Old Turkic statues from Apshiyakta, Central Altai: on female representations in Turkic monumental art

Автор: Kubarev G.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145300

IDR: 145145300 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.1.093-103

Текст статьи Old Turkic statues from Apshiyakta, Central Altai: on female representations in Turkic monumental art

The range of graphic and statuary monuments of the Ancient Turkic period in Central Asia includes a category of original images and compositions where one of the main characters represents a female wearing a threehorned headdress. These images mostly show one and the same scene, depict the same ethnographic realities, and possibly have a common meaning. The famous Kudyrge boulder with an engraved genre scene is one of the most well-known monuments of this kind. Similar compositions have been reported from Bichiktu-Bom petroglyphs in the Russian Altai, engraved images on the horn comb from Suttuu-Bulak burial ground in Kyrgyzstan, an Ancient Turkic statue and rock-image from the Kogaly locality in Kazakhstan, and a figurine from the Khar-Yamaatyn-gol River valley in the Mongolian Altai. The present author was lucky to discover two statues in the Russian Altai, bearing similar images. One of these statues is

Description of finds

In the 2011 field season, the Chuysky team of the IAE SB RAS Altai Expedition carried out an archaeological exploration of the Chuya River valley on the territory of the Ongudaysky District of the Altai Republic. Among others, a funerary complex of Apshiyakta I was investigated, located on a high fluvial terrace on the left bank of the dried Apshiyakta stream’s mouth. The site is situated on the left bank of the Chuya River, opposite the well-known petroglyphic site of Kolbak-Tash I (Fig. 1). The funerary complex comprises 61 items. Two adjoining Ancient Turkic enclosures (No. 54 and 55) are situated separately (Fig. 2).

Enclosure 54 is 2.0 × 2.5 m in size and 0.2 m high. Its eastern wall is preserved better than the others, which are almost invisible. The structure is heavily sodded, and the stone filling can hardly be seen.

Fig. 1. Map showing location of Apshiyakta.

Close to the eastern wall of the enclosure, a statue is installed*, made from greyish light-blue chert. The size of this object is 135 × 18 × 19 cm. Upon cleaning of the frontal stone surface from moss, the facial image was noted in the upper part of the stone (Fig. 3; 4, 1 ). The image is rather schematic. The lower face-outline is shown with an engraved line forming an obtuse angle; and nose and cheekbones with curved lines, whose lower ends adjoin the mouth-outline. The eyebrows are outlined, and the eyes are not shown; yet they are implied. The unworked subtriangular upper part of the stone might have symbolized a high headdress.

Below the first face, on the same facet, another one was discovered, which was partially sodded. This image is highly schematic, too. Cheekbones and nose are depicted with two separate engraved lines, the mouth is triangular. The image shows a three-horned headdress typical of women’s attire (see Fig. 3; 4, 1 ). Over the cheekbones, on the forehead (?) or on the headdress, two dots are observed.

Enclosure 55 adjoins enclosure 54 at the north, and possibly shares a wall with it. In its characteristics, enclosure 55 is close to the funerary structure described above. The enclosure is 2.8 × 2.8 m in size, and 0.2 m high. Its eastern wall is preserved better than other walls. The structure is heavily sodded; stone filling is represented only by few large boulders.

Close to the eastern wall of the enclosure, an anthropomorphic statue is installed, made of light grey chert. The size of the object is 75 × 33 × 14 cm. The upper part and the frontal surface of the stone have been broken off, probably in antiquity. However, the remaining engraved lines suggest that originally there were also two faces here (see Fig. 4, 2). This is evidenced by the lines of the lower part of the face, mouth, and eyebrow (?) of the upper face-image, and also by the general outline of the lower one.

Ancient Turkic and Kimek-Kipchak female statues: history of study

As is known, Turkic statues in Eastern and Western Central Asia were dedicated mostly to male warriors. Female statues produced by Ancient Turks and Kimek-Kipchaks have been discovered primarily in Semirechye and Eastern Kazakhstan (Sher, 1966: 22; Charikov, 1980; Ermolenko, 2004: Fig. 12, 2 ; 15, 1 ; 63, 1 , 3; and others). They represent two separate groups of images, greatly distinguished by their style

*A preliminary report on Apshiyakta statues has been published elsewhere (Kubarev, 2014).

