Scythian age barrows with burials on the ground surface in the Southern Ural steppes: features of the funerary rite

Автор: Myshkin V.N.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The chalcolithic to the middle ages

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145331

IDR: 145145331 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.3.096-105

Текст статьи Scythian age barrows with burials on the ground surface in the Southern Ural steppes: features of the funerary rite

A number of distinctive burial complexes (barrows with burials at the level of the old ground surface) were investigated in the steppe regions of the Southern Urals. Burials on the natural ground or in very small pits in the soil layer were studied by F.D. Nefedov in 1888 in barrow 3 near the village of Preobrazhenka, and in barrows 3 and 4 near the village of Pavlovskaya. However, these sites can hardly be recognized as adequately studied sources, since scholars of that time did not always understand the structure of barrows and might have taken joint burial grounds for burials on the ground surface or on the natural ground (Smirnov, 1964: 82). In 1928, D.I. Nazarov excavated a burial at the level of the ground surface in barrow 7 near the village of Sara (Ibid.). Findings from this barrow have been published in books by K.F. Smirnov and in the corpus of archaeological sources, Savromaty Povolzhya i Yuzhnogo Priuralya (Smirnov, 1961: 17, 82– 84, 102, fig. 2, 5 ; pp. 122–124, fig. 21, A, B; 22, 1–18 ;

p. 147, fig. 45, 1 ; p. 148, fig. 46, 4 ; p. 152, fig. 50, 1–4 ; 1964: 82, 328–329, fig. 35, A, B; Smirnov, Petrenko, 1963: 16, pl. 11, 17 ; 16, 14 ; 18, 15 ; 25, 3 ; 28, 2 , 13 ; 29, 3 , 4 , 7 ). Unfortunately, the map of those excavations has never been published (Fedorov, 2013: 141). The results of the partial excavations of the barrow near the village of Varna, where a burial was also found on the ground surface, have been published in the article of V.S. Stokolos (1962: 23–24). The first comprehensive publication of a fully excavated burial of this type belongs to M.G. Moshkova. The study, presenting the research of burial mounds near the villages of Alandskoye and Novyi Kumak, contains the plan of barrow 1 at the Alandskoye I cemetery, where that burial was discovered, as well as drawings of things and their description. In addition, in her study, Moshkova also pointed to the similarity of that complex to the burial in barrow 7 near the village of Sara, and suggested that the ritual of cremation was a cultural heritage of some groups of the Andronovo population living in the Bronze Age (1961: 119–122). In the corpus Savromaty Povolzhya

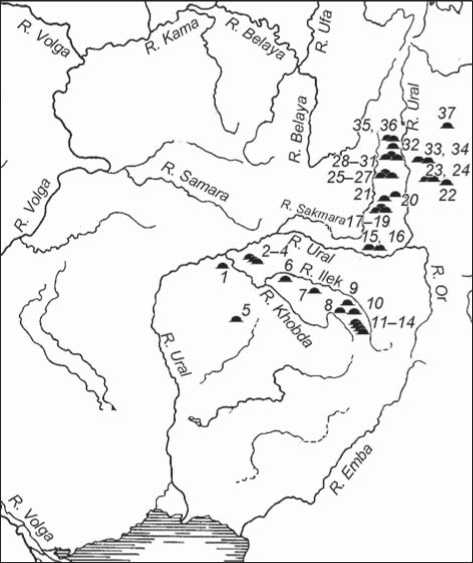

Recently, some materials enriching the source base for the study of burials on the ground surface have been published, which make it possible to conduct a special study of such burial complexes. This article describes the main traditions followed during the burials on the level of the ground surface in the steppes of the Southern Urals, the time of their existence, and specific aspects of their localization. In this article, published data from the excavations of 37 barrows (Fig. 1) is used.

Description of burials at the level of the ground surface

This group of sites is distinguished by the tradition of making burials not in grave pits, typical of the majority of nomadic burials in the barrows of the Scythian time in the Southern Urals, but at the level of the ground surface. The deceased were placed in burial structures of logs, poles, branches, reeds, or sometimes of adobe, which were built above the ground. In many cases, the design of the structures could not be determined due to their poor state of preservation.

