Shatra and jurt: the “return address” in the Altaian ritual

Автор: Arzyutov D.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145267

IDR: 145145267 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2016.44.3.111-120

Текст статьи Shatra and jurt: the “return address” in the Altaian ritual

In May 2010, I had the opportunity to observe the process of making small figurines out of cheese ( shatra ) and to participate in the ritual. All this happened through the religious movement of Аk-Jаng , which has been becoming increasingly popular over the last decade in the Karakol and Ursul valleys of the Altai Republic, in the same place where the Burkhanist rituals were commonly practiced in the early 20th century (see (Tadina, Arzyutov, Kisel, 2012)).

It was already about 10 pm. I was at the house of my friends, an Altaian jarlykchy (spiritual leaders in the

*Supported by the Russian Science Foundation project (No. 14-18-02785) and by the Arctic Domus project (ERC, AdG295458).

Ak-Jang movement) and his wife; we were waiting for a guest who was supposed to carve figurines of cheese ( shatra ) for placing them on each of ten stone altars ( tagyls ) in the early morning on the next day during the mÿrgÿÿl collective prayers*. The byshtak -cheese was brought earlier that day by another participant of the ritual who had made it early in the morning**. Jalama -

Fig. 1 . Shatra . 2010. Photograph by the author.

bands (they are also called kyira ) in four colors (white, blue, yellow, and green) were also prepared. Finally, our guest, who was about 30 years old, arrived. As my friend said, the carver had to be a young married man. The trays which were especially prepared for the ritual, were already on the table; the cheese was lying on a wooden board, and a knife was placed next to the cheese. All these were covered by a white cloth. The fellow came in quietly, sat down at the table and, exchanging a few words with the hostess, removed the white cloth and began to carve…

The house was quite, and the only motion came from the hostess carrying the trays with the ready small figurines made of cheese and arranging them on the bed in the same room. All the people gazed at the maker looking closely at his every move. Stealthily, I was able to ask questions of the hostess who was one of the main experts on everything that was happening. She explained in a whisper that the fellow was carving small figurines of domestic animals, aiyl (a model of Altai dwelling), and of a man and a woman, and this entire composition as a whole symbolized a jurt (the household, comprising the family, the livestock, and the buildings). The fellow finished his carvings by about midnight, at which point, frankly speaking, everybody could barely keep their eyes open. Ten trays with the shatra * were on the table (Fig. 1). Each tray had chaky (“a hitching post”), ottyn bazhy chaky (“a hitching post at the head of the hearth”), ui (“a cow”), at (“a horse”), koi (“sheep”), tuular (“mountains”), the symbols of the six corners of an aiyl , ochok (“a hearth”), er-kizhi (“a male”), ÿi-kizhi (“a female”), jangyrtyk (“a platform for things”), ayak / salkysh (“dishware”),

*I brought exactly the same figurines which the carver had made to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of RAS (Collection No. 7589).

bozogy (“a threshold”), and törding kaiyrchagy (“a chest where ritual objects are stored”). The remaining cheese was placed into a wooden bowl which, just as the trays, would be taken to the tagyl the next morning. Everyone began to slowly leave the house to meet the next day at dawn at the foot of a local hill ( bolchok ) and go to the mÿrgÿÿl .

The shatra figurines are interesting for several reasons. In the mountainous taiga, where the northern Altaians live, the hunters would place this kind of figurine near streams or on special platforms, expecting that they would materialize as real animal, the object of hunt. It is easy to correlate shatra with the history of shatrang / shatrandzh (chess) in the Mongolian steppes. In the coinciding names of shatra as a game and the ritual figurines, some scholars (Tyukhteneva, 2009: 89, note 1) see only homonymy (for the criticism of B. Malinovsky’s “doctrine of homonyms” in the Siberian anthropology, see (Broz, Willerslev, 2012)). The interplay of these traditions became reflected in the rituals of both Burkhanism (according to the data from the first third of the 20th century) and of the contemporary movement of Ak-Jang , where shatra is related to the idea of jurt .

