Origin of the Andronovans: A Statistical Approach

Автор: Kozintsev A.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Anthropology and paleogenetics

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The origin of the Andronovo population is explored using a statistical rather than typological approach. Four questions are raised. Which Eastern European populations of the Middle Bronze and the transition to the Late Bronze Age had taken part in Andronovo origins? What was the contribution of the southern groups? What was the role of the autochthonous Siberian substratum? What was the population background of the dichotomy between two major Andronovo cultural traditions, Fedorovka and Alakul? To address these questions, measurements of 12 male Andronovo cranial samples (nine relating to Fedorovka and three to Alakul) and 85 male cranial samples from Eastern Europe, Siberia, Kazakhstan, Southwestern Central Asia, Southern Caucasus, and the Near East were subjected to canonical variate analysis, and minimum spanning trees were constructed. The results suggest that the most likely ancestors of Andronovans were Late Catacomb tribes of Northern Caucasus, people of Poltavka, Sintashta, and those associated with the Abashevo-Sintashta horizon. While no direct parallels with Southern Caucasian, Southwestern Central Asian or Near Eastern populations were found among Andronovo groups, some of them could have inherited the southern component from either the Abashevo or the Catacomb people. In the former case, one should postulate a gradient: Fatyanovo → Balanovo → Abashevo → Sintashta → Petrovka → Andronovo; in the latter case, the variation within Andronovo is directly derivable from that among the Catacomb populations. Andronovo groups displaying an autochthonous Siberian tendency demonstrate various degrees of “mutual assimilation” between immigrants and pre-Mongoloid natives. Differences between the Fedorovka and Alakul samples are significant but very small. A special role of Petrovka in the origin of Alakul is not supported by the analysis.

Southern Siberia, Eastern Europe, Late Bronze Age, Andronovo culture, Fedorovka tradition, Alakul tradition

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146965

IDR: 145146965 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.4.142-151

Текст научной статьи Origin of the Andronovans: A Statistical Approach

The origin of the Andronovo people remains somewhat enigmatic. This general problem consists of several partial ones. First, which Eastern European populations of the Middle Bronze Age and the transition to the Late Bronze Age had taken part in Andronovo origins? Second, what was the contribution of the southern (Southern Caucasian, Southwestern Central Asian, and Near Eastern) groups? Third, what was the role of the autochthonous Siberian substratum? Fourth, what was the population background of the two major Andronovo cultural traditions, Fedorovka and Alakul?

The first problem can be examined on the basis of cranial material that has appeared in the recent years and relates to the Poltavka, Sintashta, and Petrovka cultures, as well as to the Abashevo-Sintashta horizon (see below).

I have already tried to answer the second question, stating that migration impulses resulting in the emergence of the Andronovo population had originated in Eastern

Europe (including Northern Caucasus) and Central Europe, and that physical anthropology provides no grounds whatever for speaking of migrations from the south (Kozintsev, 2008, 2009, 2017). This evoked criticism: gracile Andronovo (Fedorovka) “Mediterraneans” of the Altai reveal, as the critics claim, Southern Caucasian parallels (Kiryushin, Solodovnikov, 2010), which they ascribe to the Samus-Yelunino substratum. Dental anthropology and cranial nonmetrics, too, have revealed southern (typologically “Mediterranean”) traits in those people (Tur, 2009, 2011). The same tendencies were found by A.A. Kazarnitsky (2012: 141–143) in Middle and Late Bronze Age populations of Kalmykia, some of which were shown to be likely ancestors of Andronovans (Kozintsev, 2009). Kazarnitsky was the first to note that in the Bronze Age, maximal cranial gracility was found not in the south (in Southern Caucasus), but in the west—in Central and Western Europe. Among the samples he studied, the most gracile ones resemble those from Southern Caucasus. “This allows us”, he writes (Ibid.: 141), “to reject with a fair degree of certainty the idea that Western European groups had taken part in the origin of Middle and Late Bronze Age populations of the northwestern Caspian (Shevchenko, 1986)”. All the above appears to uphold the key role of the southern impulse in the Andronovo origin, too. Isn’t it time for me to admit that I was wrong?

