On the interpretation of Stelae in the cult complexes of Northern Mesopotamia during the pre-pottery Neolithic

Автор: Kornienko T.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145392

IDR: 145145392 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.4.013-021

Текст статьи On the interpretation of Stelae in the cult complexes of Northern Mesopotamia during the pre-pottery Neolithic

The appearance of permanent architecture was one of the most important innovations during the transition to the Neolithic*, and had an important influence on development of complex symbolic systems. In the limestone-rich central Fertile Crescent region, this was manifested both through the tradition of building living spaces, and houses of worship specially decorated for public meetings. The emergence of spatial symbolism (including architecture and images) in societies shifting to sedentism accompanied new ways of social interaction (Cauvin, 1994; Watkins, 2006, 2009; and others). Many researchers suggest that innovations in ritual practices contributed to cohesion of long-term, sedentary, and expanding communities, helping to regulate relations among individuals and groups that had to solve many newfound problems introduced by sedentary existence.

The purpose of this paper is to take a closer look at symbolism found on stelae, pillars, and pilasters in religious complexes of Northern Mesopotamia during the transition to the Neolithic. So far, more than 600 such objects have been recorded in this region. The majority of these objects are found in Southeastern Turkey; they are less typical of the adjacent areas.

In a previous study, we provided a general overview of monolithic Northern Mesopotamian stelae dating to this period, which often bear zoo- and anthropomorphic reliefs (Kornienko, 2011). This study identified that vertical, T-shaped slabs, pillars, and stelae were generally placed in public buildings, and represented

important markers of sacral space. Most researchers interpret these objects as anthropomorphic, and occasionally zoomorphic vehicles for ancestral spirits— the patron deities worshiped by early Mesopotamian communities. However, stelae installed in sacral zones (and, in many cases, elaborately decorated) could also convey more complicated meanings.

Exploring the significance of symbolic objects used during the transition to the Neolithic is possible through holistic archaeological study, supplemented by scientific data, ethnographic parallels, behavioral data, semiotics, and mythology, as well as study of the long-standing archaic motifs, including those recorded in early written sources from this region.

Analysis of materials

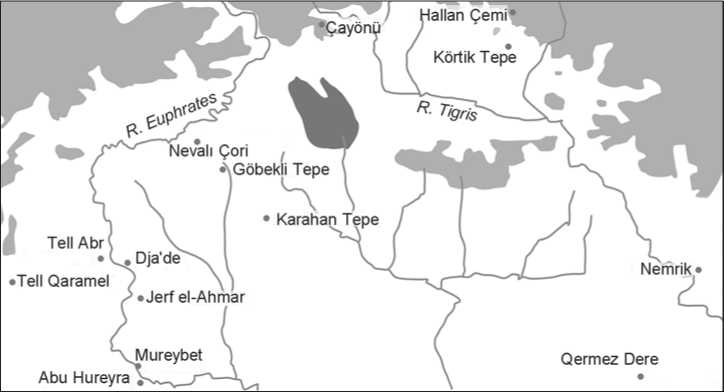

Unlike in the Levant, the domination of male symbols and images over female ones is typical of the Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic materials of Upper Mesopotamia (Fig. 1). Components of this symbolic system include the motif of decapitation, and images of carnivorous, wild, and dangerous animals. These are often interpreted as related to a “cult of the dead” (Schmidt, 2006: 127, 158– 160, 238–240), and may have increased aggression and fear among growing communities (Benz, Bauer, 2013). Meanwhile, themes of female reproduction and fertility, productivity, and abundance appear to have been restricted from the basic concepts of public consciousness of early settlements of Northern Mesopotamia (Hodder, Meskell, 2011: 236). Nevertheless, contextual data from paleoanthropology and archaeology do not support the idea that aggression and violence were widespread in this area in the Neolithic (Erdal Y.S., Erdal O.D., 2012; Kornienko, 2015а: 95–96). Also, it is worth pointing out that burials are not typical elements of public cult complexes.

