Medieval sites of Tara region, the Irtysh basin: origin, chronology, cultural and ethnic attribution

Автор: Tataurov S.F., Tikhonov S.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145405

IDR: 145145405 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.1.103-112

Текст статьи Medieval sites of Tara region, the Irtysh basin: origin, chronology, cultural and ethnic attribution

In the 8th to 12th centuries, Turkic-speaking inhabitants of the steppe regions of eastern Altai and the upper Irtysh migrated to the forest-steppe and the southern taiga subzone of the Middle Irtysh. Inter-ethnic contacts resulted in the formation of Turkic-Ugric population groups in the said zones. Specialists attribute the archaeological sites left by them to the Ust-Ishim culture*.

A part of the Ugric population that inhabited this territory was, probably, forced to the lower Irtysh basin. This article analyzes bronze artworks from the undescribed

Region (1983: 14–17). It is dated to the 9th to 13th centuries. The vast majority of sites belonging to this culture are located on the banks of the Irtysh River, from the Tara River’s mouth in the south to the Tobol River’s mouth in the north; and in the lower reaches of the right Irtysh tributaries (Tara, Shish). Some sites are located beyond the limits of the cultural area, namely: in the Vasyugan upper reaches in the east, near the Tavda River, a Tobol tributary, in the north-west, and between the mouths of the Tobol and Demyanka in the north. In the south, Ust-Ishim materials are encountered in the forest-steppe zone to the south of Tara.

Archaeological complex at Aitkulovo

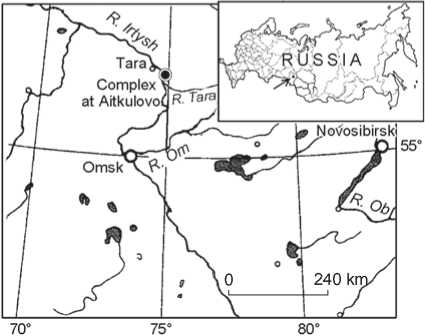

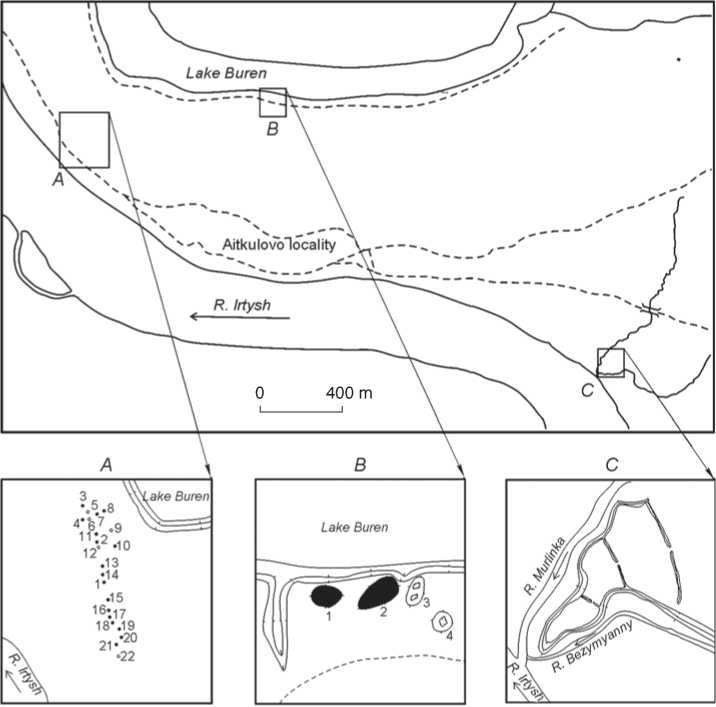

The sites in the neighborhood of Aitkulovo village (the Tarsky District of the Omsk Region) are located on the rock terrace of the Irtysh’s right bank (Fig. 1, 2). In 1961– 1962, V.I. Matyushchenko discovered a medieval fortified settlement of Murlinka (Fig. 2, B ), a kurgan cemetery near Lake Buren—the Murlinka kurgans (Fig. 2, A ), and a cemetery on the bank of the Irtysh—the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh River (Fig. 2, B ). Chagaeva conducted excavations at the last-mentioned burial ground in 1965, 1967, and 1976, and at the fortified settlement in 1965. In 1983, Matyushchenko continued studying the Aitkulovo fortified settlement (1983). We assume that all sites were left by a single group of population. This presumption is based upon the similarity of finds (artifacts made of ceramics, iron, bronze, bones, etc.) from the fortified settlement and from the cemeteries, in terms of shape and ornamentation of ceramic ware, and types of metal and bone weapons and tools.

