National park visitor segments and their interest in rural tourism services and intention to revisit

Автор: Sievnen Tuija, Neuvonen Marjo, Pouta Eija

Журнал: Вестник Ассоциации вузов туризма и сервиса @vestnik-rguts

Рубрика: Актуальные зарубежные исследования в сфере туризма

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.9, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The study aims to understand national park visitors’ interests to use tourism services provided in the vicinity of Linnansaari, Seitseminen and Repovesi national parks in Southern Finland. Separate visitor groups were identified based on their use of tourism services and their intention to revisit the area. Data were generated from a questionnaire survey of 736 visitors to the national parks. The analyses revealed five dimensions of interest in tourism services from which five visitor groups were identified: Countryside and outdoor friends, who were inter-ested in recreation services; safari riders, interested in renting snowmobiles and similar services; guided visitors, who were interested in guided tours; roomand rental seekers, whose main interest was accommodation and rental services, and uninterested, who had no interest in services. The strongest intentions to revisit the parks and the regions were recorded among “country-side and outdoor friends” and “safari riders”. The results of this study may help tourism enterprises, municipal-ity decision makers and park managers in rural communities surrounding national parks to understand and recognize visitors’ overall needs of tourism services.

Nature-based tourism, visitor, visitor segmentation, factor analysis, clustering

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140209443

IDR: 140209443 | УДК: 502.211 | DOI: 10.1273712533

Текст научной статьи National park visitor segments and their interest in rural tourism services and intention to revisit

In many rural communities, where agriculture and forestry have declined markedly as the principal livelihoods, nature tourism may offer alternative economic opportunities (e.g. Cordell, Bergstrom, & Watson, 1992; Eagles, 2004; Eagles & McCool, 2002; Goodwin & Dilys, 2001;

A national park as a destination is a package of attractions, such as nature, culture, and tourism services. It is composed of a number of attributes that together determine the attractiveness of the travel destination to a particular tourist (Hong-Bumm, 1998).

National parks are considered as a potential attraction for tourism, which may sustain livelihoods and reinvigorate small economies in many rural and peripheral regions (Haukeland, Grue, & Veisten, 2010; Lundmark, Fredman, & Sandell, 2010; Mach-lis & Field, 2000;

Studies have shown that previous visitors form an important part of the future visitor flow (Sparks, 2007; Sonmez & Graefe, 1998). Furthermore, loyalty to a tourism destination has been found to be associated with higher visit motivation, particularly travel push motivations such as relaxation, family togetherness, safety and fun and satisfaction (Yoon & Uysal, 2005). Other factors explaining revisit intention include place attachment, product characteristics, perceived quality of services, social bonds, subjective norms, and attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Huang & Hsu, 2009; Lam & Hsu, 2006; Neuvonen, Pouta, & Sievanen, 2010; Vassiliadis, 2008). These factors seemed to directly and indirectly affect the decisionmaking process when a visitor chooses to revisit a national park. Less attention has been paid to how tourists and visitors may differ in their demand for tourism services at the destination and whether this is related to their intention to revisit. Understanding the comprehensive visit experience from a tourist’s point of view, including both the park attractions and the services available in the surrounding region, may help tourism enterprises and municipal decision makers in rural communities to ensure that their services and products fulfill the needs of park visitors.

In order to develop tourism services that are in balance with the needs of national park visitors, it is important to be aware of the whole range of interests and motivations among this segment of rural tourists. In the literature, tourists and visitors have been segmented based on travel motivations or benefits (Frochot, 2005; Galloway, 2002; Molera & Albaladejo, 2007; Park & Yoon, 2009), satisfaction and consumptionrelated emotions (Bigne & Andreu, 2004), activity (Mehmetoglu, 2007), and visit motivations (Beh & Bruyere, 2007). However, a few studies have focused on segmenting tourists based on their interest in using facilities or purchasing goods or services (Burge & Resnick, 2000; Haukeland, Grue, & Veisten, 2010;

The aim of the present study is to produce knowledge concerning the service demands of national park visitors. The study determines whether separate visitor groups can be identified based on their actual use of and interest in using various tourism services. Whether these possible visitor segments differ in their intention to revisit the park or the surrounding rural region is also analyzed. The profiles of visitor segments are made with variables concerning socio-demographic background, visitation history, satisfaction with services and attitudes towards the countryside in general. Finally, the study evaluates the potential of these visitor segments to bring income to the park regions.

Literature Review

Tourism Services and the Motivation of Tourists to visit a National Park and the Surrounding Countryside

Tourism is a system that involves both demand and supply components. Actions on both sides influ- ence the decision of a potential tourist on where to travel (Gunn, 2002). A national park in a rural community is often the main attraction for visitors to that community. Gunn (2002) emphasized that all actors related to tourism, including national parks as an example of government agencies, should understand travel market preferences and develop the supply of tourism services. This supply concerns both natural and man-made resources related to tourism. National park managers themselves need to have a full understanding of travel market interests and needs (Gunn, 2002). In addition, tourism service providers should have “a full understanding” of the needs and interests among national park visitors to be able to provide services and products that appeal to this segment of tourists.

The push and pull model is often used to conceptualize tourist motivation (Crompton, 1979). This views the travel decision as a result of two forces: The push factor explains a person’s need to leave home every now and then; and the pull factor explains the attraction of the place “away from home”. The focus of the present study is the pull factors related to a combination of the physical (natural) environment and conditions and the supply of services. The supply of recreational services, such as visitor centers, marked hiking routes, nature trails and campfire sites, is a part of the image of Finnish national parks

(Metsahallitus, 2011b). Bansal and Eiselt (2004) suggest that the image of a region is one of the three components that play the main role in travel planning and the intention to visit a destination, together with motivation and travel companions. According to Tapachai and Waryszak (2000), the image of a destination is a function of five characteristics: Functional, social, emotional, epistemic and conditional. The functional value, which is the focus in this study, refers to the perceived utility, e.g. the ability to perform functional, utilitarian or physical acts (shopping, food choices, safety, and the nature of the landscape).