This article analyzes the history and the place of the shatra in the contemporary rituals (we will use the spring ritual of jazhyl bÿÿr as a basis*). In order to analyze the figurines made of cheese** in the contemporary rituals of the Altaians, we should introduce the concept of “return address”. The participants of the ritual define the “direct addressee” or the one to whom the ritual actions are directed as eezi (“the master”, referring to the masterspirit of the place), or simply the Altai. S.P. Tyukhteneva wrote about it in more precise terms, “The addressees of the good wishes are, according to the texts, the Altai, the sun, the moon, the deity of Ÿch Kurbustan, Kayrakan (sky god), mountain tops sacred to the people of the area, and the trees” (2009: 88). In contrast, the “return address” is a manifestation of subjectivity in the ritual, a way to define oneself, which is precisely manifested by the figurines of cheese, their composition, and a specific order at the site of the ritual. Anthropologists designate such forms of definition using the concept of agency. Depending on the name (kochkorlor, shatra) and purpose of the figurines (for placing in the taiga, at a ritual site, for a game), such an “address” can be determined from three points of view:

-

1. Perspective from the taiga. In this case, the figurines constitute a symbolic representation of a wild animal which has to be killed. The taiga acts as the place of their creation and ritual use.

-

2. Perspective from a village. In this case, we may speak about a certain cattle breeding perspective, using small figurines of domestic animals, models of household material components, as well as images that represent the “domesticated” space (figurines representing the sacred mountains which are closest to the village and the river valley). Both settlements and ritual sites located in the ancestral territories act as the place of the figurines’ creation and ritual use.

-

3. Perspective from a gaming table. The figurines are used for playing the shatra game.

In defining these perspectives, I do not intend to place them in chronological order. This is more a means to endow the figurines with meaning in different locations, where one and the same person can be. Moreover, it should be mentioned that the economy of the Altai people manifests the hunting and the cattle breeding continuum or, according to A. Ventsel’s analysis of the Yakut materials, hunting and cattle breeding can be regarded as “complementary strategies” (2006).

Thus, the main purpose of this article is the analysis of all three variants of the shatra and kochkorlor in terms of connection between the figurines and the surrounding landscape, and in terms of expressing the subjectivity in the ritual.

Perspective from the taiga

The earliest information about small animal figurines made of clay or other materials is derived from the culture of the northern Altaians (jish kizhi)—the residents of the mountainous taiga who would make figurines before the hunt. A collection of such figurines is kept in the Russian Museum of Ethnography (Collection No. 597, items No. 12–16, published in (Ivanov, 1979: 77); Na grani mirov…, 2006: 265). S.V. Ivanov wrote about creating and using similar representations of animals on the basis of the words of the Altaian artist G.I. Choros-Gurkin (recorded in 1935), “The Altaians* called them kochkorlor (“mountain sheep”, argali, Ovis ammon – D.A.). In total, there should be 27 pieces. Such figurines were sculpted of oatmeal flour, the soft part of bread, clay, or farmer’s cheese. Then people would build a platform at a distance from their dwellings, cover it with a piece of birch bark, and set the sculpted animals on the birch bark. The sacrifice was offered to the white spirit Ayzan (the spirit with such a name is unknown – D.A.), the spirits of the earth, sometimes to a shaman-ancestor. The necks and the horns of the sheep were wrapped with yellow thread or cord” (1979: 77). A description of the same figurines was made by L.P. Potapov (1929: 131) and D.K. Zelenin (1929: 46). Potapov thus wrote, “(The Altaians) sculpt small figurines of goats and red deer out of barley flour and place them around the taiga in the belief that the Altai would turn them into living animals” (2001: 135). Here we may see the magical function of these animal sculptures, apparently quite comparable with the purpose of small statuary known from archaeological materials (see (Molodin, Oktyabrskaya, Chemyakina, 2000: 33)). As far as Southern Siberia is concerned, Ivanov pointed to the spread of similar figurines among Beltyrs, Shors, Kumandins, Teleuts, Altai Kizhi people, and Telengits (1979: 156–157). Parallels can also be found among the Ob Ugrians who would use the representations of birds (grouses), deer, elk, and horses made of oatmeal flour in the bear festival. Ivanov noted that “all this statuary is of relatively recent origin; it replaced birds, deer, or elk which in the past were killed at the festival and whose meat was then eaten. This is indicated by the breaking of the dough figurines” (1970: 50). Kozulki / kozuli among the Pomors, small figurines made for Christmas and representing deer, horses, cows, and others, can be regarded as another parallel to the kochkorlor. Such figurines were made of flour and were then given to children after they sang Christmas carols. The figurines remaining at home were kept and used as Easter food; they were also given to the cattle to eat in the case of illness (see (Zelenin 1991: 401; Propp, 1995: 38–39)).

