“Mountains” on the draft of the land of fort Narym by S.U. Remezov

Автор: Barsukov E.V., Chernaya M.P.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article describes an unusual source—the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” from the “Sketchbook of Siberia” by Semen Remezov. This is a spatial-graphic model, rendering late 17th-century realities in a conventional schematic manner. It covers the Narymsky and Ketsky uyezds (currently, northern Tomsk Region, known as Narym Territory). The encoded information relates to the history, geography, ethnography, settlement, and infrastructure at this territory in the late 17th century. One of the features represents elevations. We discuss its accuracy and relevance to the history and culture of the Narym Territory, and outline the ways of solving related problems. To render elevations, the cartographer used two types of conventional signs: those actually representing mountains and ranges, and thick lines. We conclude that “mountains” on the draft refer to real geographic features of the Narym Territory, described by 17th–19th century travelers and scholars and by the local oral tradition, and supported by modern geographical records. S.U. Remezov represented elevated areas with reference to their practical meaning for Russian reclamation.

Draft of the land of fort narym, s.u. remezov, mountains, 17th–19th centuries, historical and geographical context, methods of analyzing spatial symbols

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146877

IDR: 145146877 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.2.120-128

Текст научной статьи “Mountains” on the draft of the land of fort Narym by S.U. Remezov

The process of development of Siberia is reflected in various cartographic materials. These included geographical drafts attached to descriptions of new lands ( rospisi ), which already in the 17th century became common reporting documents compiled at the request of the government, making it possible for the central and local administration to direct, monitor, control, and regulate the processes of settlement and development of the vast Siberian lands.

The history of study of the S.U. Remezov’s heritage begins with publication of the Sketchbook of Siberia in the late 19th century, which made this unique document accessible to many scholars. Over the following almost 150 years of analyzing rich information provided in atlases, a wide range of scholarly literature has emerged (Andreev, 1940; Goldenberg, 1990; Umansky, 1996; Matveev, 2009; Tikhonov, 2013; and others). Specialists in various disciplines have discussed Remezov’s maps in terms of various scientific scopes and specific objectives. Although we are unable to give a detailed historiographic review, we should acknowledge the undoubtably valuable contribution of our predecessors to revealing the information capacity of these maps.

Remezov’s atlases contain a great array of primary evidence collected and compiled in the field. This is all the more important because a large amount of original evidence has perished under various circumstances, while information selected and systematized on the basis of it has survived only in Remezov’s “sketchbooks”. Like any cartographic document, Remezov’s drafts represent a spatial-graphic model, reproducing reality in a conventional schematic form. The process of mapping involved an inevitable generalization of the displayed realities, which also implied mandatory selection of the most substantial and meaningful features. The mapmaker selected the objects from the natural and historical landscape, as well as the means of rendering them on the draft (Chernaya, 2002: 10– 13). When creating his maps, Remezov was not only focused on accurately depicting the area’s features, but also prioritized selecting elements that would be useful for land development. As a serviceman and the son of a boyar, he carried out his work “by the decree of the Great Sovereign”; hence, he viewed the hierarchical importance of the parts of the map through a practical lens, giving primary importance to the reliability and usefulness of the objects depicted.

Indeed, one should take a critical and differentiated approach to assessing how adequately the objects were represented on Remezov’s drafts. This study intends to analyze one of the elements called “mountain(s)”, and to establish geographical and historical facts hidden behind it. This will be done by using the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” from the “Sketchbook of Siberia” (Chertyozhnaya kniga…, 1882: Fol. 10). This article initiates a series of publications presenting a detailed historical, geographical, and archaeological analysis of this unique source.

A.V. Kontev noted that the name “mountain” was absent from Russian maps until the late 17th century, and appeared only on the drafts by Remezov (2022: 163). Kontev also cited the opinion of C. Kudachinova that mountains in Russian sketch maps were “either reduced… to short thick bands, which almost did not differ from water flows, or were ignored for the sake of ample depiction of rivers… There was no obvious need to depict them. They played an insignificant role, if any, in the Russian world… Unlike rivers, natural elevations were too extravagant and had no special value that would make them worthy of being represented” (Ibid.: 163–164).

Elevations on the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym”

We should analyze the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” (hereafter, the “Draft”), where the objects

“mountain(s)” were marked, and try to discover why Remezov considered them “worthy to be represented”. At the time of its creation, the “Draft” covered the Narymsky and Ketsky uyezds, populated mainly by the Selkups, as well as the southern part of the Surgutsky Uyezd, which included the Vasyugan and Tym River basins, where the population was apparently a mix of the Selkups and Khanty. On modern maps, the territory represented on the “Draft” is located in the northern part of the Tomsk Region, almost completely occupying its four largest districts. Despite several administrative transformations, this territory is known as the “Narym land”.

