Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes of Women of Middle and Late Childbearing Age in the Far North (On the Example of the Magadan Oblast)

Автор: Barbaruk Y.V.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 56, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Since the end of the last century, the northern and north-eastern regions of Russia have entered the final stage of demographic transition, in which the birth rate has fallen below the replacement level of generations, and the proportion of the elderly population has increased to its historical maximum against the background of a mass outflow of the working-age population to the central regions of the country. The demographic transition in this territory is heterogeneous and has its own specifics related to the structure of the economy and the nature of employment, migration flows, the historically established settlement pattern, unfavorable climatic and geographical conditions, and patterns of reproductive and consumer behavior. In order to study this specificity, 226 women aged 25-44 were surveyed in Magadan Oblast. The subject of the study was women’s reproductive attitudes, their marital status, focus on having many children, few children or no children, identification of the expected, desired and actual number of children, factors leading to the refusal to have more children, as well as those stimulating childbearing, the problem of distribution of responsibilities in the family. The study has shown that family values are a priority for women of middle and late childbearing age, but they are associated with the demand for improved housing conditions and increased income.

Demographic transition, Far North, reproductive behavior, reproductive attitudes, depopulation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148329543

IDR: 148329543 | УДК: [314:615.256.5](571.65)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2024.56.146

Текст научной статьи Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes of Women of Middle and Late Childbearing Age in the Far North (On the Example of the Magadan Oblast)

DOI:

Currently, the majority of Russian regions are characterized by a narrowed type of reproduction, which results in depopulation and demographic ageing of the population. The regions of the Far North have also faced this problem, but the situation here is not so homogeneous. The territories with a high share of autochthonous and rural population have still preserved the expanded type of reproduction (Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug) or are in the process of transition from the expanded to the narrowed type (Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Sakha Republic). Highly urbanized regions with a predominance of immigrant/Caucasoid population have already switched to a type of reproduction in which the living population does not reproduce its replacement: mortality rates exceed birth rates yearly (Magadan Oblast, Murmansk Oblast, Kamchatka Krai, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Komi Republic, Republic of Karelia). In addition to negative natural and climatic factors, this type of regions is mainly characterized by behavioral factors that aggravate reproductive problems:

-

• negative effects of bad habits [1, Barbaruk Yu.V.; 2, Radhika A.G., Sutapa B.N., Preetha G.S., Sumant S., Jaswinder K., Jagdish K.], often associated with risky sexual behavior in adolescence and early initiation of sexual activity [3, Babenko-Sorokopud I.V.; 4, Ellis B.J., Shakiba N., Adkins D.E., Lester B.M.];

-

• low influence of financial incentives on reproductive attitudes due to high average wages in the northern regions [5, pp. 48–49];

-

• high migration activity of residents of the northern regions, including cyclical migration, associated with shift work. It destroys families and leads to specific family problems [6, Serkin V.P.; 7, Khilazheva G.F.; 8, Sukneva S.A., Barashkova A.S.];

-

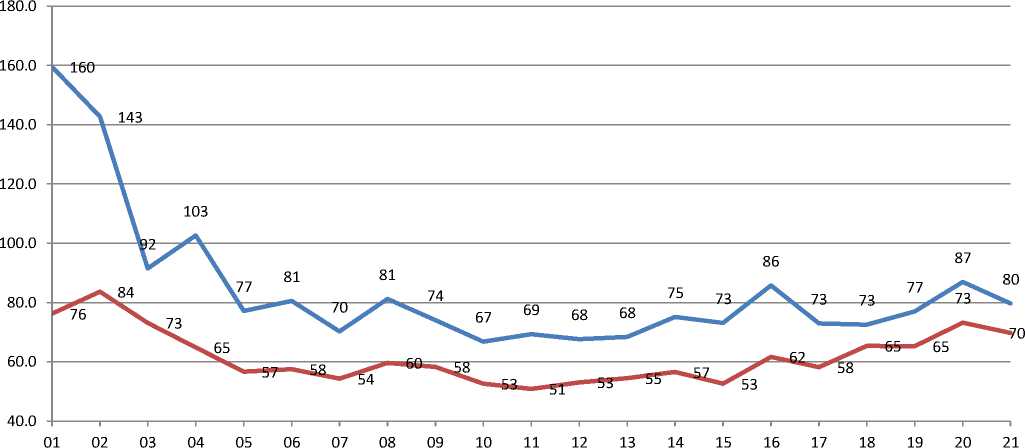

• high level of abortion-contraceptive attitudes. The Far Eastern and Northern regions traditionally occupy leading positions in the number of abortions per 100 births. Magadan Oblast has been a record-breaker in this indicator for decades (Fig. 1);

Fig. 1. Number of abortions per 100 births in the Russian Federation (in red) and Magadan Oblast (in blue) in the period 2012–2020 1

-

• the highest divorce rates among Russian regions (Fig. 2).

