Radiocarbon chronology of the Bronze Age Fedorovka culture (new data relevant to an earlier problem)

Автор: Epimakhov A.V., Alaeva I.P.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article presents the results of excavations and dating of the Fedorovka culture cemetery of Zvyagino-1 in the Southern Trans-Urals. It consists of 12 small kurgans, each of which contains from one to three differently arranged graves with cremations. The funerary items include typical Fedorovka clay vessels. We estimated the age of bones of domestic animals found on the area under the kurgan or in graves. The new dates were compared with those generated previously. Statistical analysis has made it possible to assess the time range as being from the mid-18th to mid-15th centuries cal BC (medians of calibrated intervals). Dates of the Alakul-Fedorovka complexes fall in the same time range, illustrating the process of interaction between these two traditions. The results of modeling were compared with the dates of the Andronovo sites in Kazakhstan, the Baraba forest-steppe, and Southern Siberia. The dates were similar, barring those of the more ancient series from Kazakhstan. Dates for the Alakul sites in the Trans-Urals were earlier (19th to 16th centuries cal BC), documenting the long coexistence of the Alakul and Fedorovka traditions. In the Southern Trans-Urals, the former tradition appears to have declined earlier. The question as to whether the Fedorovka tradition survived until the Cordoned (Valikovaya) Ware cultures remains open due to the lack of dates for the Cherkaskul culture, which resembles Fedorovka, while being stratigraphically earlier than the Cordoned Ware cultures.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146973

IDR: 145146973 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.2.055-064

Текст научной статьи Radiocarbon chronology of the Bronze Age Fedorovka culture (new data relevant to an earlier problem)

The issue of the relationship between the main cultures of the Andronovo community has been actively discussed since the time of their identification. The Southern TransUrals is a key region for the discussion, due to research at eponymous sites in this part of Northern Eurasia. This has led to attempts to extend cultural and chronological findings over a vast territory, including Central and Eastern Kazakhstan. The original model proposed by

K.V. Salnikov (1967: 340–351) was adjusted many times, especially in terms of the relationship between the Alakul and Fedorovka traditions. A detailed analysis of arguments for parallel or sequential existence of these cultures is beyond the scope of this article. Ultimately, the issue rests upon the interpretation of the syncretic Alakul-Fedorovka complexes, which are viewed either as evidence of interaction between different population groups (Kuzmina, 1994: 21–22, 32), or as an intermediate link in transformation from one culture to another.

The supporters of a sequential relationship agree in recognizing the Fedorovka antiquities as originating in later periods (Zdanovich, 1988: 167; Matveev, 1998: 377– 378; and others).

The most obvious solution to this endless discussion is to establish the chronological positions of each culture at the level of its region and entire community. Previous efforts have not yet led to generally accepted results. One of the reasons is the extreme paucity of dates for the Fedorovka sites, especially since they have not been actively studied in recent years. Moreover, even though the Fedorovka and Alakul traditions have been well differentiated by the funerary rite, their distinction in research of settlements is problematic.

This study presents new field evidence and radiocarbon dates that have a reliable context. Its objectives are to analyze these dates within the available database on the Fedorovka and Alakul cultures, and to compare them with the results of dating Andronovo evidence from other regions.

The history of accumulation of radiocarbon dates for the Fedorovka culture in the Southern Trans-Urals

The first attempts at establishing the chronology of the Fedorovka culture were made in the early days of the radiocarbon dating of archaeological sites. At that stage, scholars focused on obtaining individual dates; large samples were used (mainly of wood). The final

summary for the Andronovo community (Kuzmina, 1994: 372–376) contained relatively few dates (only eight) related to the Fedorovka antiquities of the Urals. Today, cultural attribution of some evidence needs revision. For example, the artifacts from the Novo-Burino and Bolshaya Karabolka cemeteries included recognizable Cherkaskul items, along with those of the Fedorovka culture. It is impossible to rely on this series because of difficulties in determining the context, imperfect methodology, inability to take into account the effect of “old wood”, as well as significant discrepancy of dates in relation to each other and with relation to more modern dating results. This can also be applied to the Alakul dates and other series. This problem is by no means limited to the region under discussion. Detailed analysis of old and new dating results for the sites of the Minusinsk Basin has led to rejection of the former for similar reasons (Polyakov, 2022: 221).

