Pit-grave (Yamnaya) and pit-grave-maikop burials at Levoyegorlyksky-3, Stavropol

Автор: Korenevskiy S.N., Kalmykov A.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145356

IDR: 145145356 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.1.086-099

Текст обзорной статьи Pit-grave (Yamnaya) and pit-grave-maikop burials at Levoyegorlyksky-3, Stavropol

It is well known that the tribes of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya cultural community (MNC) exerted great influence on their northern neighbors—the carriers of the Pit-Grave culture of the northern Caucasus and the Kuma-Manych Depression (Merpert, 1974: 153, fig. 1, II; Korenevskiy, 2004: 93–96). However, we do not yet have a sufficient number of sources with information on the contacts of these two most important components of the population of the northern Caucasus in the fourth millennium BC. Thus, every new discovery in this field deserves special consideration. This article analyzes burials of the Pit-Grave culture, associated with the stage of the emergence and early function of burial mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3 cemetery, which reflects this cultural interaction.

Excavation materials

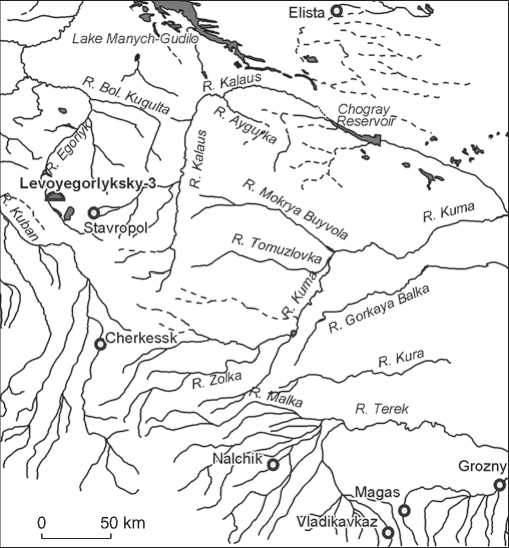

Levoyegorlyksky-3 cemetery is located in Izobilnensky District of the Stavropol Territory, on the left bank of the Yegorlyk River (a reservoir was made in this area) (Fig. 1). Initially, this cemetery consisted of seven mounds, which were set up in a line along the ridge of the spur of Mount

Verblyud, descending to the river. The total length of the cemetery is approximately 450 m; the elevation difference is about 13 m.