Stelae, pillars, and columns appear to have been important sacral objects of public cult complexes. In many cases, those objects were decorated with relief or sculptural anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images, which sometimes show complex compositions with many characters. Among these, not only carnivorous animals, but also waterfowl, reptiles, especially snakes (whose image has been regarded ambivalently in some cultures), appear to have been rather popular. Across archaeology, ethnography, and folklore, the image of snake in archaic cultures has been linked to water and earth, to a female generative force, to fertility, but also to hearth, fire, male procreation, family welfare, and childbearing, i.e. procreation (Ivanov, 1991; Ivanova, 2009; Ber-Glinka, 2015, 2016).

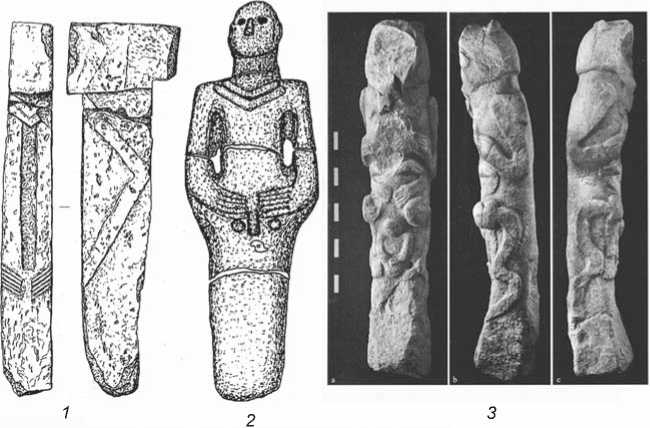

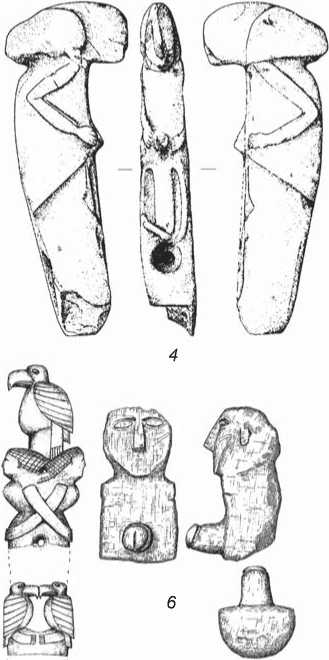

A particular style of T-shaped “Nevalı Çori”-type stelae were discovered at several sites in the Urfa Province, in Southeastern Turkey. These were first encountered in public cult structures, and based on relief images of anatomically correct arms with five-finger hands, bent at the elbows and folded across the belly, appear to have been anthropomorphic (Hauptmann, 1993: 50–52) (Fig. 2, 1 ). Until recently, the gender of these anthropomorphic figures was unclear. However, in other archaeological contexts, sculptural representations comparable with the Nevalı Çori stelae in style, size, material, and composition can be reliably assessed as male (Fig. 2, 2 ). Sometimes, a phallic motif, located in the anatomically correct location, is rendered in the form of a loincloth made of animal skins and having a corresponding shape (Dietrich et al., 2012: Fig. 7, 8) (Fig. 3, 1 ), or with the use of snake images (Fig. 3, 2 ).

The next group of stelae, which show stacked representations of figures, was initially designated

Fig. 1. Locations of key Late Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic sites in Northern Mesopotamia.

Fig. 2. Stelae/pillars and sculptures during the transition to the Neolithic in Southeastern Turkey.