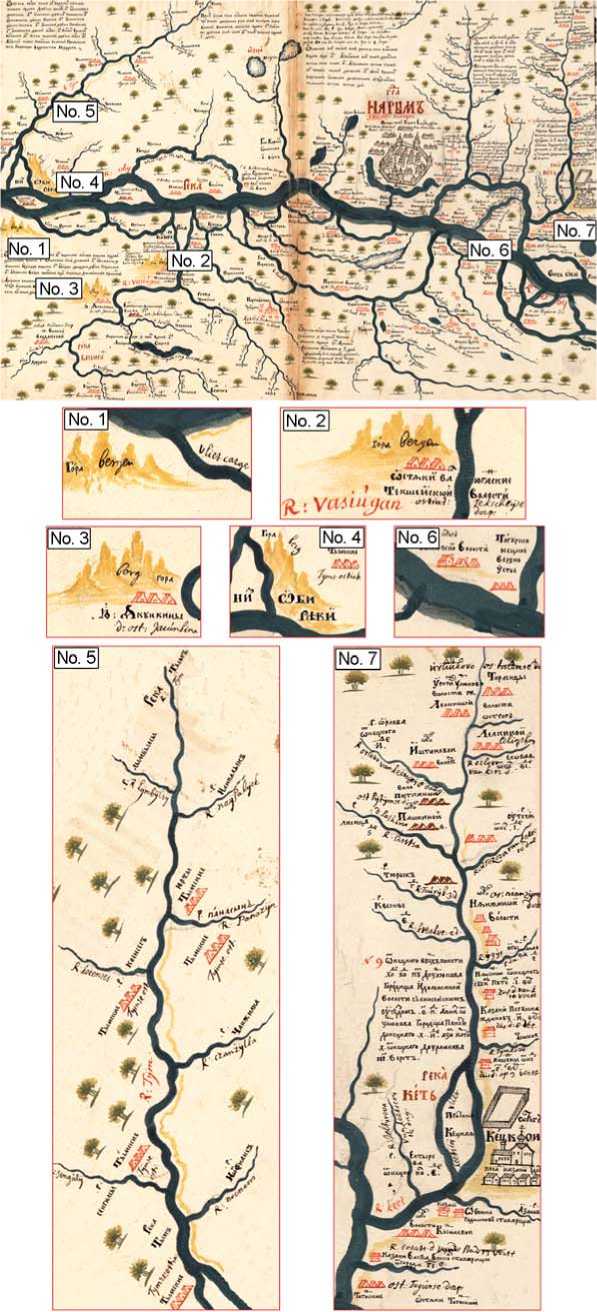

High swampiness, which implies low-lying landscape, is the hallmark of the region. Although information about the features of the terrain, even in the late 19th century, was relatively modest, the conclusions in a few summarizing works were unambiguous: “There are no mountains in the entire space of the Narym land” (Kostrov, 1872: 1); “Narym means swamp, a swampy country, which quite correctly describes this area, not at all rich in elevations” (Plotnikov, 1901: 1, 3). In the context of these conclusions, the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” is of undoubted interest, since even a cursory acquaintance with the “Draft” gives a different idea of the natural and geographical situation in the region. The conventional signs used by Remezov include those that are unambiguously interpreted as positive topographic forms, such as various elevations of several types (see Figure ). Taking into account the prevailing notions about the Narym region, this particular detail seems contradictory. Additionally, the “Draft of the Town of Tomsk” (which encompasses the northern foothills of the Kuznetsk Alatau and is adjacent to Narym) does not feature any such markings (Chertyozhnaya kniga…, 1882: Fol. 11).

It is possible that a clear lack of information on the geography of remote parts of Siberia, one of which was the Narym land, in the 17th century, was the reason behind inaccuracies and errors, including those in rendering the terrain. A good illustration is the “Plan of the Town of Narym” published by N. Witsen, where a mountain range with “peaks into the sky”—nonsense for the marshy Narym region—is located behind the residential area (Okladnaya kniga…, 2015: 186–187).

As a working hypothesis, we suggest that Remezov used conventional signs for positive topographic forms not formally, but with objective reasons associated with the subsistence system of local inhabitants, information about which was available to cartographers of the 17th century. Let us analyze the hypothesis in the context of modern geographical knowledge and information from written sources, for establishing the importance of these elements of terrain for the life of the local population.

Positive topographic forms on the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” by S.U. Remezov (Chertyozhnaya kniga…, 1882: 10).