The addition of dates for the Fedorovka antiquities were a result of research at the settlement of Cheremukhovy Kust. Four wood samples were studied by scintillation (Matveev, 1998: 363–368). The variation among conventional values amounted to a thousand years, which is clearly unrealistic for a single site. At least one date (UPI-568, 4250 ± 160 BP) was too early, and had a huge standard deviation for the Bronze Age. It falls into statistical outliers when using the range diagram for the medians of calibrated values (see below). There are no formal reasons for excluding the other dates. The discrepancy in the results may exist for many reasons (Bronk Ramsey, 2008), including, as is the case in our discussion, the effect of “old wood”, problems associated with selection and storage, and cultural identification of the samples. The pottery complex of the settlement is considered by the authors to be of a single culture, although some of the vessels do not correspond to standard Fedorovka pottery.

Currently, the spread of accelerator measurement technologies has enabled the series of dates of the Fedorovka and Alakul-Fedorovka antiquities of the Urals to be expanded as a result of international projects (Hanks, Epimakhov, Renfrew, 2007; Panyushkina, 2013; Schreiber, 2021) that are focused on establishing a chronological system of the region (Trans-Urals) or microregion (Lisakovsk) (Fig. 1). At the microregional level, it was possible to greatly increase the accuracy

Fig. 1 . Location of the Fedorovka and Alakul-Fedorovka sites with the available 14C dates.

a – Fedorovka sites; b – Alakul-Fedorovka sites. 1 – Cheremukhovy Kust settlement; 2 – Urefty I cemetery; 3 – Zvyagino-1 cemetery;

4 – Kamennaya Rechka III settlement; 5 – Solntse-Talika cemetery; 6 , 7 – Lisakovskiy I and III cemeteries.

of age determinations for the Alakul sites using the method of coordinating variations or wiggle matching, and establish the internal chronology of the complexes. It has been reliably proven that the Alakul traditions were earlier than the Alakul-Fedorovka traditions in this microregion. Unfortunately, the Fedorovka complexes were dated only using calcined human bones, whereas the relative chronology of the microregion was based on spatial distribution data.

Systematic studies of Andronovo sites in the Baraba forest-steppe (Molodin et al., 2012; Molodin, Epimakhov, Marchenko, 2014) and Minusinsk Basin (Polyakov, 2022: 219–226) have provided a large series of dates. The position of the Andronovo antiquities in periodization systems has been reliably established and expressed in numbers. The Kazakhstan part of the dates is uneven; new dates mainly result from projects aimed at studying the paleogenome of humans and animals. This vast region has a series of only slightly over a hundred dates from all periods of the Bronze Age mostly from its southern and eastern parts. In addition, it is problematic to correlate many dates with a specific culture.

Results of excavations at the Zvyagino-1 cemetery

The Zvyagino-1 kurgan cemetery is located on a high terrace on the left bank of the Koelga River (tributary of the Uvelka River in the Tobol River basin) in Chebarkulsky District of the Chelyabinsk Region. Twelve mounds with a height of 0.3–1.0 m and 7–16 m in diameter were identified. Ten objects were studied during excavations under the supervision of I.P. Alaeva in 2017–2022. Round and oval-shaped kurgans had soil mounds. In four cases, stone enclosures were made on the areas under the mounds (Fig. 2, 2 ). Burial structures (up to three under a single mound) included ground pits (sometimes with traces of a wooden cover or walls lined with stone) and stone boxes (Fig. 3, 1 ) oriented along the west–east line. In several cases, animal sacrifices were discovered within the enclosures at the level of the virgin soil (cattle and small ruminants). For example, a complex of sacrifices in kurgan 7 was represented by a cattle skull with a mandible lying on four bones of distal limbs. The head and lower part of the animal’s legs were apparently used in the ritual.

