One Application of Ptolemy's Theorem

Автор: Nikonorov Yu.G., Oskorbin D.N.

Журнал: Владикавказский математический журнал @vmj-ru

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.27, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In this paper, we present a simple proof of one result from a recent paper by Yu. G. Nikonorov and O. Yu. Nikonorova, the original proof of which is rather cumbersome and based on the study of polynomial ideals and symbolic computations using a computer. The new proof is based on Ptolemy's theorem on inscribed quadrilaterals. In addition, other properties of inscribed quadrilaterals and related problems are considered.

Convex polygon, convex quadrilateral, extremal problems, inscribed quadrilateral, integer pentagon, perimeter, Ptolemy's theorem

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/143185222

IDR: 143185222 | УДК: 514.14 | DOI: 10.46698/o1944-0990-7792-e

Текст научной статьи One Application of Ptolemy's Theorem

In this short note, we consider elementary and short proof of one result, which was proved originally with using of symbolic computations based on the study of polynomial ideals.

1. New Proof of One Result on Special Pentagons

The following result was originally proved in [1, Theorem 4], where the proof was based on the study of polynomial ideals and symbolic computations using a computer.

Theorem 1 [1] . Let P be a convex pentagon in the Euclidean plane with the consecutive vertices A , B , C , E , F such that | AE | = | BE | = | BF | = | CF | = 1 and I AB | + | BC | > 1 . Then the perimeter L(P ) of this pentagon is not less than 3 .

In [1], the authors consider also the case when the pentagon P degenerates into a polygon with fewer sides. For example, B may degenerately lie in the segment [A, C ] , E may coincide with C or F , F may coincide with E or A . This assumption is useful since it allows to consider a compact subset of polygons in the plane with respect to the Hausdorff metric. In particular, one can be sure that there exists a pentagon with a minimum perimeter.

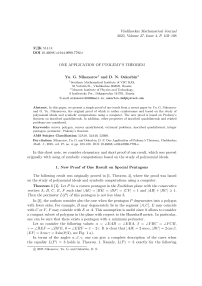

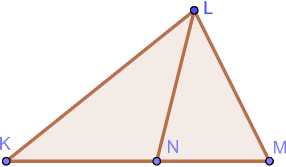

Let us consider the following values: а = Z EAB = Z EBA, в = Z FBC = Z FCB , Y = Z BEF = Z BFE, в = Z EBF = n - 2y . It is clear that | AB | = 2cos а, | BC | = 2cos в , | EF | = 2 cos y = 2sin(0/2) , see Fig. 1 a).

In terms of the angles α, β, γ , one can give a complete description of the cases when the equality L(P ) = 3 holds in Theorem 1. Namely, L(P ) = 3 exactly for the following

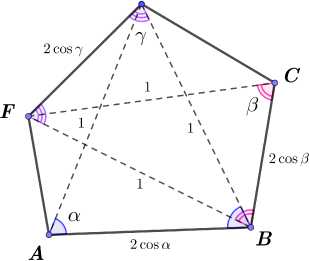

values of (a,e,Y) : (n/3,n/3,n/3) , which corresponds to E = C , F = A , | EF | = | AB | = I BC | = 1 ; (n/3,n/2,n/3) , which corresponds to B = C , A = F , | EF | = | AB | = | BE | = 1 ; (n/2, n/3, n/3) , which corresponds to B = A , C = E , | BF | = | BC | = | EE | = 1 ; (a, в, n/2) with cos(a)+cos(e) = 1 , which corresponds to a family of quadrangles with E = F and | AB | + | BC | = 1 ; (arccos(1/4), arccos(1/4), arccos(1/4)) , which corresponds to a special pentagon with perimeter 3 , see Fig. 1 b), see details in [1, Section 3].

The pentagon in Fig. 1 b) with a = в = Y = arccos(1/4) is quite remarkable. Note that Z CEB = Z CFB = Z CAB = Z AFB = Z AEB = Z ACB = Z ECF = Z EBF = Z EAF = 2arcsin(1/4) = arccos(7/8) . In particular, all vertices of this pentagon lie on the same circle. This implies | AF | = | CE | = 3/4 . Moreover, | AC | = 7/8 . Note also that the radius of the circumscribed circle is л/17 /8 . Thus, if we increase this pentagon by 8 times, we get an integer pentagon , in which all sides and diagonals have integer lengths. This pentagon was found at first in [2], see also the discussion in [3, p. 19].

