Regional features of the traditional clothing of Ukrainians and Belarusians in the south of the Russian Far East (late 19th to early 20th century)

Автор: Streltsova I.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145471

IDR: 145145471 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.1.140-148

Текст обзорной статьи Regional features of the traditional clothing of Ukrainians and Belarusians in the south of the Russian Far East (late 19th to early 20th century)

Studies of the regional specifics of traditional culture in recently-settled regions cover a wide range of topics associated with various aspects of ethnic traditions, including their stability and alteration. The regional specifics in the clothing of Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers of the colonized areas in the south of the Russian Far East are of special interest. Research into the regional components in the traditional outfits of Ukrainians and Belarusians in Siberia was made by E.F. Fursova (2004, 2011), T.M. Nazartseva (2005), and M.A. Zhigunova (2005). Quite a few studies of traditional clothing on the basis of ethnological materials have been carried out in the Far East and in Primorye. Important data obtained from the studies of the outfits of Ukrainians and Belarusians in Primorye are provided in monographs and field records by Y.V. Argudyaeva (1993, 1997; Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). Interesting information on the shirts of the Eastern Slavic settlers in the Khabarovsk Territory is provided in the catalogue of the Grodekov Khabarovsk Regional Museum (Rubakhi slavyan-pereselentsev…, 2007). Regional specifics of the traditional shirts, female sleeveless jackets (kirsetka),

and waistbands of the Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers were studied on the basis of ethnographic collections owned by the Arseniev State Museum of Primorye (Streltsova, 2012, 2014a, b). However, any comprehensive studies of the regional specifics of the Ukrainian and Belarusian traditional outfits in the south of the Russian Far East have not been carried out so far. This topic is essential for the understanding of regional distinctions in manufacturing techniques, usage and development in clothing traditions of the Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers in Primorye in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The terms designating the garments and their components, as well as methods of decoration, used in the present paper correspond to the generally accepted terms in scientific literature. Some descriptions contain local clothing names that were recorded in interviews with the local people; each case is mentioned in the text.

Transformation of the traditional clothing of Ukrainians and Belarusians in Primorye

The Ukrainian and Belarusian population in Primorye was formed in the course of agrarian colonization of the Russian Far East in the late 19th to early 20th century. Owing to the specifics of the resettlement process in the south of the region, the majority of new settlers came from Left-bank Ukraine, including people from the Chernigov Governorate – 40 %, the Kiev Governorate – 26 %, and the Poltava Governorate – 22 % (Argudyaeva, 1993: 32). Settlers from Belarus arrived in groups mostly from the Mogilev, Grodno, and Minsk Governorates, as well as from the northwestern uyezds of Starodubsky, Novozybkovsky, Surazhsky and Mglinsky of the Chernigov Governorate. In the course of adaptation to a new environment, mutual assimilation of ethnic traditions occurred, which eventually led to the acculturation of the settlers. However, isolation from their native land and compact settlement of the Ukrainians and Belarusians in new areas stipulated a specific conservation of the local traditions of their folk and economic culture; one of the components of this culture was the traditional set of clothing. In Primorye, the set of clothing characteristic of the population of Central and Eastern Ukraine became most typical. The female set included an embroidered shirt, waist clothing (plakhta) or skirt-spidnitsa, sleeveless jacket-kirsetka, and apron. The Belarusian female set mostly resembled that of Mogilev region and the northern uyezds of the Chernigov Governorate. The set consisted of an embroidered shirt, skirt (spadnitsa, andaraka) or skirt with bodice (sayan), and apron. The male set of clothing typical of Ukrainians and Belarusians was universal and included a shirt of hand-made or manufactured fabric and trousers (porty). The traditional male and female clothing sets also included waistbands, headgear, and footwear.

