Substitute offering: an Ob Ugrian ritual tradition surviving in the 20th and early 21st century

Автор: Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145374

IDR: 145145374 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.122-128

Текст обзорной статьи Substitute offering: an Ob Ugrian ritual tradition surviving in the 20th and early 21st century

An offering, to accompany prayer to a deity, is one of the main elements of the religious-ritual practice of the Ob Ugrians. This ritual was strictly regulated by their spatial and temporal prescriptions. Fellowship with the God was achieved through prayers and offerings accompanying the most important events of human life from birth to death. In the case of severe illness or ailment, a person had the right to a temporal delay of the offering: an effigy was substituted for the real animal. Another reason for a substitute offering was the sheer absence of a requisite animal (people were not engaged in animal husbandry, there were no animals because of poverty, reindeer were at distant pastures, etc.).

The substitute-offering ritual practiced by the northern Khanty and Mansi population was observed by A. Kannisto in the Lower Konda, Upper Losva,

Upper Severnaya Sosva in the early 1900s, and by the Novosibirsk researchers in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra (hereinafter—KMAO–Yugra) and the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (hereinafter— YNAO) in 1985–2017.

The Ob-Ugrian tradition of substitute offering as described by Kannisto

The Voguls from the Lower Konda River asked a shaman for prescriptions as to which specific animal should be offered in case of a particular illness. The shaman was supposed to eat a fly agaric and have a nap; having awakened, he went out of his house and informed the guardian spirit what animal would be offered. The shaman mentioned, for example, a horse—“the one with a mane” (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 286). Apparently,

the illness did not make it possible for a sick person to perform the offering ritual; moreover, an ailment was considered an inappropriate state for such a ritual observance (cf. The temporal prohibition for ritual practices upon human’s death).

At Konda, people used to cut a flat figurine of a sacrificial animal from birch-bark: a horse for a supreme god; a cow, sheep or cock for a supreme god or guardian spirits. The sacral effigy could be made by a shaman or a person unrelated to and older than the sick offeror. This member of the ritual held the birch-bark figurine in his hand and moved it around the head of the sick person from east to west three or four times. If the sick person was able to pray, he addressed the supreme god with the following prayer:

Blessed man, blessed father!

In the day of illness, when we got sick,

In the day of suffering, when we got distressed,

We drive

With our hand an ungulate animal as a bloody sacrifice to you, With the live hand – a horned animal.

Would you sweep me, would you wave your hand Holding a goose feather, a duck feather.

With a good support as large as a bosom, a knee

Support me! (Kannisto, Liimola, 1951: 310–311).

After prayer, the birch-bark effigy was put on a windowsill close to the head of the sick person’s bed. When the sick person recovered, the animal offering ceremony was performed and the birch-bark effigy was burnt. If the person died, the real offering was not performed (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 299).

At the Upper Losva River, in case of a person’s illness, substitute offering of horse- or reindeer-effigies cut from birch-bark was performed for a particular guardian spirit. Effigies were mostly offered to major gods: Khul-otyr (in case of smallpox), Polum-torum , or Mir-susne-khum ; offerings to family guardian spirits were less common. During the ritual, people used to say: “A reindeer image should be cut for Yevtim-sos-otyr-pyg , who saved many souls from illnesses” or “I promised to offer you a horse with a mane, do not torment me any longer!” (Ibid.: 298). Birch-bark effigies were used to wrap banknotes, and this bundle was moved around the head of the sick person clockwise, with prayer. After that, the effigy was tied into a corner of the sacrificial head cloth, and put in a sacral chest. After recovery, when the actual animal was sacrificed, the birch-bark figurine was taken from the chest, dipped into the animal’s blood, and torn into pieces. Alternatively, the effigy was burnt (Ibid.: 299).