Remezov used two types of conventional sign for designating positive topographic forms, which differed greatly in the manner of execution, but were painted yellow-brown of varying intensity. The first type is undoubtedly associated with the depiction of a mountain range, or an individual mountain. The visual identity of their execution on the “Draft” makes it possible to combine these signs into a single group. In addition, such images were supplemented with a clarifying inscription in Russian and Dutch. Two variants have been identified: in the first case, the indicator “mountain” was supplemented by the Dutch “berg”, while in the second case, the same Russian term was given with the stress on the first syllable ( góra ) and was accompanied by the Dutch word “bergen”, which indicates the plural.

The second type of conventional sign is a thick line, painted yellow-brown in the same way as “mountains”. This designation was usually confined to the valleys of large rivers; the line runs parallel to the channel, often repeating its bends. If the symbol crosses any river or its tributary, the line is interrupted and continues on the other bank.

The first travelers and scholars who were familiar with the region first-hand agreed that all natural elevations there were associated with river channels. The local population called them uvaly (‘slightly sloping extended hills’) and riverbank cliffs (Kostrov, 1872: 1). On the “Draft”, symbols of elevations are also associated with main watercourses, which clearly demonstrates their specific localization linked only to four rivers—the Ob, Tym, Vasyugan, and Ket. This is not surprising, since even in the second half of the 19th century, distinctive “ridges and riverbank cliffs” were mentioned only with reference to the Ob, Ket, and Vasyugan rivers (Ibid.).

The northernmost elevation is located on the left bank of the Ob River, approximately opposite the delta of the Tym River (see Figure , No. 1). It is indicated by the drawing of mountains and inscription “góra–bergen” (in plural). The mountains begin at the lower mouth of the “Karge” channel, and extend parallel to the Ob channel to the border of the draft.

At this section, the Ob River valley shows pronounced asymmetry. On the left bank, floodplain terraces are rare and occupy small areas. They are concentrated mainly on the right bank, while the channel is located at the left side of the valley and approaches the watershed plateau— materik (‘continent’), exposing its geological structure in high and steep Chagin, Viskov, and Kargin yars (‘steep banks’) (Priroda…, 1968: 13–14). This “continent” and steep banks were well known to the local population and were observed by scholars and travelers who visited the Middle Ob region. One of the first persons who mentioned them was the Russian envoy to China Nikolai Spathari, who traveled along the Ob River in 1675: “…Veskov yar, with a forest on it: cedar pine, fir, spruce, meadowsweet, and many others. And at the end of that Veskov yar, there stands the yurt of the Ostyak Vesk…” (Puteshestviye…, 1882: 64). The place must have owed its name to the Ostyak Vesk. In the mid-18th century, G.F. Miller wrote in detail about steep banks in that section of the Ob River: “Beskov yar in the Ostyak language; in the Narym language, Wes-madschi, and in the Surgut language, Wes-jach-wont, an elevated steep bank on the left side of the river… which, according to the Ostyaks, should be associated with the repeatedly mentioned so-called materik . Here, however, it extends only for 4 versts along the Ob River, where it again alternates with low places… Kychagin yar, in Ostyak, Seajago-wont, on the left bank, 24 versts from the previous Beskov yar, of which it is a continuation, extends for 2 versts” (Sibir…, 1996: 200).

Viskov yar is also interesting because in July 1912, in its outcrops, paleontological excavations were carried out. The “hills of Veskov yar” were examined by the Finnish scholar K. Donner. He intended to find a mammoth skeleton, but owing to the soil’s hardness, and lack of time, he could find only several large bones, the species of which remained unclear (Donner, 2008: 44). “Veskov yar” is mentioned in the sources most often; apparently, it stood out by its physical features and impressive appearance. In addition, according to the data from the 19th century, it was used as a landmark for determining the northern border of the Narym land, which ran “4 versts from the Viskov yar locality” (Plotnikov, 1901: 1).

A section of a watershed plain in the area under discussion is separated from the Ob River valley, which constitutes the floodplain on the left bank, by a steep ledge rising 30–40 m high above the floodplain’s surface, 40– 50 m above the water line, and clearly expressed in the relief. The Ob River comes close to the plain only in a few places, forming high exposed steep banks (Priroda…, 1968: 11–12). The “continent” itself extends parallel to the Ob River for several dozens of kilometers, sometimes approaching the channel and sometimes moving away from it. In the present-day Aleksandrovsky District, this section of the watershed plain appears under the name of “Mount Poludennaya”.

As compared to the low-lying landscapes of the Narym land, the “continent” stands out for its high, steep banks that overlook the river. The local population and travelers may have even perceived them as mountains, which is evident from the place names such as “Mount Poludennaya”. The Ob part of the left-bank plain, which is intersected by several rivers and streams, is well-drained, resulting in minimal swampiness. In the Soviet period, this “progressively drained territory” was recommended for priority economic development (Ibid.: 11). Modern pipelines and the related communication corridors in the north of Tomsk Region were placed precisely on the elevated left bank. Currently, the settlements of Vertikos and Oktyabrsky are located there. In the same area, the village of Karga (Ust-Karga) is known. In the late 19th century, it was inhabited by Russian peasants, although it was situated on the lands of the indigenous population of Tym Volost (Plotnikov, 1901: 183, 245–246). The geomorphologic situation contributed to the emergence of small arable lands and vegetable gardens near the village, which was an important indicator of good prospects for the development of the Narym land (Karta naselennykh mest…, 1914).

