South Russian settlers of Western Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, based on archival documents and field studies

Автор: Fursova E.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In cultural terms, as compared to many other Russian groups, the South Russian (Kursk) settlers of Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries were a distinct group, having their own traditional culture but usually no compact settlements. In this work, for the first time, on the basis of the State Archive of the Kursk Region, the ethno-cultural composition of Siberian settlers from that region is examined. Attitudes of South Russian peasants of the post-Reform era to migration are analyzed, reasons underlying their “wanderlust” and their reflection about relocation and ethnic identity are explored. Documents at the State Archive of the Tomsk Region, and the findings of my fi eld studies in 2014– 2018 pertaining to the Siberian stage in the history of Russian “Yuzhaks” (Southerners) suggest that their priority was to live side by side with Ukrainian settlers, as they had used to do in their homeland. The reason is that the key role in the early 20th century migrations was played by Russian-Ukrainian frontiersmen—people of “no man’s land”. At the time of migration to Siberia, those living in the southern Kursk Governorate were Russian Old Believers, Southern Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians (Little Russians), Russian Cossacks, and “Cherkassians” (Ukrainian Cossacks). The latter preferred to live apart from others, even within a single village. Archival documents and findings of field studies in the Anzhero-Sudzhensky District of the Kemerovo Region, and in the Topchikhinsky and Kulundinsky Districts of the Altai Territory demonstrate that Southern Russians were situationally identical to Ukrainians, as evidenced, for instance, by the frequent shift of surname endings from “-ko” and “-k” to “-ov” and vice versa, depending on migration plans. A conclusion is made that the ethnic diversity of migrants from the Kursk Governorate, the situational equivalence of Eastern Slavic groups in Siberia, as well as marriages with Russian old residents and Ukrainians, were key factors in the formation of local Siberian variants of the South Russian culture.

South Russian settlers, Kursk Governorate, Russian-Ukrainian frontier, factors of migration, Western Siberia, situational identity

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146793

IDR: 145146793 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.3.121-130

Текст научной статьи South Russian settlers of Western Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, based on archival documents and field studies

It is quite obvious that only the study of the history of the ethnic/ethno-cultural community of people in time and space makes it possible to come to a conclusion about the stability or, conversely, the instability of its differential features. Mass migrations of South Russian peasants, based on a comparison of materials deposited in the archives in the places of exit and settlement, have hardly been studied. Siberian peasants—migrants from the southern Russian-Ukrainian border provinces, as well as their descendants—have not yet been the objects of special ethnographic research. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the “Yuzhaks” or, as they were called in Siberia,

“Khakhly” culturally occupied an intermediate position between Russians and Ukrainians.

Migration to Siberia was a consequence of the Great Reform of February 19, 1861; it became an exceptional global example of mass movement of the population within the state (Popov, 1911: 249). The construction of the Siberian railway was a turning point in the resettlement business: from 1895, the resettlement began to grow rapidly and culminated in 1908 (Ibid.: 255). How did such a large-scale dispersion of the Russian people within the boundaries of their state (the Russian Empire) affect their ethnic identity, what were the directions of its transformation? We venture to suggest that the resettlement was one of the factors not only for the repopulation of the “Great Outskirts”, but also for the actualization of the ethnic identity of the settlers, the emergence of its new forms in the everyday life of the rural population of this period.

The source base of this article has been made up of legal and regulatory documents of various origins, as well as records management materials of governorate (Kursk and Tomsk) institutions. The archival materials identified by this author make it possible to reveal the obvious and hidden reasons for the move, the structure of migrating families, the reflection of Russian/Ukrainian identity in the unstable situation of mass migrations to Siberia, as well as the relationship of the rural population with the official authorities in the territories of exit and in places of arrival. During the research, we used the materials of archives located both in the Asian and European parts of Russia—the places of exodus of the southern Russians. In the State Archive of the Kursk Region (GAKO), 43 cases were worked out; in the State Archive of the Tomsk Region (GATO), there were 40; in the State Archive of Anzhero-Sudzhensk, Kemerovo Region, there were 51 cases. Local history literature was used, including pre-revolutionary publications, from the collections of scientific libraries in the cities of Kursk, Stary Oskol, and Sudzha, Kursk Region.

The methodological basis of this study was formed by historical-ethnographic and historical-situational approaches. Content analysis of texts from archival sources was used as an analytical method. We are of the opinion that the study of the nature and motives of colonization movements allows us to take a fresh look at the nature of ethnocultural formations and the mechanisms of interethnic relations. In this regard, it seems important that Russian culture is characterized by the principle of a complementarity of cultures—mobility and rootedness, i.e. such a combination that fosters in a person both love for a “little homeland” and at the same time free identification, i.e. does not contradict spatial mobility (Krylov, 2009: 276).