Unfortunately, I do not know what exactly the Northern Altai hunters would do with the figurines (eat them, break them, etc.). Figurines for hunting and cattle breeding purposes differ in terms of their material: the former are made of grains (bread, oatmeal flour), while the latter are made of dairy products (cheese).

Grains and vegetable foods are very diverse among the Altaians, particularly in the north of the region (see (Potapov, 1953; Muytuyeva, 2007: 100–146)), but their status was also high in the Central/Eastern, predominantly cattle breeding Altai (Ongudaysky and Ust-Kansky districts), as evidenced by a very beautiful Altaian greeting, “What are the news mixed with the scent of onions?” (“ Solung-sobur, sogono, jyttu ne bar? ”). The connection between hunting and vegetable food can be seen in the traditional implements, “Skins of animals, especially wild animals, had great value in storing flour products. Such skins were waterproof ( chyk tartpas ).

The Altai Kizhi people made suede out of animal skins and produced bags of various sizes ( bashtyk ) for keeping kocho , or ready talkan . They would sew leather bags “ tektiy ” out of argali skins. In addition, the bags “ tulup ” made of bovine cattle and horse skins were used for household needs for storing barley and other foods” (Muytuyeva, 2007: 127).

Hunting figurines focus on wild animals ( ang ). Their placement primarily defines the taiga*, and the set of figurines from the known descriptions and field materials of the author contains no other representations besides those of wild animals.

Perspective from a village

Comparing the figurines made of grains (hunting figurines) and of cheese, Ivanov pointed out that apparently they should be distinguished, and the latter could act as “decoration” and “scenes from the Altaian life” (1979: 76). The opposition of vegetable and dairy products can be found in the Altai language and rituals. Thus, dairy products ( ak ash , “white (sacred) food”) is closely related to the Burkhanist rituals, and the religious movement itself in one of its versions was called sÿt jang , the “milk faith”. In the Altaian tradition, the cow belongs to the sook tumchyktu mal class of animals (“animals with cold breath”) and is associated with the Lower World. Precisely cow’s milk is needed for producing the cheese used for making the shatra . In keeping with the structuralist model of interpretation, V.A. Muytuyeva pointed out that the cheese-manufacturing procedure by itself would change the status of the product by “purifying it” (2007: 65). The animals that are represented in the shatra composition are divided into two groups: those with cold breath and those with hot breath. Thus, cow figurines are placed on one side of the representation of the hitching post, while sheep and horse figurines are placed on the other side (Fig. 1, left side of the tray; for more details see (Broz, 2007)).

At present, the composition of the cattle breeding figurines entails the representation not only of domestic animals, but also of dwellings and people. Usually, the researchers of Burkhanism pointed out that this composition testified to the transition to a bloodless sacrifice. Tyukhteneva mentioned the shatra and its parallel balyng / balgyn* * associated with celebrating

*The word “ taiga ” also has a meaning of “a mountain covered with forest” which is associated with the hunting places (Oirotsko-russkiy slovar, 1947: 139).