-

1 Compiled by the author. Sources: Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System. URL: https://fedstat.ru/indicator/41696 (accessed 28 July 2023); Supplement to the Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2021. Moscow, Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), 2021.

NORTHERN AND ARCTIC SOCIETIES

Yuriy V. Barbaruk. Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes …

Fig. 2. Number of divorces per 100 marriages in Magadan Oblast (in blue) and in the Russian Federation (in red) 2.

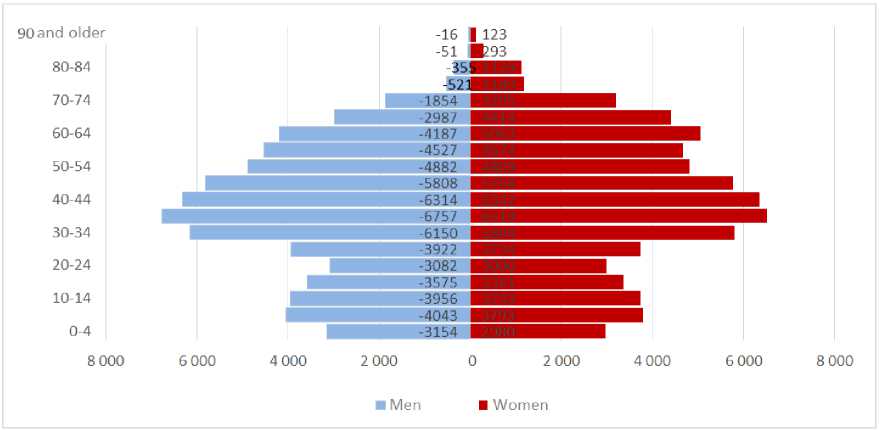

As in most other northern regions with predominantly immigrant population, the most numerous generation here are those born in the late 1970s and 1980s (Fig. 3). This generation has already begun to leave the reproductive age, but due to its large number, it has the greatest reproductive potential for the next decade. The demographic situation in the coming decades will largely depend on the motivation of this generation to have children.

Fig. 3. Age–gender pyramid of the Magadan Region according to the 2020 All-Russian Population Census 3

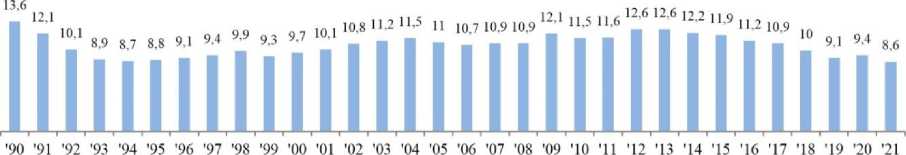

The record negative indicators of natural population growth and the lowest birth rate indicators for the last thirty years can already be observed (Fig. 4). This is happening against the background of the active migration outflow of population from most northern regions of the

-

2 Compiled by the author. Source: Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System. URL: https://www.fedstat.ru/indicator/31604 (accessed 28 July 2023).

-

3 Compiled by the author. Source: Age and gender composition and marital status of the population of the Magadan Oblast. Results of the All-Russian Population Census 2020, Volume 2: Statistical collection. Khabarovskstat. Magadan, 2022.

country that has been ongoing throughout the post-Soviet period. The most intensive outflow during the entire post-Soviet period took place in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug and Magadan Oblast.

Fig. 4. Total fertility rate (number of births per 1000 people) (bottom) and natural population growth rate per 1000 people (top) in the Magadan Oblast from 1990 to 2021 (excluding the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug) 4.

With the continuing trend towards late childbearing [9, Kirilina T.Yu., p. 7], the negative natural population growth will increase until the 2050s and will remain at very high negative values for the next decade and a half.

The aggravation of demographic problems in the region has made the regional executive authorities realize that the interventionist measures of the state in the sphere of population reproduction in the region are not sufficient. As a result, a pilot regional project “Reproductive Health” was approved, the plan of which is designed for 2021–2023 and is aimed primarily at preventing medical and biological problems of reproduction, promoting a healthy lifestyle and forming a positive image of the family.

Materials and methods

The empirical study was conducted using a mass population survey method. The sample type was quota. The survey involved women with established reproductive attitudes aged 25–44. In total, 226 women aged 25–44 were surveyed in the Magadan Oblast in June–August 2022, including 94 respondents aged 25–34 and 132 respondents aged 35–44, which corresponds to the demographic pyramid of the region: women of middle and late reproductive ages predominate.

