Pre-Sauromatian Burials in the Lower Volga Region According to Archaeological and Paleopathological Data

Автор: Dyachenko A.N., Pererva E.V.

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: Древний мир и археология

Статья в выпуске: 5 т.30, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Introduction. The time period between the 9th and the 7th centuries BC in the Volga-Ural and the Lower Volga regions is commonly referred to in scholarly literature as the “Pre-Sauromatian period.” This article analyzes previously unpublished archaeological and paleoanthropological materials from five pre-Sauromatian burial mounds: Solodovka I (2 burials), Lenin II, Tingutinsky (Volgograd region), and the single kurgan Evdyk (Republic of Kalmykia). Four of the five burial complexes presented here have not been published before. Methods and materials. Due to the poor preservation of the paleoanthropological material, the study employed a standard protocol for assessing the occurrence of pathological conditions in the bones of the postcranial skeleton and skull. Analysis and discussion. The burials examined in this publication, originating from the Lower Volga region, date back to the 8th – early 7th century BC. The most characteristic feature of the archaeological complexes of this period in the Lower Volga region is the “impoverishment” of the material artifacts. Conclusions. Pre-Sauromatian burials are most often secondary insertions. The grave pits are predominantly rectangular in shape. The deceased individuals are typically placed in a flexed or semi-flexed position on their side with their heads oriented eastward or westward. The burials are usually accompanied by animal remains and characteristic ceramic vessels, while metal objects are relatively rare. The study of pathological features in individuals from the pre-Sauromatian burials in the Lower Volga region suggests that the diet of this population was dominated by tough and hard foods rich in animal protein. Traumas and markers of intense physical activity indicate some degree of social tension within the community, likely related to competition for resources under changing conditions. Signs of episodic and specific stress suggest that the population experienced stress during childhood. Indicators of negative environmental (vascular reactions) and social influences (traumas, arthrosis, and spinal diseases) allow us to hypothesize that nomadic communities of the 9th – 7th centuries BC were highly mobile. Authors’ contribution. A.N. Dyachenko analyzed the archaeological material examined in this study. E.V. Pererva analyzed the anthropological material from pre-Sauromatian burials. Funding. The study was funded by the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 25-68-00011 “Tempora incognita in the history of the Volga-Ural region: culturalhistorical, anthropological paleoecological prerequisites and consequences of the change of eras and cultures at the turn of the Late Bronze Age – at the beginning of the Early Iron Age”, https://rscf.ru/project/25-68-00011/.

Archaeology, Pre-Sauromatian period, nomadic communities, Early Iron Age, paleopathology, traumas

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149149826

IDR: 149149826 | УДК: 903’1(470.4) | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2025.5.2

Текст научной статьи Pre-Sauromatian Burials in the Lower Volga Region According to Archaeological and Paleopathological Data

ДРЕВНИЙ МИР И АРХЕОЛОГИЯ

DOI:

Abstract. Introduction. The time period between the 9th and the 7th centuries BC in the Volga-Ural and the Lower Volga regions is commonly referred to in scholarly literature as the “Pre-Sauromatian period.” This article analyzes previously unpublished archaeological and paleoanthropological materials from five pre-Sauromatian burial mounds: Solodovka I (2 burials), Lenin II, Tingutinsky (Volgograd region), and the single kurgan Evdyk (Republic of Kalmykia). Four of the five burial complexes presented here have not been published before. Methods and materials. Due to the poor preservation of the paleoanthropological material, the study employed a standard protocol for assessing the occurrence of pathological conditions in the bones of the postcranial skeleton and skull. Analysis and discussion. The burials examined in this publication, originating from the Lower Volga region, date back to the 8th – early 7th century BC. The most characteristic feature of the archaeological complexes of this period in the Lower Volga region is the “impoverishment” of the material artifacts. Conclusions. Pre-Sauromatian burials are most often secondary insertions. The grave pits are predominantly rectangular in shape. The deceased individuals are typically placed in a flexed or semi-flexed position on their side with their heads oriented eastward or westward. The burials are usually accompanied by animal remains and characteristic ceramic vessels, while metal objects are relatively rare. The study of pathological features in individuals from the pre-Sauromatian burials in the Lower Volga region suggests that the diet of this population was dominated by tough and hard foods rich in animal protein. Traumas and markers of intense physical activity indicate some degree of social tension within the community, likely related to competition for resources under changing conditions. Signs of episodic and specific stress suggest that the population experienced stress during childhood. Indicators of negative environmental (vascular reactions) and social influences (traumas, arthrosis, and spinal diseases) allow us to hypothesize that nomadic communities of the 9th – 7th centuries BC were highly mobile. Authors’ contribution. A.N. Dyachenko analyzed the archaeological material examined in this study. E.V. Pererva analyzed the anthropological material from pre-Sauromatian burials. Funding. The study was funded by the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 25-68-00011 “Tempora incognita in the history of the Volga-Ural region: culturalhistorical, anthropological paleoecological prerequisites and consequences of the change of eras and cultures at the turn of the Late Bronze Age – at the beginning of the Early Iron Age”,

Citation. Dyachenko A.N., Pererva E.V. Pre-Sauromatian Burials in the Lower Volga Region According to Archaeological and Paleopathological Data. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 4. Istoriya. Regionovedenie. Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya [Science Journal of Volgograd State University. History. Area Studies. International Relations], 2025, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 15-33. DOI:

Аннотация. Введение. Временной отрезок с IX по VII в. до н. э. для территории Волго-Уралья и Нижнего Поволжья в научной литературе принято именовать как «предсавроматский период». В предлагаемой статье анализируются ранее не опубликованные археологические и палеоантропологические материалы из пяти подкурганных захоронений предсавроматского времени: Солодовка I (2 погребения), Ленина II, Тингутин-ский (Волгоградская область) и одиночный курган Эвдык (Республика Калмыкия). Материалы и методы. Из-за неудовлетворительной сохранности палеоантропологического материала в процессе исследования использовалась стандартная программа оценки встречаемости патологических состояний на костях посткраниального скелета и черепа. Анализ и дискуссия. Дата рассмотренных в данной публикации погребений, происходящих с территории Нижнего Поволжья, – VIII – первая половина VII в. до н. э. Наиболее характерной чертой археологических комплексов вышеуказанного периода на территории Нижнего Поволжья является «обедненность» вещевого материала. Заключение. Погребения предсавроматского времени чаще всего впускные. Могильные ямы в основном имеют округлую форму. Погребенный в них человек преимущественно располагается скорченно на боку головой на восток. В захоронениях встречаются останки животных, разнообразная керамика, а металлические изделия крайне редки. Изучение патологических особенностей индивидов из погребений предсавроматского времени Нижневолжского региона позволяет предположить, что у населения в диете преобладали вязкие и твердые продукты, богатые животным белком. Травмы и маркеры интенсивной физической активности указывают на некоторое социальное напряжение в обществе, связанное с борьбой за ресурсы в новых условиях. Признаки эпизодического и специфического стресса свидетельствуют о том, что население этого периода испытывало стресс в детстве. Индикаторы негативного воздействия окружающей (васкулярная реакция) и социальной среды (травмы, артрозы и болезни позвоночника) позволяют предположить, что сообщества кочевников IX–VII вв. до н. э. отличались высокой степенью мобильности. Вклад авторов. А.Н. Дьяченко провел анализ археологического материала, который исследован в работе. Е.В. Перерва проанализировал антропологический материал, происходящий из погребений предсавроматского времени. Финансирование. Исследование выполнено за счет гранта Российского научного фонда № 25-68-00011 «Tempora incognita в истории Волго-Уральского региона: культурно-исторические, антропологические, палеоэкологические предпосылки и последствия смены эпох и культур на рубеже поздней бронзы – в начале раннего железного века»,