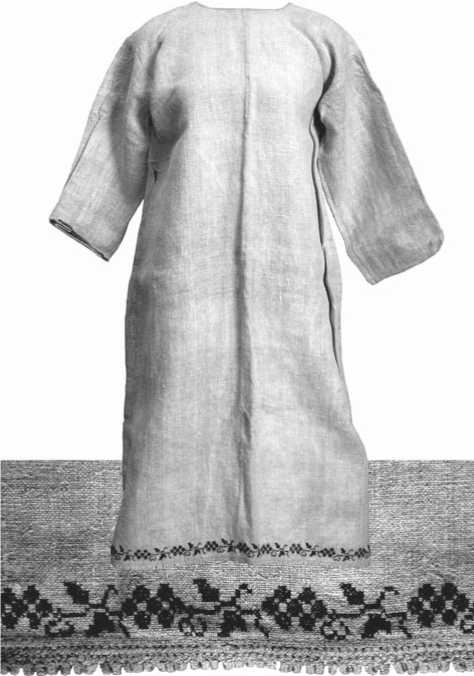

Shirts were the basic item in the Ukrainian and Belarusian female outfit at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries. The shirts in Primorye were sewn either of homemade canvas, hemp fabric or manufactured cotton textile. Hemp was mostly used as the raw material for homemade textiles, because flax yields were often poor (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). In Primorye, the shirts were usually made with straight poliks (rectangular inserts sewn along the weft line). These inserts connected the body parts with the sleeves and provided additional space for free body movements (Zelenin, 1991: 231). The collar and cuffs had close, fine tucks, making the garment loose-fitting and festive. The joint of the top of the sleeve with the insert was often decorated with tucks too. Specimens from the ethnographical collections show an archaic tunic-like design that was also used in Primorye; for instance, a female shirt of a settler from Chernigov from the collection of the Arseniev State Museum of Primorye (MPK 12297 Т4-2885) (Fig. 1). The tunic-like female shirt of the Eastern Slavs in the 19th century is considered to be a relic of the past (Maslova, 1956: 605). This style was noted among the female grave shirts of the Russian Old Believers, as well as in the everyday female outfit in the southwestern provinces of Ukraine (Etnografiya vostochnykh slavyan…, 1987: 267). In Primorye, shirts with one-piece sleeves typical of the Middle Dnieper basin were also recorded (MPK 8727-10 Т 1-179) (Ukraintsy, 2000: 212). In the first third of the 20th century, with the wide spread of industrially produced fabrics, zalakotnitsy shirts with half sleeves (just below the elbow) ending with bell-shaped ruffles with a drawstring became popular (MPK 10278-3 Т1-534; 9144-5 Т1-171). Such shirts were also sewn with yokes (Lobachevskaya, 2009: 36).

In terms of the cut type, female shirts were classified into one-piece items (MPK 17257-1 Т-6237; 3409 Т1-588) and compound items, i.e. made of two horizontal parts: the body ( stan ) and lower part ( podstava ) (MPK 9110-1 Т1-602; 10126-1 Т1-558). The upper ( stan ) part of shirts was usually cut of fine bleached fabric, while the lower part of coarse fabric. With the spread of industrially manufactured cotton fabric, the upper part was made of percale or calico fabrics, while the lower part was made of homemade fabric. Wedding shirts of brides, and female underclothing worn under the plakhta (waist clothing) were made of a single piece of fabric. Hems of such long shirts were exposed and decorated with embroidery, lace, or hemstitch. It is noteworthy that Ukrainians decorated hems not only on festive, but also on casual shirts (Zelenin, 1991: 229).

Fig. 1 . Female shirt. Chernigov Governorate. Canvas, embroidery in the technique of cross-stitch, “drawn thread” decorative seam. Donated by V.Y. Demchenko (born in 1929), a citizen of the Arkhipovka village, Chuguevsky District of the Primorye Territory. MPK 12297-1 Т4-2885.

Female shirts were usually decorated with various ornamental stitches; such stitches decorated the inserts, sleeves, cuffs, collars, shirtfronts, and hems. The following decorative techniques were used both separately and in various combinations: “cutting out”, “pricking out”, satin stitch, chain stitch, embroidery on net, Bulgarian and ordinary cross, and various types of hemstitch. Old stitch types, like “pattern darning” and “holbein stitch”, were rarely used. Decorations were also made with turn-in seam, connecting seam, and the like, serving as an additional element in the ornamentation pattern.

