New engravings from Abri du Poisson (Dordogne, France)

Автор: Zotkina L.V., Cleyet-merle J.J.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Art. The stone age and the metal ages

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145325

IDR: 145145325 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.3.041-047

Текст статьи New engravings from Abri du Poisson (Dordogne, France)

The Abri du Poisson rock-art site is located on the right side of a small ravine known as Gorge d’Enfer, between the locality of Laugerie Basse and a bridge across the Vézère River, close to the railway station of the town of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil (Dordogne) (Breuil, 1952: 304–305; Delluc B., Delluc G., 2009: 51). It was discovered in 1892 by P. Girod. Since that time, repeated excavations have been conducted here: in 1898, by Galou*, in 1912, by J. Marsan, and in 1917–1918, by D. Peyrony (Roussot, 1984: 154).

On December 11, 1912, Marsan discovered a large bas-relief representation of a fish on the rock-shelter roof (Peyrony, 1932: 246; Delluc B., Delluc G., 1997: 171). In 1917, with the help of brushes and a large amount of water (Peyrony, 1932: 263), the roof was cleared of the moss, abundantly growing in the humid environment of Dordogne forests and often covering open areas of limestone, which forms the main elements of the terrain’s relief in this region. According to Peyrony, no other images were found, apart from the fish and an adjacent unidentified relief representation that, obviously, preceded it (Ibid.). Since the limestone is rather soft, it can be assumed that some drawings from Abri du Poisson were not only damaged, but completely erased. Possibly, this fact influenced the selected line of research: only distinctive figurative elements were

studied. Much less attention was paid to small fragments and feebly-marked lines. Specialists point out that the roof was, probably, insufficiently examined: “A large number of engraved elements, which may represent lines of backs, legs, horns, tails, or eyes of animals, can be observed everywhere on the rock-shelter ceiling… Careful tracing over the outlines could reveal new images” (Roussot, 1984: 155).

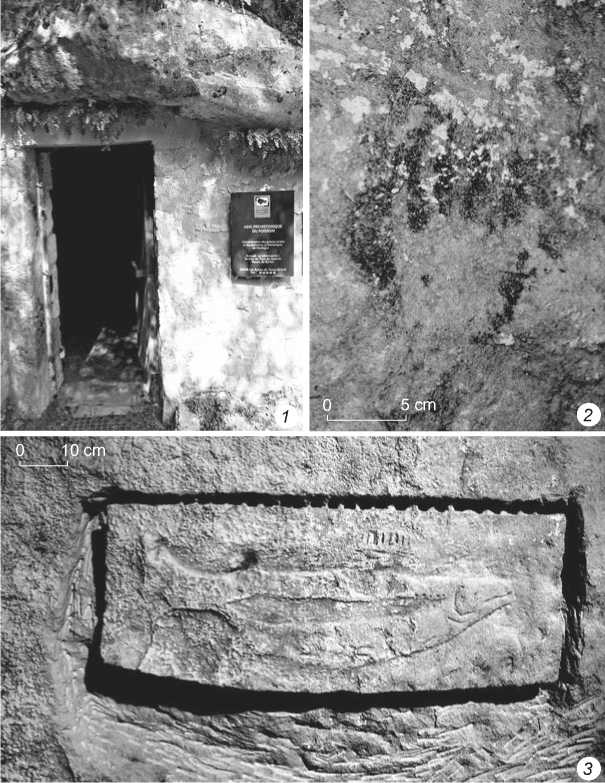

As already mentioned above, Abri du Poisson is famous for a very bright realistic representation of a salmon (Fig. 1, 3 ). This is a bas-relief located in the left part of the rock-shelter and being about 105 cm in length and 28 cm in the widest place, i.e. life-size, with a large number of anatomical details (Peyrony, 1932: 263; Roussot, 1984: 155). Roussot was also the first to record the barely perceptible traces of red pigment in the protruding areas of the bas-relief (Roussot, 1984: 155). The pigment is also present in the cultural deposits of Abri du Poisson (Cleyet-Merle, 2016: 10).

In December 1975, in the right part of the rock-shelter, S. Archambault and A. Roussot found a small (about 10 cm) negative of a hand, made in a black pigment, namely manganese oxide (Roussot, 1984: 154) (Fig. 1, 2). In 1983, B. Delluc and G. Delluc identified the engraved lines on a large limestone block (about 2 m high), earlier mentioned by Peyrony, as an image of the female sign (Delluc B., Delluc G., 1991).

