Mongol warriors of the Jochi ulus at the Karasuyr cemetery, Ulytau, Central Kazakhstan

Автор: Usmanova E.R., Dremov I.I., Panyushkina I.P., Kolbina A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145357

IDR: 145145357 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.106-113

Текст обзорной статьи Mongol warriors of the Jochi ulus at the Karasuyr cemetery, Ulytau, Central Kazakhstan

In the middle of 13th and 14th centuries, the Jochi and Jochi Ulus clans controlled the territory of Desht-i-Kypchak that stretched from the Emba River in the west to the Irtysh River in the east, and from Southern Siberia in the north to the lower reaches of Syr-Darya River in the south. Little is known about the socio-political life of smaller clans because they had not been conducting active foreign policy under the sovereignty of Jochi Ulus. Yet, never-ending internal fights over the power and resources between various small clans and tribes were common and created local military conflicts. The Orda Khan, as his father the Jochi Khan, held the field headquarters at the Desht-i-Kypchak and somewhere on the Irtysh River. The territory of Saryarka, Ulytau (southwestern part of Kazakh Uplands) belonged to the Orduicids, who were fully independent from their Great Steppe vassals and

The historical landscape of Ulytau (southwestern part of the Kazakh Uplands) includes medieval settlements, fortresses, and other defensive structures, which indicates some urban development and defense planning in the region during the Golden Horde. Some researchers even place the capital (stavka) of Jochi Khan in the area of Ulytau (Smailov, 2015: 28). Islamic funerary tradition represented by mausoleums and necropolises is commonly seen on the landscape. However, early pre-Islamic burials have been recently documented in the eastern part of Jochi Ulus and poorly investigated by archaeologists. There are only few excavated burials from the Golden Horde times in Central Kazakhstan (e.g. burials on the floodplains of Nura, Ashishu, and Ishim Rivers valley), which are associated with the syncretic funeral rite resulted from a mix of the Turkic and Mongolian traditions (Margulan, 1959; Varfolomeev, Kukushkin, Dmitriev, 2017; Akishev, Khasenova, Motov, 2008).

Historical sources suggest that many representatives of various Jochi clans had continuously fought among themselves, challenging the power of the Genghis Khan successors (sons and grandsons). The relatively small scale of these military conflicts resulted in small size of burial sites, which makes difficult to recognize and investigate the burials on the landscape. This paper presents the results of archaeological excavation of the Golden Horde burial site from a military conflict zone at the Ulytau. The burial site had been accidentally discovered during reconnaissance fieldwork on localization of battles between the Kazakhs and the Jungars through the first half of the 18th century (Erofeeva, Aubekerov, 2010). The goals of this study are to establish calendar dates for the burials and to determine social, religious, and cultural standings of buried Mongols at the Ulytau, the eastern province of Jochi Ulus.

Description of archaeological and anthropological materials

The Karasuyr cemetery is located in the Sarysu River basin, which is between the Bulanta and Kalmakkyrgan Rivers in Ulytausky District, Karaganda Region,

0 50 cm

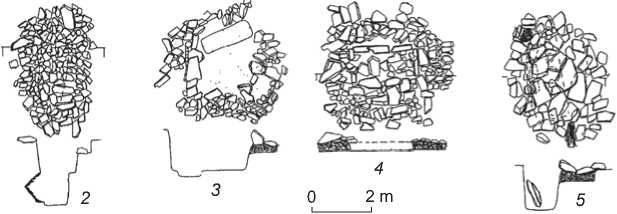

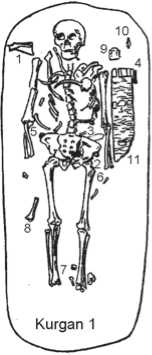

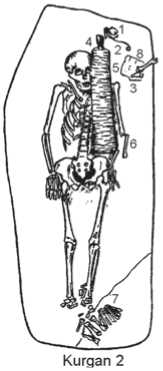

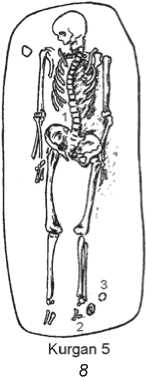

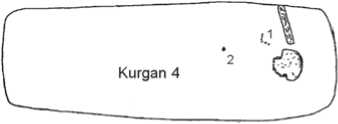

Fig. 1. Stone constructions above graves ( 1–5 ) and burial plans ( 6–10 ) of excavations at the Karasuyr cemetery.

