Objects of portable art from a Bronze Age cemetery at Tourist-2

Автор: Basova N.V., Postnov A.V., Molodin V.I., Zaika A.L.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145461

IDR: 145145461 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4.053-065

Текст статьи Objects of portable art from a Bronze Age cemetery at Tourist-2

Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations of small sizes, made in various techniques using various materials, were common among the ancient population of Eurasia. Such items were a part of the semantic system, and reflected the worldview of the indigenous population. Owing to their special sacred value, objects of portable art have been found very rarely in closed archaeological complexes. One of the sites, the materials of which substantially enrich the collection of movable art from the southwestern Siberia, is a cemetery of the Bronze

Age discovered in 2017 at the territory of the Tourist-2 settlement in the city of Novosibirsk. The site is located on the elevation of a floodplain terrace on the right bank of the Ob River 1.3 km north of the mouth of the Inya River (Fig. 1). This site has been studied since 1990, and was fully explored in 2017 during the rescue works on the area of over 0.6 ha (Basova et al., 2017). Since the purpose of these works was complete investigation of the Tourist-2 settlement, it was unpractical to register the cemetery with the state guard and assign it an individual name.

In total, 21 burials of the Bronze Age have been discovered. Owing to intensive use of the territory

Description of the objects of portable art

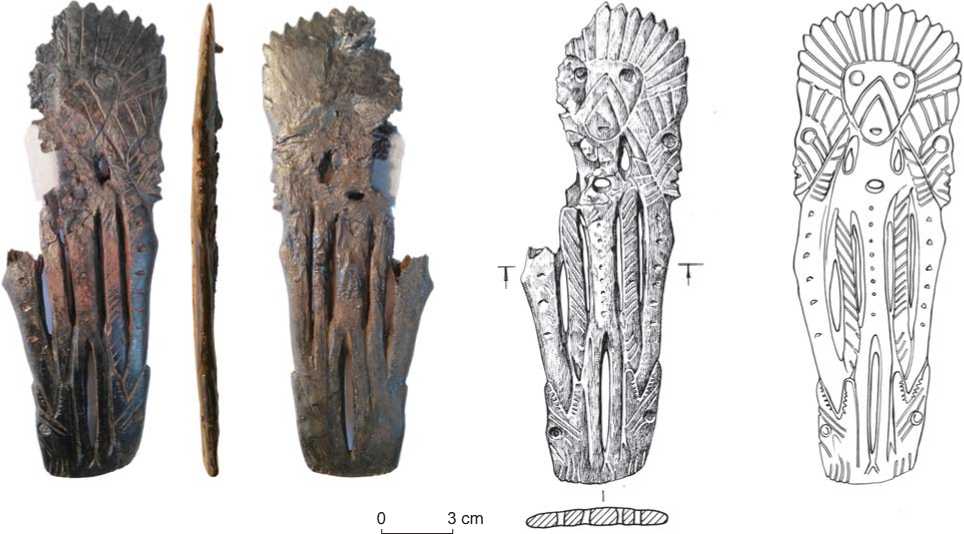

Belt buckle (burial 1). This item is flat, elongated, and of trapezoidal shape expanding upwards. Standing anthropomorphic figures (Fig. 2) are represented on the front surface. The length of the artifact is 9.3 cm; its width is 6.3, and its thickness is 0.3 cm. Its material is burl. The tripartite vertical composition of standing human images of gracile physical constitution consists of the central frontal figure and two side profile figures symmetrically turned to the central figure with their backs. The upper left part of the item was damaged: only the legs have survived from the lateral figure, but it must have been similar to the right figure; the central anthropomorphic image was also partly damaged. Two symmetrically located fish (pike?) heads, protrude and join to the extremities of the anthropomorphic figures at the base of the item.

The trunk and extremities of the central figure were marked with deep, sometimes through openings partly duplicated on the back of the item. The body is narrow and long; it ends with relatively short thin legs slightly turned at the knees and joined together at the level of the feet which were practically left unmarked. The shoulders

Fig. 1. Location of the Tourist-2 settlement.

Fig. 2 . Belt buckle with anthropomorphic representations (burl).

are narrow and weakly expressed. The arms are straight, disproportionately long; they reach the level of the knees. At the bottom, their contour slightly widens; the pointed ends of the hands touch the lower jaws of the fish. A mask of a sub-triangular shape is depicted above the long neck with engraved lines. Large round eyes were made by shallow drilling with a tool with flat working edge. They are widely spaced and were located in the upper corners of the mask. The rounded contour of the mouth is weakly expressed. Two pairs of parallel diagonal lines of a “tattoo” extend from the area of the nose, which was not shown, to both sides of the “mouth”. Straight engraved lines diverge from the upper contour of the mask in a fan-like manner; carved denticulate protrusions were formed between their ends. This gives certain reasons to interpret this element as a headdress made of feathers, or sun rays. A chain of miniature rounded impressions appears on the body along the vertical axis, and frequent oblique incisions were made on the arms.