The ornamentation of shirts of the Ukrainian settlers was composed mostly of vegetative and geometric motifs. Belarusian shirts were often decorated with geometric motifs in the form of diamonds, crosses, and eightpetal rosettes. The main color range of the decoration was red with inclusions of black and more rarely dark blue. Residents of some regions of Ukraine and Belarus (predominantly the Chernigov, Poltava, and Gomel regions) used to wear shirts embroidered with white canvas or cotton threads over the white fabric (“white over white” embroidery). Shirts of this type also occurred in Primorye (MPK 9110-1 Т1-602; 17257-1 Т-6237). These were the traditional, bridal wedding clothing, festive outfits of elderly women, and graveclothes (Lobachevsky, 2009: 86) (Fig. 2).

Regional and local distinctions in clothes were observed in the ornament composition. The Chernigov female shirts bore ornaments in the form of horizontal bands on the inserts and upper sleeves (MPK 12297-2 Т4-2884; 9144-4 Т1-591) (Fig. 3). The Chernigov shirts also showed a marked line of connecting-decorative seams on the upper sleeves (MPK 8403-7 Т1-590; 10128-1а Т-5368; 11885-4 Т-2619). This ornamentation technique is represented by the so-called Chernigov broad hem stitch with diamond motif, typical for the local shirts (Ukrainskoye narodnoye iskusstvo…, 1961: 28). The Poltava shirts were usually ornamented with ruffles (plumps) in the upper sleeves, adjacent to the inserts (MPK 9956-2 Т585; 9110-1 Т1-602; 10283-1 Т1-555; 13781-1 Т6-3781) (Nikolaeva, 1988: 172). Embroidery in the form of isolated flower rosettes covered the whole sleeve. The cuffs and collars of the Poltava shirts were usually not ornamented. The female shirts of settlers from Ukrainian Polesye showed ornamented shirt fronts with broad collars and cuffs (Ibid.: 156). The natives from the Mogilev Governorate used to wear shirts with ornamentation bands at the joints of the sleeves with inserts (MPK 9144-8 Т-587) (Lobachevsky, 2009: 19).

The traditional male outfit was not as diverse as the female garments. The basis of the traditional male outfit of Primorye settlers from Ukraine and Belarus was a shirt with a band collar opening from the center (Zelenin, 1991: 224). Male shirts had a straight cut; the upper back part was doubled with linen podopleka (lining) to secure durability. In the early 20th century, the Ukrainian and Belarusian male shirts were hip-long. The shirts were worn over trousers, and were girdled or at a later time belted. Festive shirts were sewn of manufactured, white cotton fabric. The cuffs, collar and front opening were embroidered with red and black threads (MPK 9971-1 Т1-226; 10551-3 Т2-1776).

Ukrainian and Belarusian male half-length clothing consisted of trousers made of homemade canvas fabric. Traditional trousers with comparatively narrow legs (Russ., Belarus. – porty , portki , Ukrain. – portyanitsi , gachi , nogavitsi ) made of homemade white, less common dark blue, coarse cotton fabric ( pestryadina ) were widely used by the Eastern Slavs until the first half of the 20th century (Maslova, 1956: 592). The traditional tapered trousers had two trapezoid-shaped inserts between the pant legs, widening the pant leg (MPK 12297-3 Т 2886). The Belarusian trousers had an additional rhomboid-

Fig. 2 . Female shirt. Mirgorodsky Uyezd, Poltava Governorate. Canvas, embroidery in the “cut out” technique. Hemstitch work, “drawn thread” decorative seam. Donated by V.Y. Usik. MPK 9110-1 Т1-602.