**Apparently, this word is known only in the south of the Altai. The word balin can be found in the Mongolian language in the sense of “small sacrificial flour figurines, sacrificial bakery, offering, sacrifice” (Bolshoi akademicheskiy mongolsko-russkiy slovar, 2001: 221).

the New Year, Chaga Bairam , primarily in the south of the Altai (2009: 89). According to her information, the ritual figurines were burned on the tagyl . The Altai people living in the valleys of the Karakol and Ursul rivers do not burn the figurines, but simply leave them on the tagyl (see below for more details).

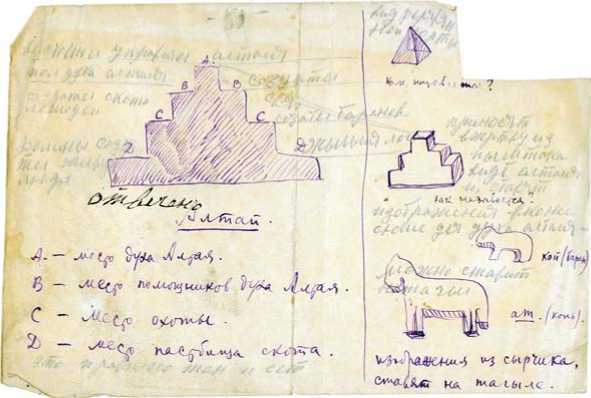

The materials collected by A.G. Danilin show the structure of the shatra : figurines of horses, sheep, and “pyramids”*. Danilin distinguished between two types of “pyramids”: simple ( ^atra ) and stepped ( sak* *). He also pointed to the use of “bones from the legs of sheep” in the composition (1932: 73). The disappearance of the “pyramids” today might have been caused by what is probably the main idea of Ak-Jang , the struggle with Buddhism (Tadina, Arzyutov, Kisel, 2012: 409; Halemba, 2003). According to the field materials of Danilin, there was always an even number of figurines: 2, 4, 20, 24, 40, 42, or 100 objects (Archive of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of RAS (AMAE RAS), F. 15, Inv. 1, item 11, fol. 4v, 5v; see also the Archive of RAS, St. Petersburg Branch, F. 135, Inv. 2, item 102, fol. 40). Danilin observed insignificant variability in the figurines within the Ust-Kansky, Shebalinsky, and Ongudaysky districts (AMAE RAS, F. 15, Inv. 1, item 11, fol. 5v). The materials of Danilin contain a drawing, probably made according to the information provided by his informant K.I. Tanashev (about him, see (Tokarev, 1947: 144; Dyakonova, 1998; Kozintsev, 2010)), where the meaning of the top and each step of the “pyramid” is indicated (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that both places of hunting (C) and grazing (D) have been indicated in the drawing, which may be evidence of a certain blending of hunting kochkorlor and cattle breeding shatra .

A.G. Danilin and L.E. Karunovskaya, who collected materials on Burkhanism, brought shatra to the MAE from their expedition of 1927, although not the entire “set”, but only a “pyramid” made of syrchik (meaning the Altaian kurut cheese) and a small figurine of at, the horse. Unfortunately, both of these objects (MAE 3650-81 and MAE 3650-82) were lost by 1951 (according to the inventory of MAE 3650; see the only surviving illustration in (Ivanov, 1979: 76)). Danilin and Karunovskaya, who worked with Tanashev for a long time, recorded from him (?) a special “prayer” of the Altaians which they recited while referring to the shatra (AMAE RAS, F. 15, Inv. 1, item 50, fol. 36). The prayer uses the epithet “jort jelu kök shatra” (lit. “four-sided blue shatra”). The definition “kök” is noteworthy. I cited the original translation of Tanashev— “blue”, while the semantic field of kök includes blue, light-blue, gray, or green (especially when applied to young leaves), which gave N.A. Baskakov reason to speak about the “Turkic color-blindness” (see (Mayzina, 2006)). In the “prayer”, people appeal to the Altai who is asked to give children and cattle.