The face depicted in profile looks more realistic, and its features were carefully modeled: protrusion of the eyebrow ridges, straight nose, open mouth, and pointed chin were rendered in relief. The lower jaw and neck were emphasized by scraping/shaving. The round eye was made by the same tool as eyes in the central figure. The slanting lines of the “tattoo” were supplemented by parallel paired lines extending from the eye. Straight lines representing the headdress extend radially from the semicircular contour of the face. Unlike the central image, these lines descend to the level of the neck, where the distance between them is significantly reduced. The body of the figure is narrow and extremely stylized; small angular ledge is present at the level of the chest. The body gradually narrows downward passing into the lower extremities inscribed into the open jaws of the fish.

Images of fish (pike?) heads, symmetrically located in the lower part of the item on both sides of the legs of the central figure and turned vertically upward, were made using engraving technique in the same stylistic manner. They are shown with open mouths; jaws are long, narrow, and pointed; teeth were rendered by small incisions. The eyes are round; paired slanting lines of the “tattoo” were carved between the eyes and mouth. Vertical parallel notches were made at the base of the heads.

Just below the neck, the central figure has an oval hole with a diameter of 0.5 cm. Another hole, oval in shape and measuring 1.2 × 0.5 cm, is located between the neck and head of the side figure.

Apparently, we have a belt buckle with the lower oval hole intended for fastening the buckle to the belt, and the upper hole for threading the fixing cord. It should be mentioned that according to its manufacturing technique, the buckle is similar to horn pendant found in burial 310 at the cemetery of Sopka-2/4 B, C of the Krotovo culture (Molodin, Grishin, 2016: Fig. 169, 26 ).

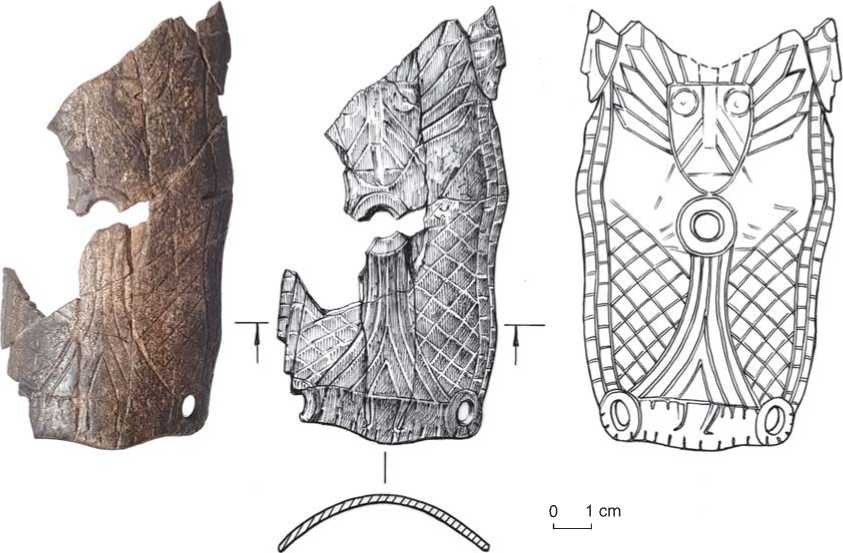

Onlay (burial 1). This item of sub-rectangular shape was made of a plate of mammoth ivory. It is convex along the longitudinal axis, with carefully processed rounded edges bearing a symmetrical wavy contour (Fig. 3). Round holes outlined by engraving are located in the

Fig. 3 . Onlay with anthropomorphic representation (mammoth ivory).

corners and precisely in the center of the item. The entire external surface was carefully polished and was intensely covered with engraved lines, while the internal surface was only slightly polished and retained the natural structure of split tusk. The item has been preserved in fragments. Its length is 11.7 cm; width is 6.0 cm, and thickness is 0.3 cm.

The subject of the engraved representation parallels the image of the mask on the belt buckle described above. An anthropomorphic figure is in the center of the composition. A mask of sub-triangular shape with the engraved denticulate ornamental décor, radially diverging rays of the headdress of feathers as on the buckle described above, was depicted in the upper part of the item. Its chin rests on the hole in the center of the artifact. The eyes can be barely discerned. The contour of the mouth was not marked. Two pairs of parallel diagonal lines of the “tattoo” extend down on both cheeks from the area of the nose, which is not shown. The lower part of the gracile anthropomorphic figure is depicted as a long skirt in the form of forked bird’s tail. The arms are not shown. In the upper part of the item, on the right, there is a profile image of a realistic face, the features of which were modeled more carefully: straight nose, round eye, nasolabial folds, two pairs of lines of the “tattoo” were rendered in relief. The parallel with the subject on the belt buckle described above suggests that this character must have had a headdress and symmetrically located profile image of the face on the left, but these parts of the artifact have not survived.

Paired bands with transverse notches, which enclose the central image in a kind of frame are depicted along the sides of the item. A mesh-like ornamental décor reminiscent of beaver’s tail as its style was made between the bands and central figure.

The onlay was found in the same complex with the belt buckle described above, tightly adjoining it in a single spatial orientation and partially covering it. These artifacts were discovered with their decorated sides up. Moreover, the images of anthropomorphic figures were located “head to tail”: the mask on the onlay was in the area of the legs of a anthropomorphic figures on the belt buckle. The convex onlay lying on the flat belt buckle became deformed and has survived in a fragmented state.