Travel satisfaction has generally been used as an assessment tool for the evaluation of travel experiences (Bramwell, 1998; Ross, & Iso-Ahola, 1991). Travel satisfaction is a positive perception or feeling, or an expressed degree of pleasure that tourists gain from a visit (Beard & Ragheb, 1980). Satisfaction with the services and their quality is a function of the difference between expectations and perceived reality (e.g. Baker & Crompton, 2000; Bigne, Sanchez, & Sanchez, 2001; Cai, Wu, & Bai, 2004; Lee, Graefe, & Burns, 2007; Ross & Iso-Ahola, 1991; Tian-Cole & Cromption, 2003; Um, Chon, & Ro, 2006; Yoon & Uysal, 2005). Previous research has indicated that both a high perceived service quality and high satisfaction make a return to nature tourism destinations more likely (Lee, 2006, 2009; Lee, Graefe, & Burns, 2007). Positive experiences of services, products and other resources provided by tourism destinations (positive destination image) could produce return visits, as well as other positive behaviors such as recommendations to friends and/or relatives (Beerli & Martin, 2004;

Segmentation

Market segmentation refers to the subdivision of a market into homogeneous subsets of customers, where any subset may conceivably be selected as a market target (Kotler, 1988). There are many different types of typologies and segmentations of tourists and visitors (Chen, Hwang, & Lee, 2006; Frochot, 2005; Haukeland et al., 2010; Kastenholz et al., 1999; Kerstetter, Hou, & Lin, 2004; Li, Cheng, Kim, & Petrick, 2008; Molera & Albaladejo, 2007;

Few studies have focused on the segmentation of tourists who visit nature-related or rural destinations. Galloway (2002) demonstrated that visitors to national parks differ as a group in their demands for and perceptions of services and their frequency of visits. Visitors belonging to a higher sensation-seeking group (i.e. people interested in physically demanding activities, risk taking, novel experiences and complex sensations) often visited national parks; they also appreciated services and facilities more than groups with more modest sensations. Kerstetter, Hou, and Lin (2004) examined tourists’motives and intended behavior (management, consumer behavior, and participating behavior), and identified three segments with differing intended behaviors.Abenefit-based or psychometric approach was used by Frochot (2005) who identified rural tourist segments according to the benefits gained or motivations expressed when visiting the countryside.

Segmentation according to visit motivation was employed in a study of rural tourists by Park and Yoon (2009). They identified four visitor segments, of which one was named “family togetherness”, which was particularly interested in relaxing in nature and visiting recreational forests or historic sites. The other three groups were also interested in agricultural and rural life experiences, but not particularly in nature-related activities.

The literature has paid little attention to the association between the interest in using different types of tourism services and the intention to revisit a park or the surrounding region. The issue has been considered from viewpoints such as interest in different types of activity (Kemperman, Chang-Hyeon, & Timmermans, 2004; Lau & McKercher, 2004; Li, Cheng, Kim, & Petrick, 2008) or destination perceptions or products (McKercher & Wong, 2004; Vassili-adis, 2008). Thus, the present study provides further information on this association, i.e. how national park visitor segments based on interest in using tourism services differ in terms of their intention to revisit the park or the surrounding region.

Data and Methods

Case: Three National Parks in Southern Finland

Three national parks in Southern Finland, Lin-nansaari, Seitseminen and Repovesi, were selected as case parks for this study, based on a pilot study covering all national parks in Finland (Selby et al., 2007). The selection criteria were their differences in natural characteristics, time since establishment and location in rural region. Linnansaari National Park is located in the middle of a large lake area in Eastern Finland. The natural landscape in Seitseminen National Park is forest dominated, whereas the third study area, Re-povesi National park, is surrounded by several small lakes and bold cliffs. Linnansaari was established in 1956, Seitseminen in 1982 and Repovesi in 2003. Linnansaari and Seitseminen parks provide a moderate standard of park services, e.g. visitor centers, trails and camping sites with camp-fire sites, while Repove-si has no visitor center and thus has a lower standard of services (Selby et al., 2007). In 2008, there were 44,500 visits to Seitseminen National Park, 29,000 to Linnansaari National Park and 75,500 to Repovesi National Park (Metsahallitus, 2009b).

Visitors to Seitseminen National Park mainly come from neighboring regions, and the park is the only destination for 62% of visitors (Pulkkinen & Valta, 2008). Linnansaari National Park attracts more national visitors, and it was the only destination for 45% of visitors (Tunturi, 2008). Most visits to Repovesi National Park are by people from the neighboring regions (26%) and from the Helsinki metropolitan (capital) area (19%) (Hemmila, 2008). The majority of the visitors (79%) to Repovesi reported that the national park was the only or main destination for the trip (Hemmila, 2008). The proportion of all visitors staying overnight varied between 32 and 76% in the case parks (Hemmila, 2008; Pulkkinen & Valta, 2008; Tunturi, 2008). The most important motives for visiting Seitseminen, Linnansaari and Repovesi national parks were related to experiencing and becoming familiar with the natural environment and the park, personal relaxation and mental well-being, getting away from noise and pollution, and also being with family or friends (Hemmila, 2008; Pulkkinen & Valta, 2008; Tunturi, 2008).