Research results

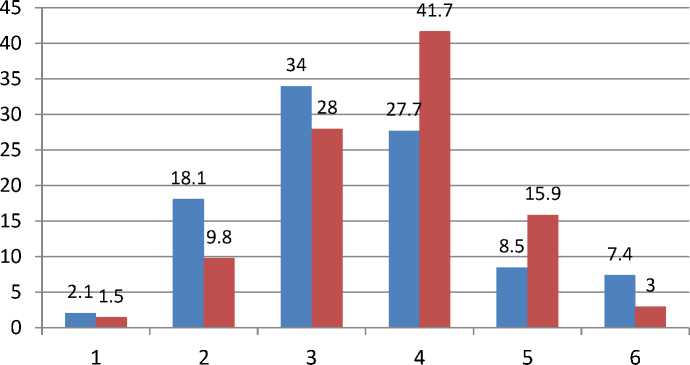

The survey revealed that the modal family size of the women surveyed was four people (Fig. 5). At the same time, for the younger cohort (25–34 years old), this figure was three people. Families consisting of 1–2 people (including the respondent) accounted for 20.2% of the younger cohort and only 11.4% of the older cohort. Households with five or more family members make up 18% for the younger group and 18.9% for the older one.

-

4 Compiled by the author. Sources: Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System. URL: https://fedstat.ru/indicator/31269 (accessed 28 July 2023); Regions of Russia. Socio-economic indicators. 2020. Statistical collection. Rosstat. Moscow, 2020. Regions of Russia. Socio-economic indicators. 2022. Statistical collection. Rosstat. Moscow, 2022; Demographic yearbook of Russia. 2021: Statistical collection. Rosstat. Moscow, 2021.

Fig. 5. Family size of women participating in the survey, %

The marital status of the studied groups of women of reproductive age is given in Table 1.

Table 1

Distribution of responses to the question “Are you married?” 6

|

age cohort, years |

registered marriage |

unregistered marriage / cohabitation |

previously married, not now |

never married |

|

25–34 |

67.0% |

16% |

10.6% |

6.4% |

|

35–44 |

65.2% |

9.1% |

18.9% |

6.8% |

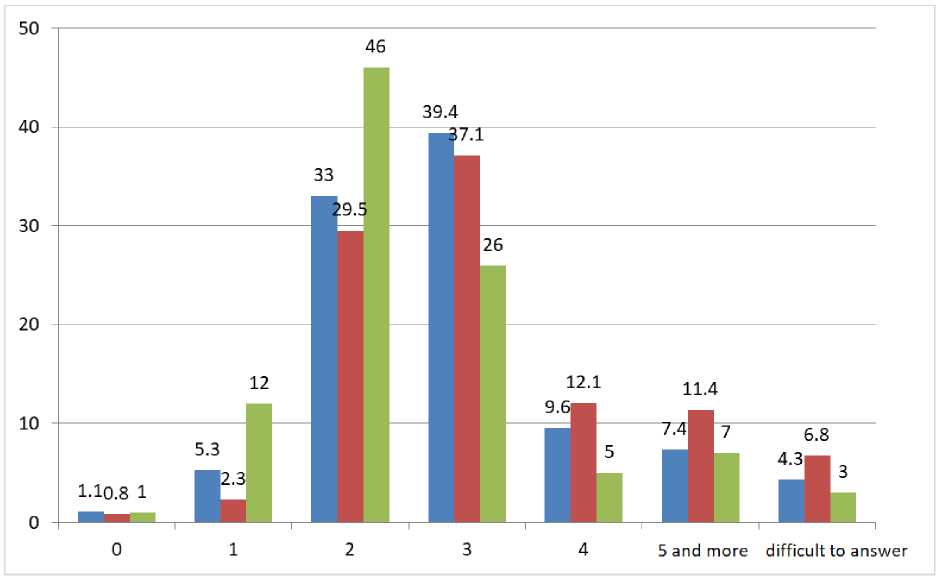

The preferences of the female population with regard to reproductive attitudes are characterized by the indicator of the desired number of children (under the most favorable life circumstances). Two thirds of women aged 25–44 would like to have three or more children under maximally favorable conditions (Fig. 6).

