Smartphone intervention to leverage nomadic education in Eritrea: opportunities and challenges

Автор: Tesfu Tekle Okubamichael

Журнал: Высшее образование сегодня @hetoday

Рубрика: Сравнительная педагогика

Статья в выпуске: 3, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The use of smartphone-based pedagogical technology in addressing the educational needs of nomads is an innovative way to address the gaps in access to education among mobile populations. Nomadic populations face significant barriers in accessing sustainable and quality education. Education in Eritrea is provided free of charge at all levels, but in areas with a predominantly nomadic population, enrolment is significantly lower than the national average. The objective of this study is to explore the opportunities and challenges associated with integrating smartphones into the educational process as a promising means of bridging the gap in access to education for nomadic populations and in remote areas. This includes determining the extent to which mobile devices and digital learning content are available to the population; and examining teachers’ readiness to use mobile learning technology. The study is innovative in that it is the first of its kind to provide an initial analysis of the opportunities and challenges of using mobile learning technologies to improve access to education for nomads in schools in Eritrea. A descriptive analysis of data collected through a questionnaire based on interview guides among teachers and learners in nomadic areas is presented. The results show that there is a high potential for using smartphones to overcome inequalities in access to education in Eritrea. Limitations related to teachers’ skills in using gadgets and software, and their readiness to effectively implement smartphone-based learning are identified. Education policy makers are encouraged to develop evidence-based projects aimed at improving teachers’ digital skills.

Smartphone-based learning, education in eritrea, educational inequalities, nomadic education

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148331651

IDR: 148331651 | УДК: 371.3 | DOI: 10.18137/RNU.HET.25.03.P.157

Текст научной статьи Smartphone intervention to leverage nomadic education in Eritrea: opportunities and challenges

Postgraduate at the Department of Theory and Practice of Foreign Languages of the Institute of Foreign Languages, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia named after Patrice Lumumba; Senior Lecturer, Asmara College of Education, Eritrea. Research interests: providing means of equal access to quality education, general education in Eritrea, training teachers to use electronic devices in teaching. Author of eight published scientific works. ORCID: E-mail address:

Российский университет дружбы народов имени Патриса Лумумбы

Introduction. The vision of nomadic education in the contemporary world underscores the importance of providing the nomadic learners with educational opportunities that are inclusive as well as culturally relevant to meet their needs and aspirations. Nomadic education is more advantageous and helps nomadic people to maintain their overall cultural traditions and beliefs. It can significantly improve social engagement and reduce educational disparities when its use is well-planned [8]. A study conducted by K.C. Ibe-Moses held that the most critical strategy for enhancing sustainable development in these societies is to equip them with the skills and knowledge they require to adapt to shifting environmental conditions [11]. Despite improvements in some areas, cross-cutting barriers in relation to access to quality education by these groups still linger. According to a UNICEF report [8], nomadic communities continue to face significant obstacles to accessing an education like remoteness, mobility difficulties, language, and cultural barriers [8].

Eritrea, situated in the Horn of Africa, shares borders with Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, and the Red Sea. It is primarily an agricultural economy on which around 80 % of its population depends. Approximately 65 % out of the approximately 6 million population lives in rural areas, and a portion of the population are nomadic, herd animals with no permanent settlement [7]. The official school age in Eritrea school system is preprimary (KG) 4–5 (2 years), elementary level 6–10 (grade 1–5), middle level 11–13 (grade 6–8) and secondary level 14– 17 (grade 9–12) [15].

To ensure no one is left behind, Eritrea – together with donor partners like UNICEF –introduced the Non-Formal Complementary Elementary Education (CEE) program in 2006–2007, primarily targeting out-of-school children aged 9 to 14 in nomadic communities [20]. Despite these efforts, educational participation rates vary significantly across regions, between urban and rural areas, and among children from nomadic communities. According to a recent Ministry of Education report, national gross enrollment rates stand at 22 % for pre-primary, 115 % elementary, 94 % for middle and 29 % for secondary levels [15]. These disparities are attributed to factors such as scattered settlements, nomadic lifestyles, socio-cultural and socio-economic barriers.