Data Collection

The empirical data were collected from Seit-seminen and Linnansaari National Parks in 2006 and from Repovesi in 2007. The sampling season was from mid-May until the beginning of October. Altogether, 736 respondents returned the questionnaire, and the response rate was 72% in Seitseminen, 63% in Linnansaari and 68% in Repovesi National Park. The survey was conducted on-site in the parks by Metsahallitus. The visitor surveys employed the method developed by Erkkonen and Sievanen (2002), which aims to randomize the respondents. The data was collected from the park visitors at several entrance points and some other locations inside the park seven days a week and at different times of day. The sessions of data collection on selected sites varied randomly over the entire season. All Finnish visitors within the data collection time slot entering the site were asked to participate and asked to return the questionnaire using a postage paid envelope. A map was provided to inform respondents about the boundary of the park area and the boundary of the surrounding countryside that was chosen to represent the local community in the study. The non-respondence of onsite surveys is difficult to assess, because the total number of visitors is unknown. In Seitseminen National Park, about 36% of visitors, who were invited to participate, refused to fill the questionnaire (Tunturi, 2008). Data of all three national parks were merged into one dataset for the analysis, as the pretesting phase of the analysis showed that similar segmentation profiles were found in all three parks.

Variables

The study necessitated measurement of actual use as well as potential interest in using different tourism services. Thirty-seven services were measured, including guided excursions, equipment rental, the rental of a sauna, the renting of different types of accommodation, and possibilities to visit a farm and to participate in farm activities. All the services and activity opportunities were provided in each of the regions in question. The use of services was measured with a dichotomous variable and coded as 3 (yes) or 0 (no) to give it more weight in the subsequent analysis. The future intention to use the services was measured with a three-scale variable and coded as 2 (yes), 1 (possibly) or 0 (no). From these components of actual use and future intention to use, a sum variable was constructed to indicate interest in using tourism services on a scale from 1–5. The highest score (5) was given to those who had both used the service and were interested in using it again in the future, and the lowest score to those who did not use it in the past and were not interested in using it. The intention to revisit the park and the region was measured with a three-point scale. Information on attitudes towards the countryside, the perceived quality of rural tourism services, and social bonds to the area were also collected. Visitors to a national park may have social ties to the region because of family or relatives, or recreational home ownership. Socio-economic background variables, such as gender, age and household income were measured in order to profile the visitor groups.

Statistical Analyses

Factor and cluster analysis were employed to construct visitor segments. Factor analysis (maximum likelihood extraction and varimax rotation) was used to identify those services for which actual use and future interest in using them most strongly correlated with each other. To clarify the interpretation of the factor analysis, only those services were accepted whose loadings were. .400. This meant that 23 items from the original 37 were used to identify different dimensions of interest. The removed items were commonly loaded on all dimensions, which disturbed the interpretation. The number of factors was based on an Eigenvalue of over 1.00. Cronbach’s alpha was used to estimate the internal consistency and reliability of a set of measures. Cronbach’s alphas (all. .7) indicated acceptable consistency of service measures used for factor interpretation. Each factor represented an interest dimension.

Based on the calculated factor scores, two-step cluster analysiswas used to produce visitor groups that differed according to the identified interest dimensions. The number of groups was determined by the clarity of the interpretation. To compare the visitor groups in terms of revisit intention, countryside attitudes, socio-demographic variables and some other exploratory variables, analysis of variance and the Chi-squared test were used.

Results

Almost half of the visitors to Linnansaari, Seit-seminen and Repovesi National Parks reported that visiting the national park was the main reason for their trip. More than half of the visitors reported that their social contact with local people only occurred as a results of using local tourism services. Many visitors to the national parks had some form of regular contact with the region: 41% had relatives or friends living in the region, others had regular access to a rec- reational home nearby (20%) or some other interest such as a special outdoor or cultural activity to pursue in the park or in the region (7%). On average, visitors used two of the services provided in the surrounding countryside on their visit and were interested in using eight services in the future indicating the existing interest potential. The services that were of most interest were restaurants and cafes, renting sauna, purchases from farm shops, and renting canoes and self-guided canoe trips.

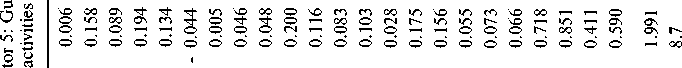

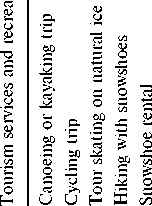

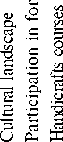

The initial analysis focused on defining possible groups of services that interested individual visitors. As a result of the factor analysis, five dimensions of tourism services of interest were identified: (a) outdoor activities, (b) countryside, (c) safaris, (d) room and rentals, and (e) guided activities (Table 1). The first dimension, outdoor activities, represented interests related to services and opportunities that support special outdoor activities such as canoeing, bicycling, long-distance ice-skating, snowshoe walking and cross-country horseback riding. This dimension also received strong loadings related to the renting of equipment for these activities. The factor explained 11.9% of the rotated factor model. The second dimension (11.5%) expressed interest in countryside activities, such as farm and forest work, and learning about traditional skills and crafts. The third dimension (9.4%) represented interests in renting a snowmobile or in guided safaris either by snowmobile or off-road vehicles. The fourth dimension (9.2%), room and rentals, gathered interest in purchasing mainly accommodation services together with interest in renting equipment for boating and hiking, which are common outdoor activities related to renting a cottage. The last dimension (8.7%), guided activities, expressed visitors’ interests in participating in guided excursions related to hiking, nature studies and mushroom picking.

The national park visitors were divided into groups by cluster analysis based on these five dimensions of interest in using tourism services. The analysis produced five visitor groups that were named according to their service interest: (i) Countryside and outdoor friends consisted of visitors who were interested in services such as equipment rentals, recreation facilities and opportunities to visit a farm, to participate in forest work etc.

