The Andronovo age women's costume, based on finds from Maytan, Central Kazakhstan

Автор: Tkachev A.A., Tkacheva N.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145365

IDR: 145145365 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.035-042

Текст обзорной статьи The Andronovo age women's costume, based on finds from Maytan, Central Kazakhstan

Clothing is an important and highly specific component of any traditional culture. The costume and its elements indicate the sex, age, and social status of an individual, as well as his or her role in the life of the community. Although the Bronze Age burial sites have been studied for a long time, the problem of reconstruction of the Andronovo clothes and their semiotic functions is far from resolved. The issues of reconstruction of Andronovo women’s costume are addressed in various publications, including several summary works (Kupriyanova, 2008; Usmanova, Logvin, 1998; Usmanova, 2010). Yet, the data on men’s and women’s costumes are quite insufficient, fragmentary, and discrepant. Comprehensive analysis of all available materials on the Andronovo and other similar cultures of the Bronze Age in the steppe zone of Eurasia has shown that unlike women’s clothes, men’s day-today and funeral costume had almost no decoration. For that reason, particular features of men’s clothing can be reconstructed only tentatively, on the basis of ethnological data (Kuzmina, 1994: 159–162).

New approaches to the study of human clothes and to their reconstruction are based on the materials from the Maytan cemetery, which provides information on various aspects of human life in the steppes of central Kazakhstan during the Bronze Age. Maytan is the only completely excavated Andronovo burial site. During the thirty years following the completion of excavations, several publications have been released: analysis of the burial rite (Tkachev, 2013a), social

Women’s personal decorations and their spatial distribution in graves represent a special interest, and make it possible to reconstruct particular elements of women’s clothing. Using the archaeological materials from Maytan and other Kazakhstan cemeteries, E.R. Usmanova (2010) and A.A. Tkachev (2014b, 2015) attempted to reconstruct women’s clothes and their details. The presently available data suggest the specificity of the men’s and women’s grave goods kits, yet the available knowledge and conceptions of ancient clothing make it possible to reconstruct only the most typical elements of women’s costume.

Possibilities of women’s costume reconstruction

Men’s burials at the Maytan cemetery contain mostly sets of tools relating to particular occupations, with an almost complete absence of costume decorations; while women’s burials reveal only such everyday goods as small knife and awls (Tkachev, 2013b). Despite the fact that the majority of women’s burials were looted, many pieces of jewelry have been found, which were used for decoration of clothes and parts of the body deserving special marking. These are head; neck and chest; and hands and feet. Since the majority of the burials were disturbed, the found objects can be correlated to a particular decoration category only on the basis of their typology.

The comparative analysis of the recovered grave goods has shown that personal decorations indicate mainly the age group of the buried women. Two age groups can be distinguished: girls and adult women. Below we describe the cases when particular details of women’s costume can be reliably reconstructed on the basis of spatial distribution of personal decorations over the body of deceased.

Girls. A considerable number of excavated graves have been correlated with children given their sizes (90 graves, 42 %). Taking into account communal graves containing remains of representatives of various age groups, children were recorded in 102 burials (47.7 %). Sex determination of the children by their bones is impossible; sex is usually identified via the accompanying grave goods. Yet, it is mostly impossible to correlate all the buried Maytan children with either males or females, because the major part of children’s graves yield only one or two vessels. Furthermore, nearly one third part of the children’s burials (29 graves, 32.2 %) contain ceramic ware or some other goods, while the bone remains are missing.

In burials with bone remains, no regularity in location of goods was established. Grave goods were recorded in 22 children’s burials (24.4 %), including children of all age groups from infants to juveniles (14–15 years old). Judging by the features of burial rite and grave goods, eight children’s burials can be conventionally attributed to males. Others revealed various pieces of jewelry: bangles with rounded disconnected ends, finger rings, plaques, clips, leaf-shaped pendants, amulets of teeth and shells, and bronze and paste beads. All these items belonged to the typical set of Andronovo women’s decorations. A considerable proportion of these burials were disturbed by looters. The original location of ornaments on the bodies and costumes of girls of a younger age group can be established only in four burials.

The simplest headdress, either a cap or a headband decorated with paste beads at the temples, was found on the head of a buried girl 2–3 years old (encl. 22A, grave 1). A similar headdress with a spiral-shaped pendant on the forehead was noted in the infant burial without bone remains (encl. 30A, grave 2). The closest parallel to this headgear was found in a grave in the cemetery at Satan, where the cap was decorated with a plaque on the forehead of the buried infant (Usmanova, 2010: 25, fig. 22).

