseleniye Tarskogo Priirtyshya: Istorikogenealogicheskiye ocherki (XVII – nachalo XX veka). Omsk: Nauka.

- Lapteva T.A. 2010 Provintsialnoye dvoryanstvo Rossii v XVII veke. Moscow: Drevlekhranilishche. Lokhnesskoye chudo. Anekdoticheskiy sluchay, proisshedshiy s lyubitelyami istorii. (s.a.) URL: https://7iskusstv.com/2013/Nomer8/Cajger1.php (Accessed January 25, 2022).

- Miller G.F. 1999 Istoriya Sibiri, vol. 1. Moscow: Vost. lit.

- Osipov D.O., Tataurov S.F. Tikhonov S.S., Chernaya M.P. 2017 Leather artifacts from Tara, Western Siberia, excavated in 2012–2014. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 45 (1): 112–120.

- Psaltyr. 1636 Moscow. URL: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000199_000009_02000026822/ (Accessed December 14, 2021).

- Rabinovich M.G. 1949 Raskopki 1946–1947 gg. v Moskve na ustye Yauzy. In Materialy i issledovaniya po arkheologii Moskvy, vol. 2. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 5–43. (MIA; No. 12).

- Simonov R.A. 2010 K istorii scheta v dopetrovskoy Rusi. In Matematika v vysshem obrazovanii, No. 8. Review of Tsaiger M.A. Arifmetika v Moskovskom gosudarstve XVI veka. Beer Sheva: Berill, pp. 135–142.

- Slovar russkogo yazyka XI–XVII vv. 1980, 1988 Iss. 7: K–Kraguyar. Iss. 14: Otrava–Persona. Moscow: Nauka.

- Sluzhiliye lyudi Sibiri kontsa XVI – nachala XVIII v.: Entsiklopedicheskiy slovar. 2019 I.N. Kamenetsky (ed.). Moscow, St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

- Spassky I.G. 1952 Proiskhozhdeniye i istoriya russkikh schetov. In Istorikomatematicheskiye issledovaniya, iss. V. Moscow: Gos. izd. tekhniko-tekhich. lit., pp. 269–420.

- Stolyarova L.V., Kashtanov S.M. 2010 Kniga v Drevney Rusi (XI–XVI vv.). Moscow: Ros. Fond sodeistviya obrazovaniyu i nauke. Tara v XVI–XIX vekakh – Rossiyskaya krepost na beregu Irtysha. 2014 Omsk: Amfora.

- Tataurov F.S. 2020 Perstni i koltsa kak element sotsialno-kulturnogo oblika russkogo naseleniya Zapadnoy Sibiri XVII–XIX vv. (po materialam arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy). In Trudy VI (XXII) Vseros. arkheol. syezda v Samare, vol. III. Samara: Samar. Gos. Sots.-Ped. Univ., pp. 55–56.

- Tataurov S.F. 2017 Arkheologicheskiye svidetelstva torgovykh otnosheniy v g. Tare v XVII–XIX vv. Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Istoriya, No. 46: 103–109.

- Tataurov S.F. 2019 Osveshcheniye zhilykh, administrativnykh i khramovykh kompleksov v gorode Tare v XVII–XIX vv. Vestnik arkheologii, antropologii i etnografi i, No. 1 (44): 37–44.

- Tataurov S.F., Fedotova I.V. 2018 Arkheologicheskiye materialy iz raskopok v g. Tare v sobranii Omskogo gosudarstvennogo istoriko-krayevedcheskogo muzeya (raskopki 2009–2017 gg.). Katalog. Omsk: Zolotoy tirazh.

- Tataurov S.F., Tataurov F.S. 2021 Zhiloy kompleks XVII veka v gorode Tare v issledovaniyakh 2021 goda. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXVII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 669–673.

- Tataurov S.F., Tikhonov S.S. 1996 Mogilnik Bergamak II. In Arkheologo-etnografi cheskiye kompleksy: Problemy kultury i sotsiuma (kultura tarskikh tatar), vol. 1. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 58–84.

- Tataurova L.V. 2017 “V gornitse moyei svetlo”: Osvetitelniye pribory v russkikh zhilishchakh (po materialam arkheologicheskikh kompleksov XVII–XVIII vv. Omskogo Priirtyshya). In Kultury i narody Severnoy Yevrazii: Vzglyad skvoz vremya. Tomsk: D’Print, pp. 167–171.

- Tataurova L.V. 2018 Evolyutsiya zhilishchnogo kompleksa (po materialam raskopok russkoy derevni XVII–XVIII vekov Ananyino-1). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXIV. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 342–346.

- Tataurova L.V. 2021 Metodicheskiye aspekty formirovaniya arkheologicheskogo istochnika Novogo vremeni. Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Istoriya, No. 69: 67–72.

- Tataurova L.V., Krikh A.A. 2015 Sistema obespecheniya sibirskoy derevni Ananyino v XVII–XVIII vv. (po arkheologicheskim i pismennym istochnikam). Byliye gody, vol. 37 (3): 479–490.

- Tataurova L.V., Nekrasov A.E. 2021 Promysel pernatoy dichi russkim naseleniyem Tarskogo Priirtyshya v XVII–XIX vv.: Pismenniye i arkheologicheskiye istochniki. Stratum plus, No. 6: 75–86.

- Tataurova L.V., Sopova K.O. 2021 Russkaya derevnya Ananyino: Arkheologicheskiye khronologii. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXVII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 678–684.

- Tsvetkova G.Y. 1994 Gorod na reke Arkarke. In Tarskaya mozaika: (Istoriya kraya v ocherkakh i dokumentakh 1594–1917 gg.). Omsk: Kn. izd., pp. 6–45.

- Vilkov O.N. 1967 Remeslo i torgovlya Zapadnoy Sibiri v XVII v. Moscow: Nauka.

- Vizgalov G.P., Parkhimovich S.G. 2008 Mangazeya: Noviye arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya (materialy 2001–2004 gg.). Yekaterinburg, Nefteyugansk: Magellan.

- Vizgalov G.P., Parkhimovich S.G. 2013 Mangazeya: Noviye arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya (materialy 2005–2010 gg.). Yekaterinburg, Nefteyugansk: Institut arkheologii Severa.

- Vizgalov G.P., Parkhimovich S.G. 2017 Mangazeya: Usadba zapolyarnogo goroda. Nefteyugansk, Yekaterinburg: Karavan.

- Zapiski puteshestviya akademika Falka. 1824 St. Petersburg: [Pri Imp. Akademii nauk]. (Polnoye sobraniye uchenykh puteshestviy po Rossii, izdavayemoye Imperatorskoyu Akademiyeyu nauk, po predlozheniyu yeyo prezidenta; vol. VI).

- Zinyakov N.M. 2017 Chernometallicheskiye izdeliya poseleniya Ananyino v Tarskom Priirtyshye: Tekhnologicheskaya kharakteristika. In Kultura russkikh v arkheologicheskikh issledovaniyakh. Omsk: Nauka, pp. 427–438.