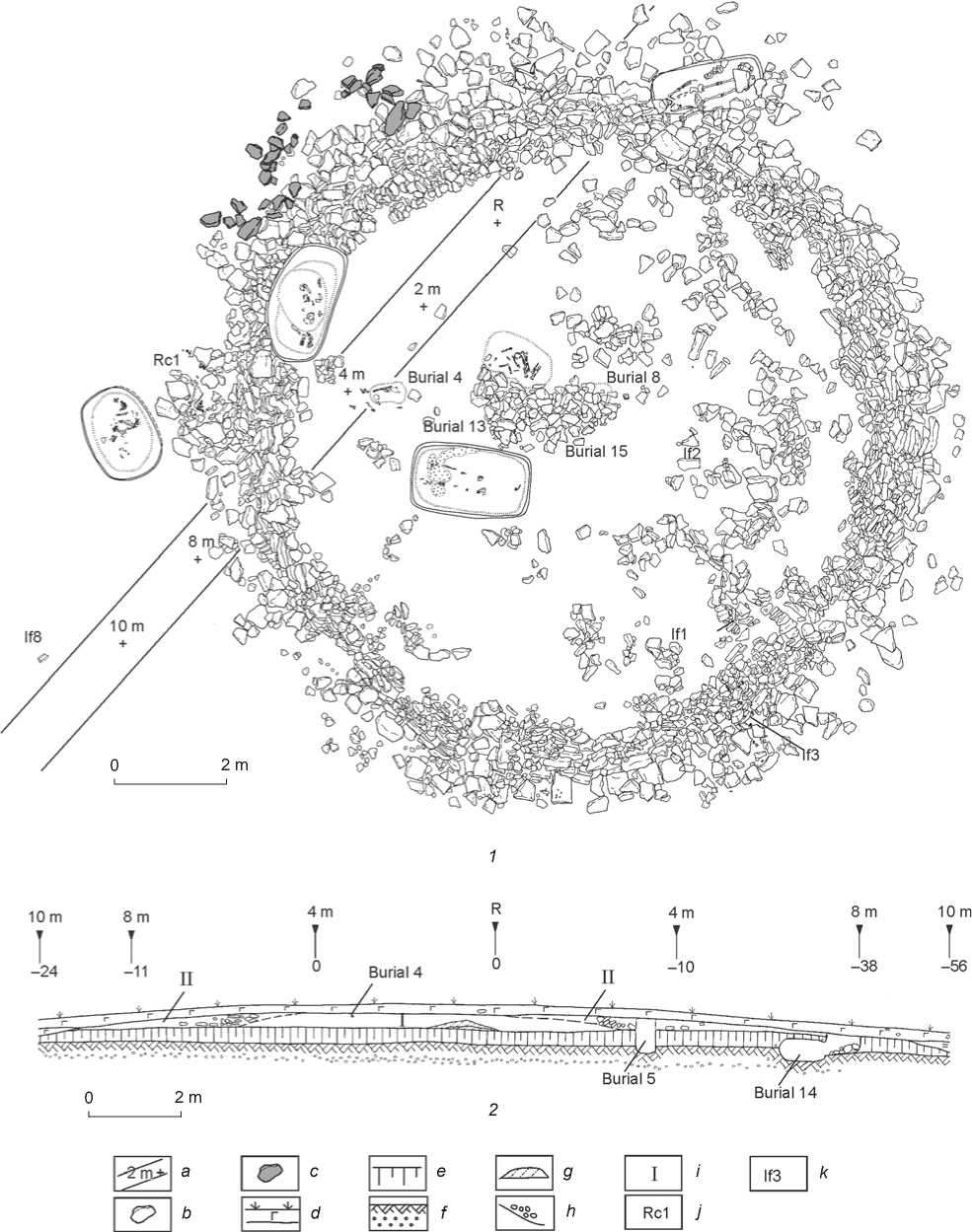

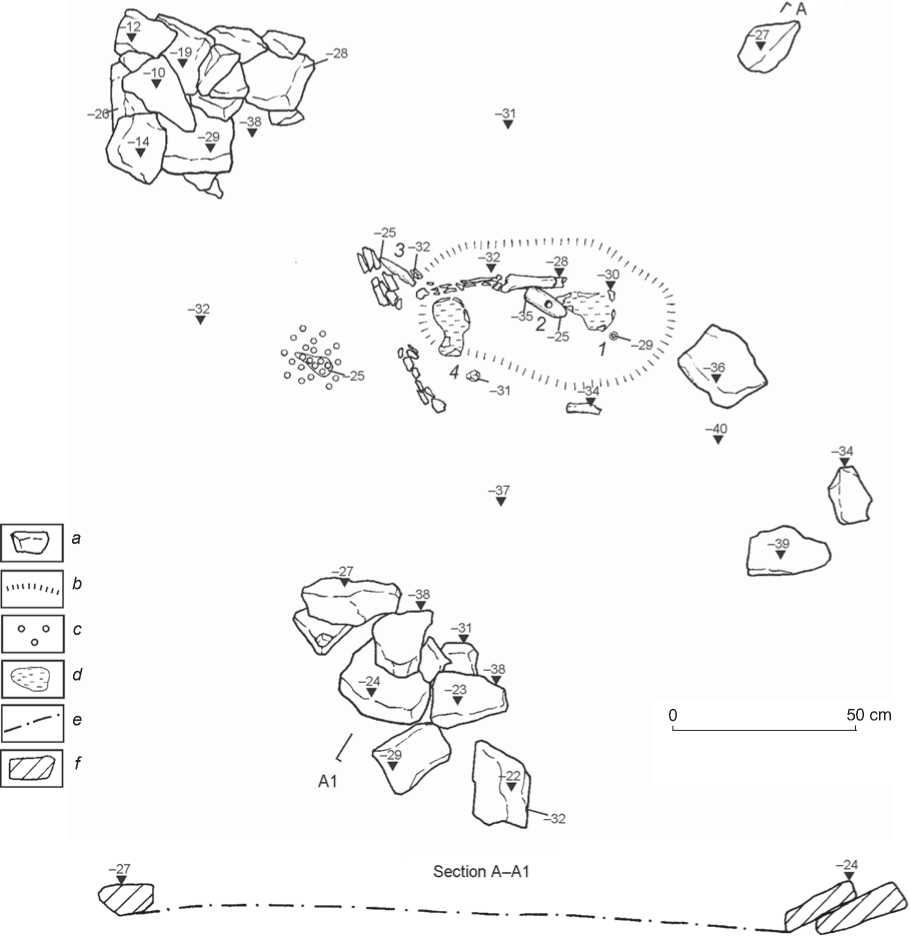

In 2011, A.A. Kalmykov excavated burial mound 1 (2014). Its height was 0.6 m; its diameter was 40 m. The aboveground part of the mound, which was badly damaged by plowing, consisted of two embankments and an underground structure, the cromlech-curb. Fifteen burials, 8 individual finds (IF), a ritual complex, and a complex with animal bones outside of the tomb were discovered in the mound. In addition, dozens of pottery fragments from at least five vessels were found. The vast majority of burials and finds are dated to various periods of the Bronze Age.

For identifying the stratigraphic features of the mound, one baulk oriented along the azimuth 42° 30’ due to the configuration of the land plot designated for the study, was left unearthed (Fig. 2). According to its “eastern” face, the buried soil in the center of the mound was located at a depth of –65 cm from the reference level (R). It could be seen in the form of a horizontal strip approximately between the levels of 10.7 m S and 10.4 m N, where it was cut by pits near the mound, which originated from taking the soil for the embankment. The spoil heap, evidently from burial 15, lay on the surface of the buried soil, at the section of 1.7 m S–0.1 m N.

Embankment I of lenticular cross-section was the earliest in the mound; it was located on top of the spoil heap and buried soil. The length of the embankment on its frontal face was slightly less than 10 m; the height was 0.4 m. The slopes of embankment I were covered by cromlech-curb. On one side of the baulk, it could be seen in the form of two groups of stones on both sides of the embankment. The lower stones were laid on the buried soil at the edge of the embankment. Each subsequent stone was laid on the underlying stone covering it not completely, but only partially, with a shift towards the center of the mound (following the principle of “dominoes”). The sides of the stones facing inside the ring rested on the earthen base of embankment I. The angle of inclination of the stones to the horizon reached 35–40°. The greatest number of stones in the cromlechcurb reached 11–12 rows.

Embankment II is of a later date. It covered the earlier part of the mound, and it is not clear which burial it was associated with (Fig. 2, 2 ).

In plan view, the cromlech-curb had a ring-like shape and completely surrounded embankment I. The stones were located on the slopes of this embankment and on the adjacent areas of the buried soil. The outer diameter of the stone structure was about 13.5–14.0 m. The width of the stonework (stone ring) in undamaged areas varied from 1.4 to 2.0 m (in a small area in the southwestern sector it was 1 m). The diameter of the space enclosed in

Fig. 1 . Location of the Levoyegorlyksky-3 cemetery.

the cromlech-curb was approximately 10 m. The greatest preserved height was 0.55 m (Fig. 2; 3, 1 ).

Broken stone and slabs of dense fine-grained sandstone of gray and gray-yellow color were mainly used for building the cromlech-curb. Their sizes vary from a length of 0.2–0.5 m to a size of 1.05 × 0.55 × 0.17 m. Several slabs in the southeastern sector were probably trimmed to acquire a subrectangular shape (Fig. 3, 2 , 3 ).

The double name of the stone structure underneath the embankment (cromlech-curb) originated from the double function performed by this structure. First, it was a stone ring surrounding the embankment (ritual purpose), and second, it was stonework strengthening the edges of the embankment (practical purpose).