I wouldn’t hesitate to do that, were it not for genetics, which unambiguously points to the western rather than southern source of migrations resulting in the origin of Sintashta, Petrovka, Andronovo, and Srubnaya populations. Two thirds of their gene pool were inherited from the steppe populations of the Early and Middle Bronze Age, and one third from the Corded Ware groups. This conclusion, based on the genome-wide analysis (Narasimhan et al., 2019), forced K.N. Solodovnikov and A.V. Kolbina (2018) to accept the importance of the Central European component in the formation of Sintashta (and, consequently, Andronovo) populations, whereas A.A. Khokhlov and E.P. Kitov (2019) have remained unconvinced. Therefore, one should revisit cranial materials and try to understand the reason of the controversy.

The third question, about the autochthonous Siberian component, has become much clearer after T.A. Chikisheva (2012: 69–72, 98–101, 113–115) had introduced new cranial samples from the Baraba foreststeppe (see also (Chikisheva, Pozdnyakov, 2003, 2019)).

The fourth question, concerning the nature of differences between Fedorovka and Alakul, can also be revisited with the help of new materials, since now we have as many as 12 Andronovo samples—nine from Fedorovka burials, and three from those associated with the Alakul tradition. A special focus of interest is the Petrovka sample, because some view Petrovka as early Alakul (Tkachev, 2003; Vinogradov, 2011: 141).

Materials and methods

For a complete analysis (statistical and graphical), measurements of 58 male cranial samples were used, relating to the following cultures, periods, and territories of Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Eastern Europe*:

-

1. Andronovo (Fedorovka) culture, Central, Northern, and Eastern Kazakhstan (Solodovnikov, Rykun, Loman, 2013)**;

-

2. Same, Baraba forest-steppe (Chikisheva, 2012: 12, 113–115);

-

3. Same, Rudny Altai (Kiryushin, Solodovnikov, 2010);

-

4. Same, Barnaul stretch of the Ob, Firsovo XIV

-

5. Same, Barnaul-Novosibirsk stretch of the Ob (Ibid.);

-

6. Same, Chumysh River (Ibid.);

-

7. Same, Tomsk stretch of the Ob, Yelovka II (Solodovnikov, Rykun, 2011);

-

8. Same, Kuznetsk Basin (Chikisheva, Pozdnyakov, 2003);

-

9. Same, Minusinsk Basin (Solodovnikov, 2005);

-

10. Andronovo (Alakul-Kozhumberdy) culture, Southern Urals and Western Kazakhstan (Khokhlov, Kitov, Kapinus, 2020);

-

11. Andronovo (Alakul) culture, Central, Northern, and Eastern Kazakhstan (Solodovnikov, Rykun, Loman, 2013)***;

-

12. Same, Omsk stretch of the Irtysh, Yermak IV (Dremov, 1997: 83, 85);

-

13. Yamnaya-Catacomb group, Kalmykia (Kazarnitsky, 2012: 77);

-

14. Early Catacomb culture, Kalmykia (Ibid.: 69);

-

15. Same, Lower Dnieper, Verkh-Tarasovka (Kruts, 2017: 68, and unpublished);

-

16. Same, Kakhovka (Ibid.);

-

17. Same, Northwestern Azov, Molochnaya River (Ibid.);

-

18. Catacomb culture, Stavropol (Romanova, 1991);

-

19. Same, Southern Kalmykia, Chogray (Kazarnitsky, 2011: 75);

-

20. Same, Northern Kalmykia (Kazarnitsky, 2012: 91);

-

21. Same, Volga Basin (Shevchenko, 1986);

Averages and standard errors of traits in the Abashevo-Sintashta and Sintashta male cranial samples

Traits

Abashevo-Sintashta

Sintashta

N

M

SE

N

M

SE

1. Cranial length

6

185.5

3.9

18

188.1

1.7

8. Cranial breadth

6

139.3

2.7

18

138.0

1.3

8:1. Cranial index

6

75.2

1.2

16

73.9

1.0

17. Cranial height

5

131.8

3.3

14

137.9

1.9

9. Minimal frontal breadth

6

97.8

2.0

21

98.2

0.9

45. Bizygomatic breadth

5

135.8

4.7

11

138.7

1.7

48. Upper facial height

5

67.0

2.8

17

71.5

1.0

55. Nasal height

6

50.2

1.3

17

51.6

0.7

54. Nasal breadth

6

24.0

0.5

16

24.5

0.3

51. Orbital breadth (mf)

5

42.6

1.3

15

42.9

0.4

52. Orbital height

5

32.0

1.1

17

32.1

0.4

77. Naso-malar angle

6

135.5

1.4

16

137.3

0.9

∠ zm’. Zygo-maxillary angle

6

130.3

2.3

13

127.5

1.4

SS : SC. Simotic index

6

45.3

2.4

15

58.0

3.2

75 (1). Nasal protrusion angle

5

28.2

2.3

18

32.7

1.6

Note . N – number of observations, M – mean, SE – standard error.

