Tantra or Yoga. Clinical Studies, Part 2: Tantra

Автор: Oscar R. Gómez

Журнал: Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara @fundacionmenteclara

Рубрика: Artículos

Статья в выпуске: 1, Vol. 10, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Several clinical studies show how exercises in Vedic traditions, such as Yoga, or Theravada or Mahayana Buddhism, as well as tantric practices, have a significant psychobiological impact. This study seeks the neurophysiological correlate of practices called tantric and non-tantric meditations through a qualitative systematic review of the data collected. Tantric practices were shown to increase sympathetic activity, "phasic alertness," and performance in cognitive-visual tasks. They promote greater wakefulness, decreased propensity to sleep, increased cognitive activity, and metabolic changes contrasting with those resulting from non-tantric practices due to the relaxation induced by such practices. Tantric practices create calmness and mental clarity, with enough energy and excitement to function effectively in the environment, managing irritability, stress, fatigue, fear, and anxiety. The spiritual experience of "awakening" and "self-realization" has a neurofunctional and anatomical correlate of neuroplastic modifications that create new levels of sensitivity, perception, and self-perception.

Clinical studies, tantra, Buddhism, Vajrayana, Hindu, meditation, EEG, ECG, fMRI, neuroimaging, neurophysiology, immunology, endocrinology

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211564

IDR: 170211564 | DOI: 10.32351/rca.v10.390

Текст научной статьи Tantra or Yoga. Clinical Studies, Part 2: Tantra

Introduction – Part Two

As mentioned in the first part, unlike the scriptures and meditation instructions of the Vedic tradition, Yoga, Theravada, or Mahayana, which were widely disseminated and aim to achieve stillness and calm , the tantric scriptures—" reserved only for rulers "—aim to increase alertness and warn against excessive calm (Rinpoche, 1999). Tantric practices do not cultivate relaxation but a state of maximum alertness (Corby, 1978). That is, being conscious and awake (Amihai, 2014). For this reason, having opposite objectives, they would also have opposite results.

This highlights the philosophical, social, and cultural consequences of these different types of tantric and non-tantric meditations.

This review compiles the available scientific evidence regarding the possible neurophysiological correlates of tantric practices to confirm, with this evidence, that the objectives of each group are met and to verify if the physiological results reflect this same theoretical opposition.

Through clinical studies, it is shown how tantric practices create better cognitive and physiological responses: increased arousal and "phasic alertness" (Amihai, 2014) while significantly reducing stress levels (Batista, 2014), in contrast to the results obtained from non-tantric meditation types.

This study shows the psychobiological consequences of these two groups of philosophies and practices. Non-tantric philosophies, being exoteric in nature1, were widely disseminated, so most people are familiar with their principles and techniques. This is not the case with tantric philosophy and practices, as they are esoteric and "reserved only for rulers," and few know them as they truly are.

This review has been divided into three topics. In the first part, the neurophysiological correlates of the results of meditative practices derived from Yoga and Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism were reviewed. In this second part, the results of tantric practices are reviewed, and in the third part, they are compared.

To continue the line of research outlined in the first part and extend it to the social and individual consequences of these different practices, we will present esoteric Tantrism, its differences with other philosophies, its objectives, and the techniques developed to achieve them. Then, we will present the corresponding neurophysiological results of tantric constructions and practices.

Methodology

A qualitative systematic review of available studies on the neurophysiological consequences of meditations practised within esoteric Hindu Tantrism and Buddhist Tantrism or Vajrayana. A bibliographic search was conducted using the following keywords: meditation, tantra, tantrism, tantric, Buddhism, esoteric, Tibetan, Vajrayana, Hindu. Each keyword was searched individually and combined using the appropriate Boolean connector with each of the following keywords: EEG, ECG, fMRI, neuroimaging, neurophysiology, immunology, and endocrinology. The search was conducted in both Spanish and English, using the following platforms: MEDLINE (PubMed), ISI Web of Knowledge, TripDatabase, Cochrane Library, and the references of the consulted articles were also exhaustively analysed. The search included articles published before May 2017.