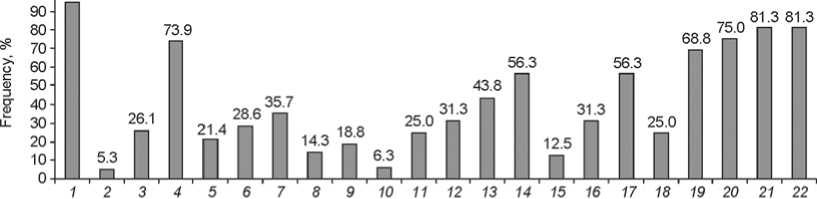

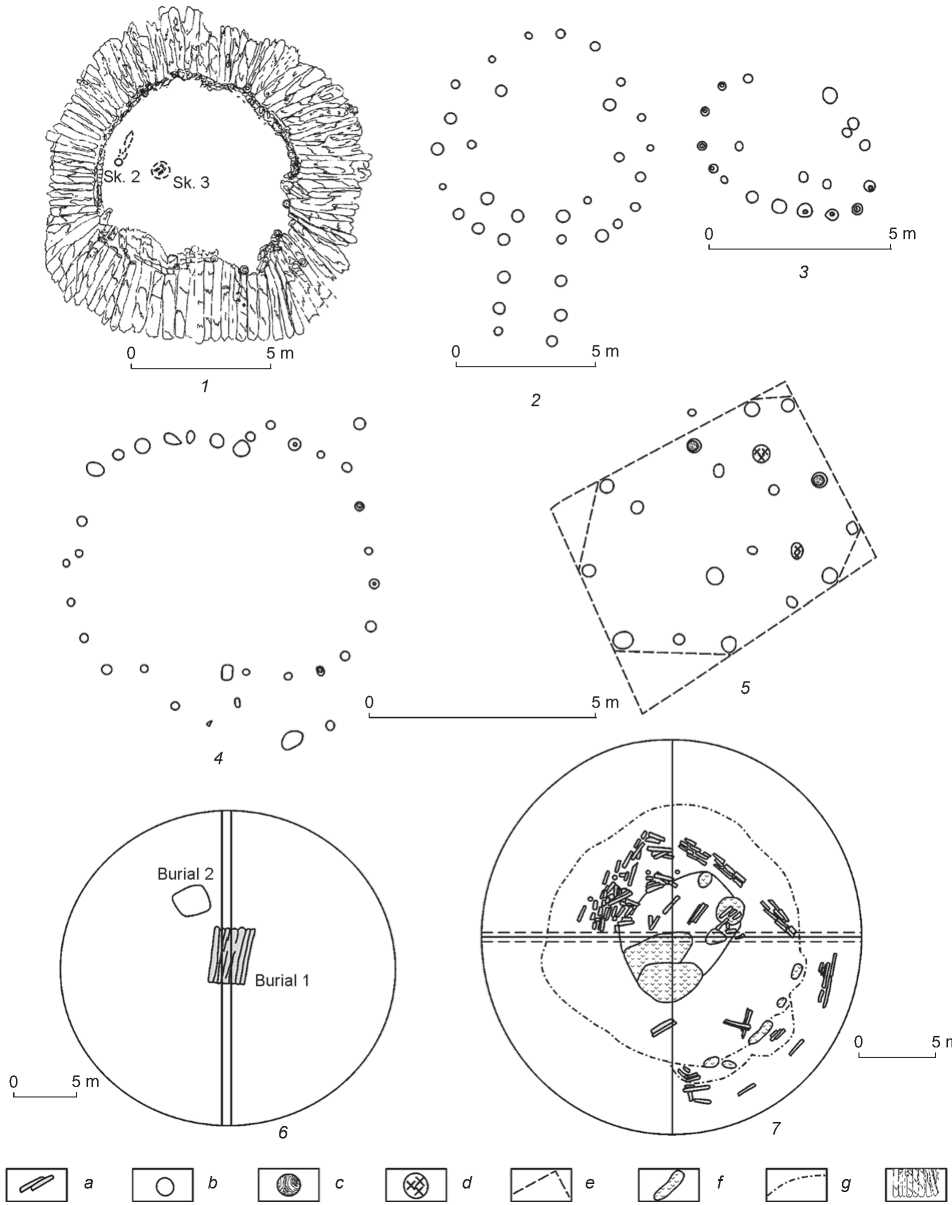

Several varieties of wooden burial structures have been identified (Fig. 2, A). One variety (Fig. 3, 1–4 ) comprises square, rectangular, or octagonal structures in plan view with walls made of logs and fastened by poles which were dug into the ground in pairs on two sides. In some cases, a second perimeter of walls was built inside the outer walls. The structures had flat roofs or covering in the form of a tent. Square structures were oriented with their walls along the four directions; rectangular structures were oriented with their long axis along the lines north–south or west– east with some deviations (Smirnov, 1964: Fig. 17, 1 , 2 ; 1975: 42–43; Pshenichnyuk, 1983: 37–38, pl. XXVIII, 1;

Fig. 1. Location of barrows with burials on the level of the ground surface.