Images of mountains identical to those described above also appear at two points on the left bank of the Vasyugan River. In the estuary section, the sign is accompanied by the inscription in plural: “góra–bergen” (see Figure , No. 2); in the middle reaches of the river, where the channel makes a huge bend, the inscription appears in singular: “gora–berg” (see Figure , No. 3). It can be logically assumed that the elevations in the Vasyugan basin indicated by Remezov were associated with the river valley, its terraces above the floodplain, and adjacent areas of the watershed. Scholars and travelers repeatedly mentioned that the Vasyugan River in its lower reaches significantly differed from the Ob River precisely by the presence of elevated banks and high yars adjacent to the riverbed (Shostakovich, 1877: 5). This was also typical of its tributaries, for example, of the Chizhapka River, about the banks of which the locals said: “The mountains are so high that the hat falls off the head when you look at the top” (Ibid.: 3).

In the 19th century, the local population called “rocks” the complexes of high promontories and outcropping yars, overlooking the Vasyugan River, which stood out against the background of the monotonous, flat Narym landscapes, and associated various legends with them. According to the surviving written evidence from the second half of the 19th century, over a dozen such “rocks” were known (Plotnikov, 1901: 194–202). Therefore, Remezov’s signs used for marking the elevations in the Vasyugan basin can be explained. However, we should keep in mind that “mountains” were indicated on specific sections of the left bank and only in two places, although, according to written information, “rocks” occurred along the entire length of the valley.

We should analyze the locations of “mountains” indicated by Remezov using modern information about the terrain and geomorphologic features of the Vasyugan River valley. A high bank can be seen on its left side, in the lower reaches, but it is no different from the opposite bank, and is even inferior to it in height. Nevertheless, the presence of the indigenous settlements in the estuary part of the Vasyugan River precisely on its left bank in the 19th century is curious. These settlements occupied the sections of high terraces facing the river, which at that time were designated by the term “pine forest bank” (Shostakovich, 1877: 5). Yurts Yugin were the first, then followed Naunak. This section is designated as a “bank with bedrock edges” on the pilot charts of the Vasyugan River. Several such areas are mentioned on the left bank in the lower reaches. As a rule, within them, settlements were located (Karta reki Vasyugan…, 1982: 98, 104). Up to the 20th century, local indigenous population preferred to settle on this segment of the left bank of the Vasyugan River, and not on the right bank. Remezov pointed to the presence of places convenient for “settlement” of peasants in one day’s journey on a boat from the mouth of the Vasyugan River (Chertyozhnaya kniga…, 1882: Fol. 10). In the swampy Narym land, such places were rather exceptional and were well-known to the indigenous population. These places, convenient for “settling”, could have been associated precisely with the “mountains” mentioned above. Thus, we believe that designation of “mountains” by Remezov in the lower reaches of the Vasyugan River could have been caused by the presence of watershed plain, which in this section approaches the river valley from the north, passing into the third terrace above the floodplain. The “pine forest bank”, in several places directly reaching the riverbed, has been used for building the settlements and utility structures of the local population for centuries.

Although the presence of “mountains” on the “Draft” in the lower reaches of the Vasyugan River finds its confirmation in the modern geographical features of that area, their designation in the middle reaches of the same river causes a number of difficulties (see Figure, No. 3). In that area, on the left bank, several high outcropping yars are identified, which are distinguished by the local population. The most interesting, and probably the most famous, is the elevation in the boundaries of the modern village of Sredny Vasyugan, which in the late 19th century was called Vasyuganskoye. The elevation is referred to as Shaitansky, Shamansky, or Shamanny promontory. Shostakovich was one of the first travelers to mention it. According to his information, Shaitansky promontory was located near the village church. A larch tree grew there, on which the locals hung “sacrifices to shaitan, so he would not cause obstacles and losses to the sacrificer; and in particular, would not go ahead of him during the hunt and chase away the animals” (Shostakovich, 1877: 14). Ten years later, N.P. Grigorovsky visited the village of Vasyuganskoye and noted the impressive size of the elevation, calling it a mountain. In fact, this is a part of a high terrace, which protruded in the form of a promontory into the channels of two watercourses—the Vasyugan River and its tributary Varingyogan River (old, Varen-Yogan). On the Vasyugan pilot chart, on this section of the bank, a part of a rock terrace is marked, and archaeologists describe this place the same way (Sredniy Vasyugan…, 2000: 8).

