The bear cult and kurgans of the Scythian elite

Автор: Gulyaev V.I.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145450

IDR: 145145450 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.3.085-093

Текст статьи The bear cult and kurgans of the Scythian elite

Introduction: Research history

Scythian culture and art (in the “animal style”) have always been at the center of Russian scholarly attention. Notably, as early as December 1972, the All-Union Conference on Scythian-Sarmatian Archaeology was organized in Moscow, devoted exclusively to a single but very important topic—the Scytho-Siberian animal style. Leading Soviet experts in Scytho-Sarmatian art exchanged their often differing views on this vast and complex topic. The conference resulted in the publication of a very important book, “The Scytho-Siberian Animal Style in the Art of the Peoples of Eurasia” (Skifo-sibirskiy zverinyi stil…, 1976). This topic has not lost any of its relevance, even today. In addition to numerous articles, several monographs on the specific aspects of Scytho-Siberian art have been published (Perevodchikova, 1994; Korolkova, 2006; Cheremisin, 2008; and others). Nevertheless, this extremely extensive and multifaceted problem is still far from being fully understood.

One of the images occurring in the Scytho-Siberian art is the topic of this study. This is the bear motif in the steppe and forest-steppe Scythia, very rarely mentioned in the studies on the Scythian animal style. Since the 1950s–1980s, a deep conviction has been formed among the Soviet specialists of Scythian studies that this motif had practically nothing to do with Scythia. Quite rare representations of a bear, which were found in some Scythian burials (mostly in the Dnieper-Don forest-steppe region) were either simply ignored or unconditionally attributed to the influence of the Ananyino culture of the Kama region and other cultures of the Urals and Siberia.

What were these views based on? It seems three important circumstances played a role here: first, the universal conviction (of the people of the 20th century) that bears, strong and dangerous predators, lived and still live until this day mainly in taiga, in the remote forest areas, which are prevalent in the northern Urals and Siberia; second, the distribution of the bear cult (or

“Bear Festival”), which is well known from the works of ethnographers among the indigenous peoples of the northern forest territories of Russia; and third, almost complete (until recently) lack of any information on any “ursine” theme in the archaeology of the steppe and forest-steppe Scythia.

We should start with the habitation area of bears in the past—in both ancient and medieval times—as well as in present. This is brief information from an encyclopedia: “Once the brown bear was common throughout Europe, including England and Ireland; in the south its habitation area reached Northwestern Africa (the Atlas Mountains), and in the east it reached Japan through Siberia and China. Brown bears had probably reached Northern America about 40,000 years ago from Asia through the Bering Strait, and over time widely inhabited the western part of the continent, from Alaska to the north of Mexico. At present, brown bears have been exterminated in most of their previous areas of habitation” (Ivanov, Toporov, 1982: 128–129).

However, we are primarily interested in the steppe and forest-steppe areas of the northern Black Sea region. Could brown bears inhabit, for example, the Black Sea coastal steppe? It is known, judging by the current paleogeographical studies, that in the Early Iron Age, forest vegetation reached the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov coasts along the valleys of large rivers like the Don, Dnieper, Southern Bug, Dnestr, as well as small rivers, even in the purely steppe zone of the northern Black Sea region. It is enough to recall the deep forests of Hylaia in the mouth of the Dnieper-Borysthenes, described by Herodotus. What is there to say about extensive broadleaved forests of the Dnieper-Don forest-steppe, where until recently giant oaks with trunks of over one meter in diameter used to grow!*. Naturally, all sorts of animals were abundant there (wild boars, deer, fallow deer, etc.), including bears. For example, bears were seen in the immediate vicinity of Voronezh as late as the late 18th century (Rossiya…, 1902: 76).

1972: 256). Judging by the available data, bears once lived not only in Eastern, but also in Central and Southern Europe. For instance, an advanced bear cult existed in antiquity at the southernmost tip of the European continent—in Greece, where bears were closely associated with goddess Artemis. Every year, splendid feasts were celebrated in her honor, where this animal was offered as a sacrifice. A tame bear was constantly kept in the temple of Artemis. On especially solemn occasions, priestesses of this goddess dressed in clothes made of bear skins. The name Artemis itself is derived from the Ancient Greek word “bear” (Sokolova, 2000: 129). There is still a cult of the bear among the Ossetians who live in the Caucasus Mountains and are the direct descendants of the Scythians (Chibirev, 2008: 167).