In addition to the above depictive elements and bas-relief on the rock-shelter’s roof, several rock blocks with whole images (or fragments of them) were also found in the cultural layer (Peyrony, 1932: 259–263; 1952: 566). Some of these blocks, which are currently stored in the museum, show traces of red pigment similar to those on the rock-shelter’s roof (Ibid.).

Chronological attribution of the images

Peyrony has identified five lithological layers, in two of which cultural remains were recorded: in the first case, they belonged to the Early Aurignacian (layer b), and in the second case, to the local Gravettian variant, of which the Noailles burins are typical (layer d) (Roussot, 1984: 154; Jaubert, 2008: 226; Cleyet-Merle, 2016: 10).

It has been established that these cultural

layers are separated by a sterile yellowish interlayer (layer c), presumably related to desquamation due to cryoclastism (Ibid.).

In the Aurignacian layer, several rock blocks were found with figurative elements in relief, such as the female sign, fragmentary images of ungulates, etc. Peyrony (1932: 259) did not find them in situ , but when studying the dump left by the previous excavations conducted by Girod. However, the lithic industry and the general archaeological context have made it possible to assign the limestone blocks with figurative elements to the Aurignacian (Ibid: 259– 262). A schematic representation of the lower part of a female body is very typical for this period (Geneste, 2017). The closest analogs are discovered in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave (about 35 ka BP) and at the open locality of La Ferrassie (Cleyet-Merle, 2016: 29). Thus, the majority of researchers have no doubt about attribution of these images to the Aurignacian. The only question is

Fig. 1. Abri Du Poisson and the best-known images of this site. Photograph by L.V. Zotkina.

1 – general view of the site; 2 – negative of a hand, made in black pigment; 3 – bas-relief of a fish.

whether these blocks were specially brought to the site, or whether they split off from the roof (Ibid.).

It is commonly believed that since the Aurignacian layer is covered by a rather thick interlayer, which was presumably formed as a result of intense desquamative destruction of surface of the rock-shelter roof, the surviving images were made after completion of these natural processes. Thus, the appearance of the drawings and bas-relief can be referred to the later layer dated to the Gravettian (27 ka BP) (Ibid.: 28). However, at present, this argument is considered unreliable, since the geomorphology of the rock-shelter has not so far been studied comprehensively. It is reasonable to suppose that the roof was less affected by destructive processes than previously thought, and that external factors could have played a big role in filling the space between the floor and the ceiling of the rock-shelter (Ibid.: 10). Therefore, today we cannot state with full confidence that the destruction affected exactly the roof of the Abri du Poisson, where the images are represented, rather than other areas, from which limestone blocks could have been split off to create a sterile interlayer. So, the fact that the images are preserved on the roof does not prove that they pertain to the later periods than the Aurignacian.

Roussot draws attention to the technique used by an ancient artist to express the fish image. The bas-relief technique allows the representation of a salmon from Abri du Poisson to be correlated with the famous “Venus” of Laussel, which is reliably dated to the Gravettian (Roussot, 1984: 155). However, this cannot be a reason for referring the fish representation exclusively to this period, since such technique was typical not only of the Gravettian. Various types of relief were often used later: for example, in the Solutrean. One of the most striking examples is a rock block with representations of bulls from Fourneau du Diable, found in a layer attributed to that time (18.6–19.0 ka BP) (Cleyet-Merle, 2016: 57). Though certain tendencies in the development of image creation techniques can be traced in the cave art, none of them can be considered an unambiguous chronological marker.

Since the handprint in Abri du Poisson is made with manganese oxide, direct dating of the pigment is impossible. Nevertheless, many positive and negative prints known in the caves of the Franco-Cantabrian region are assigned to the Gravettian (some images in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc and Cosquer caves are made with charcoal, which has allowed their radiocarbon dating within 27–22 ka BP) (Foucher, San Juan-Foucher, Rumeau, 2007: 83). There are many directly dated images of this category, and most of them belong to the Gravettian period; however, the possibility of different chronological attribution of certain samples cannot be completely ruled out. Thus, at present, the scientific community is of the opinion that the handprint from Abri du Poisson pertains to the Gravettian (Cleyet-Merle, 2016: 29).