1 – stela from Building III of Nevalı Çori, 2.4 m high (after (Hauptmann, 2000: Abb. 7)); 2 - statue from the Early Neolithic layers at the old center of a modern city of §anliurfa, 1.90 m high (after (Çelik, 2000: Fig. 2)); 3 – stela from level II of sector L9–46 of Göbekli Tepe, 1.92 m high (after (Köksal-Schmidt, Schmidt, 2010: Fig. 1)); 4 – stela from the Adıyaman Province, 80 cm high (after (Verhoeven, 2001: Fig. 1)); 5 – “totem pillar” from Building II of Nevalı Çori, reconstructed from several fragments, over 1 m high (after (Schmidt, 2006: Abb. 16)); 6 – ithyphallic protoma from Göbekli Tepe, 40.5 cm high (after (Ibid.: Abb. 28)).

as “totem columns”—a reference to similar objects made by American Indians. One such object, made of limestone, was made of creatures with human faces and elements of bird bodies. This stela was found in cult Building II (PPNB) of Nevalı Çori (see Fig. 2, 5 ) (Schmidt, 2006: 77–79). Another stela (Early PPNB) from sector L9–46 of Göbekli Tepe shows similar traits (see Fig. 2, 3 ). Three (or, possibly, four) figures placed on top of each other can be recognized in its images. Based on the preserved portion (ears and eyes), the head of the upper figure (the face of which was destroyed in ancient times), appears to have been the head of a carnivore (bear, lion, or leopard?). Below, on its sides, is found a motif known from the Nevali Çori stelae and comparable sculptures of anthropomorphs (see Fig. 2, 2 )—with arms/paws with five-finger hands, bent at the elbows and folded across the belly (see Fig. 2, 1 ). The head of the next figure, also with a chipped-off face, can be found between these. Site excavators note that the motif of a wild beast, holding a human head, is found in several sculptures from Nevalı Çori and Göbekli Tepe (Köksal-Schmidt, Schmidt, 2010: 74). At the same time, comparative-typological analysis of stelae and sculptures from Northern

Mesopotamia during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period indicates that belly projection compositions such as this could have simultaneously designated the phallus of the upper creature (Kornienko, 2011: 85). Below the second figure are the head and arms of the third one, now shown from the front, with the arms also bent at the elbows. The arms of the third figure are folded across its belly, and a projection can be seen under them. Under this projection, the upper part of the stela is split off. Ç. Köksal-Schmidt and K. Schmidt suggest that this figure was engaged in childbirth, although it could alternatively have depicted a phallus (Köksal-Schmidt, Schmidt, 2010: 74). Below the arms of two upper figures are large snakes depicted in relief on the column sides. These snakes could have formed legs/ hind paws of a larger creature. At the same time, images of snakes found in the relevant anatomical zone (cf. Fig. 3, 2 ) may reference fertility. From the front, we can see a multifaceted composition, where each figure located below is smaller than the previous one, and projects from its abdomen or phallus.

An incidental find in the Turkish province of Adıyaman (northwest of Göbekli Tepe) dated to the PPNB (Hauptmann, 2000) shows similar traits. This object also

Fig. 3. Pillars and a sculpture from Göbekli Tepe.

1 – one of two central pillars in Building D, ca 5.5 m high (after (Dietrich et al., 2012: Fig. 8)); 2 – pillar 57 (after (Dietrich et al., 2014: Fig. 7)); 3 – animal sculpture (after (Hauptmann, 1999: Fig. 26)), 68 cm long (after (Schmidt, 2006: Abb. 42)); 4 – pillar 43 (after (Schmidt, 2007: Abb. 109)).

contains a sequence of figures (see Fig. 2, 4), wherein the face of the lower human figure projects from the abdomen or pelvis of the upper one. The head of this figure can be interpreted as belonging to some creature, possibly an anthropomorph, but more likely belonged to some animal—for example, a lizard/varan, a reptile inhabiting this terrain and repeatedly represented in images at Göbekli Tepe. The lower figure (whose body and arms can be interpreted as a phallus of the upper one, when viewed frontally) has a depression below the arms folded across its abdomen. Recognizing this feature, scholars have suggested that the figure is hermaphroditic, or that the depression was for the insertion of a sculptural phallus (Verhoeven, 2001; Hodder, Meskell, 2011: 238). The last hypothesis is plausible, since stone representations of phalli are known from Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic materials across Northern Mesopotamia (Schmidt, 2006: 158–160). Repeated rendering of the motif of genitals on the stela, along with a combination of male and female ones (with male predominating) would have enhanced the magical meaning of this object as a symbol of procreation and fertility.