A similar tradition was recorded by Kannisto among the Voguls inhabiting the upper reaches of the Severnaya Sosva: if a sick person died, an actual animal was not sacrificed, instead the effigy was burnt (Ibid.). Kannisto described in detail the sacrificial goods from several sacral chests. One of the chests contained the goods offered to Tapal-old man (Polum-torum): two summer sable skins, and four head cloths, one of which had a folded birch-bark reindeer effigy (sali khuri ‘reindeer image’) tied into one of the corners. Kannisto wrote that such a representation was cut when vowing to offer an animal, and was discarded when the offer was fulfilled (Ibid.: 314). Another chest, which stood at the rear shelf in the Vogul dwelling, contained many multicolored, black, or white sacrificial cloths; at its bottom lay a bird representation cut from cardboard (Ibid.: 315).

In case of unsuccessful hunt or absence of a requisite domestic animal, a substitute offering was made with an effigy cut from birch-bark for the family or forest guardian spirits (Ibid.: 299).

Substitute offering in the Ob Ugrian tradition of the late 20th to early 21st centuries

The field studies by the present author in northwestern Siberia have yielded new information; a few substitutes have been photographed for the first time in the history of research. Furthermore, it has been discovered that in the 20th century substitute offering was performed in two cases: when a person was ill and was not able to make an actual offering to the deity, and when no requisite domestic animal was available. Both options are addressed below.

Substitute offering in case of illness. Kannisto described the ritual of cutting an animal figurine from birch-bark, moving this figurine around the sick person’s head, and praying, which survived in more recent times. In the late 20th century, for the first time, the situation was described when the sick person was a child: “If a child got sick, one should pray for the gods to take pity. I will promise to offer a reindeer for my child’s recovery, and will put a head cloth into the chest. When you cut a reindeer effigy of birch-bark, it’s like you make a sacrifice. When an actual reindeer is offered, the birch-bark effigy has to be burnt” (the village of Timka-paul, Sovetsky District, KMAO–Yugra; informant A.V. Dunaev, a Mansi; Field Materials of the Author (hereinafter—FMA), 1997). Among the Lyapin Mansi, the information was recorded that around her sick son’s neck, a mother tied arsyn , the sacrificial cloth, which was removed in four days and put into the chest where family guardian spirits were kept (the village of Khurumpaul, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra; informant P.I. Khozumov, a Mansi; FMA, 1985).

The birch-bark effigies represented either a horse or a reindeer. The sacrificial representation of a horse is mostly typical of the Mansi population of the Severnaya Sosva River basin. For instance, in Khalpaul, the cult attributes remaining upon the death of the first husband of M.V. Pelikova were kept in a large barn located near the house. Inside the barn, two suitcases and a birch-bark box were placed on two wide shelves at the rear wall. One of the suitcases contained sacrificial head cloths, bunches of fox skins, two sacrificial blankets, a warrior’s helmet, and a small bundle of red fabric, containing a silver saucer and a horse representation cut from birch-bark. Another birch-bark horse figurine, wrapped in foil, was kept at the bottom of the suitcase (Gemuev, Baulo, 1999: 39–42).

In the same village, in a sacral chest, among home fetishes belonging to G.V. Tasmanov, arsyns , sable-

0 3 cm

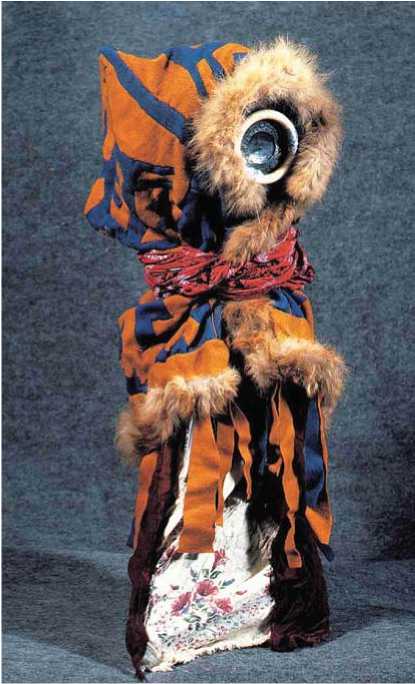

Fig. 1. Figurine of a guardian spirit ( a ), and a birch-bark reindeer effigy placed into its clothes ( b ).

and squirrel-skins, a few shirts, and a birch-bark horse figurine, which was wrapped in white cloth, were kept (Ibid.: 42).