There is a wide variety of techniques referred to as "meditation," with such diverse forms and objectives that it is impossible to create taxonomies that encompass them all. Therefore, we suggest that future research use the term "exercises" for Yoga, Mahayana, Theravada, Vipassana, or tantric practices. For this research, we will refer to tantric meditation techniques as those originating from esoteric Hindu Tantrism and esoteric Buddhist Tantrism or Vajrayana, and non-tantric techniques as the rest of the meditation forms.

Development – Part Two: Tantric Practices

Tantrism began to develop in an India (Lorenzeti, 1992) whose political system established different types of people (Akira, 1993), social castes, perpetuated in power or slavery depending on the caste into which they were born "reincarnated." For each caste, different laws and practices (Zimmer, 1953), rights, and obligations (Samuel, 2008) were established.

Faced with this extreme condition of social inequality, Mahavira— precursor of Jainism (Glasenapp, 1999)—and Buddha, if he existed (Gómez, 2017), first constructed an epistemology, a method for finding the truth—which at the time was considered revealed— 2and both concluded that reality does not exist, that it is a cultural construction, and that the truth is what they individually see with their own eyes (Capra, 2000). Therefore, there is no true reality but a particular vision of reality. Then, with more rigour and political possibilities than Descartes, they systematically destroyed all revealed truths to establish a notion of the subject emancipated from mythological gods and equal at birth, thus without a priori existence (Gómez, 2016).

We want to highlight that the Hindu conception, upheld to this day by those who disseminate the philosophy of Yoga, Theravada, and Mahayana, of reincarnation excludes the possibility of social equality3.

Based on these foundations, the so-called tantric texts were written. In India, under the patronage of the Sailendras, they gave rise to the Kaula school, which lasted until the 13th century in India. For those who attributed the authorship of these texts to Buddha, Buddhism was expelled from India and took refuge in Southeast and Central Asia and Tibet until 1959 (Acri, 2016) (Chhaya, 2009).

These two tantric schools, Kaula and Buddhist, developed a new non-theistic model of thought (Gómez, 2016) and constructed the notion of the subject not divided into body and soul, thus equal at birth. This notion allows anyone to elevate their human condition, as read in the "Pancha Tantra" and the "Kularnava Tantra" (Vishnu, 1949) (Wilson, 1826) (Shiva, 7th century AD) (Gómez, 2017).

From this conception, they proposed liberation for people but from the chains of ignorance and superstitions to which they were subjected by the political system. They proposed awakening individuals one by one. And they proposed for everyone the possibility of modifying their social condition and transforming themselves. Achieving self-realization beyond the deterministic notions of social castes.

In this way, the conceptual differences in the word "liberation" for exoteric Hindu and Buddhist philosophies and for tantric philosophy become clear. Moksha, " spiritual liberation ," for Vedic philosophy, and Mukti, " liberation from a heavy yoke, from a burden, from slavery ," for esoteric tantric texts4 (Gómez, 2017).

The former aimed to liberate the lower castes from suffering by developing karmic explanations so they would understand that their pain and humiliation are a direct consequence of their own actions in past lives, which they must accept with approval to "spiritually evolve" and have a better reincarnation in the next life, along with exercises to achieve relaxation and mental stability under these oppressive conditions.

The latter, tantric philosophy, sought liberation but from slavery. It sought to enlighten—first by educating and then by enlightening—to bring people to the same condition of humanity and dignity, regardless of their birth condition. And it developed techniques to achieve this goal. Meditative techniques—reflective to understand the condition of human equality, cultural conditioning, and how to overcome them—(Yeshe, 1987) and meditations—and here the word "meditations" should urgently be replaced by "exercises"—such as deity meditation, Rig-pa, g-tummo meditation, and opening meditation, which were used in this research for tantric training programmes (Gómez, 1996).

As we have shown, tantric and non-tantric practices have little in common. The common aspect between these two, and their different procedures, is that both aim to modify the behavioural, cognitive, and physiological patterns of practitioners. However, given the significant differences in the procedures used in these exercises and the results obtained from the practices, we point out the widespread error of conducting comparative clinical trials between the two to determine the mechanisms and neurophysiological results of both tantric and non-tantric meditation techniques (Travis, 2010). Therefore, in this second part, the results of clinical research on tantric practices are analysed.