Kurgan 1: 1 – ram shoulder blade, 2–4 – iron objects; 5 – fire steel with flint plate; 6 – iron plate; 7 – astragal with notches; 8 – ram leg bone; 9 – iron plates of laminar armor; 10 – unidentified iron plates; 11 – birch-bark quiver. Kurgan 2: 1 – details of bell; 2 – iron hook; 3 – leg bone of sheep; 4 – iron and bone arrowheads; 5 – birch-bark quiver; 6 – spatula-shaped bone liner for longbow; 7 –sheep bones (ribs, shin, scapula); 8 – flint plate. Kurgan 3: 1 – iron knife; 2 – sheep bones; 3 – bone liner; 4 – iron arrowheads; 5 – bronze rivets; 6 – birchbark quiver; 7 – ram bone. Kurgan 4: 1 – glass beads, 2 – bone buckle. Kurgan 5: 1 – iron piercing needle; 2 – iron fire steel; 3 – iron ring.

Republic of Kazakhstan. About twenty burial structures were documented in the vicinity of Karasuyr Hill (47°20′28.8′′ N, 66°24′32.3′′ E), five of which were excavated by E.R. Usmanova in 2011 (Usmanova, Dremov, Panyushkina, 2015). Four structures are built in ravines on the southern slope of this hill. Randomly stacked boulders form the grave stones measured 4–5 m across and up to 0.5 – 0.7 m in height (Fig. 1, 1–3 , 5 ), which we designate as kurgans. Two kurgans (1 and 5) had obelisks made from local black quartzite (Fig. 2, 2 , 10 ). Kurgan 5 also had an anthropomorphic stele from gray shale (Fig. 2, 11 ). The last excavated kurgan 4 was on the top of the hill and had a round shape arranged by small stones in several layers with no mortar. The shallow grave of this kurgan (0.5 m deep) was outlined with flat stones along the sides (Fig. 1, 4 , 9 ). Each kurgan holds one buried human body placed in a rectangular pit measuring 1 × 2 m in size and 1.2–1.4 m in depth. All buried individuals were stretched out on their backs, hands along their bodies, and heads turned to the north (kurgan 1, 2, 5; Fig. 1, 6–8 ), or the northeast (kurgan 3; Fig. 1, 10 ), or the east (kurgan 4; Fig. 1, 9 ). The skull front is found facing upward (kurgan 1, 2), or to the right, the southeast (kurgan 5), or half-turn to the left, the south (kurgan 3).