The group accounted for 23% of the visitors; (ii) Safari riders were visitors whose interest was in tours with snowmobile or off-road vehicle. This group accounted for 25% of the visitors; (iii) Guided visitors (5%) were visitors interested in guided hiking, na- ture study etc., excursions, and (iv) room and rental seekers (18%) were the visitors interested in boat and cottage rentals, as well as bed and breakfast services; finally, (v) uninterested were visitors who were not interested in any commercial services. This group was the largest and accounted for 29% of the visitors (Table 2).

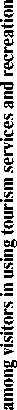

The intention to revisit the park, as well as that to revisit the region, differed significantly between groups (Table 3). Groups who were interested in safaris, or in countryside and outdoor activities, had a fairly high interest in revisiting the park and the region. Among these groups, 20–24% of visitors were interested in revisiting the region because of access to a recreational home. According to the number of previous visits to the park, the most regular visitors were those who were interested in the countryside and outdoor life, and those who were uninterested in tourism services. These less service-oriented visitors had visited the park in the last five years as often as the group countryside and outdoor friends . The room and rental seekers mainly emphasized the need for rental services and accommodation, but they were not particularly interested in nature or outdoor life-related services. This group expressed the least interest in revisiting either the park or the region. However, there was wide variation within the group, as 21% also had access to a recreational home in the region. In the safaris group, almost one in four had access to a recreational home in the region, while in the uninterested group only 8% reported having an opportunity to use a recreational home in the region. The visitors belonging to the guided visitors group came to the park as members of a larger group (e.g. as part of an organized tour), which may explain their interest in guided services. No significant differences were found between the groups according to the length of stay. In all groups, more than half of the visitors stayed overnight in the park or in the surrounding countryside.

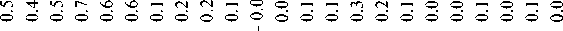

When profiling visitor groups, differences were found in visitors’ attitudes towards the countryside. Visitors who expressed the most positive attitude towards the countryside belonged to the guided visitors and countryside and outdoor friends groups (Table 4). All five visitor groups had rather similar views of the quality of tourism services in the countryside surrounding the national park.

The groups differed significantly in terms of their socio-demographic backgrounds (Table 5). Visitors in the uninterested group were, on average, older than the countryside and outdoor friends and safari riders. More than half of the visitors were female in the countryside and outdoor friends group, where- as the safari riders and guided visitors groups were more male-dominated. The safari riders group had the highest and the countryside and outdoor friends group the lowest household income.

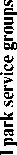

The potential of each group to bring income to the region depends on their use of services and expenditure at the destination. The guided visitors were the most service use-oriented based on the absolute number of services they used and intended to use, but those in the countryside and outdoor friends group were also active serviceusers (Table 6). The safari riders group was almost as low in the actual use of services as the uninterested group, but considerably more interested in future use. These figures are somewhat contradictory with the personal travel expenses of the visitors. The trip expenses were highest among room and rental seekers , but the group had fairly low interest in the future use of services. Although the differences between groups in expenses were considerable, they were not statistically significant because of the wide variation within the groups. The total expenses also included purchases outside the study area, and therefore the result was only indicative.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study segmented national park visitors based on their interests in using tourism services in the surrounding rural communities. The visitor segmentation provides an approach for planning the tourism service provision in rural areas, which is essential to the tourism enterprises to keep their business running and to offer more job opportunities. Segmentation based on the interest of tourists in purchasing goods and services has previously been applied to national park visitors only to a limited extent (Burge & Resnick, 2000; Haukeland, Grue, & Veisten, 2010;

The results demonstrated the park visitors’ multifarious interests in different tourism services, and five

л

.# с

^ я S. ф

С

(/)

с

| о S.

^ О Г- m m г-.| ^. О ^ -^ ^ •^ '/'i ^ О', Г- П Г- О ▻- Г- Г- Г--0\сччо'ОГ-ОхЬ^^чо£9хЬс^О\с^со^О\сос^сочох|-

О

,5й

е

О

m

m

Й о 1

Й

S

,0й

'S

о

^

Table 2.

Visitor groups based on cluster analysis of service factor scores.

|

%of |

Factor 1: Outdoor |

Factor 2: Country- |

Factor 3: |

Factor 4: Room & |

Factor 5: Guided |

|

|

Groups |

visitors |

activities |

side |

Safaris |

rentals |

activities |

|

Factor score: mean (standard error) |

||||||

|

Countryside and |

23 |

0.681 |

0.785 |

- 0.685 |

- 0.073 |

- 0.025 |

|

outdoor friends |

(0.085) |

(0.092) |

(0.027) |

(0.068) |

(0.066) |

|

|

Safari riders |

25 |

0.195 (0.074) |

0.063 (0.088) |

1.434 (0.067) |

- 0.028 (0.061) |

- 0.040 (0.131) |

|

Guided visitors |

5 |

0.080 (0.178) |

- 0.264 (0.177) |

0.060 (0.214) |

0.176 (0.261) |

2.751 (0.131) |

|

Room and rental seekers |

18 |

- 0.300 (0.063) |

- 0.329 (0.056) |

- 0.438 (0.034) |

1.052 (0.081) |

- 0.318 (0.060) |

|

Uninterested |

29 |

- 0.533 (0.032) |

- 0.430 (0.017) |

- 0.404 (0.007) |

- 0.584 (0.020) |

- 0.218 (0.047) |

|

F-test |

53.71 |

49.26 |

380.36 |

84.91 |

142.59 |

|

|

p-value N = 585 |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

< 0.0001 |

|

Table 3.