Цитирование. Дьяченко А. Н., Перерва Е. В. Погребения предсавроматского времени на территории Нижнего Поволжья по данным археологии и палеопатологии // Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 4, История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения. – 2025. – Т. 30, № 5. – С. 15–33. – (На англ. яз.). – DOI:

Introduction. The beginning of the 1 st millennium BC marked the advent of a new era in the history of the Eurasian steppes, defined primarily by the transition of its inhabitants into the Early Iron Age and the establishment of a nomadic pastoral economy (“nomadism”), the earliest manifestations of which had already emerged by the end of the Late Bronze Age. The period from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC in the Northern Black Sea region, the steppe foreland of the Caucasus, and the Lower Don region is commonly referred to in scholarly literature as the “pre-Scythian period,” “pre-Scythian era,” or “Cimmerian era.” In contrast, for the Volga-Ural and the Lower Volga regions, the term “pre-Sauromatian period” is more frequently used, denoting the epoch preceding the appearance of the historical Sauromatians in the 6th century BC [33, p. 240; 35, p. 84].

The archaeological sites of the southern Russian steppes from the 9th – 7th centuries BC are typically associated with the Chernogorovka and Novocherkassk archaeological cultures [41, p. 55; 24, p. 129; 31, pp. 6-19; 11, p. 43]. Although issues of cultural genesis, periodization, and chronology of pre-Scythian archaeological cultures have received considerable attention in Russian historiography in recent decades [38; 16; 19; 31, among others], questions regarding the ethnic attribution of these sites, as well as the chronological and spatial relationship between the Chernogorovka and Novocherkassk cultural lineages, remain unresolved.

For the Lower Volga region, these issues are further complicated by the relatively small number of burial sites from the 9th – 7th centuries BC, their sparse distribution, and the small number of available absolute dates. At the same time, the discovery of new pre-Scythian (pre-Sauromatian) archaeological sites in the region in recent decades has shown some progress. Most of these materials have been published and assigned cultural-chronological characteristics within the broader context of synchronous Eurasian steppe antiquities [10; 22; 33; 25; 31; 17; 36; 6].

There has also been progress in the study of the anthropological aspects of pre-Sauromatian sites. In this regard, the works by M.A. Balabanova are particularly noteworthy, as the author has examined paleoanthropological materials from kurgan cemeteries in the Lower Volga and Lower Don regions. Based on craniological analysis, the researcher characterized the intragroup structure of the 11th – 7th centuries BC population as heterogeneous, suggesting that the pre-Sauromatian craniotype was formed from several components. According to M.A. Balabanova, the primary bearers of this morphological complex (a mesocranial cranium with a broad, slightly flattened upper face and a sharply protruding nose) were representatives of the Srubnaya cultural-historical community and ethnic groups that migrated to the Lower Volga region from Central Asia at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC [4, pp. 167-168]. Later, M.A. Balabanova proposed that various ethnic groups and tribal unions contributed to the formation of the pre-Scythian population in the Lower Volga region [5, p. 16].

It is important to note the closely related works by E.V. Pererva, which analyze the paleopathological characteristics of the nomads from 9th – 7th century BC burials [28; 29]. The author concludes that the pre-Sauromatian population exhibited a distinctive steppe pathological complex, manifested through low frequencies of caries, abscesses, signs of inflammatory processes and infections, as well as markers of diseases associated with micronutrient deficiencies in adults. At the same time, individuals from the 9th – 7th centuries BC showed high rates of dental calculus, periodontal disease, vascular reactions in bone tissue resembling “orange peel” texture, and enamel hypoplasia. Of particular significance is the researcher’s conclusion about the non-local origin of the pre-Sauromatian culture bearers in the Lower Volga region, which is supported by craniological data [28, p. 12]. It should be noted that data on the paleopathology of the population buried in Chernogorovka-type cemeteries from adjacent territories is currently unavailable.

This article analyzes archaeological and paleoanthropological materials from five pre-Sauromatian period (9th – 7th centuries BC) under kurgan burials in the Lower Volga region, most of which have not been previously published and are being introduced into scholarly discourse for the first time.

Methods and materials. The study is based on archaeological and anthropological materials from five burials in the Solodovka I, Lenin II, and Tingutinsky kurgan cemeteries (Volgograd region) and the single Evdyk kurgan (Republic of Kalmykia), dating back to the pre-Sauromatian (pre-Scythian) period – 9th – 7th centuries BC (Fig. 1).

The archaeological analysis of these complexes employed an accepted typological approach using the method of dated analogies.

The anthropological collection consists of skeletal remains of 5 individuals – 4 males and 1 female. The preservation of the anthropological material varies. Sex and age determination was conducted based on cranial and postcranial morphology using the anthropological methods of V.P. Alekseev and G.F. Debets [1] and

-

V.P. Alekseev [2]. Age estimation for adults considered cranial suture closure patterns and dental crown wear [1; 2; 7; 27]. Due to the poor preservation and incompleteness of the paleoanthropological material for objective reasons, the study of the bone remains was based solely on a standard program for assessing the occurrence of pathological conditions on the bones of the postcranial skeleton and the skull [8].

