Metaphorical terminology in ancient texts of traditional Chinese medicine: problems of understanding and translation

Автор: Sun Q., Karabulatova I., Zou J., Kuo Ch.

Журнал: Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 2: Языкознание @jvolsu-linguistics

Рубрика: Межкультурная коммуникация и сопоставительное изучение языков

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.23, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The author's hypothesis proceeds from the position that the ancient treatises of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) describe metaphorically an ethnocultural understanding of neuro-linguistic and psychophysiological processes in the human body from the perspective of communication between large and small. TCM terms are medical concepts that also contain deep philosophical and linguistic-cultural content plans, due to the Wenyan-style in which TCM treatises are written. The purpose of the work is to identify the patterns of the language of these ancient texts in the context of the interpretation presented in them through the hierarchy of 'state and subjects'. The use of methodological holism made it possible to develop a new approach to the texts of traditional Chinese medicine from the standpoint of communication studies and neuropsycholinguistics. The mythologized interpretation of the concepts in the ancient treatises of TCM is associated with the signification of any health problem in the form of an expanded metaphor characterizing the problem as a violation of 'communication' in the body-'state' between 'vassals', 'individual social groups' and their 'leaders'. This positioning of the body's work through the prism of social relations provides an understanding of the interpretation of relationships in ancient Chinese society as a whole.

Traditional chinese medicine, the treatise of the yellow emperor on the inner, the canon of bian que on the inner, terminology, metaphor, verbalization of body problems, alternative communication, translation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149147504

IDR: 149147504 | УДК: 811.581’0:61 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu2.2024.6.10

Текст научной статьи Metaphorical terminology in ancient texts of traditional Chinese medicine: problems of understanding and translation

DOI:

As a universal system of communication between the inner microcosm and the outer macrocosm, traditional Chinese medicine (hereinafter – TCM) is often referred to as a mysterious ‘Chinese miracle’ [Arapu, 2021; Lagutkina, 2022; Cap-puzzo, 2022; Karabulatova et al., 2024], which represents the diversity of ideas about man and the world [Chen Kuo, Karabulatova, 2024; Dubrovin, 1991; Sun, 2020]. Also, TCM itself had been sacralized for a long time, as evidenced by the lack of a single recognized term before the twentieth century and the use of metaphorical names such as The “Art of Qi Huang” in The Treatise of the Yellow Emperor on the Inner [2022a, b], “Hanging a bottle gourd”, The “Green Bag”, The “Apricot Grove” [Chen Xue, 2023, p. 134]. It was only in 1936 that the name was officially unified as traditional Chinese medicine [Li Zhaogo, 2013]. However, according to V.S. Spirin, the abundance of euphemisms and metaphors has defined the perception and interpretation of ancient Chinese medical treatises, which are literary rather than scientific texts of Ancient China [Spirin, 2006].

The ancient Chinese treatises under study are interesting from the point of view of a specific interpretation of human psychophysiological problems by analogy with the internal structure of the state and interaction between social classes, groups and individual significant figures in it. This metaphoric expansion interprets psychophysiological processes as a kind of ‘deep’ communication in the human body.

The need for the correct use of the TCM terminology is becoming increasingly relevant due to the growing popularity of oriental medicine practices in healthcare not only in Southeast Asian countries, such as China, but also in Russia, the post-Soviet states and other countries. At the same time, it should be borne in mind that the TCM status in China and abroad may vary [Nichols, 2021; Wang, Kuzmenko, 2023]. Due to the preserved sacralization of the human body and its disorders, especially in Asian linguistic cultures, the issue of in-depth analysis of TCM texts from the standpoint of understanding its terminology related to Eastern lingua philosophy, in general, is urgent. The relevance of the research is due to the strengthening of ties between Russia and China, the spread of translated literature on traditional Chinese medicine, the growing interest in interpreting TCM outside its main field of practice, nuances and differences in the interpretation of terminological concepts and the Wenyan-style of written scientific texts in Chinese culture. Task complexity is defined by the need for detailed commentary on ancient Chinese terminology, as its semantics, due to its metaphoric nature, often remains unclear and incomprehensible without extensive theoretical research.

Materials and methods

The terminology of TCM goes back to the value code of the traditional culture of Ancient China, recorded in the Wenyan literary tradition, used in ancient scientific treatises and scholarly works on philosophy, culture, history and medicine as early as the 5th century BC, which leaves an imprint on modern understanding and postinterpretation in modern times [Kryukov, 1978; Chen Xue, 2023]. Chinese treatises use a style derived from ancient Wenyan traditions, whose figurative language is not common in everyday Chinese colloquial speech but widely used in scientific and technical writing. In the treatises under consideration, Wenyan-style terms present lexical and semantic difficulties that have to be tackled.

In this regard, we consider, first of all, such canonical texts of the TCM as The Treatise of the Yellow Emperor on the Inner (Huangdinei-Ching /

《黄帝内经》 / Huángdì Nèijīng), tentatively dated about 500 BC, known in Russia in translations by B.B. Vinogrodsky (Traktat Zheltogo imperatora..., 2022a; 2022b), as well as The Canon of Bian Que on the Inner , which appeared earlier than this work, or The Canon of Difficult questions in Medicine ( Nan-Ching / 难 经 / Nán Jīng ) under the authorship of Bian Que 扁 鹊 / BiǎN Què, which became known approximately already in 500–210 BC, published in Russia in the interpretation of D.A. Dubrovin [1991].

The research material is heterogeneous. First of all, the interest was focused on the analysis of translated texts of ancient Chinese treatises in comparison with the primary sources. The selection of the material predetermined the identification of three main groups: 1) metaphorical verbalization of the causes of pathological conditions, diseases and various body disorders; 2) mythological interpretation of taboo causal relationships in the human body by the terminological apparatus of TCM under the influence of traditional Chinese worldview; 3) mythologization of the description of correction approaches in TCM as an alternative dialogue with systems and organs understood in TCM as specific communicative systems of the body. The methodology is based on the psycholinguistic understanding of psychophysiology in the traditional culture of Chinese folk medicine, which interprets the interaction process of all systems and organs of a living organism using understandable images and the structure of ancient Chinese society. At the same time, descriptions of neural and cognitive relations provided in ancient treatises predetermined the appeal to neurobiology and neuro-linguistics to establish the content of terminological concepts. Researchers point out the philosophical, mythologized, folklore traditions of the TCM interpretation in Chinese linguoculture [Chen Xue, 2023; Slingerland, 2013; Hammer, 1999; Nichols, 2021].

The neuro-linguistic map of the human brain compiled by [Karabulatova et al., 2024a] relies on stable metaphors that are understandable in Chinese society including the Jade Emperor, also known as Yu Huang 玉皇 or Yu Di 玉帝 , is the highest god in Chinese culture and the paramount deity in the Taoist pantheon. He is the celestial supreme ruler, The Jade Emperor, and the ultimate arbiter of human destiny. From his ethereal jade palace in the sky, he exercises control over the entire universe. The heavens, earth, and netherworld all fall under his dominion. He commands a multitude of deities and spiritual beings at his behest. In addition, in Chinese mythology, it is believed that the Jade Emperor turns his attention to the visual representation of the world, phenomena, living beings, objects, so it is not surprising that his image is identified with the zone of visual representation and visual information in the brain from the point of view of TCM. The correct expression of thoughts and emotions through words are attributed to the Crystal Palace combining the Cave House and the Bright Palace. In the Chinese philosophical tradition, a complex of regulatory systems located in the brain is interpreted as the Open Crystal Palace, which includes the most vital organs of the neurohumoral system (pineal gland, thalamus, hypothalamus and pituitary gland) [Jia,Chia, Sakser, 2016].

