On early medieval contacts of the Urals and Western Siberia with Central Asia: the evidence of ceramics

Автор: Matveeva N.P.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146231

IDR: 145146231

Текст статьи On early medieval contacts of the Urals and Western Siberia with Central Asia: the evidence of ceramics

Discussions about the area, the time of development of the Magyar ethnos, and the exodus of the Magyars from the territory of their ancestral home usually refer to the early medieval materials from the Urals and Western Siberia* (Ivanov V.A., 1999, 2015, 2018b; Belavin, Ivanov, Krylasova, 2009; Türk, 2012; and others), which we agree with (Matveeva N.P., 2018). Following A.V. Komar, who suggests looking for the Magyar nomad territories in the Southern Uralian-Kazakhstan region, on the basis of the combination of Sogdian features of metal art, Cis-

Urals belt decoration sets, and the Srostki elements of outfit and horse harness (2018: 251, 254), I would draw your attention to the Western Siberian and Central Asian contacts of the sought nomads recorded on the basis of ceramic studies.

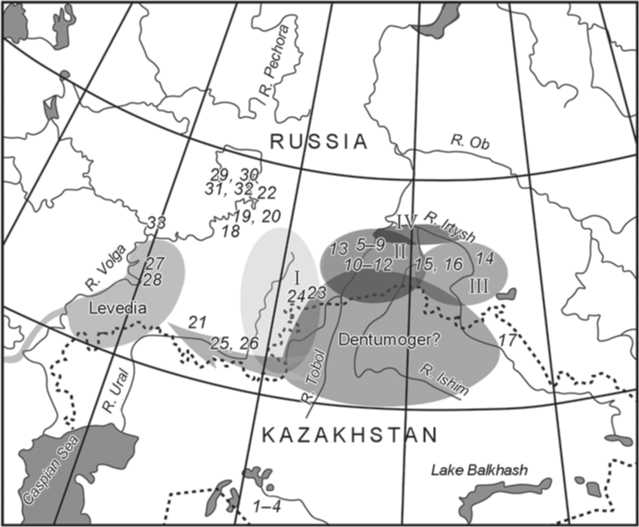

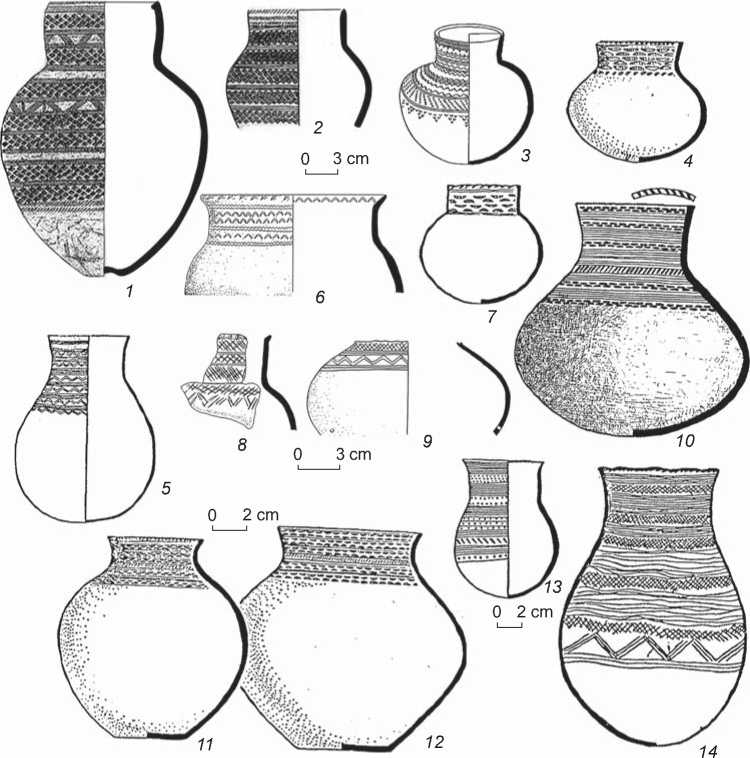

It has been established that in the Early Middle Ages in the forest-steppe areas, pottery-making was developed on the basis of indigenous technologies and innovations brought by migrants (Botalov, 1988: 130; Vasilieva, 1993: 46; Ostanina, 1997: 181; Belavin, Ivanov, Krylasova, 2009: 151; and others). On both sides of the Ural Range, we observe significant differences in the forms and methods of pottery construction in ceramic assemblages of various archaeological cultures (Fig. 1), and sometimes also alien recipes for paste, which suggests imitation of imported samples and direct distribution of imported

Fig. 1. Typical forms of ceramics from the medieval sites of the Cis- and TransUrals.

