Psychological time and economic attitudes: testing the theoretical model

Автор: Zabelina E.V., Deyneka O.S., Nestik T.A.

Рубрика: Психология

Статья в выпуске: 1 (25), 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Despite the evidence of the relationship between types of the economic behaviors and certain components of psychological time, there is no holistic model, explaining the relationship between them. The purpose of this study is to develop and verify such a model. According to the theoretical model, psychological time can act as an internal factor, which, when interacting with other internal and external variables, serves as a predictor of changes in economic attitudes. Model verifi cation was carried out on the sample of the residents of the south-western part of the Russian Federation ( N = 1 356, MAge 25.27, 41% of male). We use the following methods: Life Satisfaction Scale, PVQ-RR, Subjective Income Level Scale, Economic Attitudes Questionnaire, Inventory of Polychronic Values, Attitudes towards Time, Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory, Inventory of Time Value as an Economic Resource by Usunier. The empirical model confi rms the theoretical one. The escapist orientation (the combination of orientation to the past negative, present fatalistic and present hedonistic) contributes to the reduction of the level of subjective economic well-being. On the contrary, the harmonious orientation (the combination of the future orientation, past positive and present hedonistic) increases the level of subjective economic well-being indirectly - through the shaping of the future confi dence based on fi nancial literacy. The signifi cant contribution of life values and the less signifi cant contribution of gender and age in shaping the time orientations were found. The study contributes to the understanding of the signifi cance of the perception and experience of time in the economic life for the formation of one’s well-being.

Psychological time, economic attitude, economic behavior, time attitude, time perspective, economic well-being

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170205758

IDR: 170205758 | УДК: 159.9 | DOI: 10.47475/2409-4102-2024-25-1-58-73

Текст научной статьи Psychological time and economic attitudes: testing the theoretical model

Time as an irreplaceable life resource has always had a high value in people’s lives, but it has become particularly important in the recent years as a category of social mind [20]. In the information society time in one’s perception is accelerated and compressed [38]. In the fast flow of information, less time is left for thinking and making economic decisions. This phenomenon called “time-pressure illusion” [8] may cause the negative psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, insecurity, depression, etc., and, as a consequence, lead to reducing the subjective well-being, including economic one.

Psychological time of an individual is the universal and voluminous term for description of various aspects of subjective time phenomenon (perception and experience of time, attitude to time, time orientation, etc.). In general, psychological time is understood as a set of psychically mediated perception, representation, experience and attitude to the physical time of life, caused by social, historical, global conditions. Nowadays there is growing evidence that one’s experience depends on how a person perceives time, processes information over time, and uses his or her memory structures [13].

Despite the evidence of the relationship between types of the economic behaviors and certain components of psychological time [3; 22, 7; 12], there is no comprehensive model of their relationship, including possible determinants and effects. The studies of psychological time in the economic psychology are rather fragmentary, and they use different theoretical concepts. The limitations of theoretical and empirical re- search in this area, combined with the social relevance of the problem, provides the need to develop a holistic theoretical model of the relationship between psychological time and economic mind of an individual, and to verify it on the Russian sample.

Theoretical Model

Psychological time in the economic sphere. Despite the rich theoretical and empirical material in the field of psychological time phenomenon, there is no unity in researchers’ opinions on it. The very construct of psychological time appears in various terms, such as temporal orientation [19], time attitude [23; 29], polychronicity [5], time perspective [40], temporal focus [36], experience of time [16], relation to time [25; 20], and others.

The most complete model is seemed to be a relation to time by Nestik [20]. Within the framework of this model, the structure of psychological time is proposed, both at the individual and at the group (social) levels. The model includes four components of relation to time: value-motivational (the subjective significance of time as an irreplaceable resource); cognitive (time perspective, temporal aspects of identity); affective-evaluative (the emotional attitude to time) and conative one (preferred ways of time organizing) [20].

If we extend this model to the economic sphere, we can assume certain characteristics of psychological time, manifested in economic mind and behavior (table 1).

It is possible to define psychological time in the economic sphere as a mental reality that reflects the simultaneity, sequence, duration, speed of events in

Table 1

Structure and content of psychological time in the economic sphere

Economic mind and psychological time

One of the promising methodological approaches to the study of the phenomena of economic psychology is studying them in the structure of economic mind [9]. Economic mind can be defined as an integral system of the reflection of objective economic reality. It can include such components as representations (of oneself as an economic actor, of the material welfare, wealth; of the rich and the poor people, of profitable activities, of the property and the owner), social attitudes to different forms of economic behavior; attitude to money; psychological readiness for competition with other people in the economic sphere; the orientation to economic value [41], and others. However, economic attitudes are most often studied in the structure of economic mind. In particular, studies have been conducted on attitudes to unemployment [21], savings [15], debt in consumer behavior [27], money [14], as well as investment [2] and entrepreneurial ones [39].

There are evidence about associations between economic mind (behavior) and psychological time. The characteristics of psychological time of consumers are investigated [3; 17; 19]. It is studied the impact of time perception on saving behaviors [22], work motivation [32], entrepreneurial behaviors [4], the behavior of unemployed people [7], and on economic expectations [12; 24]. However, despite the above-mentioned evidence of this relationship, no coherent model of the relationship between psychological time and economic consciousness has been found.

Determinants and effects of psychological time in the economic sphere

One of the factors that influence how a person perceives and experiences time in economic sphere are values . In the humanities, it is customary to distinguish between cultural (established historically) [18], social (determined by a specific social situation) [26], and individual values (determined by the worldview of a particular person) [33]. For instance, the concept of personal organization of life time and activity time [1] shows the dominant role of the individual life values in the construction of life time, including economic sphere.