-

22. Same, Lower Volga (Khokhlov, 2017: 282–283);

-

23. Same, Don Basin (Shevchenko, 1986);

-

24. Same, Crimea (Kruts, unpublished);

-

25. Same, Lower Dnieper, Kherson (Ibid.);

-

26. Same, Zaporozhye (Kruts, 2017: 68, and unpublished);

-

27. Same, Kakhovka (Ibid.);

-

28. Same, Krivoy Rog (Kruts, unpublished);

-

29. Same, Lower Dnieper, Verkh-Tarasovka (Kruts, 2017: 68, and unpublished);

-

30. Same, Samara-Orel watershed (Kruts, unpublished);

-

31. Same, Yuzhny Bug-Ingulets watershed (Ibid.);

-

32. Fatyanovo culture, Central Russia (Denisova, 1975: 94);

-

33. Balanovo culture, Chuvashia, Balanovo (Akimova, 1963);

-

34. Abashevo culture, Mari El, Pepkino (Khalikov, Lebedinskaya, Gerasimova, 1966: 39–42);

-

35. Poltavka culture, Samara stretch of the Volga and the Volga steppe (Khokhlov, 2013: 187–188);

-

36. Babino (Multi-Cordoned Ware) culture, Dnieper steppes (Kruts, 1984: 48, 50);

-

37. Lola culture, Northern Caucasian steppes (Kazarnitsky, 2012: 112);

-

38. Krivaya Luka cultural group, Middle Volga (Khokhlov, 2017: 275–276);

-

39. Abashevo-Sintashta horizon, Volga-Ural foreststeppe (Khokhlov, Grigoryev, 2021). Averages and standard errors (see Table ) were calculated after individual data (Ibid.);

-

40. Sintashta culture, Volga-Ural area (Potapovka type burials) and Eastern Urals. Averages and standard errors

(see Table ) were calculated after individual data published by G.V. Rykushina (2003) and relating to Krivoye Ozero, E.P. Kitov (2011: 71) relating to Bolshekaragansky, and A.A. Khokhlov (2017: 286–293) relating to Potapovka I, Utevka VI, Grachevka I, Krasnosamarsky IV, Tanabergen II, and Bulanovo I. Crania from Potapovka 2-1, 2-2-1, 2-2-2, and 5-16, which are earlier (Otroshchenko, 1998), and those from burials 4 and 9 at Bulanovo with Seima-Turbino artifacts (Khalyapin, 2001; Khokhlov, 2017: 100) were excluded;

-

41. Petrovka culture, Southern Urals and Northern Kazakhstan (Kitov, 2011: 74–75);

-

42. Okunev culture, Khakas-Minusinsk Basin, Tas-Khazaa (Gromov, 1997);

-

43. Same, Uybat (Ibid.);

-

44. Same, Chernovaya (Ibid.);

-

45. Same, Verkh-Askiz (Ibid.);

-

46. Karakol culture, Gorny Altai (Tur, Solodovnikov, 2005);

-

47. Chaa-Khol culture, Tuva (Gokhman, 1980);

-

48. Yelunino culture, Upper Ob (Solodovnikov, Tur, 2003);

-

49. Samus culture, Tomsk-Narym stretch of the Ob (Solodovnikov, 2005)*;

-

50. Chemurchek culture, Western Mongolia (Solodovnikov, Tumen, Erdene, 2019);

-

51. Ust-Tartas culture, Baraba forest-steppe, Sopka-2/3 (Chikisheva, 2012: 69–72);

-

52. Same, Sopka-2/3A (Ibid.);

-

53. Odino culture, Sopka-2/4A (Ibid.: 98–101);

-

54. Same, Tartas-1 (Chikisheva, Pozdnyakov, 2019);

-

55. Same, Preobrazhenka-6 (Ibid.);

-

56. Krotovo culture, classic stage, Sopka-2/4B, C (Chikisheva, 2012: 98–101);

-

57. Late Krotovo (Cherno-Ozerye) culture, Sopka-2/5 (Ibid.);

-

58. Same, Omsk stretch of the Irtysh, Cherno-Ozerye-1 (Dremov, 1997: 83, 85).

(Ibid.);

Also, to address the question of southern affinities of the Andronovans, measurements of 39 samples from the Caucasus, Southwestern Central Asia, and the Near East were employed*.