1–5 – from kurgans “with mustaches” (after (Botalov, 2009: Fig. 9)): 1 – Kara-Bie, kurgan 1, 2 – Novoaktyubinsk I, 3 , 4 – Kyzyltas II, 5 – Gorodishche IX; 6 , 7 , 14 – Potchevash: 6 , 7 – Okunevo-3 (after (Arkheologiya Omska, 2016: 272)), 14 – Kolovskoye, photo by A.S. Zelenkov; 8 , 13 , 15 – Bakalskaya, Ustyug-1; 9 , 10 , 16 , 17 – Kara-Yakupovo: 9 , 10 – Graultry (after (Botalov, 2000: Color pl.)), 16 , 17 – Bekeshevo kurgans (after (Fodor, 2015: 108)); 11 , 12 – Kushnarenkovo, Ufa, Sytyshtamak kurgan (after (Fodor, 2015: 105)); 18 – Bakhmutino, Birsk; 19 – Chiyalek, Bolshie Tigany .

Sources

Comparisons of pottery from the forest-steppe of the Trans-Urals, Cis-Urals, and the adjacent regions of the Kazakhstan steppes (Fig. 2) were carried out on the basis of publications on the Kushnarenkovo sites (Botalov, 2009; Mazhitov, 1977; Mazhitov et al., 2011; Sultanova, 2000; Zelenkov, 2015, 2019). The authors indicate that Kushnarenkovo ceramics have been found at more than 120 sites in Bashkiria, Udmurtia, and Tataria. We have examined various collections of Kushnarenkovo, Kara-Yakupovo and Turbasly antiques from the excavations by N.A. Mazhitov, G.I. Matveeva, and other researchers, which are deposited in the Bashkortostan National Museum (Birsk fortified settlement and cemetery, settlements of Taptykovo-2–4, -6, -7, and -9, Kazanlar, Kara-Yakupovo, Stary Kalman, and Novye Turbasly; and cemetery of Novye Turbasly, burial mounds of Lagerevo and Ordzhonikidze, Kadyrovo-1); Nevolino

Fig. 2. Map showing location of the mentioned sites.

1 – 4 – Altynasar-4, Kosasar-2, Bedaikasar-2, Tompakasar; 5–9 – Ustyug-1, Kozlov Mys-2, Revda-5, Pereyminsky, Kolovskoye; 10–13 – Karasye-9, Ust-Tersyuk, Ust-Utyak-1, Bolshoye Bakalskoye; 14 – Ust-Tara-7; 15 , 16 – Loginovo, Likhacheva; 17 – Bobrovka; 18 – Birsk; 19 , 20 – Lobach, Verkh-Saya; 21 – Sakmara; 22 – Ufa II; 23 , 24 – Selentash, Kaynsay; 25 , 26 – Turganik, Imangulovo; 27 , 28 – Proletarskoye, Karlinsky; 29 , 30 – Varna, Tolyensky; 31 , 32 – Kuzebaevo, Blagodatskoye; 33 – Bolshie Tigany.

I – IV – areas of distribution of the Kara-Yakupovo (I), Bakalskaya (II), Potchevash (III), and the southern variant of the Karym (IV) cultures.

materials kept at the Archaeology Department of the Udmurt State University (Verkh-Saya and Elkino fortified settlements, and Brody). Comparisons were carried out with the ceramic assemblages of the Bakalskaya culture (fortified settlements of Kolovskoye, Krasnogorskoye, Ust-Tersyuk, Ust-Utyak-1, and Bolshoye Bakalskoye (Matveeva, Berlina, Rafikova, 2008; Botalov et al., 2013; Zelenkov, 2019); and cemeteries of Ustyug-1, Kozlov Mys-2; Revda-5, and Pereyminsky (Matveeva N.P., 2016: 138–153). The Potchevash ceramics have been described by B.A. Konikov (2007) and V.A. Mogilnikov (1987); samples for comparisons were taken from the collections of the Loginovo fortified settlement and Likhacheva cemetery belonging to the Tyumen Regional Museum Association, as well as from Bobrovka cemetery (Arslanova, 1980). The Dzhetyasar culture of the Aral Sea region was examined in the collections by L.M. Levina (Altynasar-4, Bedaikasar-2, Kosasar-2 and -3, and Tompakasar) from Moscow museums. Analysis of the entire materials of the Kushnarenkovo ceramics has not been carried out, because not all the materials have been described yet. We consider this to be the task for the nearest future.