Using neurolinguocognitive mapping [Wong, Huo, Maurer, 2024] based on the theory of regulation and the so-called dominant criteria of clinical signs, recent instrumental studies have confirmed that neural connections deteriorate due to exposure to repetitive or atypical sounds for native speakers of a particular language [Soltész, Szűcs, 2014]. Neurolinguocognitive mapping allowed researchers to find out that the interaction between the brain parts changes significantly during an illness. Using magnetic resonance imaging data, scientists created maps of functional brain networks that show semantic connections between its parts [Khorev et al., 2024]. Additionally, scientists analyzed connections in the brain at two levels: global, when they considered the general characteristics of networks and their cor- respondence to large-scale brain networks, and local, when they examined individual connections forming groups. It turned out that in case of depression and other chronic diseases in the brain, failures occur in the process of group formation. It means that functional networks are no longer clearly divided into large parts. Information is normally processed within functional groups, but illness forces the brain to use more neural connections between the parts [Khorev et al., 2024]. In [Khorev et al., 2024], using MRI, the authors illustrate deep changes in the world perception by people with anxiety and depression, which emphasizes the validity of the provisions on the violation of cognitive connections in painful conditions in the ancient treatises of TCM. Within the framework of Chinese medicine, various ailments are associated with a violation of harmony in the work of the brain as the main regulator of all body systems, which is confirmed in modern studies of norm and pathology [Khorev et al., 2024]. Thus, the treatises on TCM metaphorically describe the nervous system impact on the activity of the heart, liver and other organs.

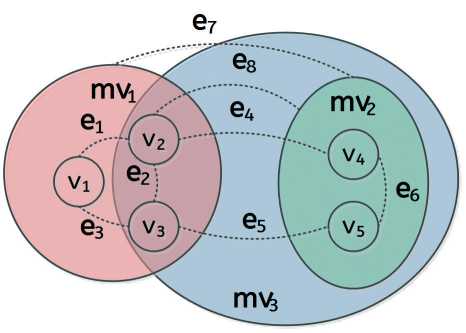

In this regard, the treatises of TCM were considered using the theory of metagraphs, which makes it possible to combine various features into a generalized system. The key advantage of using metagraphs to model the semantics of the terminological system of TCM treatises is the possibility of easily supplementing existing vertex concepts and semantic connections with additional vertex values using concepts without violating the existing semantic elements and changing the relationship between them. The imposition of different maps and the comparison of the terminological apparatus using the theory of metagraphic representation made it possible to clarify the scope of TCM concepts in the modern system of neuro-linguistics, translating the metaphorical designations of TCM terms into modern terminology. Methodological holism, due to the application of the metagraph theory [Gapanyuk et al., 2024], predetermined the use of various methods subordinated to the idea of research – the creation of a model of ‘internal communication’ of systems and organs in the interpretation of ancient texts of TCM.

A metagraphic representation model, which is a complex graphical model (see Figure), can be used to solve the technologically claimed prob- lem. In this article, the metagraph is presented as follows: MG = {V, MV, E}, where [MG] represents the metagraph, the sign [V] represents the set of vertices of the metagraph, the designation [MV] means the set of meta-vertices of the metagraph, and [E] represents the set of connections between semantic vertices [V], acting the edges of the metagraph. In this case, the vertex of the metagraph is [vi] = {mark}, [vi] = [V], and the symbol [atrk] means an attribute.

A fragment of the TCM metagraph is constructed based on the parameters MGi = {evj}, evj ∈ (V ∈ E ∈ MV), respectively, in it, the symbolic abbreviation [evj] means an element that belongs to the union of vertices, edges and metavertices. The metagraph meta-vertex is calculated according to the formula: [mvi] = ⟨ {atrk}, MGf ⟩ , mvi ∈ MV, where [mvi] is the meta-vertex of the metagraph, [atrk] is an attribute, the abbreviation MGf means a fragment of the metagraph.

Certain aspects of the ‘the body as a state / country’ concept embedded in TCM are reflected in linguistic markers that represent the communication of the body systems as a hierarchy of power and state structures through the prism of interpreting the apex and meta-apex of the metagraph, which represents the basic socio-political meaning of ‘power’. The concept of ‘the body as a state / country’ is distinguished based on constant references to the social imperial structure of ancient Chinese society. Since The Treatise of the Yellow Emperor on the Inner is the earliest fundamental source, it shows a close connection between the way of knowing the world and the holistic worldview expressed by the conceptual constructions Yin-Yang (the binary code of the existence of all living things), San Tsai (the triple union of analogies ‘heaven – human – earth’) and Wu Xing of ‘five elements’, representing such primary elements as ‘Water – Fire – Wood – Metal – Earth’. In Ancient Chinese philosophy, the human body also has three levels, which conventionally represent heaven (upper level), man (middle level) and earth (lower level) [Pushkarskaya, 2021]. Despite the philosophical nature of the concepts, the interaction of the opposite forces of Yin and Yang is shown in the chapter Su Wen / Basic questions in the context of the possibility of their application in practice, using the example of the parable of the Taoist hermits who sought the secret of eternal youth (Traktat Zheltogo imperatora..., 2022a). In the first chapter, entitled Shang gu tian zhen lun / On the Heavenly Truth of ancient times, the Yellow Emperor talks about a legend according to which in ancient times people used to be more perfect than they are now, because they possessed the macrocosmic laws of the transformation of heaven and earth, understanding the flows of Yin and Yang, controlling their breath and life force in the form of Qi energy [Krushinskiy, 2020; Wang, 2019]. The tension that arises as a result of the interaction of the opposite forces of Yin and Yang generate the life energy of Qi, which determines the period of vitality of a living organism [Wang, 2019].

A comparison of the semantic links between the terminological peaks of the concepts of TCM and the terms of neuro-linguistics allowed us to establish that the Crystal Palace of the Emperor combines the cortical and subcortical structures of the brain), the Middle (Main) The Emperor’s Palace correlates with the cardiovascular system, and

Universal high-level data metagraph architecture

Note. Source: [Gapanyuk et al., 2024].

the Yellow (Lower) Emperor’s Palace combines the pelvic organs and the reproductive system). At the same time, the very concept of 肺 [fèi] ‘lungs’ is conveyed by the metaphorical term ‘baldachin for Emperor and the five main organs’. The heart and lungs are located in the chest, where the accumulation of mixed Qi energy occurs, so this place is also referred to as the Sea of Qi. In Chinese philosophy and medicine, the body and mind are not considered a mechanism, but rather a cycle of Qi energy in various interacting manifestations that make up the body. Body and soul are just forms of Qi [Geng et al., 2016; Hsu, 2005]. The philosopher Chang Tsai, who lived in the Song Dynasty, explained that all manifested things constitute the essence of being, which is predetermined by the saturation of Qi energy [Kasoff, 1984]. In a variety of subjects and objects, this all-encompassing energy of the general Qi is transformed through the processes of interaction of the streams of Yin Qi and Yang Qi, like living and dead water. At the same time, the flow of Yin Qi forms the earth, and the flow of Yang Qi symbolizes the Sky, thanks to their combinations, there is a cycle of living and inanimate in nature [Dubrovin, 1991].