Birch-bark reindeer effigies have been revealed both among Mansi and Khanty people. Several such effigies were found at the bottom of sacral chests: in particular, in the attics of the houses of A.N. Vadichupov, a Mansi (Kimkyasui, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra; FMA, 1997), and of Khanty people: A.A. Alyaba (Vershina Voykara, Shuryshkarsky District, YNAO; FMA, 2001) and the Artanzeevs (Yamgort, Shuryshkarsky District, YNAO; FMA, 2005).

The substitute offering from a sick person was mostly made for the home (family) guardian spirit; therefore, the birch-bark animal effigies were often kept together with this person’s clothes. For instance, in a house of T.I. Nomin, a well-known Mansi shaman, a large anthropomorphic figurine of Nyays-talyakh-oyka-pyg ‘a son of a man from the upper reaches of the Nyays River’ was kept. Its body was made of several red and white cotton head cloths; into the corners of the cloths, coins of 10, 15, and 20 kopeks produced in 1940–1953 were tied. A birch-bark reindeer effigy 8.7 × 5.8 cm was wrapped in one of the cloths (Ibid.: 69) (Fig. 1). The figurine of the guardian spirit of Mansi Khozumov’s family (Yasunt, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra; FMA, 1999) was made of four shirts (pink, red, blue and motley), on which a robe made of thick red woolen cloth and a red shirt were put. Silver coins of 5 kopeks of 1858 and 1859 were placed between the clothes. A reindeer birch-bark effigy was sewn on the edge of the red shirt close to the head of the guardian spirit (Baulo, 2013: Fig. 119). An anthropomorphic figurine cast in lead and dressed in several shirts and robes, dated to the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, represented a guardian spirit of the Khanty family of Shianov (Lokhpodgort, Shuryshkarsky District, YNAO; FMA, 2017). The body of this figurine was girded with a red woolen cord, holding a reindeer birch-bark effigy.

Substitute offering in case of the absence of a requisite domestic animal. Such a situation was rather typical, and was the result either of a person’s poverty, or of his/her temporary absence from home; for instance in summer, when reindeer were driven for pasturing in the Northern Urals.

For the rituals of substitute offering to family guardian spirits, horse- or reindeer effigies were most often cast in lead (more rarely, carved of wood). The figurine, together with a coin or a banknote, was wrapped into a piece of fabric and placed into the sacral chest. Lead horse figurines were found in the family sanctuaries of the Mansi family of Sambindalov (Yany-paul, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra) (Fig. 2), the Khanty Noviyukhovs (Yukhan-gort, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra) (Baulo, 2016: Fig. 7), and also among the

Kunovat Khanty (FMA, 2017). Lead reindeer figurines were found in the Khanty villages of Anzhigort, Karvozh, and Nimvozhgort, Shuryshkarsky District, YNAO (Ibid.: Fig. 256, 257). A wooden reindeer figurine was revealed at the Khanty sanctuary, near the village of Khoryer of the same district (Ibid.: Fig. 73).

When Mansi and Khanty people could afford it, they bought Russian or Zyryan toys (Gondatti, 1888: 7, 16; Glushkov, 1900: 72) representing horses (Fig. 3) or reindeer (made of copper, papier-mâché, rubber, or plastic) as offering substitutes (Baulo, 2016: Fig. 71, 72, 146, b; 149, 263, 264; 2013: Fig. 217). In the village of Khoshlog, a massive cast copper figurine of a horse with a bell on its neck was presented to heavenly gods: the horse figurine, together with a silver saucepan produced in Moscow in 1830 and copper and silver coins of the 1840s–1890s, were wrapped in a silk head cloth (Baulo, 2013: Fig. 219). Here, additional objects increased the value of the temporary substitute. The association of the animal figurine with the silver saucepan could have also been a holdover from an old custom of using only metal dishes to serve and consume the offering’s meat (Chernetsov, 1947: 120).