Fig. 3 . Female shirt. Chernigov Governorate. Canvas, embroidery in the “pattern darning” technique. Donated by P.K. Moiseenko (born in 1898) from the Frolovka village, Partizansky District of the Primorye Territory. MPK 9144-4 Т1-591.

shaped piece attached with the pointed corner up, between the legs (MPK 929-6 Т 890). Canvas trousers were used as a summer garment, woolen trousers were worn during the cold season.

Among the Ukrainian settlers, the plakhta (female waist clothing) was popular. This clothing was typical of Ukrainian women in Central and Eastern Ukraine until the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Notably, in Primorye, this type of clothing was not widely used. Plakhta clothing brought from the Ukraine was used only for the first years after resettling (MPK 10282 Т 3505) (Fig. 4). The plakhta was regarded as festive clothing for marriageable girls and married women. It was made of two pieces 1.5–2.0 m long; the pieces were sewn halfway down, the ends of which were folded down over a girdle; it was attached at the waist (Nikolaeva, 1988: 46). Plakhta was made of woolen checkered fabric; the checks bore additional diamond and rosette motifs. The connecting seam on plakhta looked like alternate circles of various colors (Zelenin, 1991: 236) and had both constructive and ornamental functions. The seam was made with woolen threads (worsted work). Red was the dominant color in plakhta .

Skirts became the most popular female waist clothing in Primorye in the early 20th century. Skirts had various names in the Ukrainian and Belarusian traditional clothing (Ukr. – spidnitsa , andarak , kabat ; Belar. – spadnitsa , andarak , sayan ) (Zelenin, 1991: 239). In Primorye, Ukrainian settlers called their skirt the spidnitsa . The Belarusian settlers, for example those born in the village of Petrova Buda of Surazhsky Uyezd, Chernigov Governorate, used to wear homespun sayan skirts (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). In scholarly literature, the term sayan usually designates a Belarusian skirt with attached bodice. The designs of traditional skirts were similar to one another: several widths were sewn together, gathered along the upper edge, and attached to the waistband with fasteners or ties. The main distinctions were the fabrics used (homespun canvas, printed cloth, wool, sateen, and others) and manners of decoration (stitched pleats, sewn-on satin or velvet bands). The skirt length varied from 62 to 88 cm. In Primorye, settlers from Surazhsky Uyezd, Chernigov Governorate, until the 1920s, used to wear skirts made of homespun canvas or woolen cloth, which were dyed dark blue, green, or red (Ibid.). Fabrics were dyed with

Fig. 4 . Plakhta . Chernigov Governorate. Early 20th century, wool, hand weaving. Donated by A.G. Tereshchenko. MPK 10282 Т 3505.

the width of the fabric, aprons were made of one or two pieces. The aprons were usually 15–20 cm shorter than the skirts. Casual aprons were made of dark-colored fabric (homespun casual aprons were dyed dark blue and edged with red bands) (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). Festive aprons were a bright decorative element of the outfit. The aprons were sewn of homespun and industrial white fabrics and trimmed with stitched pleats, embroidery, and lace. The ornamentation was mostly located on the lower parts of the apron in horizontal lines alternated with lace inserts (MPK 11885-9 Т-2624; 10127-5 Т1-550). Lace was attached to the lower edge of the apron; sometimes all the apron edges were decorated with lace (Ibid.). In the early 20th century, the aprons became shorter in correlation with the skirt length, the gap between the apron and the skirt lengths remained unchanged (MPK 11885-9 Т-2624; 10127-5 Т1-550) (Lobachevskaya, 2009: 37).

Women-settlers used to wear sleeveless jackets. This clothing was typical for the Ukrainian women and Belarusian settlers from the northern districts of Chernigov Governorate and the frontier regions close mineral and vegetative dyes. Oak bark produced a dark red color, alder bark a yellowish color, the fruit of the weed named “small birch” produced a dark blue color (Fetisova, 2002: 40).