1 – Kyryk-Oba II, barrow 18; 2–4 – Filippovka I, barrow 9, barrow 15, burial 1, barrow 24, burial 1; 5 – Lebedevka VI, barrow 26, burial 1; 6 – Tara-Butak, barrow 3; 7 – Akoba II, barrow 1, burial 1; 8 – Nagornoye, barrow 1; 9 – Zhalgyzoba; 10 – Syntas I, barrow 2; 11–14 – Besoba, barrows 2, 4, 5, 9; 15 , 16 – Sara, barrows 6, 7; 17 – 19 – Perevolochan I, barrows 6–8; 20 – Ivanovka III, barrow 1; 21 – Sagitovo III, barrow 1; 22 – Solonchanka II, barrow 1; 23 – Alandskoye I, barrow 1; 24 – Alandskoye III, barrow 6; 25–27 – Bish-Uba I, barrows 1–3; 28–31 – Sibay II, barrows 12, 13, 17, 19; 32 – Tselinnoye, barrow 1; 33 , 34 – Marovyi Shlyakh, barrows 2, 3; 35 , 36 – Almukhametovo, barrows 8, 14; 37 – barrow near the village of Varna.

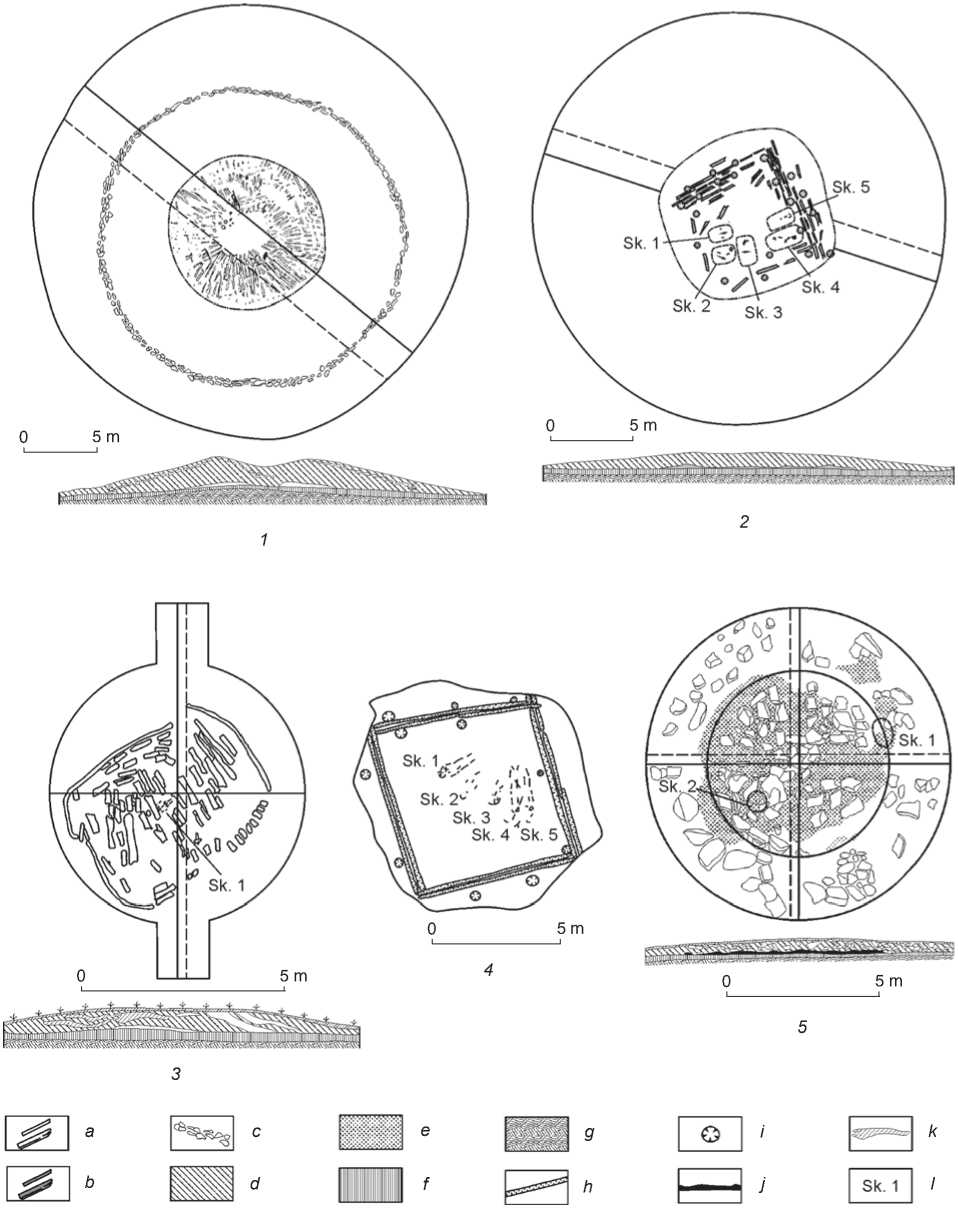

p. 44, fig. 12; pp. 56–57, fig. 14; Kadyrbaev, 1984: 89; Mamedov, Tazhibaeva, 2013: 44, fig. 1, 2 ). The basis of another version of burial structures were poles vertically dug into the ground and held tight by pits which sometimes contained the remains of wood as a filling (Tairov, 2006: 79–87; Morgunova, Kraeva, 2012: 161–163). The poles were placed around the burial area, giving it a round or rectangular shape in plan view. They were installed in one, or sometimes in two rows (Fig. 4, 1–5 ). Walls made of logs were absent. It is possible that the walls could have consisted of bundles of reeds or branches. A covering made of logs rested upon the poles. In one barrow, the covering had the shape of a tent (Fig. 4, 1 ). Burial 1 in barrow 15 of the Filippovka I cemetery was covered by radially placed logs (Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: 143). As a rule, the entrance to the structures was located in the southern and western parts. In some barrows, it was possible to trace the ground entrance corridors formed by parallel rows of vertically dug poles (Fig. 4, 2 ).

100 1 94.7

B

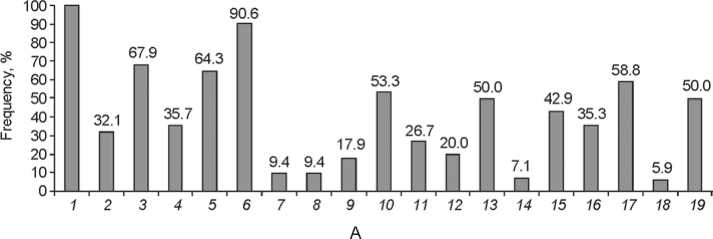

Fig. 2 . Specific features of burials at the level of the ground surface.

A – features related to burial mounds and burial structures: 1 – burial under an individual mound; 2 – height of the mound less than 1.7 m; 3 – height of the mound 1.7 m and more; 4 – diameter of the mound 28 m and more; 5 – diameter of the mound less than 28 m; 6 – earth mound; 7 – stone mound; 8 – surface of the mound covered with stone; 9 – embankment of earth or stone; 10 – cribwork; 11 – pole structure; 12 – floor / platform; 13–15 – covering: 13 – tent-like covering, 14 – imitation of tent-like covering, 15 – flat covering; 16–18 – shape of the structure in the plan: 16 – round/oval, 17 – square/rectangular, 18 – octagonal; 19 – burning of the structure.