In Chinese medicine, the body and mind are treated as the result of the interaction of certain vital substances that manifest themselves in varying degrees of ‘materiality’ [Dubrovin, 1991; Fayzullin, 2019; Krushinskiy, 2020]. Some of them are very sparse, while others are completely immaterial. All these substances, according to ancient Chinese doctors, make up the continuum of the psyche and body. The philosophy of TCM defines five vital substances, namely: Qi Energy, Blood, Essence (Jing) (sexual power, fertility), Body Fluids and Shen (Mind). These concepts are of interest in terms of understanding the Chinese mentality in general. So, it is well known that the omnipresent Qi energy has been the basis of Chinese philosophy from the advent of Chinese civilization to the present (Traktat Zheltogo im-peratora..., 2022a). The character of Qi indicates something both material and immaterial [Kang, Yu, 2024]. Therefore, the very concept of Qi is translated as ‘vital energy’, ‘material force’, ‘matter’, ‘ether’, ‘vital force’, and ‘driving force’ [Krushinskiy, 2020; Wang, 2019]. The problem of the ambiguity of translation is due to the versatility of the implementation of Qi, which can manifest itself in different ways depending on the circumstances. TCM treatises use this term in two meanings: 1) pure energy produced by the body, which gives physical and mental strength; 2) functional activity of body systems and organs. The term ‘Jing’ is usually translated as ‘essence’ (Traktat Zheltogo imperatora..., 2022a; 2022b). The ‘jing’ hieroglyph includes two graphemes – ‘rice’ on the left and ‘purified’ on the right, which create the concept of ‘Essence’ as a kind of idea of something that arises in the process of purification or distillation – a purified substance that is obtained at the exit from a coarser base. This process of releasing a purified substance implies that the Essence is a precious, cherished and carefully preserved substance [Fayzullin, 2019].

The term ‘Essence’ is found in ancient Chinese medical treatises in three different meanings: 1) Pre-Heaven Essence; 2) Post-Heaven Essence; 3) the Kidney Essence. Pre-Heaven Essence is the only kind of essence of the fetus in its intrauterine development since it does not have its physiological activity. Otherwise, this type of Essence is also called Prenatal Essence, corresponding to amniotic fluid. The Pre-Heaven Essence determines the basic forces of human development. Post-Heaven Essence is a common type of various essences produced during eating, it turns on immediately after birth and accompanies a person throughout his life [Fayzullin, 2019; Li et al., 2022].

This metagraph model allows you to create alternative ways of organizing complex markers using a meta-vertex based on the same set of simple markers (see Figure). This metagraph model is designed to describe complex data structures, which include terminological concepts of TCM, which include philosophical explanation, subjectfunctional interpretation, objective information and associative references to other concepts of the linguistic and cultural plan. The presented fragment of the universal high-level metagraph model includes three meta-vertices: mw1, mw2 and mw3. The vertex v1 contains not only the vertices v1, v2 and v3 but also the edges e1, e2 and e3 that connect them, which at the verbal level is expressed by defining semantic links between the terminological concepts of TCM based on analog-the featured specifications. In addition, the metavertex v2, implying a polysemic terminological concept, includes vertices v4 and v5 based on the characteristics of the semantic connection method expressed by the edge e6 connecting them.

The designation of semantic links in the structure of the terminological concept of TCM in the form of edges e4, e5 can demonstrate the connection between individual meanings within one polysemous concept and between different concepts. These semantic links connect the semantic vertices v2-v4 and v3-v5, respectively. In turn, they form a polysemic space of the metaphorical term of TCM, designated as mv1 and mv2, belonging to different meta-vertex. The edge e7, in turn, shows the routing between the mega-vertices mv1 and mv2 of the meta-vertex. The edge e8 indicates the direction of formation of a semantic connection that connects vertex v2 and meta-vertex v2. Moreover, the hierarchical organization of the mp3 meta-vertex includes in its structure the meta-vertex v2, vertices v2, v3 and edge e2 from the meta-vertex mv1, as well as edges e4, e5, e8. Based on this, meta-vertex implements the principle of the appearance of such complex structures as ‘an organism as a state’ in data structures.

In TCM, kidneys are a symbol of power as the body’s strength (Traktat Zheltogo im-peratora..., 2022a). Recent studies by neuropsychophysiologists have found that information is stored not only in the brain but also in the kidneys. American researchers have proven that human kidney cells are able to collect and store information like neurons in the brain [Kukushkin et al., 2024].

In Chinese philosophy and medicine, the body and mind are considered not as a mechanism, even if complex, but rather as a cycle of Qi energy in various interacting manifestations that make up the body. Body and soul are viewed as forms of Qi , which is the basis of everything, and all other vital substances are manifestations of Qi of varying degrees of materiality, from completely material (for example, body fluids) to completely immaterial (for example, mind – Shen). Shen has both narrow and broad meanings. In a narrow sense, Shen is understood as human will, thought. In a broad sense, Shen is the main spiritual force of a person, controlling his life activity and external reflection, that is, consciousness. This also includes gaze, facial expressions, temperament and other aspects.

In the philosophy of TCM, the reproductive systems of men and women comprise Pre-Heaven Essence, which is closely related to the Fire of the Gate of Life (the term ‘Ming-Men’ has no equiva- lent in classical medicine). This Fire of the Gate of Life is located between the kidneys, producing physiological Fire of the whole organism, which is an absolutely necessary condition for ensuring the normal activity of the physiology of a living being. It is believed that the Fire of the Gates of Life accompanies any living being, starting from the moment of conception. In addition, the concept of Pre-Heaven Essence characterizes the vitality of a living organism also from the very conception, but it transforms after birth, ‘growing’ to Kidney Essence during puberty. This is an important milestone when the Kidney Essence generates menstrual blood and an egg in women and sperm in men. Thus, the traditional Chinese worldview interprets the Fire of the Gate of Life as the realization of Yang energy Before-Heaven Essence. At the same time, Pre-Heaven Essence represents Yin energy. Despite the metaphorical and metaphysical meaning of the concept of Ming Meng, ancient Chinese medical treatises determine the location of this Fire of the Gate of Life at a specific point in the lumbar spine. Localization of Pre-Heaven Essence is concentrated at a point associated with the location of the uterus in women and the scrotum (Sperm Room) for men. Accordingly, the Gate of Life itself is the residence of the Mind.

In TCM, from the point of view of the structure of ensuring the vitality of the body, the Kidney concept correlates with the concepts of ‘well of life’, ‘root of life’, ‘source of vitality’. Based on the architecture proposed in the described above metagraph model, the kidneys as a source of vitality are associated with the work of the Crystal Palace, the Main Palace and the Lower Palace. The symbolic meaning of the Kidney concept as a ‘source of vitality’ in its relationship with other systems and organs is emphasized by the protection of the ‘source of strength’ by the great commander, commander-in-chief of the troops ‘liver’. At the head of the hierarchy is the Emperor – ‘heart’, who lives in the Main Palace and can visit the Crystal Palace (compare: ‘the heart is pounding in the temples’), as well as go down to the Lower Palace (compare: ‘the heart went down’). In understanding disease management, the concept of spirits is interesting, which may be the root cause of the disease. According to Chinese legend, once upon a time, a rich man’s wife and daughter fell ill. The doctor who was called claimed that two warriors with spears were buried in a corner of the house. One bullet hit the heart, causing the wife and daughter to experience heart pain, and the other hit the head, which led to headaches. The skeletons of the soldiers were discovered, and the disease receded. Accordingly, the subtle organization of the body’s settings perceived them as enemies to physical and mental health.

These models reflect an understanding of the psycholinguistic aspects of neurodegenera-tive processes in traditional folk medicine. For example, the concept of ‘stupidity’ is literally represented by the phrase ‘brain problems’, which means both a state of mind and a stupid act ( 你脑子有问题吗? / nǐ nǎozi yǒu wèntí ma? / Do you have a problem with your brain? ); a child with hydrocephalus is a ‘doll with a big head’. Euphemisms related to human psychophysiological characteristics are considered in detail in the study by Yuan Liying and Huang Yaxin [2023]. The philosophy of TCM is primarily a culture of balance of power, therefore, a bias towards both excessive manifestation of negative emotions and positive emotions is assessed as a destructive factor of health.