Fig. 2. Ancient Turkic funerary enclosures in Apshiyakta. View from the east.

and by the depicted sex features, culture-specific items, etc. The Kimek-Kipchak female sculptures significantly outnumber those attributable to Ancient Turks.

The first small group of statues includes sculptural representations of women wearing three-horned headdresses. These were discovered in Semirechye and dated to the Ancient Turkic period, i.e., the 6th– 10th century (Fig. 5, 6) (Akhinzhanov, 1978: 67; Ermolenko, 1995: 55; Tabaldiev, 1996: 82; and others). Apart from the headdress, such statues often showed images of other elements of clothing (triangular lapels of caftans, full sleeves, earrings). The depicted women hold a jar in their right hand, or both hands. They are distinguished from the male statues by their lack of representations of mustache, beard, or weapon. The stylistic features of their rendering of facial traits correspond to those of the Ancient Turkic statues: eyebrows and nose are shown with a T-shaped relief cordon, eyes are large, etc. Sculptures with representations of the three-horned headdress were placed close to Ancient Turkic funerary structures, often near the adjoining Kudyrge-type enclosures.

Y.A. Sher (1966: 26) determined approximately one third of the 145 sculptures discovered in Semirechye by the 1960s to be images of characters whose sex is unclear. They show no beard, mustache or weapon. V.P. Mokrynin (1975) was perhaps the first who classified the Semirechye statues with three-horned headdresses as a separate group, and proposed their interpretation as female images. S.M. Akhinzhanov (1978: 74) argued that the custom of representing headdresses of this type was imported by

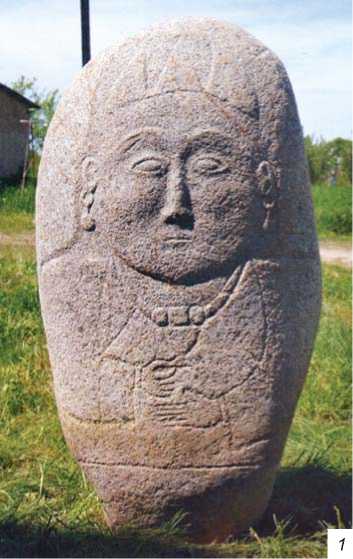

Fig. 3. Statue representing male and female images, placed at enclosure 54.

20 cm

20 cm

Fig. 4. Drawing of facial statues.

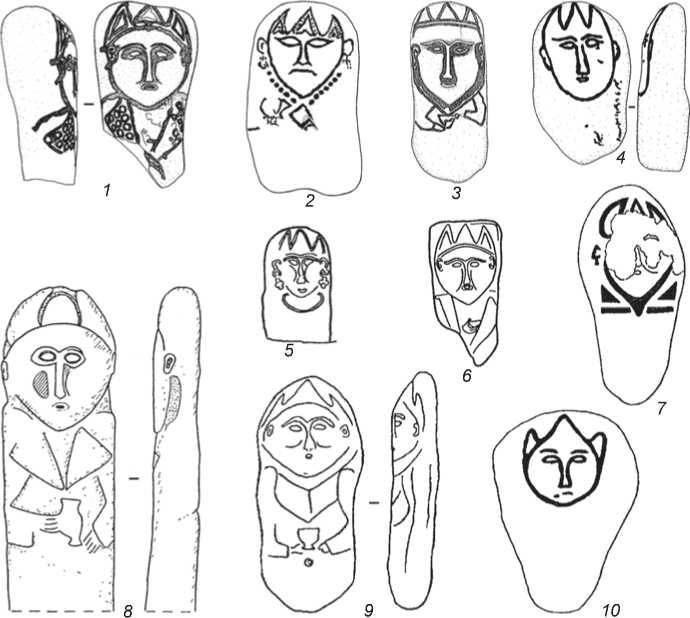

Fig. 5. Images of women wearing three-horned headdresses from Semirechye.