This article focuses on the artifacts found in the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh River. Twenty-two features were located on an elongated, low dune in the river. In the northern part of the cemetery, mounds of kurgans 4 and 7–10 were located outside the main line (Fig. 2, B ). All kurgans 7 to 14 m in diameter with a height up to 1 m had a hemispherical shape. Robber pits were recorded in all burial mounds.

Over four years of work, Chagaeva excavated 17 kurgans (1962 – 4, 1965 – 1–3; 1967 – 7, 8, 10, 11, 21; 1976 – 13–20). The materials were partially described (Chagaeva, 1973).

Burial rite

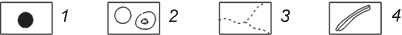

The above sizes of kurgans should be deemed conditional: artifacts found in the burial mounds are concentrated only in their central parts; consequently, the mound diameters were, probably, smaller in ancient times. The majority of kurgans accommodated a single burial under the mound (kurgans 1–4, 7, 10, 11). Three kurgans accommodated 2 buried persons each. Judging by the burial goods, a man and a woman were buried in two of them (kurgans 8 and 13), and a woman and a child in one burial mound (kurgan 6). In kurgan 21, three burials were discovered (Fig. 3). Kurgan 9 contained, probably, three burials, as

Fig. 1 . Arrangement of the archaeological complex at Aitkulovo.

the field inventory of this kurgan shows a relevant record; though the field journal mentions only one grave. Kurgan 12 could, possibly, have contained a cenotaph: there is a record indicating that no skeleton was discovered.

Burial pits are absent. Burials were predominantly made 20–25 cm above the level of the virgin soil (kurgans 2, 3, 10, 11), and one burial (kurgan 1) was performed on the virgin soil. We suppose that the deceased were buried on the ancient daylight surface, which has been transformed into buried soil over the past centuries.

In the mounds of kurgans 1–3, 7, 10, 11, 20, traces of fire (charred earth), or charcoal, ash, and burned bones were discovered. The mounds of kurgans 2–4, 6, 7, 9–11, 13, 14, and 20 contained funerary offerings to the diseased: ceramic vessels, iron arrowheads, celts, bits, bronze ornaments, and beads.

The deceased were buried in supine extended positions according to the inhumation rite. Some of them are oriented to the NW (kurgans 1, 2, 11), and one of them to the W (kurgan 9). The majority of burials contain grave goods, such as cult artifacts cast in bronze, weapons, tools, stirrups, bits, etc. Above a burial, a kurgan was erected, without a ditch or structures inside the mound. In kurgan 2 only, an oval birch-bark sheet 3.5 × 1.8 cm was recorded. Horse teeth and bones, ceramic vessels, bits, weapons, and ornaments were placed in or on the burial mound. In kurgan 2, a birch-bark box was put in the grave or in the mound. Though the use of fire during funeral ceremonies has been established, it is impossible to determine the details of the rite (secondary cremation, partial burning, filling up with charcoal or ash).

Analysis of materials

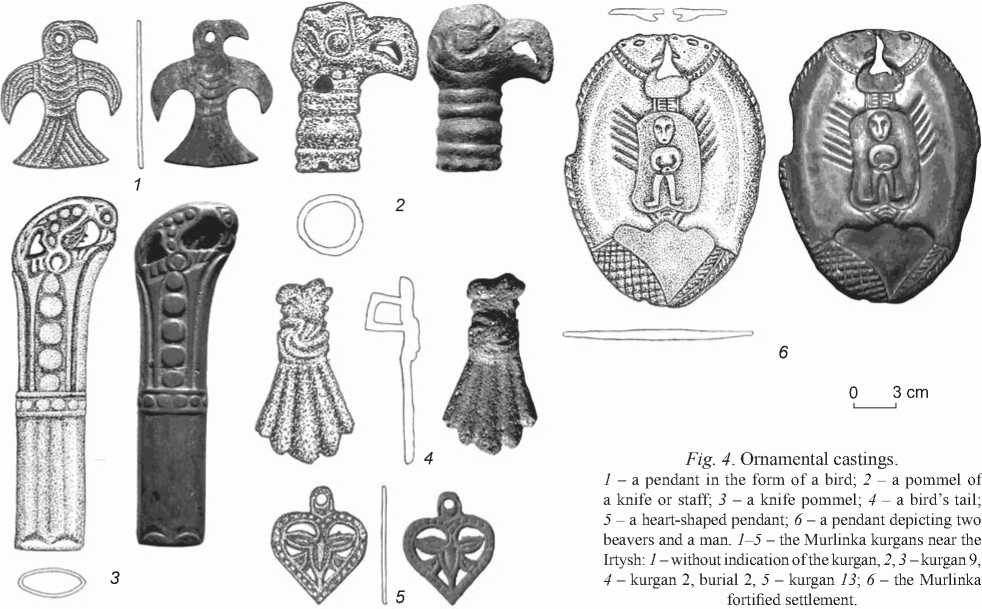

Knife-po mmels and pendants—bronze casting. A pommel cast in the volume-openwork manner, with