Neurodegenerative processes are described in TCM treatises through concepts such as ‘fullness’ and ‘emptiness’, which can be found in the text of Chuang Tzu. Therefore, there are such models as Emptiness of the Kidney energy channel, Emptiness of the Lower Palace. In addition, such models interpret the humoral-vegetative genesis through the concepts of ‘heat’ and ‘cold’, for example, ‘fever of the stomach’, ‘cold of the kidneys’. These ideas can be found in the works of Hongxu and other authors [2023]. These models consider neuro-immunological conflicts in psychosomatics, as a result of which representatives of TCM point to the danger of excessive expression of emotions not only in the negative spectrum, but also in the positive, believing that they provoke ‘external’ and ‘internal’ damage [Ji et al., 2016]. The parametrizing components in these models are extralinguistic markers of structural deficiency, which enter into binary opposition with primary regulatory deficiency in the context of the yin – yang dialogue [Fu et al., 2021; Qin, Chen, 2004].

In TCM, the diagnosis considers the functional activity of the body systems and internal organs, in this regard, the names of some diseases require a long explanation for representatives of Western culture (for example, such as Emptiness and Weakness of the Yang Kidneys, as well as Emptiness of the Yin Kidneys). Thus, the well-known pulse diagnostics is associated with measuring the emperor’s strength, according to which various types of pulse are distinguished based on the dichotomy of Yin and Yang energies. For example, a rapid pulse is of the Yang type, and a slow pulse is of the Yin energy. The characteristic of the pulse depends on the work of the heart, which in traditional Chinese medicine has its own consciousness. In addition, metaphors and euphemisms are used to describe bodily problems in traditional Chinese medicine, which are characteristic of describing a variety of problems: Emptiness of the Yin of the Kidneys ‘poisoning with medical drugs’; lack of strength of the Qi of the Kidneys ‘enuresis’; bean-shaped pulse ‘rapid pulse’; diseases of demons ‘viral diseases.’ In the process of translation, there is often a problem of conveying the meaning of terms related to the philosophical concepts that underlie TCM. In some terms, key concepts such as Tao (the Way), Yin (the dark beginning) and Yang (the light beginning) can be used. It may be difficult or even impossible to find an exact equivalent for such terms in another language. In such cases, transliteration with the addition of explanations is often used. However, this approach may affect the quality of the translation. For example, in one of his articles, S.A. Komissarov gives an example of a distortion of the term gōngfu / 功夫, which is often translated as ‘kung fu’ or ‘gung fu’. But ‘kung fu’ is not only martial arts, but also all aspects of human physical and spiritual activity. This can be understood if you consider that one of the translation options is ‘skill’. In the context of pop culture, where this term is most often found, this is not particularly dangerous [Komissarov, 2009]. However, in an area directly related to human health, terminological errors can cause serious problems. Other challenges arise because some of the terms can be associated with the names of internal organs, such as sānjiāo / 三焦 , liùfǔ / 六腑, zàngfǔ / 脏 腑, jīngluò / 经络 and others. Unlike the terms associated with the philosophical basis of traditional Chinese medicine, these names reflect Chinese ideas about the structure of the human body and the processes occurring in the body, which differ from those accepted in Western medicine. The main problem is that there is no single translation option for these terms. The variants may be synonymous, but have different shades of meaning. For example, translations for jīngluò in Russian are ‘meridians’, ‘channels’ and ‘channels and collateral vessels’ in English [Kuo, Karabulatova, 2024]. This can have an impact on the perception of unusual ideas and on the subsequent awareness of the key provisions of TCM since the same phenomenon is viewed from completely different angles. In the names of diseases, floral components usually do not have a direct relationship to the essence of the disease. For example, the name lily disease contains the component ‘lily’ (合), which in the past was used to treat this disease. In most cases, the floral components in the names of diseases contain a metaphor. For example, plum stone qi ‘lump in the throat’; the inverted flower ‘hemorrhoids with node prolapse’.

However, modern research in the field of medical ethics indicates that the use of euphemisms in health terminology results in a blurred understanding of the specifics of diseases, devaluation of health problems and confusion of symptoms [Kalinin, 2021; Karabulatova et al., 2024b; Peterson, 2021; Jia et al., 2021]. This technique is also considered as manipulation, which negatively affects the perception of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the public consciousness outside China [Khabarov, 2021; Solodun, 2024].

Within the framework of a cognitive-discursive analysis, the evaluation of metaphors and euphemisms in ancient Chinese medical writings is grounded in an appreciation of the discursive nature of metaphorical terminological definitions [Boey-naems, et al., 2017; Kövecses, 2018; Zinken, Hell-sten, Nerlich, 2008], as well as the inherent meta-phoricality of the discourse of traditional Chinese medicine itself [Baranov, 2014; Kalinin, 2021].

The analysis of the TCM texts takes into account the general system of knowledge and theoretical foundations that have developed in Chinese culture, guided by the fundamental concepts of simple materialism and spontaneous dialectics.

Results and discussion

Over the long centuries of its existence, traditional Chinese medicine has developed a num- ber of fundamental principles that have become its hallmark. Among them, one can single out the Taoist concept of life, which considers health as a harmonious combination of physical and spiritual principles, a holistic and balanced approach to thinking, as well as verbal methods of diagnosis and treatment based on evidence-based medicine. In addition, an integral part of Chinese medicine is the ethical principle of sincerity of a doctor who must take care not only of the body but also of the soul of his patient. It is crucial to recognize that we are dealing with a secondary interpretation of neuropsychological communication signals within a specific ethnolinguistic culture, which interacts with the interpretive principles inherent in another system of linguistic and semiotic coordinates.

In our opinion, the universal approach to animalism in the Chinese folklore and mythological worldview has developed a common point of view on the supernatural causes of diseases that are provoked by certain evil entities or demon spirits that have invaded the subtle structure of the body, which it signals in the form of symptoms of the disease [Karabulatova et al., 2021; 2023; 2024a; 2024b; Tychinskikh, Zinnatullina, 2022].

At the same time, almost every region of China has developed its own TCM school with a unique methodology, which made it possible to talk about over 300 scientific TCM schools in China. Accordingly, each school has developed its own terminological glossary, which records regional interpretations of TCM treatises. There are special studies on regional branches of TCM that have appeared in other countries, which reflect a different understanding of the world and interpretation of metaphoric terms in TCM when they are borrowed from other cultures [Naghiza-deh et al., 2019].

It was believed that ancient Chinese doctors had supernatural abilities, as they practised meditation, immortality cultivation, healing, and body rejuvenation as part of the art of healing. Due to the transmission of the Tao of immortality, texts from Chinese folklore reflect the so-called art of healing. At the same time, the ban on the use of direct designations of body parts, health problems and treatment methods caused the creation of an expanded symbolic space of the human body as a kind of allegorical text in the coordinates of the struggle between Good and Evil, Life and

Death, Disease and Health, in which at the level of psychophysiology, all manifestations of the human body are seen as alternative non-verbalpara-verbal communication.