Despite the gradual forgetting of the meaning of the shatra elements, the ritual of arranging the figurines continued to exist. A person whom I personally knew (now he is 50 years old) said that when he was a child at the age of 10–12 years (that is, those events happened approximately in the early 1970s), he became sick and his father carved shatra (he does not remember what they looked like), and

Fig. 2 . Sketch of the shatra . AMAE RAS, F. 15, Inv. 1, item 61, fol. 76v.

brought them to arzhan-suu (“the spring”) not far from the village of Karakol in Ongudaysky District. Exactly the same purpose of shatra in the village of Kulady in the Karakol valley was described by E.A. Okladnikova, “These figurines <…> were regarded as a kind of offering to the spirits of the mountains and to the master of wild animals of the area” (1983: 173)*, and a little later, Okladnikova specified that the figurines acted as substitutes of real animals which were supposed to return to people. In our personal correspondence, Okladnikova mentioned the absence of human figurines in the composition of the shatra . Otherwise the composition which she saw was similar to the present-day composition, which was described in the beginning of this article. However, probably the most important piece of information was that at the end of the ritual the figurines were burned (the message was received by e-mail on October 14, 2012).

L.V. Chanchibayeva gave information on visitations to arzhan-suu in the Ongudaysky District. She said that the shatra were carved both of byshtak and kurut , and were placed on an altar made of stones. “These small figurines represented actual animals which were offered as a gift to the master-spirit of arzhan ” (Chanchibayeva, 1978: 95–96). It is important that in this case the taiga and the cattle breeding styles of the figurines still remained undivided.

A.I. Nayeva provided a description of a visit to arzhan-suu (curative springs) in the early 2000s. She mentioned that shatra in the form of people, household utensils, a yurt, and animals were an indispensable attribute of the ritual (Nayeva, 2002). We may observe here a further change in the idea of shatra and introduction of human figurines into their structure.

In 2012, before the beginning of Kurultai of sööka tölös in the place named Temuchin near the village of Yelo, people performed the ritual in which the shatra were placed on a flat stone near a birch tree with jalama / kyira tied to it. The shatra included the figurines of horses ( at ), mountain sheep ( kochkor ), a representation of a hitching post ( chaky ), and “pyramids”. In general, such a model is directly related to the Burkhanist model. We can say that various traditions of carving the figurines are followed in different situations.

In order to better understand the role which shatra played in Burkhanism in the early 20th century and plays in the contemporary ritual practices of the Altaians, we should turn to the use of shatra as a game.

Perspective from a gaming table

The Altaian epos Kozyn-Erkesh (Ulagashev, 1941: 219) mentions the game of shatra . This game was vaguely reminiscent of checkers (Slovar…, 1884: 445; Oirotsko-russkiy slovar, 1947: 185) and continued to be played even in the 1950s in the south of the present-day Altai Republic, in the Ulagansky and Kosh-Agachsky districts (Pakhayev, 1960). In the south, where the influence of the Mongolian culture was most pronounced, the parallels with shatra are associated with the vast history of chess (Murray, 1913; Orbeli, Trever, 1936; Kocheshkov, 1972; Eales, 1985). Chess originated in India; then the game penetrated through Tibet to Mongolia and further north to southern Siberia (Montell, 1939: 83; Vainshtein, 1974: 180). The lexical meaning confirms this in many ways. Thus, the Sanskrit caturanga (“four rows” / “four formations” (Montell, 1939: 82))