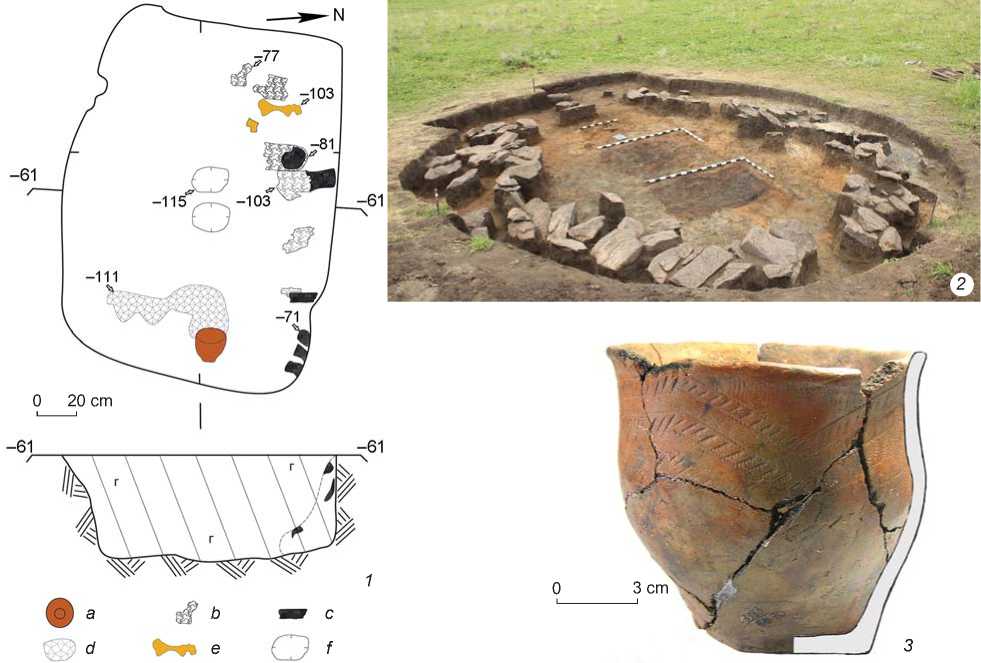

Fig. 2 . Plan view and cross-section of burial 1, kurgan 7 at the Zvyagino-1 cemetery ( 1 ), area of the kurgan ( 2 ) and ceramic vessel from it ( 3 ).

a – ceramic vessel; b – birch bark; c – charcoal; d – cremation; e – pelvic bone of a horse; f – post pit.

2 0 3 cm

Fig. 3 . Burial 1, kurgan 1 at Zvyagino-1 ( 1 ) and ceramic vessel from it ( 2 ).

Thirteen burials were examined. Almost all showed traces of robbery. The burials were made according to the rite of secondary cremation. The remains of the funerary meal in the graves included horse ribs, as well as cattle and horse pelvic bones (see Fig. 2, 1; 4, 1). Burial goods included pot-shaped pottery (from one to three vessels per burial) and clay dishes in two cases. Bronze temple pendants twisted 1.5 times (one with remains of gold foil) were found in two pits.

Specific features of the funerary rite (stone enclosures and boxes, cremation, orientation of graves along the west–east line), and distinctive pottery (see Fig. 2, 3 ; 3, 2 ; 4, 2 ) have made it possible to attribute all of these kurgans to the Fedorovka culture of the Southern Trans-Urals.

0 20 cm

0 3 cm

II

Fig. 4 . Plan view and cross-section of burial 2, kurgan 2 at Zvyagino-1 ( 1 ) and ceramic vessel from it ( 2 ). a – ceramic vessel; b – cremation; c – animal bones.

9Хтт-ггТТГ111 @ а

\ \ \ \ b

^Ч?%\^ ад c

Results of dating

Animal bones (of horse and cattle) and a tooth were selected for dating from the complexes of sacrifices and burials in three kurgans. Collagen was extracted and other stages of sample preparation were performed at the “Laboratory of Radiocarbon Dating and Electron Microscopy” Center for Collective Use at the Institute of Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Measurements were carried out at the Center for Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia (USA). The results were analyzed using accelerator mass-spectrometry (AMS), with determination of the amount of collagen, and the isotope ratio of nitrogen and carbon. Calibration was carried out using the OxCal 4.4.4 software (Bronk

Ramsey, 2017) and calibration curve IntCal20 (Reimer et al., 2020). Statistical outliers were identified using a box-and-whisker plot of the medians of calibrated values. Summing up the probabilities of calibrated values was used to analyze the degree of homogeneity among the samples. The boundary procedure was used to establish the boundaries of the date interval. The new data were added to the Table summarizing dating results (Table 1).