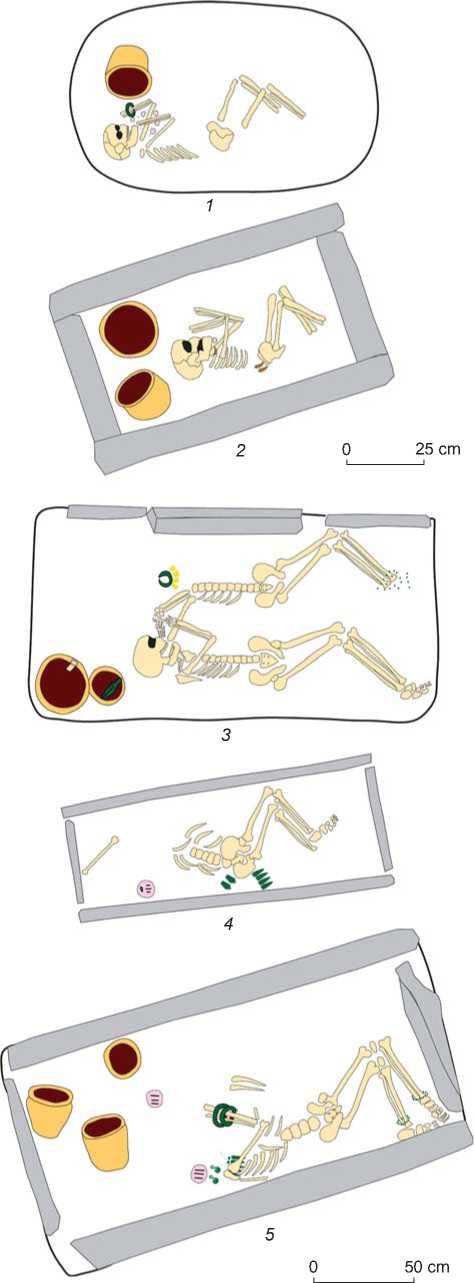

The burial of a girl 3–4 years old (encl. 41B, grave 3; Fig. 1, 1 ) revealed five shells (Fig. 2, 12 , 13 , 16 , 19 , 20 ) and four paste beads in the neck area. These likely represented decorations sewn on the collar of the shirt (dress?) of the deceased (Fig. 3). A fluted bronze bangle (see Fig. 2, 21 ) was noted on the left wrist. This type of bangle is typical of the children’s age group at Maytan. Similar bangles were found on a juvenile of 10–14 years of age (encl. 36A, grave 1) and an infant younger than 1 year (encl. 49, grave 3). Fragments of similar bangles were found in two destructed burials: one of these contained the remains of an old woman and a 6 month-old infant (encl. 50B, grave 2), the other a 3–4-year-old child (encl. 36D). The grave with missing child remains contained bangles, which location (taking into account the position of the body, typical of this site and epoch—flexed position on the left side) suggests that these were put on the wrists (encl. 30A, grave 2).

A burial of a girl 2–3 years old (encl. 15C; see Fig. 1, 2) revealed noteworthy ornaments. Her neck was decorated with a necklace made of a fossilized shell (see Fig. 2, 23), framed by two pendants of a dog’s or a wolf’s molars (see Fig. 2, 26, 27), with a sequence of alternating paste beads (three on each side) and two-part tubular beads (two on each side) at the ends. Two pendants of corsac’s or fox’s canine teeth were found in the waist area (see Fig. 2, 24, 25); these were likely plated into the girl’s hair (Fig. 4). Such a decoration kit was possibly typical of the girls of a younger age group: the remains of a necklace consisting of several paste beads and two pendants of corsac’s teeth were found in one more disturbed infant burial (encl. 32B). Similar decoration sets, marking a young age, have also been reported from other sites in central Kazakhstan. For instance, at the Nurtai cemetery, a grave of a child 7–14 years old yielded fluted bangles and a similar plait decoration (Tkachev, 2002: Pt. 1, p. 184, fig. 56, 8).

Thus, the grave goods of the juvenile female group vary across the studied graves. The majority of child’s graves contained only ceramicware. An insignificant number of burials yielded personal decorations typical of this age group that were used in the daily routine, and also in the burial rite in some special cases, the identification of which is hardly possible. The exception is double burials, where the social status of children, for some unknown reason, was correlated with that of adults.