Thus, the cromlech-curb of the mound reflected a special type of slab “megalithism” in the mound architecture of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya community. It had its own specific features as compared to the cromlechs of some Maikop mounds built mainly from piles of pebbles and stones. The carriers of the protoPit-Grave culture of the pre-Maikop period in the fifth millennium BC and the Pit-Grave culture of the northern Caucasus in the fourth millennium BC did not erect cromlechs around their mounds.

The remains of several stone structures located on the surface and inside the early embankment I, were unearthed inside the cromlech-curb. Some of them (in the center and in the eastern half of the space confined by the stone structure) were associated with burials 4, 7, 8, and 13

Fig. 2 . Map of the cromlech-curb of mound 1 ( 1 ), and the central part of the “eastern” side of the baulk ( 2 ).

a – baulk; b – stone; c – stones of the embankment; d – arable layer; e – buried soil; f – native soil with carbonates; g – spoil heap; h – stones on the side of the baulk; i – embankment and its number; j – ritual complex and its number; k – individual find and its number.

Fig. 3 . Cromlech-curb from mound 1.

1 – general view from the southeast after clearing; 2 – stonework in the cromlech-curb, view from the northeast; 3 – a part of the cromlech-curb with a trimmed slab, view from the south.

(see Fig. 2, 1 ). These burials showed deterioration to various degrees, but it is certain that none of them were made according to the canons of burial practices of the Maikop tribes.

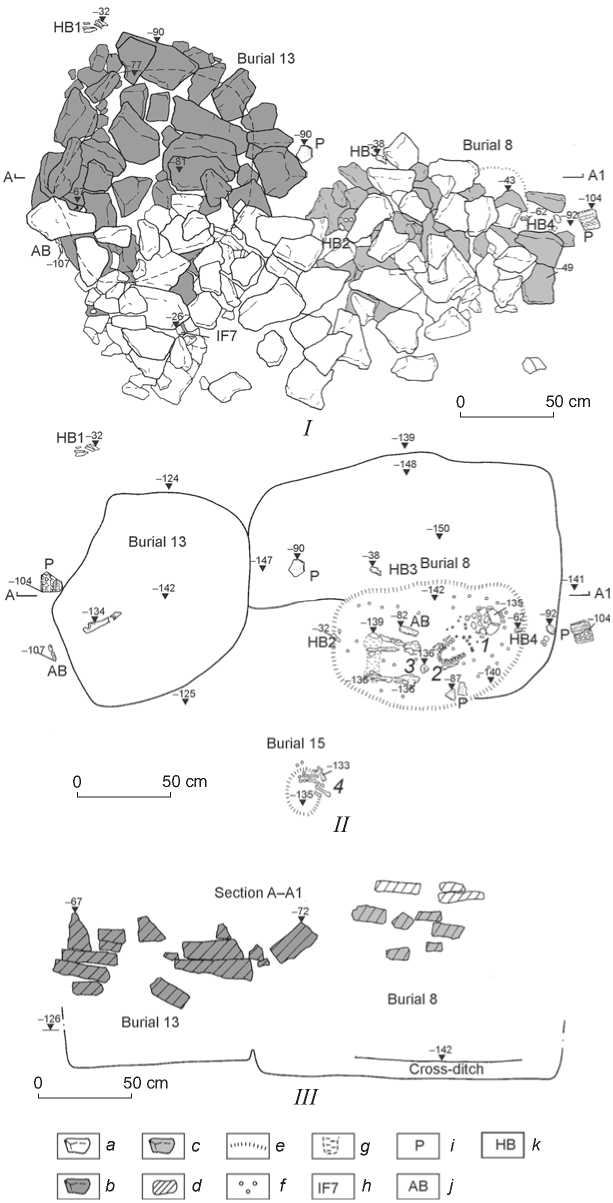

According to an entire range of features, the destroyed burial 15 was the main burial in the mound. Graves 4, 8, 13 were the earliest group of intrusive burials. Burial 13 was badly disturbed and yielded little information, thus this article will not consider that burial, although we should note a number of features which show similarities to burial 8 located nearby. Both burials were of approximately the same depth, had their own stone lids covered with joint piling of stones; both burials contained the ribs of large herbivores and pottery fragments from a single vessel (from burial 15).

Several finds dating back to the time when the burial mound was constructed, that is, to the MNC period, were made inside the cromlech-curb and in the embankment. The finds included a flint arrowhead found in the southeastern sector in the stone piling near the interior border of the cromlech-curb, in a hole among the stones. The arrowhead is made of semi-transparent flint of dirty-milky color; it is of subtriangular shape with a shallow notch in the base. Owing to the unevenness of the notch, the lower part of the object acquired a slightly asymmetric shape. The edge of the arrowhead was retouched along the entire perimeter. The length of the object is 3.3 cm, the greatest width is 2.0, the thickness is 0.5 cm, and the weight is 3.1 g (Fig. 4, 1). This type of arrowhead with a slight notch at the base occurs relatively rarely among the finds from the burial mounds of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya community. A similar object was found in mound 7 at the Abinsk cemetery belonging to the tribes of the Early Galyugay-Sereginskoye variant

3 cm

1 cm

3 cm

1ЛЕВ0ЕГ0РЛ.-3

|кУРГ. 1 онз'

Fig. 4 . Individual finds dating from the time of the origin and beginning of the mound’s functioning.

1 – flint arrowhead (IF1); 2 – fragment of pottery (IF2); 3 – rim of ceramic receptacle (IF8); 4 – fragments of pottery (IF3); 5 – photo of IF3 in situ , view from the east.

of the MNC, but there was no retouching along the edge (Korenevskiy, 2004: 178, fig. 48, 12 ). Treatment of the arrowhead edges with serrated retouch clearly reveals that it was the production of Maikop armorers or warrior-hunters of the pre-Caucasian Chalcolithic. In the pre-Maikop period, arrowheads as a rule were not treated in this manner, as is the case with the arrowheads from the Konstantinovka settlement on the Lower Don, which belonged to the steppe Eastern European Chalcolithic. The only exception is a large arrowhead with retouching along the edge from Meshoko (Stolyar, Formozov, 2009: 95, fig. 25, 4 ). The arrowhead from mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3 cemetery is smaller and lighter; it is clearly not associated with arrows for the heavy and large bows of the pre-Caucasian Chalcolithic and is better correlated with the small and quick-firing bows of the Maikop population.