Park visitation: past and present visits and future intention to revisit to the park and the surrounding rural area, access to a recreational home and overnight stays in the region (recreational home or other), COFјCountry-side and outdoor friends, SRјSafari riders, GVјGuided visitors, RRSјRoom and rental seekers, UјUninterested.

|

V ariables |

COF |

SR |

GV |

RRS |

U |

|

|

Intention to visit in future |

||||||

|

The park, % of visitors |

70 |

75 |

61 |

58 |

68 |

8.928 (0.063) (1 |

|

The region surrounding the Park, %of visitors |

73 |

65 |

58 |

48 |

61 |

16.20 (0.003) (1 |

|

Past visitation and bonds |

||||||

|

Access to recreational home in region, %of visitors |

20 |

24 |

14 |

21 |

8 |

11.71 (0.020) (1 |

|

Number of visits to the park (5 years), mean |

12 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

12 |

0.890 (0.470) (2 |

|

Characteristics of the present visit |

||||||

|

Size of the group, mean |

4 A |

5 A |

12 B |

4 A |

5 A |

5.088 (< 0.001) (2 |

|

Length of stay (hours, day visitors), mean |

5.0 |

6.7 |

4.5 |

6.2 |

5.1 |

0.567 (0.687) (2 |

|

Length of stay (days, overnight visitors), mean |

2.6 |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

0.353 (0.841) (2 |

|

Stayed overnight in the region, %of visitors |

69 |

64 |

59 |

70 |

61 |

3.968 (0.410) (1 |

(1 Chi-squared test (p-value).

(2 F-test (p-value); different symbols A and B indicate that the groups differ from each other statistically signi fi cantly based on Tukey’s test

|

Table 4. Visitors’ attitudes towards the countryside and satisfaction with the quality of national park services, COFјCountry-side and outdoor friends, SRјSafari riders, GVјGuided visitors, RRSјRoom and rental seekers, UјUninterested. Variables COF SR GV RRSU Attitude towards the 53AB 52 AB 56 A 51B 52 AB 2.436 countryside (sum (0.046)(2 index), mean Perceived quality of 45 43 48 43 42 1.575 tourism services, (0.180)(2 landscape, environment and local hospitality, mean (2 F-test (p-value); different symbols Aand B indicate that the groups differ from each other statistically signi fi cantly based on Tukey’s test Table 5. Sociodemographics of the visitor groups, COFјCountry-side and outdoor friends, SRјSafari riders, GVјGuided visitors, RRSјRoom and rental seekers, UјUninterested. Variables COF SR GV RRSU Age (years), mean 41A 36 B 42 ABC 43 AC 47 C 11.96 (< 0.001)(2 Household income 5.9 A 6.9 B 6.4 AB 6.8 AB 6.4 AB 3.017 group, mean (0.018)(2 Female, %of 61 41 36 47 50 11.98 visitors (0.017)(1 (1 Chi-squared test (p-value).

Table 6. Potential of visitor groups as service users: used services and travel expenses, COFјCountry-side and outdoor friends, SRјSafari riders, GVјGuided visitors, RRSјRoom and rental seekers, UјUninterested. Variables COF SR GV RRS U Number of used tourism 2.0 A 1.5 AB 3.9 C 1.8 AB 1.3 B 14.724 services, mean (< 0.0001)(2 Number of tourism services 11.5 A 9.4 B 11.0 AB 7.1 C 2.8 D 50.176 intending to use, mean (< 0.0001)(2 Personal travel costs (total), 146 131 35 256 102 0.462 mean (3 (0.763)(2

|

|

|

98 |

научный журнал ВЕСТНИК АССОЦИАЦИИ ВУЗОВ ТУРИЗМА И СЕРВИСА 2015 / № 3 Том 9 |

different visitor groups were identified: Countryside and outdoor friends, safari riders, guided visitors, room and rental seekers, and uninterested . The study therefore supports the results of Haukeland, Grue and Veisten (2010), who found that visitors to national parks had varied motivations, and also that the visitors had varied expectations according to the facilities needed, as well as wishes for improvements of the existing facilities. Haukeland, Grue and Veisten (2010) identified dimensions of services and facilities that have counterparts in the dimensions of tourism service interests found here: The “track and signposts” dimension is comparative to “outdoor activities” (which reflect demand for recreation opportunities and related facilities); the “food and accommodation” dimension is comparable to “room and rentals”, and “tours and interpretation” is close to “guided activities”. The group of visitors in the present study that was not interested in any particular services dimension seems to have a counterpart in Haukeland, Grue and Veisten’s (2010) segment that has little interest in developed services and facilities. However, there are many differences in these two studies; first, Haukeland, Grue and Veisten (2010) studied foreign tourists, and the present study data consists mainly of domestic tourists. Second, their study was also more focused on national park tourism per se, while this study was more focused on national park tourism in the context of rural tourism. Also, this study related the national park visitor segments to their intention to revisit the region, which improves the understanding of how service satisfaction and service interests affect the visitation in national parks as well as in surrounding communities.

The study provides a picture of national park visitors by examining the association between visitor groups segmented according to their multifaceted interests in tourism services, and their intention to revisit the park and surrounding region. Past behavior is a strong predictor of visit intentions in general (Huang & Hsu, 2009; So"nmez & Graefe, 1998; Sparks, 2007), but the overall attachment to a place has also appeared to be an effective predictor of revisit intention (Hailu, Boxall, &McFarlane, 2005; Neuvonen, Pouta,&Sieva"nen, 2010). Two of the visitor groups showed a stronger revisit intention than the other groups. They were countryside and outdoor friends and safari riders , whowere interested in both self-service recreation opportunities as well as renting equipment for outdoor activities, particularly for motorized safaris. Members of these groups are potentially frequent visitors to the region based on their social bonds and opportunity to use a recreation home. The results suggest that the potential market segment of recreation home visitors is not fully exploited yet in national park communities. A previous study of Finnish recreation home users also identified a potential group of visitors that are interested in purchasing tourism services (Sievanen, Pouta, & Neuvonen, 2007).