In science, attempts are made to study the age-related aspects of psychological time in the economics that show a complex, ambiguous relationship between age and subjectively experienced time in different countries. The researchers [35] conclude that age-related changes in time perspective are complex, they are described by curved functions, with peaks and dips in different age cohorts. A common trend for all countries is that the role of the Present Hedonistic factor decreases with age (the time of various experiments passes) and the role of the future orientation increases (the time of activity in the professional sphere, in family matters, etc.) until older age when Present Fatalistic begins to prevail [35].

Gender as a factor influencing the specifics of psychological time and its components also attracts the attention of the researchers. In particular, it is revealed that women in Russia, the United States, and Spain scored higher on the Past Positive and Present Fatalistic scales than men. Women experience warmer and sentimental feelings about their past, they are more prone to nostalgia, to indulge in pleasant memories. Older women tend to have a fatalistic, helpless attitude towards the present, the conviction that the present should be accepted with submission and humility. The same pattern was observed in Italy and Spain [35].

There are the studies of the impact of income and social status on the perception and attitude to time in the economics. A number of researchers, studying time perspective, note the role of lifestyle in the individual perception of time, due to background, cultural education, social status, current task and other factors [40]. It is shown that the tendency to manage future life events is associated with a higher socio-economic level of the respondents [35]. According to K. Muzdy-baev [28], experiencing time is closely related to in- come and success in life: the higher the income level, the longer the time perspective. Recent data on the relationship of the future time orientation with the level of income and socio-economic status of the family are confirmed in the studies of international psychologists [30].

The data collected in science demonstrate the relationship between subjective time and positive psychological phenomena as a consequence of a particular set of time components. For example, time perspective has been shown to be associated with job and life satisfaction [36], locus of control [31], optimism [34], and others. The most theoretically and empirically developed is the relationship between the components of psychological time and life satisfaction , or subjective well-being . This phenomenon can be considered as a consequence, or effect of psychological time, since perception, experience and attitude to time can increase or decrease the level of subjective well-being of a person [6]. It is shown that a balanced time perspective is associated with higher well-being and wisdom throughout life (at different ages) [37]. Respondents with a balanced time perspective felt significantly happier than the others [6].

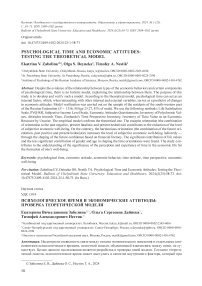

According to analysis, the psychological time of an individual can act as an internal factor, which, when interacting with other internal and external variables, serves as an important predictor of changes in economic mind and behavior. This idea, based on the model of Drobysheva and Zhuravlev [11], can be represented graphically as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A priori model of the relationship between economic mind and psychological time

Changes in the external economic environment (economic growth, stagnation or crisis), entail a whole range of manifestations in economic reality (for example, an increase in the cost of goods and services, an increase or decrease in personal economic income, job loss, promotion, etc.), which in turn can be considered as the reasons for the transformation of economic mind. External factors that affect economic mind can be demographic variables (gender, age, education), social status, professional activity, lifestyle, and others. Internal factors (personal characteristics, intelligence, addictions, values, beliefs) also have an impact on economic mind, along with external factors and in interaction with them. Psychological time of an individual, being in fact an internal factor, and closely related to the value system, can act as a mediator between external factors and economic mind (behavior). As a criterion for demonstration of the changes in one’s economic mind, we can suggest subjective economic well-being as an integral psychological indicator of a person’s life, expressing an attitude to one’s current and future material well-being [24].

The developed model allowed to formulate the main hypothesis of the study: individual components of psychological time (time orientations), determined by demographic, social, cultural and psychological factors, influence the subjective economic well-being, both directly and indirectly through economic attitudes.

Method and sample. In order to study the content of the value-motivational component of the psychological time of an individual, the Inventory of Time Value as an Economic Resource by Usunier [20] was used. To study the content of the cognitive component of psychological time, Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory [35] was used. For studying the content of the emotional component of psychological time of an individual, a method Attitudes towards Time [29] was used. To study the content of the behavioral component of the psychological time of the individual, The Inventory of Polychronic Values [20] was used. In order to diagnose the features of economic mind we used the Economic Attitudes [10]. To explore the psychological variables as the predictors of psychological time we diagnose the individual life values by Schwartz’s PVQ-RR [33]. The Subjective Income Level Scale by A. Furhnem in the adaptation of Deyneka [9] was used to explore the level of subjective economic well-being.

When processing the data, a statistical package SPSS24.0 was used, including the structural equation software IBM SPSS AMOS22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). To aggregate the variables in the model exploratory factor analysis was applied using the maximum likelihood method.

Model verification was carried out on the sample of the residents of the south-western part of the Russian Federation (Chelyabinsk and Sverdlovsk regions) of the number of 1356 people (18–73 years, mean age 25.27 years, 41 % of male). The sample consisted of the university students, employees of public and private sector enterprises, civil servants, entrepreneurs, unemployed, and retirees. The sample was randomly designed to reflect the general population of people living in the area. Most of the data was collected electronically via the Internet.

Design. The study has several stages. At the first stage, the factor (exploratory and confirmatory) analyses were carried out using the Maximum likelihood method to establish the structure of psychological time (Table 2, 3, Figure 2) and economic attitudes (Table 4, 5, Figure 3). Further, according to the theoretical model (Figure 1), the model of the impact of psychological time on economic attitudes was tested (Table 6, Figure 4). The next stages additional elements were added to the model consistently, in particular, subjective economic well-being as the criterion of the efficient self-realization in the economic sphere (Table 7, Figure 5), demographic variables (age and gender), and life values (Table 8, Figure 6). As a result, an empirical model was obtained that corresponds well to the initial data.

Results. Exploratory factor analysis of the studied components of psychological time allowed us to identify three factors in its structure (Table 2).

