Navigating spiritual competencies in caregivers: role of spiritual dryness and coping

Бесплатный доступ

During terminal illness stages, care givers are prone to spiritual dryness and may undermine their care giving reactions. Presently, spiritual caregiving is under represented in the recovery of terminally ill patients. The purpose of the study is to bring attention for spiritual integrated therapies that can be imparted in hospitals by the care givers, formally and informally. A correlational cross-sectional study was conducted in a private hospital of Pakistan. A purposive sample of 100 care givers were recruited and their responses were coded through reliable and valid instruments. Impermanence and Acceptance Scale, Spiritual Dryness Scale, Spiritual Supporter Scale and Care Giving Reaction Scale were filled through traditional paper and pen questionnaires. Parametric testing was applied. Pearson product moment correlation showed significant association among variables. Multiple linear regression showed that impermanence and acceptance and spiritual supporter scale have significant positive effects on care giving reactions. Multivariate analysis of variance shows that income has a significant main impact on the constructs. Hayes process macro analysis shows that spiritual dryness has a significant effect on care giving reactions and spiritual supporter. Independent sample t test shows that there are significant mean differences among men and women as women showed higher mean scores for the constructs.

Spiritual dryness, support, care giving, acceptance, impermanence

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211528

IDR: 170211528 | УДК: 159.9

Текст научной статьи Navigating spiritual competencies in caregivers: role of spiritual dryness and coping

People must provide spiritual care regardless of their personal spiritual beliefs. Recognizing the professional, personal, and confessional roles of caregivers is crucial in delivering effective support. Caregivers who actively engage in spiritual practices are better equipped to care for those who are suffering. Integrative approaches not only promote relaxation but also effectively alleviate psychic and spiritual distress [1].

It is imperative to consider spirituality when caring for critically ill patients. The issue of spiritual dryness among caregivers is significantly under-researched, presenting an urgent need for tailored spiritual therapies that will enhance caregivers’ effectiveness [2]. Furthermore, documenting the delivery of spiritual care is essential for accurately assessing the overall well-being of patients. Spirituality is more than just a theoretical concept; it is an increasingly recognized empirical construct that holds significant meaning when facing life-threatening illnesses, purpose, and suffering [3].

When caregivers and patients face critical news, this inevitably prompts a thorough re-evaluation of life circumstances and substantial shifts in personal beliefs. Therefore, assessing spiritual metrics during such pivotal moments is vital [4]. We require spiritually integrated interventions for caregivers to ensure comprehensive multi-professional psychosocial care. Caregivers must find meaning in the care they provide to terminally ill patients, as this reflection is essential for comprehensively analyzing their own lives and managing their suffering [5].

Theoretical Model

The family psychological well-being model emphasizes the expectations placed on caregivers regarding the care of elders within their cultural context. It explores how caregivers’ spirituality affects their overall psychological well-being [6]. In today’s world, with an increasingly burdened healthcare system, family members often need to step in for long-term care, as professional services may not fully address the need for spiritual caregiving [7].

According to the Re-signifying the Illness Process Model, spirituality plays a crucial role in life by supporting the identification of coping methods and advocating for patient rights. This model further stresses the importance of respecting individual beliefs, en- hancing the caregiving process, and providing comfort through spiritual support [8].

The Impermanence Awareness and Acceptance

It is important for caregivers to understand the challenges that arise during the treatment and recovery phases of patients. A study involving caregivers of colorectal cancer patients utilized the actor-partner interdependence model to evaluate the relationship between the patient and the caregiver. Supporting both the patient and caregiver in their self-care is essential, especially once the realities of their situation are accepted [6].

The concept of impermanence highlights that everything is transient and subject to change. It consists of three fundamental teachings: first, that all things change; second, that being alive inherently involves undeniable suffering; and third, that the self is not separate from others. This understanding promotes feelings of acceptance and awareness, creating a mindset that is open to the idea of transience [9].

Cultivating a sense of impermanence can lead to mental stability, as it allows individuals to anticipate unknown outcomes and respond with less shock [10]. This understanding helps ease acceptance of life changes and reduces disorientation during challenging times. Impermanence and acceptance are closely related to traits associated with mindfulness [11;12]. Additionally, studies suggest that women tend to demonstrate a greater awareness of acceptance compared to men [13].