Another female clothing item popular among the settlers from Chernigov Governorate was a skirt with attached bodice (MPK 10128-2 Т 561) (Fig. 5). Such a garment, which as mentioned above was called a sayan , was typical among the Belarusians, and was likely borrowed from the Baltic nations (Maslova, 1956: 643). This type of skirt was commonly used by the population of the northern part of Chernigov Governorate, and was called a “ spidnitsa do nagrudnika ” (Nikolaeva, 1988: 167). Y.V. Argudyaeva described this clothing item on the basis of interviews with the citizens of the village of Mnogoudobnoye in the Shkotovsky District of the Primorye Territory, natives of Surazhsky Uyezd of the Chernigov Governorate, and designated this piece as a “sarafan” (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). The same name is recorded in the museum catalogues. However, according to G.S. Maslova, this item was called a “sarafan” only by the Russians (1956: 643).

The apron was another item of female waist clothing. In the Ukrainian traditional outfit, aprons represented a transformation of the zapaska skirt—waist clothing consisting of one or two narrow pieces of woolen fabric with ties, which was worn together with the plakhta (Ibid.: 631). The Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers in Primorye wore aprons made mostly of homespun or industrially produced fabrics (percale, chintz, calico) over the skirt or sayan . The upper apron parts were gathered and attached to the waistband. Depending on

Fig. 5 . Sayan . Novgorod-Seversky District of the Chernigov Region. 1930s. Sateen, satin ribbons. Donated by M.F. Skachek from the Galenki village, Oktyabrsky District of the Primorye Territory. MPK 10128-2 Т 561.

to the boundary between the Gomel and Bryansk governorates. This type of sleeveless jacket was named “kirsetka” or “korset” (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). Kirsetka jackets were made of industrially produced fabric: thin cloth, dark-colored sateen, or chintz. Kirsetka jackets were lined and fashioned according to the design and decoration pattern of their Ukrainian parallels.

Regional distinctions were reflected in the design, length, and decoration patterns. For instance, the Poltava kirsetka was quite long (to the knees or lower), with a high waistline fashioned on the back (MPK 9110-6 Т-395). Kirsetka jackets were decorated with applique and trimmed with black velvet or other dark-colored fabric. The Chernigov kirsetka was shorter than the Poltava one, approximately hip-long, and had tucks and pleats on the back (MPK 9120-3 Т234). Women from Chernigov used a decorative machine stitch in ornamenting kirsetka jackets. A slant pocket decorated with applique was made on the right sides of the Chernigov kirsetka jackets (MPK 10126-3 Т 559) (Ukrainskoye narodnoye iskusstvo…, 1961: 28). In Primorye, kirsetka jackets were fashioned by village tailors, who produced the clothing for several neighboring villages (Argudyaeva, 1993: 80). The kirsetka jackets produced in the Spassky District of the Primorye Territory demonstrated a typical style and decoration pattern (MPK 10733-1 Т 1733; 9120-1 Т 552, MPK 16250-1 Т 4818) (Fig. 6). These kirsetka jackets are cut-off at the waist, made of black sateen, lined, with pockets, and decorated with black velvet and a decorative machine stitch.

The Ukrainian and Belarusian outer clothing consisted of the svitka , which was made of felt from white or brown sheep’s wool. The svitka outer garments were cut off at the waist and had two or three pleats ( vusiki ) in the back. Informants said that svitka garments were seldom produced in Primorye, partially because of the poor acclimatization of sheep. The peasants usually wore svitka garments brought from the places of their previous residence (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971).

The ethnographic collections of the Arseniev State Museum of Primorye contain items of female outerwear called the “ yupka ”. These items are designated as “ svitka ” in the museum catalogue, but the Ukrainian and Belarusian svitka garments are outerwear made of woolen cloth (Nikolaeva, 1988: 168). The specimens under discussion are made of industrially manufactured cotton fabric. The discussed items are close to the kirsetka in design and decoration pattern, with the exception of their having long sleeves. The items under discussion are better classified as yupka , because the Ukrainian yupka garments, as opposed to the svitka garments of woolen cloth, were typically made of industrially manufactured canvas, and their style and decoration mostly resembled those of the kirsetka (Ukrainskoye