When working with materials related to South Russian settlers, it is important to take into account that this population was not homogeneous in ethnocultural terms. In different historical periods, the southern steppes were settled by Russian and nonRussian migrants from Northeastern Russia, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, etc. Since ancient times, the southern territories of Russia (former Orel, Voronezh, Kursk governorates) were the scene of clashes between the Eastern Slavs and nomads (Khazars, Pechenegs, Polovtsy (Cumans), and Tatars) and were known as the “wild field”. At the end of the 15th century, the royal clans of Vorotynsky, Odoevsky, Belsky came here, with their entire estates, across the Lithuanian border. Later, the core of the steppe settlers were service people. In the second half of the 16th century, Cossacks came in the service of the Moscow sovereign (Bagalei, 1887: 140). In the 16th–17th centuries, during the struggle of the Moscow State with the raids of nomads, the “wild field” was repopulated, and the ethnographic features of the population took their shape. Among the settlers there were many fugitives, like peasants from the territories of the future Tula, Moscow, Kaluga, Kostroma, Vladimir governorates, as well as villagers fleeing the “Lithuanian ruin” (Chizhikova, 1998: 31, 32). Simultaneously with the free migrations, the governmental repopulation of these lands went on: migrants from Lithuania were sent here for military service (Bagaley, 1887: 369). Ethno-cultural composition of the population of Southern Russia was formed, in addition to service people (odnodvortsy), free “walkers”, and serfs resettled from other places, also by the residents of villages that survived from the time of the Tatar raids, these villages being located away from Tatar roads, in forest areas, and being therefore not subject to destruction (Ibid.: 201–237). According to the data of the First General Census of Population of 1897, in the Kursk Governorate, Russians made up 77.29 %, and Ukrainians 22.26 % (Chizhikova, 1998: 34).

Let us turn to the analysis of archival data on groups and individual families of the Kursk settlers, whose numbers in the early 20th century surpassed many other “seekers of a better life” in Siberia.

Resettlement from the Kursk Governorate

In the 1860s–1870s, according to the materials of the “Kursk Governorate Board for Peasant Affairs” (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, Vol. 1, fol. 41, 150, 151, etc.; Vol. 2, fol. 40, 76, 168, etc.), migrations from South Russia to Siberia were not popular. At this time, the peasants, including the odnodvortsy *, most often filed petitions for moving to the nearby Astrakhan, Yekaterinoslav, Orel, Poltava,

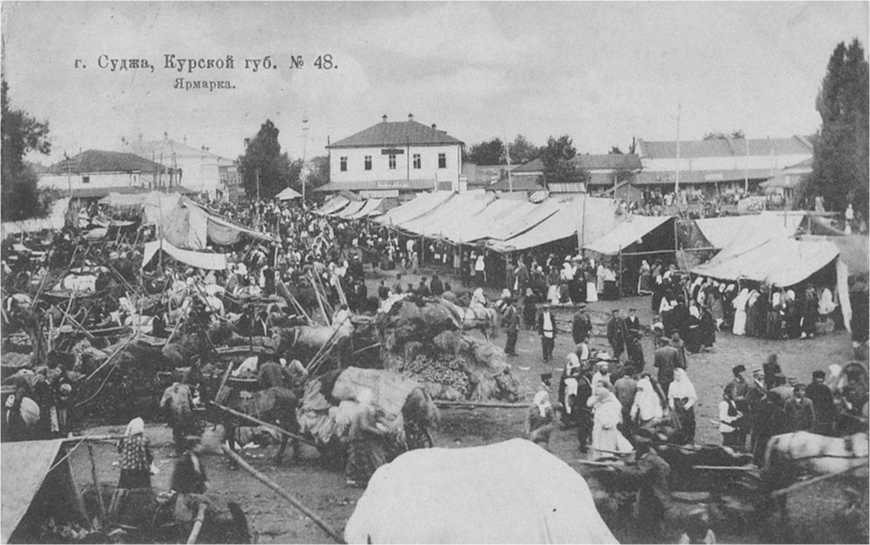

Fig. 1. Fair in the city of Sudzha, Kursk Governorate. Postcard (.

Stavropol, or Kharkov governorates. In the European part of the country, the problem of land shortage was acute for peasant farms, but the possibility of solving it through the development of Siberian territories was not discussed (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, Vol. 1, fol. 41, 150, 151, 155, 341, etc., Vol. 2, fol. 40, 76, 168, 294, 297, etc.). The list of state-owned peasants of the Timsky District and the villages of Vyazovoe, Chuevo, and Ukolova of the Starooskolsky Uyezd, who expressed in 1861 a desire to move to Western Siberia, has been preserved (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, Vol. 1, fol. 41). There are few materials on the resettlement of temporarily liable peasants*, for example, P.G. Zhidovtsev, P.N. Mozgovoy from Grayvoronsky Uyezd, etc. (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, Vol. 1, fol. 411). There are single references to the exile of peasants to Siberia by the decision of rural societies, for example, A. Paukova, the “house serf” (domestic servant) of the Shchigry landowner P.A. Yudin, was exiled “for bad behavior” (1861–1863) (Ibid.: Fol. 41). Among various kinds of petitions, there are documents about those who wished to return, with the mention of Tobolsk and Yenisei governorates.

A completely different perception is created by archival materials of the 1880s–1890s. There are numerous cases and lists of people who wanted to move to Siberia. By the end of the 1890s, in all cities of the Kursk

Governorate—Kursk, Belgorod, Dmitriev, Putivl— and especially in the uyezds, there was an increase in population, both officially Orthodox and Old Believers (Kursky and Belgorodsky uyezds, Korocha, Miropolye, Fatezh, Shchigry, etc.) (O dvizhenii naseleniya…, 1904: 68). It is no coincidence that it was at this time that the issue of scarce land arose: it was not enough not only for family divisions, but also for undivided families (i.e. parents and grown-up children), as evidenced by the numerous cases related to the disputes on this topic (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, D. 8608, 3913).

