Shift of the Yenisei and Abakan Beds as Reasons for Constructing the Second Abakan Fort in 1707

Автор: Skobelev S.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The study explores the reasons behind the relocation of the construction site for Fort Abakan from the mouth of the Abakan River, as initially planned, to the right bank of the Yenisei River, between two mountains, Unyuk and Turan. The shift of sand ridges, damming these rivers and changing their beds, is examined, and the locations of the projected forts are described. Written sources suggest that the Abakan and Yenisei beds as related systems changed their positions simultaneously, likely between 1691 and 1697 and definitely no earlier than 700–400 BC. Modern hydrological data suggest that processes that occurred in the region in the Early Modern Age were essentially like those that occurred in the Early Iron Age. The earlier date of the Abakan bed’s change is evidenced by the destruction of the 1st millennium BC Tagar sites near Sartykov village on the Abakan. At present, the Yenisei makes an abrupt eastward turn in that place, following the general direction of rivers in the region. D.A. Klements’s idea that after leaving the Western Sayan canyon, the Yenisei had flowed westwards is rejected. The change of location for the prospective fort was caused by the evolution of riverine systems of Western Siberia, specifically by the shift in the Abakan bed.

Yenisei Region, 18th century, second Abakan and Sayan forts, construction locations, unsuitability of projected locations, relocation of construction sites, hydrological factors

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146961

IDR: 145146961 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.4.114-118

Текст научной статьи Shift of the Yenisei and Abakan Beds as Reasons for Constructing the Second Abakan Fort in 1707

The Russian expansion to Siberia, particularly in the 18th century, implied the construction of a wide network of defensive facilities owing to the presence of external and internal military threats. On the territory of the Yenisei region during Peter the Great’s reign, the second Abakan fort (1707, the first was built in 1675, but quickly ceased to exist, probably destroyed by the Yenisei Kyrgyz) and Sayan fort (1718) were built (Fisher, 1774; Kozmin, 1916, 1925; Kopkoev, 1959; Arzymatov, 1966; Istoriya Khakasii…, 1993: 192, 193, 195; Abdykalykov, Butanaev, 1995; Kyzlasov, 1996; Chertykov, 2007: 220, 221; Butanaev, 2007). The practice of Russian defense architecture, before the start of construction of a specific object, involved a search for the most suitable location. The search consisted of collecting information from all possible sources, including the results of field exploration routes and interviews with knowledgeable people. For example, even before the decision was made to create the second Abakan fort, the Krasnoyarsk Governor (voivode) pantler Lev Mironovich Poskochin by 1691 had collected the information about suitable places for the future fort on the Abakan River. In his conclusion, the voivode noted the availability of places for building a fort, where it was possible to settle 400 or more service people and many peasants; with large pine forests, arable lands, meadows, and good hunting and fishing grounds. Poskochin’s message notes that the geographical reference was the “Rock”—the ridge of the Western Sayan, located near the Abakan River of that time (Chertykov, 2007: 221).

However, according to the testimony given by Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Kuznetsk servicemen in the Sibirsky Prikaz in 1697, there were no good conditions for putting a fort on the Abakan River: there were no pine forests, nor hunting grounds, nor arable lands, and the soil was sandy (Ibid.) and pebble. There was no mention of the location of the Western Sayan ridge near the site of the proposed construction of the second Abakan fort. In the same year, this information was confirmed by other Krasnoyarsk servicemen in the Sibirsky Prikaz, as well as by two local “Tatars” who believed that the fort should be built, not on the Abakan River, but at the mouth of the Tuba River—half a day’s journey downstream from the mouth of Abakan at that time (Ibid.: 222).