A legend about the origin of Shaitansky promontory was recorded from the locals in the late 19th century. Its unusual name was explained in a simple manner: “this mountain has such a name because in former times unclean spirits lived on it…”. Grigorovsky, who visited the village of Vasyuganskoye in 1883, examined the promontory and noted two sacred trees next to it. One was a fir tree, dedicated to local spirits. Many gifts for them were hung on the branches: ribbons, strings, rags (mostly red), and animal skins, as well as several arshins of chintz and other inexpensive fabric. The second tree, almost on the edge of the promontory, was a thick larch; a wooden barn (the “dwelling” of the spirit) was made near its lower branches. This place was revered not only by the indigenous people. Among the gifts, Grigorovsky saw eight arshins of chintz, which were “hung” in the autumn of 1881 by the watchman of the Vasyugan grain store, Cossack A. Sosnin, who suffered from fever all spring and summer and, on the advice of a well-known Vasyugan shaman, brought a gift to the spirits (Grigorovsky, 1884: 23). Unfortunately, already in the late 19th century, the sacred place was repeatedly robbed by visiting merchants, who knew that one could profit in such places from money and valuables left by the indigenous people in cracks and roots of a tree. Therefore, by the time Grigorovsky visited the village, the indigenous inhabitants of the Vasyugan had moved the barn with the image of the spirit to another place, which was kept secret (Ibid.).

Shaitansky promontory is known well in the archaeology of the Tomsk Region (Chindina, Yakovlev, Ozheredov, 1990: 179–181). Shostakovich—the first scholar who visited the place—discovered archaeological evidence of ancient blacksmithing: “About four versts from this place, there is another, ‘fox’ promontory, where, according to oral tradition, a forge used to be. Indeed, on an overgrown elevated sandy hill, I found waste from smithery—slag. Now, this promontory is a favorite place for pine forest birds and foxes” (1877: 14). A number of archaeological sites have been discovered there. The most famous is the lost fortified settlement of Shamansky Mys, of the Early Iron Age. A small but distinctive collection of religious bronze castings therefrom is kept in the Novosibirsk Museum of Local History.

The choice of this particular place for building a church was not accidental. First, it is situated in the middle section of the Vasyugan River, making it accessible to residents of both the upper and lower reaches. Second, this section of the riverbank held a prominent position in the middle reaches, and played a significant role in the religious practices of the local indigenous population. The construction of a church on a site that was sacred to these people was intended to maintain continuity in the religious realm, while altering the object of worship. However, this resulted in the church and the sacred site existing in parallel, as noted by the clergy. Evidently, the Narym “Draft” referred to this well-known elevation among the local population.

Remezov marked several elevations on the right bank of the Ob River. One of these was south of the mouth of the Tym (see Figure , No. 4), which flows into the Ob River in several branches. The northern (right-bank) part of the Tym delta is distinguished by extremely low elevations, which rarely exceed 50 m. The local terrain is composed of huge segments of floodplain and a heavily swampy complex of terraces above the floodplain, cut by numerous channels and residual water bodies, often swampy. There are also large and long channels in the area, including the Milya, Kievskaya, Radaika, Zharkova, Paninsky, Murasovsky Istok, etc. The watershed plain becomes visible only in the extreme northeast of the present-day Tomsk Region. Against this background, the geomorphologic situation in the area of the main mouth of the Tym River and to the south looks highly advantageous. It is no coincidence that the modern villages of Ust-Tym and Tymsk are located there. Hypsographic marks in this part exceed 60 m. Elevated, non-swampy areas suitable for development are confined to the edges of the terraces facing the streambeds. On the “Draft”, the “mountain” was indicated at the southernmost branch of the Tym River. On modern maps, it corresponds to the Langa channel, stretching from the main channel of the Tym and almost reaching the village of Tymsk. On the “Draft”, the Shedugol River (the present-day Shedelga River) is the conventional boundary of the “mountains” from the south.