Analysis. Archaeological Context

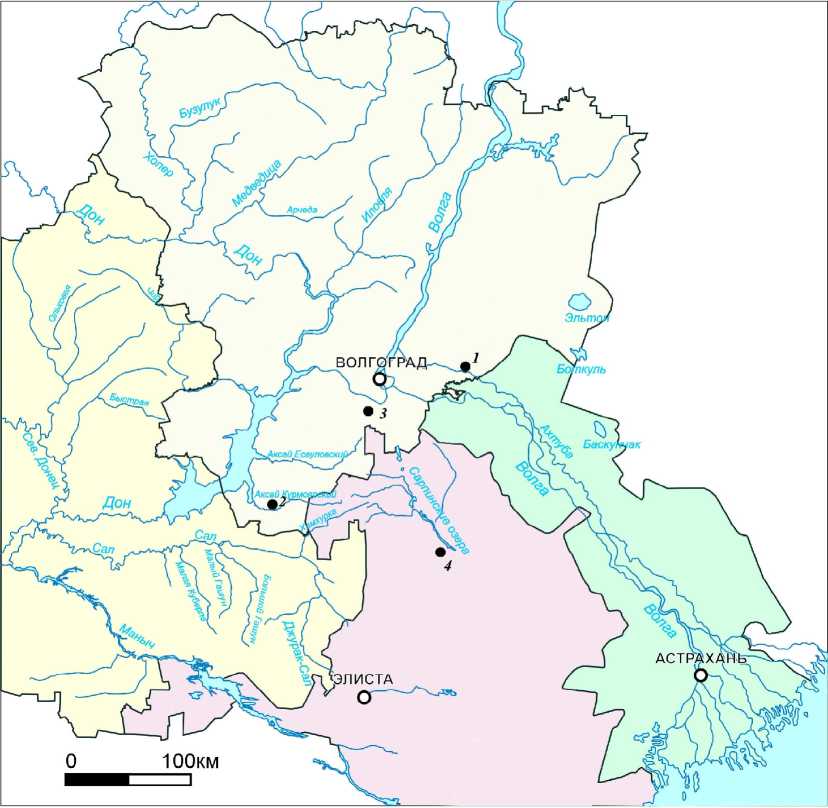

Solodovka I cemetery, kurgan 12, burial 2. The Solodovka I cemetery was located on the left-bank floodplain terrace of the Akhtuba River, 0.2 km northeast of the village of Solodovka in the Volgograd region (Fig. 1). The excavations were conducted in 2002 by the Gulistan archaeological team of the Volga Humanitarian Institute (Volgograd State University) under the supervision of A.A. Glukhov [13]. In kurgan 12, pre-Sauromatian burial 2 was an insertion burial located in the central part of the kurgan. The shape of the grave pit could not be determined. The skeleton of a male aged 25–35 was placed in a flexed position on his left side, tilted forward onto the chest, with the head oriented eastnortheast (ENE). The skull rested on its left side, with the facial bones facing south. The legs were bent at the knees, and the arms were flexed at the elbows, with the forearms positioned in front of the face (Fig. 2, 1 ).

The skeleton of a calf lay above the human skull. The animal’s skeleton was oriented along a south-southwest to north-northeast (SSW–NNE) axis, with the skull facing SSW. Scattered bones of a sheep’s legs and bird bones were also found nearby (Fig. 2, 1 ). No grave goods were present.

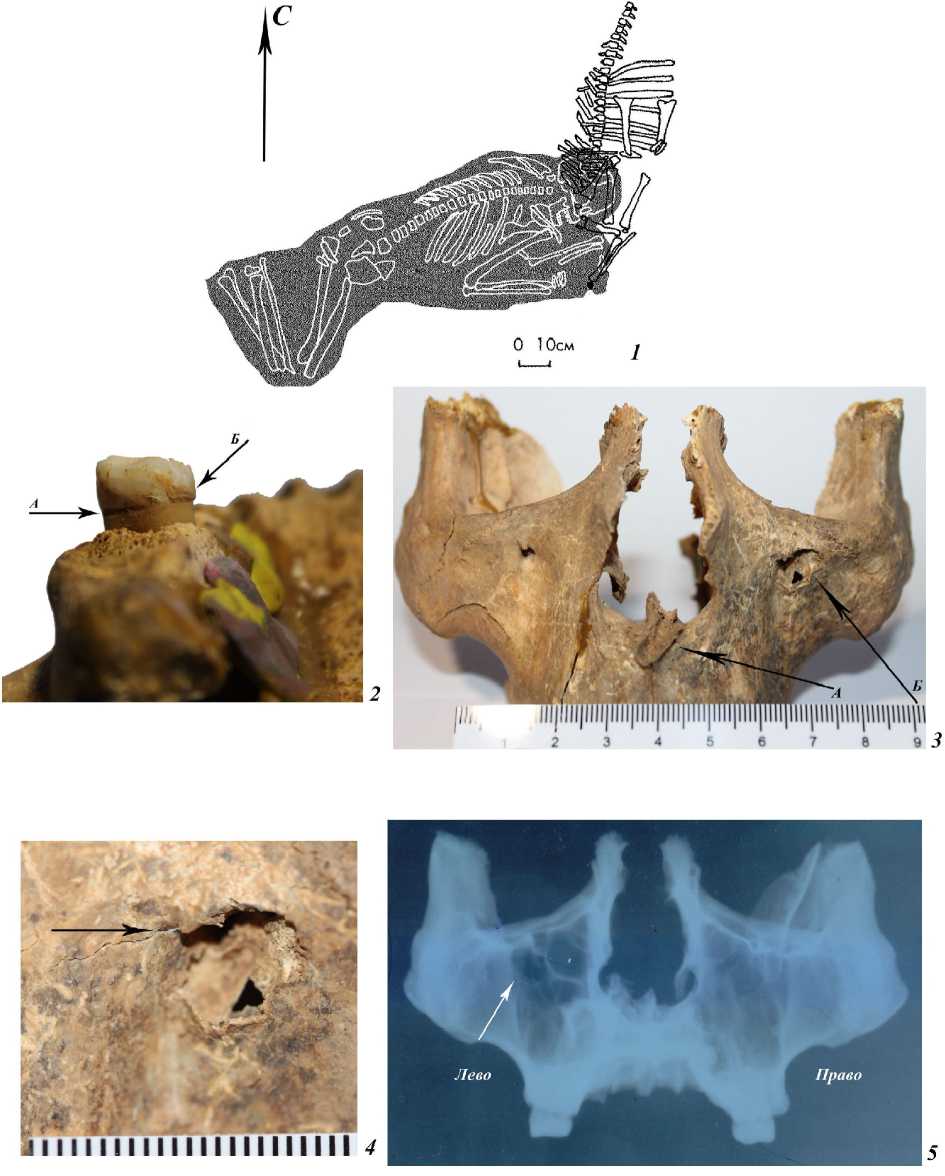

Solodovka I cemetery, kurgan 19, burial 2. Kurgan 19 was also excavated in 2002 by the Gulistan archaeological team of the Volga Humanitarian Institute of Volgograd State University under the supervision ofA.A. Glukhov [13]. The pre-Sauromatian burial 2 was the primary burial in the kurgan. It was placed in an elongated oval grave pit with its long axis oriented west– east (W–E). The southwestern corner of the pit was damaged by the burial structure of Sarmatian burial 4. At the bottom of the pit lay the extended skeleton of a male aged 45–50, originally positioned on his back, likely with his head oriented west. The skull, right humerus, ribs, and spinal column were not preserved: these parts had been destroyed and were found in the backfill of the adjacent burial 4. The left arm bones and the right ulna were extended along the body. The legs were stretched out, with the right leg slightly bent (Fig. 3, 1).

A fragment of the upper part of a clay vessel was found in the fill near the western wall of the grave pit, though its complete form could not be reconstructed. It likely had a jar-like shape with a straight, slightly inward-curving rim. The approximate mouth diameter was 20 cm. Below the rim was a horizontal row of deep indentations (0.7 cm in diameter), alternating with perforations of the same size (Fig. 3, 2 ). The ceramic paste was black in cross-section, with grit temper. The outer surface was also black, while the inner surface had a pinkish hue.