Ocher sherds (fragments of the Maikop pottery) occurred in the ancient mound (Fig. 4, 2, 3). One of the sherds (IF8) found outside the cromlech-curb at a distance of 9.6 m to the west-southwest of the ancient center of the mound, is of particular interest. It is a rail-shaped rim remaining from a Maikop receptacle (Korenevskiy, 2004: 32, fig. 42, 12, 13). The size of the fragment is 14.0 × 5.8 cm; the width of the rim is 5.5; the reconstructed diameter of the vessel is about 93–94 cm. The volume of such a receptacle could reach 20–26 liters. Such vessels are typical of the Early Galyugay-Sereginskoye variant or the related Psekup variant (MNC), but they occur rarely in the mounds of the latter variant. Such receptacles are not typical of the pottery of the Novosvobodnaya group or the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC.

A crushed pottery vessel (IF3), consisting of 45 undecorated fragments of terracotta color, belongs to the MNC. It was discovered at a distance of 7.2 m to the south-southeast of the ancient center of the mound. The fragments were separated by a strip (1.8 × 0.8 m) across the entire stone ring of the cromlech-curb (see Fig. 2, 1 ; 4, 5 ). Such pottery was not found in other places of the mound and the cromlech-curb. The circumstances of the discovery of the fragments indicate that a ceramic vessel was deliberately broken in this place against the stones in the process of erecting the cromlech-curb. It was not possible to completely reconstruct the shape of the vessel. Its rim was straight, sharply bent outward, and rounded at the top. The reconstructed diameter of the rim is about 16– 17 cm; the height of the rim is over 3 cm (see Fig. 4, 4 ).

Ritual complex 1, discovered 5.5 m to the west of the ancient center of the mound, also belongs to the time when the cromlech-curb was constructed. It consisted of fragments of two or three ceramic vessels, and fragments of the lower jaw of a large animal, found among the stones of the cromlech-curb. The finds were concentrated in four clusters (see Fig. 2, 1 ). Typologically, the forms of that dishware are not reconstructible. The fragments are associated with hand-built pottery. One fragment is covered with a layer of carbon deposits from burning.

Burial 15 (the main burial) was located in the geometric center of the space bounded by the cromlechcurb (see Fig. 2, 1 ). It was associated with the removed

Fig. 5 . Covers of burials 8 and 13, and stone embankment on the top ( I ), plans of burials 8, 13, and 15 ( II ), and the cross-section of burial structures ( III ).

a – stone piling above the covers; b – stones of the cover of the burial 8; c – stones of the cover of the burial 13; d – cross-section of a stone; e – boundary of the bedding; f – ocher; g – bone ash; h – individual find and its number; i – fragment of pottery (from burial 15); j – animal bones; k – human bones (from burial 15).

1 – stone beads (19 spec.); 2 – bone composite necklace; 3 , 4 – flint flakes.

native soil found on one side of the baulk. The boundaries of the spoil heap in plan view could not be traced. The burial was almost completely destroyed (Fig. 5, II ), and two more burials (No. 8 and 13) were made in its crossditch. In addition, burial 15 was largely damaged as a result of the activities of large burrowing animals. Only a part of the bones of a human foot standing on its sole have been preserved from the burial in situ , as well as a flint flake lying on the foot. Ashes of dark brown color and ocher particles were found under the bones. Judging by the level of the buried soil and the remains of the burial, the reconstructed depth of the grave might have reached approximately 0.75 m. Obviously, the fragments of bones and teeth found in various places during the removal of the stone piling over burials 8 and 13 and during the clearing of their filling, were parts of the skeleton of the person from burial 15.

The fl int flake is a thin blade spall from a pebble. One edge is sharp and was used for cutting. The stone is semitransparent, brown in color. A weathering crust has survived on a small area. The size of the artifact is 3.7 × 2.2 × 0.4 cm (Fig. 6, 5 ).

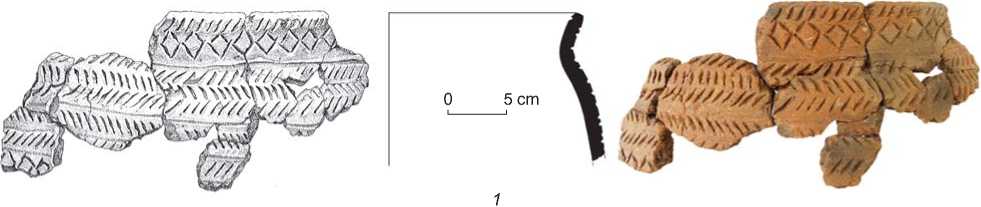

Fragments of a vessel have been found among the stones of the cover and in the filling of burials 8 and 13 (see Fig. 5, I , II ; 7, 2 ). The fragments of this vessel have not been discovered in other parts of the mound. Its shape could not be fully reconstructed, but it was a large thick-walled handmade pot of large diameter with steep shoulders and an outwardly bent rim flattened on the top. The vessel was made of dense clay dough with the addition of a large amount of gruss, chamotte, and fine quartz sand. The firing color is red-brown with extensive gray-brown spots on the external surface. The entire external side of the surviving part of the vessel and the upper edge of the inner side of the rim are covered with a sophisticated geometric pattern consisting of combinations of indented lines and slanting imprints of a nail-shaped stamp. The size of the reconstructed part is 12.8 cm in height including a 3.8 cm rim; the reconstructed diameter of the rim is approximately 32 cm. The thickness of the walls and rim is 1.3 cm (Fig. 7, 1 , 3 , 4 ).

This vessel is not associated with the MNC. The lush ornamental décor on the surface of the vessel, extending to the rim and the pre-rim part of the body, makes it possible to attribute the vessel to the objects of the steppe Eastern European cultures of the Early Copper-Bronze Age. Individual examples of such ornamentation can be found on the dishware of the steppe type, for example, on the first group from the Konstantinovka settlement (Kiyashko, 1994: 103–107). It is difficult to find more precise parallels because of the fragmentary nature of the vessel in question.