E

a)

b)

Fig. 1. a) A pentagon P as in Theorem 1; b) A special pentagon P with perimeter 3 .

Here we consider a simple proof of Theorem 1, which is based on well know Ptolemy’s theorem (see the next section). In fact, the proof is also suitable for the case of a degenerate pentagon.

-

< Proof Of Theorem 1. Denote by П the perimeter of the pentagon P .

If | EF | > 1 , then, taking into account | FA | + | AB | > | FB | = 1 and | BC | + | CE | > | BE | = 1 (by the triangle inequality), we get П = | BC | + | CE | + | EF | + | FA | + | AB | > 3 . The equality here is possible only when | EF | = 1 , A E { F,B } , and C E { E,B } , i.e., P degenerates into a regular triangle with the side length 1 .

Now, we suppose that | EF | < 1 . Note that ( | AB | + | BC | — 1)(1 — | EF | ) > 0 (the equality here is equivalent to | AB | + | BC | = 1 ). Therefore,

|AB| + |BC| + |EF| — (|AB| + |BC|) • |EF| > 1.

By Ptolemy’s theorem for the quadrilateral ABEF , we get

| AB | • | EF | + | AF | = | AB | • | EF | + | AF | • | EB | > | AE | • | BF | = 1.

By Ptolemy’s theorem for the quadrilateral BCEF , we get

| BC | • | EF | + | EC | = | BC | • | EF | + | EC | • | FB | > | FC | • | EB | = 1.

The last three inequalities imply the following one:

П = |AB| + |BC| + |EC| + |EF| + |AF| = (|AB| + |BC| + |EF| - (|AB| + |BC|) • |EF|) + (|AB| • |EF| + |AF|) + (|BC| • |EF| + |EC|) > 1 + 1 + 1 = 3.

Now, we consider in detail the case when this inequality becomes the equality. It is easy to see that П = 3 if and only if | AB | + | BC | = 1 and both quadralateral ABEF and BCEF are inscribed (by Ptolemy’s theorem). Note that triangle BEF is a subset of both these quadrangles. If it is degenerate ( E = F ), then we get a 1 -parameter family of quadrangles ABCF with П = 3 . In this case, | AF | = | CF | = 1 , | AB | = t , | BC | = 1 - 1 , t G (0,1) ; for t = 0 or t = 1 , P degenerates to a regular triangle. If the triangle BEF is not degenerate, then both quadralateral ABEF and BCEF are inscribed in the circumscribed circle S for ABEF . Therefore, the pentagon P is inscribed in S . Since chords of equal length rest on equal arcs in any circle, the triangles AEB , BF C , and EBF must be equal each to other. Hence, | EF | = | AB | = | BC | = 1/2 . Therefore, we get the pentagon in Fig. 1 b). >

It should be noted that the results of the paper [1] are closely related to finding n -gons with an extreme perimeter value among all n -gons with a given self Chebyshev radius of the boundary (recall that the self Chebyshev radius of a compact set A on the Euclidean plane is the smallest radius of a circle centered within the set A that encloses A ). The study of this class of problems was initiated in [4], and some related extreme problems were solved in [5] and [6].

2. Ptolemy’s Theorem and Related Results

In Euclidean geometry, a cyclic quadrilateral or inscribed quadrilateral is a quadrilateral whose vertices all lie on a single circle. It is well known that a convex quadralateral ABCD is inscribed if and only if ^ ABC + Z CDA = n (or, equivalently, Z DAB + ^ BCD = n ). On the other hand, there are many other criterias to be inscribed for a convex quadrangle. One of the most popular and useful is the following one:

Theorem 2 (Ptolemy’s theorem) . Let Q be a convex quadrilateral in the Euclidean plane with the consecutive vertices A , B , C , D , then the sides and diagonals of Q satisfy the inequality

|AC| • |BD| < |AB| • |CD| + |BC| • |AD|, which becomes an equality if and only if Q is a cyclic quadrilateral.

There are many proofs of Ptolemy’s theorem, see e. g. [7, Problem 9.67], [8], [9, pp. 20–21].

In should be noted that | AC | • | BD | = | AB | • | CD | + | BC | • | AD | for points A,B,C,D from a straight line. It is related to the fact that the image of any circle under any inversion is either a circle or a straight line (that can be considered as a circle of infinite radius).