It is quite probable that themes and images repeated on Early Neolithic stelae of Northern Mesopotamia visualized the ideas conveyed later in biblical, Old Testament expressions referencing ancestry and genealogy, such as: “A begat B (…), B begat C (…), C begat D (…)”, etc., or phrases like “springing from/coming out from the loins”*. The visual theme of succession in these sculptures appears to dramatically illustrate the idea of (predominantly patrilineal) kinship with continuity across generations (Kornienko, 2015a: 100–103).

A typical feature of the Early Neolithic images of Northern Mesopotamia is the presence of a large number of animal forms, including bulls, birds, reptiles, arachnids, and carnivorous animals. Across the symbolic depictions found in different archaic societies, animals are often one of manifestations of the mythological code (along with plants, food, colors, and other themes) used to express messages, specifically through mythological discourse (Toporov, 1991).

In symbolic objects of Upper Mesopotamia during the transition to the Neolithic, a mix of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic images is often observed. Often, it is rather difficult to unambiguously interpret the tops of stelae as human heads, including those of the “Nevalı Çori type”. In a number of cases, these heads appear largely zoomorphic. This scenario can be observed in two of the stelae described above (see Fig. 2, 3 , 4 ), and in central pillars from Building ЕА 100 in Jerf el-Ahmar (Stordeur et al., 2001: Fig. 11)). Zoomorphic heads of the upper figures, with human heads projecting from their abdomen or phalli on “totem pillars”, or combined images of phallus with animals seen in other stelae (see Fig. 3, 1 , 2 ), may convey the idea of kinship between communities that produced each pillar, and the animals themselves.

In Early Neolithic materials of Northern Mesopotamia, totemic, animistic religious elements are also evident in the ritual deposits of human skulls and remains of wild aurochs ( Bos primigenius ) inhumed during construction

*Genesis 15:4, 35:11, 46:26, 49:10; Exodus 1:5; Judges 8:30; 2 Kings 7:12, 16:11; 3 Kings 8:19; 2 Chronicles 6:9, 32:21; Isaiah 48:19. Such phrasing is also encountered several times in the New Testament (The Acts 2:30; To the Hebrews 7:5, 10), for example, in the Greek language, where it pertains to obvious Hebraisms. The word “loins” in the synodal translation can refer to several Hebrew words, but in all cases the same verb yāṣāh (‘come out of, originate’) is present or implied. I am profoundly grateful to L.V. Manevich, a scholar and Hebraist, for detailed consultations on these issues.

of special public structures at Jerf el-Ahmar*, Tell Qaramel (Mazurowski, Biatowarczuk, Januszek, 2012: 52–56, pl. 14; Gawrońska, Grabarek, Kanjou, 2012), and Tell Abr-3 (Yartah, 2016: 31, 34–40, 42, fig. 14, 4 ; 16; 17, 5 ). Ritual buildings at Hallan Çemi were ornamented with horns and skulls of animals (usually but not exclusively the aurochs) (Rosenberg, Redding, 2000: 45–46, 57), Çayönü (Çambel, 1985: 187), and Tell Abr-3 (Yartah, 2016: 38). Finally, accumulations of animal bones were found in public areas where feasts took place at Hallan Çemi (Rosenberg, 1999: 26, 28, fig. 16; Rosenberg, Redding, 2000: 58), Çayönü (Çambel, 1985: 187), Tell Abr-3 (Yartah, 2016: 34), and Göbekli Tepe (Dietrich et al., 2012: 690). Animals were also interred within human graves in the Çayönü Skull Building (Le Mort et al., 2000: 40) and at Körtik Tepe. These burials were also characterized by rich grave goods and a diverse range of funerary rites (Erdal, 2015: 6). Human and animal burials were densely concentrated with or near the so-called “sanctuary” of Tell Qaramel (Mazurowski, Biatowarczuk, Januszek, 2012: 52; Gawrońska, Grabarek, Kanjou, 2012). In Göbekli Tepe, researchers discovered the tail vertebrae of a fox near the foot of one of the central pillars of Building D, right under a loincloth made of animal skin, depicted in relief**. In this relief, a tail image occupies the central position, and is combined with the phallus image of the figure depicted (see Fig. 3, 1 ). The fox tail remains may be linked with the loincloths of figures seen on the central stelae of Building D. Researchers assume people could apply costumes in PPN rituals (Notroff, 2016: 7).