Fig. 6. Kirsetka . Spassky District of the Primorye Territory. 1920s. Sateen velvet, decorative stitch. Donated by M.A. Krokhina (born in 1910) from the Krasny Kut village, Spassky District of the Primorye

Territory. MPK 10733-1 Т 1733.

narodnoye iskusstvo…, 1961: 27). The analysis of the museum items showed the typical traits of this outer garment. The local yupka varieties were made mostly of black sateen (MPK 9110-7 Т 405, MPK 9110-4 Т 402) or black reps fabric (MPK 18628-4 Т7291); the front was bell-shaped, the back was well-fitted with the aid of tucks and flaring box pleats laid at the waist (Fig. 7). Yupka garments were lined or quilted with padding, decorated with applique of black velvet, decorative buttons, machine embroidery, and buttoned on the left side on buttons or hooks. This type of clothing, brought by settlers from Ukraine, quickly went out of use in Primorye.

The waistband was an accessory of the Ukrainian and Belarusian folk outfit. It combined utilitarian and ritual purposes and represented an invariable part of the clothing of the Eastern Slavs.

In Primorye, waistbands were made of homespun woolen fabric mostly dyed red. Waistbands were either woven, knitted, hand-woven, or woven on a reed frame, using the technique of “weft weaving” (MPK 14011-2 Т 3592), “weaving on a spring” (MPK 11885-1 Т 2616), and others (Lebedeva, 1956: 501). The band’s ends were decorated with fringes from the free ends of the thread (“ makhry ”) or tassels (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). The wedding waistbands were richly decorated; such

Fig. 7. Yupka . Mirgorodsky Uyezd, Poltava Governorate. Early 20th century. Sateen, velvet, applique. Donated by V.Y. Usik. MPK 9110-7 Т 405.

waistbands were often the bride’s wedding present to the groom.

The most popular male headgear were purchased peaked caps and warm caps often lined with padding; fur-caps were less common (Ibid). The traditional Belarusian felt cap ( magerka ) and the Ukrainian cap ( bryl ) were also in use. Unmarried and married women wore various head scarves: homespun or cotton khustki and a woolen shawl ( shalya ) (Ibid.: 116). Married women would wear caps ( chepets )—a head covering in the form of soft cap covering the hair, under their head scarves. The word chepets is common to all Slavic languages; the closest parallels are the Ukrainian ochipok and Belarusian chapets (Maslova, 1956: 684). In Primorye, the name ochipok was commonly used by the settlers (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971). The ochipok cap was the basic headwear of married women in Central and Eastern Ukraine. In Primorye, this sort of cap was worn both by Ukrainian and Belarusian women (MPK 2311-24 Т2743) (Fetisova, 2002: 42).

The characteristic features of these caps are ruffles set over the forehead band ochelye and in the back close to the ties (vzderzhka). Casual caps were made of homespun fabric, cotton or other cheap fabrics. Festive lined caps were made of expensive fabrics. In Primorye, such caps were worn under homemade or manufactured head scarves. Informants from Kharitonovka in the Shkotovsky District of the Primorye Territory said that purchased scarves were seldom used. Homemade head scarves were usually ornamented along the edges, called “banks”, with woven bands, motifs embroidered with red threads, and fringes (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971).

Bast shoes were the basic footwear for settlerpeasants. In the late 19th to early 20th century, bast shoes were typical for Belarusians; Ukrainians from the northern districts of Kiev and Chernigov Governorates also wore bast shoes (Nikolaeva, 1988: 74).

In Primorye, bast shoes were in demand among the Belarusian and Ukrainian settlers, especially during haymaking time, when plenty of bast shoes were purchased (Argudyaeva, 1993: 80). The Belarusian and Ukrainian bast shoes differed from Russian shoes in shape, weaving style, and the material used. The former type was characterized by a straight weaving style of the sole, low sides, and vaguely shaped toe fashioned with long loops, through which a tightening cord or bast was drawn (Zelenin, 1991: 268). In Primorye, as raw materials for bast shoes, settlers used plants that were widespread in the places of their resettlement: lime tree, willow (MPK 4125-5а DR 94), as well as bark of the Manchurian walnut abundant in the Ussuri taiga (MPK 13376-1b DR 2235). Footwear made of rawhide was also in use: postoly , morshni , and ichigi . Ichigi shoes were ordered at a shoemaker or purchased in shops (Argudyaeva, Sem, 1971).