In the late 19th century, the location of the village of Tymsk was described as follows: “…located on the right bank of the Ob River and the Tym channel. The place occupied by the village is where pine forest grows; it is high and consists of 34 houses” (Plotnikov, 1901: 245). K. Donner also mentioned that the village was “on the high hills”. In the 17th century, the height of the terrace in that location could have been even greater. According to information from the early 20th century, the river actively eroded the bank in this section (Donner, 2008: 20). A fragment of the terrace occupied by the village stands out against the background of low marshy spaces of the Tym delta. It was also well known to the indigenous population. There was a Selkup cemetery on the Langa channel on one of the low ridges, which in the Soviet period received the name “Myasokombinat” (Yakovlev, 1994: 36). Moreover, a section of the bank at the upper mouth of that channel was chosen for building a church and later a Russian village, many times mentioned by travelers and scholars. Already in 1740, the Tymsk cemetery with the church of the Life-Giving Trinity for the local Ostyaks was located there. Only dwellings of clergy at the church were there; there were no Russian or indigenous buildings (Sibir…, 1996: 199). These lands belonged to the indigenous people of Tym Volost. “They allotted 99 desiatinas of haying land for the clergymen from their land. Merchants, commoners, and peasants, who settled there by the permission of the indigenous people in 1820, first for fishing in the form of tenants of land, had temporary booths for living, which they later replaced by permanent dwellings and became settled residents thus forming the ‘mixed-class’ Tymsk rural society” (Plotnikov, 1901: 185).

The natural and geographical situation contributed to the development of significant areas for vegetable gardens in the village of Tymsk in the late 19th century (Karta naselennykh mest…, 1914). As compared to the opposite bank of the Ob River, which is almost 30 m higher, this area hardly looked like a mountain. Yet, Remezov did not attempt to match the elements of landscape and their height, but recorded only specific areas that for some reason were distinguished by the local population. Such was precisely the area of the bank adjacent to the southern branch of the Tym River (Langa channel), standing out against the background of the low and swampy Tym delta, which covers a segment of the right bank of the Ob River for over 100 km. Similarly to the village of Vasyuganskoye, this place was chosen for constructing a church.

On the left bank of the Tym River, Remezov marked another elevation as a yellow-brown band, stretching parallel to the channel and ending in the middle course (see Figure , No. 5). The geographical literature emphasizes that rivers on the right bank of the Ob usually have high left banks (Grigor, 1951: 158). With a similar situation on the right and left banks of the Tym River, the “continent” or watershed plateau approaches the river precisely from the south, between the former Lymbel-Karamo yurts and the mouth of the Koses River, and ends with the steep slope; in some places, there are outcrops (Barkov, 1951: 178). In the context of the problem we are discussing, we should point to two features of the Tym River valley. First, the river flows in the valley of the ancient channel, which locally has well-marked sides, with the southern one close to the channel and the northern one located several dozens of kilometers away. Second, although the hypsographic marks of the terraces at the right and left banks of the

Tym are close, modern maps and satellite images of the Tym River basin clearly show differences caused by the asymmetry of the valley. The right tributaries of the Tym are longer. For example, the length of the Sangilka River is 335 km. The left bank is not less swampy than the right bank, but the lengths of even the largest tributaries do not exceed dozens of kilometers. The watershed in the south, between the Tym and Paidugina rivers, is located on average at a distance of 12–20 km from the main channel of the Tym River, and is distinguished by significant hypsographic marks, and, most importantly, does not constitute continuous swamp. The band indicating elevation on the “Draft” ends between the mouths of the Tym tributaries Koses and Lymbelka. The watershed between the Tym and Paidugina Rivers, which has its sources in the swamps and Komarnoye lake system, ends approximately in that area. The watershed is clearly marked on the “Draft” by a straight line of conventional tree signs between the sources of the Tym tributaries and watercourses flowing from north to south. The vegetation on the right bank of the Tym River is marked differently, with trees concentrated between the Tym tributaries and not organized into any system.

The key to the “Draft” indicates the winter “sledge” route to the mouth of the Lymbelka River, where the local population hunted. It is possible that the watershed of the Tym and Paidugina Rivers was used for this purpose, in order to avoid crossing numerous valleys of the Tym tributaries. In this case, the geomorphologic features of the left bank area of the Tym, well-known to local residents, were of interest to them. These points could have been behind the designation of the elevations by Remezov precisely on the left bank. A similar conventional sign marks an elevation on the left bank of the Ket River, along which, as indicated by written sources, the old winter route from the village of Togur to Yenisei Governorate ran (Pelikh, 1981: 65).

Several elevations are also marked in the southern part of the “Draft”. One of these was designated with a yellowbrown band on the promontory section of the island formed by the Togur Ket River and the Togur channel of the Ket (see Figure , No. 6). From the geomorphologic point of view, remnants of terrace II above the floodplain, which were not flooded in spring, were located there. The presence of high places in the area in the upper mouth of the Ket River has been known since the first half of the 17th century, when building a fort on the “division” of the Ket River was discussed, which was supposed to replace forts Narym and Ket: high areas suitable for building fortifications and for agriculture were reported (Miller, 2005: 428).