1–4 – Burana, Kyrgyzstan (after: (Tabaldiev, 1996)); 5 , 6 – Kyrgyzstan (after: (Sher, 1966)); 7 , 9 , 10 – Kochkor and Kara-Kuzhur valleys, Kyrgyzstan (after: (Tabaldiev, 1996)); 8 – Lake Balkhash, Kazakhstan (after: (Ermolenko, 2004)).

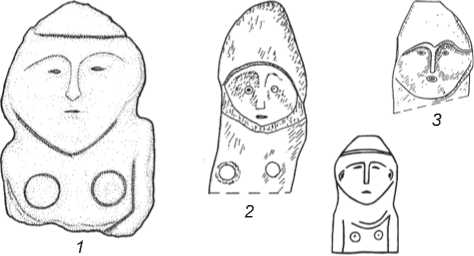

Fig. 6. Female statues with representations of three-horned headdresses.

1 – Chuya valley, Lake Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan (after: (Tabaldiev, 1996)); 2 –Karatau, Kazakhstan (after: (Dosymbaeva, 2006)).

Turkic tribes who migrated here from Altai. The earliest of such images, like that on the Kudyrge boulder, he dated to the 7th–8th century; while generally, he considered these images typical of the 9th–10th century, and attributed them to the Kimek-Kipchak tradition (Ibid.).

The second, more numerous, group is represented by Kimek-Kipchak female statues. They differ considerably from the Old Turkic images in the stylistic features of the facial representation (small eyes and mouth shown as depressions, various styles of rendering nose and eyebrows, etc.) and by other depicted elements or attributes (Fig. 7, 1–5 ). Elements of clothing are usually not shown on such statues. Female breasts are depicted. These statues often represent a woman holding a jar with both hands at her stomach (Fig. 7, 5 ). As compared to the Ancient Turkic sculptures with mostly individual and personified facial features and clothing details, the Kimek-Kipchak images are schematic. Probably the Kimek-Kipchaks depicted a generalized image of an ancestor or a progenitrix, while the Turks represented real, formerly living women.

In those cases where the original placement of the Kimek-Kipchak statues is known, this place is usually close to (or in the center of) the so-called sanctuaries (rectangular stone enclosures-piles, mounds, etc.) (Ermolenko, 2004: 34–37). Y.A. Sher (1966: 46, 61, fig. 15) and A.A. Charikov (1986: 87–88, 101) dated these statues to the 9th–early 13th centuries, and correlated them with the Cuman stone stelae (“babas”). Attribution of such stelae to the Kimek-Kipchak tradition, and their dating to the mid-9th–13th centuries, were supported by other researchers (Ermolenko, 2004: 12–13). Kipchak-type statues are spread over the territory from Eastern Kazakhstan in the east to the Southern Urals in the west.

Female sculptures made by the Ancient Turks of Central Asia are also known, but they are quite few as yet. Unlike the Semirechye statues, they were not installed separately at the enclosure, but almost always accompanied male sculptures. Examples of these are the female statue with a shawl; that of Kyul-Tegin’s wife at his funerary site (Zholdasbekov, Sartkozhauly, 2006: Fig. 119, 120, 124, 125); and the female statue at Shiveet-Ulan site (Ibid.: Fig. 39).

The tradition of accompanying male sculptures by female ones (representing wives of the warriors and nobility) has been recognized in the (currently) few examples in the Altai region. For instance, at the funerary complex of an Ancient Turkic noble on the Khar-Yamaatyn-gol River in the Mongolian Altai, near a male statue, the broken base of another sculpture was found. Judging by a number of features, this was a sculpture of a woman, the wife of this noble (Kubarev, 2015). Another coupled male and female statue has been noted in the Makazhan steppe in Kosh-Agachsky District of the Altai Republic. Here, two sculptures were placed at the eastern wall of a simple enclosure. One of them, depicted with a