Thus, at least in ages past, the “bears–north–taiga” association needs to be seriously adjusted. Formerly, this formidable predator inhabited the whole of Eurasia, which was reflected in the folklore and religious beliefs of many tribes and peoples of the past (Ivanov, Toporov, 1982). Therefore, it is difficult to imagine that the people who lived in Eastern Europe (the northern Black Sea region) in the first millennium BC and who often (willingly or unwillingly) encountered this largest and most dangerous predator in Europe, would not reflect the image of bear in their beliefs, rituals, and art.

The quantity of facts associated with our theme has also significantly expanded today: new archaeological finds have been made relating to the bear cult in Scythian kurgans on the Middle and Lower Don River, as well as steppe and forest-steppe regions of the Dnieper River. In order to successfully address this issue within Scythia, it is necessary to establish major types in the bear motif of Scytho-Siberian art, to identify a chronological framework of their existence, and to calculate the number of corresponding items for each area of their distribution.

The bear motif in the Scythian antiquities

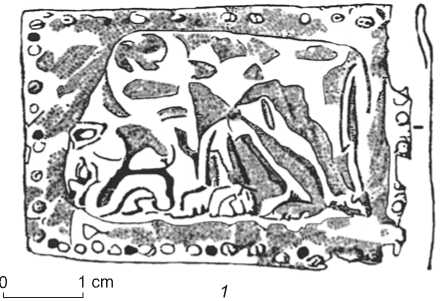

In the Scythian burial complexes, the earliest image of the bear in its full form was first found in the Kelermes kurgan 4 of the second half of the 7th century BC (Fig. 1). This is a silver gilded mirror of the Greek-Eastern (Ionian) production, in which a figure of a walking bear clearly stands out among representations of various gods, people, and animals. The central part of the composition shows the winged goddess Cybele with panthers in her hands, whose functions strongly resembled the Scythian Argimpas—the goddess of fertility of the animal and human worlds. According to specialists, in this case the Greek artisan was guided by the requests of a Scythian customer (Alekseev, 2012: 108). However, this is the Northern Caucasus, the archaic stage of the Scythian culture, and the product of foreign, not Scythian jewelers. Later, the main center of Scythia shifted to the northern Black Sea region.

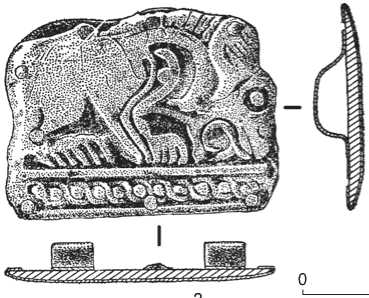

In the Scythian steppe, the bear motif was recorded in the kurgan of Chabantsova Mogila of the 5th century BC, near the town of Ordzhonikidze, in Dnepropetrovsk Region of the Ukraine. In the central tomb (almost completely looted), animal bones (remains of sacrificial food), fragments of iron lamellar armor, a bone handle of a knife, a bronze arrowhead, and a golden casing of a wooden bowl have been found. The representation of a bear standing upright, in profile, with its head down, was made with the stamp on one of the plates of the casing (Fig. 2, 1 ).

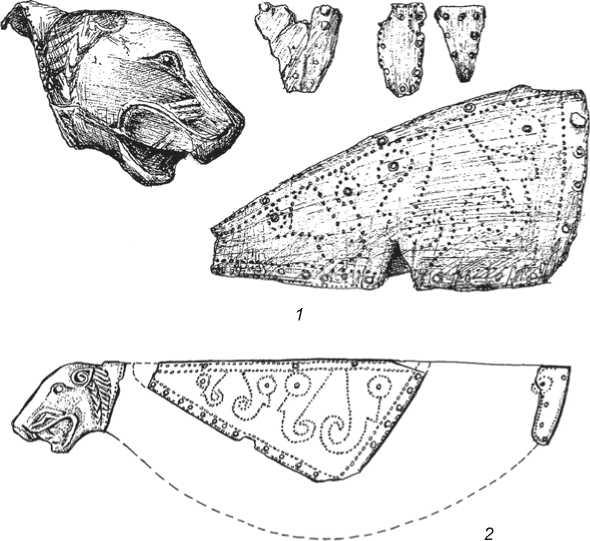

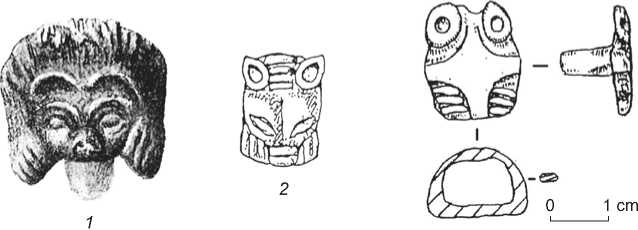

A bear head is represented four times en face (Fig. 3) on a wild boar tusk from the Kiev Historical Museum (an incidental find from the forest-steppe Dnieper River region, the village of Malye Budki, Sumy Region, the Ukraine). E.V. Yakovenko, who described this item, believed that the bear was represented in the “sacrificial position” and, following the tradition, associated the item with the influence of the Ananyino culture (1969: 201).