Discussion

It would seem that the red- and black-polished thin-walled (3–4 mm thick) ceramics of the Kushnarenkovo type (see Fig. 1, 11, 12), original in its jug shapes and figured-stamped ornamentation, should correlate with peculiar rites and lifestyle, which was implied in identification of this culture. The technological features of this pottery were analyzed by I.N. Vasilieva (1993: 44–45) and A.S. Zelenkov (2019). The techniques of its manufacture look foreign against the background of the traditions of the neighboring population groups of the Cis-Urals; because in contrast to the coiling technique, the molding was carried out using mold-models, including leather models, patch stamping, with careful smoothing and polishing; sometimes engobing was applied for final leveling of the surface (Vasilieva, 1993: 46). Some techniques show similarity with the Turbasly ceramics (Ibid.: 83); however, the type under consideration is distinguished by the presence of fine graded sand in the paste, and by its thinness.

It was noted that at all the settlements and cemeteries of the Cis-Urals, the Kushnarenkovo ceramics were found together with the Turbasly, Bakhmutino, Nevolino, or Kara-Yakupovo ones, and did not correlate with any type of burial (Mazhitov, 1977: 62, 72; Kazakov, 1981: 133). Since most of the sites have not been fully described, and no summary of the excavation reports has been made, we provide the data from digital and illustrative publications.

Kushnarenkovo ceramics are always few in number, in contrast to other pottery types (Gening, 1972: 266, 268; Kazantseva, Yutina, 1986: 122). Their share in the assemblages is from 1 to 16 % (see Table ), which is determined very approximately, since the material was not distributed by the authors of publications by dwellings or horizons, and the ratios of various types are quite random, depending on the size of the exposed areas and the chronology of the objects. Notably, in the settlements, the Kushnarenkovo vessels are much smaller than the Kara-Yakupovo ones (Ivanov V.A., 1999: 50). General comparison of shapes and sizes led N.A. Mazhitov (1981: 27–28) and T.I. Ostanina (2002: 42) to the conclusion that this was tableware.

Occurrences of the Kushnarenkovo ceramics in the burial and settlement sites of the Trans-Urals and Cis-Urals