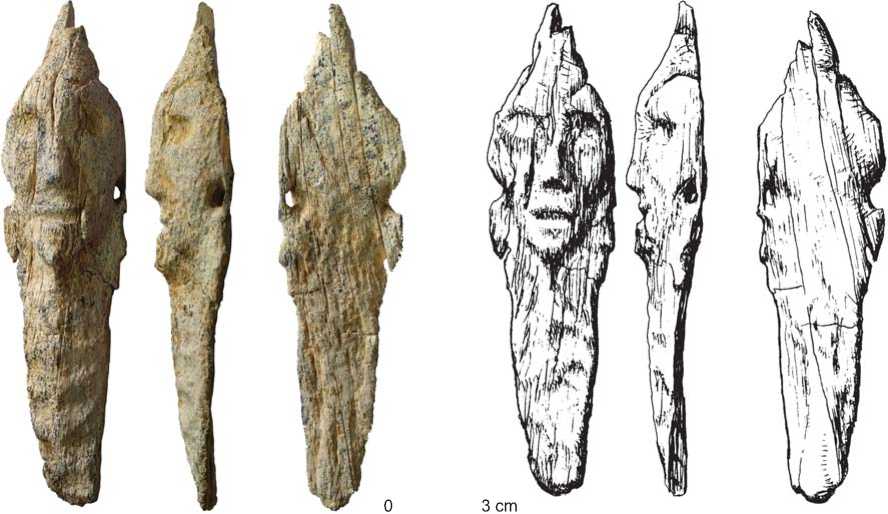

Partial anthropomorphic figure (burial 5). This artifact was made of elongated ivory flake and represents a sculptural image of a human face (Fig. 4). According to the classification proposed by S.V. Ivanov (1970: 26), this is a high relief intended for viewing from the front (as opposed to the so-called sculpture in the round). The item has elongated diamond-like shape, flat-convex cross-section, and slightly curved profile. The longitudinal edges are rounded, subparallel to the long axis, and gradually narrow from the line of the eyes to the lower and upper parts of the figurine. The length of the item is 143.8 mm; its width in the area of the head is 36.7 cm; width in the middle part is 35.1 cm, and width in the lower part is 16.7 mm; thickness is 22.7, 17.6, and 7.3 mm respectively. The volume of the sculpture is 34.86 cm3.

Fig. 4 . Partial anthropomorphic figure (mammoth ivory).

The high relief of the human’s head conveys the facial features, which make it possible to recognize a Caucasian. The general outline of the face is diamond-shaped. The eyes are open, widely set, of ellipsoid shape, 8.7 and 7.2 mm in diameter. The forehead is slightly convex; the nose is straight and voluminous, with the rounded base; recessed nasal-labial folds are evident; the chin is pointed. The mouth is half open, slightly asymmetrical, and wedge-shaped in profile. Two bi-conical openings, oval in shape (4.13 and 2.09 mm in diameter), are at the base of the nasal septum at the longitudinal edges of the artifact. With a considerable degree of certainty, we can speak of a pointed headdress. The head was set on a fairly long shaft (stylized body), on which two rows of rounded indentations 7.5–11.0 mm in diameter, which may be the elements of ornamental décor, are clearly visible.

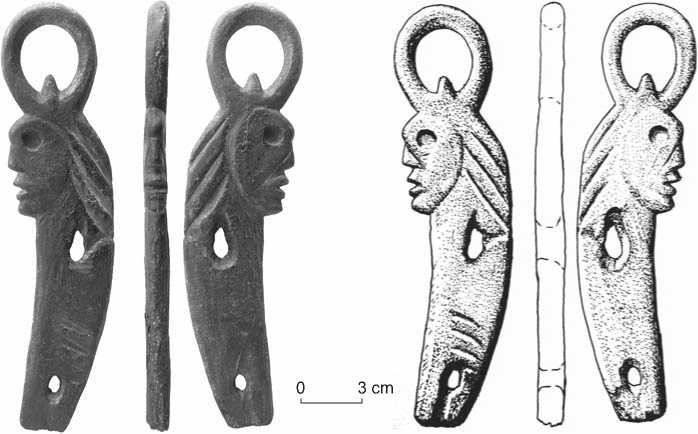

Belt buckle with anthropomorphic representation (burial 5). Its obvious position in the burial in situ next to the left forearm of the person undoubtedly indicates that the belt was placed into the grave in unbuckled way, which has been repeatedly observed in the materials of the contemporaneous Odinovo culture (see (Molodin, 1994)). The item is flat, double-sided (Fig. 5). Only the head was rendered in a realistic manner. While the item was not very thick, it was carefully treated like a sculpture in the round. Two profile images were executed with greatest care, although the front view is also quite discernable, despite a certain degree of stylization. The male was depicted with open mouth and full lips shown in relief. The most careful treatment was given to large round eyes emphasized by engraving. The nose is slightly upturned and voluminous; a tattoo is clearly shown on both sides in the form of slanting little lines in relief. Slanting lines render long hair. A large round ring into which the waist belt was threaded, crowns the head of the figure. A pointed spike-clamp may possibly imitate a pointed headdress. At the top and bottom, the body of the buckle has two large oval holes for its attachment to the belt. The length of the artifact is 19.6 cm; width is 4.9 cm, and thickness is 0.9 cm. The material is burl and resin.