Despite everything, a final government decision was made to create the second Abakan fort on the eponymous river; and a team of builders, staffed by servicemen from Krasnoyarsk, Yeniseisk, Tomsk, and Kuznetsk, headed to the mouth of the Abakan in July 1707. The construction managers who arrived at the intended site sent a reconnaissance group up the Abakan and, on the basis of the data received from it, concluded that the area at the mouth and further upstream really did not meet the accepted requirements for placing a fort. There were many swampy areas, and an insufficient amount of construction timber or other forest lands (a small pine forest existed only on Tagarsky Island, on the right bank of the Yenisei), opposite Mount Samokhval. There were no conditions for arable farming and, consequently, for resettlement of peasants, because the turf layer over the pebble and sandy bottom was weak, which did not allow plowing (the land around the mouth of the Abakan is not plowed today, either). As a result, the fort was built on the right bank of the Yenisei, 70 km downstream the mouth of Abakan, between the Unyuk and Turan mountains. The fort was named, as planned, Abakan (Ibid.: 222).

Fort Sayan was also not built at the place indicated in the assignment, but 7–8 versts downstream the Yenisei, where the river flowed out of the Western Sayan canyon. The new site differed from the one “marked” for construction (now it is the southern part of the town of Sayanogorsk), which was narrow, squeezed by the river and the edge of the Yenisei canyon, and also poorly protected from floods, since it was located on a rather low bank. At the new site, the normal height of the bank above the water’s edge was ca 9 m. On both banks of the Yenisei River between the modern villages of Novoyeniseika (Beysky District of the Republic of Khakassia) and Ochury (Altaisky District), there are large tracts of pine forest. On the right bank of the Yenisei, near the Shunery village (Shushensky District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory), there are vast fields with rich chernozems, fully suitable for arable farming, as well as a large pine forest. Notably, from the territory of Fort Sayan, although only over a limited area, it was possible to monitor the entire channel of the Yenisei; this is a very important point in terms of fortification.

In connection with the above, the question arises why the area around Abakan in the message of the voivode Poskochin was assessed as suitable for building a fort, although according to the testimony of service people, was unsuitable for this task. The purpose of this article is to identify the reasons for the relocation of the construction of the second Abakan fort.

Study results and discussion

Both forts—the second Abakan and Sayan—were located on the right bank of the Yenisei, as was stipulated in the construction assignments. Both also have in common the fact that the fortifications were erected in places other than those initially planned, a circumstance quite rare in the history of Russian fortification of Siberia in the 18th century (Pamyatniki…, 1882: Doc. No. 78, p. 313).

As for the second Abakan fort, the discrepancy in assessments of supposedly the same area in which the fort was planned to be built can be explained if we assume that between 1691 and 1697, the beds of the Abakan and Yenisei rivers changed. Voivode Poskochin’s informants inspected the area near the old stream, at the foot of the Western Sayan. His descriptions correspond to the modern natural situation, for example, the presence of a dry pebble bed and traces of river backwaters near the Ochury village. However, the builders of the second Abakan fort observed the mouth of the Abakan already in a new place (where the city of the same name now stands), which was recognized in 1707 as unsuitable for the construction of a fortified settlement.

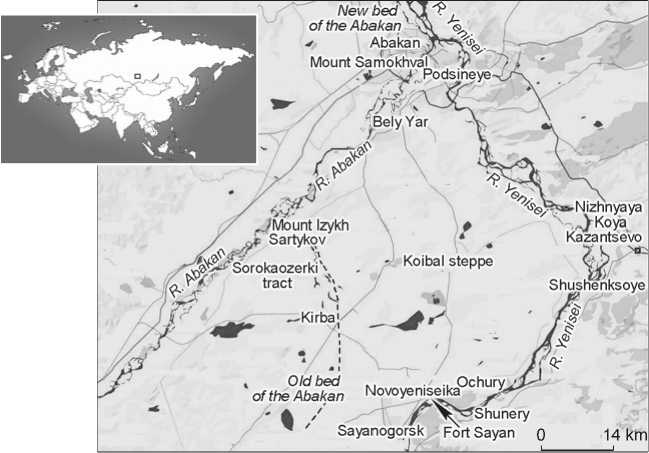

D.A. Klements was the first to consider this problem (Kozmin, 1916: 35–64). He suggested that the Yenisei changed its bed below the Oznachennaya village, which existed at that time, at the exit from the Western Sayan canyon, having made a turn to the west in the steppe. The floor for the Yenisei River was the supposedly modern bed of Abakan in the area from the village of Sartykov (Altaisky District of the Republic of Khakassia), slightly above Mount Izykh. Unfortunately, this scholar did not indicate the time of this event.