According to a country study report [14], the percentage of out-of-

ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ СМАРТФОНОВ ДЛЯ ПОВЫШЕНИЯ ЭФФЕКТИВНОСТИ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ КОЧЕВНИКОВ

В ЭРИТРЕЕ: ВОЗМОЖНОСТИ И ПРОБЛЕМЫ school primary and middle schoolage children in disadvantaged regions such as Gash Barka, Southern Red Sea, and Northern Red Sea – is alarmingly high. The rates reached 27.39 %, 84.48 %; 24.87 %, 71.40 %; and 20.80 %, 51.62 %, respectively, which significantly exceeds the national average (19 %, 40.88 %). The disparity becomes more evident when compared to the Central Region, which includes the capital city, Asmara, where the percentage of out-of-school children in primary and middle school is notably lower at 5.05 % and 2.75 %, respectively. Furthermore, the rural-urban divide is remarkably evident, with 57.32 % of rural children are out of school compared to 10.6 % of their urban counterparts [15].

One of the strongest and most important functions of Eritrea’s Ministry of Education is its publication of the annual “Essential Education Indicator” report, which assesses the performance of the education system. This report is believed to be highly transparent with the issue of disparities in educational access and performance among schools throughout the country. The latest report indicates that the net enrollment ratio (NER) of the 2022/23 academic year in elementary, middle, and secondary levels was at 81.2 %, 41.4 %, and 20.9 %, respectively and contrasting with the 2015/16 report, 81.2 %, 40.9 %, and 19.0 % respectively, it shows not much improvement [15]. Generally, educational access in Eritrea’s eastern and western lowlands remains challenging due to population dispersion and the remoteness of these areas.

Despite improvements in other areas, significant gaps persist in regions like Gash Barka, Southern Red Sea, and Northern Red Sea – areas primarily inhabited by nomadic and semi-nomadic communities. Therefore, the primary objective of the study was to explore the grounds of whether smartphone devices could be used as an intervention strategy to narrow the gap in nomadic and semi-nomadic pupils’ participation.

Objective of the study. The study is aimed at identifying the opportunities and challenges to using mobile learning technologies to improve nomadic community participation in basic education in Eritrea. The study was guided by the following specific objectives:

-

1. To identify the students’ access to mobile technology devices.

-

2. To analyze accessibility of digital content for learning in Eritrea.

-

3. To unveil teachers’ capacity and acceptance to use mobile learning technologies for teaching.

Relevance of the study. The relevance of the study consists in addressing the information gap in the context of Eritrean mobile learning. Another factor is the contribution that mobile learning can make in the development of Eritrean education, its quality and accessibility. Moreover, digital online and offline mobile learning is growing fast all over the world. Finally, it is necessary to inform policy makers on issues of mobile learning technology innovations in education.

Methods and Materials. This study employed a mixed-methods approach, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative techniques. In order to assist nomadic education in Eritrea, the study aims to investigate the potential and difficulties of deploying smartphone-based interventions. By combining statistical data with in-depth stakeholder insights, a mixed-methods approach enables a thorough understanding of the subject [5]. The study was conducted in selected Eritrean regions which substantial nomadic populations, characterized by high mobility, low literacy rates, and dispersed settlements. Primary data collection included:

-

• structured questionnaires from 200 teachers and 450 students;

-

• semi-structured interview with school administrators and education experts.

To ensure reliable and valid sources were included in the study, secondary data were gathered from:

-

• academic databases using Boolean terminology;

-

• official Eritrean education documents.

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics by employing statistical software (SPSS), and thematic analysis was used to analyze qualitative data.