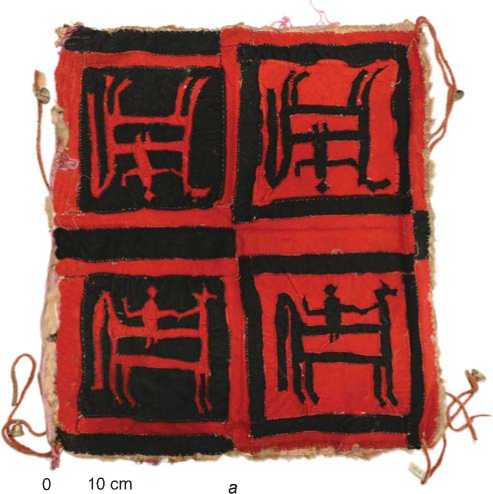

Another example of the substitute offering is a red figure of a horse which is represented on a unique blanket of woolen cloth, 88 × 42 cm, kept by a Mansi K. Pakin (Verkhneye Nildino, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra) (Gemuev, 1990: 117) (Fig. 4).

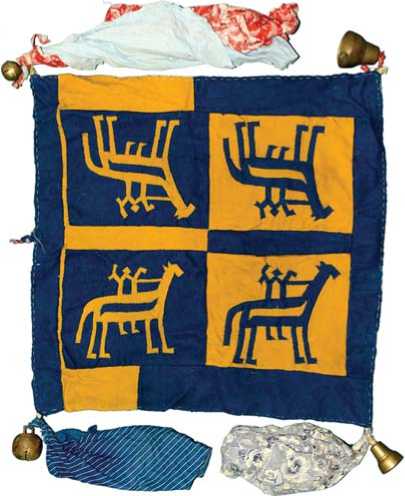

Combined version of the substitute offering. A birchbark or paper effigy could supplement the other cult object, like a sacrificial blanket made for Mir-susne-khum ‘worldwatching man’, and a large head cloth manufactured for Goddess Kaltas . Among the home fetishes belonging to A.N. Vadichupov, a Mansi mentioned above (FMA, 1997), there was a sacrificial blanket, 67 × 71 cm, made of red and black woolen cloth edged with squirrel fur, and bearing the images of four horsemen. It was

Fig. 2. Lead horse effigy, with a silver coin fused into its body.

Fig. 3. Papier-mâché horse effigy—an attribute of the family sanctuary.

manufactured in the early 20th century. The blanket’s face was covered with a pink silk head cloth, sewn to the cloth along the edges. Between the cover and the cloth, a birch-bark effigy of a cock was placed (Fig. 5). Notably, a cock is a rather typical offering of the northern groups of the Ob Ugrians. According to P.A. Infantiev (1910: 14), the cock was “a favorite offering to home shaitans”; similar information was reported by V.N. Chernetsov (Istochniki…, 1987: 166), I.N. Gemuev (1990: 173–174, 192), E.G. Fedorova (1996), and others.

10 cm

Fig. 4. Sacrificial blanket with a horse image.

0 3 cm

b

Fig. 5. Sacrificial blanket ( a ) with additional birchbark cock effigy ( b ).

In the field season of 2016, in Khurumpaul of the Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra, a sacrificial blanket, 60 × 60 cm, was found, made of yellow and blue woolen cloth and edged with squirrel fur, and showing four images of horsemen. Two patches of multicolored cotton fabric, two copper bells, and two rattles (one of copper and one of iron) were attached to each corner of the blanket. One of the narrow patches at one of the corners was tied around a piece of paper, 7.4 × 6.2 cm, folded in two and bearing a reindeer image drawn with a pencil (Fig. 6).