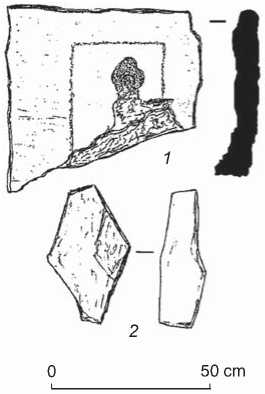

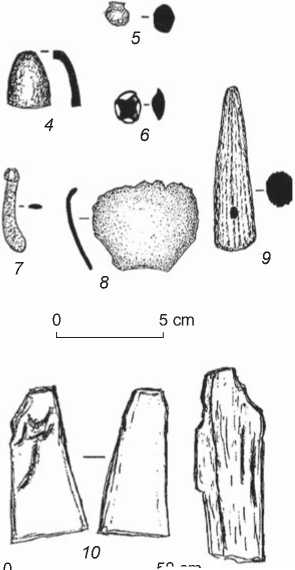

Burial assemblage. The burial assemblage includes three fire steels with flints (kurgan 1–3; Fig. 3, 6, 12, 13), two iron single-edged knives, five iron arrowheads (Fig. 3, 14–18), three bone arrowheads (Fig. 3, 9, 10), iron plates from laminar armor (two sets of several plates) (Fig. 3, 5, 11), three birch-bark quivers (two of them decorated with geometric-ornamented bone plates) (Fig. 3, 1–4), two spatula-like bone liners for a longbow (Fig. 3, 8), an iron belt buckle (Fig. 3, 7), and a quiver hook. Preservation of iron objects is poor. A sheep shoulder blade with sharp cut edge and a sheep astragal with three incisions were found in kurgan 1. Kurgans 1–3 had many small cattle bones (legs, ribs, vertebrae) in the pits.

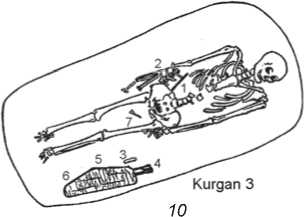

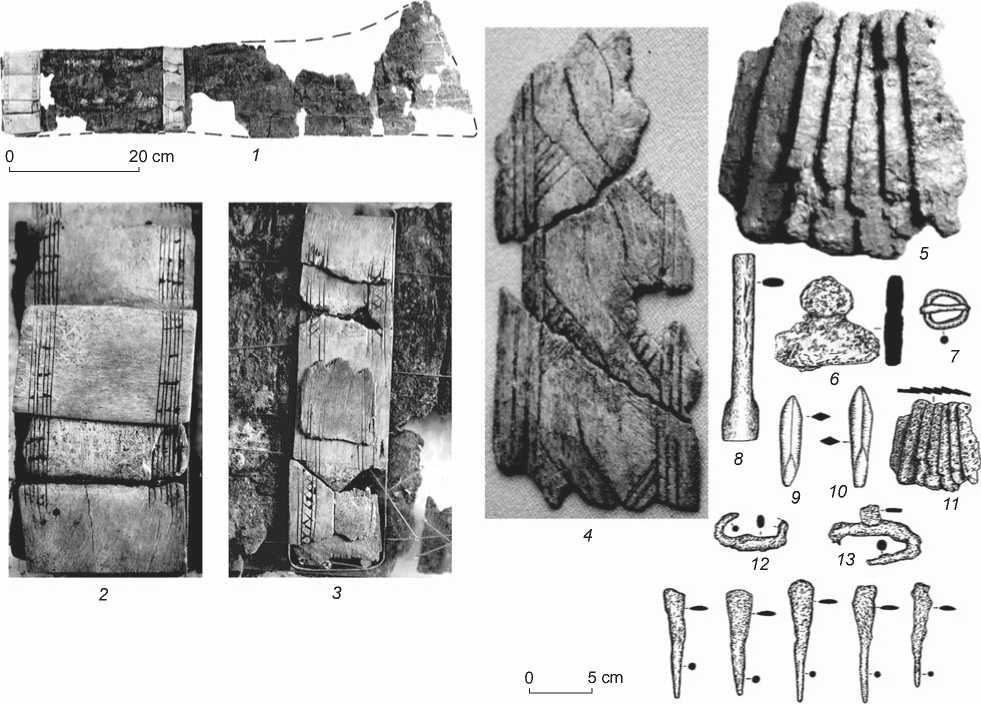

Kurgan 2 comprised two unusual artifacts related to the funeral rite: a bell and an iron hook placed near the skull. The bell was shaped as a cone folded from an iron plate about 2 cm in length and 1.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 2, 4 ). The bell interior included an iron crescentshaped tongue up to 3 cm long (Fig. 2, 7 ), and two iron rivets (Fig. 2, 5 , 6 ). The bell included a bronze thin halfway-bent plate about 4 cm in size, with holes stamped along the lower edges (Fig. 2, 8 ). It is possible that the plate functioned as a case for the bell. Below the bell was an open-end horn up to 5 cm long and 1.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 2, 9 ), and poorly preserved fragments of an iron hook about 10 cm long.