Literature Review

The rationality of using smartphones in the context of nomadic learning. A new method that could ease the access barrier to education for nomads is the use of mobile learning. By means of mobile learning systems, learners can access learning materials anywhere and everywhere using mobile phones [1]. This notion puts at center stage the concept that mobiles enable flexible learning by providing access to learning resources at any given time and location [4]. Smartphones can play a transformative role in providing education access to nomadic societies. They can host educational apps and platforms that provide access to lessons, videos, and interactive content. These platforms can be tailored to the needs of nomadic communities, offering offline functionality for areas with limited internet connectivity, enabling nomadic societies to access free and open educational resources, such as e-books, videos, and courses. Thus, resources can be downloaded and used offline, making them ideal for communities on the move [19].

Significant goals can be achieved by making educational content on smartphones customized to reflect the languages, cultures, and traditions of nomadic societies, making learning more engaging and relevant [21]. Producing localized and culturally relevant content would mean boosting the confidence of nomadic communities on the use of mobile learning technologies for learning while keeping their distinct culture and lifestyles. Continuous support and guidance for learners can also be ensured as smartphones can connect nomadic students with remote teachers via video calling apps, messaging apps, or online forums [13]. Additionally, F. Hardman, A.M. Sandi, noted that it is also possible with these devices to collect data on educational progress and challenges encountered by nomadic learners. Such data can inform policymakers and improve educational interventions when required [9].

The significance of Smartphone goes to its ability to facilitate collaborative learning through social media groups, messaging apps, or online forums, allowing nomadic learners to share knowledge and support each other. If it is carefully designed and prioritized by policymakers, Smartphone can play a credible role in bridging the gender gap by providing girls and women in nomadic communities with access to education, especially in regions where cultural norms may restrict their access to traditional schooling [22]. Additionally, the innovation in the area of green energy looks more promising. The nature of their life makes many nomadic societies lack access to electricity. However, this problem is no longer an opaque challenge due to the invention of low-cost portable solar power. Thus, solar-powered smartphones and low-cost devices can ensure that education remains accessible even in remote areas [3].

Demographic Characteristics of Students are presented in Table 1.

The age distribution analysis revealed the presence of overage students at both educational levels. This situation is basically the schools in the remote and nomadic inhabited areas are characterized by late age registration and repetition of students in the same class. This is against the official age of schooling at each level [15].

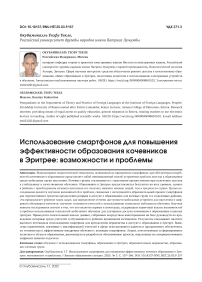

Figure 1 shows the access and type of mobile device by students. To sum up, 82.2 % of the students who took part in the survey have access to mobile technology devices. Therefore, this degree of access to mobile devices would mean the potential to support mobile learning is high.