The first factor, called as a Depreciating time orientation , is formed by the attitude to the events of the future, present, and past as unpleasant, sad, hopeless, meaningless, and poorly controlled. The second factor, named as an Escapist time orientation , includes orientation to the past negative (concentration on unpleasant memories), to the fatalistic perception of the events (as uncontrolled and unmanageable), as well as to the present hedonistic (the attitude to enjoy the current moment, to live “like the last time”). This factor reflects the “stuck in the negative”, the belief that life is a series of troubles and disappointments that can not be influenced in any way, so there is no point to plan the future, one just needs to have fun while it is possible. This factor can be considered as a negative psychological tendency that leads to “killing” time,

Table 2

Factor structure of psychological time

|

Factors |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Negative attitude to the future |

0.878 |

||

|

Negative attitude to the present |

0.865 |

||

|

Negative attitude to the past |

0.722 |

||

|

Past Negative |

0.793 |

||

|

Present Fatalistic |

0.767 |

||

|

Present Hedonistic |

0.577 |

0.495 |

|

|

Past Positive |

0.755 |

||

|

Future |

0.641 |

||

|

The proportion of explained variance, % |

21.9 |

16 |

12.9 |

thoughtless spending it in various activities — surrogates of real healthy life (search for entertainment in virtual reality, computer games, drug intoxication, etc.). This tendency is a risk in terms of the ease of external control of this type of consciousness. Finally, the third factor, labeled Harmonious time orientation , represented by a set of orientation on past positive (bright, happy memories of past events), orientation toward the future (the desire to plan and manage one’s life) and present hedonistic (the desire to enjoy the moment). This factor seems to reflect a balanced time perspective, when a person, appreciating the present, draws resources from the past and builds the future.

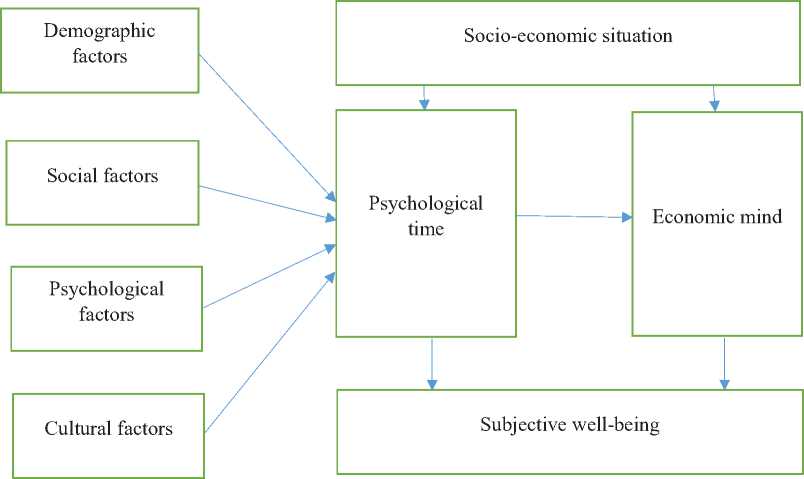

Confirmatory analysis showed the validity of the selected factors (Figure 2). The resulting model corresponds well to the original one according to the consent indices: CMIN = 34.297; df = 9; p = 0.000; GFI = 0.994; CFI = 0.995; RMSEA = 0.045, Pclose = 0.682. All the relationships and coefficients presented in it are statistically reliable (Table 3).

At the next stage, a similar procedure of factor analysis was carried out to determine the structure of economic attitudes, after which the factors were calculated and used in the model as explicit variables. Exploratory factor analysis allowed us to identify 4 factors in the structure of economic attitudes (Table 4).

The first factor is formed by a combination of confidence in the future due to savings, awareness of one’s own financial literacy and satisfaction with the opportunities of consumption. This factor reflects positive emotions (states) in the economic sphere — confidence and satisfaction in the economic life based

Table 3

The regression coefficients of the model of psychological time

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|

|

ОБ ← НЭ |

1.000 |

|||

|

ОН ← НЭ |

0.960 |

0.027 |

34.939 |

*** |

|

ОП ← НЭ |

0.765 |

0.025 |

30.783 |

*** |

|

НП ← НК |

1.000 |

|||

|

ФН ← НК |

1.074 |

0.046 |

23.198 |

*** |

|

ГН ← НК |

0.484 |

0.029 |

16.879 |

*** |

|

ПП ← ПК |

1.000 |

|||

|

Б ← ПК |

0.873 |

0.047 |

18.386 |

*** |

|

ГН ← ПК |

0.631 |

0.040 |

15.808 |

*** |

Note: OБ — negative attitude to the future, OН — negative attitude to the present, OП — negative attitude to the past, НП — past negative, ФН — present fatalistic, ГН — present hedonistic, ПП — past positive, Б — future.

on financial knowledge . The second factor includes the attitude to independent achievements in the field of economics, awareness of the irrationality of the consumer behavior and the attitude to savings. This factor seems to reflect the strategy of rational economic behavior based on savings . The third factor includes attitudes of financial optimism, the desire to occupy the status of a wealthy person, high claims in the economic sphere, interest and activity in the real estate sector, as well as the willingness to invest in profitable risky projects. In general, this factor reflects

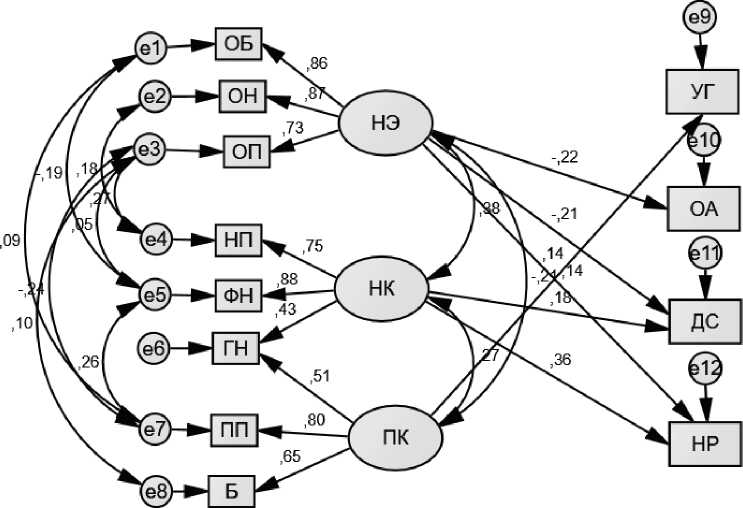

CMIN=34,297; df=9; p=,000; CFI=,995; RMSEA=,045; GFI=,994; Pcose=,682

Figure 2. Model of psychological time

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, OН — attitude to the present, OП — attitude to the past, НП — past negative, ФН — present fatalistic, ГН — present hedonistic, ПП — past positive, Б — future