Burial 8 was found in the cross-ditch of the main burial 15. The shape, size, and boundaries of the grave structure cannot be traced. Only a stone cover and the level of the bottom marked by decay from the bedding, were found from the original burial (see Fig. 5).

The stone cover was a piling of slabs (predominantly) and stones, loosely laid side by side in three to four layers. At the top level, the piling stretched along the west-east line and had a suboval shape measuring approximately 1.3 × 0.9 m. Slabs and stones which constituted the cover showed no traces of processing. They included several slabs of dense white limestone, the latter not being found in the cromlech-curb. The size of the largest slab was 37 × 24 × 11 cm.

During the clearing of the cover and the subsequent removal of soil before discovering the skeleton within the supposed boundaries of the burial, three times there were found fragments of human bones (from the skeleton from the main burial 15), a rib of a large herbivore animal, and several fragments of the above-described ceramic vessel.

The bottom of burial 8 was located about 0.5 m below the base of the stones of the cover; it can be observed from decay remaining from the two-layered bedding. Unstructured decaying of red-brown color lay on top of the lower layer which, judging by the imprint on the ground, was a mat of coarse weaving. The bedding was strewn with ocher, most intensely behind the skull of the deceased.

A skeleton of a teenager in an unsatisfactory state of preservation was unearthed on the bedding. His skull was crushed; only bone ash and imprints of the long bones of the legs, pelvis, and fragmentary humerus bones have survived from the postcranial skeleton. Judging by them, the deceased was buried in a flexed supine position, with his head towards the east. His legs were extremely bent at the knee and hip joints and laid on the abdomen. The shoulder bones were directed towards the pelvis. It can be assumed that his hands were joined together.

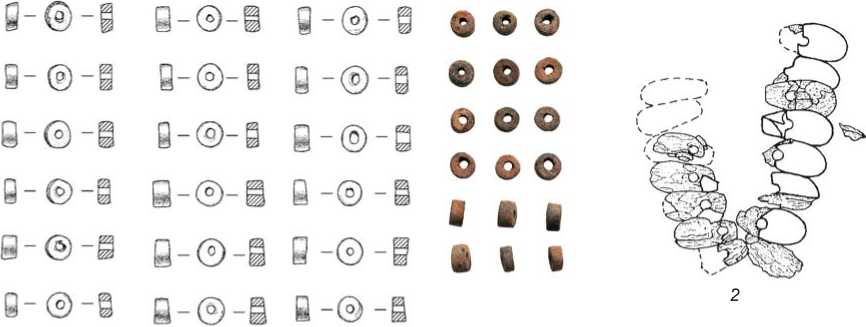

Stone beads were found in the area of the anatomical position of the neck and chest of the buried; a necklace of bone pendants was discovered in the chest region, and a flint flake lying flat, with the side with the undamaged weathering crust up, was lying near the left knee joint on the bedding. Most of the beads were located near the neck, in one line at an irregular distance from each other. Six beads were outside this group, near the chest; they lay flat at an identical, short distance from each other, forming a short (about 8 cm) straight line connecting the ends of a necklace of bone pendants. Probably, this group of beads and pendants were the decoration of some breastplate, the woven or leather base of which has not survived (see Fig. 6, 2 ).

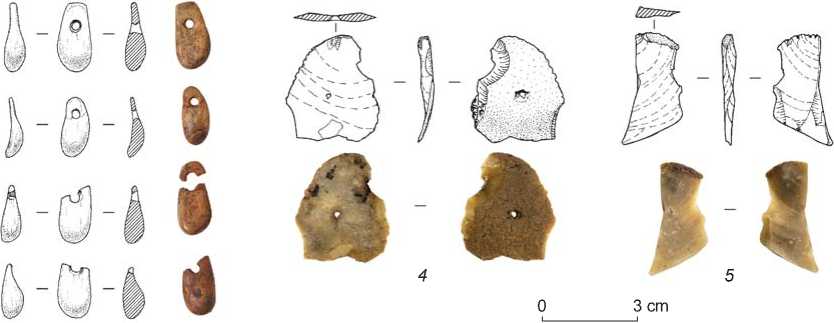

The beads are made of a solid black mineral. In total, there are 19 of them. The beads have the shape of a short cylinder with a transverse through hole. Their length is 0.35–0.55 cm; their diameter is approximately 0.8 cm; the diameter of the holes is 0.2–0.3 cm (see Fig. 6, 1 ). Beads of such shape made of stone, mother-

Fig. 6 . Grave goods from burials 8 ( 1–4 ) and 15 ( 5 ).

1 – stone beads; 2 – composite necklace in situ ; 3 – bone pendants from the necklace; 4 , 5 – flint flakes.

Fig. 7 . Ceramic vessel from burial 15, assembled from the fragments found in burials 8 and 13.

1 – restored part of the vessel; 2 – fragment in the filling of burial 8; 3 – ornamental décor on the outer surface of the vessel; 4 – ornamental décor along the upper edge of the inner side of the rim.

of-pearl, and paste are known among the tribes of the pre-Maikop period of the northern Caucasus, and among the carriers of the Maikop culture as an attribute of a particularly prestigious burial outfit. However, a special analysis of this category of items has not yet been carried out.

The composite necklace consisted of at least 16 bone pendants of the same type. They all are drop-shaped with a flattened narrowed upper part, in which a through hole for hanging or sewing was made. In their shape, the pendants clearly imitate deer teeth. A fully preserved pendant has a length of 2.1 cm, a maximum width of 1.1 cm, a maximum thickness of 0.7 cm, with the diameter of the hole 0.25 cm. The sizes of the other pendants are about the same or smaller (see Fig. 6, 2, 3).

Pendants in the form of deer teeth are not typical of the burial outfit used by the MNC tribes, and occur in its assemblages as rare exceptions. For example, they were found in burial 5 of mound 51 at the Klady cemetery (Rezepkin, 2012: 250, fig. 111, IV, 2 ). Adornments that have the shape of deer teeth began to appear as prestigious objects long before the MNC period. Thus, they are

Fig. 8 . Plan and cross-section of burial 4.

a – stone; b – boundary of the bedding; c – ocher; d – bone ash; e – reconstructed boundary of the bottom of the grave structure; f – cross-section of stone.