Adult women. At the Maytan cemetery, several groups of women’s burials have been identified: individual, double burials of individuals of opposite sexes, and, as an exception, burials of adults with children. The majority of women’s burials were disturbed; therefore, despite a considerable number of decorations, it is hardly possible to establish their original location in graves, and neither, consequently, the characteristic features of the women’s costume. Of the total 78 women’s burials, only a few provide sufficient information for reconstruction of the costume details. These are mostly decorations of head, hands, and feet.

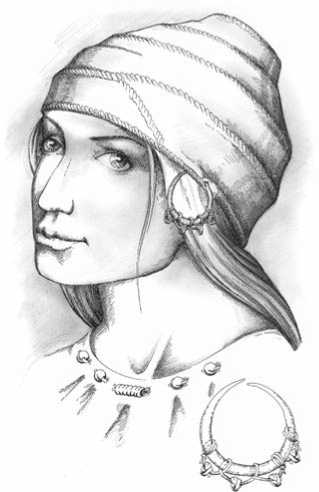

Caps represented one of the major elements of the everyday and burial women’s costume. Three burials provide sufficient grounds for a credible reconstruction of the caps. Notably, owing to the features of soil and of the burial rite, textile remains didn’t survive even in the undisturbed graves. The first grave from this set (encl. 17C, grave 1) yielded the remains of a cap, which, according to the reconstruction, was sewn with paste beads along the lower edge, and was additionally decorated with spiral bronze pendants of one and a half turns coated with gold leaf, in the ear areas (two pendants at each side). The cap was fixed on the head with strings, sewn with paste beads on their upper parts. Another example (encl. 23E, grave 1) was a headgear decorated with gold-coated pendants of one and a half turns, suspended at the right and left sides, 5 pieces at each side. A thread of paste beads and tubular beads served as a decoration of strings and as a suspension framing the face. In the third burial, a cap was decorated with tubular bronze rings at the temples, each bearing four gold-coated spiral pendants of one a half turns (Fig. 5)*. This piece of decoration was found at the head of the buried woman, whose bones were partially missing

Fig. 1. Plans of burials.

1 – encl. 41B, grave 3; 2 – encl. 15C; 3 – encl. 43, grave 1;

4 – encl. 16B, grave 2; 5 – encl. 5B.

йццуро оеац^

лдаао си^

1–11 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18

–

–

1 , 2 , 24–27 , 50

encl. 5B, grave; 12 , 13 , 16 , 19–21

5 cm

Fig. 2. Grave goods

encl. 15C, grave; 29 , 31–33 , 36 , 41–43

–

–

–

encl. 41B, grave 3; 22 , 28 , 30 , 34 , 35

encl. 16B, grave 2; 37–40 , 44–53

–

–

encl. 40, grave 2; 23–27

bone; 3–9 , 11 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 28–35 , 37–43 , 46 , 47 , 51–53

encl. 43, grave 1

–

–

shell; 44 , 45 , 48 , 49 – bronze, gold.

bronze; 10 , 12–14 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 36

Fig. 3. Reconstructed decoration of the shirt’s collar. Encl. 41B, grave 3.

Fig. 4. Reconstruction of a necklace and a plait decoration. Encl. 15C, grave.

(encl. 43, grave 1, a double burial of an adult man and a young woman; see Fig. 1, 3 ). In the ankle area, not less than 150 heavily corroded bronze beads of thin ribbed wire were found, with two threads of beads remaining on each ankle. Additionally, in the grave filling, separate pieces of women’s costume decorations were found (see Fig. 2, 38–40 , 47 , 52 ).

Three bronze pendants of one and a half turns were found in the grave of a woman 20–25 years old (encl. 40, grave 2) at the base of the skull (see Fig. 2, 22 , 28 , 30 ). The observed asymmetry suggests that the pendants were either attached to the left side of the cap, or directly decorated the auricle. This way of using the pendants of one and a half turns was identified for the first time in Altai, at the Andronovo cemetery of Firsovo XIV, where a mummified ear was decorated with similar pendants (Pozdnyakova, 2000: 47–48, fig. 1, 8 ). Later, the locations of similar ornaments in various sites in the Altai and Kazakhstan were interpreted accordingly. This concerns the sites of Rublevo VIII (Kiryushin et al., 2006: 36), Kytmanovo (Umansky, Kiryushin, Grushin, 2007: 30–31), Kenzhekol I (Usmanova, Merts V.K., Merts I.V., 2007: 44–47, photo 1). It can be assumed that the Andronovo people widely used such pendants for ear decoration; yet prior to the discovery of Firsovo XIV, this type of decoration was interpreted mostly as an element of headgear.