In assessing the reliability of the new data, the current authors proceeded from an analysis of possible distortions, checking the internal consistency of dates and their compatibility with previously obtained ones. Material evidence for producing the new series of dates excluded the freshwater reservoir effect. The amount of extracted collagen was over 1 %, which was sufficient

Table 1. Results of radiocarbon dating of the Fedorovka and Alakul-Fedorovka sites in the Southern Trans-Urals

|

Site |

Complex |

Index |

Evidence |

Conventional date, BP |

Source |

|

Fedorovka |

|||||

|

Cheremukhovy Kust, settlement |

Dwelling 1, pit 2 |

UPI-568 |

Wood |

4250 ± 160 |

(Zakh, 1995) |

|

ʺ |

Dwelling 2, pit 1 |

UPI-560 |

ʺ |

3446 ± 95 |

(Ibid.) |

|

ʺ |

Dwelling 6, pit 2 |

UPI-564 |

ʺ |

3280 ± 30 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

ʺ |

UPI-569 |

ʺ |

3605 ± 53 |

ʺ |

|

Urefty I, cemetery |

Kurgan 16, burial 1 |

OxA-12521 |

Bone (horse) |

3440 ± 30 |

(Hanks, Epimakhov, Renfrew, 2007) |

|

Zvyagino-1, cemetery |

Kurgan 1, burial 1 |

IGAN AMS -9091 |

ʺ |

3390 ± 30 |

This article |

|

ʺ |

Kurgan 2, burial 2 |

IGAN AMS -9092 |

Bone (cattle) |

3300 ± 25 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

Kurgan 7, burial 1 |

IGAN AMS -9093 |

Bone (horse) |

3310 ± 25 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

Kurgan 7, complex of sacrifices |

IGAN AMS -9094 |

Tooth (cattle) |

3415 ± 25 |

ʺ |

|

Lisakovskiy I, cemetery |

Enclosure 3, burial 1 |

Poz-93398 |

Calcined bone (human) |

3280 ± 35 |

(Schreiber, 2021) |

|

ʺ |

Enclosure 9, burial 1 |

Poz-93400 |

ʺ |

3230 ± 35 |

(Ibid.) |

|

ʺ |

Enclosure 11, burial 1 |

Poz-93401 |

ʺ |

3195 ± 35 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

Enclosure 18, burial 1 |

Poz-93402 |

ʺ |

3290 ± 35 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

Enclosure 17, burial 3 |

Poz-93404 |

ʺ |

3410 ± 35 |

ʺ |

|

ʺ |

Enclosure 6, burial 1 |

Poz-93405 |

ʺ |

3255 ± 30 |

ʺ |

|

Alakul-Fedorovka |

|||||

|

Urefty I, cemetery |

Kurgan 15, burial 6 |

OxA-12523 |

Bone (horse) |

3345 ± 30 |

(Hanks, Epimakhov, Renfrew, 2007) |

|

ʺ |

Kurgan 30, burial 1 |

Poz-94211 |

Bone (human) |

3390 ± 35 |

(Schreiber, 2021) |

|

Kamennaya Rechka III, settlement |

Dwelling 1 |

OxA-12518 |

Bone (cattle) |

3372 ± 29 |

(Hanks, Epimakhov, Renfrew, 2007) |

|

ʺ |

ʺ |

OxA-12519 |

Bone (animal) |

3341 ± 29 |

(Ibid.) |

|

Solntse-Talika, cemetery |

Kurgan 6, burial 1 |

OxA-12520 |

Bone (cattle) |

3347 ± 29 |

ʺ |

|

Lisakovskiy III, cemetery |

Structure 2 |

AA-78389 |

Wood |

3414 ± 40 |

(Panyushkina, 2013) |

Note. Bold font indicates the statistical outlier.

for reliable measurements (Table 2). The ratio of nitrogen and carbon was in the normal range (2.9–3.6). The most noticeable differences were in the composition of nitrogen isotopes (δ15N), which does not appear to be related to the species of herbivorous domestic animals nor to the sample type. There was probably some difference in the composition of their food. However, the values are in the range of indicators typical of herbivores of the steppe Trans-Urals (Hanks et al., 2018; Svyatko et al., 2022).