Unfortunately, very few scientific studies have been conducted exclusively on Hindu and Buddhist tantric meditation techniques (Wilson, 1826) (de Mora Vaquerizo, 1988) (Harper, 2002) (Brooks, 1992).

The vast majority have focused on those that proliferated in the West from the New Age, Vedic schools such as Yoga, or exoteric Buddhist or Hindu Tantrism5, since, as we have mentioned, not only is the true philosophy of Tantrism unknown6, but so are its internal practices7. For this reason, we will briefly explain what tantric meditations consist of.

Among the tantric practices, we will first study deity meditation, Rig-pa, and g-tummo, concluding with opening meditation, as described in the "Kularnava Tantra," the "Kalachakra Tantra," and other unclassified texts that until a few years ago were still available in the tantric monastery of Gyuto in exile (Shiva, 7th century AD) (Dalai Lama, 1984).

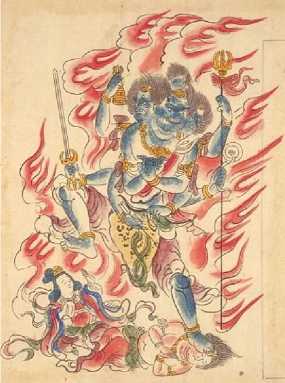

The so-called "self-generation as a deity," emerging as a deity—as described by Yeshe (1987)—and generalised as deity meditation, originated in Hindu and Buddhist tantric traditions in India and was later adopted by Tibetan Buddhism (Snellgrove, 2003). The practice involves maintaining focus on an internally generated image of a deity surrounded by its environment.

The content of deity meditation is rich and multimodal, requiring the generation of colourful three-dimensional images, such as the deity's body, ornaments, and environment, as well as sensorimotor body schema representations—such as in the case of kinkara—(Gómez, 2012) and the deity's feelings and emotions. The image temporarily replaces the sense of self and the internal perception of the real world (Gyatrul, 1996). In Tantra, the visualisation of oneself as a deity is related to the generation or development stage, which is the first stage of meditation practice (Sogyal, 1990).

Trailokyavijaya : One of the meditational deity images. It is the equivalent of the Hindu deity Vidyaraja and represents the Lord of Knowledge. In two of his hands, he carries a vajra and a bell, and at his feet lie the defeated bodies of Shiva and Shakti. © Wikimedia.

Another tantric practice is Rig-pa meditation—concrete knowledge or clear knowledge—which follows the final stages of deity meditation and represents the completion stages of meditative practice (Tulku, 1999). The meditator visualises the dissolution of the deity and their entourage into emptiness and aspires to achieve awareness devoid of dualistic conceptualisations of a discursive nature (Yeshe, 1987) (Dalai Lama, 1994) or pre-conceptions, a priori judgments.

While practising Rig-pa, the practitioner tries to distribute their attention evenly so that it is not directed toward any object or experience. Although various aspects of experience may arise, such as thoughts, feelings, images, or sensations, the meditator must let them flow without stopping to examine or dwell on them (Wangyal, 1993) (Goleman, 1996). Rig-pa is considered a meditative practice without a meditation object; it does not require noting or observing the content of attention or the activity associated with the dual mind but simply being fully aware of it (Tulku, 1999).

Another tantric practice included in this research is the so-called "inner heat." The g-tummo meditation practice, aimed at controlling "internal energy," is described by Tibetan practitioners as one of the most secret spiritual practices in the Indo-Tibetan traditions of Vajrayana Buddhism and Bon (Dalai Lama, 1994). It is also called the "inner heat" practice (Yeshe, 1997) because it is associated with descriptions of intense sensations of body heat along the spine (Gómez, 2008).

The g-tummo practice is characterised by a special breathing technique accompanied by isometric muscle contractions, where, after inhalation, during a very brief period of breath retention (apnoea), practitioners contract their abdominal and pelvic muscles (Evans-Wentz, 2002). While performing three quick, deep inhalations, attention is focused on visualising an ascending flame that begins below the navel, in the pelvis, and rises to the crown of the head with each inhalation. Then, calming the breath, the practitioner visualises and cultivates the sensation that the entire body is filled with bliss and warmth (Yeshe, 1987).