The Spiritual Dryness

Spiritual dryness refers to a transient phase experienced during a spiritual crisis. This phase can be intensified by factors such as work-related stress, individual personality traits, and a lack of spiritual engagement. Individuals experiencing spiritual dryness may feel that God is unfair or distant, leading to feelings of spiritual loneliness. It can also manifest as spiritual exhaustion. Following this phase, many people find themselves moving towards spiritual serenity and acceptance [14].

Spiritual care is a crucial component of patient-centered care. In the field of gerontology, it has been observed that religiosity and spirituality play significant roles in promoting well-being as individuals age [15]. Spiritual dryness is connected to personal spiritual needs; however, the challenge lies in how these needs are communicated to the patient [16].

Caregivers often face psycho-spiritual struggles, especially when they demand better healthcare, as disparities in healthcare persist. Critical care patients may experience phases of spiritual dryness when spiritual care is lacking, which can adversely affect their mental health and overall quality of life [17]. Additionally, maintaining a positive spiritual climate is essential for caregivers to sustain their faith and hope in the recovery and treatment process [18].

The Spiritual Supporter

A Spiritual Supporter is defined based on core dimensions of spirituality that consider an individual’s relationship with God, as well as their existential quest for life’s meaningfulness, dignity, hope, forgiveness, and love [19]. Additionally, this concept relates to a person’s values, which are influenced by their culture, ethics, and morality. Caregivers should be aware of these aspects to effectively assist patients in coping during times of suffering [20].

In a study involving caregivers in palliative care, spirituality was recognized as an important component for caregivers. A significant challenge for them is living with uncertainty regarding outcomes [21]. Patients often have spiritual needs that they expect their caregivers to address. Despite facing profound psychological effects, caregivers can enhance the caring process by connecting with God and finding meaning in their work [22].

It is essential to have a clearer understanding of spiritual care, as definitions remain vague. The process of providing spiritual support and care starts with identifying spiritual needs and available resources. Furthermore, it should take into account each patient’s specific needs, which should be followed by a tailored spiritual care treatment plan [23].

The Caregiver Reaction

Caregiver reactions reflect the experiences of caregiving, including familial stress levels and the demands of the role, while also acknowledging positive aspects. Caregiving is a process that can help resolve both inter- and intrapersonal conflicts [24]. However, the experiences of informal caregivers are often overlooked, even though they frequently face significant burdens. Effective coping strategies are essential for finding a sense of normalcy and hope during challenging times [25]. Caring for a loved one through difficult healing processes is tough, and effective coping can help mitigate these challenges. Additionally, providing support for informal caregivers who care for their loved ones at home presents another significant challenge [26].

In a sample of caregivers caring for individuals with psychosis, various types of psychological distress were reported. Female caregivers generally experience better psychological well-being compared to their male counterparts. Caregivers’ perceptions of God can vary widely, ranging from loving to retaliatory, and this can influence their interpretation of suffering [27]. In another study involving caregivers of elders with dementia, the importance of having rest periods and opportunities for introspection was highlighted as crucial for managing caregiving burdens. Spiritual care may become less frequent or even cease entirely as a patient approaches the end of life [28].

Method and sample

The study is a cross-sectional correlation study complete through STROBE checklist. A purposive sample of 100 caregivers were recruited from a private hospital in Pakistan. The consent was taken to administer surveys from the hospital’s management. Pen and paper questionnaire were distributed to the care givers managing terminal illness for their patients. Only those caregivers were selected who were proficient in English Language and have been caring for a terminally ill patient since admission. The exclusion criteria contained if any of the caregiver is suffering from a mental health condition or is not immediately related to the patient. The participants were caring for a spouse, sibling, parent, or child for at least 2 months. Most caregivers were female (80 %) with a mean age of 40.3 (SD=11.0). Most of the caregivers resided with a spouse (91 %). The caregiver differed in employment as 35 % were unemployed, 10 % were only fully employed, 28 % managed their own private business and 27 % relied on savings. Hence, the important demographic factors were age, gender and employment status. Caregivers were involved in assisting patients through terminal illness, which is irreversible. Valid and reliable instruments were used. IBM SPSS v.25 was used for descriptive and inferential statistics. Parametric testing was used to explore association; multiple regression analysis was used to explore the effects. Multivariate analysis of variance was used to investigate the main impact of income on all the constructs. Independent sample test reflected on gender differences for the constructs. The Hayes process macro was used to test mediation. The instruments of use are as follows:

The Impermanence Awareness and Acceptance Scale is a 13-item self-report measure with two dimensions, impermanence awareness and impermanence acceptance, which both indicate towards transiency

[10]. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale is greater than 0.70. Some of the items include, «I am aware of the impermanence of all things», «I know that aspects of myself will change with time», «When my role in a group changes, I feel anxious». The scale is scored on 7 7-point scale.

The Spiritual Dryness Scale is a multifaceted questionnaire with a version for spiritual and religious persons that consists of 10 items [14]. The Acedia symptoms subscale has 14 items. Coping strategies with phases of spiritual dryness have 14 items. Overall, Cronbach’s alpha is .87. Some of the items are, «I have a feeling that I am spiritually empty», «I have found ways to deal with these feelings», «I have trust and faithfulness in God», «intensify my community life». The scale is scored on 5 5-point scale.

The Spiritual Supporter Scale assesses competency to provide spiritual care [19]. The scale has 31 items. Overall, Cronbach’s alpha is 88. Some of the items include, «spirituality is related to the sphere of inner human life», «the presence of loved ones gives my life meaning», «I know how to be truly present with a suffering person». The scale is scored on 4 4-point scale.

The Caregiver Reaction Scale has 9 subscales and a total of 55 items [24]. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is greater than. 82. Some of the items include «wish you could just run away» , «feel stressed by your relative’s illness and needs», «feel trapped by your rel- ative’s illness», and «in general, feel competent as a caregiver». The scale is scored on 4-point scale. The subscales are role captivity, overload, relational deprivation, competence, personal gain, coping, family beliefs and conflict, job conflicts and financial disruption.

It is hypothesized that impermanence and acceptance, spiritual support and spiritual dryness have significant associations. Impermanence and acceptance and spiritual support have a positive effect on caregiver reactions. Spiritual dryness is a significant mediator between caregiver reactions and spiritual support. Men and women show significant mean differences on all four constructs. Income has a significant main impact on all four constructs.

Results

Table 1 shows that impermanence and acceptance, spiritual dryness and subscales spiritual supporter, and care giver reaction scales and sub scales show moderate to strong associations.

Table 2 shows robust psychometric properties for the scales and subscales. After testing for normality through skewness and kurtosis values, the data was fit for parametric testing.

Table 3 shows that impermanence ( B=0.104,p<.01), acceptance (B=0.061,p<.01) and spiritual supporter (B=0.561,p<.01) have significant positive effects on care giving reactions.