relates to the ancient Turkic shatrandzh / šatranǯ (Drevnetyurkskiy slovar, 1969: 521). Mongolian chess is called shatyr / chatyr / shatar (Savenkov, 1905; AMAE RAS, F. K-I, Inv. 1, item 62); the figurines could be made of stone, metal, or bone (Kocheshkov, 1972: 134). The name of the Tuvan chess sounds similar to the Mongolian— shydyraa (Murray, 1913: 311; Karalkin, 1971; Vainshtein, 1974: 178–180; Sat Bril, 1987), and its history, just like the Altaian shatra , is associated with the spread of Tibetan Buddhism in the region since the 16th–17th centuries. The main players in shydyraa were lamas (Savenkov, 1905; Karalkin, 1971: 137–138; Montell, 1939; Kabzinska-Stawarz, 1991: 28).

The history of shatra in the movement from south to north has left its mark on the external appearance of the figurines, which combine the discernable “Mongolian traits” with the local tradition of carving similar figurines. Such a synthesis sometimes opens up interesting possibilities for interpretation. Thus, I.U. Sambu drew attention to the fact that “Tuvan games ‘ buga shydyraa ’ and ‘ tugul shydyraa ’ resemble hunting” (1974: 21). Association with hunting can be important for two reasons: firstly, the game entails not simply a model of society, but a certain model of battle (this is suggested even by the Sanskrit etymology); secondly, it shows that the set of animal figurines changed from culture to culture, and was related to differences in the economic practices (see (Kocheshkov, 1972)). Already in the game, the military strategy has been replaced by the spatial metaphor. In this regard, I should cite the opinion of the medievalist S.I. Luchitskaya, who analyzed a treatise on the game of chess from the 13th century, “Chess is primarily a spatial metaphor of society (as, indeed, its bodily metaphor), and spatial symbolism which plays an important role in placing the pieces on the chess board, here coincides with social symbolism” (2007: 134).

External appearance of the figurines was not invariable and depended on local carving traditions. As opposed to the Tuvan figurines (Kisel, 2004), the Altaian figurines almost completely lost their original appearance. According to informant, K.N. Shumarov, today, three types of figurines are used: baatyr , biy , and shatra (in their status equal to pawns; in the Kosh-Agachsky District they are also called juuchyldar , “warriors”). All of them can be replaced with checkers with the identifying marks glued to them.

In the Altai, shatra as a game was revived only in 1970–1980. The employees of the Gorno-Altaysk Research Institute of History, Language and Literature took part in reconstructing the game. V.L. Taushkanov and B.T. Samykov played a great role in codification of the rules. However, the reforming of the rules has not received universal recognition, and today there are a number of shatra variants. Gradually, the game started to spread far beyond the southern regions of Altai, has received Altai Republic status, and since 1988 has been included into the list of competitions at the ethnic Altaian festival El Oiyn (lit. “folk game”). The local newspaper Altaydyng Cholmony often publishes the rules of the shatra game, the results of the tournaments, and reviews of gaming strategies (see, e.g., (Yadagayev, 2004)). In the village of Onguday, I have witnessed enormous enthusiasm of the local residents who actively participated in chess and shatra tournaments.

Just as figurines made of oat flour/dough/cheese, chess can be found in Northern Asia as the game of Dolgans, Yakuts, Evenki, Nenets, Nganasans, Yukaghirs, Kamchadals, and Chukchi. At the very beginning of the 17th century, chess was known to Russian Arctic sailors, from whom the game might have possibly found its way to the peoples of the North (see (Zamyatin, 1951)).

“Return address”

Anthropologists have noted the communicative nature of the ritual arranging the shatra on the tagyl . At the beginning of this article, I cited the information of Tyukhteneva on the variety of addressees for good wishes (2009: 88). It is important that each of them is connected with the entire environment and not with its individual components. For describing the surrounding landscape together with all living beings, the Altai language uses the notion of ar-bÿtken (cf. English “environment”). However, if we look on the other hand and try to see the people performing the ritual in this communication, we will see a slightly different picture. The suggested descriptions can be compared with the concept of the return address on a mail envelope, where the addressee locates himself in the culturally modified space of cities/ villages, streets, and buildings. However, when one needs to send a letter to a place where the usual order of space is distorted, referencing to the place becomes less obvious and the addressee begins to be associated with some other points on the map.