|

Site |

Number of vessels / proportion, % |

Source |

Site |

Number of vessels / proportion, % |

Source |

|

Verkh-Saya fortified settlement |

16/0.69 |

(Pastushenko, 2008) |

Novobikkino |

1/? |

(Mazhitov, 1977) |

|

Verkh-Saya cemetery |

1/0.84 |

(Ibid.) |

Bulgar |

1/? |

(Ibid.) |

|

Bartymskoye-1 site |

2/0.18 |

ʺ |

Ufimsky |

1/? |

ʺ |

|

Morozkovskoye-4 site |

1/0.07 |

ʺ |

Murakaevo |

1/? |

ʺ |

|

Antonovskoye fortified settlement |

1/1.41 |

ʺ |

Sterlitamak |

2/? |

ʺ |

|

Khalilovo |

1/? |

(Mazhitov, 1977) |

Karanayevo |

3/? |

ʺ |

|

Manyak |

21/? |

(Ibid.) |

Khusainovo |

3/? |

ʺ |

|

Krasnogorsky |

1/? |

ʺ |

Ishimbay |

1/? |

ʺ |

|

Kushnarenkovo |

2/8.69 |

(Vasyutkin, 1968) |

Starokolmashevo fortified settlement |

56/? |

ʺ |

|

Bakhmutino |

2/? |

(Mazhitov, 1977) |

Birsk |

18/15.4 |

(Sultanova 2000) |

|

Shareyevo |

2/? |

(Ibid.) |

Novye Turbasly site |

18/? |

(Mazhitov, 1977) |

|

Staroyanzigitovo |

2/? |

ʺ |

Birsk fortified settlement |

10/? |

(Ibid.) |

|

Bekeshevo |

10/? |

ʺ |

Romanovskoye-2 site |

9/? |

ʺ |

|

Syntashevo |

2/? |

ʺ |

Turbasly fortified settlement |

4/? |

ʺ |

|

Lagerevo |

16/? |

ʺ |

Ufa II |

100/? |

(Mazhitov et al., 2011) |

|

Novye Turbasly cemetery |

1/? |

ʺ |

Ust-Utyak-1 |

37/12.8 |

(Botalov et al., 2013) |

|

Kolovskoye fortified settlement |

40/7.47 |

(Matveeva, Berlina, Rafikova, 2008) |

Kuzebaevo fortified settlement |

201/16.19 |

(Ostanina, 2002) |

|

Papskoye fortified settlement |

7/10.4 |

(Matveeva et al., 2020) |

Bolshoye Bakalskoye fortified settlement |

21/11.1 |

(Botalov et al., 2013) |

However, their colleagues did not support them, carried away by the ethnic interpretations of the types. Today, Kushnarenkovo ceramics have also been found in the steppe kurgans “with mustaches” (Selentash, Kaynsay, Turganik, Imangulovo) (Grudochko, 2018: Fig. 7; Kraeva, Matyushko, 2018: Fig. 11, 15), and at the seasonal sites in the Volga region (Proletarskoye fortified settlement, Karlinsky site) (Stashenkov, 2018: 258–259). The difference between the pastes of these vessels, including the presence of crushed shells in some of them (Kraeva, Matyushko, 2018: 187), suggests the transformation of the original recipes of paste under different conditions and in a different environment. The emergence of Kushnarenkovo ceramics reflects either the development of local specialized pottery production for high-status consumption, or active trade.

In one of his early communications, E.P. Kazakov noted that burials with Kushnarenkovo ceramics “stand out for their richness of beautifully made items of gold and silver, as well as for quite perfect iron tools and weapons” (1981: 115). Initially, researchers saw the differences in the existence time and orientation of the Kushnarenkovo and Kara-Yakupovo burials, which were classified by vessels of the corresponding type in the graves (Ivanov V.A., 1999: 55, 57; Botalov, 2000: 332); however, owing to the small number of samples, this conclusion turned out to be statistically unreliable. The opinion of V.A. Ivanov on the earlier date of most burials with the Kushnarenkovo ceramics, as compared to the burials with the Kara-Yakupovo pottery (2018a: 97), contradicts the data of A.G. Ivanov, according to which vessels of both types are represented in contemporaneous sites of the 6th to 7th centuries and exist until the 8th to 10th centuries, undergoing gradual transformations (2008: 149–150). Seeing no grounds for the spatial and chronological division of the Kushnarenkovo and Kara-Yakupovo sites, a number of researchers (Botalov et al., 2008: 22–27; Grudochko, Botalov, 2013; Ivanov V.A., 2015: 201, 209) began to use the term “Kushnarenkovo-Kara-Yakupovo culture”, and divided or united the sites

Fig. 3. The Bakalskaya vessels ( 1–6 ) and Dzhetyasar parallels to the borrowed pottery forms ( 7–10 ) from the cemeteries of Altynasar-4 ( 1–7 , 9 , 10 ) and Kosasar-3 ( 8 ).

3 cm

3 cm

3 cm

0 3 cm

0 3 cm

0 3 cm

0 3 cm

4 I_______I

Fig. 4. Vessels of the Bakalskaya forms from the cemeteries of Kosasar-2 ( 1–9 ) and Bedaikasar-2 ( 10 ).

according to the existing situation. By the way, Vasilieva showed the difference in the pastes, reflecting the peculiarities of substrate pottery skills among the groups of producers of these types of ceramics: iron ductile clay tempered with manure and grog in the Kushnarenkovo tradition, iron oversanded clay, sometimes with mica, in the Kara-Yakupovo (1993: 44–45).

In Western Siberia, the Kushnarenkovo ceramics are found together with Bakalskaya pottery, in the early medieval sites dating to the 4th to 7th centuries. The study of the specifics of pottery-making based on the materials of the cemeteries of Kozlov Mys-2 and Ustyug-1 showed that the Trans-Urals population borrowed the forms of cups, mugs, jugs with handles, and cauldrons from the southern regions—the Aral Sea region and Semirechye: manufacture of imitation vessels, as well as the use of imported ware with original pastes; for example, tempered with burnt bone (Matveeva, Kobeleva, 2013).