Murlinka kurgans Murlinka kurgans Murlinka fortified near the Irtysh River (near Lake Buren) settlement

Fig. 2 . Features of the complex.

1 – an excavated kurgan; 2 – an unexcavated kurgan; 3 – forest roads; 4 – a trench and earthworks.

Fig. 3 . General plan ( A ) and layouts of burials ( B ) of kurgan 21.

1 – a sector number; 2 – a pit in the virgin soil; 3 – boundary of a grave in the virgin soil; 4 – a conventional boundary of the grave;

5 – ceramics in the burial mound; 6 – human bones.

small ornamentation (Fig. 4, 3 ). A very similar artifact was discovered at the cemetery of Ust-Balyk (the Nefteyugansky District, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug of the Tyumen Region) (Semenova, 2001: 98).

A pendant in the form of a bird with outspread wings and tail, and with its head turned to the right (see Fig. 4, 1 ). The entire figurine was covered with ornamentation symbolizing the bird’s feathering. V.A. Mogilnikov associates it with the Potchevash culture (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 190).

A heart-shaped pendant with pearl ornamentation along the edge, and with an image of a flower with three petals at the center (Fig. 4, 5 ). D.G. Savinov attributes pendants with similar shape and decoration to the Srostki culture (9th to 10th centuries) (1984: 122). Mogilnikov considers the pendant to be a Potchevash one (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 190). According to Konikov, such ornaments are typical of the entire period of existence of the Ust-Ishim culture (2007: Fig. 226). In our opinion, artifacts of this type existed in this territory for a more prolonged period. Pendants of identical shape have been found at the Nadezhdinka IV cemetery (14th to 16th centuries) and in the town of Tunus (late 16th century), which are located on the flood plain of the right tributary of the Tara, 2 km above its mouth (the Muromtsevsky District of the Omsk Region) (Tataurov, 2002).

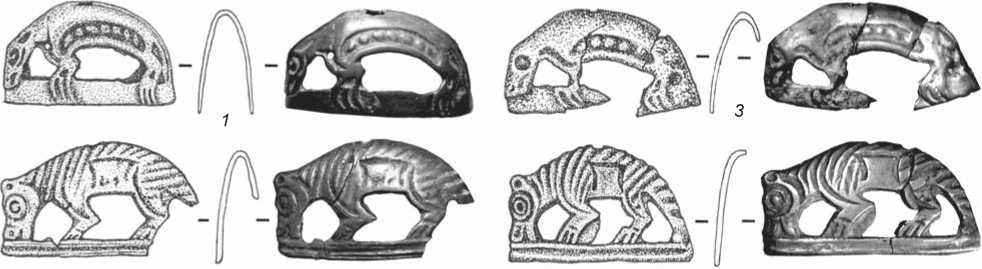

Pendants representing a pangolin or a predatory animal (four intact items and several fragmented ones) are bellshaped; the animal is rendered symbolically (Fig. 5). Two items that are three-dimensional representations have each only a row of “pearls” on the animal’s side, while the head, paws, and tail are worked out in detail (Fig. 5, 1, 3). In our view, these pipe-shaped pendants depict a pangolin. Almost identical representations are stored in the Surgut Local Lore Museum (Surgutskiy kraevedcheskii muzey…, 2011: Fig. 188, p. 82). V.I. Semenova reasons that similar items were worn by inhabitants of taiga regions of Western Siberia from the first half of the 9th century to the 12th century (2001: 75). One more pendant depicting a pangolin was found at the Argaiz I cemetery, in the northern Omsk Region (Konikov, 2007: Fig. 262). Two pendants show an animal looking like a wolverine and depicted in the same posture as the pangolin, though in a different manner. Each figurine is entirely covered with “skeleton” lines; U-shaped signs are seen on the sides (Fig. 5, 2, 4).