Fluted bronze bangles, decorating the wrists of the buried, represented the most typical pieces of a women’s jewelry set (see Fig. 2, 17 , 18 , 21 , 34 , 35 , 51 ). Bronze bangles decorated with either flattened or cone-shaped spirals have been found in 21 burials at Maytan. The number of bangles on a buried individual varies across the sample: a woman from the double burial of individuals of opposite sexes wore one bangle on her left wrist (encl. 36A, grave 2); three other burials revealed bodies with one bangle on each wrist (encl. 17C, grave 1; encl. 40, grave 2; encl. 41B, grave 2); still other three skeletons demonstrated two bangles on each wrist (encl. 5B, grave; encl. 18C, grave 1; encl. 23E, grave 1). One of the graves yielded a leather band 5 cm wide, which was worn under the bangle to prevent staining on the skin (encl. 5B, grave). Similar bangle bands, decorated with paste beads sewn along their edges, have been reported from Balykty (Tkachev, 2002: Pt. 2, p. 9). Another interpretation was proposed by E.V. Kupriyanova (2008: 95–96): she argued that some of these bangles were worn over the sleeves, serving as cuffs.

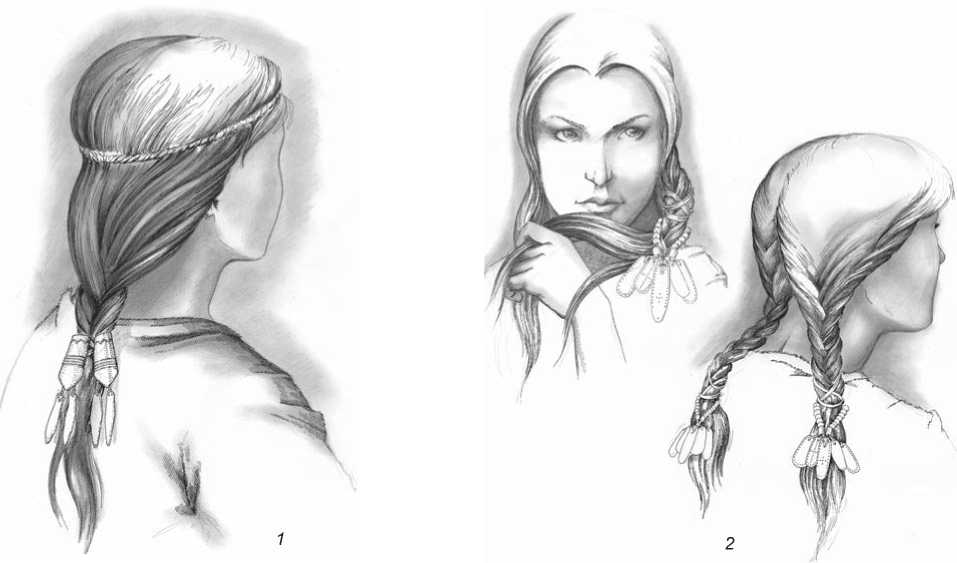

The other typical detail of women’s jewelry set were decorations of the hair. The pieces found in situ make it possible to reconstruct three plait decorations located on the back of the buried. Notably, the archaeological materials from Maytan did not contain any complex plait decorations that were typical of the sites of the Sintashta, Petrovka, and Nurtai cultures.

Fig. 5. Reconstruction of a cap, possible way of attaching temple rings and dress collar decoration. Encl. 43, grave 1.

One of the plait decorations, the decomposed parts of which (see Fig. 2, 31–33 , 41–43 ) were found between the pelvis of the adult woman and the grave’s wall (encl. 16B, grave 2; see Fig. 1, 4 ), represents an intermediate variety between the early (Novy Kumak culture) and late (Alakul-Atasu culture) examples: the specimen does not have any bronze clips characteristic of the early plait pendants. The main element of the plait decoration is ornamented tubular beads, to which four leaf-shaped pendants were attached (Fig. 6, 1 ). The second plait decoration from the headgear of a woman 18–20 years old (encl. 5B, grave; see Fig. 1, 5 ) shows a set of five small ornamented leaf-shaped pendants (see Fig. 2, 3–7 ) combined by bronze clips (see Fig. 2, 8 , 9 ) and plaited into the hair with two narrow leather strings with paste beads. This complex decoration was found at the left shoulder-joint, suggesting a hairstyle consisting of one or two plaits reaching the shoulder blades (Fig. 6, 2 ). The jewelry set also included two strings of bronze beads decorating the ankles, two composite fluted bangles with spiral-shaped ends (see Fig. 2, 17 , 18 ), and two bronze pendants, possibly earrings (see Fig. 2, 11 , 15 ). In addition, pendants made of canine-teeth (see Fig. 2, 1 , 2 ) and shells (see Fig. 2, 10 , 14 ) were found. Judging by the artifacts from disturbed graves, similar plait decorations might have been in the jewelry sets of three other women’s graves.