Early Bronze Age groups—those associated with the Yamnaya and Afanasyevo cultures—were not included because of the chronological gap separating them from Andronovo. In theory, admittedly, descendants of Afanasyevans could have survived in certain areas of Southern Siberia for several centuries and provided a substratum for the Andronovo populations. V.P. Alekseyev (1961) even regarded the Afanasyevans of the Altai as ancestors of all Andronovans, which is hard to accept today. However, the Andronovo (Fedorovka) people of Firsovo XIV and Rudny Altai are indeed indistinguishable from the Afanasyevans of Saldyar in Gorny Altai (Kozintsev, 2009). The similarity is all the more impressive because of territorial proximity of those groups, so one needn’t postulate any migrations. And still, there are no direct indications that descendants of Afanasyevans had survived until the Andronovo age. Also, Afanasyevans are very similar to Catacomb people (Kozintsev, 2009, 2020), so caution must be applied when assessing such parallels.

The trait battery includes 14 principal measurements: cranial length, breadth, and height, minimal frontal breadth, bizygomatic breadth, upper facial height, nasal and orbital height and breadth, naso-malar and zygo-maxillary angles, simotic index, and nasal protrusion angle. Measurements were processed with canonical analysis, Mahalanobis’ distances corrected for sample size ( D2 c ) were calculated, and minimum spanning trees (MST), showing the shortest path between group centroids on the plane generated by two canonical variates, were constructed. The latter method, unlike cluster analysis, is optimal for revealing gradients*. B.A. Kozintsev’s package CANON and Ø. Hammer’s package PAST (version 4.05) were used.

Obviously, being stochastic, the conclusions of this study need to be verified by archaeological and genetic data.

Results

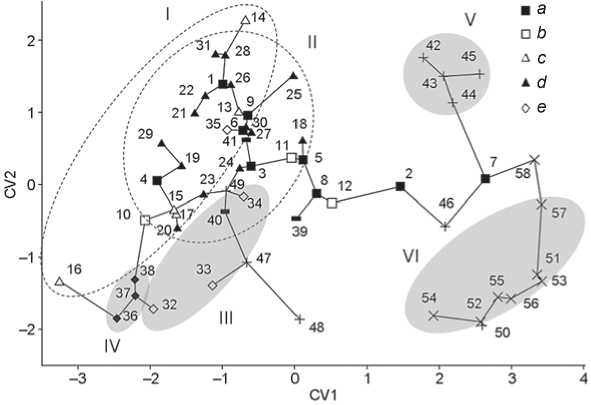

Andronovans versus Eastern European groups of the Middle and transition to the Late Bronze Age. Fig. 1 shows the arrangement of 58 populations included in the principal analysis on the plane of the first two canonical vectors, describing 68 % of the total variation. Close ties between Andronovans and Catacomb people are evident: most Andronovo samples (No. 1, 3–6, and 8–11) are either within the Catacomb cluster, occupying most of the left half of the graph, or close to it. The same applies to the Poltavka and Petrovka samples (No. 35 and 41). Three postCatacomb samples—Babino (No. 36), Lola (No. 37), and Krivaya Luka (No. 38)—differ from all Andronovo and Catacomb ones, except the early Catacomb sample from Kakhovka (No. 16), by being very gracile (typologically “Mediterranean”). The Corded Ware cluster is markedly stretched. Its most gracile group, Fatyanovo (No. 32), is close to the post-Catacomb samples; Abashevo (No. 34) displays a Catacomb-Andronovo tendency; and Balanovo (No. 33) is intermediate. The Sintashta group (No. 40) falls inside the Corded Ware cluster, while being actually closer to certain Catacomb and Yamnaya samples than to those associated with the Corded Ware tradition (see below). Four Andronovo samples (No. 2, 7, 8, and 12) exhibit a shift toward Siberian autochthones (see below). One of them, in which this tendency is relatively weak (No. 8, from the Kuznetsk Basin) is connected with Abashevo-Sintashta (No. 39) by the MST edge.