One date for the Zvyagino-1 cemetery, obtained from a tooth from the complex of sacrifices in kurgan 7 (IGANAMS-9094, 3415 ± 25 BP) was reliably earlier than the others. There was a second, later date for that kurgan. The difference in the medians was over a hundred years. Nevertheless, the early sample does not look extraneous with relation to the combined series. Based on the reliability of the results, one must assume that the ritual of sacrifice preceded the funerary ceremony, which means that the kurgan area remained without a mound for quite a long time.

In terms of absolute values, the new results are close to those obtained earlier (see Table 1). The summation of probabilities forms an asymmetrical figure shifted towards later dates, although their number is insufficient to make confident conclusions. Determining the boundaries has made it possible to obtain an idea as to the interval of the entire group: 19th–15th centuries BC (by medians). However, the earliest (UPI-569, 3605 ± ± 53 BP) and the latest (UPI-564, 3280 ± 30 BP) dates are not statistically consistent with the series. For this reason, a calculation was made for the dates obtained by means of accelerator technologies. The medians of the modeled boundary intervals delineate the period of 1742–1451 BC (Table 3).

Calculation of interval boundaries for the Alakul-Fedorovka dates (1728–1589 BC based on the medians) has shown that it entirely fit the formed Fedorovka interval, being closer to its early part. Combining the dates of the Fedorovka and the syncretic Alakul-Fedorovka sites did not really change the interval boundaries.

Table 2. Results of analyzing radiocarbon dates of the Zvyagino-1 cemetery and composition of stable isotopes

|

IGAN AMS |

Collagen, % |

C/N at |

δ15N, ‰ |

δ¹³C, ‰ |

14C-date (1σ), BP |

Calibrated date (95.4 %) BC |

Median, BC |

|

9091 |

17.66 |

3.18 |

2.29 |

–20.37 |

3390 ± 30 |

1863–1564 |

1675 |

|

9092 |

9.24 |

3.21 |

2.48 |

–20.88 |

3300 ± 25 |

1618–1510 |

1567 |

|

9093 |

12.22 |

3.18 |

5.24 |

–20.27 |

3310 ± 25 |

1624–1510 |

1574 |

|

9094 |

6.19 |

3.17 |

5.42 |

–19.84 |

3415 ± 25 |

1867–1625 |

1706 |

Table 3. Modeling of the results of radiocarbon dating of the Fedorovka sites in the Southern Trans-Urals

|

Index |

Calibrated date, BC |

|||||

|

without modeling |

modeled |

|||||

|

68.3 % |

95.4 % |

Median |

68.3 % |

95.4 % |

Median |

|

|

OxA-12521 |

1871–1689 |

1879–1632 |

1746 |

1758–1689 |

1781–1641 |

1716 |

|

Poz-93404 |

1744–1632 |

1874–1615 |

1700 |

1736–1672 |

1750–1637 |

1696 |

|

IGAN AMS -9094 |

1746–1641 |

1867–1625 |

1706 |

1700–1636 |

1727–1626 |

1674 |

|

IGAN AMS -9091 |

1736–1626 |

1863–1564 |

1675 |

1661–1619 |

1696–1610 |

1642 |

|

IGAN AMS -9093 |

1612–1538 |

1624–1510 |

1574 |

1621–1585 |

1631–1550 |

1603 |

|

IGAN AMS -9092 |

1611–1532 |

1618–1510 |

1567 |

1606–1556 |

1614–1535 |

1580 |

|

Poz-93402 |

1609–1511 |

1631–1456 |

1559 |

1580–1527 |

1600–1516 |

1553 |

|

Poz-93398 |

1609–1505 |

1623–1455 |

1547 |

1545–1510 |

1581–1502 |

1531 |

|

Poz-93405 |

1541–1457 |

1612–1446 |

1516 |

1529–1501 |

1545–1465 |

1514 |

|

Poz-93400 |

1518–1447 |

1607–1421 |

1488 |

1516–1472 |

1527–1451 |

1497 |

|

Poz-93401 |

1499–1438 |

1518–1410 |

1465 |

1501–1452 |

1509–1425 |

1475 |

|

Boundary – beginning |

– |

– |

– |

1782–1697 |

1854–1648 |

1742 |

|

Boundary – end |

– |

– |

– |

1492–1426 |

1507–1362 |

1451 |

Chronology of the Fedorovka sites in the Trans-Urals

(analysis of diachrony and synchrony)