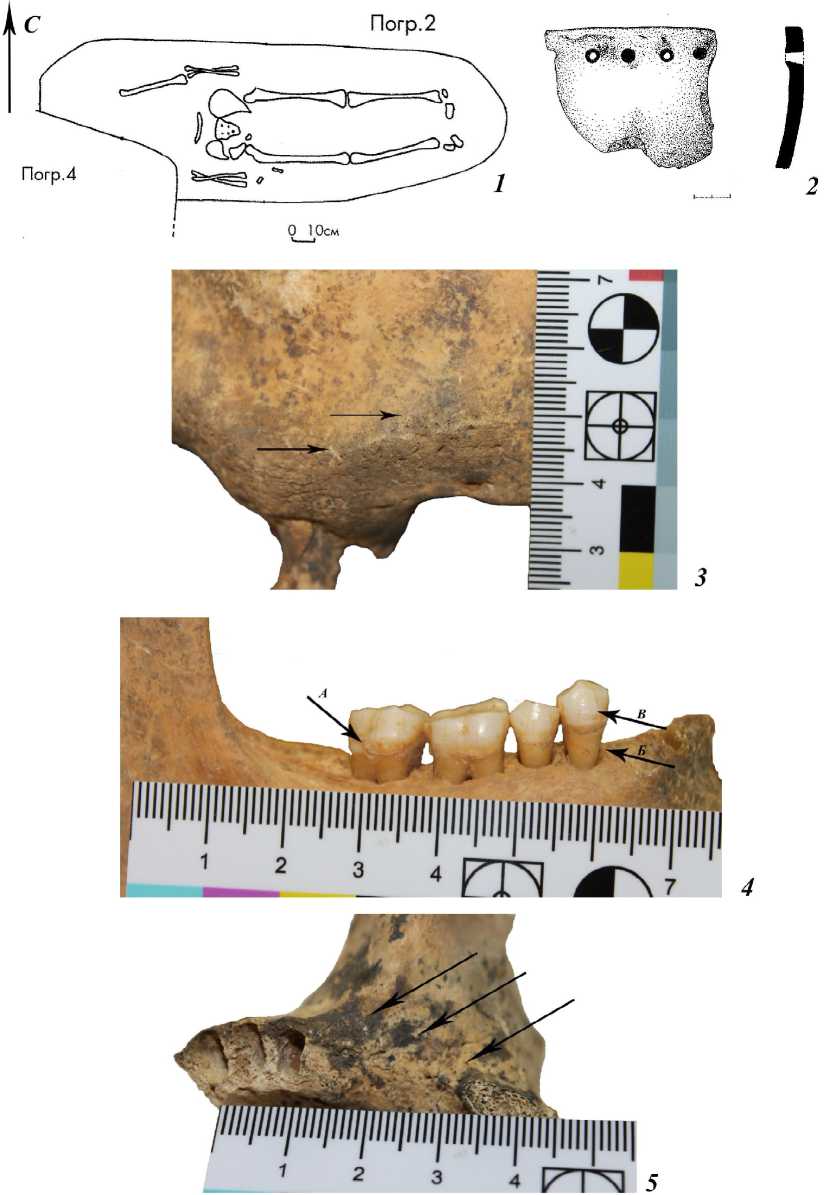

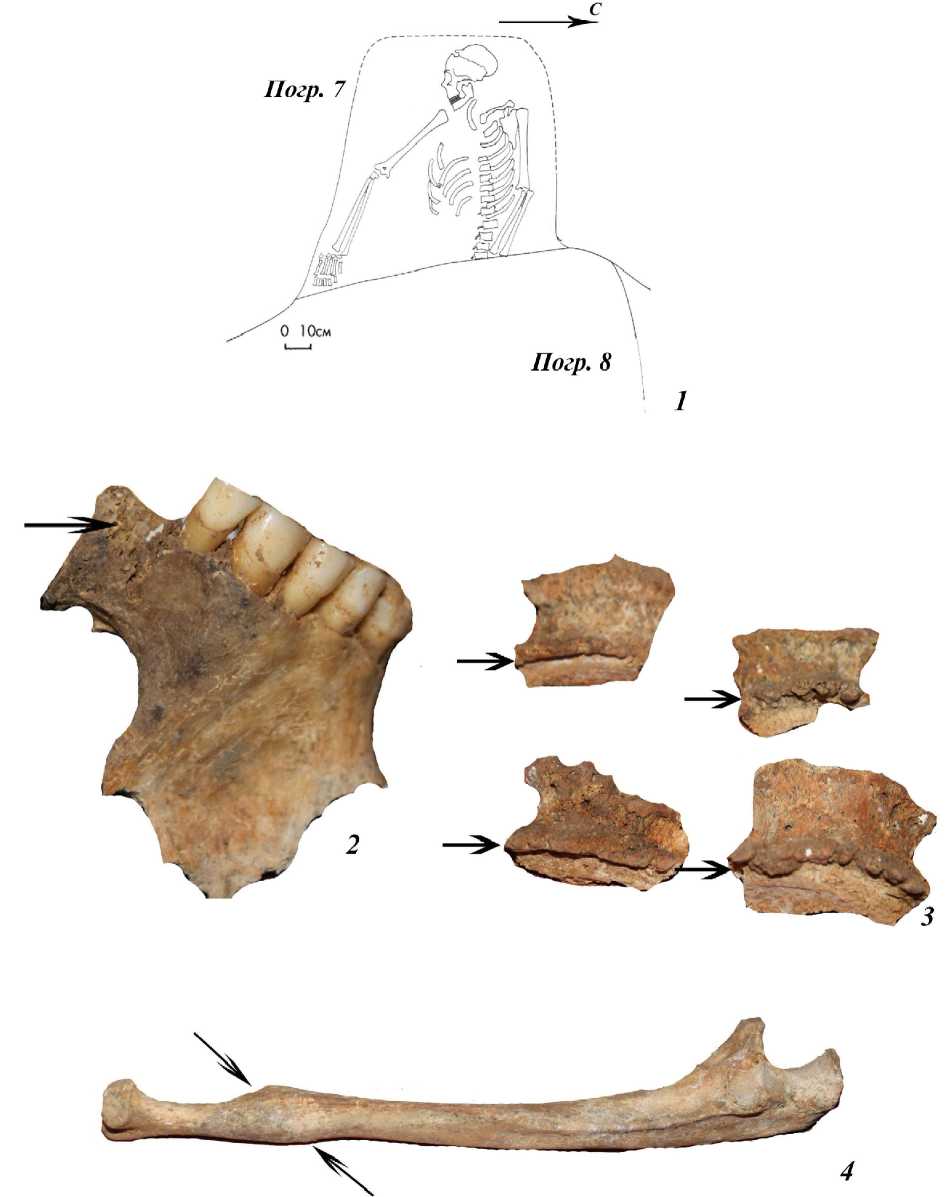

Lenin II cemetery, kurgan 3, burial 7. The cemetery was situated on a coastal terrace of the Aksai Kurmoyarsky River, 2 km west of the settlement named after Lenin in the Kotelnikovsky area, Volgograd region (Fig. 1). Excavations were conducted in 2017 by the expedition of the State Budgetary Cultural Institution of the Volgograd Regional Cultural Heritage Protection Center under the leadership of V.G. Blokhin [6]. Burial 7 was inserted into the central part of the kurgan. The eastern side of the burial structure was completely destroyed by a later Sarmatian insertion burial, which also damaged the lower part of the human skeleton. Judging by the preserved outlines, the grave pit had a sub-rectangular shape, oriented along a west-east (W-E) axis. The pit walls were vertical with a flat bottom. At the bottom of the burial structure, the upper remains of a male aged 30–40 were discovered, lying on his back with a slight turn onto the chest, head oriented west. The skull rested on the right temple, with the facial bones facing south. The bones of the left arm, slightly bent at the elbow, were extended along the torso, while the right arm was stretched and slightly abducted from the body. The right hand lay palm down. The left hand, pelvic bones, and lower limbs were missing, likely removed during later Sarmatian burials (Fig. 4, 1 ). No grave goods were present.