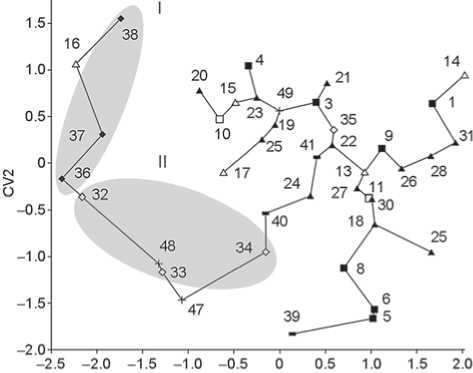

To better understand the nature of variation in European groups, we will exclude three Andronovo samples, in which the native Siberian tendency is the strongest (No. 2, 7, and 12), as well as all the presumably autochthonous Siberian populations (No. 42–46 and 50– 58), and repeat the analysis for the remaining samples (Fig. 2). Although the two new canonical variates now account for only a half (53 %) of the total variation, the pattern has become clearer. The Corded Ware cluster is now separated from the Catacomb-Andronovo one. The Sintashta group (No. 40) is no longer within the former, being shifted towards Catacomb and Andronovo samples. Yelunino (No. 48), on the other hand, joins the Corded Ware groups, despite being actually close only to Chaa-Khol (No. 47). Poltavka (No. 35) and Petrovka (No. 41), as before, are in the center of the Catacomb-Andronovo cluster.

Let us estimate the mean differences between the 12 Andronovo groups and ten others, whose role in Andronovo origin is the most probable on the basis of

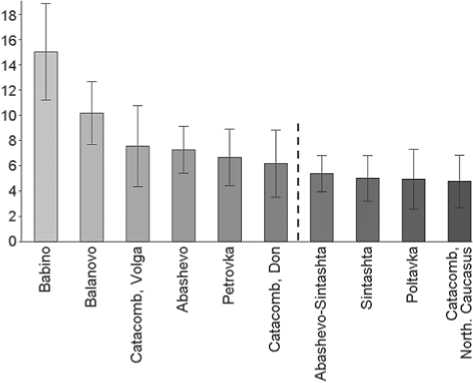

♦f

-g

+h

i

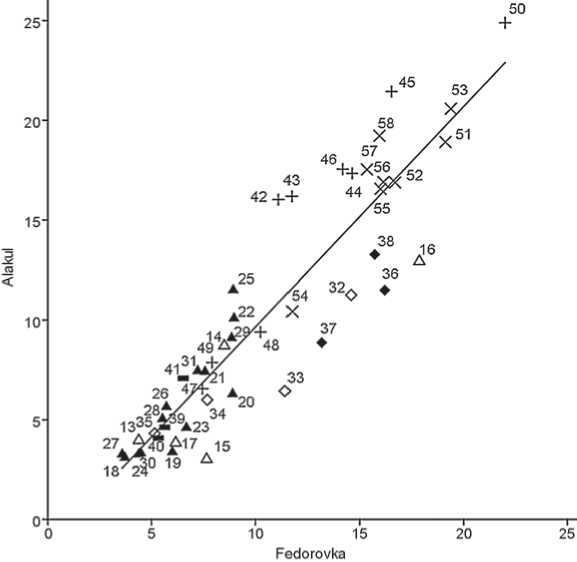

Fig. 1. Position of male cranial samples on the plane of two canonical variates, CV1 and CV2.

Straight lines are edges of the minimum spanning tree, showing the shortest path between group centroids on the plane. Dashed contours and spots show groupings based on archaeological criteria : I – Early Catacomb; II – Late Catacomb; III – Corded Ware; IV – post-Catacomb; V – Okunev; VI – Baraba native Siberian. a – Fedorovka; b – Alakul; c – Early Catacomb; d – Late Catacomb; e – other Middle Bronze Age groups; f – postCatacomb; g – other groups transitional between Middle and Late Bronze Age; h – Okunev and Okunev type; i – Baraba native Siberian. See text for group numbers.

archaeological, genetic, and geographic criteria, namely three Late Catacomb groups—those from Northern Caucasus (No. 18–20, pooled), Volga (No. 21) and Don (No. 23), Balanovo (No. 33), Abashevo (No. 34), Poltavka (No. 35), Babino (No. 36), Abashevo-Sintashta (No. 39), Sintashta (No. 40), and Petrovka (No. 41). Because variation within Andronovo is important, the distance of each Andronovan sample and each of the ten others was regarded as one observation. In each of the following cases, therefore, ranked in the decreasing order of mean D2 с (i.e., in the increasing order of similarity), the sample consists of 12 observations, which were used to calculate the average distance, its error, and the 95 % confidence interval (Fig. 3):

CV1

Fig. 2. Position of male cranial samples on the plane of two canonical variates, CV1 and CV2. Native Siberian groups and Andronovo samples with a native Siberian tendency are excluded.