Table 4

Factor structure of economic attitudes

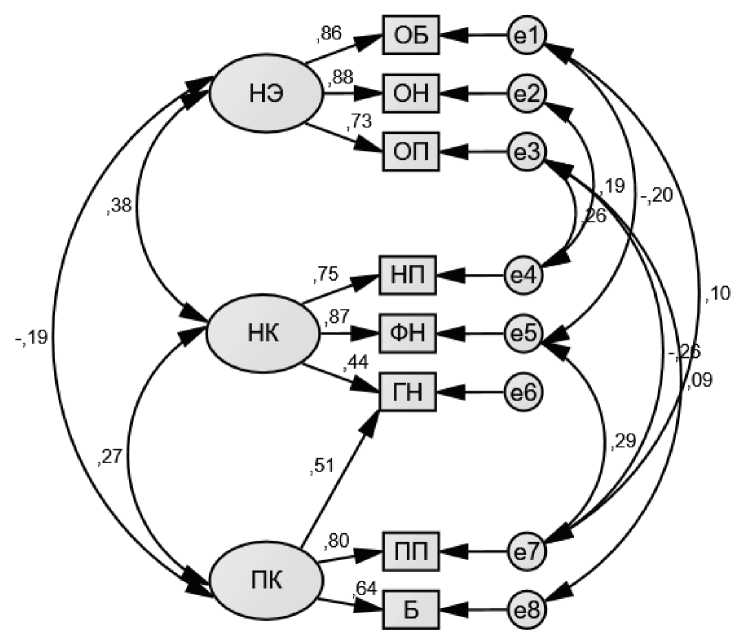

Confirmatory factor analysis verified the four-factor structure of economic attitudes (Figure 3). In general, the resulting model shows acceptable model indices CMIN = 151.256; df = 47; p = 0.000; GFI = 0.984; CFI = 0.959; RMSEA = 0.040, Pclose = 0.992. All the coefficients and relationships presented in it are statistically reliable (Table 5).

At the next stage, in order to test the hypothesis about the influence of the time orientations on the eco- nomics attitudes, an a priori (theoretical) model was verified. The results of the structural equations modeling (Fig. 4) show an acceptable correspondence of the initial model to the consent indices: CMIN = 312.865; df = 40; p = 0.000; GFI = 0.964; CFI = 0.948; RMSEA = 0.070, Pclose = 0.000. Regression coefficients of the model show statistical reliability (Table 6).

The depreciating orientation (negative attitude to the events of the future, present, and past) reduces the focus on the use of both active and passive economic strategies (saving, investing), as well as the level of claims in the field of economics and the level of financial optimism. At the same time, the negative emotional perception of time reinforces the attitudes of the “hired worker”, who is ready to work at the expense of health and vocation, and who despises entrepreneurs. These attitudes are also reinforced by the escapist orientation (orientation to the past negative, present fatalistic, and present hedonistic). Besides, this component contributes to the shaping of a savings mindset (probably savings for a “rainy day”). The harmonious time

CMIN=151,256; df=47; p=,000; CFI=,959; RMSEA=,040; GFI=,984; Pcose=,992

Figure 3. Model of the structure of economic attitudes

Note: ЭА2 — consumer satisfaction, ЭА3 — the desire to save, ЭА4 — confidence in the future thanks to savings, ЭА5 — financial literacy, ЭА11 — the value of independent economic decisions, ЭА12 — economic ambitions, ЭА13 — negative attitude to entrepreneurs, ЭА14 — activity in the real estate sector, ЭА15 — financial optimism, ЭА16 — the priority of earnings over vocation, ЭА18 — awareness of consumer irrationality, ЭА21 — the priority of earnings over health

Table 5

Regression coefficients of the model of economic attitudes

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|||

|

ЭА4 |

← |

F1 |

1.000 |

|||

|

ЭА5 |

← |

F1 |

0.714 |

0.058 |

12.225 |

*** |

|

ЭА2 |

← |

F1 |

0.957 |

0.078 |

12.244 |

*** |

|

ЭА15 |

← |

F2 |

1.000 |

|||

|

ЭА12 |

← |

F2 |

1.489 |

0.123 |

12.057 |

*** |

|

ЭА17 |

← |

F2 |

1.292 |

0.108 |

11.918 |

*** |

|

ЭА14 |

← |

F2 |

0.648 |

0.084 |

7.698 |

*** |

|

ЭА11 |

← |

F3 |

1.000 |

|||

|

ЭА18 |

← |

F3 |

0.599 |

0.061 |

9.798 |

*** |

|

ЭА3 |

← |

F3 |

0.732 |

0.071 |

10.320 |

*** |

|

ЭА13 |

← |

F4 |

1.000 |

|||

|

ЭА16 |

← |

F4 |

0.964 |

0.122 |

7.910 |

*** |

|

ЭА21 |

← |

F4 |

1.279 |

0.175 |

7.330 |

*** |

Note: ЭА2 — consumer satisfaction, ЭА3 — the desire to save, ЭА4 — confidence in the future thanks to savings, ЭА5 — financial literacy, ЭА11 — the value of independent economic decisions, ЭА12 — economic ambitions, ЭА13 — negative attitude to entrepreneurs, ЭА14 — activity in the real estate sector, ЭА15 — financial optimism, ЭА16 — the priority of earnings over vocation, ЭА18 — awareness of consumer irrationality, ЭА21 — the priority of earnings over health.