In the lateral tomb of the Solokha kurgan (near the village of Velikaya Znamenka, Kamensko-Dneprovsky District, Zaporozhye Region, the Ukraine), with the intact burial of the Scythian “king” (390–380 BC), a gold casing of a wooden vessel with a handle in the form of the bear head was found (Fig. 4). When describing this item, A.Y. Alekseev mentioned that “handles in the form of an animal’s heads or figures are relatively rare finds in the kurgans of European Scythia of the 5th–4th centuries BC, but these have also

Fig. 2. Golden casing of a wooden vessel with a bear figure from the kurgan of Chabantsova Mogila, 5th century BC (after (Mozolevsky, 1980: 83)) ( 1 ), and bronze plaque with an image of predator (bear?), covered with silver foil, from the kurgan of Zheltokamenka, 4th century BC ( 2 ).

Fig. 1. Cast silver mirror covered with electrum plates. Kelermes kurgan 4, second half of the 7th century BC. 1 – reverse side of the mirror with representations; 2 – detail of the mirror with a figure of the walking bear.

1 cm

Fig. 3. Tusk of a wild boar with representations of four bear’s heads in the “sacrificial position” (en face). Random find, Sumy Region, the Ukraine, 5th century BC (after (Scythian Gold…, 1999)).

Fig. 4. Gold casing of a wooden vessel, and its handle in the form of a bear’s head. Solokha kurgan, lateral tomb, early 4th century BC (after (The Golden Deer…, 2000)).

1 – drawing of the items; 2 – vessel reconstruction.

been found outside this region. It is possible that such vessels are of eastern origin for Scythia” (2012: 146– 147). One could object to this well-known scholar’s suggestion by pointing out that gold plates of cult wooden vessels with handles in the form of figures of animals and birds have been found (albeit not so often) in the burials of the Scythian elite (their rarity could have largely resulted from the total looting of Scythian graves in the ancient times) (Mantsevich, 1966: 23–25). However, a gold casing from the Chabantsovaya Mogila shows a representation of the standing bear profile. Complete parallels to this image are present on gold fittings of handles of wooden vessels from the Aleksandropol “royal” kurgan (Lugovaya Mogila) in the Dnepropetrovsk Region, and from kurgan 1 of the Chastye Kurgany group near the city of Voronezh (Fig. 5).

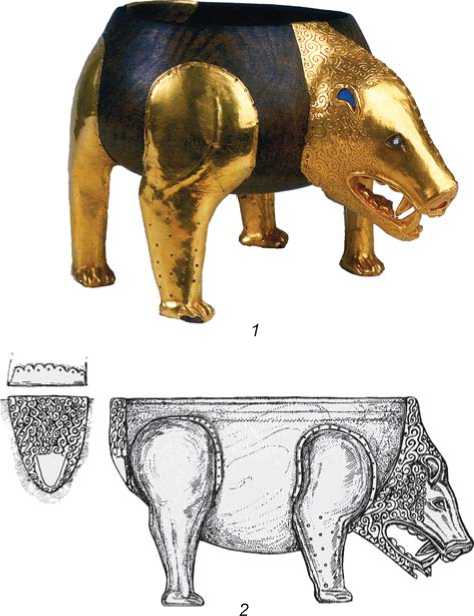

A similar vessel to the Solokha vessel in the form of a bear figure has been found in the Filippovka “royal” kurgan 1 in the Orenburg Region (Fig. 6), belonging to the Sauromatian-Sarmatian culture of the Iranianspeaking nomads from the southern Urals. Four bronze plaques with a silver cover representing the figure of the bear (?) have been found in the “royal” kurgan of Zheltokamenka of the 4th century BC in the steppe Scythia (Mozolevsky, 1982: 221).

Generally, cult wooden vessels with gold casings, on which the images of animals, birds, or fantastic animals (griffins) were stamped, are not rare finds in the kurgans of steppe Scythia of the 5th–4th centuries BC, despite their total looting. Another thing is the image of bear, which is still found quite rarely at the local archaeological sites.