5 Author's calculations.

-

6 Author's calculations.

Fig. 6. Distribution of responses to the question: “How many children in total (including children already born) would you like to have if you had all the necessary conditions?” The answers of women aged 25–34 living in Magadan Oblast are shown in blue, 35–44 years old — in red. The green color represents the distribution of responses to a similar question by women aged 18–45, surveyed during the all-Russian study by LEVADA-CENTER in 2019, % 7

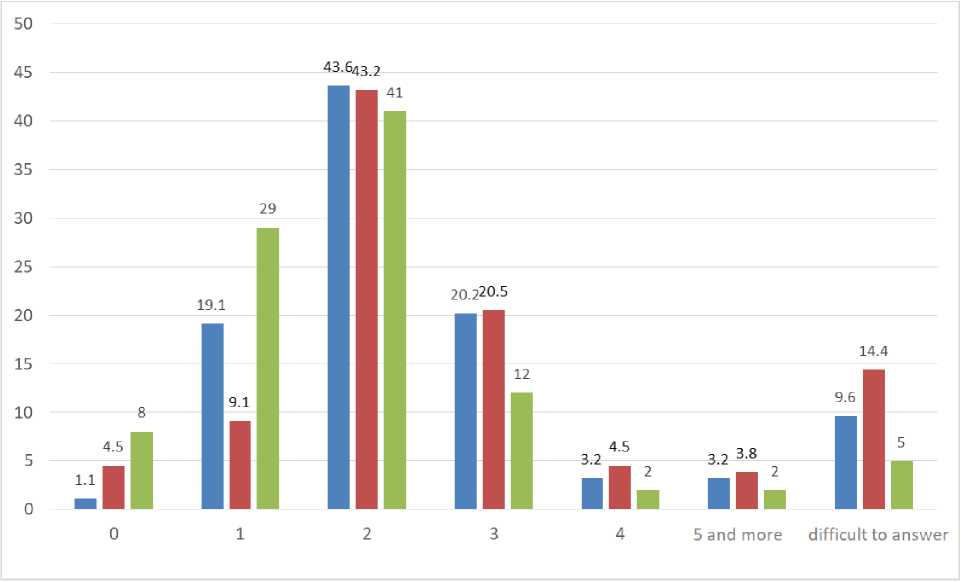

A different situation is shown by the results of responses to the question about the expected number of children — the number of children that respondents plan to have in their family, based on realistically expected life circumstances. In both age categories, women preferred the option of two children, while 19.1% of women in the 25–34 year old cohort expect to have only one child (Fig. 7).

-

7 Compiled by the author. Source: URL: https://www.levada.ru/2019/11/25/zhelaemoe-i-ozhidaemoe-chislo-detej/ (accessed 28 July 2023).

Fig. 7. Distribution of responses to the question: “How many children in total (including children already born) are you going to have?” The answers of women aged 25–34 living in Magadan Oblast are shown in blue, 35–44 years old — in red. The green color represents the distribution of responses to a similar question by women aged 18–45, surveyed during the all-Russian study by LEVADA-CENTER in 2019, % 8

The general trend is that the majority of women of reproductive age over 25 expect to have two children, but in ideal conditions they would like to have three children (Table 2).

Table 2

Desired, expected, and actual number of children among women in the 25–34 and 35–44 year old cohorts (measures of central tendency) 9

|

Desired number of children 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

Expected number of children 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

Actual number of children 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

|

|

Medium |

2.9 / 3.19 |

2.53/ 2.8 |

1.49 / 2.02 |

|

SE |

0.1229 / 0.1108 |

0.1503 / 0.1425 |

0.1067 / 0.0903 |

|

Mode |

3 / 3 |

2 / 2 |

2 / 2 |

|

Median |

3 / 3 |

2/ 2 |

1.5 / 2 |

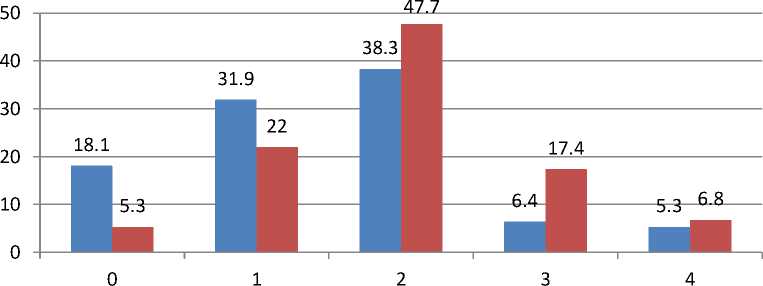

Considering the question of children already born, it should be noted that the modal value for both age cohorts is two children (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Distribution of responses to the question: “How many children have you had in total?” The responses of women aged 25–34 are shown in blue, aged 35–44 — in red, % 10

Among the obstacles to further childbearing, the respondents noted factors of a predominantly economic nature: uncertainty about the future, financial difficulties, lack of housing or impossibility of improving housing conditions to increase the size of the family. In an open-ended question, respondents often noted that financial difficulties would arise precisely after the birth of a child due to the temporary loss of the ability to work of one of the family members. Lack of time, inability to provide childcare and absence of the institution of social nannies are also named as important reasons hindering the birth of children. In both the younger and older cohorts of respondents, health-related concerns should be highlighted: many women either already have health problems that, in their opinion, prevent childbearing, or expect such problems due to pregnancy and postpartum period (Table 3).