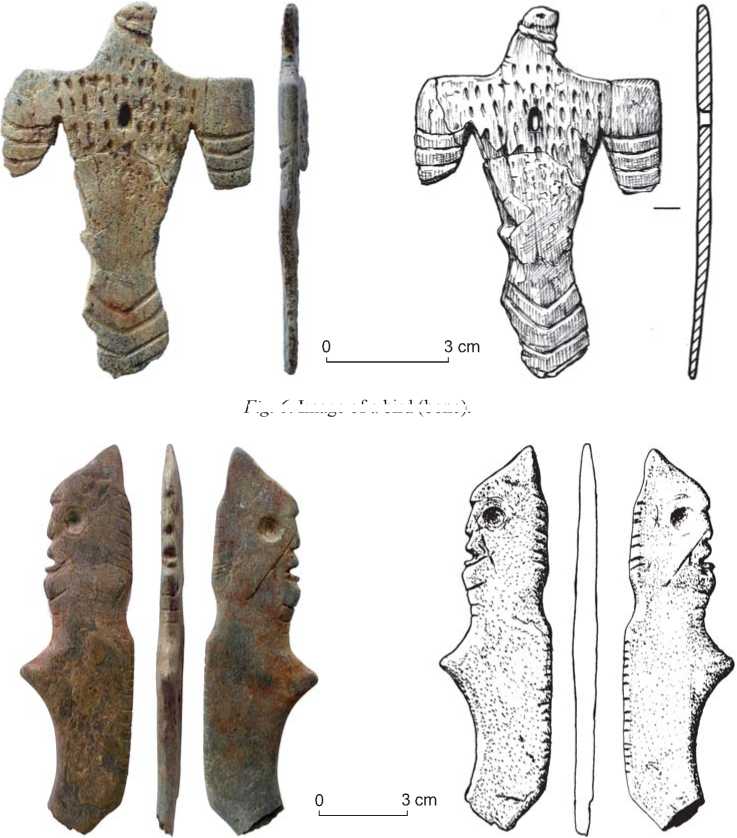

Figure of a bird (burial 6). The product is flat and single-sided. The figure was made in a realistic manner (Fig. 6). The bird was depicted in the heraldic pose, frontally, with its wings spread. The head is turned to the left. The beak was broken off, but apparently it was small in size. Horizontal lines and notches on its chest, wings, and tail rendered the bird’s feathering. Judging by the exterior view, the image was based on the saker falcon ( Falco cherrug J.E. Gray , 1834 ), representative of the local ornithological fauna, daytime predator of the Falconidae family of the Falconiformes order*. An oval hole was on the chest of the figure. Apparently, this item was either sewn on clothing or was suspended using this hole. In the grave, it lay in the center of the chest of the deceased. The length of the item is 8.9 cm, width is 5.8 cm, and thickness is 0.3 cm. The material is bone.

Anthropomorphic figure (burial 6). This is profile, double-sided, and flat (Fig. 7). The head and upper body

Fig. 5 . Belt buckle with anthropomorphic representation (burl, resin).

Fig. 6 . Image of a bird (bone).

Fig. 7 . Anthropomorphic figure (slate).

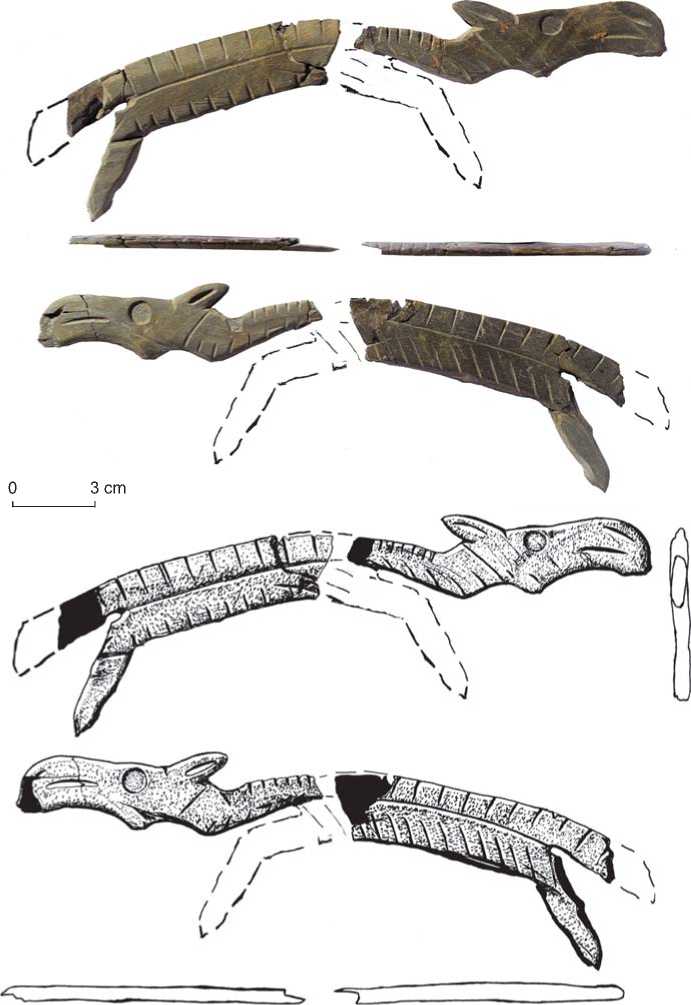

Fig. 8 . Elk representation (slate).