There is the following objection to this version: at present, there is no natural gravity flow of the Yenisei to the north and west directly when it leaves the Western Sayan, since both banks are high and steep here, oriented to the east. Therefore, for example, irrigation systems in the Koibal steppe, which operated during Soviet times, were filled with water from the Yenisei only with the help of powerful pumps. The fact that today the Yenisei, from its exit from the Sayan ridge, flows in the eastern and even southeastern directions, but not in the western, also needs to be explained.

Modern map of the research region.

According to V.K. Chertykov, the Abakan River near Mount Izykh was making a turn and was flowing into the Yenisei near the village of Oznachennaya in the period of 1691–1697 (2007: 231). However, this assumption does not take into account the mainly northward direction of water flows in the region, or the fact that Oznachennaya is located far south of Mount Izykh.

The lower date of the shift of the Abakan bed can be established by such an indirect sign as the erosion by the river of Mount Izykh, where several archaeological sites of the Early Iron Age were partially destroyed by water (their remains were studied in 2022 by the archaeological team of the Katanov Khakass State University, with the participation of the author). Considering this, it can be assumed that the destruction of the foot of Mount Izykh occurred no earlier than the 5th–7th centuries BC and no later than the end of the 17th century AD.

Importantly, the author had chances to visit this place in 1985 and 2022. During the first visit, it was recorded that the fast rushing water of Abakan was in direct contact with the foot of the mountain, beating forcefully against the rocks; during the second visit, the river bed significantly (up to 100 m) retreated into in the northern direction, and on the drained part of the floodplain, where high water used to flow in the past, 30-year-old trees now grew. Hence, today, there is no immediate threat of erosion of the riverbank near the Sartykov village, with the archaeological sites located here, but the possibility of their destruction by rain and spring freshet remains.

The most noticeable traces of the former bed of the Abakan—a flat swampy area—remained in the large Sorokaozerki tract in the interfluve of the Yenisei and Abakan, in the center of the Koibal steppe, near the village of Kirba (Beysky District of the Republic of Khakassia) (Urochishche Sorokaozerki… (s.a.)). These are “chains” and individual small lakes (Adaikol, Berezovskoye, Bugaevo, Zhuravlinoye, Zalivnoye, Kochkovskoye, Krasnoye, Moyrykhkol, Okelkol, Podgornoye, Ptichye, Sabinskoye, Sobachye, Sosnovoye, Stolbovoye, Chalpan, Chernoye, etc.), usually of elongated in shape, oriented almost along the N–S line, with deviations to the NW and NE. Most of them are located north of the village of Kirba.

Changes in the Abakan bed can be reconstructed as follows. After reaching the plain, the river flowed east along the Western Sayan ridge (“Rock”) to the point where the Yenisei exits the Western Sayan canyon. It was this area that was mentioned in the documents as “Rock” (the Western Sayan ridge), as well as favorable conditions for the settlement of peasants, possibility of farming, etc. However, later, as a result of hydrological processes, the Abakan runoff rushed in a northern direction, through the future Sorokaozerki tract, to a place further up the foot of Mount Izykh. The Yenisei River, after leaving the Western Sayan canyon, passing, as noted, to the NE, then to the E, and near the Shunery village again to the NE, created a long bow facing far to the E from the place where the river exits the canyon, with a maximum distance at the villages of Kazantsevo and Shushenskoye (Shushensky District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory); then, the river flowed in a northwestern direction, receiving the largest left tributary, the Abakan River, higher up Mount Samokhval. In connection with the version proposed by Klements, it is important to note that the flow of the Yenisei in a western direction is unlikely owing to the presence of high banks here; in addition, the Yenisei and Abakan rivers generally move in the eastern and northeastern directions.