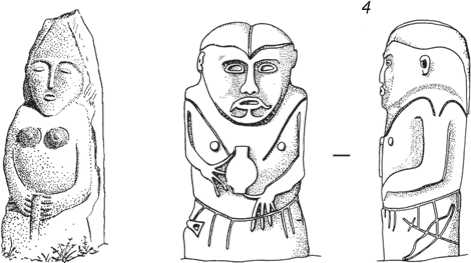

Fig. 7 . Female statues of Kimek-Kipchak tradition with representations of breasts ( 1–5 ), and an Uyghur male statue ( 6 ). 1 – Ailyan, Altai (after: (Hudiakov, Belinskaya, 2012)); 2 , 3 – Aktogaisky District, Karaganda Region, Central Kazakhstan (after: (Ermolenko, 2004)); 4 – Merke, Kazakhstan (after: (Dosymbaeva, 2006)); 5 – Kazakhstan (after: (Margulan, 2003)); 6 – Ergi-Barlyk, Tuva (after: (Kyzlasov L.R., 1949)).

belt and weapon, is a man; while another, highly schematic facial one, might be a woman. These two examples represent the only such finds in the Altai. Furthermore, the possibility cannot be excluded that a considerable number of the facial images without moustaches, beards, and weapons in Central Asia represent females.

Peculiarities of the Ancient Turkic and Kimek-Kipchak female statues are evident, and their distinction among the main bulk of statuary monuments is well-grounded. The majority of scholars support attribution of these statues to the category of female, and their different chronological and ethno-cultural affiliations; yet some researchers put forward another assumption. The most controversial and vulnerable point of view belongs to Y.S. Hudiakov and K.Y. Belinskaya (2012). They attribute the female statue from Ailyan (Fig. 7, 1 ) in Shebalinsky District, the Altai Republic, to the Kurai stage of the Ancient Turkic culture (Ibid.: 128). These authors proposed to identify a separate group of Ancient Turkic female statues, depicting breasts, from Altai, Tuva, and the Upper Ob, and formed corresponding cultural-historical and ideological conclusions that do not stand up to scrutiny (Kubarev, 2012). The Ailyan sculpture represents one of the few Kimek-Kipchak statues discovered in the Gorny Altai, and should be dated to the mid-9th–13th century.

Parallels and semantics of the three-horned headdress

The most specific feature of the Apshiyakta female faces, and also of those from Semirechye, is the headgear with three cogs (see Fig. 5, 6). In the literature, it is most often referred to as a three-horned headdress (Gavrilova, 1965: 66; Sher, 1966: 100; Akhinzhanov, 1978; Tabaldiev, 1996: 69, and others), more rarely, as a three-horned tiara (Kyzlasov L.R., 1949: 50; Dluzhnevskaya, 1978: 231) or a crown (Motov, 2001: 68). Almost all researchers agree that this headdress highlighted the special status of its owner. This detail is important, because its interpretation was regarded as the main argument in favor of iconographic attribution of the character

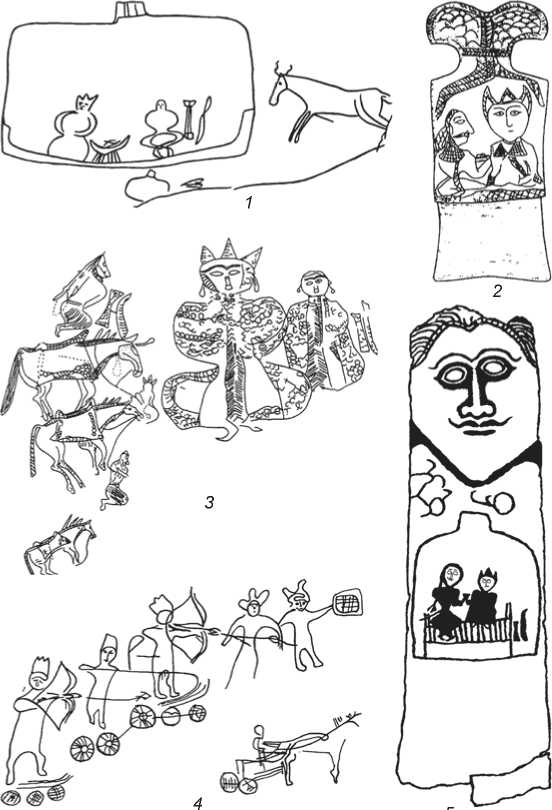

Fig. 8. Genre scenes with female characters in three-horned headdresses. 1 , 4 – rock graffiti from Bichiktu-Bom, Altai ( 1 – after: (Kubarev, 2003); 4 – after: (Martynov, 1995)); 2 – scene on a horn object from mound 54 at Suttuu-Bulak burial ground, Kyrgyzstan (after: (Tabaldiev, 1996)); 3 – scene on the Kudyrge boulder, Altai (after: (Gavrilova, 1965)); 5 – statue from Kogaly, Kazakhstan (after: (Rogozhinsky, 2010)).