Apart from the most distinct images, which are clearly identified on the roof’s surface, evident figurative elements, covered by a later bas-relief, are observed. First of all, this refers to an unclear image, on top of which the fish representation is made. This element was interpreted by researchers in different ways: Peyrony treated it as the head of a carnivorous bird (Peyrony, 1932: 267), Leroi-Gourhan as a fragment of the back of a bison, and Abbot Breuil, as the head of an eagle or rhinoceros (Roussot, 1984: 155). It is rather difficult to determine the subject of this representation, but it can be stated with confidence that this surface area was intentionally reworked. The problem consists in determining whether this transformation was related to a change in cultural tradition, and if this “hidden” fragment pertains to a more ancient period than the fish representation.

So, at the moment, at least two large periods of image creation, the Aurignacian and the Gravettian, can be distinguished in Abri du Poisson. Both are associated with the archaeological filling of the site. There is a great likelihood that separate stages can be also distinguished within these large periods. However, while attribution of the images found in the archaeological layer relating to the Aurignacian does not cause serious doubts, the issue of their belonging to the Gravettian should be considered open, since direct dating of each individual image or figurative element on the rock-shelter roof is impossible.

The “fish” rescue history

As was mentioned above, the salmon representation attracted many researchers, but not only these. The attempts of local people to recover and sell the bas-relief abroad are widely known. These precedents, actually right after the opening of the representation in 1912, provoked Peyrony to initiate a campaign to change French legislation as regards protection of historical and cultural heritage. Thus, the Abri du Poisson locality became one of the touchstones in the development of a system of measures and principles aimed at the preservation of cave art and archeology sites in general (Fig. 1, 1 ). And as early as December 31, 1913, the first act on protection of historical sites was passed (Découvertes…, 1984: 31). But this factor, obviously, also influenced tendencies in the study of Abri du Poisson: researchers put a greater emphasis only on the fish representation. Naturally, such a subject, quite unusual for Paleolithic art, and the events around the site, aroused great interest from the public. Partly because of this, somewhat less attention was paid to other figurative elements of the site.

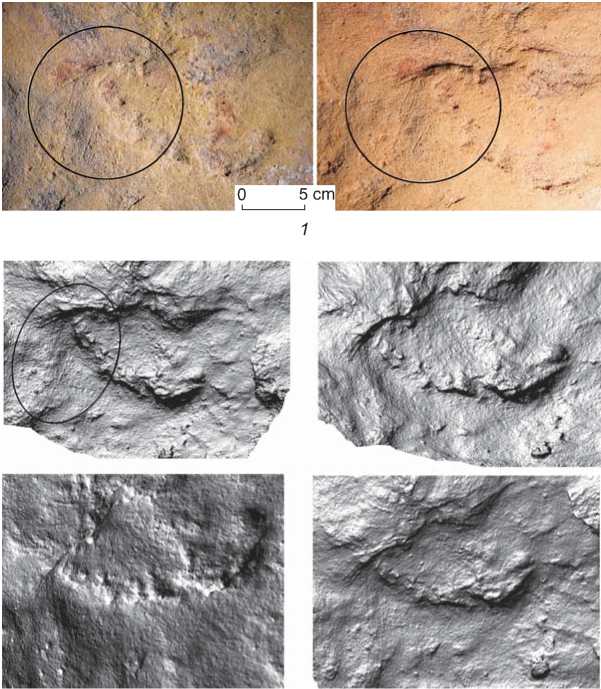

Fig. 2. Photographs of thin engraved lines illuminated by a modern LED lamp ( 1 ) and by a lantern manufactured in the 1960s ( 2 ). Photograph by H. Plisson.