CMIN=312,865; df=40; p=,000; CFI=,948; RMSEA=,070; GFI=,964; Pcose=,000

Figure 4. The model of the relationship between psychological time and economic attitudes

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”

Table 6

Regression coefficients of the model of the relationship between psychological time and economic attitudes

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|||

|

ОБ |

← |

НЭ |

1.000 |

|||

|

ОН |

← |

НЭ |

0.949 |

0.027 |

35.428 |

*** |

|

ОП |

← |

НЭ |

0.760 |

0.025 |

30.751 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

НК |

1.000 |

|||

|

ФН |

← |

НК |

1.075 |

0.043 |

25.053 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

НК |

0.473 |

0.028 |

16.690 |

*** |

|

ПП |

← |

ПК |

1.000 |

|||

|

Б |

← |

ПК |

0.886 |

0.048 |

18.528 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

ПК |

0.637 |

0.040 |

15.964 |

*** |

|

UG |

← |

ПК |

0.222 |

0.047 |

4.711 |

*** |

|

ОА |

← |

НЭ |

–0.147 |

0.018 |

–8.066 |

*** |

|

DS |

← |

НК |

0.217 |

0.039 |

5.628 |

*** |

|

DS |

← |

НЭ |

–0.135 |

0.020 |

–6.886 |

*** |

|

NP |

← |

НК |

0.441 |

0.038 |

11.719 |

*** |

|

NP |

← |

НЭ |

0.092 |

0.018 |

4.982 |

*** |

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — negative-cognitive component, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”.

orientation (balanced time perspective) contributes to the formation of positive economic attitudes — confidence in the future and satisfaction with consumer opportunities due to financial knowledge.

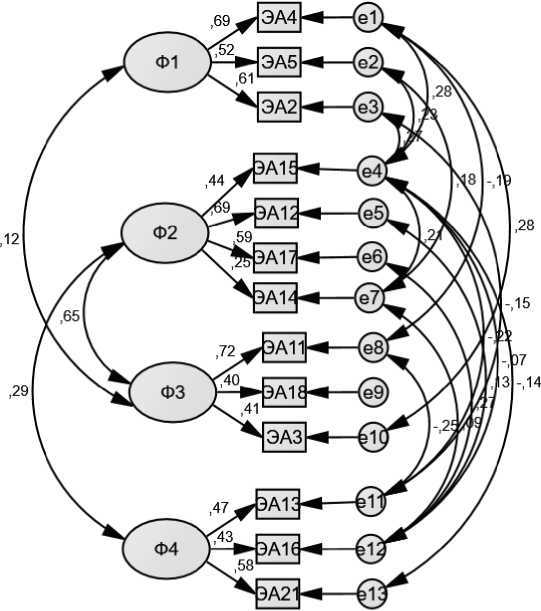

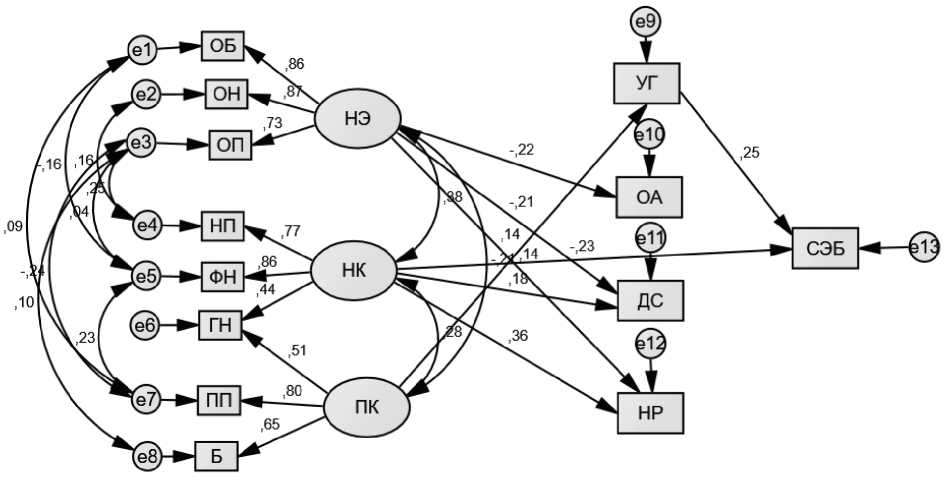

Further, an indicator of subjective economic well-being was added to the empirical model, calculated as a subjective assessment of income level. As a hypothesis, it was suggested that the components of psychological time, both directly and indirectly, affect the feeling of subjective well-being in the economic sphere. As can be seen in Figure 5, the a posteriori model confirmed its validity: CMIN = 356.799; df = 50; p = 0.000; GFI = 0.963; CFI = 0.944; RMSEA = 0.066, Pclose = 0.000; while maintaining the statistical reliability of the regression coefficients (Table 7).

The empirical model confirms the hypothesis about the impact of the components of psychological time on the level of subjective economic well-being, both directly and indirectly, through economic attitudes. In particular, the escapist time orientation contributes to the reduction of the level of subjective economic

well-being. Focusing on past mistakes and failures, combined with a lack of self-confidence to change the situation, contributes to a decrease in satisfaction with the personal economic situation. On the contrary, the harmonious time orientation helps to increase the level of subjective economic well-being indirectly — through the shaping of the future confidence based on financial literacy. Thus, the assumption that the components of psychological time, both directly and indirectly, affect subjective well-being in the economic sphere has been confirmed.