Table 1

|

Correlation Analysis |

||||||||||||||||

|

Scales 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

1.IAW - |

0.66** |

0.70** |

0.55** |

0.58** |

-0.48* |

0.67** |

-0.49* |

-0.50** |

-0.46* |

0.58** |

0.61** |

0.66** |

0.71** |

-0.54** |

-0.49* |

0.70** |

|

2.IAC - |

- |

0.67** |

.54** |

0.49** |

-0.50** |

0.70** |

-0.65** |

-0.49* |

-0.50** |

0.54** |

0.60** |

0.61** |

0.70** |

-0.53** |

-0.42* |

0.68** |

|

3.IAAT - |

- |

- |

0.44* |

0.47** |

-0.49* |

0.68** |

-0.62** |

-0.45** |

-0.48** |

0.51** |

0.49** |

0.58** |

0.67** |

-0.51** |

-0.45* |

0.66** |

|

4.SDS |

- |

0.59** |

-0.60** |

-0.62** |

-0.59** |

-0.54** |

-0.45** |

0.53** |

0.44* |

0.51** |

0.64** |

-0.49** |

-0.44* |

0.69** |

||

|

5.CO |

- |

-0.55** |

0.58** |

-0.59** |

-0.53** |

-0.58** |

0.60** |

0.47** |

0.59** |

0.63** |

-0.50** |

-0.49* |

0.70** |

|||

|

6.SDST |

- |

-0.54** |

0.48* |

0.55** |

0.55** |

0.51** |

0.52** |

-0.54** |

0.54** |

0.55** |

0.69** |

0.70** |

||||

|

7.SST |

- |

-0.48** |

-0.50** |

-0.49* |

0.55** |

-0.41* |

0.59** |

-0.49* |

-0.45* |

0.69** |

0.81** |

|||||

|

8.RC |

- |

0.69** |

0.59** |

-0.48* |

0.39* |

0.50** |

0.49** |

0.69** |

0.71** |

-0.62** |

||||||

|

9.OV |

- |

0.67** |

-0.59** |

-0.58** |

-0.61** |

0.69** |

0.71** |

0.68** |

-0.58** |

|||||||

|

10.RD |

- |

-0.44* |

0.58** |

0.53** |

0.49** |

0.65** |

0.68** |

-0.60** |

||||||||

|

11.CP |

- |

-0.33* |

0.44* |

-0.39* |

-0.45* |

-0.40* |

0.68 |

|||||||||

|

12.PG |

- |

-0.41* |

-0.40* |

-0.54** |

0.46* |

-0.60** |

||||||||||

|

13.COP |

- |

-0.59** |

0.52** |

-0.30* |

0.69** |

|||||||||||

|

14.FB |

- |

0.60** |

0.56** |

-0.55** |

||||||||||||

|

15.JC |

- |

0.63** |

-0.61** |

|||||||||||||

|

16.FD |

- |

-0.55** |

||||||||||||||

|

17.CGT |

- |

|||||||||||||||

Note: IAW=impermanence, IAC= acceptance, IAAT=impermanence and acceptance, SDS=spiritual dryness, CO=coping, SDST= aggregate spiritual dryness, SST=spiritual supporter, RC=role captivity, OV= overload, RD= relational deprivation, CP= competence, PG= personal gain, COP=coping, FB=family beliefs and conflict, JC=job conflicts and FD=financial disruption, CGT=aggregate care giving. p<.01**, p<.05*.

Table 2

|

Psychometric Analysis |

|||||

|

Scales |

k |

M(SD) |

α |

Skewness Kurtosis |

|

|

IAW |

7 |

4.11(1.22) |

.56 |

0.74 |

-.118 |

|

IAC |

6 |

4.11(1.30) |

.72 |

1.01 |

3.62 |

|

IAAT |

13 |

5.22(2.01) |

.86 |

1.32 |

1.97 |

|

SDS |

14 |

4.31(2.22) |

.84 |

1.52 |

2.27 |

|

CO |

14 |

9.23(2.01) |

.79 |

2.22 |

2.36 |

|

SDST |

28 |

8.21(1.70) |

.89 |

1.45 |

0.85 |

|

SST |

31 |

8.20(3.31) |

.77 |

1.10 |

-0.49 |

|

RC |

5 |

3.90(1.20) |

.54 |

1.16 |

0.34 |

|

OV |

7 |

3.21(1.54) |

.58 |

0.54 |

0.12 |

|

RD |

4 |

3.91(1.60) |

.59 |

0.44 |

0.45 |

|

CP |

4 |

3.11(1.20) |

.59 |

0.11 |

-1.21 |

|

PG |

11 |

5.45(1.30) |

.60 |

0.21 |

-3.40 |

|

COP |

4 |

5.21(1.40) |

.62 |

-0.33 |

-1.20 |

|

FB |

5 |

9.20(1.22) |

.64 |

0.55 |

-1.56 |

|

JC |

4 |

6.50(1.45) |

.66 |

.577 |

-.049 |

|

FD |

3 |

4.30(1.22) |

.81 |

0.65 |

.755 |

|

CGT |

55 |

5.20(1.90) |

.89 |

0.66 |

-.220 |

Note: IAW=impermanence, IAC= acceptance, IAAT=impermanence and acceptance, SDS=spiritual dryness, CO=coping, SDST= aggregate spiritual dryness, SST=spiritual supporter, RC=role captivity, OV= overload, RD= relational deprivation, CP= competence, PG= personal gain, COP=coping, FB=family beliefs and conflict, JC=job conflicts and FD=financial disruption, CGT=aggregate care giving