It is interesting the following result (which is sometimes called “Ptolemy’s second theorem”):

Theorem 3. Let Q be a convex quadrilateral in the Euclidean plane with the consecutive vertices A, B , C, D , then the sides and diagonals of Q satisfy the equality

|AC| _ |BA| • |AD| + |BC| • |CD| |BD| = |AB| • |BC| + |CA| • |AD| if and only if Q is a cyclic quadrilateral.

This result was obtained independently in [8] and [10], see some details in [9, pp. 24–25].

Note that many other results are known related to quadrangles inscribed in a circle. The interested reader can be advised to read the papers [9] and [11] on this topic.

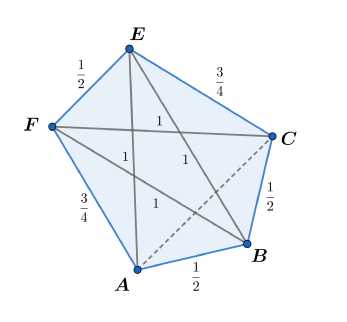

Finally, we consider one result obtained by A. Mannheim in [12], see also [13] and [14, Appendix 3], see Fig. 2 a).

a)

b)

Fig. 2. a) Mannheim’s theorem; b) Stewart’s theorem.

Theorem 4 (Mannheim’s theorem) . Let ABCD be a convex cyclic quadrilateral ( with consecutive vertices) in some Euclidean plane E 2 , that is situated in 3 -dimensional Euclidean space E 3 . Then for any point O ∈ E 3 , we have the following equality:

I AB I • | BD | • | AD | • I OC | 2 + I BC | • | CD | • | BD | • | OA | 2 = | AB | • I BC | • I AC | • | OD | 2 + I AC | • | CD | • | AD | • | OB | 2 .

If we take O := A in this theorem, then we get | AC | • \ BD \ = I AB I • \ CD \ + \ BC | • | AD | , the equality in Theorem 2. On the other hand, if we take the center of the circumscribed circle as the point O , then | OA | = | OB | = | OC | = | OD | and we get the equality in Theorem 3.

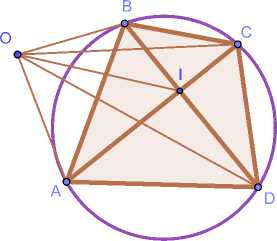

For the convenience of readers, we will present a proof of Theorem 4. The simplest way to prove this theorem is to use one standard result which is known as Stewart’s theorem, see Fig. 2 b).

Lemma 1 (Stewart’s theorem) . Let AKLM be a convex triangle in the Euclidean plane, and N is a point of the side KN . Then we have the following equality:

I LN | 2 = | KL | 2 • j NM + I LM | 2 • ^KN - | KN | • I NM | .

| KM | | KM |

<1 If we express cos Z LKM from the triangles KLM and KLN , then we get

2-|KLI- ,LKM = IKL + ^M 2 ^ |KM|

| KL | 2 + | KN | 2 - | LN | 2 | KN |

that easily implies what we want. ⊲

⊳ Proof of Theorem 4. We use a little modified arguments from [13]. Let I be the intersection point of the diagonals AC and BD . Applying Lemma 1 to the triangles AOC and BOD with points on the sides AC and BD , we get

I OI I 2 = | OA | 2 • C I + I OC I 2 • [ AC — I AI । • I IC I , (1)

| OI | 2 = | OB | 2 • + | OD | 2 • И - | BI | • | ID | . (2)

| BD | | BD |

Since the quadrilateral ABCD is inscribed, then ^ DAC = Z DBC and Z BAC = Z BDC. This implies that A AID is similar to ABID, as well as, ABIA is similar to ACID. These observations imply that

| AI | | DI | | AD | | AI | | BI | | AB |

| BI | | CI | I BC |, | DI | | CI | | CD | ■ ( )

In particular, | AI | • | IC | = | BI | • | ID | . Hence, (1) and (2) imply

2 | AI | 2 | CI | 2 | BI | 2 | DI |

|OA| | AC | + | OC | | AC | |OB| \ BD \ + | OD | | BD | and

| BD | • (|OA | 2 • | AI | + | OC | 2 • | CI|) = | AC | • (|OB | 2 • | BI | + | OD | 2 • | DI|) . (4)

We get from (3), that

| AB | | BC | | AB | | AB | | BC |

= i CDT | DI | • | CI | = i AD i•\ DI• \ BI | = T CD T'| CI | = | CD |\ AD \ ■ 1 DI.

Substituting the obtained expressions into (4), we complete the proof. ⊲