The new data are in close agreement with earlier conclusions about periodization of the local Bronze Age (Molodin, Epimakhov, Marchenko, 2014) and complements the series of AMS dates. Most samples did not suggest an earlier chronological interval. Against this consistent background, it seems unwise to use the dates obtained in the period from the 1970s to early 1990s. In our sample, the dates of the Alakul-Fedorovka and Fedorovka antiquities belonged to the same chronological range. However, it is necessary to note that a limited series from only a few sites was used. In this regard, the method for verification would be diachronic analysis, including an examination of the chronological relationship between the Alakul and Fedorovka traditions. Unfortunately, the dates of the Alakul tradition remain the subject of debate, at least when compared with the Sintashta and Petrovka series, which are supported by solid findings (Krause et al., 2019; Epimakhov, 2020; and others). Many dates for the Alakul sites were obtained by scintillation; there are some contradictions in the dates for closed complexes, etc. The calibrated values showing the mid-3rd millennium BC raise particular doubts. There is no obvious solution to this problem, since a large number of widely varying dates has been accumulated, and choice between them is often made according to different models of cultural genetic processes (Grigoriev, 2021). In this case, we should be limited to the dates obtained in the 2000s for the steppe and forest-steppe Trans-Urals and the steppe Tobol region (the Urefty I, Kulevchi VI, Stepnoye VII, Lisakovskiy I, III, IV, Troitsk-7, Peschanka-2, Alakul, and Subbotino cemeteries, and the settlement of Mochishche). All of these have been published (Hanks, Epimakhov, Renfrew, 2007; Panyushkina, 2013; Poseleniye…, 2018: 100; Krause et al., 2019; Epimakhov et al., 2021; Schreiber, 2021: 161, 193).

All early dates were obtained for one site (the Mochishche settlement) using scintillation. It is possible that the analysis was carried out during a period of some technological failure in the work of one particular laboratory (Marchenko, 2016: 442). Over a half of the remaining 32 dates were obtained from human bones, while the rest, from wood and animal bones. No statistically significant differences were found between the samples. There were four pairs of different types of samples from closed complexes. In all cases, the values were close, or the dates for human bones were later. The procedure for determining the boundaries provided values within the 19th–16th centuries BC (Table 4).

The inclusion of benzene dates, which some scholars insist on (Grigoriev, 2021: 27), would significantly bring

Table 4. Modeling of the results of radiocarbon dating of the Alakul sites in the Southern Trans-Urals (Epimakhov, 2023)

There is more clarity in establishing the chronological position of the Alakul and Fedorovka cultures based on AMS dating, at least for the Southern Trans-Urals. The Alakul groups appeared earlier than the Fedorovka population; then, there was a fairly long period of their coexistence and interaction. Our series of dates indicates that the Alakul tradition declined somewhat earlier than the Fedorovka tradition. If we focus on the medians, this occurred in the 16th and 15th centuries BC, respectively.

The next stage, well supported by dates, was associated with the Cordoned Ware cultures. The beginning of that stage was reliably dated to the 14th century BC, and only some dates indicate the late 15th century BC (Epimakhov, Petrov, 2021). Apparently, there were no catastrophic events or abandonment of the area; therefore, the chronological gap may be interpreted two ways. First, a well-recognizable, although almost undated set of Cherkaskul antiquities has been identified in the Trans-Urals. Observations on the relative chronology have made it possible to place these artifacts earlier than the Cordoned Ware evidence (Poseleniye…, 2018: 94, 102). Second, the use of median (average) values for analysis could have made some impact. In fact, the intervals during two-sigma calibration are adjacent and the gap is minimal. For selecting the correct answer, a significant expansion of the database on many cultures, including the Fedorovka and Cherkaskul, is required.