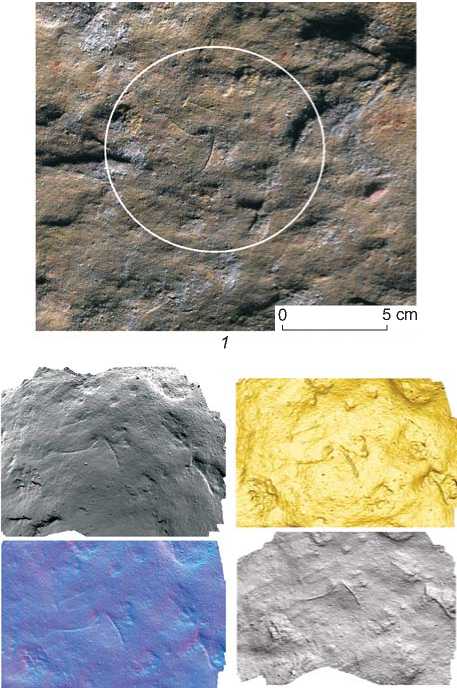

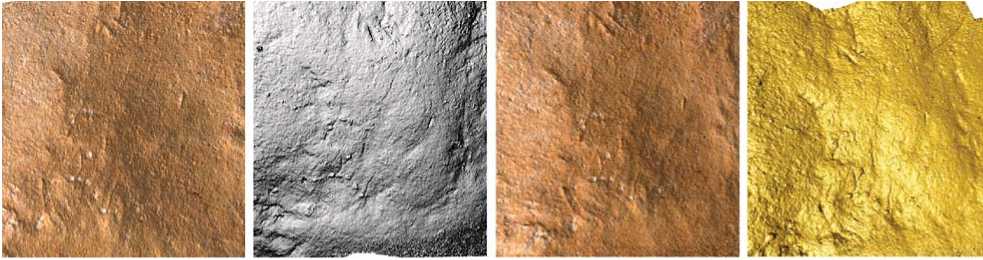

Fig. 3. A partial zoomorphic image, made in the engraving technique.

1 – photographs; 2 – 3D reconstruction of the image at various angles and with various filters.

New Engravings from Abri Du Poisson

An important factor influencing the possibilities that researchers had in the past was the quality of illumination devices available in those years. Examinations of the rock-shelter walls and roof were conducted mainly before the advent of powerful lightemitting-diode lamps. In the preparation of this article, a small experiment was set up to demonstrate the difference between the modern possibilities and the means that were available to researchers of the past. Photographs were taken using different illuminating devices: a modern LED lamp and a lantern manufactured in the 1960s, with a similar arrangement of light sources (Fig. 2). They testify that the technical capabilities of the past rarely allowed all the finest details of relief to be revealed, which means that it was extremely difficult even to see some fragments of images. As can be clearly seen in the photographs, the LED lamp provides diffuse and even light, illuminating a larger surface area uniformly (Fig. 2, 1 ), which cannot be said of the old lantern that gives too sharp lighting at the center and much fainter, insufficient illumination on the periphery (Fig. 2, 2 ).

Several new images were identified during the approbation of traceological analysis on Dordogne cave art materials in 2016*. Earlier, some of these had been described in reports as series of disordered lines (Cretin et al., 2013: 54– 60), while others were not mentioned by the researchers at all. Despite the artificial transformations experienced by the rockshelter roof during cleaning, at a certain level of illumination, relief elements of various scale and intensity (from thin lines to bas-relief fragments) can be observed. The preliminary studies have resulted in discovery of the following representations.

-

1. A partial zoomorphic image made by engraving and with the use of the natural relief of the limestone surface (Fig. 3)*: a hind leg, a tail, and a croup,

-

2. A schematic representation of a horse’s head, made with the deep engraving technique (Fig. 4). Small details are absent, possibly owing to surface cleaning; however, at proper oblique illumination, the general outline of the head and neck can be seen fairly well. Furthermore, natural recesses were probably used to represent the neck and the mane. This relief is rather clearly seen in threedimensional reconstructions (Fig. 4, 2 ). However, it is still premature to conclude as to whether these recesses relate to the image, or are arranged in such an order by chance.

-

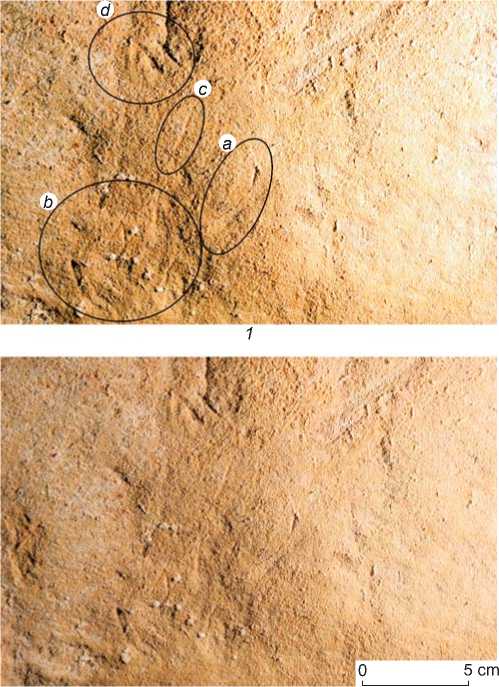

3. A detailed representation of a horse’s head, made with the fine engraving technique (Fig. 5, 6). This is one

rendered in a schematic manner. It is hard to tell exactly what kind of animal the ancient “artist” tried to depict, but the croup line passes smoothly into the back, which represents a natural convex relief (Fig. 3, 2 ). The roof’s surface in the area of this representation has a reddish tone (Fig. 3, 1 ). Possibly, these are traces of artificial coloration, though the probability of natural ferrugination cannot be excluded either.