B – features characterizing the treatment of the deceased person, the presence of funeral food and accompanying goods: 1 – communal burial; 2 – single burial; 3 – cremation; 4 – inhumation; 5–8 – orientation of the buried people: 5 – to the west, 6 – to the southwest, 7 – to the south, 8 – to the southeast; 9–11 – parts of animal carcasses: 9 – horses, 10 – bovine animals, 11 – sheep; 12 – objects of gold / with gold onlays; 13 – sword; 14 – arrows; 15 – spear; 16 – sword-belt fittings; 17 – horse harness; 18 – altar; 19 – mirror; 20 – personal adornments; 21 – vessels; 22 – other objects.

Burials in barrow 6 at the Alandskoye III cemetery (Fig. 4, 7 ) and in the barrow near the village of Varna, were probably made on platforms rising above the ground (Moshkova, 1972: 62–64; Stokolos, 1962; Tairov, Botalov, 1988: 100, fig. 1), while burial 1 in barrow 26 at the cemetery of Lebedevka VI (Fig. 4, 6 ) was made on a wooden floor (Zhelezchikov, Klepikov, Sergatskov, 2006: 26).

The buried persons in barrow 18 at the Kyryk-Oba II cemetery were placed in a structure made of adobe, which had a covering of logs in the form of tent (Gutsalov, 2010: 58). The burial structure in barrow 6 at the Sara cemetery had a tent-like covering resting upon a circular wall of crude stone plastered by a thick layer of clay (Vasiliev, Fedorov, 1994: 127).

In several burial mounds, the upper soil layer was leveled at the funeral area (Kadyrbaev, 1984: 85, 89; Gutsalov, 2010: 58). There were some instances when the surface of the burial place was coated with liquid clay, sprinkled with chalk (Kadyrbaev, 1984: 85, 89), or was covered with birch bark (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: 57). The funeral platform could be separated from the rest of the space by a small ditch. Some of the buried were placed on beds represented by stretchers (Kadyrbaev, 1984: 89, fig. 3; Mamedov, Tazhibaeva, 2013: 44, fig. 1, 2). The central part of several funerary sites had clay enclosures, square in plan view, which might have imitated hearths. Parts of animal carcasses were laid around or inside such walls. Judging by the calcined surface, coal, and ash, a fire was made in the “hearths” during the funerary rite (Stokolos, 1962: 24; Kadyrbaev, 1984: 86, 88; Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: 143). In one burial, a rectangular structure made of crude stone slabs was found (Kadyrbaev, Kurmankulov, 1977: 105).