The analysis of evidence from the adjacent areas is complicated by uneven distribution of available dates across the regions, frequent absence of thematic summaries (for example, on the Timber-Grave culture of the Volga-Ural region), problems in correlating specific dates with a specific culture, especially in cases where they were published as a part of large projects on paleogenetics (Narasimhan et al., 2019; Librado et al., 2021). The largest and most reliable series are associated with the Baraba forest-steppe and Minusinsk Basin, which are regions remote from the Trans-Urals. A small sample is available for the Fedorovka antiquities of Kazakhstan.

Seven dates of the Kazakhstan sites (Degtyareva et al., 2022: 68) are associated with the central and southern parts of the region, and combining them should be considered with caution. The early dates were obtained from charcoal from the multilayered settlement of Begash. The rest of the dates were obtained from human bones and wood from the burial grounds in Central Kazakhstan. The medians of the boundaries show a long period of 1834–1611 BC, which is obviously more ancient than the Trans-Urals. We should be limited to this statement due to impossibility of verifying the cultural context of finds from the settlement and the likely influence of human diet on dating results.

Numerous data on the Western Siberian foreststeppe were obtained using various techniques and laboratories. Excluding a number of problematic dates, it was possible to compile an interval of calibrated values within the 18th–15th centuries BC (Molodin, Epimakhov, Marchenko, 2014: 149). However, the authors in the summary publication (Reinhold, Marchenko, Molodin, 2020) mentioned the possibility that the dates from human bones were two hundred years older. This means that the boundaries of the chronological interval could be adjusted quite significantly.

Twenty-four dates were obtained from human bones for the Andronovo sites of the Minusinsk Basin, indicating the period of the 17th–15th centuries BC (Polyakov, 2022: 222). A likely problem with these dates is the untested possibility of the reservoir effect. For the previous (Okunev) and subsequent (Karasuk) periods, checking the date consistency for different types of sources did not reveal any significant impact on the final result (Ibid.: 183, 310). Nevertheless, the possibility of the impact of local factors cannot be completely excluded (Svyatko et al., 2022), which mitigates the definitiveness of the conclusions.

The Andronovo antiquities of Siberia are often viewed as resulting from migration of the carriers of the Andronovo tradition to a foreign environment. This applies to both the Baraba forest-steppe and Minusinsk Basin, where migrants encountered the Krotovo and

Okunev populations. This scenario implies a relatively late chronological position of the Andronovo traditions with relation to the Trans-Ural Fedorovka traditions. Comparison with our results does not confirm such a model for the possible reason that the Trans-Ural Fedorovka sites, like the Siberian sites, were not the earliest, and the carriers of these traditions were also a superstratum group, which was incorporated into the Alakul environment and therefore should be considered a subcultural phenomenon (Stefanov, Korochkova, 2006: 126). Furthermore, the problem of locating the origins of the Fedorovka traditions still remains unresolved.

Conclusions

New dating results for the Fedorovka cemetery of Zvyagino-1 expand modern data on this culture. The internal consistency of the dates and their proximity to those previously obtained makes it possible to consider the interval of the 18th–15th centuries BC reliable. The dates of the syncretic Alakul-Fedorovka sites also correspond to the same period and illustrate the time when these two traditions coexisted and interacted. This conclusion does not contradict the previous concepts on periodization of the regional cultures. According to this model, the Alakul culture appeared in the Trans-Urals earlier than the Fedorovka, and they existed in parallel for a long time. Currently available dates indicate the extinction of the Alakul traditions somewhat earlier than the Fedorovka ones. Whether the Fedorovka traditions survived until the Sargary-Alekseyevka period is unclear because of the small number of dates for the Fedorovka sites and almost complete absence of dates for the Cherkaskul culture, which occupies a stratigraphic position in the steppe and southern forest-steppe regions between the Andronovo evidence and the final stage of the Late Bronze Age (late 14th–11th centuries BC).

Comparison with other areas where the Andronovo traditions were found has revealed synchronicity of the sites in the Trans-Urals, Baraba forest-steppe, and Middle Yenisei region. The dates obtained from the TransUrals evidence were definitely not influenced by the reservoir effect, yet other series of dates, most of which were obtained from human remains, are less credible, especially since there have been initial indications that such dates were older.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, Project No. 20-18-00402.