The bronze plate of the bell was covered with a fragment of a two-layer lampas-type fabric. The pattern

Fig. 2. Buddhist ritual objects.

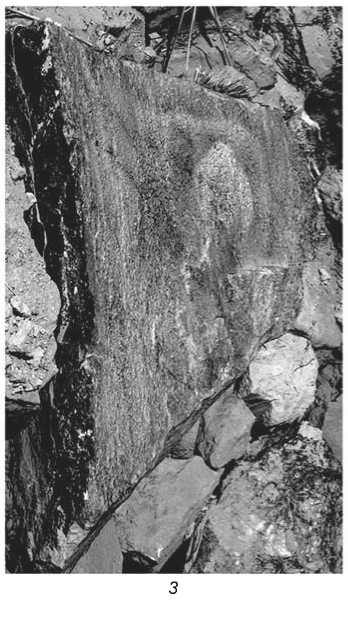

1, 3 – stone slab with carved Buddhist image—Burkhan; 2, 10 – obelisks; 4–9 – details of bell; 11 – stele. 1–3 – kurgan 1; 4–9 – kurgan 2; 10, 11 – kurgan 5.

50 cm

-1 11

14 15 16 17 18

Fig. 3 . Funeral objects of Mongolian warriors.

1–3 – fragments of quivers with decorative bone plates; 4 – bone liner for quiver; 5 , 11 – iron plates from laminar armor; 6 , 12 , 13 – fire steels; 7 – iron buckle; 8 – spatula-shaped bone liner for longbow; 9 , 10 – bone arrowheads; 14–18 – iron arrowheads.

1–3 , 5–7 , 11 – kurgan 1; 4 , 16 , 18 – kurgan 3; 8–10 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 – kurgan 2; 13 – kurgan 5.

of fabric held golden threads. The weaving technic with the use of golden threads suggests the fabric could be produced in Iran or China that traded such textiles between the 13th and 14th centuries (Orfinskaya, Usmanova, 2015). Probably, the bell was placed inside a bronze-platted case covered with lampas textile and locked with two rivet clasps (like a clutch).

The next intriguing find was a horizontally lying stone slab with an image of Burkhan (Fig. 2, 1, 3), placed at the western side of kurgan 1 grave stone. The trapezoidal-shaped slab is made of gray-greenish quartzite measuring 60 cm in the width and 55–36 cm in the height. The surface of the slab is flat but not polished and shows natural roughness. Clear image of a human head* with long ears and halo over the head could be seen following the chipped edges and irregularities of the surface. Natural irregularities of the stone surface make the torso below the head. The halo and headdress show preserved traces of stone carving: abrasion leveling and dotted striking*. The sculpted slab shows a good craftsmanship through using natural texture of stone and applying simple carving techniques while creating the artistic image of a person.

Another stone with the evidence of sculpting was lining the south side of the kurgan 5 grave stones. It was a flat grey-colored slab of slate (0.85 m long and 0.34 m wide) that originally could have been standing vertically. The slab also has a clearly marked image of anthropomorphic form (Fig. 2, 11 ).

Anthropological description of buried individuals. Radiometric dating of a rib bone from kurgan 1 was performed at the NSF AMS Facilities of University of Arizona. Radiocarbon age of the specimen (AA103462) is 707 ± 44 BP. The calibrated age of this date calculated

*Description was made from photograph by A.N. Daumann of Institute of Archaeology of RAS, Moscow.