Meanwhile, Russian textbooks often use the terminology of TCM without any historical, philosophical, or linguistic-cultural explanations, which creates additional difficulties for those who seek to study TCM outside its historical and cultural context [Dubrovin, 1991; Ovechkin, 1991; Popovkina, 2022]. Analyzing the oriental medical practices common in Tibet and mainland China, Fayzullin identified a clear division of TCM texts into theoretical and practical texts [Fayzullin, 2019], which displays a cardinal difference between the principles of the sacred ritual discourse of healing and Russian traditional medicine [Kirilenko, 2016]. The researchers also stress the importance of the philosophical and religious components because Tibetan traditional medicine is based on the Buddhist philosophy of the five elements (fire, earth, water, air, ether). In addition, translated literature uses literal translation, distorting the understanding of the TCM methodology.

In parallel with the spoken Chinese language, Wenyan, the old literary language having a centuries-old tradition, existed and developed, maintaining a distinct distance in terms of usage, which necessitated the creation of translation dictionaries in the Chinese language itself within its own linguistic culture to carry out a possible reconstruction and modeling of the terminology of Chinese medicine [Ovechkin, 1991]. We will give an example of the concept of ‘buttocks’ denoted so far in Chinese by the euphemism ‘chrysanthemums’. At the same time, to designate the same concept, the Wenyan language uses the euphemism the Lower Gate of Immortality. Also, the concept of ‘uterus’ is colloquially conveyed through the euphemism of ‘Son’s Palace’, and in the Wenyan-style – The Lower Ocean of Immortality.

The texts of TCM are characterized by a functional and pragmatic approach to interpreting a variety of signal-sign ways of the body communication with humans and the world around them.

Medical and philosophical translations of ancient Chinese works use poetic and figurative language, which puts TCM texts in a special position. Any TCM treatise begins with a description of Chinese philosophy, which forms the basis for diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention of various ailments. In addition, The Treatise on the Inner often illustrates a particular disease with parables, stories, and observations of natural phenomena, linking together three planes of manifestation (heaven-human-earth). Since these texts appeal to Eastern philosophy, the poetics of terminological names and metaphors used to describe symptoms and psychophysiological states of a person are clearly determined by this philosophy. For example, the root cause of diseases is determined by the intemperance of emotions and the dominance of such psycho-emotional states as passion and anger. In addition, ‘stupidity’ is indicated as a state of mind that also causes an illness in humans.

Metaphorical explanations are used in the recipes of special potions containing certain herbs and minerals. For example, cinnabar, which has played an important role in Chinese culture since ancient times, was used not only in art but also in funeral rituals, traditional medical practices and alchemical recipes. In traditional Chinese medicine, cinnabar refers to the concept of ‘internal alchemy’, which is responsible for the origin and development of life. Therefore, the conception and development of a child are determined by the ‘heavenly methods of primordial cinnabar’ (Tian Yuan dan fa) or ‘human methods of primordial cinnabar’ (Ren Yuan dan fa). The development of methods of ‘internal’ alchemy, such as complex mixtures of TCM, revealed three treasures of the fundamental principle of the human matrix: the formative principle – Jing, energy – Qi and spiritual – Shen. Usually, these medications are called herbal preparations, which is not entirely true since besides herbs, it may contain components of animal origin and mineral powders and suspensions, which formed the basis for the creation of a medicine (yaou 药物 ) from which alchemical cinnabar tribute was obtained in the human body. This substance is also known by other names: ‘great cinnabar’ (dadan 大丹 ), ‘Perfectly Wise Embryo’ ( shengtai 圣胎 ), ‘Dao Embryo’ ( daotai 道 ), ‘the newborn’ ( yiner 婴儿 ), etc. The exotic components of TCM medicines include ‘dragon bones’ (‘large bones that have been buried for at least 30 years’), ‘dragon tears’ (‘rock crystal’), and ‘jade objects in the shape of tigers’ (‘natural amber’).

Simultaneously, the prolonged seclusion of Chinese society from external influences contribut- ed to a certain detachment in the education of Western practitioners in TCM techniques. Moreover, the misinterpretation of the Chinese philosophical perspective embedded in TCM fostered a tendency towards mythological interpretations of terms, leading to the perception that translating TCM concepts is not only impractical but also inadequate [Moran, 2005]. In this regard, when translating, it is necessary to apply explanations from the field of medicine. For example, the term Upper Gate of Life refers to the trigger zone in the scapula area, the place of attachment of several muscle groups, thanks to which a person does not hunch over and does not slouch. The weakening of the Upper Gate of Life leads to the so-called ‘supplicant pose’ or ‘question mark’, which in popular culture is described figuratively as ‘he was bent by the burden of life’. At the same time, the Lower Gate of life is opposed to the Upper Gate, respectively, they are located in the lower part of the body. The localization of the Lower Gate of Life is anatomically defined as the place of exit of the sciatic nerve in the gluteus maximus. The weakness of the Lower Gate leads to a shuffling senile gait. The euphemistic term Heartbeat source means ‘cardiovascular system’. The entire space of the pelvis and hypochondrium is designated as the Bloody Sea, and this is not accidental, because a wound to the abdomen is fatal.

In general, it can be stated that the interpretation of metaphorical terms in the texts of traditional Chinese medicine presents significant difficulties both within the framework of Chinese linguistic culture itself and in translated versions of TCM texts beyond its borders. Semantic analysis of terminology in TCM is of key importance for understanding the classification parameters of information exchange at the level of ‘body language’ signals and identifying problems of ambiguous interpretation of semantic terminological expressions in TCM, taking into account the linguistic and cultural characteristics associated with TCM.

The analysis of metaphorical euphemisms used as terms in TCM allows them to be divided into two large groups, each reflecting different lexical and semantic associations inherent in Chinese linguistic culture. Table presents the thematic distribution of metaphorical names in the TCM texts.

In traditional Chinese culture, metaphors and euphemisms are used to describe taboo topics [Lagutkina, Karabulatova, 2021]. In TCM, the poetic name ‘lily disease’ ( bǎihébìng 百合病 ) designates a major depressive disorder, or otherwise depression [Shang et al., 2020]. This metaphor is related to the fact that depression has many ‘buds’ – the causes of this disease. At the same time, ancient Chinese treatises define depression as a disease of the heart and lungs, which are severely damaged, so a state of depression arises. In addition, the scent of lilies is strong, depressing and irritating. These observations made it possible to designate depression as a disease of lilies in TCM.

Wenyan stylistics reinforces the tendency to use metaphors as terms, so the female cycle, controlled by the Moon, is interpreted in the context of Eastern metaphysics. In this regard, the metaphorical euphemism ‘blinding moonlight’ is used as the name of menstruation in ancient Chinese treatises on TCM, emphasizing the dominant influence of the lunar cycle on the regulation of the female hormonal system [Karabulatova et al., 2024b].

Special attention should be paid to terms containing a coloristic component. It should be emphasized that colors are also analyzed from the point of view of the fivefold model of the world structure, therefore it is important to understand the linguosemiotic meaning of color in the context of terminological names of diseases in TCM.

In most cases, color-indicating components have a literal meaning, indicating the color of the skin, mucous membranes or secretions in certain

Euphemia markers in ancient TCM texts

|

Methods of euphemism in TCM texts |

Data for TCM texts |

|

|

Number of units |

A specific example |

|

|

Accentuation of logical relationships based on cause and effect |

238 |

The blinding light of the Moon; The fields of cinnabar production; the period of the Wind; Hanging a jug to help the world |

|

Expression of definitions in the form of comparisons |

562 |

The Abode of Mystery; The Sea of Breath; After the Heavenly condition; wonderful canal; Fire toxin; Liver fever; Green Bag; Yellow Courtyard Path; Dragon Gate; Jade Cushion; Yellow River; Wind Palace; Central Yellow Palace; Blooming Pond |

diseases. However, in the case of the term ‘green blindness’ 青盲 ‘glaucoma’, the word 青 ‘green’ is used figuratively. Despite the fact that with glaucoma, the eye does not change its color, and the eyesore does not have a certain shade, in this context, the word acquires a metaphorical meaning.