Cultural groupings shown by spots: I – post-Catacomb; II – Corded Ware. See Fig. 1 for explanations.

Babino – 15.03 ± 1.95;

Balanovo – 10.17 ± 1.27;

Catacomb (Volga) – 7.55 ± 1.64;

Abashevo – 7.26 ± 0.95;

Petrovka – 6.66 ± 1.15;

Catacomb (Don) – 6.18 ± 1.35;

Abashevo-Sintashta – 5.38 ± 0.73;

Sintashta – 5.01 ± 0.91;

Poltavka – 4.94 ± 1.20;

Catacomb (Northern Caucasus) – 4.75 ± 1.05.

The general comparison of all these estimates shows that the differences are highly significant: according to ANOVA, F = 19.6, d.f. = 9; 110, p < 0.001; according to the nonparametric Friedman test, χ 2 = 53.8, d.f. = 9, p < 0.001. The pairwise comparison of mean distances using the parametric Tukey test shows that the Babino sample is significantly further from those of Andronovo than the remaining ones, whereas Balanovo is further from Andronovo than any of the six samples of the right flank, beginning from Petrovka. The Wilcoxon nonparametric test is more informative, showing that differences between all the groups, except the last four, are significant. Precisely these four groups, therefore—Catacomb from Northern Caucasus, Poltavka, Sintashta, and Abashevo-Sintashta—are closest to Andronovo samples.

The role of the southern component . In this case, there is no need to construct any graphs—it suffices to simply compare each of the 12 Andronovo samples with each of the 39 southern ones (see above). How many Southern Caucasian, Southwestern Central Asian, and Near Eastern groups, then, are close to those associated with the Andronovo culture ( D2 c < 1)?

Fedorovka tradition, Central, Northern, and Eastern Kazakhstan – none;

same, Baraba forest-steppe – Dashti-Kazy (Tajikistan, Upper Zarafshon) (Khodjayov, 2004);

same, Rudny Altai – Dashti-Kazy;

Fig. 3. Average distances ( D2 с ) between 10 Middle and transitional to Late Bronze Age samples and 12 Andronovo groups with 95 % confidence intervals.

same, Barnaul stretch of the Ob, Firsovo XIV – none; same, Barnaul-Novosibirsk stretch of the Ob – none; same, Chumysh – none;

same, Tomsk stretch of the Ob, Yelovka II – none;

same, Kuznetsk Basin – Dashti-Kazy;

same, Minusinsk Basin – none;

Alakul-Kozhumberdy tradition, Southern Urals, and Western Kazakhstan – none;

Alakul tradition, Central, Northern, and Eastern Kazakhstan – none;

same, Omsk stretch of the Irtysh, Yermak IV – Dashti-Kazy.

We will return to the late sample from Dashti-Kazy in the Discussion. The Yelunino group is far from all Andronovo groups and doesn’t display a single southern parallel. The Samus sample is close to only one Andronovo group—that from Rudny Altai, and likewise shows no southern affinities. By contrast, Firsovo XIV, Rudny Altai, and Alakul-Kozhumberdy are in the very midst of Catacomb groups (see Fig. 2), being also close to a number of Yamnaya and Srubnaya ones. The first reveals five very close Yamnaya and Catacomb parallels; the second, seven; and the third, whose purportedly southern ties were the subject of prolonged and heated debates (for a review, see (Kozintsev, 2017)), likewise seven.

The aboriginal Siberian component . Let us return to Fig. 1. As noted above, four Andronovo samples exhibit a marked eastern shift. They are arranged in a gradient along the first canonical vector, the eastern traits increasing in the following order: Fedorovka from the Kuznetsk Basin (No. 8) → Alakul from Yermak IV in the Omsk stretch of the Irtysh (No. 12) → Fedorovka from the Baraba forest-steppe (No. 2) → Fedorovka from Yelovka II in the Tomsk stretch of the Ob (No. 7). Whereas the Kuznetsk sample is not far from, say, the Catacomb group of Stavropol (No. 18), Yelovka is rather close to the morphologically “easternmost” groups such as Andronovo from Cherno-Ozerye (No. 58), and Late Krotovo from Sopka 2/5 (No. 57). Halfway between the Fedorovka-type Andronovans of the Baraba forest-steppe and Yelovka II, along the first canonical vector, is the Karakol sample (No. 46). The further accretion of eastern traits terminates abruptly, and the pattern acquires an entirely different meaning, mirrored by the second canonical vector. Here, the Andronovans of Baraba and Tomsk are intermediate between the Okunev people (whom T.A. Chikisheva attributes to

the Southern Eurasian Formation) and the autochthonous Neolithic and Bronze Age populations of Baraba, which, in her view, exemplify the Northern Eurasian Formation; close to which are the Chemurchek people of Mongolia (No. 50).