wearing a three-horned headdress to the goddess Umay (Kyzlasov L.R., 1949; Dluzhnevskaya, 1978; Motov, 2001; and others) or to a shaman (shamaness) (Akhinzhanov, 1978: 70, 71; Dosymbaeva, 2006: 45; and others)*.

Detailed representations of the three-horned headdress on some Semirechye statues, on a horn object from Suttuu-Bulak (Fig. 5, 7 ; 8, 2 ), and on coins of Western Turkic Khaganate (Fig. 9, 1–3 ) suggest that this headdress was neither a tiara nor a crown, because the central “cog” was shown in projection behind the two rather curved lateral cogs (Kubarev, 2003: 244). Thus, the three-horned headdress had a high cone-shaped protrusion on top and two, often curved, blades at the temples. The headdress was most likely made from some organic material, such as felt. On the detailed images, blades have edging. Possibly, the blades could have been edged with stripes of printed silk, in the same way as the elements of caftan (cuffs, collar, and lower hem).

It is generally recognized that in various chronological periods, the most meaningful piece of attire of the nomads in Eastern and Western Central Asia was the women’s headdresses. Examples include high and complex headdresses of the Pazyryk women, Mongol female headgear bokka, etc. It is likely that they represented some complicated ideological symbols. G.V. Kubarev (Ibid.) and Y.S. Hudiakov (2010: 99–100) have come to the conclusion that the three-horned headdress cannot be regarded as a crown or a tiara, but rather, it represents quite functional women’s headgear.

While the majority of scholars correlate a woman wearing a three-horned headdress with the goddess Umay or a shamaness (shaman), L.P. Potapov proposed a quite different interpretation of the composition depicted on the Kudyrge boulder. According to him (Potapov, 1953: 92), this drawing illustrated written sources narrating the story of the Turkic khagan subduing other tribes as tributaries— “head bowing and kneeling”. The dismounted horsemen kneeled in front of a sitting woman, wearing a three-horned headdress and rich clothing, and an infant (Fig. 8, 3 ). This political and social interpretation of the scene was supported by A.A. Gavrilova (1965: 18–21) and G.V. Kubarev (2003).

*The history of study of the Umay image iconography among the Ancient Turks on the basis of pictorial materials requires special research. The present article does not contain either comprehensive information on this topic nor criticism of the attempts of identification of the possible iconography of this image.

Fig. 9. Western Turkic Khaganate coins from Chach, bearing images of a ruler, and his wife in a threehorned headdress. Photograph by G. Babayarov.

The most fantastic interpretation of the Kudyrge boulder composition was proposed by P.P. Azbelev. He believed that the main character was the Mother of God, while the composition rendered the scene of Adoration of the Magi (Azbelev, 2010: 48–49). This work by Azbelev, who named it a “treatise”, might be not taken seriously, were it not for the publication activity of the author and questionable quality of many of his inferences. Azbelev is not perplexed by the fact that the “baby” from the Kudyrge composition (Fig. 8, 3 ) is rather grown up, judging by the proportions of the body, and most likely a girl (like the main character, she also has an earring in each ear), and also that there were other representation of women in three-horned headdresses with children (Fig. 8, 4 ) that were not accompanied by the kneeled “Magi”. It does not seem necessary to comment on the speculative and unreliable ideas of the “treatise’s” author (Ibid.: 51) about Nestorian sermons in the Altai, about Christian women who became wives of Turks but reserved their Christian faith, and about captive or hired Christian artists.

In sum, available points of view on the characters wearing three-horned headdresses, represented in graffiti and on monumental statues of the Ancient Turks, can be summarized in the four major interpretations.