1 – gold pendant; 2 – stone beak-shaped hammer; 3 – bronze dagger; 4 – flint flake.

Fig. 9 . Burial 4 after clearing.

1 – general view from the southeast; 2 – skeleton and grave goods, view from the south.

known from the assemblages of the Nalchik burial ground (Kruglov, Podgaetsky, 1941: 74, fig. 8, 5 ; p. 91, fig. 28, 2 ).

The flint flake is a very thin blade spall from a pebble. One side is completely covered with weathering crust. The stone is semi-transparent, of brown color. A small through hole of natural origin with a diameter of approximately 1 mm is in the center. The size of the object is 3.3 × 2.8 × × 0.4 cm (see Fig. 6, 4 ).

Burial 4 was made in embankment I, 2.6 m to the west of the ancient center of the mound (see Fig. 2, 1 ). The grave has survived in a fragmentary state (Fig. 8; 9, 1 ). The upper part of the burial structure and most of the skeleton were destroyed by plowing. Earthen details of the burial structure could not be identified. The bottom of the burial, marked by decay of the bedding, as well as a level of finds and bones, was in the middle of embankment I. Its northwestern corner, composed of several sandstone stones of medium size (ca 25 × 15 × 8 cm), was more fully preserved. It had a clear rectangular shape externally. A cluster of stones to the south of the skeleton and four stones lying along the north-south line to the east of the skeleton could have been related to the structure of the grave. All of the stones were similar to the stones of the cromlech-curb.

The skeleton was in an unsatisfactory state. Most of the bones were missing; the available bones (right hand, a fragment of the left humerus, proximal parts of the femoral bones) were crushed into small fragments. Only bone debris has remained from the skull and pelvis. However, the posture of the buried person can be reconstructed definitively on the basis of the remains: he lay in a flexed supine position, with his head towards the east. His arms were placed along his trunk; his right arm was straightened; his wrist was near his right hip joint. His legs were bent at the hip joints at an angle slightly more than a right angle, and turned with their knees to the right. The destroyed ends of the femoral bones were elevated (see Fig. 8; 9, 2).

Very thin bedding in the form of unstructured decaying of dark brown color could be seen under the bones. A disintegrated chunk of ocher was found in the area where hypothetically the feet of the deceased were located.

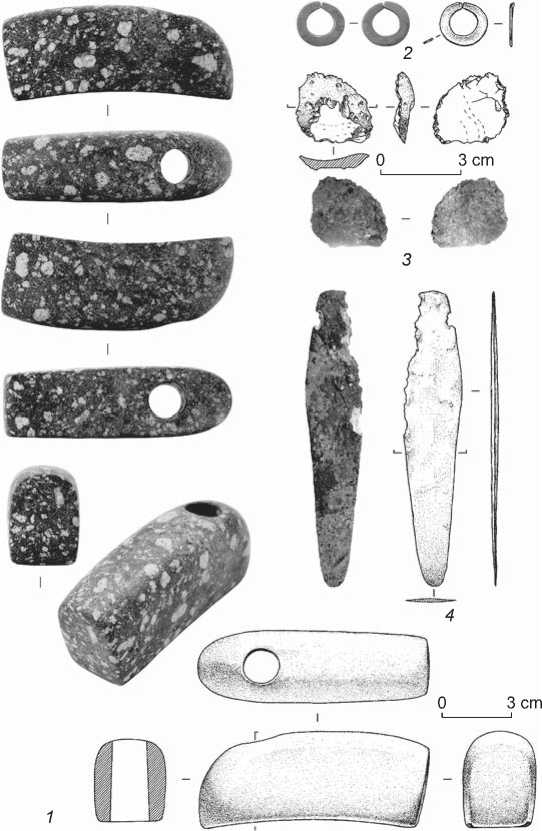

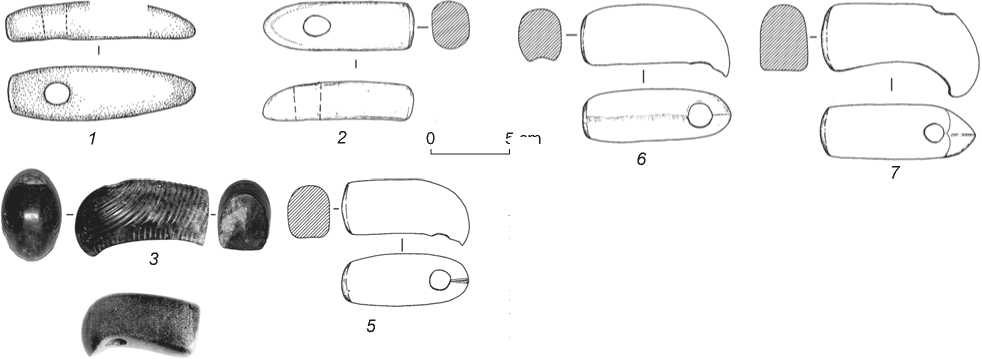

The grave goods included a gold ring-pendant of the headdress, stone beak-shaped hammer, bronze dagger, and a flint flake (Fig. 10).

A gold pendant was found near the southern boundary of bone ash, in the place of the anatomical position of the skull. The adornment was made in the form of a wide ring of thick hammered wire. The ends are closed. The size of the pendant is 1.7 × 1.6 cm with a thickness of 0.1 cm, and a weight of 1.9 g (Fig. 10, 2 ). Gold single looped rings are typical adornments in the elite burials of the MNC. They were chiefly made of wire and were not hammered (Korenevskiy, 2011).

A beak-shaped hammer was located between the right arm and the body of the buried. The end with the hole was raised and directed to the southwest (see Fig. 9, 2 ; 10, 1 ). The hammer has the form of a parallelepiped with a through hole shifted toward one of the ends (the butt). The butt is beak-shaped and slightly curved downward. The upper edges of the tool are smoothened. The striking part is flat. The hole from the drill is onesided and is slightly tapered towards the top. Its surface is smooth. The hammer is made of dense volcanic rock of gray-green color with white inclusions of various sizes. Most likely, it is serpentinite. The surface of the tool is polished. The total length of the object is 12.3 cm; the size of the cross-section in the middle part is 4.7 × 3.8 cm; the diameter of the hole ranges from 1.8 to 2.0 cm (see Fig. 10, 1 ).