Table 3

Distribution of answers to the question “If you would like to have more children than you intend to, what and to what extent prevents you from having the desired number of children?”,% 11

|

Hinder much 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

Hinder 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

Not hinder 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

|

|

Difficulties in family relationships |

11.7/8.3 |

13.8 /11.4 |

74.5 /80.3 |

|

Lack of work |

18.1/22 |

13.8 /9.8 |

68.1 /68.2 |

|

Busy at work |

25.5/25 |

21.3 /21.2 |

53.2 /53.8 |

|

I work far from home, spend a lot of time on the road |

7.4/10.6 |

6.5 /6.1 |

86 /83.3 |

|

Desire to achieve success at work |

11.7/9.8 |

14.9 /22 |

73.4 /68.2 |

|

Financial difficulties |

51.1/53 |

26.6 /20.5 |

22.3 /26.5 |

|

Uncertainty about the future |

46.8/50 |

22.3 /27.3 |

30.9 22.7 |

|

Desire to spend leisure time more interestingly |

5.3/9.1 |

12.8 /12.9 |

81.9 /78 |

|

Desire to properly raise and educate the child (children) already born |

19.1/22 |

24.5 /24.2 |

56.4 /53.8 |

|

Unsatisfactory state of my health |

19.1/17.4 |

21.3 /36.4 |

59.6 /46.2 |

|

Unsatisfactory state of husband’s health |

12.8/6.8 |

20.2 /26.5 |

67 /66.7 |

|

Housing difficulties |

37.2/35.6 |

25.5 /20.5 |

37.2 /43.9 |

|

Fear of infringing on the interests of the children already born |

11.7/8.3 |

24.5 /23.5 |

63.8 /68.2 |

|

Unwillingness of husband |

10.6/9.1 |

9.6 /12.1 |

79.8 /78.8 |

|

Absence of husband |

14.9/20.5 |

6.4 /3.8 |

78.7 /75.8 |

|

It is difficult to place the child in a good nursery or |

12.8/14.4 |

13.8 /13.6 |

73.4 /72 |

|

kindergarten close to home |

|||

|

Inconvenient work schedule |

17/17.4 |

10.6 /13.6 |

72.3 /68.9 |

|

Difficulties in combining work outside the home and at home, I am very tired because of “double working day” |

26.6/28 |

18.1/21.2 |

55.3 /50.8 |

|

No one to leave my child with when I start working |

28.7/34.1 |

21.3/18.9 |

50 /47 |

|

Relatives are against having more children |

6.4/4.5 |

0/2.3 |

93.6 /93.2 |

The birth of children in the family is often viewed as an obstacle to increasing personal/family income. The respondents most often named strengthening of marriage and increased respect from others as the key advantages of having more children in the family. An ambiguous range of opinions was obtained regarding the possibility of improving housing conditions (maternity capital): it may not be enough to improve housing conditions in the regional center. In addition, not every childbirth/adoption is covered by the maternity capital. In general, in the older cohort, respondents more often noted factors that would worsen their lives due to the birth of another child (Table 4). Despite this, the orientation towards having many children in this cohort is higher.

Table 4 Distribution of responses to the question: “If your family had a child (the first one, if you have no children, or another one), how, in your opinion, would it affect ...?”, % 12

|

Help 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

No influence 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

Hinder 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

Hard to say 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

|

|

Increasing your personal income |

17/13.6 |

29.8/37.1 |

28.7/34.1 |

24.5/15.2 |

|

Increasing your family's welfare |

18.1/23 |

36.2/35.6 |

31.9/34.8 |

13.8/12.1 |

|

Maintaining or improving your living conditions |

21.3/18.9 |

37.2/43.2 |

26.6/21.2 |

14.9/16.7 |

|

Your professional development |

10.6/9.8 |

44.7/40.2 |

24.5/32.6 |

20.2/17.4 |

|

Socialising with friends |

9.6/7.6 |

54.3/57.6 |

19.1/21.2 |

17/13.6 |

|

Maintaining good health |

14.9/12.9 |

31.9/28 |

25.5/31.1 |

27.7/28 |

|

Strengthening your marriage |

24.5/25 |

45.7/40.2 |

6.4/6.1 |

23.4/28.8 |

|

Interesting, proper rest |

17/14.4 |

42.6/43.2 |

21.3/27.3 |

19.1/15.2 |

|

Respect from relatives and others |

25.5/17.4 |

45.7/52.3 |

6.4/6.1 |

22.3/24.2 |

As the survey has shown, there are almost no insignificant factors when deciding to have a child (Table 5). The exception, typical for the Magadan Oblast, is the factor of remoteness of work. Almost all settlements in the region are compact. Some discomfort in this regard may be experienced by residents of the suburbs of Magadan and nearby urban-type settlements, who are forced to work in the regional center. High demands of respondents for the quality of medical care and the qualifications of medical personnel are noteworthy. Northern regions, especially remote settlements, often experience a shortage of qualified medical personnel, particularly highly specialized.