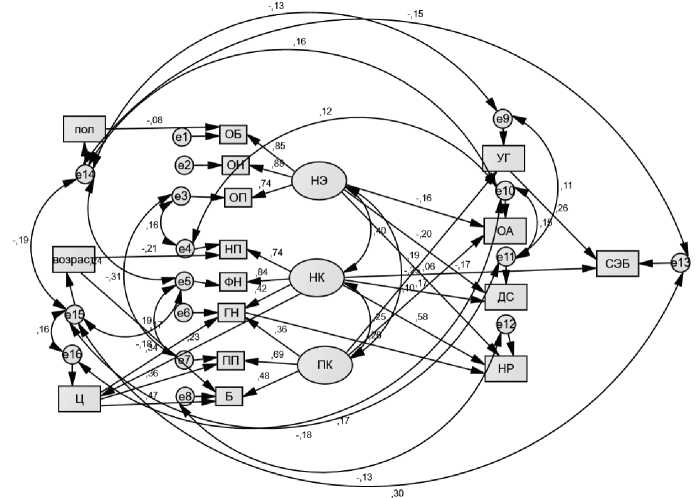

At the final stage of the study, the empirical model, according to the theoretical one, included demographic variables (gender 1-male, 2-female and age), as well as an indicator of life values, which formed a single factor during factorization. The final a posteriori model shows high consent indices (even better than in previous models), which indicates a high level of consistency with the theoretical model: CMIN = 319.607; df = 74; p = 0.000; GFI = 0.972; CFI = 0.964; RMSEA = 0.049, Pclose = 0.660 (Figure 6).

Table 7

Regression coefficients of the model of the impact of psychological time on subjective economic well-being

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|||

|

УГ |

← |

ПК |

0.223 |

0.047 |

4.723 |

*** |

|

ОБ |

← |

НЭ |

1.000 |

|||

|

ОН |

← |

НЭ |

0.953 |

0.027 |

35.498 |

*** |

|

ОП |

← |

НЭ |

0.763 |

0.025 |

30.818 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

НК |

1.000 |

|||

|

ФН |

← |

НК |

1.036 |

0.040 |

25.747 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

НК |

0.465 |

0.028 |

16.719 |

*** |

|

ПП |

← |

ПК |

1.000 |

|||

|

Б |

← |

ПК |

0.889 |

0.048 |

18.525 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

ПК |

0.635 |

0.040 |

15.906 |

*** |

|

ОА |

← |

НЭ |

–0.146 |

0.018 |

–7.996 |

*** |

|

ДС |

← |

НК |

0.223 |

0.038 |

5.825 |

*** |

|

ДС |

← |

НЭ |

–0.137 |

0.020 |

–6,933 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

НК |

0.440 |

0.037 |

11.827 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

НЭ |

0.091 |

0.019 |

4.892 |

*** |

|

СЭБ |

← |

УГ |

0.368 |

0.037 |

10.057 |

*** |

|

СЭБ |

← |

НК |

–0.444 |

0.054 |

–8.264 |

*** |

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”, СЭБ — subjective economic well-being (subjective income level)

All regression coefficients and model relationships are statistically significant (Table 8).

In addition to the previously identified relationships between the components of psychological time, economic attitudes and subjective economic well-being, the contribution of gender (R = –0.26, p = 0.000) to the formation of the depreciating type of psychological time and economic attitudes through the attitude to the future was revealed. Women are more optimistic about the future than men, which specifically affects the emotional component of psychological time. It is also possible to observe the impact of age on the cognitive component of psychological time (in its positive and negative content), and through it — on the economic representations, emotions, motives and subjective economic well-being. With the passage of time (growing up and aging), the orientation to the negative past decreases (R = –0.019, p=0.000), which, in

turn, contributes to an increase in satisfaction with their economic situation. There is also a small contribution of age (R = 0.015 p = 0.000) to the shaping of the future orientation (it increases in adulthood), which in turn affects positive economic attitudes and, as a result, increases the level of subjective economic well-being. However, in general, it can be noted that the impact of demographic variables in the presented model is rather weak.

Much more significant is the impact of life values as the indicator of the motivational and value sphere of an individual, the expression of the striving for something subjectively important [33]. The more pronounced the motivational orientation of a person, the more he or she tends to appreciate the present moment, to take everything that life offers (R = 0.24, p = 0.000); the more often he or she turns to good, bright memories and positive emotions of the past

CMIN=356,799; df=50; p=,000; CFI=,944; RMSEA=,066; GFI=,963; Pcose=,000

Figure 5. Model of the impact of psychological time on subjective economic well-being

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”, СЭБ — subjective economic well-being (subjective income level)

CMIN=319,607; df=74; p= 000; CFI=,964; RMSEA=,049; GFI=,972; Pcose=,660

Figure 6. The final a posteriori model of the relationship between psychological time and economic attitudes Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”, СЭБ — subjective economic well-being (subjective income level), Ц — values, возраст — age, пол — gender

Table 8

Regression coefficients of the final a posteriori model of the relationship between psychological time and economic attitudes