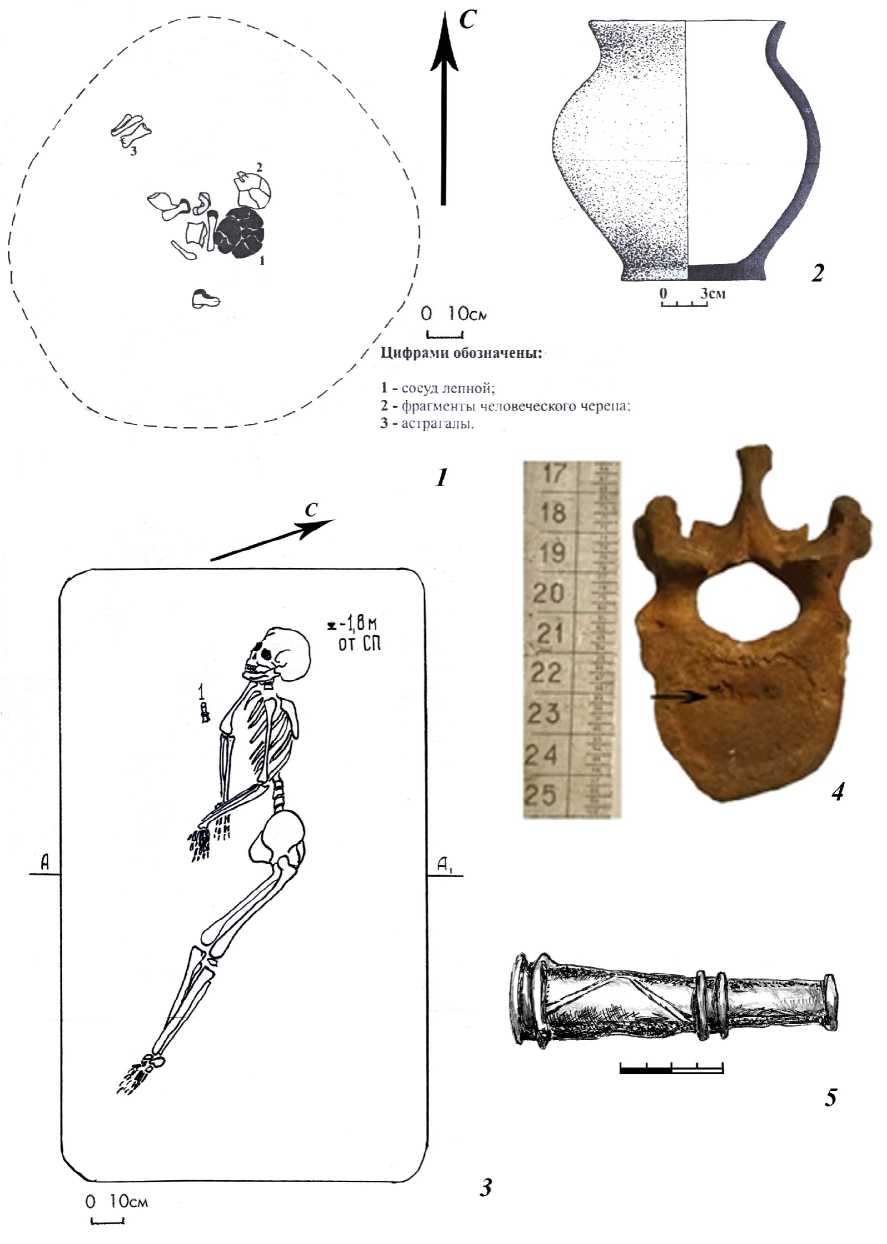

Tingutinsky cemetery, kurgan 2, burial 1. The Tingutinsky kurgan mound (2 mounds) was located in the southern part of the Volga-Don interfluve, Svetloyarsky District, Volgograd region, 2.5 km northeast of Tingut Station. The kurgan group occupied a flat inter-ravine watershed east of the Volgograd-Kotelnikovo railway (Fig. 1). Excavations were conducted in 2014 by the ANO “Research Center for Cultural Heritage Preservation” (Saratov) under the leadership of V.V. Tikhonov. According to the preliminary publication, burial 1 was attributed to the Early Iron Age and interpreted as a Sarmatian burial [37]. But according to a number of characteristic features, this complex exhibits indicators suggesting an earlier pre-Sauromatian (preScythian) “transitional” period affiliation, as argued below.

Burial 1 was an insertion, located 3.1 m west of the kurgan center. The circular grave pit (diameter ~1.1 m) was dug 40 cm into the subsoil. At the bottom lay the disarticulated bones of a male aged 25–35; the body position of the buried individual could not be determined (Fig. 5, 1 ). Among the human bones, a handmade flat-bottomed vessel was found with a rounded, almost spherical body, a short neck, and a low bell-shaped neck. Dimensions of the vessel: height 17.5 cm, max body diameter 17.7 cm, rim diameter 13 cm. The surface is grayish-brown with burnishing traces and soot marks on the exterior/interior. The paste in the fracture is black, tempered with sand and grog (Fig. 5, 2 ). Additionally, animal astragali (likely small cattle) were recovered.

Evdyk single kurgan, burial 5. The Evdyk kurgan was located on a virgin terrace of Lake Sarpа’s southwestern shore, near the eastern outskirts of the Evdyk settlement (Oktyabrsky District, Kalmykia), within the Volga-Chogray Canal construction zone (Fig. 1). The excavations were carried out in 1988 by the Volgograd State University under the supervision of A.V. Lukashov [23]. The large mound had adjacent circular ditches on its NW and SW sides. Burial 5, dated back to the pre-Sauromatian period, was an insertion placed 2 m northeast of the kurgan center. The rectangular pit (2 x 1.2 x 1.8 m) was oriented WNW-ESE. At the bottom lay the female skeleton remains, aged 20–25, in a right-side flexed position with her skull oriented to the west and her face facing south. The right arm extended along the torso; the left arm bent at an obtuse angle, forearm crossing the right wrist. The lower limbs: slightly flexed at the hips but generally extended. Judging by the position of the limb bones, the wrists and shins were tied during burial (Fig. 5, 3 ).

Near the elbow of the right arm lay a bronze conical tubular pendant, 6 cm long, with protruding ring-shaped ridges at the ends and in the middle. One side of the pendant features a relief zigzag pattern (Fig. 5, 5 ).

Paleopathological data

Solodovka I cemetery, 2002, kurgan 12, burial 2. The study examined a fragmented cranial vault with a mandible and an incomplete set of postcranial skeletal bones (humeri, ulnae, radii, lower limb diaphysis, clavicles, scapulae, sternum, and individual ribs). The remains belong to a male who died at 20–25 years of age, as evidenced by incomplete ossification of metaphyseal zones in the ulnae and radii.

Examination of the dental system revealed several anomalies and pathologies. Thus, diastemas were found between the second incisors and canines in both upper and lower jaws. The disturbances of the dental row in the form of crowding of the lower incisors were also noted.

Mineralized deposits (grade 2, light yellow in color) were observed on the preserved tooth crowns (Fig. 2, 2Б ). Horizontally oriented enamel hypoplasia lines were recorded on incisors, canines, and premolars of both jaws, with defect formation occurring at 2–3.5 years of age. Despite the individual’s young age, significant wear was noted on the lower anterior incisors, likely resulting from malocclusion. Slightly exposed roots indicate early-stage periodontitis development. Interproximal grooves were observed on the distal surfaces of the upper first molars (Fig. 2, 2А ).

Among the pathologies of the cranial vault bones, a grade 1 “orange peel” vascular reaction should be noted. The periosteal changes affect the frontal, parietal, and occipital bones.