It is important to note that the skillful carvings seen on stelae and pilasters at the ritual/cult complexes of Northern Mesopotamia during the transition to the Neolithic closely echo the signs and symbols drawn from other lines of evidence to understand early religion in the Near East. A comprehensive and contextual consideration of these sources alongside the stelae carvings brings a better opportunity for understanding the meaning encrypted in them.

The motif of a head separated from the body appears to have been important within the Mesopotamian symbolic lexicon. This motif appeared in the funerary practices, as seen in isolated burials of skulls, as well as in imagery. Globally, many prehistoric cultures practiced a kind of “head cult”, wherein heads were thought to concentrate human life and strength (Mednikova, 2004).

As the whole is often represented by its part in symbolism across cultures, heads are often used to designate the human whole. Postmortem treatments of the skull/ head (Alekshin, 1994), such as clearing the bones from soft tissues or covering them with clay, ocher, or other additives (Erdal, 2015), or other ritual actions using human remains, were typical of Levant and Northern Mesopotamia during the transition to the Neolithic, and were associated with rites of creation or production (Kornienko, 2015b).

The phallic motif appears to have been another crucial element in the symbolic system of Northern Mesopotamia during the transition to the Neolithic. Monolithic stelae, including T-shaped ones, are likely themselves a symbolic expression of the phallus. Moreover, the “totem pillars” combine phalli of the upper figures (from whose loins, the lower figures originate) with the heads of the lower characters. The repetition of this image (merging the head, phallus, human, and animal images) shows links with