It is also important for park managers to consider different visitor groups according to their multifaceted interests to visit a park and the surrounding region, and to contribute to the tourist flow visiting rural communities. A national park can have a particular role in the process of local community development (Courtney, Hill,&Roberts, 2006;

More research is needed to identify the multifaceted interests of people visiting national parks and park communities, and the role of tourism service provision in that context. Furthermore, more research is needed to understand how different motivations and interests are related to national park visitation.

Список литературы National park visitor segments and their interest in rural tourism services and intention to revisit

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Aho, S., & Ilola, H. (2004). Maaseutu suomalaisten asenteissa, toiveissa ja kokemuksissa. Lapin yliopiston kauppatieteiden ja matkailun tiedekunnan julkaisuja . B. Tutkimusraportteja ja selvityksiä 2.

- Bansal, H., & Eiselt, H.A. (2004). Exploratory research of tourism motivations and planning. Tourism Management, 25, 387-396 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00135-3

- Baker, D.A., & Crompton, J.L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785-804 DOI: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

- Beard, J.G., & Ragheb, M.G. (1980). Measuring leisure satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 12(1), 20-33 DOI: 10.1177/004728758001900257

- Beerli, A., & Martın, J.D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657-681 DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

- Beh, A., & Bruyere, B.L. (2007). Segmentation by visitor motivation in three Kenyan national reserves. Tourism Management, 28(6), 1464-1471 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.01.010

- Bigné, J.E., & Andreu, L. (2004). Emotions in segmentation. An empirical study. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 682-696 DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.018

- Bigné, J.E., Sánchez, I.M., & Sánchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables, and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationships. Tourism Management, 22(6), 607-616 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00035-8

- Bramwell, B. (1998). User satisfaction and product development in urban tourism. Tourism Management, 19, 35-47 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00091-5

- Burge, J.F., & Resnick, B.P. (2000). Marketing and selling travel products (2nd ed., pp. 581-596). Albany, NY: Delmar/Thompson Learning.

- Cai, L.A., Wu, B.,&Bai, B. (2004).Destination image and loyalty. TourismReview International, 7(3), 153-162.

- Chen, H. -J., Hwang, S., & Lee, C. (2006). Visitor’s characteristics of guided interpretation tours. Journal of Business Re-search, 59, 1167-1181 DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.006

- Cordell, H.K., Bergstrom, J.C., & Watson, A.E. (1992). Economic growth and interdependence effects of state park visitation in local and state economics. Journal of Leisure Research, 24, 253-268.

- Courtney, P., Hill, G., & Roberts, D. (2006). The role of natural heritage in rural development: An analysis of economic link-ages in Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 22, 469-484. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.02.003.

- Crompton, J. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408-424 DOI: 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5

- Eagles, P.F.J. (2004). Trends affecting tourism in protected areas. In T. Sievänen, J. Erkkonen, J. Jokimäki, J. Saarinen, S. Tuulentie, & E. Virtanen (Eds.), Policies, methods and tools for visitor management. Proceedings of the 2nd Interna-tional Conference on Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas. June 1620, 2004. Rovaniemi, Finland (p. 1725), Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute 2. Available at: http://www.metla.fi/julkaisut/workingpapers/2004/mwp002.htm.

- Eagles, P.F.J., & McCool, S. (2002). Tourism in national parks and protected areas: Planning and management. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing, 336 pp.

- Erkkonen, J., & Sievänen, T. 2002. Standardisation of visitor surveys. Experiences from Finland. In A. Arnberger, C. Bran-denburg, & A. Muhar (Eds.). Monitoring and management of visitor flows in recreational and protected areas. January 30-February 2, 2002, Vienna Austria. MMVConference proceedings. Bodenkultur University Vienna, pp. 252-257.

- Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourist motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 555-581 DOI: 10.1016/0160-7383(94)90120-1

- Fortin, M.-J., & Gagnon, C. (1999). An assessment of social impacts of national parks on communalities in Quebec, Canada. Environmental Conservation, 26(3), 200-211 DOI: 10.1017/S0376892999000284

- Frochot, I. (2005). A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: A Scottish perspective. Tourism Management, 26, 335-346 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.016

- Galloway, G. (2002). Psychographic segmentation of park visitor markets: Evidence for the utility of sensation seeking. Tour-ism Management, 23, 581-596 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00025-0

- Goodwin, H., & Dilys, R. (2001). Tourism, livelihoods and protected areas: Opportunities for fair-trade tourism in and around National parks. International Journal of Tourism Research, 3(5), 377-391, DOI: 10.1002/jtr.350

- Goeldner, C.R., & Ritchie, J.R.B. (2009). Tourism: Principles, practices, philosophies, (11th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 624 pp.

- Gunn, C.A. (2002). Tourism planning. Basics, concepts, cases (4th ed.). New York and London: Routledge, 442 pp.

- Hailu, G., Boxall, P.C., & McFarlane, B.L. (2005). The influence of place attachment on recreation demand. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(4), 581-598 DOI: 10.1016/j.joep.2004.11.003

- Harju-Autti, A. (2010). Matkailun yleisosa. TEM: n ja ELY-keskusten julkaisu. Toimialaraportti 9/2010. . 69 pp.

- Haukeland, J.V., Grue, B., & Veisten, K. (2010). Turning national parks into tourist attractions: Nature orientation and quest for facilities. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(3), 248-271 DOI: 10.1080/15022250.2010.502367

- Hemmilä, T. (2008). Repoveden kansallispuiston kävijätutkimus 2007. . Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja, Sarja B, 101. 51 pp.