-

1. Characters with a crown or a tiara represent the goddess Umay (Kyzlasov L.R., 1949; Dluzhnevskaya, 1978; Kyzlasov I.L., 1998; Motov, 2001; and others) or even the Mother of God (Azbelev, 2010). Researchers came to this conclusion on the basis of analysis of Ancient Turkic graffiti, and primarily of the composition on the Kudyrge boulder.

-

2. Characters in three-horned headdresses represent either shamanesses, personifying the cult of ancestors through female lineage (Akhinzhanov, 1978), or shamans (Dosymbaeva, 2006: 45).

-

3. Social and political interpretation of Ancient Turkic scenes with representations of women in three-horned headdresses implies the acknowledgement of the high social status of their owners and a possible reflection of political history (subordination of one tribe to another, etc.) (Potapov, 1953: 92; Gavrilova, 1965: 18–21; Kubarev, 2003).

-

4. A three-horned headdress was broadly used by the Ancient Turks and other Turkic-speaking nomads, and did not imply any high social status of its owner (Hudiakov, 2010: 99–100).

Interpretations 1 and 2 are based mostly on the presence of the three-horned headdress representing either a crown or a tiara, and its possible semantics, and also on representation of the “kneeling” scene on the Kudyrge boulder graffiti. Neither the one thing nor the other can be regarded as a reliable argument in favor of interpretation of the images as those of goddess Umay or a shamaness (Kubarev, 2003). In contrast, all the mentioned arguments (interpretation of three-horned headdress as a functional piece of attire, representation of women wearing such headdress on stone statues, family character of many funerary structures with such statues, etc.) testify to the contrary.

There is another representative series of images of women wearing three-horned headdresses, to which practically no attention was paid. But inclusion of these images in the discussion seems to be important with respect to the topic. It concerns the numerous coupled images of a ruler and his wife on the coins of the Western Turkic Khaganate in Sogdia of the 6th–8th centuries (Rtveladze, 2006: 88–89; Shagalov, Kuznetsov, 2006: 75–76, 79–85; and others). The co-ruling woman is shown there in the three-horned headdress.

One variant of such an image represents the so-called chest-high portrait of a ruler and his wife (see Fig. 9, 1–4 )*. In the foreground (left), the image of a man is shown. He has a broad face with high cheekbones, and long hair falling down his back. The woman is depicted to the right and behind the man. Her face is broad, and she wears a three-horned headdress, whose central “cog” is curved, cone-shaped, and considerably higher than the other two. The reverse shows a tamga surrounded by a Sogdian legend.

Another variant is the representation of a man and a woman sitting in a cross-legged position and facing each another (see Fig. 9, 5–8 ). The ruler’s face is shown in side view; his wife’s face is in front view. The man’s hair is long and falls down to the shoulders; earrings are shown in the ears. He wears a long slim-cut caftan with a broad right-side lapel, which was typical of Ancient Turks; in his left hand, he holds some object (vessel?). The woman wears a high three-horned headdress and a caftan. She holds something in her hands, possibly a vessel. On some coins in this series, the co-ruling woman is shown to be pregnant (Fig. 9, 6–8 ).

Apparently, both coin-types represent one and the same scene: a Turkic ruler with his wife. Despite various interpretations of the Sogdian legends from the coins proposed by researchers, they imply either a representative-governor of the Western Turkic khagan, or a khagan himself (Shagalov, Kuznetsov, 2006: 61, 76).

Notably, more-or-less canonical images of a husband and his wife were popular and widely spread among the Ancient Turks. These images have been reported from numerous petroglyphic sites, grave goods, and stone statues. Therefore, it can be asserted that this scene on coins was popular and clear to the Ancient Turks. Most representative are the images of sitting ruler and his wife (Fig. 9, 5–8 ). These images are absolutely identical to the Ancient Turkic engravings from Altai and Tian Shan. Even the details are basically the same: both man and woman sit in a cross-legged position; she is almost always to the right of him; he sits half-face to her and holds an object resembling a vessel; the woman wears a threehorned headdress, etc.

Chinese written records hold that the Ancient Turkic Khaganate was characterized by a dual power structure: a confederation of several related tribes was headed by two aristocratic families—Ashina and Ashide. The Khagan was descended from the Ashina clan, whose symbol was the sun and whose clan tamga was the image of an argali (wild sheep). His wife ( katun ) was descended from the Ashide clan (Ashtak), which symbol was the moon and the clan tamga was the image of a snake or dragon (Zuev, 2002: 33–34, 85–88).