The move was planned by the peasants of the southern uyezds of the Kursk Governorates—Belgorodsky, Novooskolsky, Sudzhansky, Timsky (Fig. 1). According to the data on the resettlement movement in the governorate for 1899, among those who went to Siberia, residents of the Timsky Uyezd predominated (1165 souls of both sexes (s.b.s.)), and almost all of them moved to the Tomsk Governorate (the number of returnees is negligible). Peasants of Starooskolsky, Putivlsky, and Kursky uyezds also settled mostly in the Tomsk Governorate. In contrast, people from the Sudzhansky Uyezd, who went to the Tomsk Governorate, mainly returned to their places of origin. Those who left Novooskolsky Uyezd (1042 s.b.s.) settled in the Yenisei and Tomsk governorates in approximately equal proportions. Natives of the Rylsky Uyezd preferred the Yenisei region (Ibid.: 78).

State-owned peasants predominated among the applicants for the move. Even though the country was going through the agrarian reform of P.A. Stolypin, and pursuing a policy of mass migration of residents of European Russia to Siberia, the permission to move to other regions of the Russian Empire was given by the local authorities not to everyone. In 1887–1889, three out of twelve families that applied to leave the village of Velykaya Rybitsa, Miropolskaya Volost, Sudzhansky Uyezd (hereafter only the volosts of the Sudzhansky Uyezd are indicated), were denied, apparently due to the fact that they had land plots sufficient for the livelihood of families in their homeland (6, 3, and 9 dessiatins, respectively) (GAKO. F. 68. Inv. 2, D. 3672, fol. 7, 25, 78–83). The request of state-owned peasants G.A. Golentovsky, S.A. Golentovsky, S.V. Golentovsky, and A.R. Golentovsky (village of Fanasyevka, Ulankovskaya Volost) was declined (Ibid.: Fol. 113– 115). Applications to leave were submitted by fifteen families from the village of Vishneva, Belovskaya Volost, but almost half of them were denied with no explanation (Ibid.: Fol. 19, 66–70).

Documents have been preserved recording a request to move from the state-owned peasants of the village of Sukhodol, Belovskaya Volost (Ibid.: Fol. 116–119). The request of the widower Ivan Egorovich Kostin, who lived in the village of Krivitskiye Budy, Cherno-Oleshanskaya Volost, together with six children, the wives of two older sons, and two grandchildren (a total of eleven people, who had five dessiatins of land) was granted (Ibid.: Fol. 120–121).

From the peasants, including Old Believers, of the settlement of Zapselye, Miropolskaya Volost, a request to leave was filed by the following: V.V. Logvin, I.S. Svetlichny, Y.S. Roenko, S.Y. Shcherbina, I.S. Roenko, F.P. Mikhailichenko, I.G. Marnichenko, P.M. Kamenko, I.A. Pleskachev, V.K. Poddubny, temporarily liable peasant K.P. Galaika (Ibid.: Fol. 20, 21, 71v–74). Out of eleven families, only the family of P.M. Kamenko, with two small children and four dessiatins of land, was denied. Among the peasants who applied in the village of Tolsty-Loug, Daryinskaya Volost, there were probably also Old Believers, if we take into account their names: Luppa Ivanov Pugovkin, Moisey Mikhailov Zherelov, Evstraty Timofeev Lyakhov, Ivan Ivanov Vasilitsky, Pantilimon Pavlov Tkachev, Leonty Savelyev Shesterikov (soldier), Yakov Platonov Novikov, Yakov Alekseev Shesterikov (Ibid.: Fol. 88–91). Out of thirteen requests for relocation, only six were satisfied, including the petition of a soldier and his family, who owned four dessiatins of land.

Former serfs also applied for resettlement, for example, those previously owned by landowner Mikhail Kolminov (village of Vasilyevka, Miropolskaya Volost) (Ibid.: Fol. 75–77). All received positive responses. Among those who wanted to leave their place of residence were the former peasants of the landowner Sergei Dinisov Korogodov from village of Ivanovka-Rubanshchina,

Zamostyanskaya Volost (Ibid.: Fol. 26, 63v–64). The former serfs of the landowner Markiza Tertsiya also wished to move: the families of G.G. Surzhenko, Y.Z. Dekhtyareva, I.E. Shevchenkova (village of Knyazhy, Zamostyanskaya Volost) (Ibid.: Fol. 84–85). All were denied with no explanation.

A separate list of former “ house serfs ” from various villages of Ulankovskaya, Rzhavskaya, and Malo Loknyanskaya volosts, Sudzhansky Uyezd, has been preserved, who petitioned for their resettlement to the Tomsk Governorate. The former house serfs of the landowner Lieutenant Ivan Nikolaevich Zelenin also filed the petition (Ibid.: Fol. 24). Their property included, as a rule, a hut with some yard structures, sheep, and sometimes a cow. Former house serfs did not own horses (Ibid.: Fol. 57v–58).

For resettlement to Siberia, it was required not only to submit an application, but also to provide information on arrears, funds received from the sale of the applicants’ property, etc. (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 2, D. 4971, fol. 155). One of the preserved complaints, dated 1871, was filed by a non-commissioned officer, V.F. Grazhdankin, to the Ragozetskaya Volost government, which forbade the resettlement of his relatives, peasants, from Repets, a village in Timsky Uyezd, to the Tomsk Governorate (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 1, Vol. 1, fol. 297). When making decisions on resettlement, the commission probably took into account the size of the land allotment per capita (family member), although this indicator was not decisive either. The peasants appealed to the Governor of Kursk with a request to give an answer as soon as possible to the resettlement petition filed a year ago to the Tomsk Governorate, “so that we do not live in poverty with our families and are not left without subsistence” (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 2, D. 3672, fol. 7r–7v).