An extended elevation on the left bank of the Ket River was marked, not by a continuous band, but by separate yellow-brown segments, bounded by the valleys of its left tributaries (see Figure, No. 7). This high place begins at the upper, “Togur” mouth of the Ket River, practically opposite the positive topographic element described above. In the area of Fort Ket, it forms a kind of promontory. Field studies at the location of this settlement have confirmed that it occupied an elongated promontory with high steep banks. From Fort Ket, the band denoting a high place stretches along the left bank, parallel to the channel of the Ket River, to Nyanzhin indigenous volost. It becomes interrupted in this place and continues beyond the “Outechya” River, located 10 days from Fort Ket. It is probably the Utka River, at the mouth of which the village of Stepanovka is currently located. Behind the “Outechya” River, the band is much thinner than in the estuarine part of the Ket River, which probably means leveling of the elevation.

Travelers and scholars of the 17th–19th centuries often called the left bank of the lower Ket River kryazh (‘ridge’). For example, in the first detailed description of the river, N. Spathari reported: “And they went from that Filkin yar through Angina channel, and there is an Ob kryazh on that Angina channel. There is also a two-hour trip through that channel for 2 versts. And that channel is on the right side of the Ket River [N. Spathari was traveling up the river and mentioned the banks along his way. – the Authors ]. Kryazh is on the right side of the channel. <…> And Fort Ket stands in a beautiful place, on the same kryazh , on the right side of the Ket” (Puteshestviye…, 1882: 73). In the Dictionary of Vladimir Dal, “kryazh” means continent; solid separate part of something, constituting a whole in itself; dry, unplowed place, strip; “materik”—a virgin layer of earth’s surface, ridge, natural, not filled-up, not alluvial (1994: 533, 795). On modern maps, there is a place called Belsky Kryazh in the interfluve of the Ket, Ob, and Chulym Rivers. Fragments of watershed plateau and high floodplain terraces, which break off in steep outcrops, come close to the riverbed on this segment of the Ket River. The kryazh stretches along the river for dozens of kilometers. As already mentioned, the old winter route from the village of Togur through Tainye yurts to Orlyukov yurts and further to Yenisei Governorate ran along the left bank of the Ket River (Pelikh, 1981: 65).

Analysis of the settlement system in the Ket River basin in the 17th–19th centuries shows that Russian villages emerged in the region, with rare exceptions, in the area along the left bank of the river in its lower reaches, approximately to its tributary, the Peteiga River. There were several dozens of Russian villages and hamlets there, which constituted Ket Volost in the 19th century (Karta Tomskogo okruga…, 1890). The designation of an elevation by Remezov precisely at this segment of the Ket River could have resulted from the location of the “kryazh” in that area, where the Russian villages were. They were marked on the “Draft”, although some remained unnamed. At the time the map was created, there were lands suitable for arable farming in that area, which is confirmed by numerous written sources about the agricultural occupations of the population living on the Ket River in the 17th–19th centuries. This is clearly demonstrated by the maps of the late 19th–early 20th centuries, where significant areas of arable land and gardens were marked on the left bank of the estuarine part of the Ket River (Karta naselennykh mest…, 1914). In the first quarter of the 20th century, scholars pointed to specific features of the “Ket Kryazh”. V.Y. Nagnibeda determined its borders from the Tainye yurts to the village of Chernaya and Paidugin yurts. The economy of the local population was based on agriculture, as well as hunting and fishing (Nagnibeda, 1920: 37). Apparently, by the late 17th century, the area was already known as a place meeting the needs of peasant economy and suitable for agriculture.

Conclusions

Analysis of conventions denoting elevations on the “Draft” makes it possible to argue about the objectivity and validity of their designation. They reflected real natural and geographical features of the territory, which were of practical importance for the local population. These elevations were known long before the compilation of topographic maps with contour lines. These elements of terrain were described by travelers and explorers of Siberia of the 17th–19th centuries, and were mentioned in the legends of the local population.

Thus, “mountain(s)” and “kryazhes” on the “Draft of the Land of Fort Narym” are not an “empty” illustration. Serviceman S.U. Remezov was fulfilling a government task, and displayed real elements of terrain, practically useful in land development, which is supported by the analysis of the current natural and geographical situation, as well as written records.

Acknowledgments

This study was a part of the State Assignment FWZG-2022-0005 “Study of Archaeological and Ethnographic Sites in Siberia in the Period of the Russian State”.

Список литературы “Mountains” on the draft of the land of fort Narym by S.U. Remezov

- Andreev A.I. 1940 Trudy Semena Remezova po geografi i i etnografi i Sibiri XVII–XVIII vv. In Problemy istochnikovedeniya, iss. 3. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 61–85.

- Barkov V.V. 1951 Materialy k geomorfologii reki Tyma. In Voprosy geografi i Sibiri, bk. 2. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 177–194.

- Chernaya M.P. 2002 Tomskiy kreml serediny XVII–XVIII v.: Problemy rekonstruktsii i istoricheskoy interpretatsii. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ. Chertyozhnaya kniga Sibiri, sostavlennaya tobolskim synom boyarskim Semenom Remezovym v 1701 godu. 1882 St. Petersburg: [Tip. A.M. Kotomina i Ko].