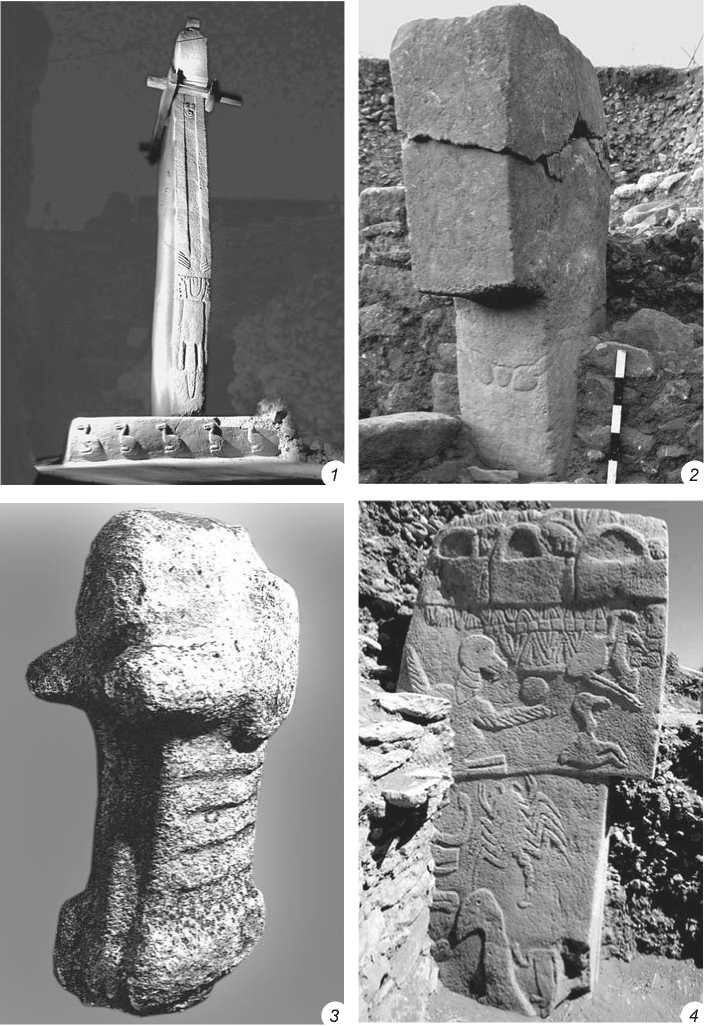

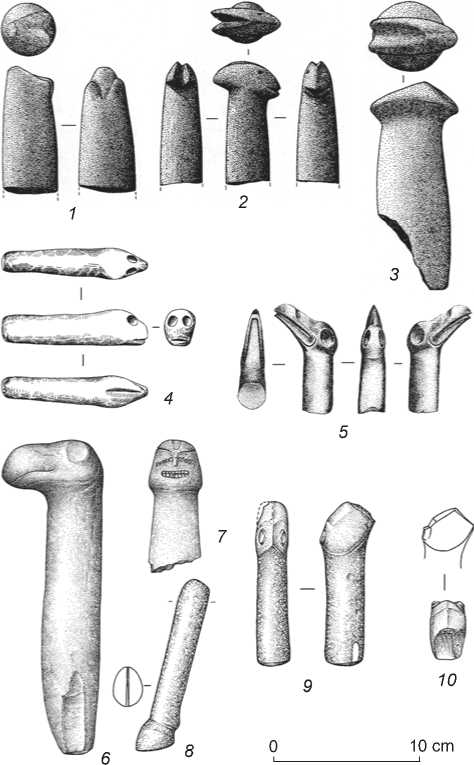

Fig. 4. Stone pestles from Hallan Çemi ( 1–3 ) (after (Rosenberg, 1999: Fig. 4)), and sculptures from Nemrik-9 ( 4–10 ) (after (Kozlowski, 1997: Fig. 1-3)).

totemic ideas of procreation and links between ancestors and generational succession, as well as a connection between life and death.

Discussion

Several rather strange sculptures of a man (see Fig. 2, 6 ) and an animal (see Fig. 3, 3 ) with erect penises show the head and phallus as key symbols for indicating human and animal figures in the Mesopotamian symbolic system. In these sculptures, the head and phallus of these anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures are particularly emphasized (cf.: (Stordeur, Lebreton, 2008: Fig. 1)).

Symbolic objects that combine images of head, phallus, and totem include sculptures from Nemrik-9 (Kozlowski, 1997), and sculptural pestles from Hallan Çemi (Fig. 4). The latter may have been used along with carefully crafted, and often decorated, stone bowls (Rosenberg, 1999: 28, fig. 3; Rosenberg, Redding, 2000). The famous subject of pillar 43 from Building D of Göbekli Tepe also manifests this symbolic pattern. This pillar is covered with relief patterns of snakes, birds, scorpions, other animals, along with abstract symbols. In the lower right part of the stela, a slightly damaged representation of a beheaded man with erect phallus has been revealed (see Fig. 3, 4 ). K. Schmidt reasons that the absence of the head and the presence of erect penis suggest a violent death of the depicted man (as erection sometimes accompanies death) (2007: 259–264, fig. 109). Probably, this scene depicts extraordinary (real or mythic?) sacrifice (Kornienko, 2015b: 46–48) channeling early Mesopotamian concepts of the world order. The absence of the head and the presence of erect phallus on this figure demonstrate a connection between life and death. As with other archaeological data illustrative of early religious practices in the region (including the installation of stelae, organization of collective feasts, complex rituals involving heads/skulls and bones of humans/animals, the ritual use of pestles with bowls, the use of tools for straightening shafts and arrows, and others), life appears to have been reenacted in symbolism, unlike our current rational understanding of things.