Table 3

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

Table 4 shows the females are significantly different in mean scores from males. Females show more acceptance to impermanence, prone to higher spiritual dryness, cope better and are better spiritual supporters. Women feel burdened more by role captivity, overload, relational deprivation. In caregiving, women

Table 4

Independent sample t -test

|

Variables |

Females (n=50) |

Males (N=50) |

||||||

|

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

t |

df |

p |

Cohen’s d |

|

|

IAW |

12.33 |

8.33 |

6.21 |

1.21 |

12.32 |

98 |

.000 |

1.03 |

|

IAC |

8.57 |

1.24 |

3.21 |

1.32 |

16.23 |

98 |

.000 |

4.19 |

|

IAAT |

15.43 |

1.23 |

12.32 |

2.21 |

26.12 |

98 |

.000 |

1.74 |

|

SDS |

23.18 |

1.11 |

14.32 |

1.43 |

9.12 |

98 |

.000 |

8.70 |

|

CO |

38.17 |

1.23 |

13.42 |

3.23 |

32.12 |

98 |

.000 |

10.12 |

|

SDST |

32.12 |

0.83 |

15.30 |

1.09 |

-23.12 |

98 |

.000 |

17.36 |

|

SST |

38.60 |

1.22 |

12.43 |

3.32 |

-3.34 |

98 |

.000 |

1.53 |

|

RC |

21.80 |

1.33 |

10.01 |

2.30 |

17.65 |

98 |

.000 |

4.83 |

|

OV |

17.32 |

1.23 |

10.21 |

3.12 |

-4.32 |

98 |

.000 |

1.22 |

|

RD |

11.65 |

3.43 |

10.12 |

2.40 |

-0.61 |

98 |

.001 |

0.18 |

|

CP |

25.65 |

4.12 |

16.54 |

5.65 |

-0.99 |

98 |

.000 |

1.84 |

|

PG |

30.20 |

1.09 |

14.32 |

2.32 |

13.32 |

98 |

.000 |

8.76 |

|

COP |

30.12 |

1.34 |

11.23 |

2.10 |

12.32 |

98 |

.000 |

10.73 |

|

FB |

22.45 |

1.90 |

9.01 |

3.21 |

21.21 |

98 |

.000 |

5.09 |

|

JC |

48.94 |

2.33 |

10.19 |

3.12 |

13.23 |

98 |

.000 |

14.07 |

|

FD |

30.73 |

3.01 |

13.56 |

4.13 |

21.32 |

98 |

.000 |

4.75 |

|

CGT |

86.73 |

1.09 |

50.43 |

1.43 |

23.34 |

98 |

.000 |

28.55 |

Note: IAW=impermanence, IAC= acceptance, IAAT=impermanence and acceptance, SDS=spiritual dryness, CO=coping, SDST= aggregate spiritual dryness, SST=spiritual supporter, RC=role captivity, OV= overload, RD= relational deprivation, CP= competence, PG= personal gain, COP=coping, FB=family beliefs and conflict, JC=job conflicts and FD=financial disruption, CGT=aggregate care giving

are more affected for relational deprivation, are more competent and work towards personal gain. Females are highly involved in family conflict and may face greater job conflicts and financial disruption while care giving.

Table 5

Multivariate Analysis of Variance

|

Dependent variable |

Quarterly Income(Rubles) |

MD (S.E) |

p |

|

IAAT |

13,809 -27,619 |

-4.60(2.14) |

.201 |

|

27,895-41,428 |

5.23(1.98) |

.021 |

|

|

41,704-55,238 |

.607(2.66) |

.000 |

|

|

SDST |

13,809 -27,619 |

5.90(1.88) |

.110 |

|

27,895-41,428 |

4.99(1.87) |

.033 |

|

|

41,704-55,238 |

7.60(.677) |

.004 |

|

|

SST |

13,809 -27,619 |

.971(.551) |

.004 |

|

27,895-41,428 |

-1.173(.449) |

.003 |

|

|

41,704-55,238 |

1.36(.332) |

.001 |

|

|

CGT |

13,809 -27,619 |

2.21(.212) |

.000 |

|

27,895-41,428 |

3.21(.242) |

.002 |

|

|

41,704-55,238 |

2.32(.245) |

.000 |

Note: IAAT= impermanence and acceptance, IAAT=impermanence and acceptance, SDST= spiritual dryness SST=spiritual supporter, CGT= care giving