During examination of the Dzhetyasar ceramics (Fig. 3, 4)*, we have discovered solitary specimens of the Bakalskaya culture from several sites in the lower Syr-Darya River. For instance, in kurgans 245, 275, 294 and others at Altynasar-4, pottery of the Western Siberian appearance was found. This pottery differs from the flat-bottomed and thick-walled Dzhetyasar pots in its rounded bottoms, thin walls, presence of sand and grog in the paste, and short necks with straight cut or notched rim. The collections from the cemeteries of Kosasar-2 and Bedaikasar-2 contained similar ware: round-bottomed pots with short necks, hand-made and fire-baked mugs; some of the specimens show admixture of burnt bone in the paste and are light in weight (Fig. 4, 6, 7), similarly to some vessels from the Tobol region (Ibid.: 72). In all the collections we have examined, such dishes are in the minority (maximum one tenth) and are dissimilar to the main array, consisting of thick-walled flat-bottomed pots, cauldrons, bowls, and jugs of forge-baking. In addition, in the Bakalskaya assemblages, there are some rare forms, the origin of which had not previously been explained; namely, the high-necked red-clay jugs with grooved necks, including those with zoomorphic handles, polished bowls, and mugs with handles; these forms find complete parallels in the Aral Sea region (see Fig. 3, 7–10; 5, 6). In general, the Trans-Urals pottery from the sites dating to the 4th–6th centuries imitates the forms of the Dzhetyasar I period, the earliest date of which was determined by L.M. Levina to be the 4th century AD (1971: Fig. 15, 17).

Comparison of the local Bakalskaya pottery (consisting of round-bottomed pots, cans, cauldrons, pans, cups and bowls (Fig. 6, 12–19 )), with imported ware (Fig. 6, 1–7 ) and imitations (Fig. 6, 8–11 ) has shown that the imported products are represented by flat-bottomed jugs and mugs used for ceremonial serving of drinks, probably kumis and milk vodka. Judging by the results of the analysis of charred deposits on the vessels from the burials, the pots and bowls contained soups and broths, and the jars water (Matveeva N.P., 2016: 143). This means that the ceremonial ware reflects some kind of ritual innovation or high-status consumption. Thus, ceramic materials testify to active trade relations in the meridian direction— possibly accompanied by marital links, since the Bakalskaya vessels were found in the Dzhetyasar burials.

Statistical analysis of the Trans-Urals burial sites showed that the graves with Kushnarenkovo vessels are not grouped into a separate cluster, but are distributed among the Bakalskaya and Potchevash burials (Zelenkov, 2017).

Let us consider the forms and decorations of the Kushnarenkovo ceramics. Ceramic materials from the Ufa II fortified settlement (ca 60 spec.) (Zelenkov, 2015: 1960) show that the predominant forms of Kushnarenkovo ware are medium-high and high round-bottomed pots. Such vessels also dominate in other assemblages (Fig. 7, 9–12 ), while spherical vessels with low necks form a

Fig. 5. Specimens of Dzhetyasar tableware, imitations of which were noted in the Bakalskaya assemblages of Ustyug-1 and Revda-5 cemeteries.

1–5 – Kosasar-2; 6 – Altynasar-4.

separate group (Fig. 7, 4 , 7 ), with a specific decoration made with figured stamps (triangles, rhombuses, brackets, “caterpillars”). The origin of this motif is associated with the southern version of the Karym culture, with migrants from the taiga zone to the Western Siberian foreststeppe (Fig. 7, 1 , 2 ) (Zelenkov, 2015: 198). Burials in the Cis-Urals and Trans-Urals also yielded a significant proportion of high-necked jugs with carved and grooved or with figure-stamped ornaments (Fig. 7, 5 , 10 , 13 ). The narrow-necked elongated vessels have parallels among the churns from Altynasar-4 (see Fig. 3, 7 ). The decoration pattern of incised lines with a multi-row zigzag between them is also characteristic of ceramics from the sites of the 4th–7th centuries at the lower Syr-Darya River (Levina, 1971: Fig. 15, p. 72).

L.S. Kobeleva, having examined the sample from Ufa II under a microscope, concluded that some of the ceramics are replicas of Kushnarenkovo pottery. These ceramics are coarser and thicker-walled, their surfaces were processed with a denticulate tool and were neither completely smoothed nor polished. The imitation vessels were decorated carelessly, with frequent mismatches in the rapport; comb imprints were almost not used; in one case, the comb bracket was replaced by nail

3 cm

rWW

0 2 cm

0 2 cm

2 c

"С © © С <

0 2 cm

Ж*\«\^ 5.V///»//

cm

Fig. 6. Imported ware ( 1–7 , 20 , 21 ), imitations ( 8–11 ) and typical forms ( 12–19 ) from the sites of the Bakalskaya culture.