Pipe-shaped beads depicting pangolins or predatory animals are widely represented in the taiga and foreststeppe zones of the Trans-Urals, Western and Southern Siberia. Recently, the number of sites containing such items has considerably increased. The closest parallels to these artifacts are pendants from cemeteries of the Surgut region of the Ob (Semenova, 2001: 89).

A decorative element (a pendant?) in the form of a bird’s tail, tied in a large symbolically-rendered knot (see Fig. 4, 4 ). A large U-shaped fastening clip is on the back side of the item.

Pommel of a knife or a staff in the form of the head of a carnivorous bird (a sea eagle?) (see Fig. 4, 2 ). A nearly

0 3 cm

Fig. 4 . Ornamental castings.

1 – a pendant in the form of a bird; 2 – a pommel of a knife or staff; 3 – a knife pommel; 4 – a bird’s tail;

5 – a heart-shaped pendant; 6 – a pendant depicting two beavers and a man. 1–5 – the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh: 1 – without indication of the kurgan, 2 , 3 – kurgan 9, 4 – kurgan 2, burial 2, 5 – kurgan 13 ; 6 – the Murlinka fortified settlement.

J 4

4 0 3 cm

Fig. 5. Representations of a pangolin ( 1 , 3 ) and a wolverine ( 2 , 4 ).

identical pommel was found by Konikov when excavating the Kipy III kurgan cemetery, in kurgan 2, burial 2 (the Tevrizsky District of the Omsk Region) (2007: 206, fig. 257).

Pendant depicting two beavers and a man (see Fig. 4, 6 ) (Shemyakina, 1980: 28–33). Its closest compositional analog is a plaque from the Vasyugan hoard that depicts a man with a mask on his chest at its center, and a bird and a sable on its sides (Chindina, 1991: 69, 162, 170). Mogilnikov has described a pendant representing a similar subject and showing figures of beavers and a human mask between them; the pendant was accidentally found in the Ust-Ishimsky District of the Omsk Region (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 199, fig. LXXXII, 12 ; p. 330).

The two above artifacts are solid-cast copper items. The casting was performed in coarse-grained sandstone molds, which determined the surface roughness of the artifacts. After casting, the surface was not treated.