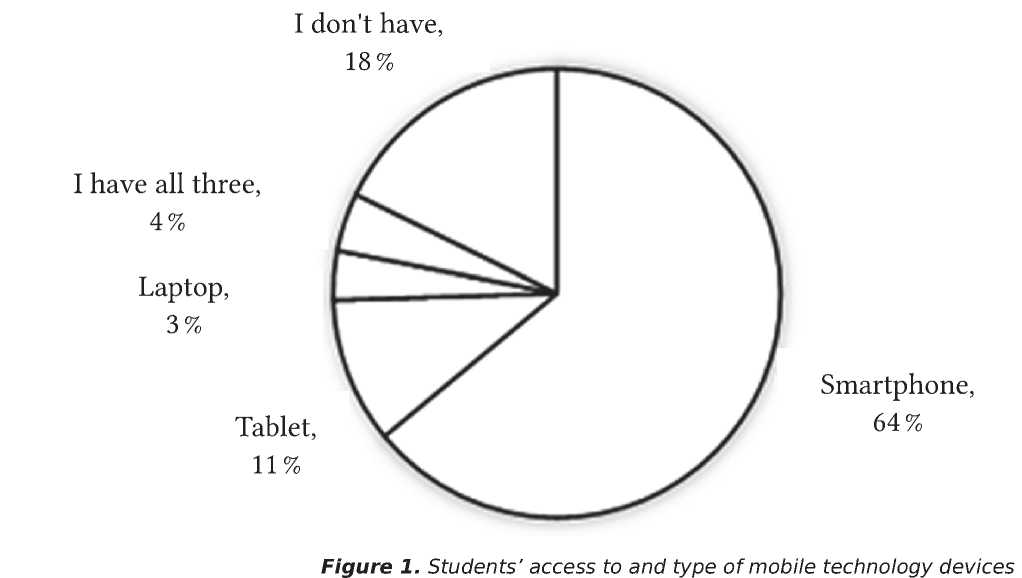

Figure 2 displays the students’ daily average usage of their mobile technology devices. Collectively, the chart shows that more than 50 % of the students engage with their mobile devices for more than 5 hours on a daily average. Therefore, this indicates that there is a possibility of changing this trend into an opportunity for mobile learning with active guidance from teachers.

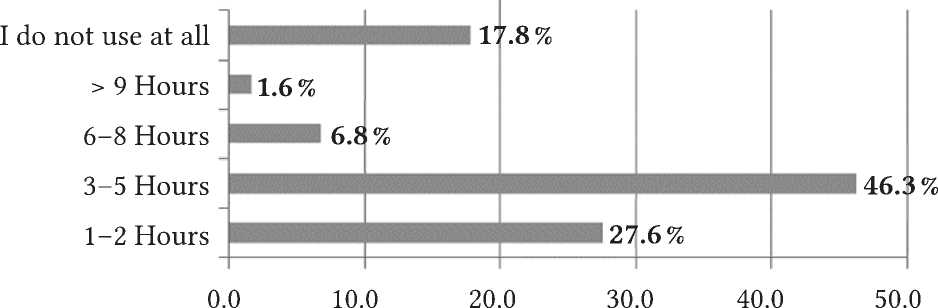

Figure 3 portrays the students’ response on the main purpose for which most students use their mobile technology device. Therefore, as is evidenced from this finding, the inclination of the students to use their mobile technology for education purposes is below average. This situation was also witnessed during the field survey where most of the students were frequently observed busy sharing and watching videos and listening to music. Providing guided activities to be referenced from up-loaded mobile educational applications could enhance the students’ engagement with their mobile devices for educational purposes.

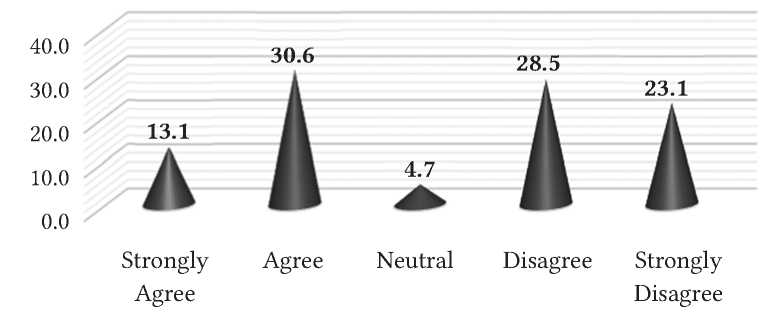

Figure 4 depicts students’ reaction to the statement about motivation from their teachers to use their mobile devices for learning purposes. By contrasting this finding reviles that the implementation of mobile learning to support the education system in Eritrea could be affected negatively. It was also disclosed during the field survey that some teachers were openly arguing the negative impact of mobile devices weighs the positive impact. Moreover, the feedback from the in-depth interviews with school directors and pedagogy heads most teachers are in the position of outsmarted by the students and they do not feel confident applying mobile learning technologies into to teaching learning process. Furthermore,

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Students

|

Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

219 |

51.2 |

51.2 |

51.2 |

|

Female |

209 |

48.8 |

48.8 |

100.0 |

|

|

Age category |

13–14 |

48 |

11.2 |

11.2 |

11.2 |

|

15–16 |

93 |

21.7 |

21.7 |

32.9 |

|

|

17–18 |

192 |

44.9 |

44.9 |

77.8 |

|

|

19–20 |

82 |

19.2 |

19.2 |

97.0 |

|

|

21 & above |

13 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Grade level |

8th Grade |

190 |

44.4 |

44.4 |

44.4 |

|

11th Grade |

238 |

55.6 |

55.6 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

428 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ СМАРТФОНОВ ДЛЯ ПОВЫШЕНИЯ ЭФФЕКТИВНОСТИ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ КОЧЕВНИКОВ

В ЭРИТРЕЕ: ВОЗМОЖНОСТИ И ПРОБЛЕМЫ

Figure 2. Students’ average daily usage of mobile technology devices

majority of teachers do not allow students to bring smartphones to class for the fear of they might take videos of their activities then post on the internet though such violations are very rear in Eritrea.