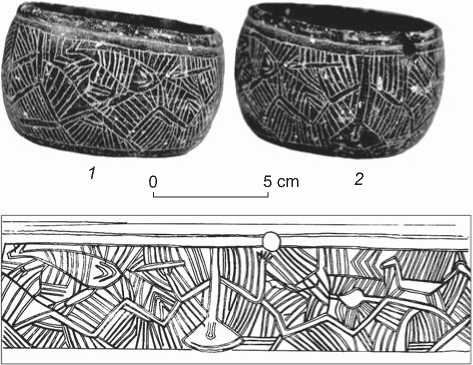

A hunting scene (Fig. 5) engraved on a stone bowl from Building M1b at Tell Abr-3, wherein the hunter’s head is absent and a phallus and the spear (in a raised hand) aimed at an animal are distinctly shown (Yartah, 2016: 31–33, fig. 5, 3 ), suggests a symbolic interchangeability of phallus and head. This image also reinforces a close relationship between human and animal, as well as life and death in this symbolic system.

When considering ethnographic and historical examples across time and space C. Sütterlin and I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt draw attention to the common function of stelae in demarcating and protecting collective territory.

In particular, these authors suggest that the aggressive phalli of anthropomorphic stelae and figures located at boundaries, such as in fields and gardens, indicate a protective role. The phallic symbolism seen in early Mesopotamian stelae, their association with fertility deities, their regular occurrence in the immediate vicinity of burials support the interpretation that phallic demonstration serves a function of guarding (protection) (Sütterlin, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 2013).

Previous research has indicated a tradition of decorating the walls of Sumerian temples and cities with pilasters, and installation of stelae along the symbolic borders of some temples, recorded since the Ubaid period. These architectural elements had a symbolic function similar to that of protective amulets (Kornienko, 2006: 169– 171; 2011: 92). Similarly, Babylonian boundary marks ( kudurru ) are noteworthy, consisted of vertical stones with inscriptions and protective symbols of deities. The kudurru concept was an important idea for Babylonians, and this word was sometimes even included in the name of a ruler. There also exists a genre of kudurru texts. The word itself has several meanings: 1) boundary mark, border, territory; 2) a basket for carrying earth, bricks, or a wooden container; 3) son. There are also alternate translations of the term (for details see (The Assyrian Dictionary…, 1971: 495–497)). For example, the name “Nebuchadrezzar” (Nabû-kudurri-uṣur), can be translated as follows: “Oh, god Nabû, strengthen by boundary pillar/my country/preserve/ defend my firstborn son!”*.

During the transition to the Neolithic, monumental stelae undoubtedly were the dominant elements of ritual complexes of Northern Mesopotamia (Kornienko, 2009). Such objects are located both at the center and along the perimeter of internal space, indicating an important difference in their social role from later Sumerian stelae and pilasters and Babylonian kudurru . Nevertheless, these Early Neolithic traditions may have influenced the later traditions of protective stelae and pilasters and kudurru.

cm

Fig. 5. Chlorite bowl with an engraved hunting scene, from a “deposit” of symbolically meaningful items in a hearth pit of an unusual Building М1b at Tell Abr-3 (after (Yartah, 2013: Fig. 173)).

the male procreative force. At the same time, they could also have designated supernatural zoomorphic and anthropomorphic deities for the communities that created these monuments. Importantly, a combination of head, phallus, human, and animal images has been manifested in the symbolic objects made by various groups and cultural complexes.

The evidence of symbolic systems of the Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic in Northern Mesopotamia thus appear to reflect not so much a “cult of the dead”, but a wider cult of totemic deities associated with specific locations and hunting-gathering societies that were shifting to sedentism. In this worldview, ancestors played an important role and were deeply connected to a group’s totem, as was the necessity of ensuring procreation and welfare of future generations through ritual.

Conclusions

As this analysis of symbolic motifs and themes indicates, it is reasonable to suggest that fertility, welfare, and procreation were important social concepts in Northern Mesopotamia during the Neolithic transition. These concepts were regularly actualized through rituals and other manifestations of symbolic behavior. It is quite probable that monumental stelae, pillars, and pilasters of the sacral complexes of this region served to represent