Discussion

This study revealed the regional specificity of the clothing of Ukrainians and Belarusians in Primorye, as well as traced the transformations that took place in the traditional clothing of settlers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Comparison of the results of our research with data on the clothing of Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers in Siberia have made it possible to record the common and distinctive features. During the stated period, in the south of the Russian Far East, as well as in Western Siberia, certain archaic elements still existed in the traditional clothing sets of the Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers. The use of homespun cloth, traditional design, and ornamentation distinguished the clothes of Ukrainians and Belarusians from those of the Russian old resident population. However, despite the settlers’ commitment to their traditional outfits, certain components of clothing, such as the plakhta, svitka, and yupka, quickly went out of use and were not widespread in Primorye. Similar developments were observed in Siberia, where the processes of acculturation and the subsequent abandonment of customary types of clothing were mostly typical in places of Ukrainian and Belarusian settlements dispersed among Russian old residences. In the harsh Siberian climate, the settlers primarily borrowed the off-season and winter clothes of the old residents (Fursova, 2011: 321). Unlike Siberia, where the Russian old resident population prevailed, in the South-Ussuri Region in the early 20th century, the vast majority of old residents and newcomers were Ukrainians (81.26 % of the total number of settlers); the shares of Russians and Belarusians were 8.32 and 6.8 %, respectively (Argudyaeva, 1993: 33). Therefore, the Russian old residents in Primorye could not be regarded as the crucial factor for abandonment of the habitual clothing. In this case, it seems more appropriate to consider the influence of the common urban-style clothing on the peasant style; urban garments gradually replaced the traditional types of clothing owing to the development of trade, distant seasonal work, and other economic factors. The spread of industrially manufactured fabrics and urban clothing style in the first half of the 20th century led to the change of the traditional style, which was equally typical for the settlers in Primorye and Siberia (Fursova, 2011: 320). In the 1920s–1930s, short embroidered shirts with yokes and elbow-long sleeves became very popular. Female canvas shirts and male trousers of the traditional style were gradually transformed into the category of underclothing. The Ukrainian folk plakhtas were replaced by skirts that were decorated with satin ribbons and velvet. The decoration style was also changed mostly owing to simplification of the traditional ornamentation techniques. To sum, the data of the present study mostly coincide with the data collected by Siberian scholars, which suggests a similarity in the processes of usage and transformation of traditional clothing in the areas colonized by the Eastern Slavs.

Conclusions

Research into the regional specifics of the traditional clothing of Ukrainian and Belarusian settlers in Primorye in the late 19th to early 20th century was based on ethnographic collections, archives, and field data. The main conclusion is that the prevalence of settlers from the Chernigov, Kiev, and Poltava governorates led to a wide spread of the traditional clothing of the residents of the Ukraine and Belarus ethno-contact zone over the areas of settlement. Dense settlement of the settlers was among the important factors in accumulation of traditional clothing. Regional specificities have been noted in design, composition, and decoration patterns. In the process of adaptation to the local environment and the new ethno-cultural surroundings, such clothing items as the plakhta, svitka, and yupka, were abandoned. It was partially the result of contacts with old residents, as well as development of a distant seasonal working schedule and eventual borrowing of urban-style clothing. Complex changes in the traditional outfit of Ukrainians and Belarusians migrating to Primorye in the first third of the 20th century were caused by various socio-economic and ethno-cultural factors (development of industrial manufacturing, impacts of the urban culture, and interethnic contacts). In general, the traditional set of clothing of Ukrainians and Belarusians established using the data from Primorye is of scholarly interest, because it demonstrates the extensive stratum of the East Slavic culture, which had a significant impact on the formation and functioning of local traditions.