Fig. 10 . Grave goods from burial 4.

1 – stone beak-shaped hammer; 2 – gold pendant; 3 – flint flake; 4 – bronze dagger.

Parallels of the beak-shaped hammer from burial 4 are well known. One object is an accidental find from the mounds near Pyatigorsk (Fig. 11, 2 ). Other objects are associated with the central piedmont of northern Caucasus, with the assemblages of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC. Locations of these finds are: Chegem I, mound 1, burial 8 (the hammer lay at the right shoulder of the deceased; an asymmetrical arrowhead was found at the same place) (Fig. 11, 7 ), mound 5, burial 2 (Fig. 11, 6 ); Chegem II, mound 27, burial 1 (Fig. 11, 5 ) (Betrozov, Nagoev, 1984: 9, 10, 28); and Maryinskaya-3, mound 1, burial 18 (Fig. 11, 3 ). In the latter assemblage, a beak-shaped hammer made of black stone lay at the right shoulder along with a bronze adze and bronze dagger. Radiocarbon dates for the wood from that burial gave the intervals of 3416–3364 and 3440–3020 BC. The averaging dendrochronological date is 3350 BC, that is, the 34th century BC (Kantorovich, Maslov, 2009: 115). Outside the MNC, such beakshaped hammers have been found in burial 1 of mound 1 in the village of Konstantinovka of the Zaporozhye Region (Ukraine) (Fig. 11, 1 ) and in burial 19 of mound 1 near the village of Stepan Razin in the Volga region (Fig. 11, 4 ) (Korenevskiy, 2013; Merpert, 1974: Fig. 10, 5 ; Markovin, 1976).

Beak-shaped hammers from the assemblages of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC are made of brown or black rock, not of serpentinite. Therefore, the serpentinite find from burial 4 of mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3 is in some way unique. In terms of the origin of the rock, it is most likely associated with the central part of the northern Caucasus, where various outcrops of

5 cm

Fig. 11 . Beak-shaped hammers of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC and their parallels in Eastern Europe (after: (Korenevskiy, 2013; Kantorovich, Maslov, 2009; Betrozov, Nagoev, 1984)).

1 – the village of Konstantinovka, mound 1, burial 1 (Melitopolsky District, Zaporozhye Region, Ukraine); 2 – Pyatigorsk, discovery from the mounds; 3 – Maryinskaya-3, mound 1, burial 18 (Stavropol Territory); 4 – village of Stepan Razin, mound 1, burial 19 (Volgograd Region); 5 – Chegem II, mound 27, burial 1; 6 – Chegem I, mound 5, burial 2;

7 – Chegem I, mound 1, burial 8 (the Kabardino-Balkar Republic).

serpentinite (weathering crusts of ancient ultrabasic rocks) occur within the Malkinskoye iron ore field (Kalganov, 1946: 167–168). In the burials of the Dolinskoye variant, the beak-shaped hammers lay near the humerus or thoracic bones of the deceased, exactly as in the burial under consideration.

A dagger on a copper base was at the right hip joint. Like the hammer, it was located in an inclined position. The raised point was directed to the northwest. The object belongs to the so-called Early Maikop type of tangless daggers. The blade is two-edged, tapering towards the rounded end. The handle is trapezoidal. A weakly expressed longitudinal rib is in the center of the dagger. The length of the object is 12.7 cm including a blade of approximately 9 cm; the maximum width (reconstructed) is 2.7 cm, and the maximum thickness is 0.25 cm (see Fig. 10, 4 ).

The shape of the Levoyegorlyksky dagger fits well with the Early Maikop type of the Galyugay-Sereginskoye and Psekup variants of the MNC. In the Caucasus, it appeared at the beginning of the fourth millennium BC. The dates of several examples of such weapons are known, including a dagger from burial 33 of mound 1 at the Maryinskaya-5 group, from the 38th–37th century BC (3767–3660 BC) (Kantorovich, Maslov, Petrenko, 2013: 92), from burial 13 of mound 14 at the Mandzhikiny cemetery, dated to the 38th–37th century BC (3781– 3693 BC), and from burial 3 of mound 1 at the Kudakhurt cemetery, dated to the 36th–35th century BC (3520– 3400 BC) (Korenevskiy, 2011: 26–28). A tangless dagger is a part of the assemblage from the Maikop burial mound, which can be dated by the date of burial 70 of mound 1 at the Zamankul cemetery to the 37th–36th century BC (3640–3500 BC) (Ibid.).

Stratigraphically, the daggers of the tangless type have twice shown an earlier position in the mounds in comparison with tanged daggers. A.A. Iessen was the first who pointed this out using the example of the primary and intrusive burials of the Maikop mound (1950). The same situation is confirmed by the stratigraphy of mound 1 at the Maryinskaya-5 burial ground. Dates of burials 12 and 25 there with tanged daggers were in the range of the 34th–32nd centuries BC (Kantorovich, Maslov, Petrenko, 2013: 93).

A flint flake lay flat next to the left hip joint, beyond the boundaries of the remaining section of the bedding. It is a piece of pebble with numerous removals. The flint is brown and semitransparent (see Fig. 10, 3 ).

Inclusion of a flint flake into the grave goods apparently had a certain stable meaning for the people who left this burial, since such cases have been recorded many times. For example, flint flakes were found in the two burials described above.

General observations

Mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3 was made on an important communication route between the central piedmont of the northern Caucasus and the Kuma-Manych Depression, which is the valley of the Yegorlyk River. Burial 15 was the main burial in the mound. Proceeding from logic, as well as stratigraphic observations, the discharge of ancient soil to the surface is associated with precisely that early burial. Presumably, the place of the burial soon (otherwise, the spoil heap would have been washed away by rainwater) was covered by a small earthen embankment 11–12 m in diameter, the slopes of which were strengthened with a cromlech-curb.