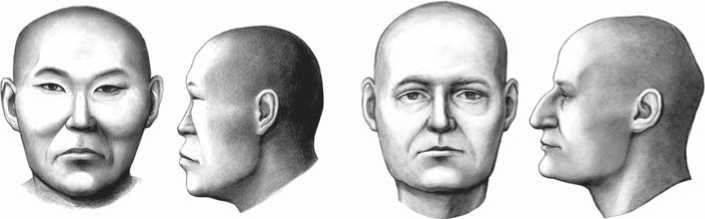

Fig. 4. Facial reconstruction made by E.A. Alekseeva (Institute of Northern Development of SB RAS). 1 – kurgan 1; 2 – kurgan 5.

with the Calib 7.1 program using the IntCal-13 calibration curve ranges between 1260 and 1300 CE (1 σ) or 1220 and 1320 CE (2 σ). The radiocarbon date places the studied funeral assemblage between the end of 13th and the beginning of 14th centuries. The calibrated interval of burial construction corresponds well with the archaeological age of the weapons and military ammunition. The found arrowheads, laminar armor, and bone liner for long-bow are directly associated with the Golden Horde chronology (Hudiakov, 2009).

The craniological analysis suggests that the skeleton of kurgan 2 belongs to a 25 – 30 year old male, whereas skeletons of kurgans 1, 3, and 5 are 40 – 55 year old males. The men buried in kurgans 1–3 belong to Mongoloid lineage from Central Asia, which today is represented by Mongols, Kalmyks, and Buryats (Fig. 4, 1 ). Surprisingly, the skeleton buried in kurgan 5 is a Caucasian male (Fig. 4, 2 ). This burial did not include any arms or military ammunition, but other funeral objects like fire steel and flint are present. The north-fixed orientation of skeleton places this individual into a contemporaneous context along with the rest buried males.

The skeletons of three individuals show age-related sprains on the vertebrae, and phalanges of the fingers and heel bones. The individuals from kurgans 1 and 5 carry degenerative-dystrophic changes in the spine. The kurgan 1 skeleton bears deforming arthritis in the second and third cervical vertebrae. This pathology limits the turning amplitude of head and neck. The 10th thoracic vertebra has a large abnormal tissue growth (osteophyte). Despite relatively young age, the skeleton of kurgan 2 has evidence of growth pathology in the lumbar region related to spinal stenosis. This pathology is associated with early childhood physical stress and heavy horseback riding.

The race of individual buried in kurgan 4 is not identified due to poor preservation of skull. This burial has an oriental “Turkic” orientation and differs from other kurgans with the north-fixed orientation. The kurgan assemblage includes 12 opaque glass beads and a bone clasp placed below the skull. The bead making technique suggests its origin in the Middle East or Near East*. The beads could be a part of female headdress or neck decoration.

Chronological and cultural affiliation of Karasuyr cemetery

The funeral rite of medieval Mongols comprises two main elements: a north or northeast alignment of the skeleton, and occurrence of sheep bones next to the head of buried individual. Sheep bones from legs and vertebrae are most commonly found in the graves. This tradition dominates the funeral rite of Mongols from the 11th century. Consequently, the Mongol tribes introduced this funeral rite to the entire territory of Desht-i-Kypchak during the Golden Horde (13th – 14th centuries) (Kostyukov, 2010: 53).

The funeral rite of the Karasuyr cemetery includes sacrificial offering of sheep. In kurgan 2, a sheep tibia from a rear leg was dug-in vertically, and other bones of the sheep (sternum, scapula, and fore shank) were placed next to the skeleton feet. In kurgan 3, ram bones from the fore shank were present, three of which were found on the top of the left arm radius. There were bones of four sheep slaughtered at the age of 13 – 36 months**. Most of the bones came from the left side of the sheep’s body, which may have a ritual significance. Usually, the meat was consumed during the wake, and clean bones were buried (kurgan 1 and 3). In some cases, we find traces of rodent teeth marks on the sheep bones, which suggests placement of meat cuts (kurgan 2).

The described funeral rite of studied kurgans associates the Karasuyr cemetery with Mongol burial tradition. In the studied region, the Mongol burial rite of the 13th– 14th centuries includes the north-fixed position of skeleton with occasional deviation to the east, and placement of sheep bones (leg) inside the graves (Akishev, Khasenova, Motov, 2008: 62).