It is also necessary to point out the curvature of the vomer and deformation of the frontal processes of the maxillary bones, most likely caused by trauma to the nasal area (Figs. 2, 3А ).

Attention should be drawn to the pathology recorded on the right maxillary bone in the area of the infraorbital foramen, through which the eponymous canal passes. The edges of the foramen are widened, sharp, and uneven, with the walls covered by an inflammatory process. The inner surface of the canal also shows traces of periostitis. Radiological examination of the maxillary sinuses revealed the presence of additional trabeculae and bridges within the sinus, as well as signs of sclerosis caused by an inflammatory process in the right maxillary sinuses (Figs. 2, 3Б, 4, 5).

Examination of the postcranial skeleton revealed signs of premature wear in the young individual’s osteoarticular system. Thus, osteoarthritic changes were found in the shoulder, elbow, wrist, knee, sternoclavicular, and acromial joints bilaterally.

Schmorl’s nodes were identified on the 10th, 11th, and 12th thoracic vertebrae, with horizontally oriented osteophytes affecting the 3rd through 5th lumbar vertebrae.

The muscle relief on both upper and lower limbs shows pronounced development. Particularly notable is hypertrophy at the deltoid tuberosity of the humeri, along the lateral edge where m. brachioradialis and m. extensor carpi radialis longus attach. The radial tuberosity (attachment site of m. biceps brachii) shows marked muscle relief. The ulnae exhibit strongly developed supinator crests and distal lateral crests. The clavicles show hypertrophy at the ligamentum costoclaviculare and ligamentum coracoclaviculare attachment sites. Femoral bones display enthesopathies along the entire linea aspera, while the fibulae show ossification of ligamentum tibiofibulare anterior et posterior.

Solodovka I cemetery, 2002, kurgan 19, burial 2. The study examined a damaged cranial capsule missing the right facial skeleton and a partially preserved postcranial skeleton (diaphyses of upper and lower limbs).

Judging by dental wear, cranial suture obliteration, and the presence of degenerative joint changes, the remains belong to a male aged 40– 50 years.

The cranial vault bones show signs of “orange peel” vascular reaction (grade 3 according to A.P. Buzhilova [8]) (Fig. 3, 3 ). The occipital region displays increased bone relief at muscle attachment sites (m. occipitalis, m. rectus capitis posterior minor, m. rectus posterior major). Masticatory muscle attachments on the mandible and cranium are significantly developed.

Dental examination revealed mineralized deposits on the tooth crowns. Enamel hypoplasia was found on the lower left canine as horizontal lines (Fig. 3, 4 А, Б, В ).

The upper jaw shows antemortem loss of left molars (Fig. 3, 5 ). The lower jaw exhibits enamel chips on the left canine and the first premolar. Dental wear is even, with exposed pulp and secondary dentin formation observed on incisors and premolars.

Notable anomalies include a diastema between the second incisor and canine on the right side of the lower jaw.

Most articular surfaces of limb diaphyses were not preserved. However, the study of the long bones revealed signs of deforming arthrosis in the left elbow and the wrist joints. Deformation and marginal osteophytes were observed in the knees and ankle joints of both lower limbs.

The muscle attachment relief on limb diaphyses is well-developed (grade 2), particularly showing hypertrophy at the distal lateral crest of ulnae (m. pronator quadratus attachment) and along the linea aspera of femora.

Lenin II cemetery, 2014, kurgan 3, burial 7. Preserved fragments include the cranial vault, mandible, upper limb bones, clavicles, and selected thoracic/lumbar vertebrae. The robusticity of the remains and the specific cranial features indicate the male sex of the buried individual. Dental wear to dentin and joint degeneration suggest the individual died at 35–40 years of age.

The cranial sutures are unfused, which is inconsistent with the degree of dental wear. The inner surface of the cranial bones exhibits digital impressions. Two triangular Wormian bones (“os triquetrum”) were identified in the occipital region. The external surface of cranial vault bones exhibits a grade 3 “orange peel” vascular reaction.

The occipital region shows pronounced bone relief at muscle attachment sites (m. occipitalis, m. rectus capitis posterior minor, m. rectus posterior major). Masticatory muscle attachments on the mandible and cranium are significantly developed.

Grade 1 light-yellow mineralized deposits were observed on the tooth crowns. Antemortem loss of the right upper first incisor is evident (Fig. 4, 2 ). Enamel chips are present on premolars of both jaws, with exposed tooth roots. An interproximal groove was identified on the right lower first molar.

The shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints show signs of wear. Osteochondrosis signs appear on clavicular acromial ends, with hypertrophied attachment sites for ligamentum costoclaviculare and ligamentum coracoclaviculare. The left ulna displays a completely healed oblique fracture in the distal diaphysis (Fig. 4, 4), showing no inflammatory traces and demonstrating successful healing.

Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae fragments exhibit grade 2 horizontal osteophytosis (Fig. 4, 3 ).

The upper limb muscle attachments show above-average development with right-side dominance. Particularly strong development is noted at m. extensor carpi radialis longus attachment sites on humeri. Scapulae reveal developed attachment areas for m. triceps brachii and m. deltoideus.

Tingutinsky cemetery, 2014, kurgan 2, burial 1 . Small fragments of cranial vault and facial bones, mandible, diaphyseal portions of limb bones, pelvic bone fragments, sacrum, vertebrae, and ribs were available for study. Skeletal analysis indicates the remains belong to a male aged 25–35.

The cranial bones display digital impressions. Additional Wormian bones appear in the occipital suture. The frontal bone shows a grade 3 vascular reaction in the area of the superciliary arches.

Dental examination revealed interproximal grooves on molars and premolars of both jaws, possibly resulting from toothpick use or dental tool utilization. Light-yellow mineralized deposits appear on the crowns, with half-exposed roots indicating periodontosis development. Horizontally oriented enamel hypoplasia lines on the premolars and canines reflect childhood stress episodes (chronic malnutrition/diarrhea) at 2–3 years of age.

Postcranial examination revealed degenerative changes in the right hip and the left knee joints. Pathological manifestations include horizontal osteophytosis and osteochondrosis in thoracic/lumbar vertebrae. Central-oriented cartilage herniations were identified on the 9th thoracic vertebra (Fig. 5, 4 ). Cervical vertebrae exhibit bone growths at the atlas-axis articulation.

Among the anomalies of the postcranial skeleton, lateral facets on distal epiphyses of the tibiae should be noted.

The muscular relief on the long bones and clavicles shows intensive development up to grade 3.

Single kurgan Evdyk, 1988, burial 5. The preserved remains include femora, tibiae, and fibulae. The gracility of long bones suggests the remains belong to a female. Based on epiphyseal fusion evidence, the buried individual died around 20 years of age.

The osteoarticular system shows no signs of excessive wear. Only the medial condyle of the right femur displays minor marginal osteophytes. Another notable feature includes gnawing marks on the medial surface of the right femur slightly below the lesser trochanter.

The muscle attachment relief on the lower limb long bones is generally weakly developed. However, increased development is observed at m. gluteus maximus attachment sites (gluteal tuberosity) on femora. Among the bone anomalies, hypotrochanteric foramina are present on both femora.