The most vivid illustration of the marital union between two aristocratic families of Ashina and Ashide is the representation of a ruler and his wife on the majority of coins of the Western Turkic Khaganate in Sogdia. This has already been mentioned by other researchers (Babayarov, 2010: 397). The territory of the Turkic khaganates was traditionally subdivided into two parts: eastern and western. The economic and political significance of the aristocratic clans that formed the dual marital union and their influence on khaganate affairs was buttressed by the fact that the eastern part was governed by the khagan’s clan of Ashina, while the western part was under the authority of katun’s clan Ashide (Zuev, 2002: 33–35, 85–88).

The canonicity of the scene and its frequent reproduction on coins, statues, rock surfaces, and household utensils is explained by the illustration of the marital union of two aristocratic clans, whose members might have been perceived as personifications of Tengri and Umay, rather than as simple portraits of a ruler and his wife. Supposedly, even if the three-horned headdress was not an exclusive element of a katun’s (kagan’s wife’s) costume, it reflected the high social status of its owner. This may also be the reason for the scarcity of statues with images of a three-horned headdress.

A large number of facial stelae have been recorded in the Altai. However, the Apshiyakta stelae bearing images of male and female faces on a single facet are unique. No parallels to them have been known either in the Altai, or elsewhere in the territory of distribution of Ancient Turkic statuary monuments that includes Mongolia, Tuva, Semirechye, and Eastern Turkestan. By their extraordinary features, the Apshiyakta stelae can be listed among such single early Ancient Turkic monuments as the Kudyrge boulder (Gavrilova, 1965: Pl. VI) in the Russian Altai, the statue from Khar-Yamaatyn-gol (Kubarev, 2015: Fig. 1, 2) in the Mongolian Altai, and the Kogaly sculpture (see Fig. 8, 5 ) in the Chu-Ili interfluve in Kazakhstan.

The Apshiyakta anthropomorphic stelae and the above-mentioned monuments belong to a single cultural-chronological range of artifacts showing several genre scenes, in which a woman in a three-horned headdress is one of the main characters. Such scenes have been recorded in the Bichiktu-Bom graffiti (Fig. 8, 1, 4), the Kudyrge boulder (Fig. 8, 3) in the Altai, in the horn object from Suttuu-Bulak (Fig. 8, 2) in Kyrgyzstan, and in petroglyphs of the Kogaly locality in Kazakhstan (Rogozhinsky, Solodeynikov, 2012: Fig. 8). Interestingly, the majority of genre scenes have been found in the Altai, while statues with female facial images and three-horned headdresses have been discovered here for the first time, unlike the Semirechye, where quite a number of such monuments has been known (Fig. 5).

It can be assumed that the Apshiyakta sculptures manifest the same idea that is embodied in the genre scenes in yurts––coupled images of the husband (warrior, or batyr ) and his wife ( katun ). The same idea is implemented in the placement of a male and a female sculpture near one enclosure (Altai) or near individual adjoining enclosures (Tian Shan).

Dating the Apshiyakta statues

The Apshiyakta funerary structures represent a single complex, constructed during a single chronological period. This assertion is supported by the following: the enclosures are adjoining, have similar dimensions and construction features, and are accompanied by statues bearing male and female facial images executed in a single artistic manner—possibly by a single artisan. The complex likely belongs to the early Ancient Turkic Period, i.e. to the 6th–7th century. As is known, the adjoining enclosures are attributable to the earliest Ancient Turkic funerary structures. At that period, funerary sites, like the iconography of statues created by the Ancient Turks of the Altai, had not yet gained their final classical look. They might have been face stelae, realistic three-dimensional sculptures, or anthropomorphic stelae. The Apshiyakta statues should be interpreted in this context. They represent a variant of face-sculptures, with the difference that they bear two facial images. The schematic representation of the faces serves as an additional argument for the early dating of these monuments.