1 , 2 , 14 , 15 , 18 – Kolovskoye fortified settlement; 3 , 4 , 20 , 21 – Ust-Tersyuk; 5 – Ust-Utyak-1; 6 , 7 – Karasye-9; 8 , 13 – Revda; 9–12 , 16 , 17 – Ustyug-1; 19 – Pereyminsky cemetery.

imprints*. There are specimens with a dense carved pattern, executed with a metal ornamenting tool and a plain stamp. The proportions of necks with sharply everted rims (see Fig. 7, 6, 8) in other Kama pottery are closest to the jug forms of the Dzhetyasar II period, hand-made on swivel stand (Ibid.: 73). Materials from archaeological sites in Udmurtia (Varna, Tolyensky cemeteries, Verkh-Saya, Lobach, Kuzebaevo, Blagodatskoye fortified settlements) give the impression that the Kushnarenkovo patterns were borrowed from that local environment for which the products were intended (see Fig. 7, 6, 8). It was noted that, over time, there was a change in forms that approached the spherical and miter-shaped local standards, and the decoration became more rarefied (Ivanov A.G., 2008: 156, 158), i.e., there was adaptation to consumer preference.

We believe that the abovementioned facts do not provide a good ground for regarding the Kushnarenkovo ceramics as an archaeological culture. Kushnarenkovo pottery was manufactured by artisans who still worked without potter’s wheels, using something like the methods of pot-makers of the Sakmara fortified settlement, in the steppe of the left-bank Volga region. Vasilieva showed that the ceramics from this site do not belong to the Urals cultures; these were made in situ,

Fig. 7. Karym, Potchevash vessels and Kushnarenkovo ceramic forms from the Nevolino and Bakhmutino sites.

1 , 2 – Ust-Tara-7; 3 – Bobrovka cemetery; 4 , 5 , 7 , 10–14 – Birsk cemetery; 6 , 8 – Lobach; 9 – Verkh-Saya.

in the traditions of the Dzhetyasar culture, by some group of the population that moved from the territory of Kazakhstan to the northwest (1993: 86).

Conclusions

The Kushnarenkovo and pseudo-Kushnarenkovo forms of ceramics on both sides of the Urals emerged under the influence of trade and demand for prestigious ware, the decoration of which was borrowed partly from the Karym and Potchevash population of the subtaiga zone of Western Siberia, and partly from the Kama and Aral Sea regions. Whether it was produced in sedentary settlements of the Kazakhstan steppes or in trade factories of the forest-steppe remains to be determined. We should move away from the definition of the Kushnarenkovo antiquities in terms of culture and consider them a type, with the possibility of interpretation as a subculture of some population group. Of course, a comprehensive analysis of all Kushnarenkovo pottery is required, clarifying its chronology and forms, highlighting originals and imitations; these topics are the goals of future studies.

The existence of trade factories and itinerant artisans in the Cis-Urals in the Early Middle Ages is evidenced by coin hoards and precious vessels found in the Sylva River area, in the middle Kama, the Kuzebaevo jeweler’s hoard, and explicitly Central Asian imported products (Goldina E.V., Goldina R.D., 2010: 170, 172–173). There are similar finds in the Trans-Urals: a handle from a Central Asian vessel from the Bolshoye Bakalskoye fortified settlement (Botalov et al., 2008: Fig. 15), Chinese coins and mirrors from the cemeteries of Kip III and Likhacheva (Mogilnikov, 1987: 192), a silver bucket and mugs from the Iset River area, and other evidence of trade with medieval Sogdian settlements of Semirechye on the way from the Aral Sea region to the lower reaches of the Volga (Darkevich, 2010: 44–45, 146). These facts make it possible to consider the forest-steppe as a zone of intense interactions, which still remains insufficiently studied.

In the assemblages of the “Hungarian” toreutics that appeared later in the steppe zone, the Khazar, Byzantine, Sasanian, “Tang”, and Srostki borrowings are noted. According to A. Türk, close Central Asian contacts began east of the Volga in the Early Middle Ages, and the preceding trade determined a set of components of cultural genesis in the 8th to early 9th centuries (2013: 236). Apparently, trade was also actively carried out in the Urals and Western Siberian region by the bearers of the Bakalskaya and Potchevash archaeological cultures.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 19-59-23006) and the Foundation for Russian Language and Culture in Hungary.