A specific feature of the burials under consideration is their collective nature (see Fig. 2, B). A single burial was found only in barrow 3 at the Tara-Butak cemetery (see Fig. 3, 3 ) (Smirnov, 1975: 43). The deceased were placed in an extended supine position in the center of the funerary site, along its perimeter, or near some wall of the burial structure. Sometimes the buried were placed diagonally in the structure (see Fig. 3, 4 ). Cases of orthogonal placement of the deceased have been observed (Kadyrbaev, 1984: 86–89; Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: 143, fig. 1;

Fig. 3 . Plans and sections of barrows with burials at the level of the ground surface.

1 – Almukhametovo, barrow 8 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Fig. 12)); 2 – Sibay II, barrow 17 (after: (Ibid.: Fig. 14)); 3 – Tara-Butak, barrow 3 (after: (Smirnov, Petrenko, 1963: Pl. 1, 3 , 4 )); 4 – Ivanovka III, barrow 1, burial structure (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XXVIII, 1 )); 5 – Alandskoye I, barrow 1 (after: (Moshkova, 1961: Fig. 45)).

a – wood; b – burned wood; c – stones; d – burial mound; e – soil saturated with charcoal, layer of charcoal; f – buried soil; g – native ground; h – ditches; i – holes from the posts; j – soil saturated with charcoal, charcoal layer in the section; k – interlayers of clay or clay loam in the mound; l – skeleton or calcified bone remains of the buried person.

Fig. 4 . Plans of the lower layer of logs of the burial structure ( 1 ), holes from the poles ( 2–5 ), and ground plans of the burial mounds ( 6 , 7 ).

1 , 2 – Akoba II, barrow 1, burial 1 (after: (Morgunova, Kraeva, 2012: Fig. 6, 2 ; 7, 1 )); 3 – Solonchanka II, barrow 1 (after: (Tairov, 2006: Fig. 5, 1 ));

4 – Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 3 (after: (Ibid.: Fig. 3, 1 )); 5 – Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 2 (after: (Ibid.: Fig. 8, 1 )); 6 – Lebedevka VI, barrow 26 (after: (Zhelezchikov, Klepikov, Sergatskov, 2006: Fig. 56, 2 )); 7 – Alandskoye III, barrow 6 (after: (Moshkova, 1972: Fig. 6, 1 )).

a – burned wood of the structure or floor; b–d – holes from the poles ( c – with fragments of wood, d – with charcoal); e – reconstructed structure boundaries; f – areas of the most intense burning of fire; g – borders of the calcined part of the ground; h – wood of the structure.

h

Gutsalov, 2004: Pl. 7, 5 ). The orientation of the heads of the buried towards the south is prevalent; a western orientation has also been found (see Fig. 2, B). A stable tradition was the burning of burial structures (Moshkova, 1961: 119; 1972: 62–64, fig. 6; Kadyrbaev, Kurmankulov, 1976: 148; Pshenichnyuk, 1983: 33–34, 56–60, 62–63; Tairov, Botalov, 1988: 100; Ageev, Sungatov, Vildanov, 1998: 97, 99; Tairov, 2006: 84; Gutsalov, 2010: 58) resulting in cremation of the deceased (see Fig. 3, 2 , 5 ; 4, 7 ) (Stokolos, 1962: 24; Moshkova, 1961: 119–122; 1972: 64–66; Pshenichnyuk, 1983: 57–60). The number of burials containing burned remains of the deceased is about a quarter of the total number of complexes in the investigated sample (see Fig. 2, B). Accompanying burials of dependent people have been found in some burial mounds (Kadyrbaev, Kurmankulov, 1976: 149; Kadyrbaev, 1984: 90; Gutsalov, 2010: 58, fig. 5, 2 ). In one such burial (Kyryk-Oba II, barrow 18, burial 1), the posture of the buried person in a flexed position on his side (Gutsalov, 2010: 58, 61) was untypical for the nomads. Judging by the few published anthropological definitions, males, females, and children were buried at the level of the ground surface (Smirnov, 1975: 43; Gutsalov, 2010: 61; Morgunova, Kraeva, 2012: 163).