of a person (probably male) are represented. The head wearing pointed headdress was depicted in a realistic manner. Part of the body and possibly the arm are expressed in a stylized way. The head was processed like the sculpture in the round, although owing to the specific properties of the raw material, it is perceived as two profile images. The front view is also perfectly discernable. The man is depicted with his open mouth; full lips are emphasized in relief. The nose is small and straight. Drilling from the opposite directions created round eyes. The hair is shown with symmetrical slanting notches. On one side, the notches were made on the chin, which suggests the presence of a beard outlined by a grove in relief. Slanting lines (probably a tattoo) go down from the nose. Several horizontal notches were made on the neck under the chin. The body of the person is covered with parallel horizontal lines on its narrow end. Their rhythm with equal and unequal intervals suggests the presence of a calendar system, especially since this object was clearly of non-utilitarian purpose. The length of the artifact is 12.7 cm; width is 3.8, and thickness is 0.4 cm. The material is slate.

Figure of an elk (excavation pit, grid 101/364). The item was broken into two fragments. The figure is flat, double-sided, and was gracefully made in a realistic manner (Fig. 8). Elongated oval ears were executed with great care. Drilling with a tool with a flat working edge resulted in large round eyes on long muzzle. Arcuate notches rendered its nose and mouth. Two parallel lines descending from the base of the nose to the protrusion under the throat (dewlap on the neck) are barely visible near the eye (as in the masks described above). The body is elongated compared to the limbs, which might have been caused by the size, shape, and material of the blank. Slanting and vertical carved lines on the figurine could indicate both animal hair and conventionally rendered ribs (“skeletal” style). The latter suggestion is supported by the length of the notches, their general orientation towards the longitudinal line dividing the body in half, and the very presence of that line. The figure retained one hind limb; the lower part of which was broken off, but not lost. An oval hole was partially preserved between the leg and body. The length of the artifact (as a whole) is 22 cm; width (along the body) is 2.9 cm, and thickness is 0.4 cm. The material is slate.

Pictorial parallels and interpretation of representations

Tri-partite compositions of anthropomorphic figures, as the composition on the buckle from burial 1, are common among ancient representations of Siberia. The most archaic variants can be seen on the petroglyphs of the Okunev culture in the Middle Yenisei River region. A large composition of that kind is present at the Shalabolino rock art site, where a large “sun-headed” mask was depicted in the center, and gracile profile anthropomorphic figures were represented to the left and to the right of the central image (at the edges of the plane), with the only difference that the figures did not have multiple rays, but high pointed and loop-shaped headdresses (Pyatkin, Martynov, 1985: Fig. 68). Anthropomorphic figures with masks have been found on the walls of the Proskuryakov Grotto in the eastern spurs of the Kuznetsky Alatau, where they were more compactly arranged in a row (Esin, 2010: Fig. 14, 3). The central Okunev mask is flanked by anthropomorphic figures at the Ashpa rock art site in Khakassia (Leontiev N.V., Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Fig. 23, 1). We can observe numerous combinations of several anthropomorphic figures wearing various masks both on the Samus pottery and on the walls of the burial chambers of the Karakol culture in the Altai (Esin, 2009: Pl. 1, Fig. 57, 76, 7; 98, 8; 106, 2, etc.; Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 13, 4; 33, 41, 106, etc.). An interesting composition of the Bronze Age appears at the Maya rock art site in Yakutia, where masks were placed above the spread arms of the central masked image; the right mask had the headdress with multiple rays (Okladnikov, Mazin, 1979: Pl. 52). Similar images sometimes occur on the Samus pottery (Esin, 2009: Pl. 1, fig. 93, 128), Karakol paintings (Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 13, 1; 14, 33, 95; 121, 7), and at the Sagan-Zaba rock art site of the Bronze Age on Lake Baikal (Okladnikov, 1974: 73, pl. 7). In our case, disproportional long arms of the central figure can be explained by the presence of some pointed objects in place of the hands, resembling leaf-shaped “fans” in the hands of the Karakol anthropomorphic figures (Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 139, 1–3).

Despite the identical eye design, “tattoo” motifs, and framing of multiple rays, the heads of the central and side figures were depicted in different styles. In addition to the view, they differ in the degree of realism manifested by the images. In addition, they have different outlines of the facial part. Framing of multiple rays is typical of many masks known from the steles, petroglyphs, and pottery of the Okunev culture (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 63, fig. 8, 6 , 7 ; Leontiev N.V., Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Fig. 5; 7, 6 ; 20, 1 , 3 ). The figures under consideration are also related to the Okunev images by the manner of executing rounded eyes, lines of the “tattoo”, and pictorial features of mask outlines.