Religious and social affiliation of buried individuals

The Tibetan tradition of Buddhism spread into the Mongol Empire by the middle of the 13th century under the leadership of Kunga Gyeltsen (1182 – 1251), the leader of Sakya school of Buddhism. Kunga Gyeltsen was a tutor of Godan, son of Ögadei Khan—the third son of Genghis Khan, and later Kublai Khan (1215 – 1294), who were the most renowned propagators of Tibetan Buddhism among the Mongolian aristocracy. Tibetans were semi-nomadic people practicing Buddhism adopted to their nomadic way of living. At the ordinary level, Tibetan Buddhism has many similarities with Mongolian shamanism. This similarity of beliefs has prompted the quick spread of Tibetan Buddhism into the Mongolian steppe (e.g. Obychai…, s.a.). Tibetan Buddhism is less restrictive in the funeral rite than other religions. The high diversity of burial rituals practiced by priests depended on date of birth and social status of deceased, season, etc. Yet, Buddhist ritual objects placed inside a grave are most important to the funeral rite. The funeral rite of Lamaism embraces both ancient pagan practices and Buddhist custom (Gerasimova, 1992: 151). This approach consists of a wide variety of choices for the placement of burials (top of mountain, mountain slope, river banks, water, on trees, etc.) and burial type (e.g. inhumation, cremation, or mummification) (Nefedyev, 1834: 201 – 202; Tucci, 2005: 308).

All studied kurgans at the Karasuyr cemetery (except kurgan 4, which is most likely a later Turkic burial) are located on the southern slope of the hill. This kurgan arrangement corresponds well to both the Buddhist and Mongol traditions. The common belief of Buddhists in the Mountain of Kailash refers to a sacred role of the south placement. For this very reason, gates of Buddhist temples are built at the south (Sodnompilova, 2005: 239 – 240). The burial rite of the studied kurgan belongs to the Lamaism funeral tradition of inhumation. The well-preserved organic material of armory but the lack of other organic traces associated with cloth suggests that the dead people were buried naked. The position of skeletons indicates no bindings or wrappings used in the burial, which is common in Islamic tradition. There were no special manipulations observed on the skeletons, with one exception. In kurgan 2, the buried male had the fingers of the right hand bent inward, and the heels turned upward.

The burial artifacts also include other religious objects associated with Tibetan Buddhism such as tombstone with an image of Buddhist Burkhan (kurgan 1), set of bells and an iron hook (kurgan 2). The bells are found in shamanic and folk Buddhist rituals in the Altai and Tibet regions. In Lamaism, the bell is usually accompanied by a vajra. It is possible that the metal hook represents a vajra*.

Kurgan 1 had objects of Mongol shamanistic practice, i.e., astragal with three incisions and ram scapula with a cut-off side. Both Mongolian and Turkic shamans used these objects in the past. Yet, Mongolians, Khazaro-Mongols, and Kalmyks used them in fortune-telling rituals (Dalna Merga) through modern times (Mohammadi, 2016). G. Tucci describes the long-time lasting tradition of fortune telling using sheep bones in the Lamaism (2005: 255).

Overall, the burial composition and assemblage of the studied kurgans are homogeneous, although specific features of kurgan 1 and 5 suggest some social dynamics of the buried group. The three burials of the mongoloid males (kurgan 1, 2 and 3) had weaponry fragments of bows, arrows, and quiver placed on the left side of skeleton, which indicate the military status of the buried. The variety of funeral artifacts suggests that the warrior from kurgan 1 had the highest rank in the group. The weaponry assemblage of this kurgan was most prominent; moreover, the burial included the sheep bones used for funeral offerings and fortune telling, and the Buddhist-image carved tombstone. The burial had an unusually rich quiver with well-defined trapezoidal shape made of two-layer folded birch-bark. The upper part of the quiver was decorated with bone plates and engravings of 4–5 horizontal lines pained black (Fig. 3, 1–3 ). The kurgan also had the largest seven-plate fragment of laminar armor (Fig. 3, 5 , 11 ). The kurgan 1 funeral assemblage is linked to Buddhist, shamanic and military attributes, and indicates the social status of the buried warrior. Most likely, this was a shaman warrior practicing Tibetan Buddhism and the military group leader.