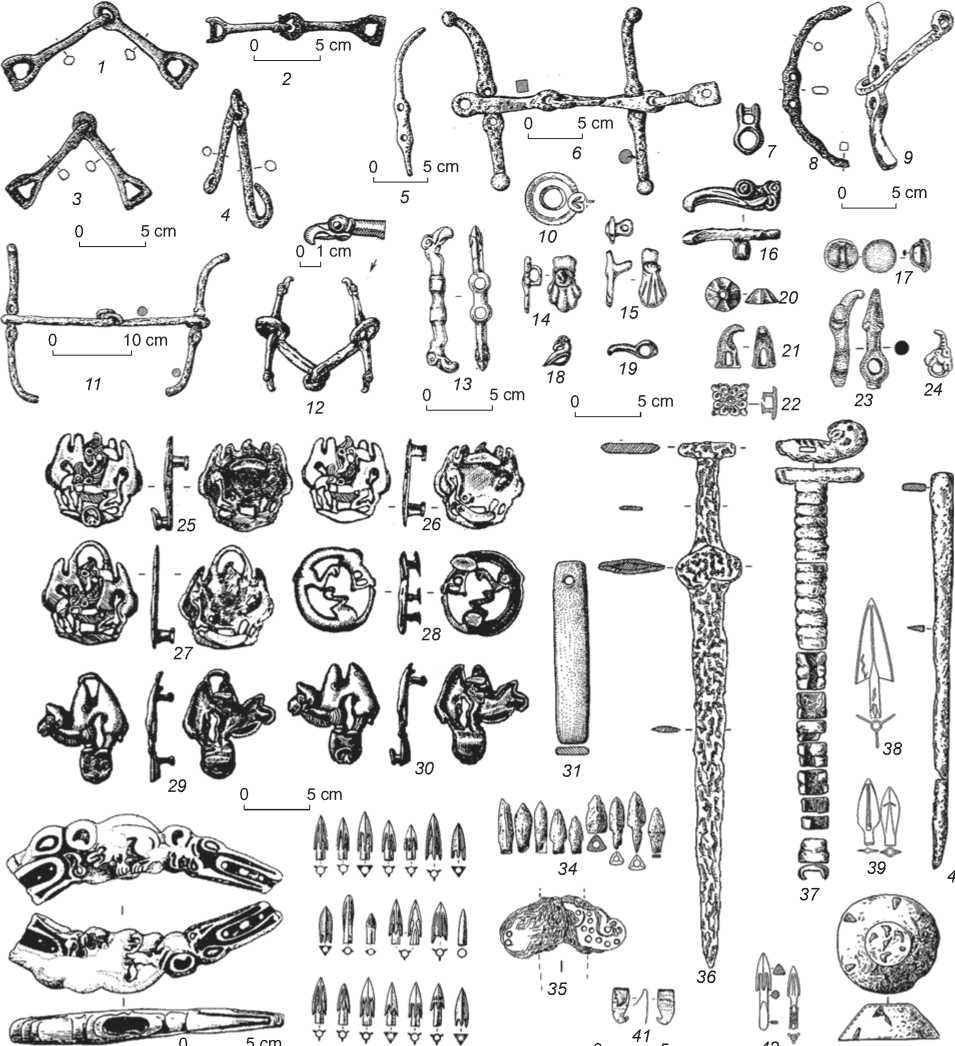

When describing the composition of the accompanying goods, it should be noted that the barrows in question most often contain clay vessels, which served as containers for food and drink (see Fig. 2, B), and mostly consisted of handmade flat-bottomed pots (Fig. 5, 1–5 , 9–11 ). Most burials contained objects of everyday life and household production, such as knives, needles, awls, whetstones, or spindle whorls (see Fig. 2, B). Quiver sets of arrows with bronze (rarely iron) socketed and sometimes tanged arrowheads prevailed among the objects of military use (see Fig. 2, B) (Fig. 6, 33 , 34 , 38 , 39 , 42 ). Swords were the next most frequent type of weaponry (Fig. 6, 35 , 36 ). Almost a third of all the burials contained implements for sword belts. Spears occurred rarely. The materials of over a half of the burial mounds contained objects of horse harnesses (Fig. 6, 1–30 ). The accompanying goods also included various kinds of feminine items (see Fig. 2, B). Personal adornments such as beads, earrings, bracelets, or sewn plaques have been most often found in burials (see Fig. 5, 27–33 , 36 ). Mirrors were also a common type of find (see Fig. 5, 12–20 ). Small portable stone altars have been found in a quarter of all burials (see Fig. 5, 21–25 ). Many burials are distinguished by a large number of accompanying goods, including objects of social prestige made of gold or overlaid with gold foil (Kadyrbaev, 1984: 88–89; Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: 144; Gutsalov, 2010: 61). Parts of carcasses of horses, sheep, or cattle were placed in the burials as food for the deceased (see Fig. 2, B). In general, a large percentage of burials contained rich and varied funeral goods.

The diameter of the barrows varied from 10 to 60 m; their height varied from 0.35 to 4.85 m. Notably, many burial mounds of the investigated sample were of large size (height ≥ 1.7 m, diameter ≥ 28 m). The mounds were mostly earthen. Stratigraphic observations have made it possible to determine that two burial mounds (Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 2; the barrow near the village of Varna) were initially made as stepped pyramids round in plan view (Tairov, Botalov, 1988: 110–114; Tairov, 2006: 79). The practice of encasing earthen mounds with stone or making stone mounds was not very common (Fig. 2, A).

The tradition of burials on the level of the ground surface was most widespread among nomadic cattle breeders, whose pastures were located in the upper reaches of the Ural, Sakmara, Ilek and Khobda rivers. Barrows with such burials in the basins of these rivers are found in a strip (see Fig. 1) stretching from north to south, which could have been caused by meridional seasonal migrations of groups of nomads who were close in ethnic and cultural terms. In the Southern Ural steppes, which extend west of the above area, such complexes have been found in smaller numbers (see Fig. 1).