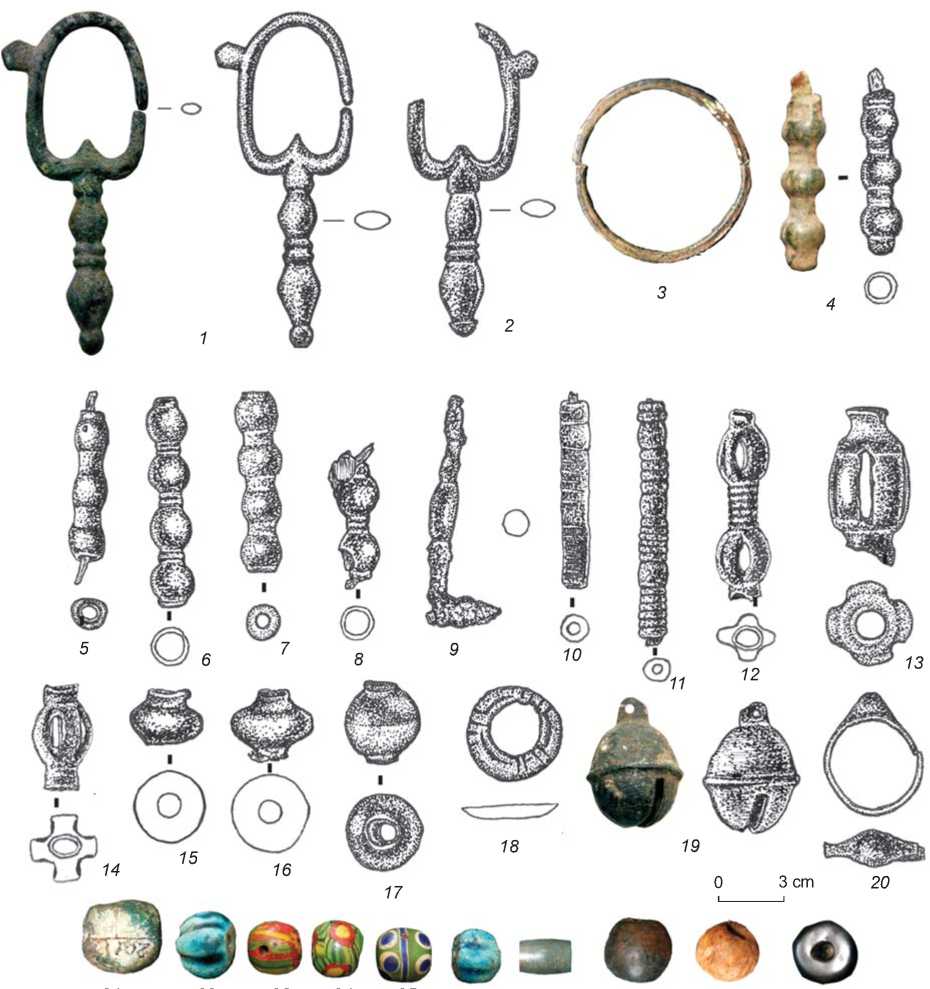

Pendants. Parts of dangle pipe-shaped pendants are represented by two types: tubular solid-cast two- and four-piece parts, and spherical ellipsoid parts, different in their proportions and manufacturing technology (from casting in a single mold to joining two parts by riveting (Fig. 6, 15–17 ). The collection consists of pear-shaped pendant-buttons, a pear-shaped small bell with a linear slot and a horizontal belt (Fig. 6, 19 ), and a flat ring with an ornament of longitudinal and transverse lines (Fig. 6, 18 ). According to Konikov, such small bells gained widespread use in the early 2nd millennium AD (2007: 435, fig. 262).

Nine pendant-earrings have been discovered. These are similar to the earrings in their shape, but small in size, which prevents from assigning them to the bracelets made of wire with a round cross-section. The items are made of bronze pins, some of which are forged together (3 spec.). These vary from 3 to 8 cm in diameter. Some of them were most probably used as earrings, and others for decoration on clothes.

Pendants, each with a ring, a pin, and a lug. Three items have been discovered (Fig. 6, 1, 2). A similar pendant was discovered by Konikov at the Aleksandrovka I kurgan cemetery, and assigned by him to the last development stage of the Potchevash culture. In his opinion, such ornaments are Finno-Ugric, they were widespread from the Ob basin to the eastern boundary of Old Rus (2007: 223).

Finger-ring. The ornaments of this type were widespread till the 19th century. Judging by the symbolically-rendered “pearls”, the finger-ring is for a female (Fig. 6, 20 ). Such finger-rings were found in female burials of the 17th–18th century cemetery of Bergamak II, near the Tara River (Tataurov, Tikhonov, 1996: 82–83). The presented assemblage of ornaments is common for the forest-steppe belt of Western Siberia (Chindina, 1991; Konikov, 2007).