Figure 5 displays the students’ response on the sources of mobile learning and interactive applications. Therefore, this finding unveils that the main sources of the mobile learning materials are sharing among students with the help of the popular offline sharing application “ Shareit” and upload them from the school’s digital library resource. Moreover, the digital libraries within schools are fed by the National platform “ Rora digital library ” which is taking the initiatives to provide digital learning contents and install offline digital infrastructures in schools especially those in remote areas. Thus, the availability of these digital offline services can boost the opportunity to use smartphone as a strategy to provide educational services to the disadvantaged nomadic societies in Eritrea.

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of teachers who participated in this study. The table discloses that at least half of the teachers who took part in this study have less than five years of teaching experience. This situation would mean that they are fresh minded to accept any kind of training on the area of mobile assisted teaching technologies.

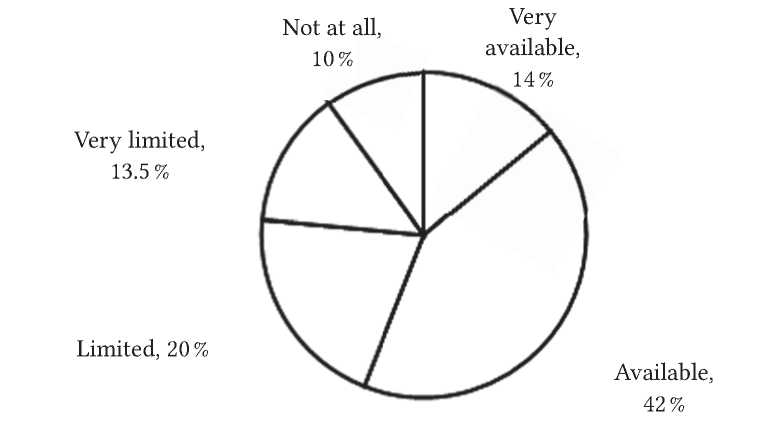

Figure 6 shows the teachers’ response on the degree of digital learning materials availability for educational purposes in their schools. The graph reveals that the availability of digital resources in schools is moderate. Moreover, the report from the in-depth informants indicates that schools have relatively enough digital content like video, audio-visual equipment, and digital texts which can support adoption of mobile learning. Offline digital educational resources and interactive learning applications are mostly offered by Rora Digital Library. However, the majority of the teachers do not have the required skill and confidence to use these resources for teaching. Additionally, like the students, the teachers are also seen usually sharing and watching videos not related to educational purposes.

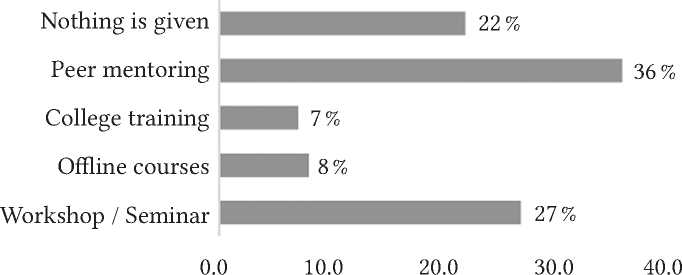

Figure 7 shows the teachers’ reaction to the provision of training or professional development opportunities for teachers to enhance their capacity to use mobile learning technologies. As can easily be traced from the graph, most teachers had no chance of professional development opportunities on digital literacy and skill. This lack of training could hamper effective implementation of smartphone intervention to fill the gap in education provision and outcome. According to the information from Mr. Kiflom Michael, director of Rora Digital Library, though it is limited to the massive demand on ground, training is provided with close cooperation between their digital library and the ICT department of the Ministry of Education.