|

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|||

|

Ц |

← |

НК |

0.362 |

0.046 |

7.805 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

НК |

0.482 |

0.029 |

16.542 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

ПК |

0.517 |

0.045 |

11,506 |

*** |

|

UG |

← |

ПК |

0.341 |

0.058 |

5.903 |

*** |

|

ГН |

← |

Ц |

0.239 |

0.015 |

15.932 |

*** |

|

ОБ |

← |

НЭ |

1.000 |

|||

|

ОН |

← |

НЭ |

0.973 |

0.027 |

35.761 |

*** |

|

ОП |

← |

НЭ |

0.776 |

0.025 |

30.816 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

НК |

1.000 |

|||

|

ФН |

← |

НК |

1.063 |

0.040 |

26.885 |

*** |

|

ПП |

← |

ПК |

1.000 |

|||

|

Б |

← |

ПК |

0.770 |

0.056 |

13.754 |

*** |

|

ОА |

← |

НЭ |

–0.107 |

0.019 |

–5.751 |

*** |

|

DS |

← |

НК |

0.212 |

0.040 |

5.275 |

*** |

|

DS |

← |

НЭ |

–0.126 |

0.020 |

–6.357 |

*** |

|

NP |

← |

НК |

0.748 |

0.056 |

13.461 |

*** |

|

NP |

← |

НЭ |

0.037 |

0.019 |

1.919 |

0.055 |

|

СЭБ |

← |

UG |

0.369 |

0.035 |

10.571 |

*** |

|

СЭБ |

← |

НК |

–0.352 |

0.055 |

–6.451 |

*** |

|

ОА |

← |

ПК |

0.167 |

0.052 |

3.190 |

0.001 |

|

NP |

← |

ГН |

–0.291 |

0.038 |

–7.587 |

*** |

|

Б |

← |

Ц |

0.363 |

0.017 |

20.908 |

*** |

|

Б |

← |

age |

0.015 |

0.002 |

8.769 |

*** |

|

ПП |

← |

Ц |

0.252 |

0.016 |

15.609 |

*** |

|

НП |

← |

age |

–0.019 |

0.002 |

–10.107 |

*** |

|

ОБ |

← |

gender |

–0.258 |

0.052 |

–4.952 |

*** |

Note: НЭ — depreciating orientation, НК — escapist orientation, ПК — harmonious orientation, OБ — attitude to the future, ОН — attitude to the present, ОП — attitude to the past, ПН — negative past, ФН — fatalistic present, ГН — hedonistic present, ПП — positive past, Б — future, УГ — confidence and satisfaction in the economic sphere based on financial literacy, OA — financial optimism based on ambitions and striving for status, ДС — the value of independent achievements based on savings, НР — the attitudes of the “employee”, СЭБ — subjective economic well-being (subjective income level), Ц — values

(R = 0.25, p = 0.000); the more he or she tends to set goals and manage the future (R=0.36 p=0.000). In fact, we can make the point about a significant contribution of the expression of human motives, aspirations, and ideals to the formation of a balanced time perspective, and through it — to the shaping of the

positive attitudes in the economic sphere and to subjective economic well-being.

Discussion

The conducted research allowed us to develop a holistic theoretical model of the relationship of psy-

chological time and economic mind, and to verify it. The analysis of the individual elements of the model is consistent with the results of earlier studies.

Thus, the developed model confirms and clarifies the influence of not only social and cultural, but personal values [1] on the perception of time by a person. In particular, the most positive contribution of life values as the most pronounced motivational orientations is fixed in a harmonious time orientation.

Age has been found to be associated with a scale of past negative: as a person matures and ages, negative memories are erased and replaced with more positive ones, which is also consistent with earlier data [35]. The study also found that gender plays a role in relation to time [35]. In particular, women have more positive expectations for the future.

The results of the study convincingly demonstrate the relationship of some elements of psychological time and the subjective perception of income, both directly and indirectly, through economic attitudes. The relationship between psychological time and income has already been demonstrated in a number of studies [30], but in the developed model this relationship has been clarified and specified.

The influence of harmonious type of psychological time on subjective economic well-being, including through the formation of confidence in the economic sphere on the basis of financial literacy, concretizes the idea of a balanced time perspective on well-being [6].

The data on the relationship between psychological time and economic mind should be considered new facts revealed in the study. Depreciating and escapist time orientation are actively involved in shaping economic attitudes that determine less productive strategies of economic behavior. The depreciating orien-

tation decreases the focus on the use of both active and passive economic strategies (saving, investing), as well as the level of claims in the field of economics and the level of financial optimism. Moreover, the negative emotional perception, as well as escapist orientation, reinforces the attitudes of the “hired worker”. Besides, the escapist orientation contributes to the shaping of a savings mindset.

Conclusion

The study contributes to understanding of the importance of the perception and experience of time in the economic life for the formation of one’s well-being in this sphere. Data on the relationship between psychological time and economic mind, partially corroborated by previous studies, expand the understanding of psychological time as an important internal resource in economic life. In particular, an important conclusion is the observation that a balanced time perspective (harmonious type) is directly and indirectly, through economic mind, influencing the growth of subjective economic well-being.

The study is limited to one region and requires testing of the results from other regions and countries. It can already be assumed that there are cultural features of psychological time (for example, the cyclicality and linearity of time perception as a factor of the focus on economic achievement), but it is likely that a balanced time perspective is a universal psychological mechanism that enhances subjective economic well-being regardless of cultural affiliation. The question remains how this model will work in particular social groups, such as those in difficult economic situations. Besides, the contribution of psychological time to economic expectations should be studied further. These challenges present directions of the further research.

Список литературы Psychological time and economic attitudes: testing the theoretical model

- Abulkhanova KA., Berezina TN. Vremya lichnosti i vremya zhizni [Personal time and time of life]. St. Petersburg, Aleteya; 2001. (In Russ.).

- Antonides G, Van Der Sar NL. Individual expectations, risk perception and preferences in relation to in- vestment decision making. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1990;11(2):227-245. (In Russ.).

- Bergadaa MM. The role of time in the action of the consumer. Journal of Consumer Research. 1990;17(3):289-302.

- Bird BJ. The operation of intentions in time:The emergence of the new venture.EntrepreneurshipTheory and Practice. 1992;17(1):11-20.

- Bluedorn AC. Time and organizational culture. In: Handbook of organizational culture and climate. Ed. by N. Ashkanasy, C. Wilderon, M. Peterson. Thousand Oaks, Sage; 2000. Pp. 231–267.

- Boniwell I, Osin E, Linley A, Ivanchenko GV. A question of balance: Time perspective and well-being in British and Russian samples. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2010;5(1):24-40.

- Carmo RM, Cantante F, Alves NA. Time projections: Youth and precarious employment. Time & Society. 2014;23(3):337-357.

- Goodin R, Rice J, Bittman M, Saunders S. The time-pressure illusion: discretionary time vs free time. Social Indicators Research. 2005;73(1):43-70.