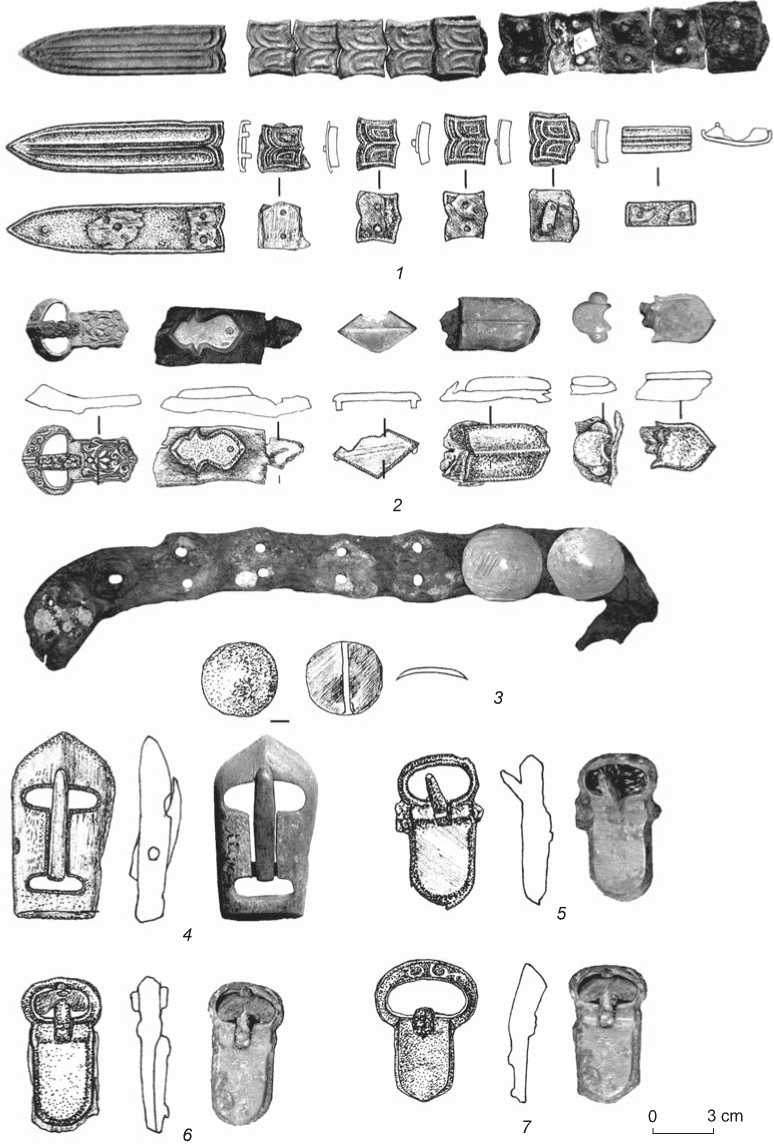

Belt sets. A belt set, comprising an elongated tip with an ornament in the form of long longitudinal stripes and clips, which were fastened tightly together, was made of white metal (Fig. 7, 1 ). The clips are decorated with representations of two wide radiating leaves. An identical set from the Baltargan cemetery is exhibited in the Anokhin Museum in Gorno-Altaisk (Hudiakov, Kocheev, Monosov, 1996: Fig. 1). Similar belts are abundant at the Altai funerary sites (Alekhin, 1996: Fig. 12; Neverov, Gorbunov, 1996: Fig. 6, 7; Tishkin, Gorbunov, 2000: Fig. 2).

A belt set with figured onlays of various shapes (strict geometric plates, as well as symbolically-rendered heartshaped and segment-like ones) (Fig. 7, 2 ). Belts with such sets of plaques were widespread in the Upper Irtysh basin (Arslanova, 1972: 56). Such diversity of onlays on waist belts with plates is typical of the belts pertaining to the Ust-Ishim culture (Konikov, 2007: 422).

A belt set with round silver plaques fastened by two small nails (Fig. 7, 3 ). A similar belt was found at the Sabinka I cemetery in Khakassia (Dobzhansky, 1990: 40, 138; Savinov, Pavlov, Pauls, 1988: 83–103). Such a belt is present in the materials from burial 1 in kurgan 13 of the Ust-Ishim I cemetery in the Irtysh basin (Konikov, 2007: Fig. 200).

23 24 25 26 27

Fig. 6 . Ornaments.

1 , 2 – pendants; 3 – a pendant-earring; 4–11 – tubular pipe-shaped pendants; 12–17 – volumetric pendants; 18 – a flat ring with cut-marks; 19 – a small bell; 20 – a finger-ring; 21–30 – paste beads.

1–18 , 20–30 – the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh: 1 , 2 , 10–15 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26–30 – kurgan 20, 4–9 , 20 – kurgan 4, 16 – kurgan 9, 17 – kurgan 4, 18 – kurgan 7, 25 – kurgan 6, 19 – the Murlinka kurgans.

The sets of belt onlays described above are different in their style and manufacturing technique. Buckles serve to unify them (Fig. 7, 4–7). All the buckles found in the Murlinka burials are bimetallic (bronze with an iron tang) and miniature (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 198). Such buckles have been found in burials of many cemeteries dated to the first third of the 2nd millennium AD in the Tara region of the Irtysh: in particular, at the cemeteries of Alekseevka XX and XXVI in the Tara lower reaches (Tataurov, 2001: 199; 2003: 69). Konikov assigns the items of this type to the period of the Ust-Ishim culture (2007: 422).

Beads. The collection contains eight glass (paste) beads and two ceramic ones (see Fig. 6, 21–30 ). All paste beads, apart from the cylindrical one (carved from a pipe),

Fig. 7. Belt sets ( 1–3 ) and buckles ( 4–7 ).

1–3 , 5–7 – the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh: 1–3 – kurgan 23, 5 – kurgan 20, 6 – kurgan 7, 7 – kurgan 2;

4 – the Murlinka kurgans.

are made with the curling technique. Such set of beads is common for the sites located in the forest-steppe and taiga Irtysh basin (Ibid.: 225–226) and in the Surgut region of the Ob (Semenova, 2001: 90–92). Mogilnikov points out that the beads were manufactured mainly in Old Rus and were of considerable value (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 199).