Table 5

Distribution of responses to the question “When deciding to have a child (the first one, if you have no children, or another one), to what extent are the following characteristics of living conditions significant for you? “1” means that this characteristic is not significant at all, and “5” means that it is very significant” 13

|

Aspects |

Significance assessment on a 5-point scale, average values 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

|

Possibility of using a work schedule that takes into account the need to care for a small child (flexible hours, part-time work, work from home — remotely) |

4.28 / 4.35 |

|

Distance of work from home, time and resources spent on travelling to and from work |

3.84 / 3.86 |

|

Quality of nurseries and kindergartens (small groups, qualification of educators, nutrition, etc.), their work hours, their accessibility (no queues, low fees) |

4.46 / 4.57 |

|

Quality of work of medical centers for children, their working hours and their accessibility |

4.6 / 4.75 |

|

Availability of own favorable housing to have a child |

4.65 / 4.78 |

|

Work schedule, accessibility, quality of consumer services institutions, stores |

4.18 / 4.21 |

|

Work schedule, accessibility, quality of affordable services of cultural, educational and physical education and sports institutions for children |

4.28 / 4.48 |

|

Work schedule, accessibility, quality of services of family recreation centers |

4.06 / 4.37 |

|

Equal distribution of family responsibilities between wife and husband |

4.26 / 4.23 |

|

Your salary level |

4.71 / 4.7 |

|

Spouse’s salary level |

4.68 / 4.8 |

|

Measures of state support for families with children |

4.4 / 4.55 |

|

Quality of work of medical service centers for pregnant and birthing women, qualifications of medical personnel, provision of modern equipment |

4.65 / 4.7 |

The socio-economic and demographic consequences of the prevalence of one-child families are well known: rapid population ageing, depopulation, “gap” of the intergenerational contract, future problems of pension provision, etc. However, in the minds of respondents, all these problems fade into the background, or are not recognized at all. The problems of an existential nature are more important and significant: potential loneliness of parents in old age or a child without siblings after the death of parents (Table 6).

Table 6 Distribution of responses to the question: “If people know about the following possible consequences of the spread of one-child families, could this affect their intention to have more children?”, % 14

|

Consequences |

rather, will affect 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

rather, will not affect 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

hard to say 25–34 / 35– 44 years old |

there won't be such a consequence 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

|

The share of elderly population will increase significantly, their pension provision will worsen |

14.9/24.2 |

44.7/37.1 |

7.4/10.6 |

33/28 |

|

The traditional national composition of |

19.1/18.9 |

41.5/38.6 |

11.7/15.9 |

27.7/26.5 |

|

the population in the area where you live will change rapidly |

||||

|

Children from one-child families may have problems in the future in relations in their families and upbringing of their children |

20.2/16.7 |

33/34.1 |

24.5/20.5 |

22.3/28.8 |

|

More parents will be lonely in old age, having lost their only child, or he/she will live far from them |

42.6/39.4 |

23.4/28.8 |

13.8/8.3 |

20.2/23.5 |

|

There will be more divorces |

7.4/11.4 |

40.4/38.6 |

22.3/18.9 |

29.8/31.1 |

|

The population of our country will “die out” and Russia will cease to exist |

16/27.3 |

24.5/25.8 |

30.9/18.2 |

28.7/28.8 |

|

Without having siblings, people will feel lonely |

44.7/45.5 |

22.3/24.2 |

14.9/10.6 |

18.1/19.7 |

Life orientations of respondents fit well into the “triangle”, the corners of which are comfortable housing, child raising, and material well-being. At the same time, the focus on material well-being correlates more with a large amount of work than with the focus on entrepreneurship, career growth or advanced training (Table 7).