Relatively recently, “sun-headed” characters were identified at the Tom rock art site (Miklashevich, 2011: Fig. 4–6). They also appear on the Samus pottery (Esin, 2009: Pl. 1, fig. 135, 1 , 2 ). Drawings of the Early to Middle Bronze Age on stone slabs of funeral structures of the Karakol culture in the Altai Mountains (Kubarev, 1988: 31, fig. 19) show great similarity in terms of rendering the headdress of feathers. Thus, a human figure with rays or feathers adjoining his head and horizontal line made with red paint on the face, separating its lower part from the upper part, appears on slab No. 1 from kurgan 2 at the Karakol cemetery. Generally, the figure, depicted in outline, is graceful and elegant, which brings it closer to the central figure on the buckle under discussion. Some similarity between the central figure on the buckle is also observed in the anthropomorphic image on a bone plate found in the grave at the Korablik I kurgan in the northeastern Altai Territory (Grushin, Kokshenev, 2004: 42, fig. 4, 1 ), particularly in the headdress (or representation of hair) in the form of rays or feathers, half-open mouth, and bands on the face, made by carved lines.

Profile images of anthropomorphic masks with open mouths, rounded eyes, and a distinguished nose area appear on stone sculpture from the settlement of Samus-4 (Esin, 2009: 453, pl. 3, 6, 7), sculptures of the Okunev culture (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 145, pl. XXXVI, 35–37; XLVIII, 96; LIV, 138, 141), and Karakol petroglyphs of Beshozek (Savinov, 1997: Fig. 6, b). However, these images practically lack the headdress of feathers, which points to the uniqueness of the images on the buckle from the cemetery at the Tourist-2 settlement. The headdress might have been depicted in highly stylized manner in the form of a “crest” in anthropomorphic sculptures from the sites of Samus IV and Karakan (Borodovsky, 2001; Esin, 2009: Fig. 45, 1–3), and was more realistically shown in a profile figure with the predator mask on a slab of a stone box from burial 5 at the Karakol cemetery (Kubarev, 1988: Fig. 45).

Another feature of the anthropomorphic figures on the buckle from Tourist-2 is the presence of pronounced neck, which is not typical of the above images in the petroglyphs of the Altai and Khakass-Minusinsk Basin. At the same time, this feature is an integral part of the majority of anthropomorphic figures with masks appearing on the Samus pottery (Esin, 2009: Fig. 28). The neck is also emphasized in the characters on the petroglyphs of the Baikal region and Lower Angara region (Okladnikov, 1974: Pl. 4–10, 25, 26; Zaika, 2013: Pl. 112, 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 13 , 14 , 16 ; Pl. 119, 1 , 5 , 16 ).

Paired, sometimes symmetrical, placement of mythical predators appears on the Okunev petroglyphs (Studzitskaya, 1997: Pl. II, fig. 1; Leontiev N.V., 1997: Fig. 1). On statues and steles, they usually also occupy the lower position (Leontiev N.V., Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Fig. 103, 111, 140, 143, 157, 159, 194, 277, 282). Lateral “sun-headed” anthropomorphic figures on the buckle from the cemetery at Tourist-2 seem to grow out of the open mouths of predatory fish. The subject of devouring or throwing up of anthropomorphic characters, “sunheaded” masks, or solar symbols by mythical predators is well represented on the petroglyphs of the Okunev culture (Ibid.: Fig. 47, 102, 194, 208, 222, 226, 282, 288; Savinov, 2006: Fig. 16, 2 ; 17, 1 , 2 ; 19, 2 ; Studzitskaya, 1997: 255–256, pl. I, fig. 1, 2; Tarasov, Zaika, 2000: Fig. 1, 4). This fact, along with the aggressive nature of the chthonic images, suggested some scholars to regard them as the embodiment of the generative principle, to consider them as demiurges—creators of the Universe and lords of the three worlds (Pyatkin, Kurochkin, 1995: 72; Pyatkin, 1997; Savinov, 1997: 202–203; Tarasov, Zaika, 2000: 187–188). In this context, the images on the belt buckle from burial 1 may reflect the ideas of the ancient inhabitants of the Ob region concerning the universe. The vertical model of the world order is clearly visible: heads of the figures, which are framed by the “sun” plumage, can be associated with the upper realms; trunk and arms, with the middle-earthly world; while the images of predatory fish and lower limbs of anthropomorphic images joined to them, with the lower level of the universe (underground/underwater world). Along with this, we can observe here a more archaic, horizontal principle of world order, syncretically inscribed into the general subject. The frontal anthropomorphic figure symbolizes the center of the universe, while the side figures may indicate the binary spatial opposition: south/east–north/west.

Another distinctive aspect of images on the belt buckle is realistic style of anthropomorphic images, and their naturalistic manner of execution. Apparently, while solving the problem of the visual rendering of abstract meanings, and harboring ideas about the world order and about spirits/deities, the ancient artist used the images of costumed characters (performers of rituals and mythological scenes) who modeled them. The practice of portraying costumed masked figures (participants in the rituals) was widespread in the Karakol funerary paintings and Okunev petroglyphs (Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 128– 130, 134–137, 139, 209; Leontiev N.V., Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Fig. 15, 5 , 6 ; 20, 1 ; 23; Lipsky, Vadetskaya, 2006: Pl. XVI, XIX–XXII).