According to data for 1890, “on arrears, time of their accumulation, and the means of petitioners, attributed to the peasants of the Belgorodsky Uyezd of the Muromskaya Volost (now the Belgorod Region – the Author ) applying for resettlement to the Tomsk Governorate” (GAKO. F. 68, Inv. 2, D. 4971, fol. 1), there were few arrears— mostly small amounts of zemstvo dues. The money that the petitioners were supposed to receive from the sale of their property ranged from 50–60 to 500–600 rubles.

The archival materials reflect obvious and hidden reasons for the resettlement of the Kursk peasants in distant Siberia, data on the composition of the families of “seekers of happiness”, etc. The GAKO stores many appeals to “Mr. Indispensable Member of the Belgorodsky Uyezd Board for Peasant Affairs of the Kursk Governorate” of 1890, from peasants, about “permission to resettle in the Tomsk Governorate and legal assistance” (Ibid.: Fol. 3–26). For example, the Maslov peasants Petr Andreev, Petr Nikiforov, and Ivan Mikhailov (as part of a group of 48 families) wrote about their desire to move with three families “in number of nine males and thirteen females to the lands of the Cabinet of His Majesty, located in the districts of Barnaul, Biysk, and Kuznetsk… in which there will be free land” (Ibid.: Fol. 3). The patronymics of the Maslov settlers are different; apparently, they were not brothers, but relatives of varying degrees of kinship or namesakes. All the 48 families indicate the same reasons for resettlement: “we have the smallest amount of land, fringe earnings are insufficient and meager owing to the populousness”. However, many of the people named in this list later refused to resettle (Ibid.: Fol. 93, 94, 90, 105, 106, 107). One of the refusal letters of 1891 from the peasants of the above list has been preserved: “…we all unanimously respond that we do not want resettle in the designated governorate because of the lack of funds, and humbly ask the Government not to attach any importance to our petition for resettlement, in which we sign: Maslov, Zemlyachenko, Gashchenko, Bezbenko, Trofimov, Lozin, Ishchenko, Danilov, Danshin” (Ibid.: Fol. 108). In this file, there is no information about whether these peasants applied again for permission to resettle in Siberia. Noteworthy, in the departure lists, the Russified surnames of peasants are indicated (for example, Gashchenko became Gashchenkov, Ishchenko Ishchenkov, etc.), but in the documents with a refusal to move, the former Ukrainian surnames are given.

Petitions for resettlement in Siberia came from the peasants of the village of Arkhangelskoye, Belgorodsky Uyezd, Muromskaya Volost—Stefan Ivanov Zemlyachenko, Nikita Semenov Sukhoivanov, Fedor Maksimov Zemlyachenko, Sergiy Ivanov Gashchenkov, and others. In all the appeals, the text was drawn up uniformly: “We, the aforementioned peasants, consisting of twelve families of 37 males and 30 females, have a desire to move to the Tomsk Governorate, to the lands belonging to the Cabinet of His Majesty, located in the districts of Barnaul, Biysk, and Kuznetsk, that is, in those that will be free for settlement. Moreover, we undertake to pay all duties for the Land we receive, in accordance with the existing Law. At the same time, we explain that we peasants from our landowner Count Gendrikov received as a gift the land of 22 and 1/2 sazhens for each person entered in a census list… For the reasons stated, namely, the extreme lack of land, meager earnings, and great populousness, inconvenient for farm management, we all humbly ask Your Highness to make an order for legal assistance in allowing us to transfer us to the Tomsk Governorate…” (Ibid.: Fol. 4r–4v). Similar petitions, written as a blueprint, also came from other peasants.

Applications on resettlement in the Tomsk Governorate were submitted by the residents of many other places in the Belogorsky Uyezd, Muromskaya Volost—the village of Nelidovka (often mentioned are the names of Kleopov, Shcherbakov, Goduev, Lazarev, Kudryavtsev, Markov, Shuvaev, etc.), village of Mazikino (Pisarev,

Sharapov, Shlyakhov, Rastvortsev, Mazikin), village of Shlyakhova (Shlyakhov, Orekhov, Kazmin), village of Melikhovo (Lazarev, Gridchin, Podporinov, Uvarov), village of Sheino (Shein, Lazarev, Merzlikin, Ogurtsov), village of Dalny Igumnov (Shekhanin, Panov, Ryzhikov, Morozov, Shumov), etc. (Ibid.: Fol. 10–13). As we see, in these villages, applications were submitted mostly by the people with Russian surnames, ending with “-ov”. In the settlement of Novaya Tavolzhanka, Belgorodsky Uyezd, Shebekinskaya Volost, families with Ukrainian surnames filed documents on the resettlement—Shchelkun, Kutsenko, Gerashchenko, Shelest, Sheika, Kolenko, Kabluchka, Smyk, Dzyuba (?), etc. (Ibid.: Fol. 27). Judging by the names, among those who wanted to move from the Kursk Governorate, there were many Ukrainians. However, as noted above, the situation was not so clear-cut. For example, a resident of the village of Staraya Tavolzhanka, originally listed as Smyk, later began to register himself according to the Russian tradition as Smykov (Ibid.: Fol. 29, 49); Ovcharenko from the village of Churaeva later turned out to be registered as Ovcharenkov; alternating are also the surnames Nikitchenko(v), Boglchenko(v), Danilchenko(v), Furs(ov), etc. (Ibid.: Fol. 27, 29v, 36, 37, 39, 40, 41, 42).