Table 5 shows that impermanence and acceptance for middle-income (13809–27,619 Russian Rubles, 50,000–100,000 Pakistani Rupees) and high income earners (41,704–55,238 Russian Rubles, 101,000– 150,000 Pakistani Rupees) is significant. Spiritual dryness is only significant for middle and high-income earners. Spiritual supporter scores is significant across all income groups, as well as for caregiving. Hence, overall there is a main impact of income on impermanence and acceptance, spiritual dryness, spiritual support and caregiving reactions.

Table 6

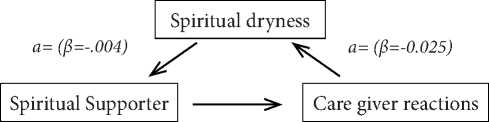

Mediation Analysis

|

Effect |

β(coefficient) |

S.E |

p |

LL |

UL |

|

Indirect |

-0.04 |

2.03 |

-0.21 |

0.054 |

|

|

effect (a*b) Direct -0.025 |

.114 |

.001 |

-0.443 |

-0.023 |

|

|

effect (c ‘) Total effect -0.065 (c) |

.068 |

.002 |

-0.321 |

0.032 |

|

Note: IAW=impermanence, IAC= acceptance, IAAT=impermanence and acceptance, SST=spiritual supporter

According to Table 6, there is significant mediating effect of spiritual dryness between spiritual supporter and care giver reactions.

Mediating effect of spiritual dryness between spiritual supporter and care giver reactions

а=(в=-0.065)

Discussion

Research indicates that spiritual dryness negatively impacts caregiving activities, primarily due to emotional exhaustion and burnout associated with these responsibilities, especially when there is low hope for recovery [29]. Spiritual care interventions are crucial as they reflect human conditions and aspects of self-transcendence, addressing intrinsic issues and potentially reducing fatigue associated with beliefs. It is essential to implement spiritual care interventions for caregivers, focusing on exploration of spirituality, healing presence, therapeutic self, intuition, patient-centered care, meaningfulness, nurturing environments, and empirical documentation of spiritual care delivery [30]. Unfortunately, spiritual care is often the most neglected aspect of mental and physical well-being in palliative care [31]. Integrating spirituality into interventions for caregivers can lead to improved mental health outcomes for both patients and caregivers. In addition, emphasizing spirituality can enhance caregivers’ attitudes toward terminally ill patients [32].

Currently, there is a shortage of spirituality-trained practitioners who are formally recognized as professionals. Consequently, therapists and trainers should participate in similar training programs to enhance their skills and provide effective training in hospitals, hospices, clinics, and home care settings. Recognition through spiritual care assessments can facilitate this process [33].

The transition roles of caregivers in end-of-life care can be challenging. Studies reflect the burden caregivers experience, which can lead to turmoil and conflict, negatively affecting their health [34]. Therefore, support is vital to manage the adverse effects associated with caregiver stress. According to Bridges’ (1991) transition theory, this phase can be particularly diffi- cult, especially when patients are facing imminent death [35]. As a result, caregivers may experience a significant decline in their physical and mental health. In some cases, caregiving may cease entirely when death is certain. This underscores the importance of spiritual support, which can foster acceptance and renewal of spirituality through innovative interventions [36].

Furthermore, factors such as overload, financial strain, and role captivity are common causes of spiritual burnout among caregivers engaged in longterm care [37]. Family caregiving often leads to time constraints and can create role conflicts that are challenging to navigate [38],[39]. However, spiritual in- clinations and trust in God can assist individuals from various faith backgrounds, making the caregiving process more manageable [40], promoting spiritual support, and alleviating spiritual dryness in long-term care delivery [41].

Conclusion

Care givers must also receive spiritually integrated training and therapy to cope better with the ailing patients. The caregivers can expect hope and a healthy recovery in the process. Amidst care, the caregivers may also face many challenges that can be solved through spiritually integrated therapies that must be imparted formally and informally.