The anthropomorphic figure made of mammoth ivory reveals a certain similarity with the bone mask from burial 677 at the Sopka-2 cemetery in the Om River region in the Baraba forest-steppe (Molodin, 2001: 58, fig. 37, 3 ). Here, the face is also shown in frontal view; eyes and mouth are rendered with oval indentations; the mouth is half-open; there is a cone-shaped headdress on the head. This item has special loops with rounded holes for attaching to clothing (Ibid.: 103). The artifact from the Tourist-2 cemetery also has rounded holes for fastening. Such images of head and face were typical of the Neolithic to Early Metal Age in both Western and Eastern Siberia (Ibid.). Notably, according to the stylistic and iconographic features, the head of the figure from mammoth ivory shows a striking resemblance to the realistic masks of sculptures and miniature pestle-like figures, which E.B. Vadetskaya united into a separate group of anthropomorphic images of the Okunev culture (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 48–49, fig. 4, II). Moreover, one of the masks in relief from that group is crowned with the cone-shaped pommel (Ibid.: Pl. LIV, fig. 141). The material from which the figure was carved corresponds to the tradition of using bone remains of the paleofauna in the bone carving of the Late Bronze to Early Iron Ages, which was widespread in the southwestern Siberia and especially in the north of the Upper Ob region in the vicinity of Novosibirsk (Borodovsky, 1987; 1997: 104–111).

The practice of representing partial anthropomorphic figures without limbs (usually the lower) was widespread in the art of geographically close cultures of the Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age, and in later periods. These include pestle-like sculptures, “small idols” in petroglyphs, and wedge-shaped anthropomorphic figures on ceramic vessels (Savinov, 1997: 204). The figures of “small idols” have been found in burials in the Altai (Grushin, Kokshenev, 2004: Fig. 4, 1 ), Angara region, and Baikal region (Studzitskaya, 2006: Fig. 1, 8–10, 12; 2011: Fig. 11, 13; Okladnikov, 1976: Pl. 64, 1 ).

Another interesting object of portable art that was found in the cemetery at Tourist-2 is a flat bone figure of the bird in heraldic form from burial 6. What we have here is an indisputable evidence of the emerging heraldic interpretation of the image of the predatory bird already in the Early to Middle Bronze Age, which in itself can hardly be overestimated. A similar pictorial tradition appeared almost simultaneously in the 6th–5th centuries BC in the objects of movable art of the Volga-Kama region, Urals, and Western Siberia, where it was further developed and reached its peak in the Early Middle Ages (Chemyakin, Kuzminykh, 2011: 70–71, pl. 1–19). The stylistic similarity of our find with a bronze bird figurine from the Usa River (Southern Urals) (Kosarev, 1984: 187, fig. 25, 14) can be observed.

In the movable art of the earlier periods in Siberia, ornithomorphic images were usually represented by bone or stone figurines of waterfowl (Kosarev, 2008: 91–92). An exception is a stylized frontal image of a bird on a Chalcolithic vessel found in the settlement layer at the Borovyanka-7 cemetery (Omsk region) (Chemyakin, Kuzminykh, 2011: 47, fig. 1). The find from burial 6 under discussion is the earliest known “heraldic” image of a predatory bird appearing in the small plastic art in Siberia. Based on the sources available today, it marks the initial stages of the emergence of this artistic tradition, which developed (both in its form and apparently in its contents) in subsequent cultures.

Sculptures of elk have widely appeared in Eurasia since the Neolithic (Kosarev, 1984: 194). This image also dominated the cave art of the taiga inhabitants of Siberia. A realistic bone figurine of elk found at the Elovka settlement (Tomsk region of the Ob) (Ibid.: 191, fig. 2) shows remote similarities to the image of the elk discovered at Tourist-2. The pommels of bone spoons, rod-staffs, and pendants in the form of elk heads have been regularly found at the Neolithic sites of the Baikal and Angara regions (Studzitskaya, 2011: 39–49, fig. I). Almost complete elk figurines carved from bone were found in a Serovo burial at the Bazaikha site (Okladnikov, 1950: Fig. 90).

Emphasized round eyes, specific features of rendering the head part of the elk figurine (ears pressed to the head, robust upper jaw, marked line of the mouth, dewlap on the neck, etc.) from the cemetery at the Tourist-2 settlement have close parallels in the petroglyphs of the Angara style in the south of Central and Western Siberia (Sovetova, Miklashevich, 1999: 55–59, pl. 2, 3, fig. 5) and are almost identical to the representation of the elk head from a Neolithic burial at the Bazaikha site.

Anthropomorphic items from burials 5 and 6 might have had a utilitarian purpose during the life of their owners. Two stylized facial outlines in the upper part of bone rods, which with a certain degree of probability could have been used by the carriers of the Kitoy culture as piercing tools/hairpins, and a bone-piercing tool crowned with the representation of a human head from a Serovo burial near the village of Anosovo on the Angara

River (Studzitskaya, 2006: Fig. 1, 8; 2011: Fig. II, 13, 7) can be mentioned as examples. Stone boot-shaped item/ whetstone with the anthropomorphic pommel found in the vicinity of Tomsk, which can be correlated with the Samus culture (Esin, 2009: 111, pl. 8), and the Okunev small sculpture from the vicinity of the Charkov Ulus in Khakassia (Leontiev N.V., Kapelko, Esin, 2006: 9, fig. 121), which, with some imagination, can be interpreted as a fishing sinker (Zaika, 1991: 33), can be considered to be the stone items of that category.