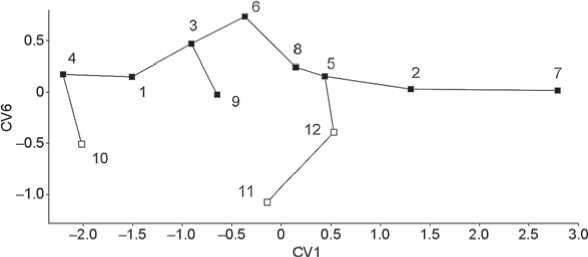

Fedorovka versus Alakul . It appears impossible to discern any regularity in the position of Fedorovka and Alakul samples on the graphs (see Fig. 1, 2). To approach this problem in more detail, we will confine the analysis to Andronovo groups. As it turns out, the Fedorovka people differ from those of Alakul only on the sixth canonical variate. Its mean value in nine Fedorovka groups is -0.217 ± 0.082; in three Alakul groups, 0.659 ± 0.210, and there is no overlap (Mann-Whitney p = 0,016). But even if this vector is artificially separated, the opposition between Fedorovka and Alakul is quite indistinct (Fig. 4). Traits with the highest loadings on CV6 are cranial and nasal height, and those with opposite signs, upper facial height and nasal breadth. But capturing such a structure of relationships by means of simple indices (vertical facio-cerebral and nasal) proves impossible, because the share of variation explained by CV6 is too small, only 2.7 %.

Fig. 4. Position of male Fedorovka and Alakul samples on the plane of the first and sixth canonical variates.

See Fig. 1 for explanations.

Fig. 5 . Correlation between average distances of Fedorovka and Alakul groups from others.

See Fig. 1 for explanations.

hand, while Andronovans are opposed to the Sintashta and Abashevo people (let alone those of Balanovo and Fatyanovo), being connected with them only by a gradient, their close connection with the Catacomb and Poltavka people is direct, without any gradients (See Fig. 2, 3).

Interpreting the differences between the Andronovo groups (except those revealing an autochthonous Siberian tendency, see below) is no easier than understanding the geographic and chronological differences between the Catacomb samples. Only one thing is apparent: in terms of craniometry alone, the variation within Andronovo is fully derivable from that within the Catacomb community. The same applies to the problem of the southern component. Postulating Southern Caucasian affinities of the Andronovans of the Altai was as futile as searching for the sources of the Alakul-Kozhumberdy population in Southwestern Central Asia. I must reiterate my earlier claim: no direct southern parallels have been detected for any Andronovo group. Or rather, to be more precise, there is one single parallel—with an immigrant population

The correlation between average distances ( D2 c ) of the Fedorovka and Alakul groups from 46 others (Fig. 5) is quite strong ( r s = 0.92, p < 0.001), demonstrating yet again that differences between them are very small. If the analysis is confined to ten groups selected on extra-anthropological grounds (see above), the coefficient of rank correlation drops to 0.83 ( p = 0.003). The largest disagreement concerns the Petrovka group, which, on average, is closer to Fedorovka samples (6.52) than to those associated with Alakul (7.08), although certain archaeologists view Petrovka as early Alakul.

Discussion

The relative contribution of Eastern European populations to the origins of Andronovo is far from being well understood. On the one hand, Fig. 2 reveals a vector, along which the samples are arranged in the following succession: Fatyanovo → Balanovo → Abashevo → Sintashta → Petrovka → Andronovo, which agrees with geographic, archaeological, and genetic facts (Nordqvist, Heyd, 2020: 20, fig. 11). Admittedly, the special role of Petrovka as an immediate precursor of Alakul is not supported by the analysis. Fig. 2 shows a continuity between Abashevo-Sintashta and the subcluster of Fedorovka samples from the Barnaul-Novosibirsk area, the Chumysh, and the Kuznetsk Basin. On the other associated with the intrusive culture of the Steppe Bronze, attested by burials at Dashti-Kazy in Tajikistan (Khodjayov, 2004). This late and sharply heterogeneous group, dating to 1200–1000 BC and apparently resulting from a mechanical admixture of highly dissimilar individuals (aborigines and people of steppe descent), has no bearing on our topic.