Pioneering and significant studies on these tantric practices include those by Benson between 1971 and 1990 and those conducted by the Argentine Association of Psychobiological Research between 1993 and 2001, following the research line of Reich (1945) and Benson himself. We will not consider Reich's conclusions because, after conducting his clinical trials, he attributed the physiological consequences of Tibetan Buddhist tantric practices to the production of what he called " love energy " or " orgone energy " (Reich, 1955), as the measurement instruments of the time did not allow sufficient amplification to validate it as a measurable electrical current in nanovolts8.

One of these studies clearly demonstrated that the meditative practices of the Vajrayana traditions—Tibetan Buddhist Tantra—and Hindu Tantra induce a state of arousal rather than relaxation (Benson, 1990).

In contrast to relaxation, arousal is a physiological and psychological state of being "awake" and reactive to stimuli (Kozhevnikov, 2009). It is characterised by increased activity of the sympathetic system, followed by the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the endocrine system (Camm, 1996), resulting in the state of "phasic alertness" (Petersen, 2012) (Sturm, 1999). That is, a significant temporary boost in the ability to respond effectively to stimuli (Weinbach, 2011).

Moreover, while tonic alertness can occur simultaneously with relaxation, the state of "phasic alertness" results from increased activity of the sympathetic system and is therefore inconsistent with the state of relaxation.

Tantric meditations thus produce an increase in "phasic alertness" and, specifically, deity meditation generates an immediate and substantial improvement in performance on cognitive-visual tasks, consistent with the state of arousal and sympathetic activation (Brefczynski-Lewis, 2007).

One study, which included control subjects, states: "Practitioners of deity meditation demonstrated a dramatic increase in performance on imagery tasks compared to the control group. The results suggest that deity meditation significantly enhances the practitioner's ability to access visuospatial processing resources" (Kozhevnikov, 2009).

Other studies show in the collected results that Vajrayana practices, specifically g-tummo, in addition to increasing sympathetic system activity and generating an arousal response (Benson, 1982), also produce an increase in body temperature (Kozhevnikov, 2013), which also indicates a sympathetic response.

By attaching a small thermometer to the armpits of highly experienced g-tummo meditators with 6-32 years of experience, Kozhevnikov et al. (2013) were able to demonstrate for the first time that g-tummo meditators increase not only their peripheral temperature but, more importantly, their core body temperature during meditation, showing that the activity of the sympathetic nervous system increases significantly as a result of this practice.

In particular, the thermogenesis induced during g-tummo was so significant that it raised the meditators' body temperature above the normal range and into the range of mild or moderate fever—up to 38.3 °C—reflecting an increased arousal response due to sympathetic activation. The generation of body heat without external heat— thermogenesis—is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system (Morrison, 2011).

In humans, thermogenesis is primarily caused by brown adipose tissue, which diverts energy obtained from the oxidation of free fatty acids into heat, which is then distributed throughout the body via the vasculature of the adipose tissue.

It is important to note that the activity of brown adipose tissue in humans is stimulated by the sympathetic nervous system, and this is what leads, from the brown adipose9 tissue, to g-tummo-induced thermogenesis.

The study by Kozhevnikov (2013) on the tantric meditation called g-tummo and how it allows for an increase in body temperature was conducted in monasteries in eastern Tibet with expert meditators while they performed g-tummo practices, measuring armpit temperature and electroencephalographic (EEG) activity.

It has long been recognised that an increase in body temperature, at the threshold of a mild fever as produced during g-tummo, is associated with a heightened state of alertness, faster reaction times, and improved cognitive performance in tasks such as visual attention and working memory (Wright, 2002).

So far, it has been verified that the psychophysiological result of the tantric meditations called g-tummo, deity meditation, and Rig-pa consists of an increased capacity for "phasic alertness," enhanced cognitive activity, and metabolic changes contrary to the results of relaxation and in line with the philosophical postulates of Tantrism. It could be inferred that this increase in arousal would, in turn, elevate stress symptoms.