Discussion. Despite the geographical dispersion of the studied sites, some variations and “impoverishment” of the material culture in the presented archaeological complexes, and their basic cultural characteristics, we can include the entire sample in the Chernogorovka culture burial antiquities of the pre-Scythian (pre-Sauromatian) Early Iron Age period. The formation of the Chernogorovka culture involved various groups of mobile pastoral and semi-sedentary populations from the Northern Black Sea region, steppe Ciscaucasia, and the Don region. These processes probably also extended to the territory of the Lower Volga region at certain stages.

Like most “transitional” period sites, the published complexes are located near major water systems. The Lenin II and Tingutinsky cemeteries (near the sources of Esaulovsky Aksai, a left tributary of the Don) gravitate towards the Don River and its tributaries; Solodovka I cemetery towards the Akhtuba valley; and Evdyk kurgan towards coastal terraces of Lake Sarpa (Fig. 1). Almost all of them were inserted into existing kurgans, typically in central parts of kurgan mounds. The exception is primary burial 2 in kurgan 1 9 of the Solodovka I cemetery. Regarding grave construction forms, simple rectangular pits with latitudinal orientation dominate this sample. This grave form prevails throughout the Chernogorovka culture area [10; 11; 24; 31]. In one case the grave pit was circular (Tingutinsky cemetery), and in another case the grave form was undetermined (Solodovka I, kurgan 12, burial 2).

The body positions in the sample vary, essentially representing the main postures of the deceased characteristic of Chernogorovka culture burials in general: flexed on the side with head to the east (Solodovka I, kurgan 12), extended on the side, and extended supine with head to the west (Evdyk, Lenin II, Solodovka I kurgan 19). The predominant postures and orientations of the buried may indicate a relatively late chronological position of the sample burials, placing them within the boundaries of the 8th to early 7th centuries BC.

As a rule, the pre-Sauromatian burials in the Lower Volga region contain animal remains, often in the form of carcasses or their parts, which is also noted in the presented materials. This is a very characteristic cultural indicator that should be taken into account, especially when determining the cultural-chronological attribution of burials without inventory.

The burial inventory of the sample is few in number but quite interesting in its own way. The ceramic collection consists of a vessel from the Tingutinsky cemetery (Fig. 5, 2 ) and a fragment of a pot from kurgan 19 of the Solodovka I cemetery (Fig. 3, 2 ).

Of particular interest is the vase-shaped vessel on a distinct base from the Tingutinsky cemetery. Its form and polishing techniques have no analogues in the local Late and Final Bronze Age pottery; this type of tableware was clearly introduced to the Lower Volga region from outside. At the same time, similar ceramics are present in pre-Scythian antiquities of the 9th – 8th centuries BC in adjacent regions – the Lower and Middle Don regions, the steppe Ciscaucasia, and the Northern Black Sea region – and not only in burial sites but also in synchronous settlement sites [24, pp. 170-175; 34, p. 8, 38, table XVIII; 39].

The ceramic fragment from kurgan 19 of the Solodovka I cemetery belongs to a different type of pottery – weakly profiled pots, including jar-shaped forms. Below the rim, there is an ornament consisting of a circular row of deep punctures made with the end of a stick, alternating with through holes. This primitive form of tableware, widespread in the preceding Late and Final Bronze Age of the Lower Volga region, would become perhaps the most common in the Early Iron Age, primarily in the Sauromatian material complex. K.F. Smirnov attributed this type of pottery to the “transitional” period, dating back to the 8th – 7th centuries BC [36, table 6]. Apparently, burial 2 was made no earlier than the mid-8th century BC, and possibly somewhat later, including the first half of the 7th century BC.

The only metal artifact among the presented burial complexes is a unique cast bronze tube (or pendant, bead) of an elongated-conical shape from the Evdyk kurgan (Fig. 5, 5 ). We know of no direct parallels to this artifact in pre-Sauromatian period burials either in the Volga-Urals region or the Volga-Don interfluve. Only in the material collection of the Yerzovka I settlement, located on the right bank of the Volgograd Reservoir north of Volgograd, was an identical artifact (8 cm long) found in layers containing so-called “Nur-type” pottery transitional to the Early Iron Age [12, pp. 124, 125]. The closest parallels to these tubes can be found only in materials of the Ananyino culture from the Volga-Kama region – nearly a thousand kilometers northeast of Volgograd. There, in early Ananyino cemeteries such as Starshij Akhmylovsky or Tetyushsky, such “tubular pendants” or “tubular beads” (according to A.Kh. Khalikov) represent a common category of bronze artifacts [14, pp. 30, 31, 59, 61]. Considering the date of the early Ananyino phase (9th – first quarter of 7th centuries BC) [21, p. 25], the pre-Sauromatian burial 5 in the Evdyk kurgan should apparently be dated back to the same period, with a more narrow timeframe within the 8th century BC. Thus, the most optimal combined dating for the published burials from the Lower Volga region is the 8th – early 7th centuries BC.

When evaluating the pathological conditions observed on skeletal remains from these 9th – 7th century BC archaeological complexes, we should highlight several key criteria.

First of all, it should be noted that the group shows no evidence of caries or abscesses, while three individuals exhibited antemortem tooth loss. The latter observation is probably due to the fact that practically all individuals, regardless of age, showed severe dental wear that sometimes exposed the pulp. This led to inflammatory processes in the periodontal area. It’s also important to note that all individuals with preserved teeth or jaw fragments showed signs of periodontitis development and dental calculus deposits. We should also mention the presence of interproximal grooves in three males, associated with the use of mechanical toothpicks.

All of the above-mentioned conditions indicate a specific dietary pattern among the pre-Sauromatian population, which was likely based on foods with high animal protein content and had a viscous consistency. The significant chewing effort required for such a meat-heavy diet is further evidenced by cases of temporomandibular joint arthrosis found in both male and female individuals.

A similar complex of dental pathologies has been identified among nomadic populations of Sarmatian cultures from the 4th – 1st centuries BC, 1st – 2nd centuries AD, and 2nd – 4th centuries AD, as well as among Early and Middle Bronze Age pastoralists of the Lower Volga region and Sauromatian period nomads [29; 30].

Enamel hypoplasia was observed in half of the studied individuals, indicating childhood stress periods when the body is most vulnerable to negative factors such as intestinal diseases, poisoning, infections, and parasites [15, p. 97]. Accordingly, half of all pre-Sauromatian nomads experienced stress periods in childhood.

A single case of “cribra orbitalia” (CO) was recorded in a 35–40-year-old female from the Vesely I cemetery. This pathology appears to be an isolated case. It is generally accepted that CO serves as an indicator of generalized stress resulting from a high pathogenic load [28, pp. 9].

Notably, all pre-Sauromatian individuals showed an “orange peel” vascular reaction on their cranial vaults. This condition develops as a consequence of cold stress from regular exposure to open air in windy, cold, or humid weather conditions [8, pp. 104-105; 3, pp. 52-53; 30, p. 149]. It may also result from activation of peripheral blood circulation in head soft tissues during specific labor activities or under increased pressure [9, p. 44; 26, p. 52].

The studied individuals exhibited various traumatic injuries. The male from burial 2 of kurgan 19 showed nasal trauma. The male from Lenin II cemetery had a fracture of the left ulna. This same male also displayed antemortem loss of the right upper first incisor with subsequent alveolar healing – a condition that could also result from trauma caused by a frontal impact. We should also note the cartilage hernia in the male from Tingut cemetery. The main causes of such conditions include spinal trauma, normal aging processes of the spine, and high physical activity

[15, p. 186; 18, pp. 94-95; 20, pp. 146-147; 32, p. 27; 40, p. 45].