In opposite, the Caucasian male from kurgan 5 (Fig. 4, 1 ) had no weaponry and very small number of funeral objects that place him to a subordinate position in the military group and low social status. According to the social classification of Mongol society developed by B.Y. Vladimirtsov, the Caucasian male may belong to the third social class that comprises slaves or servants with no personal property, and who often being war prisoners or individuals of other ethnic groups (not Mongols) (2002: 414). With time they could move up in the social strata and become commoners.

Being a Mongolian warrior is associated with a horseback-mounted archery. The typical armory of Mongolian combat solders includes bows, arrows, quiver, lasso, knife, and saber (Gorelik, 2002). Traditionally, the primary structure of the Mongolian army was organized with a 10-people unit called desyatka, led by foremen, usually from not prominent families or immigrants, who did not belong to the elite of the Mongol aristocracy. The military burials of the Karasuyr cemetery probably belong to killed members of a desyatka, about which Vladimirtsov wrote: “Simple soldiers were at the first place… By origin, they belonged to families of various Mongolian clans that were below the steppe aristocracy. These were unaganbogol’am—families who followed the Genghis Khan and jointed the Mongol troops voluntarily. Unaganbogol’am natives commonly served as the foremen and, in some cases, as the centurions” (2002: 414).

Conclusions

The burial rite of the Karasuyr cemetery includes the following attributes of Mongolian funeral tradition and Tibetan Buddhism:

-

- Grave setting in a ravine or a gorge on the southern slope of a mountain;

-

- Construction of oval stone mound with vertically installed stone obelisk;

-

- North or northeast orientation of skeletons;

-

- Placement of vertically entrenched bone of a ram’s leg.

The funeral assemblage of three excavated graves represents a burial complex combining Buddhist attributes, military arms, and sacrificial offerings. The burial complex is clearly associated with the Mongol nomadic tradition and more remarkably with the religious syncretism of Lamaism, which blends the basic postulates of Tibetan Buddhism and shamanistic beliefs.

Burials from the Karasuyr site belong to the period of Mongol history when Mongol nomads freely practiced shamanism and Buddhism, and had not been resisting the conversion into Islam. While it is impossible to name the event that resulted in the death of these warriors buried at the Karasuyr, we hypothesize that their death resulted from a combat conflict in the eastern province of Jochi Ulus (also called the Golden Horde). The burials were constructed simultaneously. Lack of arms, the small number of funeral objects, and a fragment of iron chain found in the grave of Caucasian male (kurgan 5) indicate a subordinate position of this individual in the military group. The occurrence of the Caucasian in the Mongol military group is not an extraordinary phenomenon. Many written documents of merchants and explorers traveling at that time across the Golden Horde territory describe meeting people of various ethnic backgrounds including Europeans.

Thus, the presented synthesis of absolute dating, craniological analysis, funerary rite, arms, and cultural artifacts classify the studied burial site at the Karasuyr as a combat cemetery of Jochi Ulus warriors during the early phase of Buddhism movement among the Mongolian tribes.

Acknowledgements

Field archaeology was performed in 2011 under the project “Archaeological Research of Sites in the Boulanty-Beleutty Interfluve” (directed by I.V. Erofeeva) under the research program of Kazakh Scientific Research Institute on Problems of the Cultural Heritage of Nomads. Analytic processing was performed under the project “Study and Documentation of Cultural Landscapes of Central Kazakhstan with the Use of Modern Techniques and Interdisciplinary Approaches” funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP05132595).

We are grateful to B.S. Kozhekhmetov, Director of Ulytau State National Nature Park, V.M. Zaitsev (AOZT Aray , Lisakovsk) for support of this research; to A.S. Suslov, Y.E. Parshin, S.L. Ladynsky, S.V. Kolesnikov, S.K. Tazhibaev, L.D. Kogay, V.V. Kryukov, and A.Z. Baydildinov for the field assistance; and to Scientific Restoration Lab “ Ostrov Krym” (Almaty) for help with the artifact conservation.