As for the indirect ties of Andronovans with the south, if the presumed (but unconfirmed) Yelunino substratum is disregarded, two possibilities remain. One is that Andronovans had received the southern component from the Corded Ware people, as suggested by the genomewide analysis (Narasimhan et al., 2019). Certain physical anthropologists accepted this idea (Solodovnikov, Kolbina, 2018), while others rejected it (Khokhlov, Kitov, 2019). What do cranial data suggest? The gradient Fatyanovo → Balanovo → Abashevo → Sintashta → Petrovka → Andronovo (Fig. 2) is easy to understand. An intense influx of southern genes to Europe from the Near East with the spread of farming is a well-known fact, accounting for A.A. Kazarnitsky’s findings (see above). During the Middle and Late Bronze Age, the southern component gradually decreased on its way from Central Europe to the Urals, being replaced by the steppe component (Narasimhan et al., 2019).

The second possibility is that Andronovans had inherited southern affinities from the Catacomb people, who are cranially very close to them. Dental data suggest likewise (see (Zubova, Chikisheva, Pozdnyakov, 2014)). The Catacomb people, on the other hand, could have received the southern genes both directly from Southern Caucasus (Kazarnitsky, 2012: 141, 143) and indirectly, with the Yamnaya legacy (for the origin of the southern component in the Yamnaya population, see (Anthony, 2019; Kozintsev, 2019)). If “the origin of cultures transitional between the Middle and Late Bronze Age <…> should be viewed in the context of a general destruction and dissociation of the Corded Ware, Catacomb, and Abashevo communities” (Litvinenko, 2003: 148), then, in the case of Andronovans, it suffices to assume that the “strong underlying Catacomb substratum” (Ibid.) turned out to be stronger than that of Abashevo-Corded Ware. Geneticists point to the importance of the Yamnaya contribution to Sintashta and Andronovo, but they did not examine the Catacomb component, which is close to Yamnaya.

As regards Andronovo groups displaying an autochthonous Siberian tendency, what we deal with here is not “Mongoloid admixture”, as commonly assumed, but various stages of “mutual assimilation” of immigrants and pre-Mongoloid autochthonous populations of Siberia (Chikisheva, 2012: 123; Kozintsev, 2021). The share of the aboriginal component is relatively minor in Fedorovka people of the Kuznetsk Basin and the Alakul people of the Omsk Irtysh area (Yermak IV). It is much higher in Fedorovka people of the Baraba forest-steppe and especially the Tomsk stretch of the Ob (Yelovka II), who resemble those associated with the natives of Cherno-Ozerye, culturally influenced by Andronovans, and the Karakol people, whose western traits have a pre-Andronovo origin. Interestingly, the Yelovka II group is the earliest known population displaying a “Uralian” combination of craniometric and cranial nonmetric traits, apparently evidencing the southward spread of the Uralic speakers from the taiga to the sub-taiga belt (Kozintsev, 2004, 2021).

Differences between the Fedorovka and Alakul groups are inappreciable as compared to those within them, indicating common origin. The same conclusion was reached by dental anthropologists, who ascribe the differentiation between these two traditions to social factors (Zubova, Chikisheva, Pozdnyakov, 2014), and even earlier by O.N. Korochkova (1993). The nature of those factors remains a matter of guesswork.

Conclusions

-

1. The most likely ancestors of Andronovans are Late Catacomb people of Northern Caucasus, as well as those associated with Poltavka, Sintashta, and the Abashevo-Sintashta horizon.

-

2. Andronovans display no direct southern (“Mediterranean”) affinities. But they could have

-

3. Andronovo groups showing an autochthonous Siberian tendency demonstrate various stages of “mutual assimilation” between the immigrants from the west and the pre-Mongoloid natives of Siberia.

-

4. Interpreting the cultural division between the two Andronovo traditions—Fedorovka and Alakul—in terms of physical anthropology is impossible. Apparently, they had a common origin.

received the southern component indirectly either from the Catacomb or from the Abashevo people.

Acknowledgement

I am thankful to K.N. Solodovnikov and the late S.I. Kruts for granting me access to their unpublished data.