In the Chinese linguistic worldview, the lower abdominal region is regarded as sacred, symbolizing longevity and, potentially, immortality. This meaning is actualized with the help of such euphemisms as the Central Yellow Palace, which emphasize the central role of the neurohumoral system in maintaining vitality and prolonging life (Traktat Zheltogo imperatora..., 2022b). The emphasis on this region is further accentuated by the use of terms like ‘central’ and ‘yellow,’ where ‘central’ implies the paramount importance of pelvic organs for reproductive and vital functions, while ‘yellow’ evokes connotations of imperial power in ancient Chinese culture, imbuing this concept with an additional layer of symbolic significance.

It is no mere coincidence that Peihua Wu draws attention to this particular coloronymic metaphor of yellow in Chinese linguistic culture [Wu, 2018]. Simultaneously, the yellow color is associated with a proto-categorical archetypal interpretation of the symbol of the sun, which in turn is linked to ideas of satiety and abundance. However, in Chinese traditional culture, the sun can also be used in a medical sense as a definition of a decease symptom. For example, ‘redness of the face’, ‘red face’ is transmitted as a metaphor for ‘wearing the sun’, formed from a combination of the verb 戴阳 ‘to wear (accessory)’ and the noun ‘sun’. The metaphor rests on the observation that the skin burns in the sun, so it turns red.

The term 白喉 ‘white larynx’ indicates the main symptom – the presence of a white purulent plaque on the walls of the larynx in diphtheria, therefore diphtheria is designated as a metaphor for ‘white larynx’. It is noteworthy that in the treatises of traditional Chinese medicine, the red color is not used in the names of diseases. However, the red color can be transmitted indirectly, through other hieroglyphs. For example, the term 赤丝 chìsī qiúmài ‘redness of the conjunctiva of the eyeball’ can be divided into three components: ‘subconjunctival capillaries’, ‘dragon-shaped, writhing’ and ‘artery’. The word 赤丝 can be translated as ‘scarlet’, and 丝 as ‘thread’. Thus, the red color of the capillaries is transmitted through the word 赤 (scarlet).

However, the implicitness of the coloronym-ic nomination in the terminology of TCM, which is understandable to native speakers of Chinese, causes cognitive dissonance [Bulegenova et al., 2023] in native speakers of Russian when the perceived text develops the emoticeme of nega-tivization [Karabulatova et al., 2023].

In linguosemiotics related to the sacred aspects of the human body, the Central Imperial Palace represents the forbidden lower abdomen. However, the emperor himself is outside this palace, because in traditional Chinese medicine, the Emperor of Health is associated with the Heart (Traktat Zheltogo imperatora o vnutrennem, 2022a). Based on this, the work of the entire living organism refers us to ancient mythologems extracted from legends, which describe a mysterious world where people, nature, gods and spirits depend on each other, but at the same time are in constant communication with each other (such as The Upper Gate of Immortality; The Celestial state; Demon’s Breath; Lake of Mystery). This approach to the interpretation of ‘body language’ allowed TCM treatises to convey the relationship between different worlds (gods, humans, demons, animals, plants, earth – stars, people of the underworld, etc.) through the use of metaphors that act as ethno-cultural triggers of psychosomatic communication. Further, it illustrates the vitality of metaphorical perception of reality not only in antiquity but also in modern Chinese society, which can be reflected by mapping mythological images to specific systems in the human body.

Conclusion

Ancient ideas about traditional Chinese medicine continue to amaze modern people, and methods for evaluating its effectiveness are being actively developed within the field of digital humanities. Metaphorical terminology in ancient texts on Chinese medicine can be attributed to differences in worldview approaches towards the causes of disease, which led to the sacralization of this knowledge and the formation of a unique style known as Wenyan, the quintessential Chinese metaphor found in TCM. The Chinese tradition of diagnosis and treatment relies on knowledge of body anatomy and an understanding of the relationships between individual systems and organs. This knowledge has only recently been confirmed through the use of instrumental techniques and artificial intelligence. The sacred and mythological nature of the metaphorical concepts and terms in TCM is linked to the philosophical concepts of Buddhism and Taoism, which aim to achieve balance and harmony. This gives reason to believe that TCM interprets all psychophysiological processes through the lens of finding harmony within a person. These concepts have been passed down through oral folklore, and in the Chinese tradition, they had a more practical application, based on ideas about anatomy.

TCM originated from magical practices, but unlike Russian traditional medicine, it continued to develop as a medical practice. Religious beliefs also influenced the development of TCM, and the ancient beliefs of shamanic Taoism became the basis for the techniques used in traditional Chinese medicine. This has influenced the attitude of the Chinese towards health and various diseases.

Currently, there is no well-established terminology of TCM in Russian linguistics, which makes research in this area especially relevant. The terminological tradition in China has an ancient history and has had a significant impact on the formation of modern terms. However, terminology as a branch of Chinese linguistics began to develop relatively recently.

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the concept of disease has a different understanding than in the Russian mind, and the attitude towards medicine in general is different.

The ideas related to the early periods of Taoism development require the translator of the terminology of traditional Chinese medicine not only to have a deep understanding of medical aspects but also deep knowledge in the field of Chinese culture and philosophy, which influenced the formation of a special system of traditional Chinese medicine, its ideas about the processes occurring in the human body and their relationship with the outside world.

In TCM, there are a number of problems related to both the philosophical and religious basis and the peculiarities of the Chinese language. One of the key elements influencing the formation of metaphorical definitions of diseases is the coloronym, which is reflected in the fivefold model of the world. The coloronym is also present in the terminological names of diseases, although it does not always indicate the manifestation of certain symptoms directly.

The binary nature of the TCM system in Yin-Yang coordinates opens up opportunities for formalization and reduction to a single terminological standard. The Wenyan-style, which is actively used in the terminology of TCM, is based on the expansion of semantic meaning through metaphor.

At the same time, TCM is characterized by the use of familiar concepts in a figurative sense, as shown by the example of the concepts of heart and kidneys . The complex system of interaction between systems and organs is illustrated using a metagraphic representation, which allows us to detect the semantic connections that led to the appearance of a particular meaning.

NOTE

1 The article was prepared with the support of the priority grants of the Social Sciences Foundation of the People’s Republic of China No. 17CYY057 and No. 208ZD312. The key topic of the educational program of Heilongjiang Province No. GJB1320258.

Список литературы Metaphorical terminology in ancient texts of traditional Chinese medicine: problems of understanding and translation

- Arapu V., 2021. Bats and Diseases in the Context of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic and Magic Medicine Practices: Perceptions, Prejudices and Realities (Historical, Zoological, Epidemiological and Ethnocultural Interferences). Journal of Ethnology and Culturology. DOI:10.52603/rec.2021.29.01

- Baranov A.N., 2014. Deskriptornaya teoriya metafory [Descriptor Theory of Metaphor]. Moscow, Yaz. slav. kultury Publ. 632 p.