The Altaian family clans are directly connected with the Altai Mountains, and this link defines the relationship between humans and the landscape (Tyukhteneva, 1995). The cheese figurines are connected to the “master” of the area ( eezi ) through their arrangement on the ritual place ( tagyl ), represented by several layers of stones which symbolize the ancestral mountains. During the ritual, the participants choose their own stone altar on the basis of their own affiliation with the family clan. The composition of the figurines is not a sacrifice by itself, but an indication of the point on the map where the grace expressed in the wishes which were articulated or comprehended during the ritual, should descend. The composition of the figurines was defined by my

Fig. 3 . A tagyl with shatra . 2010. Photograph by the author.

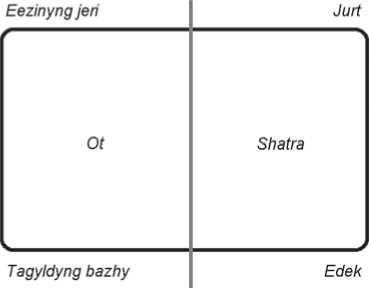

Fig. 4 . Meaning of places on the tagyl .

Eezinyng jeri – the land of the master-spirit, ot – fire, tagyldyng bazhy – the summit of the ritual space; jurt – household, shatra – small figurines made of cheese, edek – the foot (lit. “hemline”).

field partners as the jurt , that is, as a household, but at the same time they repeatedly emphasized that jurt has another meaning of “village”*, and for referring to the village the Altai language also uses the word teremne — a borrowing from the Russian (the modified Russian word “ derevnya ”, “village”), and in the case of the shatra , it is exactly the village where the tagyl is installed.

This ritual manifests the combination of the “ancestral” and “territorial” logic. The latter logic is so pliable that it even absorbed the Soviet policies aimed at creation and then consolidation of villages. Thus, stone tagyls symbolizing ancestral mountains and cheese figurines designating both the household and village, build up the perspective where both “mapping systems” work. The photograph (Fig. 3) and the diagram (Fig. 4) show how this intertwining is implemented. The multidimensional composition is recreated with the summit of the tagyl (in a symbolic sense) in its western part, where the fire is made, and with the foot of the tagyl in its eastern part with the figurines of cheese as a symbol of the jurt . The cubic shape of the tagyl is transformed into a pyramid with the top and the foot, and it is also linked with the cardinal directions and the space of the village. The interplay with the shatra game is of interest in that respect, where the board as well as the surface of the tagyl is divided into two parts. If in the game these parts belong to the opponents (the model of the battle), in the ritual they belong to the acting participants. The shatra arranged on the tagyl become the recipients of future grace and at the same time designate the participants in the ritual, while the place for the fire symbolizes the donor and the source of that grace.

The link between the mountains, the master-spirit, the settlement, the family clan, and the specific person who is giving the offering is visualized here. If we go back to the issue of family ties, the very expansion of the context of the shatra , its understanding as the household – the village – the territory, makes it possible to see that space is just a way of visualizing relationship; it creates a visible link between the surrounding space and kinship. This is why anthropologists also discern the logic of kinship in the chess game (Wagner, 2011).

The choice of where and why to put individual figurines, is not a mechanical one. The participants in the rituals (in both the cattle breeding and the hunting types) choose a certain composition based on their relationship with the landscape and the animals, as well as their own social experience. Each time, preparing for hunting, or calving/lambing of the livestock, the person creates a model of space where these social, economic, and environmental relationships would be most relevant (the taiga or settlement). The game which came from the “south” has become an important factor in organizing the composition of the figurines, in giving it structural nature and explicit social references. The figurines in the ritual both in the taiga and during mÿrgÿÿl are a reflection of relationships between the local community and the landscape, defining the purpose of the prayer and showing the “return address” of the message, turning the ritual into a message to oneself, as it was noted by E. Leach (1976).