- Deyneka OS. Ekonomicheskaya psihologiya [Economic psychology]. St. Petersburg, Saint-Petersburg State University Publishing; 1999. (In Russ.).

- Deyneka OS, Zabelina EV. The results of the development of a scale multifactorial questionnaire for express-diagnostics of economic attitudes. Psychological research, 2018;11(58):9. (In Russ.).

- Drobysheva TV, Zhuravlev AL. Sistema faktorov ekonomicheskogo soznaniya v usloviyah vtorichnoj ekonomicheskoj socializacii lichnosti i gruppy [System of factors of economic consciousness in the secondary economic socialization of the personality and group]. Institute of psychology Russian Academy of Sciences. Social and economic psychology, 2016;1(2). (In Russ.).

- Emelyanova TP, Drobysheva TV. Obraz budushchego blagosostoyaniya v obydennom soznanii rossiyan [Image of future well-being in the ordinary consciousness of Russians]. Psychological Journal. 2013;34(5);16- 32. (In Russ.).

- Furey JT, Fortunato VJ. The theory of MindTime. Cosmology. 2014;18:119-130.

- Furnham A, Henikou A. Correlational and Factor Analytic Study of Four Questionnaire Measures of Organizational Culture. Human Relations. 1996;49(3):349-371.

- Furnham A. Why Do People Save? Attitudes to, and Habits of Saving Money in Britain. Journal of Ap- plied Social Psychology. 1985;15(5):354-373.

- Golovaha EI, Kronik AL. Psihologicheskoe vremya lichnosti [Psychological time of personality]. Kiev, Naukova Dumka; 1984. (In Russ.).

- Grant SJ. Perspectives in Time: How Consumers Think About the Future. Consumer Research. 2003;30(1):143-145.

- Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Psychology and Culture. 2011;2(1-8):1-26.

- Holman RH, Silver. The Imagination of the Future: A Hidden Concept in the Study of Consumer Deci- sion Making. In: Advances in Consumer Research. Ed. by K. B. Monroe, A. Arbor. 1980. Vol. 8. Pp. 187–191.

- Nestik TA. Social’no-psihologicheskaya determinaciya gruppovogo otnosheniya k vremeni [Socio-psychological determination of the group attitude to time. Thesis]. Moscow, 2015. (In Russ.).

- Kalil A, Schweingruber HA, Seefeldt KS. Correlates of Employment Among Welfare Recipients: Do Psychological Characteristics and Attitudes Matter? American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29(5):701- 723.

- Klos A, Weber EU, Weber M. Investment Decisions and Time Horizon: Risk Perception and Risk Behavior in Repeated Gambles. Management Science. 2005;51(12):1777-1790.

- Kurnosova S, Zabelina E. Attitudes towards time at international migrants. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences. 2018;39.

- Khashchenko VA. Sub”ektivnoe ekonomicheskoe blagopoluchie i ego izmerenie: postroenie oprosnika i ego validizaciya [Subjective economic well-being and its measurement: constructing and validating a ques- tionnaire]. Experimental psychology. 2011;4(1):106-127. (In Russ.).

- Kovalev VI. Kategoriya vremeni v psihologii (lichnostnyj aspekt) [The category of time in psychology (personal aspect)]. In: Categories of materialistic dialectics in psychology. Ed. L. I. Antsyferova. Moscow, Sci- ence; 1988. Pp. 216–230. (In Russ.).

- Lebedeva NM. Bazovye cennosti russkih na rubezhe XXI veka [Basic values of Russians at the turn of the XXI century]. Psychological journal. 2000;21(3):73-87. (In Russ.).

- Mewse AJ, Lea SEG, Wrapson W. First steps out of debt. Attitudes and social identity as predictors of contact by debtors with creditors. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2010;31(6):1021-1034.

- MuzdybaevK.Perezhivanievremenivperiodkrizisov[Experiencingtimeduringcrises].Psychological Journal. 1999;21(4):5-21. (In Russ.).

- Nuttin J. Motivaciya, dejstvie i perspektiva budushchego [Motivation, Action and Prospect for the Fu- ture]. Ed. DA Leontiev. Moscow, Smysl; 2004. (In Russ.).

- Padawer EA, Jacobs-Lawson JM, Hershey DA. Thomas Demographic D. G. Indicators as Predictors of Future Time Perspective. Current psychology. 2007;26(2):102-108.

- Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 1966;80(1):1-28.

- SeijtsGH.The importance of future time perspective in theories of work motivation. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 1998;132:154-168.

- Schwartz S, Butenko T, Sedova D, Lipatova A. Refined theory of basic individual values: application in Russia. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 2012;9(2):43-70.

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1995;67(6):1063-1078.

- SircovaA,FonsJR.vandeVijver,OsinE.[etal.]Agloballookattime:A24-countrystudyoftheequiv- alence of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory. SAGE Open, 2014;1:1-12.

- Shipp AJ, Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: The subjective experience of the past, present, and future. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2009;110(1):1-22.

- Webster JD, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Time to flourish: The relationship of temporal perspective to well-being and wisdom across adulthood. Aging and Mental Health, 2014;18(8):1046-1056.

- Weismann J. Vremeni v obrez: uskorenie zhizni pri cifrovom kapitalizme [Time is short: acceleration of life under digital capitalism]. Moscow, Delo; 2019. (In Russ.)

- Zabelina E, Tsiring D, Chestyunina Yu. Personal helplessness and self-reliance as the predictors of small business development in Russia: Pilot research results. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2017;14:279-293.

- Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1999;77(6):1271-1288.

- Zhuravlev AL, Kupreychenko AB. Nravstvenno-psihologicheskaya regulyaciya ekonomicheskoj aktivnosti [Moral and psychological regulation of economic activity]. Moscow, Institute of Psychology, RAS; 2003. (In Russ.).