Burials on the level of the ground surface in the barrows of the nomadic cattle breeders of the Southern Urals go back to the second half of the 6th–4th centuries BC. However, burial complexes with relatively “narrow” dates are distributed unevenly within this chronological range. Two complexes (the barrow near the village of Varna, and barrow 2 at Marovyi Shlyakh) are dated to the second half of the 6th century BC (Tairov, Botalov, 1988: 107; Tairov, 2006: 90). Twelve burial mounds (Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 3; Solonchanka II, barrow 1; Sara, barrow 7; Tara-Butak, barrow 3; Kyryk-Oba, barrow 18, burial 5; Syntas I, barrow 2; Besoba, barrow 2; Sibay II, barrow 17; Bish-Uba, barrow 1, burial 5, and barrows 2 and 3; Almukhametovo, barrow 8) were made in the late 6th to first half of the 5th centuries BC (Tairov, 2006: 89; Smirnov, 1964: 153; 1975: 42–44; Gutsalov, 2010: 64; Kadyrbaev, Kurmankulov, 1977: 103, 114; Tairov, 2004: 3, 6–9, fig. 3, 8 , 15 ; 8, 91; Ageev, Sungatov, Vildanov, 1998: 100; Berlizov, 2011: 183–186; Treister, 2012: 268, 270–271). Four burial mounds (Alandskoye I, barrow 1; Alandskoye III, barrow 6; Sara, barrow 6; Akoba II, barrow 1, burial 1) were dated to the 5th century BC or, more precisely, to the second half of the 5th century BC (Moshkova, 1961: 122; 1972: 68– 69; Vasiliev, Fedorov, 1994: 127; Morgunova, Kraeva, 2012: 196, pl. 1). Barrows 7 and 8 at the Perevolochan I cemetery can be dated to the second half of the 5th to the turn of the 5th–4th centuries BC (Sirotin, 2016: 253–256). Barrow 6 of the same cemetery is a part of funerary complexes dated to the late

15 cm

10 cm

10 cm

10 cm

10 cm

10 cm

0 10 cm

15 cm

10 cm

10 cm

10 cm

у 16

10 cm

10 cm

■ 0

19 -

10 cm

10 cm 20

10 cm

.a

^ОЙ

10 cm

0 2 cm

0 2 cm

^ SI S3 SB #^@@ ®(iD®aD

СИЗО mnte sme 30

5 cm

oe ®0

5 cm

2 cm

5 cm

0 2 cm

Fig. 5 . Main types of accompanying goods from the barrows with burials at the level of the ground surface.

1–11 – vessels; 12–20 – mirrors; 21–25 – altars; 26 – bag and stick; 27 – sewn plaques; 28–31 – beads; 32 – bracelets; 33 – earring; 34 – wheel amulet; 35 – pin; 36 – medallion, a part of a composite adornment.

1–11 – clay; 12–20 , 32 , 34 – bronze; 21–25 – stone; 26 – leather and wood; 27 , 33 – gold; 28–31 – glass; 35 – silver; 36 – gold, enamel.

1 , 2 , 14 , 23 , 27 , 30 , 31 – Besoba, barrow 4 (after: (Kadyrbaev, 1984: Fig. 1, 10–13 , 16–22 , 51 ; 2, 1–3 )); 3 – Ivanovka III, barrow 1 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XXVIII, 11 )); 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 – Alandskoye III, barrow 6 (after: (Moshkova, 1972: Fig. 8, 4–7 )); 6 – barrow near the village of Varna (after: (Tairov, Botalov, 1988: Fig. 3)); 7–9 , 12 , 21 , 29 , 34 – Almukhametovo, barrow 8 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XXIII, 1–5 , 19 , 21– 22 )); 13 – Solonchanka II, barrow 1 (after: (Tairov, 2006: Fig. 8, 4 )); 15 , 16 , 19 , 26 , 33 , 35 – barrow 7 near the village of Sara (after: (Smirnov, 1964: Fig. 35B, 7–9 , 12 , 14 , 15 )); 17 , 28 – Akoba II, barrow 1, burial 1 (after: (Morgunova, Kraeva, 2012: Fig. 8, 3–6 ; 9, 1 )); 18 , 25 – Zhalgyzoba (after: (Gutsalov, 2004: Pl. 7, 17 , 37 )); 20 – Alandskoye I, barrow 1 (after: (Moshkova, 1961: Fig. 46, 11 )); 22 – Sibay II, barrow 13 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XLIII, 36 )); 24 – Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 3 (after: (Tairov, 2006: Fig. 5, 5 )); 32 – Tselinnoye, barrow 1 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl.

XXV, 12 , 13 )); 36 – Filippovka I, barrow 15, burial 1 (after: (Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: Fig. 3)).