Table 7 Distribution of responses to the question: “Indicate on a five-point scale how important these goals are for you personally (where “1” is not important at all, and “5” is very important)” 15

|

Significance assessment on a 5-point scale, average values 25–34 / 35–44 years old |

|

|

Own good housing |

4.83/4.81 |

|

Live in a registered marriage with a spouse, own family |

3.79/3.89 |

|

Raise a child |

4.84/4.8 |

|

Work hard, receive a high salary for work |

4.47/4.34 |

|

Material well-being of my family |

4.86/4.83 |

|

Get education, constantly improve qualification |

4.23/4.23 |

|

Have own family business (enterprise, farm, land plot), work only in it, invest money and effort in it, live on the income received from it |

3.23/3.06 |

|

Raise two children |

4.35/4.42 |

|

Career growth |

3.83/3.67 |

|

Spend leisure time in an interesting way |

4.03/4.01 |

|

Socialize a lot with friends |

3.2/3.31 |

|

Have three children |

3.06/3.2 |

|

Be free, independent and do what I want |

2.87/2.92 |

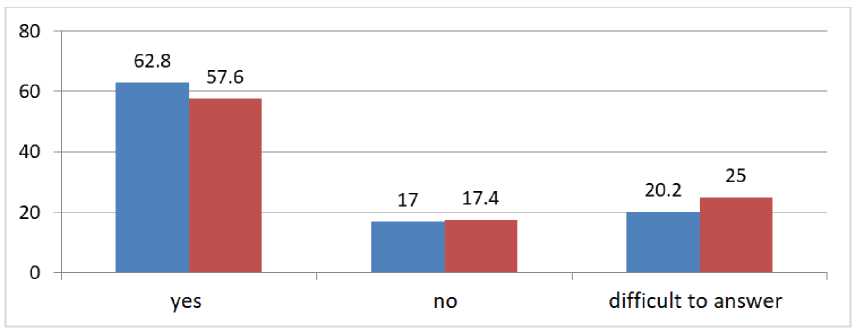

The survey showed that women of reproductive age generally view the issue of a more equal sharing of household responsibilities positively, believing that this would help to increase the birth rate in the country (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Distribution of responses to the question: “If working wives and husbands spent the same amount of time on household chores, would this help to increase the birth rate in Russian families?” The responses of women aged 25– 34 are shown in blue, 35–44 years old — in red, % 16

Conclusion

Despite the difficult socio-economic and natural-climatic conditions, the main reproductive attitudes and key reproductive trends in Magadan Oblast are close to the all-Russian ones. The trend towards a narrowed type of reproduction, formed in the early 1990s, continues to aggravate (Fig. 4) and will become increasingly dramatic as those born in the 1980s leave reproductive age (Fig. 3).

At the same time, there is an obvious tendency for the number of desired children to increase with increasing age of respondents. Thus, the all-Russian population survey on reproductive attitudes by “LEVADA-CENTER” in 2019 covered all women of reproductive age up to 45 years old and revealed a high level of orientation towards having few children among Russian women (Figs. 6 and 7). In our case, the exclusion of women under 25 from the survey shows that the attitude towards having few children is not predominant, at least in Magadan Oblast.

The paradoxical nature of the situation is that the desired number of children is inversely proportional to the physiological capabilities for childbearing. The inevitable accumulation of reproductive problems with increasing age, coinciding with the increase in the desired number of children, maximally actualizes the intensification of work of the health care system to overcome reproductive barriers. This is also noted by the respondents themselves. The availability of qualified medical care and concerns about health when deciding on the next birth are factors that are assessed by respondents as significant when planning a family. This is evident even in the cohort of surveyed women aged 25–34 (Tables 3 and 5).

At the same time, men and women over 35 years old have the greatest reproductive potential in the northern regions in quantitative terms. As the survey has shown, women aged 35– 44 have the most pronounced attitudes towards having many children; they require a more personalized approach in terms of medical and social services, assistance in restoring and maintaining reproductive health for both women and their partners. Efforts should be made to ensure that their desire to start a family is supported by various social institutions and not

Yuriy V. Barbaruk. Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes … undermined by fears of future uncertainties. In this age group, most women already have one or two children, as well as retired parents. Parents of women of late reproductive age may also require additional socio-economic support due to their age, which is a consequence of the trend towards an increasingly later first birth. Thus, instead of support from grandparents, there is an additional factor that restrains childbearing and actualizes the need for a more in-depth approach to the nature of social services to the population (not only in reproductive age). As a woman’s age increases, her reproductive costs increase, and it becomes more efficient to direct her energy towards helping her existing offspring, even if they are few in number. Risks of a woman of late childbearing age increase exponentially and they are transferred to the entire family, as a woman is often a key element in a modern nuclear family; without her, the family may cease to exist. In this context, it is necessary to understand the perception of the majority of interviewed women about the need for more active participation of men in “household chores” to increase attitudes towards having children (Fig. 9).

The survey has shown that family continues to be a priority for women of middle and late reproductive age. The high demand for material values ( better housing conditions, higher earnings) is apparently associated to a greater extent with family, since neither communication with friends, nor active recreation, nor career and status growth, nor freedom in its negative sense are among the respondents’ priorities. In the same way, the fundamental problems of low fertility and low birth rates in the country are perceived in the minds of respondents rather through the prism of the perspective of loneliness of family members, leaving behind political, economic and ethnic aspects.