The author’s assumption is consistent with the evolution of river systems in Western Siberia. This is a former seabed, with a flat topography. Therefore, riverbeds are unstable. They “wandered” along the leveled swampy surface, adapting to the mesorelief and the general slope to the north. This is typical of the Yenisei and Abakan also today (Maloletko, 2008: 110). The most mobile was the mouth of Abakan. At present, at the place of its modern confluence with the Yenisei, its width can be traced over a stretch of almost 30 km (Popov, 1977: 17).

When leaving the mountains, many rivers usually form braided beds (Maloletko, 2008: 127). The Abakan bed is composed of a loose substrate—fine sand and sandy loam, i.e. young sediments; consequently, the surfaces of such sediments could be easily eroded, and the water flow could quickly reshape the channels, including the main ones. This was facilitated by the fact that on the plain the Abakan was flooded to a great depth, and thus significant current speeds were created (Popov, 1977: 50), which was noted by the author on the riverbed section near the Sartykov village.

On the Abakan, large sand ridges, moving along the main bed of the river, occasionally blocked the entrances and exits from the secondary channels into the main stream. The river had multiple arms, and constant redistributions of water and sediment flows between the main stream and secondary channels were continuously rebuilding them (Ibid.: 127–128). Probably, this was what happened on the Abakan in 1691–1697, when informants of the voivode Poskochin examined the area near its old riverbed, at the foot of the Western Sayan.

It can be assumed that owing to a large amount of sediment brought by the Abakan from the west to the Yenisei, and the formation of large sand ridges, the Yenisei’s bed was blocked, and the Abakan turned northwards, towards the modern Sorokaozerki tract, with the consequent underwashing of Mount Izykh. This was also the case in the 20th century. A significant number of the ridges have been preserved along the right bank of the Abakan; currently these are preserved in the Peski tract, in the form of river terraces from young sediments near the villages of Matkichik, Ust-Tabat, Koibaly, and Burek sands (all in the Beysky District of Khakassia), as well as sands on Mount Izykh near the village of Sartykov, etc. Remains of sand ridges also occur along the Yenisei, for example, near the villages of Shunery and Nizhnyaya Koya (Shushensky District, Krasnoyarsk Territory), Novoyeniseyka (Beysky District of the Republic of Khakassia), and others. For this reason, in 1936, the flood led to a shift of the Abakan bed within the city, and began to flow into the Yenisei—not upstream Mount Samokhval as before (in the area of the modern poultry farm near the Podsineye village), but downstream of it. A powerful flood in the Abakan city occurred in 1969. In

2011, because of the shift in the Abakan bed, the span of a railway bridge collapsed in the Askizsky District of the Republic. In 2023, another change in the Abakan riverbed occurred: the stream moved and approached boom No. 8 of the South Dam in Abakan.

Conclusions

Thus, on the basis of all the available information, we should conclude that there were several reasons for the relocation of the construction sites of the above forts.

In general, the builders of both forts made the right decisions, having refused to erect fortifications either at the mouth of the Abakan of that time or at the designated place on the Yenisei. Credit must be given to the construction leaders of both objects—the Krasnoyarsk boyar’s son Konon Samsonov and the Tomsk boyar’s son Ilya Tsytsurin (the second Abakan fort), as well as the Krasnoyarsk nobleman Ilya Nashivoshnikov (Fort Sayan), who took responsibility for such important decisions, which had a positive effect on the Russian development of the region, including the creation at a later time of a “chain” of outposts in the south of the Yenisei region. This is also confirmed by the history of the development of the territory of the modern city of Abakan. Already from the beginning of its construction in the 1930s, there were frequent floods. The two most significant of them, being the result of the movement of large sand ridges, took place in 1936 and 1969. However, in the area of Fort Sayan, this did not happen. Even before the construction of the Sayano-Shushenskaya hydroelectric-power station on the Yenisei, according to residents, the water during floods did not reach the territory of the fort, nor the church located on a small hill outside the fort. This means that the sites for the construction of these two objects of Russian fortification of the 18th century, unauthorizedly relocated against the initial plan, were quite well chosen.

Acknowledgement

The study was carried out under the State Assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation for scientific work (Project No. FSUS-2020-0021).