However, a study conducted at the Stress Studies Laboratory of the Department of Structural and Functional Biology at the University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, and the Metabolic Unit of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at the University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, shows that, in the short term, a tantra yoga programme10 led to a decrease in cortisol production, and in the long term, it induced higher cortisol production in the morning and lower production in the evening.

These effects contributed to the physical and mental well-being of the participants (Batista, 2014).

The objective of the study was to evaluate the acute and chronic effects of tantra yoga practice.

A quantitative study using a pre-post-test group design was conducted. Twenty-two volunteers (7 men and 15 women) participated, taking a tantra yoga programme for six weeks, with 50-minute sessions twice a week, always at the same time in the morning.

Data were collected in the first week and at the end of the sixth week of the programme. Salivary cortisol concentration (SCC) was used to measure the physiology of distress and analyse the short- and long-term effects of tantric meditations. Psychological distress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ)11. The results (mean ± standard deviation) were analysed using the Wilcoxon test (p < 0.05).

The research yielded the following results: SCC decreased by 24% after the first week (0.66 ± 0.20 μg/dL vs. 0.50 ± 0.13 μg/dL) and the last week (1.01 ± 0.37 vs. 0.76 ± 0.31 μg/dL), showing the short-term stressreducing effect of tantric yoga practice.

The long-term effects were analysed by the daily rhythm of cortisol production. Initially, volunteers showed altered SCC during the day, with nighttime values (0.42 ± 0.28) higher than midday values (0.30 ± 0.06). After the programme, SCC was higher in the morning (1.01 ± 0.37) and decreased during the day, with the lowest values before sleep (0.30 ± 0.13). Training in tantric meditations was also effective in reducing PSQ scores (0.45 ± 0.13 vs. 0.39 ± 0.07). Specifically, the management of irritability, tension, and fatigue in the PSQ decreased (0.60 ± 0.20 vs. 0.46 ± 0.13), as did the management of fear and anxiety (0.54 ± 0.30 vs. 0.30 ± 0.20).

As evidenced by this research, tantric techniques result in a greater capacity for alertness and responsiveness but from a state of calm and mental clarity.

The final form of tantric meditation we will investigate is the so-called "openness meditation." This form of meditation does not directly focus on a specific object but cultivates a state of being. In this same vein are deity meditation and g-tummo. Openness meditation is practised in such a way that the intentional aspect, the object-oriented focus of the experience, seems to dissipate in the meditation.

By training their emotional and behavioural mechanisms to detach from the apparent object of their initial intention, by training toward a goal they know a priori they will not achieve or that lacks importance, practitioners train their system to enjoy the action itself, independent of the result. This training aims to enable people who "live for the desire for pleasure" to "live for the pleasure of desire" (Gómez, 2008).

This dissipation of focus on a particular object is achieved by allowing the very essence of the meditation being practised—such as compassion—to become the sole content of the experience, without focusing on specific objects.

Using techniques similar to deity meditation, during the practice, the practitioner lets their feeling of kindness and compassion or the emotional or attitudinal essence of a role model permeate their mind without directing their attention toward a particular object (Dalai Lama, 1994).

A significant study on this form of tantric meditation was conducted by Lutz (2004) and involved eight advanced Buddhist tantric practitioners, with an average age of 49 ± 15 years, and 10 healthy volunteer students with an average age of 21 ± 1.5 years. The Buddhist practitioners underwent mental training in the same Tibetan traditions of Nyingmapa12 and Kagyupa13 for 10,000 to 50,000 hours over periods ranging from 15 to 40 years.

The control subjects had no prior meditative experience but had expressed interest in meditation. The controls underwent meditative training for one week before data collection.

An initial baseline electroencephalogram (EEG) was collected, consisting of four blocks of 60 seconds of continuous activity with a balanced random order of eyes open or closed for each block. Then, the subjects generated three meditative states, only one of which is included in this research.

During each meditation session, a 30-second block of resting activity and a 60-second block of meditation were collected four times sequentially.

The subjects were verbally instructed to begin meditation and meditate for at least 20 seconds before the start of the meditation block.

The study focused on the final objectless meditative practice, "openness meditation," during which both controls and Buddhist practitioners generated a state of "unconditional love, kindness, and compassion."