of the most interesting images. The muzzle’s outlines are clearly discernible, and a drop-like element, obviously rendering a nostril, is well traced towards the muzzle’s end (see Fig. 5, 1 , a , b ). Above the cheek contour, a thin line, seemly dividing the image into two parts, can be observed (Fig. 5, 1 , c ). The ears are rendered by two small triangles (Fig. 5, 1 , d ). It is also important to note that the face’s contour is doubled (see Fig. 6). It cannot be ruled out as yet that two different images are presented here.

In one of the papers summarizing the cave art of France, A. Roussot points out that M. Sarradé recorded a representation of the front of a horse approximately one meter from the fish bas-relief image, close to the entrance of Abri du Poisson. Judging by the text, this message was oral; however, the author was skeptical of it (Roussot, 1984: 155). Thus, there is a probability that the image found by us in 2016 was the one earlier recorded by Sarradé.

Other lines and various elements of artificial surface preparation were also discovered, such as bored recesses

Fig. 4. A representation of a horse’s head and neck, made in the deep engraving technique.

1 – photograph; 2 – 3D reconstruction of the image at various angles and with various filters.

Fig. 5. A detailed representation of a horse’s head, made in the fine engraving technique (photographs at various illumination). a – cheek contour; b – nostril and muzzle contour; c – muzzle-dividing line; d – ears.

Fig. 6. 3D reconstruction of the horse-head image (see Fig. 5) at various angles and with various filters.

in the right part of the rock-shelter, similar to those observed on the fish image; however, these finds are not described in this article, because they require further systematic and more detailed studies taking into account the context, natural surface relief, etc.

Conclusions

In certain cases, these are traceological criteria and 3D visualizations that allow depictive elements to be revealed, including the presence of compacted smoothed surface; a pronounced artificial relief, differing from the desquamation cracks; an inclination angle of protruding parts, close to 90°; etc. Such features, taken together, can provide additional information about artificial treatment of a surface, since it is not always possible to discover distinctive figurative elements. For example, sometimes it is not easy to determine immediately whether a deep grooved line represents an image fragment. However, from the type of traces and traceological characteristics, it can be established whether we deal with a treated area, or with natural changes of the limestone surface. Probably, such approach will allow us to reveal more depictive elements or whole images in Abri du Poisson, where many disordered lines are observed that cannot be interpreted as yet.

At present, the lines of research that seem to become topical for Abri du Poisson in future may be defined as follows:

-

1) consistent examination and study of the roof and walls, in order not merely to reveal new depictive elements, but also to understand the relationship between the already-known images and those discovered during the last examination;

-

2) producing of a technical drawing that would allow the designation of the location of each figurative element and whole image in Abri du Poisson;

-

3) monitoring of the degree of preservation of the whole surface and of individual traces of artificial treatment;

-

4) traceological analysis of all images, including those on rock blocks stored in museum collections, and correlation of their technological characteristics and degree of preservation with regard to different conservation conditions (comparison of images in the rock-shelter and in the museum);

-

5) traceological analysis of stone inventory (collections obtained mainly during excavations conducted by Peyrony);

-

6) study of pigments of various shades and intensity, and of various degrees of preservation, determining the limits of their distribution on the rock-shelter roof, and establishing the genesis of traces of red pigment;

-

7) geomorphological and karstological study of the rock-shelter as a whole, and of its individual areas relating to images.

Comprehensive studies and systematic documentation of this site will facilitate not only the refinement of the available data and, possibly, the identification of new images, but will also enable the monitoring of the processes of surface degradation of the rock-shelter’s roof and walls.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 14-50-00036).The authors express their gratitude to the International Associated Laboratory (Laboratoire international associé – LIA) ARTEMIR and its Coordinator H. Plisson.