- Hong-Bumm, K. (1998). Perceived attractiveness of Korean destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 340-361 DOI: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00007-3

- Huang, S., & Hsu, C.H.C. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research, 48(29), 29-44 DOI: 10.1177/0047287508328793

- Kastenholz, E., Davis, D., & Paul, G. (1999). Segmenting tourism in rural areas: The case of North and Central Portugal. Journal of Travel Research, 37(4), 341-352 DOI: 10.1177/004728759903700405

- Kauppila, P. (1999). Matkailun taloudelliset vaikutukset Inarissa: Tunnuslukuja ja arviointia. . Nordia tiedonantoja 4/1999, 88-95.

- Kemperman, A.D.M., Chang-Hyeon, J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2004). Comparing first-time and repeat visitors’ activity pat-terns. Tourism Analysis, 8, 159-164.

- Kerstetter, D.L., Hou, J.-S., & Lin, C.-H. (2004). Profiling Taiwanese ecotourists using a behavioural approach. Tourism Management, 25, 491-498 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00119-5

- Kotler, P. (1988). Marketing management: Analysis, planning and control (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 792 pp.

- Lam, T., & Hsu, C.H.C. (2006). Predicting behavioural intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management, 27, 589-599 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.003

- Lau, A.L. S., & McKercher, B. (2004). Exploration versus acquisition: A comparison of first-time and repeat visitors. Journal of Travel Research, 42, 279-285 DOI: 10.1177/0047287503257502

- Lee, T.H. (2009). A structural model to examine how destination image, attitude, and motivation affect the future behaviour of tourists. Leisure Sciences, 31(3), 215-236 DOI: 10.1080/01490400902837787

- Lee, T.H. (2006). Assessing a river tracing behavioural model: A Taiwan example. Anatolia, 17(2), 322-328 DOI: 10.1080/13032917.2006.9687194

- Lee, J., Graefe, A.R., & Burns, R.C. (2007). Examining the antecedents of destination loyalty in a forest setting. Leisure Sci-ences, 29(5), 463-481 DOI: 10.1080/01490400701544634

- Li, X., Cheng, C.-K., Kim, H., & Petrick, J.F. (2008). A systematic comparison of first-time and repeat visitors via a two-phase online survey. Tourism Management, 29, 278-293. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.010.

- Lundmark, L.J.T., Fredman, P., & Sandell, K. (2010). National parks and protected areas and the role for employment in tourism and forest sectors: A Swedish case. Ecology and Society, 15(1), 19. Available at: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss1/art19/.

- Machlis, G.E., & Field, D.R. (2000). National parks and rural development. Practice and policy in the United States. Wash-ington, DC: Island Press, 323 pp.

- Manning, R.E. (2011). Studies in outdoor recreation. Search and research for satisfaction (3rd ed.). Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 468 pp.

- McKercher, B., & Wong, D.Y.Y. (2004). Understanding tourism behavior: Examining the combined effects of prior visitation history and destination status. Journal of Travel Research, 43, 171-179 DOI: 10.1177/0047287504268246

- Mehmetoglu, M. (2007). Typologising nature-based tourists by an activity -theoretical and practical implications. Tourism Management, 28, 651-660 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.02.006

- Metsähallitus. (2009a). Kansallispuistojen ja retkeilyalueiden kävijöiden rahankäytön paikallistaloudelliset vaikutukset . Metsähallitus, luontopalvelut. Report . Available at: http://www.metsa.fi/sivustot/metsa/fi/Eraasiatjaretkeily/Virkistyskaytonsuunnittelu/suojelualueidenmerkity-spaikallistaloudelle/Documents/Kavijoiden%20paikallistaloudelliset%20vaikutukset.pdf.

- Metsähallitus. (2009b). Metsähallitus’s data base system for visitor information (ASTA). .

- Metsähallitus. (2010). Financial statements and Annual report of Metsähallitus’ Business operations 31 Jan 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2011 from: http://www.metsa.fi/sivustot/metsa/en/WhatsNew/Publications/Documents/financial_state-ment_2011_eng.pdf

- Metsähallitus. (2011a). Sustainable nature tourism in protected areas. Retrieved June 29, 2011 from: www.metsa.fi/sustain-ablenaturetourism.

- Metsähallitus. (2011b). National parks. Retrieved June 29, 2011 from: http://www.outdoors.fi/DESTINATIONS/NA-TIONALPARKS.

- Mok, C., & Iverson, T.J. (2000). Expenditure-based segmentation: Taiwanese tourists to Guam. Tourism Management, 21, 299-305 DOI: 10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00060-6

- Molera, L., & Albaladejo, I.P. (2007). Profiling segments of tourists in rural areas of South-Eastern Spain. Tourism Manage-ment, 28, 757-767 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.05.006

- More, A.T., Stevens, T., Kuentzel, W., & Dustin, D. (2008). Changing demand for U.S. national parks: Causes and ethical implications for preservation. In M. Sipilä, L. Tyrväinen, & E. Virtanen (Eds.), Forest recreation & tourism serving urbanised societies. Joint Final Conference of Forest for Recreation and Tourism (COST E33) and 11th European Forim on Urban Forestry (EFUF), Hämeenlinna, Finland, 28.31.5.2008. Abstrcts, 69 pp.

- Neuvonen, M., Pouta, E., Puustinen, J., & Sievänen, T. (2010). Visits to national parks: Effects of park characteristics and spatial demand. Journal for Nature Conservation, 18(3), 224-229. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2009.10.003.