Discussion. The discussion is outlined under two overarching subtopics: Potentials and challenges.

Potentials for Smartphone Intervention

Access to Mobile. The results indicate that there is a greater proportion of students (82.2 %) who have mobile technology devices, where smartphones are the most common (64 %). Such increased access signifies great possibilities for the implementation of mobile learning programs. Nomadic schools can upload into the student’s smartphone interactive learning contents and mobile game apps which respect the nomadic societies life style [21]. Surprisingly, there are no noted differences in the access to mobile devices among male and female students. This is a positive result as it indicates that m-learning programs can be developed without increasing gender inequalities [22]. Hence, given these findings, mobile phones can be utilized as transformative educational tools that would provide students from remote and nomadic areas with access to educational materials regardless of their physical location.

Daily Attendance. Approximately half of the students spend more than 5 hours a day on their portable devices. This level of screen time certainly has the potential to support mobile learning. It is possible to motivate learners slowly to shift their purpose of using mobile devices from entertainment to education [17]. The use of mobile technologies to a greater extent presents opportunities to integrate digital education into students’ lives. Besides, students should work to make them understand the role of mobile devices in their learning by means of mobile projects and assignments, and interesting educational interactive computer software [18].

Digital Learning Materials. The offline digital resources such as those from Rora Digital Library serve as a great base for mobile learning initiatives. Since most students receive their learning materials through school or via offline sharing applications like “ Shareit ”, there is a chance to broaden this system to enhance the accessibility of educational resources. The existence of digital libraries and offline digital content in schools will play a big part in closing the educational gap in the remote nomad areas. The national platform RORA Digital Library [19], is a promising agency in assuring the continuity of offline mobile learning resources and it is up to the schools to use this opportunity to improve the learning outcome of their students.

The Readiness for Training: in Learning Activities Within the Teachers’ Demographic Profile, a major part of the respondents’ age distribution is considerably younger as shown by 61 % being below 30 years and 27.5 % younger than 40 years. This profile indicates an understanding workforce that would accept new technologies given that proper education is offered. Therefore, in order to increase their willingness to adopt mobile learning technologies a targeted professional development initiative would be needed [10]. Additionally, most teachers hold at least bachelor’s degrees (65.5 %), which suggests that they possess the academic background

ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ СМАРТФОНОВ ДЛЯ ПОВЫШЕНИЯ ЭФФЕКТИВНОСТИ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ КОЧЕВНИКОВ

В ЭРИТРЕЕ: ВОЗМОЖНОСТИ И ПРОБЛЕМЫ

Figure 4. Students’ responses if teachers motivate them to use mobile in class

Have no access, 12.9 %

Download from

Buy from internet cafes, 2.8 %

internet, 4.4 %

Share from friends, 53 %

Figure 5. How students mostly get mobile learning applications

Upload from school, 26.9 %

Table 2

Demographic characteristics of Teachers

|

Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

145 |

72.5 |

72.5 |

72.5 |

|

Female |

55 |

27.5 |

27.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Age category |

Below 30 |

122 |

61.0 |

61.0 |

61.0 |

|

31–40 |

55 |

27.5 |

27.5 |

88.5 |

|

|

41 & above |

23 |

11.5 |

11.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Educational Level |

Diploma in education |

58 |

29.0 |

29.0 |

29.0 |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

131 |

65.5 |

65.5 |

94.5 |

|

|

Post-graduate diploma |

11 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

Teaching Experience |

< 5 years |

101 |

50.5 |

50.5 |

50.5 |

|

6–15 years |

75 |

37.5 |

37.5 |

88.0 |

|

|

16–25 years |

16 |

8.0 |

8.0 |

96.0 |

|

|

26–35 years |

8 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

200 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

– |

|

Very limited, 13.5 %

Limited, 20 %

Available, 42 %

Not at all, 10 %

Very available, 14 %

Figure 6. Digital learning materials availability for learning

Figure 7. Professional Training opportunities provided to teachers to enhance their capacity to use mobile learning technologies

necessary to comprehend and utilize mobile learning tools.