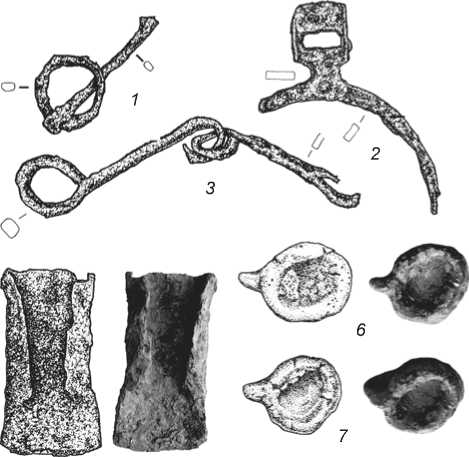

Horse harness. Ring bits are made of iron pins; the junctions between the rings or mouthpiece shanks

4 5 0 3 cm

Fig. 8. Details of horse harness ( 1–3 ) and tools ( 4–7 ).

1 , 3 – bits; 2 – stirrup; 4 , 5 – celt; 6 , 7 – clay ladles. 1–5 – the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh: 1 , 2 – kurgan 1; 3 – kurgan 6; 4 , 5 – kurgan 4;

6 , 7 – the Murlinka fortified settlement.

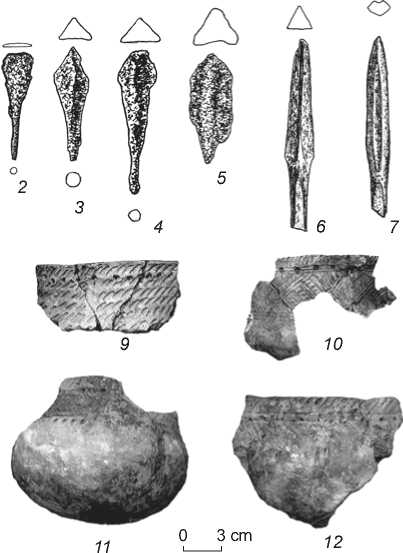

Fig. 9. Arrowheads ( 1–7 ), a knife ( 8 ), and ceramic vessels ( 9–12 ).

1–5 – iron arrowheads; 6 , 7 – bone arrowheads; 8 – an iron knife; 9–12 – vessels. 1–12 – the Murlinka kurgans near the Irtysh: 1 – kurgan 12; 2 , 5–7 , 9 – kurgan 4; 3 , 4 – kurgan 23; 8 – kurgan 7; 10 – kurgan 6; 11 – kurgan 11; 12 – kurgan 8.

are poorly worked out. These were widespread in the Irtysh basin throughout the entire 2nd millennium AD (Fig. 8, 1 , 3 ). Horse bits with free rotating ring cheekpieces appeared in the Irtysh basin in the 10th century (Ibid.: 198).

A stirrup with a strap attachment in the form of a clip in a specially designated upper portion, with a flat crosssection in the upper part of the shanks, and roundish towards the pad. The pad itself is absent (Fig. 8, 2 ). The same fragment is provided, unfortunately without indicating the location of the find, by Konikov in his monograph devoted to the Omsk region of the Irtysh in the Middle Ages (2007: Fig. 210). Stirrups with nearly archshaped shanks, with a wide foot-plate and a neck-plate, and a rectangular opening for the stirrup-strap, are typical of the second half of the 8th century to the first half of the 9th century (Finno-ugry…, 1987: 189, pl. LXXVIII, 1 ). Identical artifacts were discovered at the southern Siberian sites (Kubarev, 2005: 120, 209, 309).

Celts. There are eight items, similar in their type and manufacturing technology, but different in size (see Fig. 8, 4 , 5 ). According to Konikov, elongated items could have been used as small hoes (2007: Fig. 167). However, celts-hoes found at the Bergamak II site, in the Irtysh basin, had a more elaborated working portions, which were wider and thinner (Tataurov, 1999: 118). Such tools are known from the sites of the Ust-Ishim culture (Konikov, 2007: Fig. 164, 165).

Clay ladles for molten metal and a crucible. These artifacts were found during excavations at the Murlinka fortified settlement in 1965. Both ladles had tails in the form of handles (Fig. 8, 6 , 7 ). The use of the items is evidenced by bronze scale on their inner walls and by traces of ceramic blistering on the outer walls. Such clay ladles for molten metal, and crucibles, are typical of the Ust-Ishim settlements (Ibid.: Fig. 176, 177).

Weapons. Five iron (Fig. 9, 1–5 ) and two bone stemmed (Fig. 9, 6 , 7 ) arrowheads, as well as one iron knife (Fig. 9, 8 ), were found. Two iron arrowheads are flat (one of these is diamond-shaped, the other is chisel-shaped); three arrowheads are trihedral, with the center of gravity displaced to the killing portion. One bone arrowhead is trihedral, the other is tetrahedral. The stemmed knife has a straight, evenly tapered blade. Arrows of such type appeared in the Irtysh basin in the late 9th century AD, during migrations of population from the area of distribution of the Srostki culture (Savinov, 1984: 104–106).