- Neuvonen, M., Pouta, E., & Sievänen, T. (2010). Intention to revisit a national park and its vicinity: Effect of place attachment and quality perceptions. International Journal of Sociology, 40(3), 5170 DOI: 10.2753/IJS0020-7659400303

- Opaschowski, H.G. (2001). Tourismus in 21. Jahrhundert. Das gekauhte Paradies 1. Hamburg: Auflage. B.A.T. Freitzeit-Forschunginstitut GmbH, 468 pp.

- Oppermann, M. (2000). Tourism destination loyalty. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 78-84. doi:10.1177/004728750003900110.

- Pan, S., & Ryan, C. (2007). Mountain areas and visitor usage -motivations and determinants of satisfaction: The case of Pirongia Forest Park, New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(3), 288-308 DOI: 10.2167/jost662.0

- Park, D.-B., & Yoon, Y.-S. (2009). Segmentation by motivation in rural tourism: A Korean case study. Tourism Management, 30, 99-108 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.03.011

- Pollari, T. (1998). Rantasalmi-Linnansaaren kansallistpuisto. . In T. Muho-nen & S. Sulonen (Eds.), Kansallispuistojen juhlavuoden seminaari Kolilla. [The Jubilee Year Seminar of National

- Pouta, E., & Sievänen, T. (2001). Luonnon virkistyskäytön kysyntätutkimuksen tulokset -Kuinka suomalaiset ulkoilevat. In T. Sievänen (Ed.), Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2000. Luonnon virkistyskäytön valtakunnallinen inventointi, LVVI-tutkimus, 1997-2000, Loppuraportti. . Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja, 802, 32-76.

- Pouta, E. & Sievänen, T. (2002). Eteläsuomalaiset luontomatkailijat ja luontomatkojen suuntautuminen. . Terra, 114, 149-156.

- Pouta, E., Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (2004). Profiling recreational users of national parks, national hiking areas and wil-derness areas in Finland. In T. Sievänen, J. Erkkonen, J. Jokimäki, J. Saarinen, S. Tuulentie, & E. Virtanen (Eds.), Policies, methods and tools for visitor management -Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Monitoring and Manage-ment of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas. Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 2, pp. 347-354. Available at: http://www.metla.fi/julkaisut/workingpapers/2004/mwp002-en.htm.

- Pulkkinen, S., & Valta, V. (2008). Linnansaaren kansallispuiston kävijätutkimus 2006. . Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja, Sarja B, 86. 56 pp.

- Ross, E.I.D., & Iso-Ahola, S.E. (1991). Sightseeing tourists’ motivation and satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 18, 226-237 DOI: 10.1016/0160-7383(91)90006-W

- Saarinen, J. (2003). The regional economic of tourism in Northern Finland: The socioeconomic implications of re-cent tourism development and future possibilities. Scandinavian Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 3, 91-113 DOI: 10.1080/15022250310001927

- Salo, K. (1996). Kolin matkailun ja suojelun ydinkohtia sadan vuoden ajalta. . Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja, , 718, 52-58.

- Selby, A., & Petäjistö, L. (2008). Entrepreneurial activity adjacent to small national parks in Southern Finland: Are business opportunities being realised? Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 96, 39 pp. Available at: http://www.metla.fi/julkaisut/workingpapers/2008/mwp096.htm.

- Selby, A., Sievänen, T., Neuvonen, M., Petäjistö, L., Pouta, E., & Puustinen, J. (2007).

- Kansallispuistoverkoston matkailullinen luokittelu. . Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 61, 41 pp, Available at: http://www.metla.fi/julkaisut/workingpapers/2007/mwp061.htm.

- Selby, A., Sievänen, T., Petäjistö, L., & Neuvonen, M. (2010). Kansallispuistojen merkitys maaseutumatkailulle. . Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 161, 49 pp. Available at: http://www.metla.fi/julkaisut/workingpapers/2010/mwp161.htm.

- Sievänen, T., Pouta, E., & Neuvonen, M. (2007). Recreational home users -potential clients for countryside tourism? Scan-dinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 223-242. doi:10.1080/15022250701300207.

- Simpson, M., Pichler, V., Martin, S., & Brouwer, R. (2009). Integrating forest recreation and nature tourism into rural econo-my. In S. Bell, M. Simpson, L. Tyrväinen, T. Sievänen, & U. Pröbstl (Eds.), European forest recreation and tourism. London and New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 64-85.

- Sparks, B. (2007). Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1180-1192 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.11.003

- T. Sievänen et al. Downloaded by at 05:17 07 April 2015

- Sönmez, S.F., & Graefe, A.R. (1998). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 171-177. doi:10.1177/004728759803700209.

- Tapachai, N., & Waryszak, R. (2000). An examination of the role of beneficial image in tourist destination selection. Journal of Travel Research, 39(3), 37-44 DOI: 10.1177/004728750003900105

- Tian-Cole, S., & Cromption, J.L. (2003). A conceptualization of the relationships between service quality and visitor satisfac-tion, and their links to destination selection. Leisure Studies, 22(1), 65-80 DOI: 10.1080/02614360306572

- Tunturi, K. (2008). Seitsemisen kansallispuiston kävijätutkimus 2006-2007. . Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja. In Sarja. B., 95, 69 pp.

- Um, S., Chon, K., & Ro, Y.H. (2006). Antecedents of revisit intention. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(4), 1141-1158 DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.003

- Vassiliadis, C.A. (2008). Destination product characteristics as useful predictors for repeat visiting and recommendation segmentation variables in tourism: A CHAID exhaustive analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10, 439-452 DOI: 10.1002/jtr.678

- Wall-Reinius, S., & Fredman, P. (2007). Protected areas as attractions. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 839-854 DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.03.011

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26, 45-56 DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.01