The high frequency of injuries in the studied group supports previously proposed theories about elevated social and political tensions in the Volga-Don steppes during the 9th – 7th centuries BC [28].

The population’s high physical activity is further evidenced by spinal and joint pathologies. Moreover, degenerative-dystrophic changes were observed in both young and elderly individuals. Due to poor representativeness of paleoanthropological material, it is difficult to conclusively state that these populations spent extended periods horseback riding. However, the nature of the identified pathological conditions and degree of muscle attachment development do not exclude this possibility.

Conclusions. The probable dating of the pre-Sauromatian burials from the Lower Volga region examined in this publication falls within the 8th – early 7th centuries BC.

The most characteristic feature of archaeological complexes from this period in the Lower Volga region is the “impoverishment” of material culture, which may serve as an important cultural marker of Chernogorovka culture burial antiquities from the pre-Scythian (pre-Sauromatian) period. This factor should be particularly considered when interpreting burials without inventory.

Pre-Sauromatian burials in the Lower Volga region are predominantly secondary insertions. Grave pits are mainly sub-rectangular in shape. The deceased are typically positioned in flexed or semiflexed positions on their sides, often extended, with heads oriented east or west. Burials frequently contain animal remains, distinctive ceramics, and occasional metal artifacts.

Analysis of pathological features in individuals from pre-Sauromatian burials suggests their diet consisted primarily of viscous, solid foods rich in animal protein.

The life of Early Iron Age nomads was challenging. Traumas and markers of intense physical activity indicate social tensions within the community, likely related to competition for resources under changing conditions. Signs of episodic (enamel hypoplasia) and specific stress (iron-deficiency anemia markers) show that some nomads of this period experienced childhood stress. Indicators of negative environmental (vascular reactions) and social impacts (traumas, arthrosis, and spinal pathologies) suggest that communities of the 9th – 7th centuries BC maintained high mobility levels.

It cannot be ruled out that part of the population at this time could have been riding a horse for a long time, as indicated by pathologies of the spinal column, degenerative joint changes, and characteristic muscle attachment development patterns on long bones of the skeleton.

A CKNO WLEDGEMENTS

-

1 The authors express their gratitude to A.A. Glukhov, Candidate of Sciences (History), Director of the “Volga Research and Production Center for Archaeological Research and Expertise,” and to E.A. Kekeev, Junior Researcher of the Kalmyk Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, for the opportunity to work with and publish archival materials.

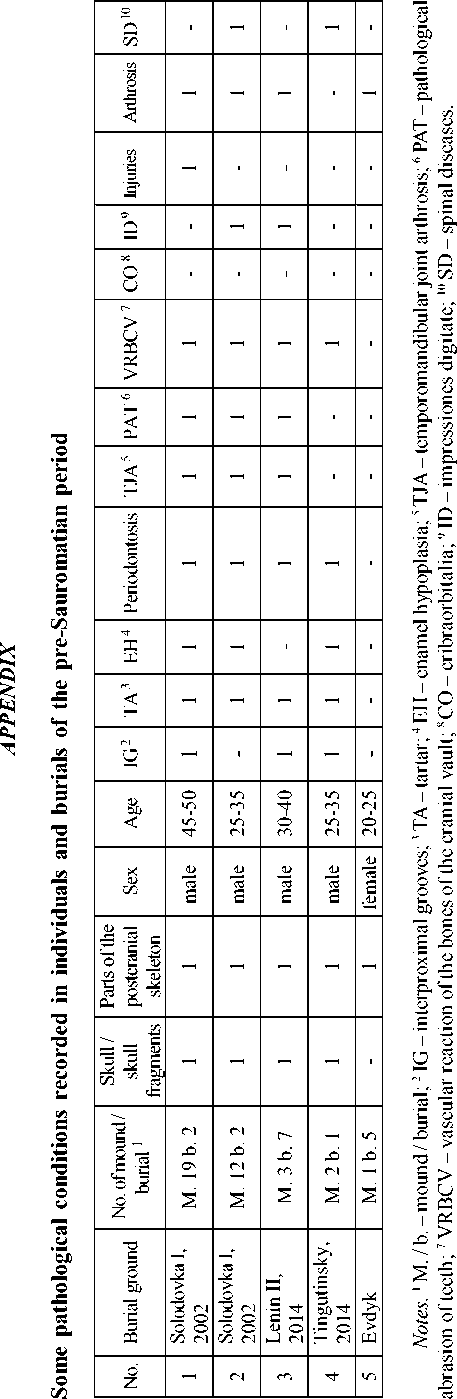

Fig. 1. Location map of pre-Sauromatian period burial sites in the Lower Volga region:

1 – Lenin II kurgan cemetery, 2 – Solodovka I kurgan cemetery, 3 – Tingutinsky kurgan cemetery, 4 – Evdyk cemetery

Fig. 2. Burial plan and pathological features of a skeleton from burial 2, mound 12, Solodovka I cemetery:

1 – plan of burial 2, kurgan 12, Solodovka I cemetery; 2 , A – interproximal groove on the distal surface of the right upper first molar in a male from burial 2, kurgan 12, Solodovka I cemetery, Б – dental calculus (tartar);

-

3 , A – curvature of the anterior nasal spine; Б – expansion of the infraorbital canal in the right maxilla;

-

4 – enlarged view of the expanded infraorbital canal in the right maxilla showing signs of inflammatory process;

-

5 – radiograph of the facial portion of the skull of a male from burial 2, kurgan 12, Solodovka I cemetery

Погр.4

Погр.2

О 10см

Fig. 3. Burial plan and paleopathological features of an individual buried in burial 2, mound 19, Solodovka I cemetery:

1 – plan of burial 2, kurgan 19, Solodovka I cemetery; 2 – ceramic fragment found in burial 2, kurgan 19, Solodovka I cemetery; 3 – signs of vascular reaction on the frontal bone in the supraorbital region of a male from burial 2, kurgan 19, Solodovka I cemetery;

4 , A – dental calculus; Б – exposed tooth roots; В – horizontal enamel hypoplasia on the lower jaw first premolar;

5 – antemortem loss of left upper molars in a male from burial 2, kurgan 19, Solodovka I cemetery

Fig. 4. Burial plan and paleopathological features on the skeletal remains of a man from burial 7, mound 3, Lenin II cemetery:

1 – plan of burial 7, kurgan 3, Lenin II cemetery; 2 – evidence of antemortem loss of the right upper first incisor in a 35–40 year old male from burial 7, kurgan 3, Lenin II cemetery;

3 – osteophytosis of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae; 4 – healed fracture traces on the distal diaphysis of the left ulna in a male from burial 7, kurgan 3, Lenin II cemetery

Fig. 5. Burial plan, artifacts and pathological abnormalities from burials at the Tingutinsky cemetery and the Evdyk mound:

1 – plan of burial 1, kurgan 2, Tingutinsky cemetery; 2 – handmade vessel from burial 1, kurgan 2, Tingutinsky cemetery; 3 – plan of burial 5, kurgan 1, Evdyk; 4 – Schmorl’s node on a thoracic vertebra of a male from burial 1, kurgan 2, Tingutinsky cemetery; 5 – copper tube from burial 5, kurgan 1, Evdyk