The third plait decoration is the simplest, containing only three leaf-shaped pendants, found in the loin area (encl. 40, grave 6). This number of pendants is the most typical of the plait decorations, because the simple

Fig. 6. Reconstruction of complex plait decorations.

1 – encl. 16B, grave 2; 2 – encl. 5B, grave.

Fig. 7. Generalized model of women’s costume.

plait is braided of three locks of hair. The same number of leaf-shaped plait-pendants were also found even in several looted graves. Plait decorations are usually found in combination with other head-ornaments; and these were developed towards simplicity. Hence, the later type of plait decorations gradually became the most widespread among all women’s age groups over the Alakul-Atasu area.

Although the majority of graves were looted, the disturbed graves yielded a considerable number of objects, both mass-produced and of individual manufacture. These objects might have been used as decorations of women’s clothing, personal decorations of parts of the body, or as amulets. We can determine the location of a particular item on a women’s costume only hypothetically. However, in some cases the context of the find provides certain information about particular objects. For instance, the archaeological context in one grave suggests that the grave goods included a small leather bag, containing tubular earrings; another case shows the remains of a small rectangular box in the waist area, containing pendants made of animal incisors. The third case reveals a rounded pendant associated with several animal teeth; this concentration likely represents a necklace, which could have been worn by a woman as an amulet. A similar pattern of artifacts’ location within a grave has also been noted in other burials in central Kazakhstan (Tkachev, 2002: Pt. 1, p. 164, fig. 52; p. 177, fig. 62).

It is hardly possible to correlate decoration pieces with particular elements of costume at the chest, waist, or laps areas, because in the surviving burials, there are no decorations in the respective places. The disturbed graves contained isolated strings of beads, which do not provide any ground for reliable reconstruction of costume features.

The Maytan graves, as many other Andronovo sites, revealed numerous bronze beads concentrated around the ankles. Decoration of ankles with strings of beads has been noted in 22 burials, including children’s, individual women’s, double burials of opposite sexes, and men’s and women’s burials with children (Tkachev, 2014b).

Conclusions

The study of the Maytan cemetery did not provide information either about the technology of clothing manufacturing or types of the used materials. However, the data from other Andronovo sites make it possible to hypothesize that the materials were felt, fur, leather, and woolen fabrics, which were sewn of threads made of wool, sinews, or gut (Salnikov, 1951: 138). The styles of women’s wear usually can be reconstructed by the location of beads decorating the collar, cuffs, and lap (Shilov, Bogatenkova, 2003: 260). The Maytan women likely wore long dresses with wrist-long sleeves. The collars in dresses of girls of various ages and unmarried women could be wide; the married women wore dresses having narrow collars with vertical cuts tied up with either leather or textile strings. A dress was likely tied with a belt. Shoes were made either of felt or leather, with the low shafts of leather boots decorated with bronze beads; in the absence of boot-shafts, strings of beads were worn on the ankles as dangle bracelets (Fig. 7). According to the available data, the Maytan women did not wear pants.

Costume was supplemented with various pieces of decoration. On the head, depending on the season, a woolen cap or a headband were worn; these were decorated with beads and tubular rings, which could also be used as earrings, sometimes decorated with spiral pendants of one and a half turns. A typical set included one or two fluted spring bangles with spiral-shaped ends. The bangle could be used as clamps for the dress’ sleeves, or worn over the leather bands on the wrists. Finger rings were decorated with S-shaped signets. A typical hairstyle was either shoulder-length or waist-length plaits interwoven with various decorations.

On the basis of the analysis of the Maytan grave goods kit, we proposed a generalized model of women’s funeral costume. The clothes were mainly uniform, given their utilitarian function and the common ancestry and ideology of the Andronovo tribes, yet there might have been certain specific features in separate regions. The tribes practicing various cultural traditions rendered their ideas of beauty through identical things; but they did not only conform to aesthetic requirements. Clothes-and goods-kit marked the age and sex of an individual, social status, and possibly the particular stages of individual’s socialization.