Challenges Regarding Smartphone Intervention

Trends in Engagement. Nevertheless, despite the nearly universal access, the research shows that students are more likely to use mobile devices for entertainment purposes (45 %) rather than academic ones (38 %). This comment highlights the need for adequate control and visualization which assists in guiding through the students’ use of mobile technologies in education [2]. The potential to serve more educational purposes is significant as 46.3 % of students use their gadgets for a minimum of 3–5 hours per day. The patterns could be altered fundamentally with the introduction of well-crafted captivating instructional software together with other teachers’ activities. Moreover, developing localized digital learning contents which reflect the languages, cultures, and traditions of nomadic societies [21], could capture the drive of the students for more engagement in their own learning.

Skepticism and Resistance from Teachers. It is of great concern that, with a medium level of resources available, there is a good proportion of learners (51.6 %) who suggest that their teachers do not find it worth- while motivating them to use mobile learning. In this issue a group of school directors and pedagogical leaders who were interviewed elaborated that teachers are concerned about the adverse effects of mobile devices and some of them feel technologically outsmarted by their students. This belief comes from poor digital literacy and lack of confidence in using mobile devices for teaching. Moreover, the fear of allowing smart phones into the class because of their misuse is responsible for stagnation of mobile learning resources. For instance, many teachers usually report that students who sit at the back in

ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ СМАРТФОНОВ ДЛЯ ПОВЫШЕНИЯ ЭФФЕКТИВНОСТИ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ КОЧЕВНИКОВ

В ЭРИТРЕЕ: ВОЗМОЖНОСТИ И ПРОБЛЕМЫ the classroom share music and videos while the teacher is busy with teaching. This could make classroom management difficult and less effective teaching.

Inadequate Training. With the addition of offline materials, there are still some resources materials for training the teachers which appear to be at a standstill. Regarding this, the survey showed that 36 % of teachers admitted that they used fellow teachers to train them to acquire basic skills while 22 % had no chance for further training during digital literacy. These findings point to a serious need for sufficient formal pedagogy training which incorporates the use of mobile devices [16]. Despite efforts by the collaboration of the Ministry of Education’s ICT Department and national organizations such as Rora Digital Library to offer training, the current provision is insufficient to meet the demand. The lack of training on how to effectively use mobile devices for teaching could result in poor implementation and limited impact of mobile learning initiatives [6]. Therefore, addressing these concerns through targeted training and capacity-building programs which accommodate a variety of local contexts is essential to fostering a supportive environment for m-learning.

Policy and Practice. The results of this study suggest that policymakers and educators in Eritrea should take several factors into consideration. To begin with, the notable mobile penetration among students offers a special chance to tackle the educational imbalance in the far-flung remote and nomadic areas of the country. However, this promise can only be achieved if teachers are sufficiently trained and supported to devise m-learning plans [12]. Moreover, Rora Digital Library is a good start [19], but more offline resources and training are needed. Finally, although small, closing the gap between students with and those without access to mobile phones is essential for equal educational opportunity for all students.

Conclusion. The results of this work highlight both the great promise and the formidable difficulties con- cerning the adoption of mobile learning in the nomad populated areas of Eritrea. Thankfully, there is much to celebrate in the form of mobile device ownership and the heavy engagement of students parallels access to these devices. In addition, the existence of offline learning materials and the young teaching staff further supports the possibility of mobile learning implementation. However, challenges such as the limited use of mobile devices for educational purposes, teacher resistance, and lack of training must be addressed for successful implementation.

Recommendation for Future Research. Despite the reliable information this report has, it still has flaws that must be addressed. The results might not be useful outside of the context in which they were gathered, since the sample was limited to the nomadic populated areas of Eritrea. It might be worthwhile investigating the long-term effects of mobile-learning interventions on students and consider how to address teachers’ resistance to newer technologies.