If we return to the Burkhanist figurines, they still manifest undivided hunting and cattle breeding trends in the structuring of the symbolism. Gradually, the hunters’ kochkorlor have started to represent exclusively wild animals as opposed to the cattle breeding shatra representing domestic animals. This opposition took shape in the dialogue between the “village” and the

“taiga”. It may be observed that “village–taiga” as a pendulum of economic activity of the Altaians in the western (central) part of the Republic, affects the rituals with the shatra and makes it possible to speak about the changing relationship between man and the landscape, a change in the methods of localization in the landscape. The figurines symbolizing cattle/wild animals are the stable part of the shatra both in the village and in the taiga.

The studies on hunting groups in Siberia indicate that it is as if the hunter disappears into the taiga and starts to imitate the animal world (Willerslev, 2004). In this space, his denotation might destroy fine binding threads between man and animal. Therefore, the magical action of arranging the figurines made of oatmeal flour or clay defines not a person as a hunter, but wild animals that the hunter would like to kill. This logic has more to do not with a specific place or group (for example, the northern Altaians), but with the relationship with the landscape. In this situation, it is as if the hunter clarifies the uncertainty, trying to predict the hunting luck (cf. (Broz, Willerslev, 2012)).

If we compare the hunting and the cattle breeding shatra , we can see an additional dimension. If in the forest the hunter deliberately “erases” time, going beyond sociality, the representations and arrangement of the figurines for mÿrgÿÿl refer to timelessness: all human and animal figurines are located within/ near the ayil which in the daily life for quite a long time has not been used as a dwelling but as a summer kitchen (cf. (Arzyutov, 2013: 123–124)). Through the interpretation of the ayil one may see the practices related to “museumification” of nature and to the ritual management not only of space, but also of time. Such a turn to timelessness speaks for the emphasis on the figurines and their relationships with space.

The game of shatra which came from Tibet, has undergone a change from the logic of battle to the spatial metaphor of ritual figurines in the Altai. In the chess game itself, in spite of the desire for spatial ordering of social roles through the figurines, the context is being lost, becoming limited by the chess board. On the contrary, in the case of ritual figurines, the models aspire to such diverse and multidimensional contexts that they seem to appropriate the surrounding area both in the social, mythological, and geographical sense.

Conclusions

The analysis of the shatra gives reason to consider them as a certain node in a network of diverse relationships between humans, animals, landscapes, things, and spirits. The certain freedom with which an Altaian person creates a composition symbolizing the jurt, and after a while, when going on a hunt, he creates the kochkorlor, a different composition using the figurines of wild animals, suggests that the choice of strategies is associated with the need to define oneself in the landscape as a sculptural composition which can be seen from above. This upper point may be located on the western side of the tagyl, the opening space for the syntagmatic chain, including both kinship (ancestral mountains) and spatial localization (the tagyl of a certain village), but it may also be located on the top of a mountain in the taiga, where the arranged figurines rather resemble the model of the herd. The very existence of votive figurines, arranged in a certain order, automatically suggests the thought about the presence of a deity-like observer. Since the addressee of good wishes is not very specific as Tyukhteneva aptly observed (2009: 88), there is mobility in respect to the shatra, the addressee, and the “return address”. It is exactly here that we may see agency where freedom of choice and action make it possible to build up multiple models of relationships, sometimes stable and sometimes fragile, just as the figurines of cheese. In the diagram which shows the meaning of different parts of the tagyl (Fig. 4), the pair of “east–west” in the stonework determines the axis of the two “addresses”.

Along with the shatra , Altaians have other kinds of small gaming and votive figurines which are related to human activities and the landscape where these activities are carried out. This multiplicity in the use of figurines gives an idea of the dynamics of the social life among Altaians for over the past hundred years.