The meditative instruction was: " Generate internally the state of unconditional love and compassion ," described as an " unrestricted willingness and availability to help living beings ."

This practice does not require concentration on specific objects, symbols, or mandalas—images—; practitioners focus on people or groups of people (Gómez, 1996).

Because benevolence and compassion permeate the mind as a way of being, this state is called "pure compassion" or "non-referential compassion" (Lutz, 2004).

One week before data collection, meditative instructions were given to the control subjects, who were asked to practise daily for one hour. The quality of their training was verbally assessed before the EEG recording.

During the training session, control subjects were asked to think of someone they cared about, such as their parents or loved ones, and let their mind be filled with a feeling of love or compassion, "imagining a sad situation and wishing to be free from suffering and seeking well-being for those involved." After some training, the subjects were asked to generate such feelings toward all sentient beings without thinking specifically of anyone in particular.

During the EEG data recording period, both controls and experienced practitioners tried to generate this non-referential state of kindness and compassion. During neutral states, all subjects were asked to be in a non-meditative and relaxed state.

This research showed a significant increase in gamma frequency range activity (<25-70 Hz)14 during the generation of the meditative state of compassion.

The high-amplitude gamma activity found in some of these tantric practitioners is the highest reported in the scientific literature in a non-pathological context (Baldeweg, 1998).

The gradual increase in gamma activity during meditation aligns with the view that neural synchronisation, as a network phenomenon, requires time to develop, proportional to the size of the synchronised neural assembly. However, this increase could also reflect an increase in the temporal precision of thalamocortical and corticocortical interactions rather than a change in the size of the assemblies (Singer, 1999).

This gradual increase also corroborates the verbal reports of the Buddhist subjects regarding the timing of their practice. Typically, the transition from a neutral state to this meditative state is not immediate and requires 5-15 seconds, depending on the subject. The endogenous gamma-band synchrony found here could reflect a change in the quality of moment-to-moment awareness, as claimed by Buddhist practitioners and postulated by many models of consciousness (Tononi, 1998) (Engel, 1999).

Posner found a difference in the normative EEG spectral profile between the two groups during the resting state before meditation. It is not unexpected that such differences are detected during a resting baseline, as the goal of meditation practice is to transform the initial state and diminish the distinction between formal meditation practice and daily life. This study is also consistent with the idea that attention and affective processes, which may reflect gamma-band EEG synchronisation, are flexible skills that can be trained (Posner, 1997).

Summary of Results of Tantric Meditations

Our research yielded the following results for the forms of meditation encompassed under the term "tantric":

-

1. Produce an increase in sympathetic system activity, followed by the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the endocrine system.

-

2. Induce a state of arousal rather than relaxation.

-

3. Generate an increase in "phasic alertness" and, specifically, deity meditation produces an immediate and substantial improvement in performance on cognitive-visual tasks.

-

4. Create a state of relaxed alertness, protecting the system against the extremes of hyperactivity—excitement, restlessness, anxiety—and hypotonia—laxity, drowsiness, sleep.

-

5. Promote greater wakefulness and reduced propensity for sleep, especially as the practice advances.

-

6. Generate increased cognitive activity and metabolic changes, contrary to the relaxation produced by non-tantric practices.

-

7. Produce an increase in peripheral and core body temperature.

-

8. Substantially reduce stress in the short term, and this reduction is sustained without the need to continue the practice. In the long term, the system of a subject undergoing brief training induces higher cortisol production in the morning and lower production in the evening.

-

9. Have effects, verified through the PSQ, that contribute to the physical and mental well-being of subjects who underwent a 12-week training programme.

-

10. Produce neural synchrony, particularly in the gamma frequency range (25-70 Hz), involved in mental processes such as attention, working memory-learning, and conscious perception. It was found that:

-

11. Rig-pa meditation allows the practitioner to develop awareness of their own consciousness, building an early warning system against impulsive negative actions.

-

12. Deity meditation significantly enhances the practitioner's ability to access all visuospatial processing resources and improves cognitive and affective competencies. It develops a new level of sensitivity,

The high-amplitude gamma activity observed in some of these tantric practitioners is the highest reported in the scientific literature in a non-pathological context.

perception, and self-perception, as well as an increase in compassion for other beings. This is verified after a one-week training programme.