In accordance with the burial rite, fragments of Maikop pottery and an arrowhead ended up in the cromlech-curb. The arrowhead is not an isolated example of such a discovery in a MNC mound. Thus, an arrowhead was found in the embankment over the Maikop burials of the Bolshoy Ipatovskiy mound (Korenevskiy, Belinsky, Kalmykov, 2007: 214, fig. 74, 8 ). This may reflect a ritual shot into the embankment of a mound from a fast-firing bow, since arrowheads weighing 3 g with jagged edges belong to the weaponry of that type.

Judging by the pottery fragments and the position of the surviving bones, the main burial 15 is not related to the complexes of the “Maikop mound circle” and is obviously associated with the local tribes of the Pit-Grave cultural community. However, the people who left it clearly adhered to some of the elements typical of the MNC burial traditions, and while erecting the first mound they used first class pottery of the Maikop culture, including the fragments of huge receptacles. Such pottery primarily occurred in the Early Galyugay-Sereginskoye variant of the MNC (Korenevskiy, 2004: 50–53).

Burials 4, 8, and 13 were further made inside of the cromlech-curb. Judging by the position of the buried persons, all the burials belong to the Pit-Grave culture, and do not contain MNC pottery. On the whole, the presented materials suggest that the center of the mound was founded and functioned as a burial place for the members of one or more clans of the carriers of the PitGrave culture. The commonness of their burial rites is emphasized by the inclusion of small fragments of flint into their grave goods with some symbolic meaning, since practical use of such small flakes as tools is quite doubtful. Despite strong deterioration of the skeletons in the graves under consideration, it can be stated that the deceased of various ages found their place of repose in the burial mound.

Burial 4 contained grave goods that make it possible to view the burial as an elite grave with the military symbols of the Early Maikop or Psekup variant of the MNC, that is, a syncretistic burial of the Pit-Grave-Maikop type. At the same time, the burial contained a beak-like hammer typical of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC in the central part of the northern Caucasus, belonging to its late stage (Ibid.: 54–57), when tanged daggers were typical. All this makes the complex under consideration unique evidence of mutual occurrence of things from the early and late stages of the MNC. Such cases are very rare. One of them is the burial of the Inozemtsevo mound, which was investigated in 1976. That mound contained a bowl of the Galyugay-Sereginskoye type and pottery of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC with a typical set of bronze objects (Korenevskiy, Petrenko, 1982). This complex can be dated to the 35th–34th century BC (3499– 3349 BC) (Korenevskiy, 2011: 29).

The dates of tangless daggers in the central piedmont of the northern Caucasus are associated mainly with the range of 38/37th–36/35th centuries BC. Thus, burial 4 can be dated to at least the late first half to the middle of the fourth millennium BC. Such weapons are unknown in the second half of the fourth millennium, in the interval of 3400–3000/2900 BC. The pottery of the Early Maikop type, discovered in the cromlech-curb of the mound, does not contradict such dating.

The beak-shaped hammer is a very interesting type of object belonging to the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC, since they have a very mysterious configuration and origin. Their parallels made of bone and stone in the south of Eastern Europe have been analyzed earlier (Rezepkin, 2000: 29, Abb. 9; Korenevskiy, 2013: 21, fig. 5). The general conclusion was that stone beak-shaped hammers appeared as an imitation of bone beak-like pickaxes of the Pit-Grave culture (Rezepkin, 2000: 29), moreover, as the development of the shape of the horn pickaxe, a weapon and tool of the Chalcolithic, of the pre-Maikop period (Korenevskiy, 2013). In the case of burial 4, different solutions can be given to the problem of who influenced the emergence of such an object, in the context of a burial rite according to the canons of the Pit-Grave culture.

The first answer is that the tribes of the Dolinskoye variant of the MNC, among the materials of whom beak-shaped hammers have been repeatedly found, exerted influence on the carriers of the Pit-Grave culture. However, such a solution finds serious challenges in the chronology of the assemblages. In burial 4 of mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3, a beak-shaped hammer was found in association with an object of the Early Maikop period of the MNC, a tangless dagger. In the assemblages of the Dolinskoye variant, beak-shaped hammers were associated with tanged daggers and belong to the late stage of MNC.

Another answer to the question is that beak-shaped hammers appeared in the northern Caucasus among the carriers of the Pit-Grave culture as the development of their bone prototypes in the Final Early MNC and were subsequently adopted by the Dolinskoye tribes of the

MNC. Such a course of events has additional supporting arguments. The first of these arguments is related to the location of beak-shaped hammers in the burials of the Dolinskoye variant at the shoulder and chest, that is, “at the hand” of the buried person. This reflects not the Maikop, the so-called “abstract tool” tradition of placing a prestigious tool in a burial in a corner or under the wall of the grave, but the Chalcolithic “specific tool” tradition of the proto-Pit-Grave and Pit-Grave cultural communities: near the shoulder, chest, or elbow of the deceased, who lay in a flexed supine or extended position.

A beak-shaped hammer in burial 4 of mound 1 at Levoyegorlyksky-3 cemetery was located precisely in the same way, at the elbow. This version seems to be more justified.

Burial 8 (of a teenager) in mound 1 also contained prestigious personal adornments of clothing of the time, which not so commonly occurred in the burials of the Maikop tribes, such as a necklace made of pendants in the form of deer teeth.

Conclusions

The materials discussed above make it possible to speak about a strong influence of cultic practices and values of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya cultural community on their northern neighbors (carriers of the Pit-Grave culture) in terms of organizing burial space, constructing cromlechs and curbs, and using broken pottery for building the burial mound. The materials show that prestigious valuable objects of the Maikop military elite, such as tangless daggers, also became the objects of military prestige for the nobility of the carriers of the Pit-Grave culture. At the same time, stone beak-shaped hammers appeared in the set of prestigious objects among the tribes of the Pit-Grave cultural community. This object, which might have had a cultic purpose, was borrowed by the Dolinskoye tribes from the earlier cultural context of the Early Pit-Grave or Early Maikop population. It is difficult to identify the source of the borrowing with more precision because of the scarcity of sources.