According to their stylistic and iconographic features, profile double-sided representations of the human face on these items are similar both with each other and with both the side figure on a buckle from burial 1 and with the “small idol” from burial 5 (in profile view). Each of them has large round eyes, a straight nose, and a half-open mouth; forehead, lips, neck, and chin are more or less pronounced; diagonal lines of the “tattoo” are shown. The outline of the face is emphasized with a semicircle, and the lines of hair/feathers are also adjacent to it at the side on anthropomorphic figure on the buckle from burial 5 and the side character of the multi-figured composition from burial 1.

Distinctive facial features find numerous parallels in stone movable art of the Samus culture, as well as Okunev and Karakol petroglyphs mentioned above. Pointed hats are typical of the anthropomorphic figures in Okunev cave paintings, but the headdress is higher there (Kubarev, 2009: Fig. 135, 4–6 ; 136, 1 , 2 ). Frontal masked figure on a slab from the cemetery near the village of Ozerny (Ibid.: Fig. 13, 4 ; 147, 7 ) has the headdress of comparable size. Ring-shaped/loop-shaped headdresses have been found among the Okunev images, but they are more typical of the Karakol profile anthropomorphic figures (Ibid.: Fig. 130, 1 , 3–11 ; 131, 1 ). In ritual scenes, these masked characters convey the images of spirit-deities.

Conclusions

The objects of portable art found in the burials on the territory of the Tourist-2 settlement are unique both individually and as a general set, although they share a common tradition of rendering individual details of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery. Considering the circumstances of their discovery, as well as the subject-oriented and iconographic features of representations, these artifacts should be attributed to the category of sacred objects associated with cultic practices. Despite the different nature of the artifacts, they are united not only by the close proximity of the burials, but also by the common pictorial traditions employed while representing the characters.

Anthropomorphic images may have realistically reproduced the appearance of real characters. Their common ethnic and social affiliation may have been emphasized by a similar style of tattoo. However, the faces of the figures are distinguished by stylization and certain conventionality—the ancient artist was clearly guided by the established pictorial canons when he was creating the images, and used stylistic and graphic techniques that were typical of the indigenous artistic traditions. The style is well distinguishable; it is clear and recognizable. The general principles of executing anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images can be observed using the example of rendering eyes, which are identical in our elk figurine and in a number of masks not only in terms of their shape, but also in technical parameters of execution.

Theriomorphic and ornithomorphic figures may reflect totemic and animistic views rooted in the Neolithic and are very common for the ancient population of the forest-steppe zone of Siberia. Anthropomorphic imagery may reflect the cult of the ancestors and early forms of shamanism. Multi-figured composition from burial 1 has a more sophisticated semantic content; it illustrates the basic concepts of worldview and mythological nature.

The works of portable art found at Tourist-2 fully comply with the artistic tradition of the Early to Middle Bronze Age in the southwestern Siberia. However, distinctive nature of the complex of finds and their archaeological context suggest that they may represent the previously unknown “Krokhalevka” style in fine art of the peoples of Siberia, which reflects certain autochthonous traditions in spiritual culture. The authors of this study are aware that both attribution of the described items and suggestion concerning a special “Krokhalevka” style are debatable. The proposed name of the style given by the archaeological context of the finds requires additional discussion and argumentation, especially when discovering new objects of portable art of the Middle Bronze Age in the southwestern Siberia. This may well become a topic for a separate study.

The style, which can be preliminarily designated as the “Krokhalevka” style, might have emerged on the local Neolithic basis. However, judging by the well-known visual parallels, its development happened with the noticeable influence of the territorially close Okunev, Karakol, Samus, Krotov, and Odinovo cultures of the Early to Middle Bronze Age. Taking into account the common subject matter and stylistic correspondences with the examples of the Kulai cultic casting, it should be assumed that the “Krokhalevka” pictorial traditions undoubtedly stood at the origins of the Kulai art, which found its clear expression in the objects of metal movable art (Chindina, 1984: Fig. 18, 7, 10 ; Chemyakin, 2013: Fig. 1, 49 ; Yakovlev, 2001: 212; Esin, 2009: Fig. 72, 2–5 ; Polosmak, Shumakova, 1991; Leontiev V.P., Drozdov, 1996: Fig. 5; Kosarev, 2003: 256, fig. 56, 58; 257, fig. 60), and individual iconographic details, which found their further development in Siberia in the cultures of the

Middle Ages (Soloviev, 2003: Fig. 45, 108, a ; Kardash, 2008: Fig. 7, 1 ; Trufanov, Trufanova, 2002: Fig. 1; Oborin, Chagin, 1988: 61, 173, Fig. 148; Zaika, 1997: 99, Fig. I, A, 2, 7 ).

Acknowledgement