In 1889, large groups of peasants from the Belgorodsky Uyezd declared the desire to change their place of residence: the village of Titovka, Shebekinskaya Volost – 13 families (43 males and 39 females), settlement of Bezlyudovka – 83 families (225 males and 210 females), etc. Residents of the Sabyninskaya Volost also tried to leave: the settlement of Raevka (Denisov, Timofeev – 10 s.b.s., Gamanchenkov – 8 s.b.s.), the settlement of Olkhovaty (Emelyan Ivanov Lukin – 7 s.b.s.), the settlement of Znamensky (Semen Kazmin Kirzunov – 6 s.b.s.); the village of Bezsonovka (Bezsonovkaya Volost) (Kovalev, Soloviev, Vlasov, Pryadkin, Bezpyatov, Seleznev, Shevchenko, etc.); the village of Igumenka (Starogorodskaya Volost), etc. (Ibid.: Fol. 37, 54, 56, 58, 71, 72).

Individual petitions usually came from families with many children, who had grown-up sons and at the same time possessed extremely small allotments of land. As an example, we cite the fragment of submission by I.D. Timofeev: “…a petition addressed to His Excellency Mr. Governor of Kursk from the family of Ioann Denisov Timofeev. My family consists of: me, the petitioner, Ioann Denisov Timofeev, 45 years old, my wife Evdokiya Lukyanova, 42 years old, children sons Roman, 23 years old, Ioann, 21 years old, Semen, 18 years old, Prokofy, 4 years old, Afanasy 1/2 years old, daughters Anna 8 years old, Maria 6 years old, Roman’s wife Ekaterina Fedorova 20 years old; in total, ten s.b.s. We owned land in the amount of 2 and 3/4 dessiatins of soul land-right” (Ibid.: Fol. 73). Owing to the “lack of land”, a resident of the settlement of Znamensky, Kirzanov, the father of three adult sons, filed a petition: “…me, the petitioner, 60 years old, my wife Marfa Vasilyeva, 55 years old, sons Stefan, 21 years old, Fedor, 19 years old, Pavel, 16 years old. Stefan’s wife Alexandra Nikiforova, 20 years old; in total, six s.b.s. We owned land of 1 and 1/10 dessiatins” (Ibid.: Fol. 76). However, as follows from some documents, the move could be explained by the desire not only to strengthen their financial situation, but also to protect their sons from military service.

Let us look at the preliminary stages of preparation for resettlement. Correspondence between the governor of Kursk and the manager of state property in Western Siberia has been preserved, from which it follows that local authorities took seriously and responsibly the issue of resettlement. In 1891, from the Tomsk Governorate a letter was sent to the governor of Kursk, with the following content: “On behalf of the Minister of State Property, Deputy Minister of State Secretary Vishnyakov, on whose permission the submission of Your Excellency dated July 21 of this year No. 6601 was communicated, suggested that I allocate, for the use by 315 families of peasants of the Belgorodsky Uyezd of the Kursk Governorate, the state land from the plots of the Tomsk Governorate intended and suitable for this purpose (January 28, 1891, Omsk)”. An urgent request was made to provide nominal lists of the aforementioned settlers, indicating the place of their registration, the number of male souls in their families, and also “what category of rural inhabitants they belonged to at home, that is, whether they were the former property of landowners or state-owned peasants” (Ibid.: Fol. 79r–79v). The letter also reported on the allotted lands and on the need for registration: “I consider it necessary to add that state-owned plots in the Baimskaya Volost of the Mariinsky District of the Tomsk Governorate have been allocated for the placement of the above-mentioned settlers, and that upon arrival in the Mariinsky District, the settlers should contact the general foreman, Court Counsellor Rozinov” (Ibid.: Fol. 79v). Further, a request was expressed that “the exit certificates issued to the migrants should be kept by them until they arrived at the places of new settlement and handed over only to the official of the resettlement detachment…” (Ibid.). In the second half of May 1891, with the opening of navigation along the rivers of Siberia, it was planned to send migrants with the first steamboat from Tyumen to Tomsk, or by land from Tyumen along the Siberian highway through Tomsk to Mariinsk, located near the Baimskaya Volost (Ibid.).

The issued certificate for the right to resettle limited the time of departure for the peasants. This allowed the authorities to regulate migration flows in order to avoid unnecessary influxes of the population. The time of use of the exit certificates was also limited. The order of the Kursk governor stated: “if somebody fails to use his/her travel permit within 2 months from the date of issue, it will be taken away” (Ibid.: Fol. 81).

From the above documents, it can be seen that sometimes the Kursk people refused to be resettled. The peasants explained this decision by the fact that they did not immediately understand that they had to move at their own expense. Here is a typical letter with the justification of refusal to the Shebekinskaya Volost board: “…at present, we do not want to move to that governorate, and also to accept permit for resettlement, because resettlement was allowed to us not at the expense of the treasury, as we supposed, but at our own expense, with only the reduced fare for travel by rail, in witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand. February 12, 1891” (Ibid.: Fol. 109–120).

Nevertheless, quite large groups went on a long journey, as was stated in reports to the authorities. Here is a message about the departure of families from their native places in the Belgorod region: “…On the 16th of this May, migrants left their homeland to settle on the state lands of the Tomsk Governorate of the Mariinsky District of the Baimskaya Volost, according to the permission of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the peasants of the Novaya Tavolzhanka settlement of the Shebekinskaya Volost of the Belgorodsky Uyezd in number of 21 families, namely: Fedor Ivanov Neporozhny, Nikita Alekseev Kolenko, Alexei Ivanov Kolenko, Kozma Petrov Dzyuba, Ivan Kozmin Shevkun, Fedor Dmitriev Fursa, Sidor Fedorov Kabluchka, etc.” (Ibid.: Fol. 121).