5 cm

Fig. 6 . Main types of accompanying goods from the barrows with burials at the level of the ground surface.

1–4 – bridle bit; 5 , 8 , 13 , 23 – cheek-pieces; 6 , 9 , 11 , 12 – bridle bits and cheek-pieces; 7 , 10 , 25–30 – buckles and plaques of horse harness; 14–19 , 21 , 22 , 24 – pendants and plaques of horse bridle; 20 – tassel bead; 31 – whetstone; 32 – object decorated with a representation in animal style; 33 , 34 , 38 , 39 , 42 – arrowheads; 35 – crossbar of a sword; 36 – sword; 37 – sheath of a knife; 40 – knife; 41 – braces (decorations of wooden vessels?); 43 – umbo or decoration of a quiver.

1–6 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 43 – iron; 7 , 10 , 13–19 , 21–30 , 33 , 38 , 39 , 42 – bronze; 12 – iron and bronze; 20 – gold; 31 – stone; 32 – bone; 35 – iron and gold.

1–4 , 8 , 14, 15 , 32 – barrow near the village of Varna (after: (Tairov, Botalov, 1988: Fig. 2–5)); 5 – Sibay II, barrow 19 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XLIII, 32)); 6 , 11 , 31 , 34 , 37–40 , 42 , 43 – barrow 7 near the village of Sara (after: (Smirnov, 1964: Fig. 35, A, B)); 7 , 12 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 33 , 41 – Besoba, barrow 4 (after: (Kadyrbaev, 1984: Fig. 1, 1 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 15 , 23–43 )); 9 , 10 , 24 – Almukhametovo, barrow 8 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XXXIII, 15, 18, 20)); 13 – Marovyi Shlyakh, barrow 3 (after: (Tairov, 2006: Fig. 5, 2 )); 17 , 21 , 23 – Akoba II, barrow 1, burial 1 (after: (Morgunova, Krayeva, 2012: Fig. 9, 2–5 )); 18 , 25–27 – Besoba, barrow 5 (after: (Kuznetsova, Kurmankulov, 1993: Fig. 3, 8 , 11 , 13 )); 22 – Sibay II, barrow 17 (after: (Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XLIV, 24)); 28–30 – Besoba, barrow 9 (after: (Kadyrbaev, 1984: Fig. 5, 1 , 2 , 6 ; Kuznetsova, Kurmankulov, 1993: Fig. 3, 6 , 9 , 12 )); 35 , 36 – Kyryk-Oba II, barrow 18 (after: (Gutsalov, 2010: Fig. 5, 3 , 10 )).

5th–4th century BC (Ochir-Goryaeva, 2012: 260, 271, ill. 285). Four more burials (Lebedevka VI, barrow 26, burial 1; Filippovka I, barrow 15; Sagitovo III, barrow 1; Tselinnoye, barrow 1) were possibly made in the 5th century BC, most likely in its second half, or in the 4th century BC (Zhelezchikov, Klepikov, Sergatskov, 2006: 37; Pshenichnyuk, 1983: Pl. XXVIII, 4–5, 11; XXXIII, XXXVII, XLIII, 1–11, 34–35: 37–38; Tairov, 2004; Balakhvantsev, Yablonsky, 2007: 147–149).

Conclusion

The burials of nomads of the Southern Urals, overviewed in this article, are distinguished by a stable set of features characterizing the funerary rite. These features include the tradition of burials on the level of the ground surface or on wooden floors or platforms, the collective nature of burials, and the orientation of the heads of the buried to the south. The deceased were buried in above-ground burial structures (mostly built of logs), which had square or rectangular plans and a flat or tent-like covering. This set of features also includes the tradition of burning the burial structures. A significant number of burial mounds were of large size (height ≥ 1.7 m, diameter ≥ 28 m). During the burial process, sophisticated burial structures were erected. In case of several mounds, the accompanying burials of dependent people were made. The majority of burials contained rich funeral goods and food. Therefore, there is reason to believe that this set of ritual traditions is to a large extent associated with the subculture of the nomadic elite of the Southern Urals.

Burials at the level of the old ground surface are concentrated in the eastern regions of the southern Ural steppes. It is possible that their location in a strip stretching from the south to the north in the basins of the upper reaches of the Ural, Sakmara, Ilek, and Khobda rivers was caused by meridional seasonal migrations of nomadic communities inhabiting these territories.

Ritual standards manifested in the burials under consideration, shows the specific local nature of the culture of cattle breeding tribes that roamed in the eastern regions of the southern Ural steppes. These traditions were most widespread in the second half of the 6th to the first half of the 5th century BC. From the turn of the 5th–4th centuries BC, their importance began to diminish. In the 4th century BC, this set of traditions of funerary rite ceased to exist.

Acknowledgement

This study was performed under the Public Contract of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (Project No. 33.1907.2017/ПЧ)