Thus, the main focus of reproductive policy should be shifted from the reproductive attitudes of the population to the adaptation of the modern urban environment and the work of all social services to new standards, which would allow families of 4-5 people to live as comfortably and safely as possible, and would also minimize critical risks for the family when new members appear. Thus, one of the key problems affecting the gap between the expected and desired number of children is the provision of families with housing. In the Magadan Oblast, the average size of living space, as in Russia as a whole, does not exceed 60 m2, with the social norm of the Housing Code of the Russian Federation for a family of four people is 72 m2 and for a family of five — 90 m2. Developers who satisfy demand in the most marginal areas of housing construction tend to commission more and more small-sized solutions (50 m2 on average in 2021). The question of the legislative status of apartments (without ensuring the housing rights of citizens) also remains open. Thus, market relations in the real estate sector, even taking into account various housing subsidies, tend to lock the modern family within the framework of low fertility or even childlessness for decades to come.

Another equally important aspect that hinders the realization of reproductive attitudes is the current balance between the need to earn money and to care for incapacitated family members. In recent decades, it has been resolved largely through low fertility in favor of

Yuriy V. Barbaruk. Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes … increasing income, but low fertility over time leads to the establishment of a long-term trend in the intensification of the average family’s efforts to care for elderly relatives. This problem is already acute in countries that were the first to make the demographic transition to a narrowed type of reproduction, and it will not be long in coming in our country.

Measures to support fertility, applied today both in Russia and in other countries with similar demographic problems, show low efficiency, although they are extremely important in terms of maintaining the living standards of families with young children [10, Hugo G.; 11, Seo S.H.; 12, Giuntella O., Rotunno L., Stella L.]. This prompts the idea that in order to overcome the existing demographic trends, changes in the system of social relations rather than intensification of economic incentives in the area of fertility are needed.

Список литературы Reproductive Behavior and Reproductive Attitudes of Women of Middle and Late Childbearing Age in the Far North (On the Example of the Magadan Oblast)

- Barbaruk Yu.V. Features of Tobacco Epidemic in the North East of Russia. Russian Pulmonology, 2022, no. 32 (2), pp. 181 188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18093/0869 0189 2022 32 2 181 188

- Radhika A.G., Sutapa B.N., Preetha G.S., Sumant S., Jaswinder K., Jagdish K. Smokeless Tobacco Use and Reproductive Outcomes among Women: A Systematic Review. F1000Research, 2022, vol. 10, art. 1171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.73944.2

- Babenko Sorokopud I.V. Medical and Social Problems of Formation of Reproductive Behavior of Adolescent Girls of Risk Group. Medical and Social Problems of Family, 2021, vol. 26 (1), pp. 59 65.

- Ellis B.J., Shakiba N., Adkins D.E., Lester B.M. Early External Environmental and Internal Health Predictors of Risky Sexual and Aggressive Behavior in Adolescence: An Integrative Approach. Developmental Psychobiology, 2021, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 556 571. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.22029

- Ryazantsev S.V., eds. Demograficheskaya situatsiya v Rossii: novye vyzovy i puti optimizatsii. Natsional'nyy demograficheskiy doklad [Demographic Situation in Russia: New Challenges and Ways of Optimization. National Demographic Report]. Moscow, Ekon Inform Publ., 2019, 80 p. (In Russ.)

- Serkin V.P. Specifics of Family Functions in Conditions of Husband’s Seasonal or Rotating Work. Journal Collection of Scientific Works of KRASEC. The Humanities, 2012, no. 2 (20), pp. 146 154.

- Khilazheva G.F. Modern Family in the Context of Translocal Migration (On the Example of Shift Migrants Families in Bashkortostan). Woman in Russian Society, 2021, no. 1, pp. 68 82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21064/WinRS.2021.1.6

- Sukneva S.A., Barashkova A.S. Influence of Migration on the Matrimonial Suit Dynamics in the Northeast of Russia. Regional Economics: Theory And Practice, 2016, no. 8, pp. 149 163.

- Kirilina T.Yu. Transformation of Reproductive Behavior. Social and Humanitarian Technologies, 2020, no. 4 (16), pp. 3 10.

- Hugo G. Declining Fertility and Policy Intervention in Europe: Some Lessons for Australia? Journal of Population Research, 2012, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 175 198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03029464

- Seo S.H. Low Fertility Trend in the Republic of Korea and the Problems of its Family and Demographic Policy Implementation. Population and Economics, 2019, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 29 35. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.3.e37938

- Giuntella O., Rotunno L., Stella L. Globalization, Fertility, and Marital Behavior in a Lowest Low Fertility Setting. Demography, 2022, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 2135 2159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370 10275366