Ceramic items. All vessels are round-bottomed, and jar-shaped, with slightly bulging bodies. These are carelessly made of poorly kneaded paste, and slightly under-dried. Ornaments composed of oblique combstamp imprints, forming parallel rows, “herringbones”, or more complex geometric compositions, are arranged along the rims and in the upper portions of the bodies.

Cannelures or rows of pits serve as separators. Certain decoration elements in the form of arcs or rows of parallel depressions are below the ornamentation zones (Fig. 9, 9 , 11 ). The ware is similar to the Ust-Ishim pottery (Bolshanik, Zhuk, Matyushchenko, 2001: 166–169; Konikov, 2007: Fig. 137).

Dating, and cultural and ethnic attribution

In general, finds from the cemeteries under consideration, along with the Ust-Ishim materials from the Murlinka fortified settlement, allow a conclusion to be drawn about the formation of the complex in the 10th century, within one or two centuries after the arrival of the Turks in the Middle Irtysh basin. From our point of view, this is evidenced by a change in the burial rite, i.e. transition from cremation to inhumation. However, the turkization process in this territory had not been completed by that time.

Migration by the Turks caused replacement of population in the Middle Irtysh basin. Konikov reasons that the northern (the Middle Irtysh) version of the Kimek-Kipchak culture was established in the forest-steppe and southern-taiga Irtysh region with the participation of Turks (2007: 253–258). Upon the arrival of the Turks, a smaller part of local population was forced out, while the predominant part underwent assimilation. The latter was reflected in all segments of the material and intellectual culture of the Irtysh basin inhabitants in the late 8th to the 10th century. The items manufactured by Irtysh craftsmen suggest deep interpenetration between the cultures of migrants and that of the local population, and profound influence from the southern Siberian component on formation of the Middle Irtysh population’s culture.

Analysis of bronze castings allows the conclusion to be drawn that development of bronze casting technologies and design subjects in the Tara region of the Irtysh proceeded under the influence of traditions that formed in the Perm Territory and in the Kama and Lower Ob regions (in the middle of the 1st to the early 2nd millennium AD). In these territories, artifacts similar to the Irtysh ones were found, in terms of the volume-openwork casting technology and anthropo- and zoomorphic images design. This was also true for the Middle Ob basin, where artifacts, although being reminiscent of the Irtysh ones, are characterized by a variety of animal images in decoration, a greater realism of representations (especially anthropomorphic ones), and by the volumecasting technique. According to Chindina, figurines from the Irtysh basin are considerably less different from those found in the Ob basin than from the Perm castings (1991: 65). The close similarity between the artifacts can be explained by sustainable relations between the inhabitants of the Ob and Irtysh regions, which were maintained directly through the Vasyugan Swamp. Contacts between the local residents and newcomers became more intense after the resettlement of Ugrian people to the southerntaiga and taiga Ob-Irtysh interfluve from the foreststeppe zone of Western Siberia under the influence of southern migrants in the late 9th century AD. Obviously, the complex of Murlinka kurgans in the Irtysh basin was situated at the intersection of trade routes, and, possibly, also migration flows.

Conclusions

In the late 1st millennium AD, a new population was formed in the Middle Irtysh region under the influence of the turkization processes. This population may be associated with the Kimeks and Kipchaks, whose archaeological sites belonged to the Srostki culture. The new population, which included groups of local Ugrians, maintained ties with inhabitants of the Ob region, the northern taiga of the Kama region, and the lower reaches of the Ob (Konikov, 2007: 248–249, 256).

According to a number of researchers, in the early Middle Ages the following archaeological cultures existed sequentially in the Omsk region of the Irtysh: Potchevash, Ust-Ishim; and during the advanced Middle Ages, groups of Siberian Tatars were formed. In our opinion, at the end of the Potchevash period, a new, basically Turkicspeaking, population was formed in the forest-steppe and southern-taiga Irtysh region as a result of Srostki people’s arrival. This new population left sites belonging to the Middle Irtysh Kimek-Kipchak culture. This culture, from our point of view, is in no way associated with the Ust-Ishim culture. It may be concluded that the Ust-Ishim archaeological culture disappeared, because from the beginning of the 1st millennium AD, the Middle Irtysh area became a part of the Kimek-Kipchak world, which is genetically related to the Srostki culture.