Parents with adult children, as well as young and newborn children, one-, two-, and three-generation families, went to new lands. However, according to archival documents, not all migrants reached their destination. Here is one of the preserved documents of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, with the appeal of the Zemstvo Chief to the Kursk Governorate Board: “…I have the privilege to provide two travel permits No. 413 and 417, taken away from the peasants of the Novaya Tavolzhanka settlement of the Belgorodsky Uyezd, Fedor Dmitriev Fursa and Anton Alekseev Smyk, as those who failed to use their right for resettlement and returned back to their homeland owing to the lack of funds to move to the place of resettlement. Zemstvo Chief, signature. June 11, 1891” (Ibid. L. 125).

On the basis of the available materials, it is difficult to judge whether the peasants did reach the Tomsk Governorate, according to the nominal list, or not; for this end, it is necessary to analyze the local documents, in the archives of the Tomsk Region.

Resettlement of the Kursk people

Kursk Governorate occupied the first place in the resettlement movement in 1885–1889: those who left it

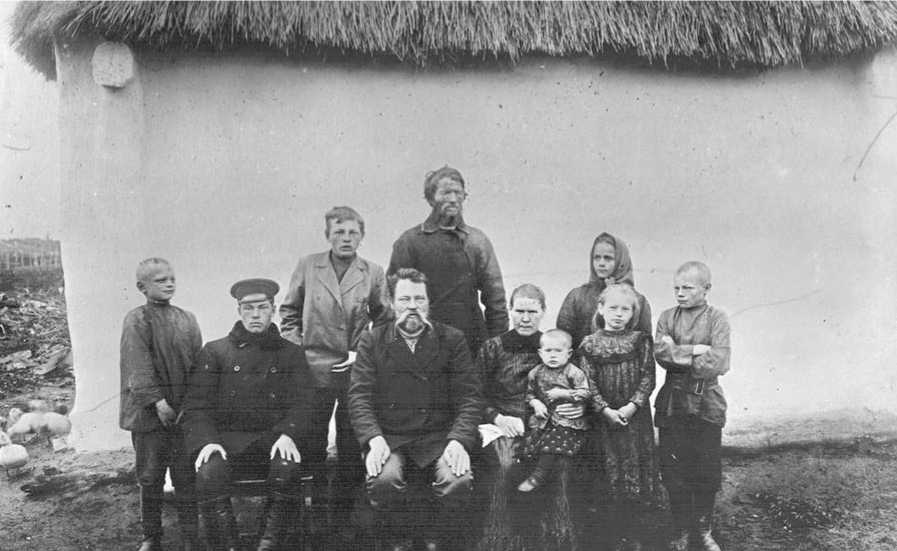

Fig. 2 . South Russian settler (top right) with Siberian peasants. Photo by M.A. Krukovsky . 1912. MAE archives.

accounted for 43 % of the total number of migrants; in 1890–1894, the second place (14 %) after the Poltava Governorate; in 1895–1899, the third place (7 %); and in 1900–1904, it was the fifth (6 %) (Pereseleniye v Sibir…, 1906: 15). According to the data of the Resettlement Administration, in 1896–1914, 279,695 s.o.s. of migrants and walkers left the Kursk Governorate, of which 67,948 people “moved in the opposite direction”, i.e. returned (Itogi pereselencheskogo dvizheniya…, 1916: 2). For the majority of the Kursk peasants, the process of resettlement included two stages: the first was passage to the Tomsk Governorate to the migration point, the second (after two years or more) was settlement in the villages to the south of this area, mainly in the Altai Mountains District (Fig. 2, 3).

The arrival of the Kursk people to the Siberian lands was reflected in a number of names of settlements and entire regions of Western Siberia, for example, Sudzhensky Uyezd of the Tomsk Governorate, the settlement Kursky in the Bagansky District of the Novosibirsk Region, the village of Kursk in the Kulundinsky District of the Altai Territory, etc. Family legends have been preserved about the Kursk people as the founders of new settlements. We have heard many such stories in the villages of Alekseevka, Parfenovo, and others in the Topchikhinsky District of the Altai Territory (Semenova, 2010) (Field Materials of the Author (FMA), 2015). In the “Final Settlement and Volost Cards of the All-Russia Agricultural Census of 1916–1917” preserved in the GATO, various volosts of the Tomsk Governorate show lists of settlers of the Tomsky Uyezd, Sudzhenskaya Volost*, but unfortunately, only general information about the settlers is given, without indicating the places of their exit (GATO. F. 239, Inv. 17, No. 4, 8, etc.). The first field expeditions in the village of Sudzhanka, Yaysky District, Kemerovo Region, did not reveal the descendants of the Kursk migrants; only the name of the street “Kursk Territory” remained after them (FMA, 2016). Possibly, in the past, southern migrants changed their rural place of residence to urban and contracted to work in mines, as evidenced by some personal cards of workers of 1940 kept in the Anzhero-Sudzhensk city archives (City Archives of Anzhero-Sudzhensk, Kemerovo Region (GAAS), F. 69, Inv. 2, Vol. 27, fol. 37, etc.).