Conclusion of Part Two

As evidenced by this study, tantric techniques result in a greater capacity for alertness and responsiveness but from a state of calm, mental clarity, and sufficient energy and excitement to function effectively in the environment, managing irritability, stress, fatigue, fear, and anxiety.

Among the results observed, the most significant are the state of arousal and "phasic alertness"—produced by deity meditation and g-tummo—and the mental calm induced by Rig-pa practice.

The construction of arousal is complex and multidimensional, with multiple distinct but overlapping inputs, including cortical, autonomic, endocrine, cognitive, and affective systems (Derryberry, 1988).

While other studies have focused more on somatic forms of arousal, such as Holmes (1984), we focus on the cognitive dimensions of arousal, which refer to wakefulness and alertness.

Thus, tantric practice engenders greater and prolonged wakefulness, which may be an indicator of neuroplastic changes produced by tantric practices (Britton, 2014).

In this sense, "awakening" is not a metaphor but rather an interactive process of neuroplastic modifications and increased efficiency that develops a new level of sensitivity, perception, and self-perception (Britton, 2014). We also conclude that, in tantric practices, "selfrealization" is not a metaphor either. It is the possibility for a trained individual to become what they desire to be, to actualize themselves.

Additionally, Rig-pa meditation allows the practitioner to develop awareness of their own consciousness, building an early warning system before the practitioner performs an impulsive negative action (Becerra, 2011).

Recent studies report that raising body temperature through g-tummo practice could be an effective way to boost immunity and treat infectious diseases and immunodeficiencies (Singh, 2006), as well as induce synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Masino, 2000).

Therefore, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the increase in body temperature during g-tummo practice could lead to the development of effective self-regulatory techniques in "ordinary" individuals—for example, non-meditators—to regulate their neurocognitive functions and combat infectious diseases. We suggest clinical studies focused on this tantric practice, g-tummo, with expert subjects and control subjects, to develop simple and effective clinical application techniques.

Regarding the tantric meditation called "openness meditation," which has as its psychobiological correlate an increase in gamma-band frequencies, we found that several clinical studies show the general role of neural synchrony, particularly in gamma frequencies (25-70 Hz), in mental processes such as attention, working memory-learning, and conscious perception (Fries, 2001) (Rodríguez, 1999).

It is believed that such synchronizations of oscillatory neural discharges play a crucial role in the constitution of transient networks that integrate distributed neural processes into highly ordered cognitive and affective functions (Singer, 1999) and may induce synaptic changes (Paulsen, 2000).

Neural synchrony emerges here as a promising mechanism for studying the brain processes involved in this tantric meditation.

Furthermore, Gusnard and Raichle (2001) have highlighted the importance of characteristic patterns of brain activity during the resting state and argue that such patterns affect the nature of changes induced by an activity. The differences in baseline activity reported here suggest that the brain's resting state can be altered by long-term meditative practice and imply that such alterations may affect meditation-related changes.

Therefore, more research, particularly longitudinal research, following individuals over time in response to tantric training, should be conducted.

Based on the results obtained, we propose the following:

-

1. Conduct further studies on techniques involving trained subjects and control subjects to rapidly disseminate findings within the scientific community, as we agree with Zeidan's (2014) idea that "if the benefits of the technique can be produced after a brief training period, then patients may be more inclined to practise, and clinicians may be less reluctant" to recommend tantric practices to their patients.

-

2. Conduct longitudinal clinical research to establish the long-term effects of these practices, both the desired effects demonstrated in this study and potential adverse side effects.

-

3. Create postgraduate training programmes in this discipline and incorporate them into formal clinical practices.

-

4. Incorporate tantric training into formal education, especially at initial levels—as effective programmes for personal growth, emotional management, and attentional control—which can then be replicated in society, as evidenced by neurophysiology and EEG and fMRI recordings,

which show that tantric practices increase non-distracted attention, cognitive competencies, and levels of compassion for others.

Regarding this last point, we want to emphasize that sufficiently validated studies, starting with Posner (1997), demonstrate, without error, that attention, conscious control of attention, and affective processes are flexible skills that can be trained.