The radiocarbon analysis of a horse’s tooth that was found close to the Apshiyakta stela provided the date of 1486 ± 52 BP. Calibration calendar intervals by 1σ have been estimated as 540–639 AD, by 2σ, 429–495 AD (18 %), 507–521 AD (2 %), and 526–652 AD (79 %). It may therefore be asserted that the funeral structures and statues were created 526–652 AD. This is well correlated with the date of the Kudyrge burial ground (late 6th–7th century), and possibly of the majority of genre scenes and sculptures bearing images of threehorned headdresses. This date also supports our assertion that facial stelae and adjoining enclosures of the Kudyrge type belong the early period in the history of the Old Turks. The abovementioned Sogdian coins (Shagalov, Kuznetsov, 2006: 75, 79) provide one more argument for the attribution of the images of women in three-horned headdresses, and the scenes portraying a ruler and his wife, to the period of the 6th–7th century.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the following inferences can be made.

-

1. Ancient Turkic female statues are to be found in Central Asia, though currently only few of them have been discovered. A rather large number of sculptures of women bearing three-horned headdresses have been recorded in Semirechye. It is likely that a significant proportion of the Ancient Turkic facial stelae that lack mustache, beard, and weapons, and are found in Southern Siberia, Eastern and Western Central Asia, depict women. The quantity of such stelae reaches one third of the total number of Ancient Turkic sculptures known so far.

-

2. Female statues of the Ancient Turkic tradition should not be conflated with the Kimek-Kipchak images, as some researchers do. These statues are distinct in their style, in depicted realities, in their placement (at the funeral enclosures versus inside the so-called sanctuaries), and also, probably, in their semantics and purpose. The Ancient Turkic female sculptures always show or imply clothing. Female breasts were never depicted in them, unlike the Kimek-Kipchak statues.

-

3. The Ancient Turkic sculptures with representations of three-horned headdresses, like the characters wearing such headgear engraved on stone, bone, etc., portray noble women, but not shamans/shamanesses; and even more emphatically, not the goddess Umay or Mother of God. This inference is supported by all the mentioned facts: placement of statues at the funerary enclosures, the family character of some of these monuments, representations of the Turkic ruler and his wife on the Sogdian coins, canonical representation of a man and a woman in a yurt, etc.

-

4. Statues representing women in three-horned headdresses have been recorded mostly in Semirechye, and only two of them were found in Apshiyakta, in Altai. However, the images of noble women of the Ancient Turkic period were distributed over a considerably larger area, from Khakassia to Sogdia, Central Asia. Nevertheless, the majority of such engraved images have been found in Altai and in Semirechye.

-

5. The Apshiyakta statues belong to the single cultural-chronological range of sculptures, rock engravings, and grave goods and coins, which have been mentioned as parallels. They are dated to the early Ancient Turkic period of the 6th–7th century.

-

6. Apparently, the canonical scene showing a ruler and his wife sitting in a yurt represents an illustration of the marital union of the two Ancient Turkic aristocratic families of Ashina and Ashide. This union was mentioned

in Chinese and autochthonous written records. The scene can be regarded as a type of encoded information on the structure of the Ancient Turkic state, and also as a symbolic representation of the divine couple of Tengri and Umay. This is the reason for the broad distribution of this scene, which was reproduced on rocks, statues, household utensils, and on coins of Western Turkic Khaganate. Its popularity suggests that it was very meaningful and symbolic for Ancient Turks.

This is probably the reason why statues representing women in three-horned headdresses were dispersed mostly in Semirechye, the western part of the Turkic khaganates headed by the Ashide aristocratic family. The images might have represented women from this family. Also, the ruling couple probably personified the male and female principles and the material incarnation of the two supreme deities, Tengri and Umay. This is evidenced by the epithets that were used to describe khagan and his wife ( katun/khatun ) in runic texts: khagan is “Sky/Tengri alike, raised by Heaven (or born by Heaven)”; “mother-katun, Umay alike”. The female principle in this scene was stressed by the image of pregnant ruler on the coins of Western Turkic Khaganate from Sogdia and Tokharistan. The goddess Umay was known as a patroness of children and pregnant women. However, we cannot as yet speak about the established iconography of the Tengri and Umay deities among the Ancient Turks.