Here are some examples of migrations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to A.A. and N.A. Vaganov, Kursk migrants arrived in the early 1880s in Burlinskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd** from Stakanovskaya, Krasnopolyanskaya, Pokrovskaya, Khokhlovskaya, Nikolskaya volosts of the Shchigrovsky Uyezd, Afanasyevo-Pokhonskaya, Uspenskaya volosts of the Timsky Uyezd, and Srede-Opochenskaya Volost of the Starooskolsky Uyezd. The nearby Ordinskaya Volost of the Barnaulsky Uyezd*** accepted Kursk people from Stakanovskaya, Nikolskaya, Verkhdoymenskaya

Fig. 3 . Settlers from the Kursk Governorate. Photo by M.A. Krukovsky . 1911–1913. MAE archives.

volosts of the Shchigrovsky Uyezd; Legostaevskaya Volost of the Barnaulsky Uyezd* was populated by settlers from Kotovskaya and Baranovskaya volosts of the Starooskolsky Uyezd (1882: 19, 68, 103). Peasants from the Kursk Governorate that arrived in 1897–1907 in the village of Karasevo, Gondatievskaya Volost, Tomsky Uyezd**, at the time of the agricultural census accounted for about half of the village population: 45 out of 100 households (h/h) (GATO. F. 239, Inv. 16, D. 117, No. 24) (Fursova, 2003: 100). In 1907–1914, families of settlers from the Kursk, Orel, and Tambov governorates founded the villages of Sovinovsky and Sukhinovsky, Gondatievskaya Volost, Tomsky Uyezd (Ibid.: No. 49, 50***) (Ibid.: 98).

Those migrants who arrived in the village Funtiki, Barnaulsky Uyezd, Barnaul Governorate****, founded a separate settlement of Makaryevsky (Makaryevka). Makaryevsky was dominated by the people from the Kyiv Governorate (23 h/h) and Kursk Governorate (11 h/h); at the beginning of the 20th century, their neighbors were the less numbered people from Perm (4 h/h), Voronezh (3 h/h), and Tambov (3 h/h) governorates, etc. (Ibid.: No. 3). In the Community of Nikolskoye, Alekseevskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd (385 h/h), located not far from Makaryevka, most of the population were settlers from Kursk, and fewer from Orel, Tula, and Chernigov (Ibid.: No. 4).

Modern residents of these settlements retain their founding histories, which, on the one hand, were similar to one another, because they developed as a reflection of social, political, and cultural processes of their time, and on the other hand, they were unique, due to specific situations and circumstances. For example, the Kursk people chose to settle in what was considered an old-resident village: Voznesenskoye, Pokrovskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd. In 1888, approximately 25 families from Oboyansky Uyezd of the Kursk Governorate arrived here. They were allowed to settle in the dacha area of this village. The new settlement was called Malinovy Log (Shvetsov, 1899: 17). The rapidly growing new settlement disturbed the old residents and, after disputes and lawsuit, was annihilated by decision of the administration. One part of the Kursk people moved to the village of Voznesenskoye (where the migrants from the Sudzhanskaya Volost, Kursk Governorate, also arrived), and the rest dispersed to the neighboring villages.

The settlement of Rodina, Pokrovskaya Volost, was founded in 1891 by 15 families of peasants from Graivoronsky Uyezd, Kursk Governorate (Shvetsov, 1899: 51). For the most part, the people of Kursk were dissatisfied with this place, and dispersed for the winter to other villages. Only four Belevtsev families remained in the village. In the summer of 1892, when a large party of Poltava peasants (104 families) arrived in the neighboring village of Yaroslavtsev Log, the Kursk people offered them to unite in the village of Rodina. A year later,

15 more families from Chernigov and 5 families from Kharkov joined them.

Not far from the city of Barnaul, settlers from Kursk and Kharkov founded the villages of Chudskiye Prudy and Abramova Dubrava of the Kasmalinskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd, as indicated by S.P. Shvetsov, on St. Peter’s Day (1899: 64). The village of Utichye, Karasukskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd, was also founded in 1888 by Kursk migrants—by two families from Oboyansky Uyezd. The peasants, with their permissive certificates, were on their way to the Mariinsky District, but taking into account the stories and recommendations of local old residents, they changed their route. They liked the place at Lake Utichye, and the following year more than 20 Kursk families arrived here, and later, settlers from Kursk, Tambov, Poltava, and Kharkov governorates (Ibid.: 75, 76).

Peasants from Kursk were also settling in the already existing villages. For example, the village of Mikhailovsky of the Lyaninskaya Volost, Barnaulsky Uyezd, was founded in 1888 by 30 families from the Poltava Governorate; in the 1890s, 90 families arrived here from the Kursk Governorate (Novoskolsky, Karochansky, and Putivlsky uyezds), 80 families from the Saratov Governorate, 20 more families from Poltava (Pereyaslavsky Uyezd), and five families from Chernigov (Ibid.: 132).

Conclusions

The archival materials in the places from where the settlers derived, are interesting because they reveal the post-reform village atmosphere in southern Russia; the obvious and hidden reasons for resettlement; the structure, social and ethno-cultural composition of a population ready to migrate to Siberia. As follows from the GAKO documents, not all peasants who submitted a petition were granted permission to move; the reasons for the refusal could be a poor financial situation, or, on the contrary, the sufficiency of land plots in their ancestral home.

In many cases, they moved in large family groups, with adults and small, even newborn, children, brothers and sisters, nephews, etc. Judging by the composition of the families, the elderly did not plan to move; according to the documents, the oldest members of the migrant families were 60–65 years old. According to the recollections of the descendants of the migrants, the elderly members of families hardly adapted to life in a new place, and “because of longing” returned to their native places. It is obvious that Siberia was attractive for those representatives of the rural population of the southern outskirts of Russia who were not the most disadvantaged groups. These were the middle-class peasants, whose family groups included several sons. As follows from some documents, one of the reasons for the move could have been the desire of the heads of families to help their sons to avoid military service, which might be considered a hidden motive for migration.