- Boeynaems A., Burgers Ch., Konijn E., Steen G., 2017. The Effects of Metaphorical Framing on Political Persuasion: A Systematic Literature Review. Metaphor and Symbol, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 118-134. DOI:10.1080/10926488.2017.1297623

- Bulegenova I.B., Karabulatova I.S., Kenzhetayeva G.K., Beysembaeva G.Z., Shakaman Y.B., 2023. Negativizing Emotive Coloronyms: A Kazakhstan-US Ethno-Psycholinguistic Comparison. Amazonia Investiga, vol. 12, no. 67, pp. 265-282. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2023.67.07.24

- Cappuzzo B., 2022. Intercultural Aspects of Specialized Translation. The Language of Traditional Chinese Medicine in a Globalized Context. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, vol. 18, no. 5, https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2022.v18n5p25

- Chen Xue, 2023. Translation of Terminology of Traditional Chinese Medicine into Russian: Cultural Communication and Translation Features. Nauchnyi dialog, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 123-140. DOI:10.24224/2227-1295-2023-12-10-123-140

- Chen Kuo, Karabulatova I.S., 2024. The Concept of “Traditional Chinese Medicine” in Modern Media Texts About the Treatment of COVID-19 in Russian and Chinese. Zhurnal Belorusskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Zhurnalistika [Journal of the Belarusian State University. Journalism], no. 2, pp. 63-67.

- Dubrovin D.A., 1991. Trudnye voprosy klassicheskoy kitaiskoy meditsiny: Traktat Nan-Tszin [Difficult Questions of Classical Chinese Medicine: Nanjing Treatise]. Leningrad, ASTA-Press. 223 p. Fayzullin A.F., 2019. Filosofiya tibetskoy meditsiny [Philosophy of Tibetan Medicine]. Ufa, Bashkir. gos. un-t. 211 p.

- Fu R., Li J., Yu H., Zhang Y., Xu Z., Martin C., 2021. The Yin and Yang of traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Medicinal Research Reviews, vol. 41, iss. 6, pp. 3182-3200. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/med.21793

- Gapanyuk Y., Cai C., Jia C., Karabulatova I., 2024. Using Metagraph Approach for Building an Architecture of the Terminology Integration System. Kryzhanovsky B., Dunin-Barkowski W., Redko V., Tiumentsev Y., Yudin D., eds. Advances in Neural Computation, Machine Learning, and Cognitive Research, VIII. NI 2024. Cham, Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-73691-9_49

- Geng Y., Wang W., Zhang J., Bi S., Li H., Lin M., 2016. Effects of Traditional Chinese Medicine Herbs for Tonifying Qi and Kidney, and Replenishing Spleen on Intermittent Asthma in Children Aged 2 to 5 Years Old. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 32-38. DOI: 10.1016/s0254-6272(16)30005-x

- Hammer L.I., 1999. The Paradox of the Unity and Duality of the Kidneys According to Chinese Medicine: Kidney Essence, Yin, Yang, Qi, the Mingmen-Their Origins, Relationships, Functions and Manifestations. Am J Acupunct, vol. 27 (3-4), pp. 179-199.

- Hongxu L., Guangyao Z., Yongqiang L., Wei B., Yanxiong W., 2023. Clinical Retrospective Analysis of Cold and Heat Diagnosis of Traditional Chinese Medicine by Application of Infrared Thermal Imaging Technology. International Journal of Chinese Medicine, vol. 7, iss. 1, pp. 1-9. DOI: 10.11648/j.ijcm.20230701.11

- Hsu E., 2005. Tactility and the Body in Early Chinese Medicine. Science in Context, vol. 18 (1), pp. 7-34. Ji W., Zhang Y., Wang X., Zhou Y., 2016. Latent Semantic Diagnosis in Traditional Chinese Medicine. World Wide Web, vol. 20, pp. 1071-1087. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-017-0443-3

- Jia M., Chia M., Sakser D., 2016. Emotsionalnoe zdorivje: transformatsiia negativnykh emotsii v zhiznennuiu silu: rukovodstvo na kazhdyi den [Emotional Health: Transformation of Negative Emotions into Vitality: Guide for Every Day]. Moscow, Sofia Publ. 221 p.

- Jia Q., Zhang D., Yang S., Xia C., Shi Y., Tao H., Xu C., Luo X., Zhang D., Ma Y., Xie Y., 2021. Traditional Chinese Medicine Symptom Normalization Approach Leveraging Hierarchical Semantic Information and Text Matching with Attention Mechanism. J Biomed Inform, vol. 116. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103718

- Kalinin O.I., 2021. Kognitivnaya metafora i diskurs: napravleniya i metody sovremennykh issledovaniy [Cognitive Metaphor and Discourse: Research Methods and Paradigms]. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 2. Yazykoznanie [Science Journal of Volgograd State University. Linguistics], vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 108-121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15688/ jvolsu2.2021.5.9

- Kang Z., Yu Y., 2024. Research Progress on the Application of Chinese Herbal Medicine in Anal Fistula Surgery. Am J Transl Res, Aug. 15, no. 16 (8), pp. 3519-3533. DOI: 10.62347/DZHK5180

- Karabulatova I.S., Lagutkina M.D., Amiridou S., 2021. The Mythologeme “Coronavirus” in the Modern Mass Media News in Europe and Asia. Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 558-567. Doi: 10.17516/1997-1370-0742

- Karabulatova I.S., Anumyan K.S., Korovina S.G., Krivenko G.A., 2023. Emoticeme SURPRISE in the News Discourse of Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan and China. RUDN Journal of Language Studies, Semiotics and Semantics, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 818-840. DOI: 10.22363/2313-2299-2023-14-3-818-840

- Karabulatova I.S., Ko Ch., Sun Ts., Ivanova-Yakushko M.M., 2024a. Metaphorical Euphemization of Neuropsychophysiological Communication in the Terminology of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Voprosy sovremennoy lingvistiki [Issues of Modern Linguistics], no. 1, pp. 33-51. DOI: 10.18384/2949-5075-2024-1-33-51

- Karabulatova I., Qiuhua Sun, Chao Sun, Ivanova- Yakushko M., 2024b. Problema interpretatsii metaforicheskikh evfemizmov v perevodnykh tekstakh traditsionnoy kitayskoy meditsiny (TKM) [Interpreting Metaphorical Euphemisms in Translated Texts of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)]. Filologia i kultura [Philology and Culture], no. 3, pp. 40-52. DOI:10.26907/2782-4756-2024-77-3-40-52

- Khabarov A.A., 2021. Tekhniki lingvokognitivnogo manipulirovaniya v realiyakh informatsionnopsikhologicheskogo protivoborstva [Techniques of Linguistic Cognitive Manipulation in the Information and Psychological Confrontation Environment]. Aktualnye problemy filologii i pedagogicheskoy lingvistiki [Current Issues in Philology and Pedagogical Linguistics], no. 4, pp. 72-82. DOI: 10.29025/2079-6021-2021-4-72-82

- Khorev V.S., Kurkin S.A., Zlateva G., Paunova R., Kandilarova S., Maes M., Stoyanov D., Hramov A.E., 2024. Disruptions in Segregation Mechanisms in fMRI-Based Brain Functional Network Predict the Major Depressive Disorder Condition. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, vol. 188, art. 115566. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2024.115566

- Kirilenko E.I., 2016. Bolezn i chelovek: kulturnye arkhetipy meditsinskogo opyta russkikh [Disease and Man: Cultural Archetypes of Russian Medical Experience]. Penzenskiy psikhologicheskiy vestnik [Penza Psychological Bulletin], no. 2, pp. 2-13. DOI: 10.17689/psy-2016.2.1

- Komissarov S.A., 2009. Ocherki po istorii i teorii traditsionnoy kitayskoy meditsiny [Essays on the History and Theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine]. Novosibisk, NSU. 139 p.

- Kövecses Z., 2018. Metaphor in Media Language and Cognition: A Perspective from Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Lege Artis, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 124-141. DOI: 10.2478/lart-2018-0004 ISSN 2453-8035

- Kasoff I.E., 1984. The Thoughts of Chang Tsai (1020–1077). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 209 p.