We have noted other articles that had been additionally offered to Goddess Kaltas and not reported as substitute offerings earlier. For example, in 2015, in the village of Yukhan-gort, Berezovsky District, KMAO–Yugra, a large silk reddish-purple head cloth ornamented with golden-yellow floral embroidery was purchased from the Noviyukhov family of Khanty. The head cloth was edged with a strip of black cotton fabric, to which, along the perimeter, gray threads symbolizing a Goddess’s silver with the threads is 160 × 10 hair were sewn. The head cloth is 86 × 86 cm; the size 0 cm. Silver 10-kopek coins from the year 1905, and 20-kopeks of 1923, together with a small “kerchief” 3.0 × 2.6 cm, cut of a small birch-bark piece, were wrapped into one of the head cloth’s corners.

а

b

Fig. 6. Sacrificial blanket ( a ) with additional paper representation of a reindeer ( b ).

а

0 10 cm

b

Fig. 7. Silk head cloth ( a ) and birch-bark “kerchief” ( b ).

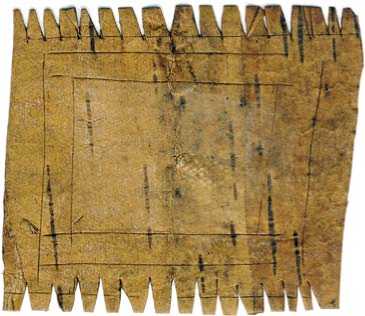

The central square part of the small “kerchief” was marked with lines cut with a knife; its long sides were decorated with scallops imitating the sewn-on threads (Fig. 7).

In 2016, in the village of Lombovozh of the same district, a square head cloth offered to Goddess Kaltas was purchased from a Mansi. It was made of pink fabric, and was embroidered with blue and yellow threads. The head cloth was edged with a broad strip of red fabric, with gray threads attached to the edges. The head cloth is 100 × 90 cm; the size with the threads is 176 × 166 cm. Small copper bells were sewn on to the corners of the article; a copper ring was tied to one of the threads; a silver 10-kopek-coin of 1870 was tied to one of the corners; the other corner wrapped an effigy of a coat or a robe, cut from birch-bark, 4.5 × 4.5 cm in size (Fig. 8). The offering of overclothes (both ready-made and tailored) to guardian spirits was reported by many authors (see, e.g., (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 314–318; Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 33; Gemuev, 1990: 106; Bogordaeva, 2008; 2012; and others)).

Conclusions

Materials collected by A. Kannisto and field-materials of the author’s describe the tradition of substitute offering among the northern groups of the Ob Ugrians throughout the 20th to early 21st centuries. Substitution was practiced in case of the offeror’s illness, the absence of a requisite animal, or an unsuccessful hunt.

In the case of illness, the specific substitute was prescribed by a shaman; the sacral effigy had to be made by someone unrelated to and older than the sick person. Researchers described birch-bark figurines representing

0 3 cm

Fig. 8. Birch-bark figurine representing a coat or a robe.

horses, reindeer, cows, sheep, and cocks. A substitute offering was intended for the family’s guardian spirits; therefore, the birch-bark effigies were usually placed in its clothes. Upon the sick person’s recovery, the actual animal was offered, and the birch-bark figurine had to be burnt or torn into pieces. In reality, these figurines were usually kept among other cult attributes. If the person died, no real offering was performed. In the case of a child’s illness, the substitute offering had certain specific features. In the absence of a requisite domestic animal, a horse- or reindeer-figurine was cast of lead, or readymade toys were used in the ritual.

The combined version of the substitute offering represented the use of a birch-bark (or paper) image in addition to the tailored sacrificial blankets and head cloths.

Thus, the new information on the practice of substitute offering among the northern Ob Ugrians, throughout the 20th to early 21st centuries, adds significantly to our knowledge of the tradition of communication between a human and the realm of deities and guardian spirits.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Program XII.187.1 “Identification, Study, and Preservation of the Cultural Heritage of Siberia in the Information Society”, Project No. 0329-2018-0007 “Study, Preservation and Museumification of the Archaeological and Ethno-Cultural Heritage of Siberia”; state registration No. AAAA-A17-117040510259-9.