The Kursks people who arrived in Siberia, like other South Russian settlers, were the carriers of not only their regional “Kursk” identity (“Kursk nightingales”), but also of an all-Russian, as well as specific ethno-cultural, local, and class identities (Old Believers, Cossacks, Sayans, etc.), which can probably explain the existence of many popular collective nicknames among the Kursk peasants in their motherland and in Siberia (Zanozina, Larina, 2004: 35). According to the GAKO documents, migrants arrived in Siberia mainly from the southern regions of the Kursk Governorate—Timsky, Starooskolsky, Novooskolsky uyezds, etc. South Russian and Ukrainian peasants who moved to Siberia often changed their surnames, adding the ending “-ov” to them, apparently in the hope of becoming more Russified and thus adapting. Were such actions accompanied by a change of identity? Such a situational identity was inherent in people for whom the (external) change of identity was not difficult; in terms of differential characteristics of their culture, they occupied an intermediate position between Southern Russians and Ukrainians.

In Barnaulsky Uyezd, as well as in other places in the south of Western Siberia, the Kursk peasants began their Siberian history together with other southern Russians, but especially often with Poltavites, Kyivites, etc. Joint co-residence with the Ukrainian population fully corresponded to the previous situation in the historical homeland, the so-called “culture of rootedness” (Chizhikova, 1988: 24). In cases where migrants were settled with old residents, conflict relations often arose; although, in 1916, marriages of old residents and settlers were already common (as a rule, a bride was from an old resident family, and a groom was a migrant). The most striking example of this is the emergence of families from the people of Kursk and Tomsk, or Kiev and Tomsk. Subsequently, this led to the formation of the Siberian (local and regional) variants of the South Russian culture (Fursova, 2016: 550). At the same time, the Kursk migrants, who came in groups of families from the same places and even settlements, were carriers of specific ethno-cultural traditions that did not imply mutual hostility with neighbors of Ukrainian origin. All this in the future became the reason that the “Yuzhaks”, owing to the processes of acculturation, “dissolved” among the Russian old residents and Ukrainian settlers.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, Project No. 22-28-00865.

Список литературы South Russian settlers of Western Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, based on archival documents and field studies

- Bagalei D.I. 1887 Ocherki iz istorii kolonizatsii stepnoy okrainy Moskovskogo gosudarstva. Moscow.

- Chizhikova L.N. 1988 Russko-ukrainskoye pogranichye: Istoriya i sudby traditsionno-bytovoy kultury. Moscow: Nauka.

- Chizhikova L.N. 1998 Etnokulturnaya istoriya yuzhnorusskogo naseleniya. Etnografi cheskoye obozreniye, No. 5: 27-44.

- Fursova E.F. 2003 Etnokulturnoye vzaimodeistviye vostochnoslavyanskikh starozhilov i pereselentsev Priobya, Baraby, Kulundy po materialam kalendarnykh obychayev. In Problemy izucheniya etnicheskoy kultury vostochnykh slavyan Sibiri XVII-ХХ vv. Novosibirsk: AGRO-SIBIR, pp. 80-129.

- Fursova E.F. 2016 Vzaimovliyaniya v svadebnoy obryadnosti u sibiryakov kursk-chernigovskogo proiskhozhdeniya v pervoy treti XX veka. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 550-552.

- Itogi pereselencheskogo dvizheniya za vremya s 1910 po 1914 g. (vklyuchitelno). 1916 N. Turchaninov, A. Domrachev (comp.). St. Peterburg: Izd. Pereselench. upr.

- Krylov M.P. 2009 Regionalnaya identichnost naseleniya Yevropeiskoy Rossii. Vestnik Rossiyskoy akademii nauk, vol. 79 (3): 266-277.

- O dvizhenii naseleniya v Kurskoy gubernii za 1899 god. 1904 Kurskiy sbornik s putevoditelem po gorodu Kursku i planom goroda. Kursk: Izd. Kur. gub. stat. komiteta, pp. 68-79.

- Pereseleniye v Sibir. 1906 Pryamoye i obratnoye dvizheniye pereselentsev semeinykh, odinokikh, na zarabotki i khodokov, iss. XVIII. St. Petersburg: Izd. Pereselench. upr.

- Popov I.I. 1911 Pereseleniye krestyan i zemleustroistvo Sibiri. In Velikaya reforma. Russkoye obshchestvo i krestyanskiy vopros v proshlom i nastoyashchem, vol. IV. Moscow: pp. 249-267.

- Semenova O.N. 2010 Iz istorii osnovaniya stareishikh sel na territorii Topchikhinskogo rayona. In Rodnaya storona. Barnaul: Pyat plus, pp. 17-40.

- Shvetsov S.P. 1899 Materialy po issledovaniyu mest vodvoreniya pereselentsev v Altaiskom okruge. Barnaul: [s.n.]. (Rezultaty statisticheskogo issledovaniya v 1894 g.; No. 11. Iss. II: Opisaniye pereselencheskikh poselkov).

- Vaganov A.A., Vaganov N.A. 1882 Khozyaistvenno-statisticheskoye opisaniye krestyanskikh volostey Altaiskogo okruga. [s.l., s.n.].

- Zanozina L.O., Larina L.I. 2004 Arkhaichniye kollektivniye prozvishcha kurskikh krestyan. In Etnografi ya Tsentralnogo Chernozemya Rossii. Voronezh: Istoki, pp. 35-39.