- Krushinskiy A.A., 2020. Subyekt, prostranstvo, vremya: kak chitat drevnekitaiskii tekst [Subject, Space, Time: How to Read Ancient Chinese Text]. Idei i idealy = Ideas and Ideals, vol. 12, iss. 3-1, pp. 17-35. DOI: 10.17212/2075-0862-2020-12.3.1-17-35

- Kryukov M.V., 1978. Huan Ch-In. Drevnekitayskiy yazyk: teksty, grammatika, leksicheskiy kommentariy [Huang Shu-Ying. Ancient Chinese Language: Texts, Grammar, Lexical Commentary]. Moscow, Glavnaia redaktsia Vost. lit. 502 p.

- Kukushkin N.V., Carney R.E., Tabassum T., Carew T.J., 2024. The Massed-Spaced Learning Effect in Non-Neural Human Cells. Nature Communications, vol. 15, art. 9635. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53922-x

- Lagutkina M.D., 2022. Yazykovye sposoby reprezentatsii Kitaya v rossiyskom i kitayskom mediadiskursakh v kontekste «myagkoy sily»: avtoref. diss. … kand. filol. nauk [Linguistic Ways of Representing Russia and China in Russian and Chinese Media Discourse in the Context of ‟Soft Power”. Cand. philol. sci. abs. diss.]. Moscow. 23 p.

- Lagutkina M.D., Karabulatova I.S., 2021. Evfemizmy v sovremennom manipuliativnom diskurse SMI [Euphemisms in Modern Manipulative Media Discourse]. Vestnik Mariyskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Vestnik of the Mari State University], vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 454-463. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30914/2072-6783-2021-15-4-454-463

- Li Y., Yan M.Y., Chen Q.C., Xie Y.Y., Li C.Y., Han F.J., 2022. Current Research on Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the Treatment of Premature Ovarian Failure: An Update Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, Jun 23, art. 2574438. DOI: 10.1155/2022/2574438

- Li Zhaogo, 2013. International Standardization of Terms and Terminology of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Contradictions and Debates. Principles of Translation into English of the Norms of Terminology of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Their Application. Research of Terminological Norms of the Main Disciplines of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing. 119 p. (In Chinese).

- Moran Zh.S. de, 2005. Kitayskaya akupunktura. Klassifitsirovannaya i utochnyonnaya kitayskaya traditsiya [Chinese Acupuncture. Classified and Refined Chinese Tradition]. Moscow, Profit Stajl. 536 p.

- Naghizadeh A., Hamzeheian D., Akbari S., Rezaeizadeh H., Alizadeh Vaghasloo M., Mirzaie M., Karimi M., Jafari M., 2019. Revisiting Temperaments with a Fine-Tuned Categorization Using Iranian Traditional Medicine General Ontology. Preprints. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201911.0024.v1

- Nichols R., 2021. Understanding East Asian Holistic Cognitive Style and Its Cultural Evolution: A Multi-Disciplinary Case Study of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, vol. 5, pp. 17-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41809-021-00075-8

- Ovechkin A.M., 1991. Osnovy chzchen-tsziu terapii [Basics of Zhen-ju Therapy]. Moscow, Golos Publ. 417 p.

- Peterson R.J., 2021. We Need to Address Ableism in Science. Mol Biol Cell, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 507-510. DOI:10.1091/mbc.E20-09-0616

- Popovkina G.S., 2022. Traditsionnaya kitayskaia meditsina v kontekste pandemii Covid-19 v russkoiazychnykh SMI i nauchnykh publikatsiyakh [Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Russian-Language Media and Scientific Publications]. Oriental Institute Journal, no. 4, pp. 76-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24866/2542-1611/2022-4/76-86

- Pushkarskaya N.V., 2021. Pyat stikhii v sovremennoi kulture Kitaya [Five Phases in the Modern Chinese Culture]. Filosofiya i kultura = Philosophy and Culture, no. 1, pp. 10-29.

- Shang B., Zhang H., Lu Y., Zhou X., Wang Y., Ma M., Ma K., 2020. Insights from the Perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine to Elucidate Association of Lily Disease and Yin Deficiency and Internal Heat of Depression. Evidence-Based Complementary Alternative Medicine, art. 8899079. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8899079

- Slingerland E., 2013. Body and Mind in Early China: An Integrated Humanities–Science Approach. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 81, no. 1, March 2013, pp. 6-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfs094

- Soltész F., Szűcs D., 2014. Neural Adaptation to Non-Symbolic Number and Visual Shape: An Electrophysiological Study. Biological Psychology, vol. 103, pp. 203-211. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.09.006

- Solodun V.I., 2024. Lozhnaya meditsina v pechatnykh izdaniakh na primere gazety “Pro zdorovye” [False Medicine in Print Media on the Example of the Newspaper “About Health”]. Molodoy uchenyy, no. 3 (502), pp. 528-533.

- Spirin V.S., 2006. Postroenie drevnekitaiskikh tekstov [Construction of Ancient Chinese Texts]. Saint Petersburg, St. Petersburg Oriental Studies. 276 p.

- Sun Q., 2020. O narodnom obychae v kitayskoy natsii [On Chinese Folk Customs]. Kultura i tsivilizatsiya [Culture and Сivilization], vol. 10, iss. 3А, pp. 92-97. DOI: 10.34670/AR.2020.49.43.011

- Tychinskikh Z.A., Zinnatullina G.I., 2022. Elementy shamanizma v narodnoy meditsine sibirsikh tatar [Elements of Shamanism in the Folk Medicine of the Siberian Tatars]. Genesis: istoricheskie issledovania, no. 12, pp. 51-61. DOI: 10.25136/2409-868X.2022.12.39304

- Wang H., 2019. Filosofia daosizma i kitaiskaya traditsionnaya medicina [Philosophy of Taoism and Chinese Traditional Medicine]. Bulletin of the Kalmyk State University, no. 1 (41), pp. 126-132.

- Wang H., Kuzmenko G.N., 2023. Problema nauchnogo statusa tratsionnoy kitayskoy meditsyny v Kitae [Problem of the Scientific Status of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China]. MSU Journal of Philosophical Sciences, no. 1 (45), pp. 68-78. DOI: 10.25688/2078-9238.2023.45.1.5

- Wong B.W.L., Huo Sh., Maurer U., 2024. Adaptation Patterns and Their Associations with Mismatch Negativity (MMN): A EEG Study with Controlled Expectations. Advance. March 19, 2. DOI: 10.22541/au.168323405.54729335/v2

- Wu P., 2018. Semantika tsvetooboznacheiya ZHELTY v kitayskoy i russkoy linngvokulturakh [Semantics of YELLOW Color Terms in Chinese and Russian Linguocultures]. RUDN Journal of Language Studies, Semiotics and Semantics, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 729-746. DOI: 10.22363/2313-2299-2018-9-3-729-746

- Zinken J., Hellsten I., Nerlich B., 2008. Discourse Metaphors. Body, Language and Mind. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 243-256.

- Yuan Liying, Huang Yaxin, 2023. Sopostavlenie russkikh i kitaiskikh evfemizmov, opredelyayuschikh fiziologicheskie osobennosti cheloveka [Comparison of Russian and Chinese Euphemisms Defining the Physiological Characteristics of a Person]. Sovremennoye pedagogicheskoye obrazovanie [Modern Pedagogical Education], no. 9, pp. 336-340.

- Qin J.Z., Chen B.T., 2004. Digital Model of the Theory of Yin and Yang in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Academic Journal of the First Medical College of PLA, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 933-934. (In Chinese).