- Chindina L.A., Yakovlev Y.A., Ozheredov Y.I. 1990 Arkheologicheskaya karta Tomskoy oblasti, vol. 1. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Dal V. 1994 Tolkoviy slovar zhivogo velikorusskogo yazyka, vol. 2. Moscow: Progress–Univers.

- Donner K. 2008 U samoyedov v Sibiri, A.V. Baidak (trans.). Tomsk: Veter.

- Goldenberg L.A. 1990 Izograf zemli Sibirskoy: Zhizn i trudy S. Remezova. Magadan: Kn. izd.

- Grigor G.G. 1951 Obshchiy fi ziko-geografi cheskiy obzor Tomskoy oblasti i osobennosti yeyo yuzhnykh rayonov. In Voprosy geografi i Sibiri, bk. 2. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 157–176.

- Grigorovsky N.P. 1884 Opisaniye Vasyuganskoy tundry. In Zapiski ZSOIRGO, bk. VI. Omsk: [Tip. okruzhnogo shtaba], pp. 1–68.

- Karta naselennykh mest Narymskogo kraya Tomskoy gubernii, po dannym statistikoekonomicheskogo izsledovaniya, proizvedennogo Tomskim pereselencheskim rayonom v 1910–1911 gg. 1914 Tomsk: Tom. pereselen. rayon.

- Karta reki Vasyugan. 1982 Ot seleniya Katylga do ustya. Moscow: CKF VMF. Karta Tomskogo okruga Tomskoy gubernii. 1890 I. Zaitsev. Tomsk: Kartograf. zavedeniye A. Ilyina.

- Kontev A.V. 2022 Verkhneye Priobye i Priirtyshye na starinnykh kartakh (XVI–XVII vv.). Barnaul: Alt. Gos. Ped. Univ.

- Kostrov N. 1872 Narymskiy kray. Tomsk: [Tip. Gubern. pravleniya].

- Matveev A.V. 2009 Pritarye i severo-zapadnaya Baraba v “Khorografi cheskoy chertyozhnoy knige Sibiri” S.U. Remezova 1697–1711 gg. In Etnografo-arkheologicheskiye kompleksy: Problemy kultury i sotsiuma. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 132–138.

- Miller G.F. 2005 Istoriya Sibiri, vol. 1. [3rd edition]. Moscow: Vost. lit. Nagnibeda V.Y. 1920 Tomskaya guberniya: Statisticheskiy ocherk, iss. 1. [2nd edition]. Tomsk: [Nar. tip. No. 3].

- Okladnaya kniga Sibiri 1697 goda. 2015 Moscow: Istor. muzey.

- Pelikh G.I. 1981 Selkupy XVII veka (ocherki sotsialno-ekonomicheskoy istorii). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Plotnikov A.F. 1901 Narymskiy krai (5 stan Tomskogo uyezda, Tomskoy gubernii): Istoriko-statisticheskiy ocherk. St. Petersburg: [Tip. V.F. Kirshbauma].

- Priroda i ekonomika Aleksandrovskogo neftenosnogo rayona (Tomskaya oblast). 1968 A.A. Zemtsov (ed.). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ. Puteshestviye cherez Sibir ot Tobolska do Nerchinska i granits Kitaya russkogo poslannika Nikolaya Spafariya v 1675 godu: Dorozhniy dnevnik Spafariya s vvedeniyem i primechaniyami Y.V. Arsenieva. 1882 St. Petersburg: [Tip. V. Kirshbauma].

- Shostakovich B.P. 1877 Poyezdka po rekam Vasyuganu i Chizhapke v 1876 godu. Tomsk: [Gub. tip.]. Sibir XVIII veka v putevykh opisaniyakh

- G.F. Millera. 1996 Novosibirsk: Sib. khronograf. Sredniy Vasyugan – 300 let: Istoricheskiy ocherk. 2000 V.P. Zinoviev (ed.). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Tikhonov S.S. 2013 Karty S.U. Remezova v arkheologo-etnograficheskikh issledovaniyakh. Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Istoriya, No. 3: 52–56.

- Umansky A.P. 1996 Chertezhi Tomskogo i Kuznetskogo uyezdov S.U. Remezova kak istochnik po istorii Verkhnego Priobya. In Aktualniye problemy sibirskoy arkheologii. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 100–104.

- Yakovlev Y.A. 1994 Mogilniki dorusskogo naseleniya XVIII – nachala XX vv. Na territorii Tomskoy oblasti. Trudy Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo obyedinennogo istoriko-arkhitekturnogo muzeya, vol. VII: 28–54.