Fig. 5. Gold fittings from the handles of wooden vessels with ursine representations. 1 – Aleksandropol kurgan, 4th century BC; 2 – Chastye Kurgany, kurgan 1, 4th century BC; 3 – reconstruction of a vessel from kurgan 1 of Chastye Kurgany (after (Zamyatnin, 1946: 15)).

Fig. 6. Wooden vessel with gold fittings in the form of a bear. Filippovka cemetery, kurgan 1, early 4th century BC (after (The Golden Deer…, 2000)).

1 – reconstruction of the vessel using composite materials; 2 – graphic reconstruction.

The assumption concerning the existence of some form of bear cult not only in the forest-steppe, but also in the Scythian steppe, has recently received additional confirmation, after the publication of evidence from the elite kurgan of Bliznets-2 (near Dnepropetrovsk), dated to the late 5th century BC (Romashko, Skory, 2009: 68–69). The kurgan was thoroughly looted both in the ancient times and in the 19th century. In the burial of a noble Scythian steppe dweller, five claws of a brown bear were found (the length of the largest was 6.2 cm; that of the smallest 3.6 cm). These were recovered from the filling of an interior grave pit, next to each other. The authors indicated that such finds were very rare in the graves of the Scythian period, and were made only in few forest-steppe sites: tomb No. 2 of the Repyakhovataya Mogila kurgan, near the village of Matusov, in the Tyasmin River basin (six bear claws with drilled round holes, which used to function as bridle adornments); kurgan 2 at the Lyubotin cemetery, in the Seversky Donets River basin (a bear claw cased in gold foil, with a hole for hanging, i.e. an amulet) of the late 7th to early 6th century BC; and the central grave of the Bolshoy Ryzhanovsky kurgan of the early

3rd century BC*, in the interfluve of the Gniloy and Gorkiy Tikich Rivers (four claws located on three sides of the skeleton of a noble Scythian warrior). “In the cases described above, bear claws, like the teeth of a bear and a wolf, should probably be interpreted in the same way as canine teeth and boar tusks, which are quite common in kurgans of the Scythian time, for example, in the Dnieper right bank forest-steppe area of the Kiev region, but are less frequently found in the steppe zone of the northern Black Sea region, which are correctly and unambiguously identified as apotropaic amulets with magical powers. Obviously, the claws of such a mighty beast as a bear were to serve as apotropaia—a reliable defense for the deceased from evil forces. In our case, we have a different, extremely interesting and unusual situation for Scythian burials. Since all five claws of the bear lay… in the same place, close, or rather, together (and this is after the robbery of the burial!), we may consider them as the remains of a bear paw [my italics – V.G. ].

This find makes it possible to recall a group of bronze adornments of a horse bridle—plaques in the form of a “bear paw”, which became widespread in the 5th century BC. Like a number of other items in animal style, which decorated the bridle, these had sacred and magical function. It is tempting to suggest that bear paws might have been used in the Scythian environment as apotropaic amulets, and served as a prototype for creating metal amulets-phylacteries…” (Ibid.).

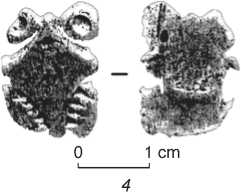

Indeed, bronze plaques of horse bridle in the form of human hand (as some scholars believe), or bear paw (according to other scholars) have been found in the kurgans of the 5th–4th centuries BC of the forest-steppe and (less often) in the Scythian steppe. It is not difficult to explain the ambiguity of interpretation: there are five fingers both on the human hand and on bear paw. Moreover, the rather crude casting of such items does not contribute to a clear distinction. It is true that in very rare cases (at high magnification), one may even see nails, which means that it was clearly a human hand. However, most often the “hand” looks exactly like bear paw; in most cases, it is the right hand/paw. There are dozens of such finds in the forest-steppe of Scythia (Mogilov, 2008: 47, 232). Interestingly, most often, the ends of the fingers are pointed and rather resemble the claws of the bear. The interpretation of such plaques as the images of a bear paw was mentioned by A.A. Bobrinsky (1905: 7) and S.V. Makhortykh (2006: 57–59).

The representation of a bear in the “sacrificial position” (head full-face lying on its front paws) stands out among the “bear” motifs in the Scytho-Siberian art. Such placement of a bear’s head and paws on a wooden deck, or on a special platform, and festive ceremonies around it, was one of the culminating points of the Bear Festival, which had survived among many Finno-Ugric peoples of the Urals and Siberia almost until the late 19th to early 20th century (Alekseenko, 1960).

For a long time, it was believed that the motif of the bear in the “sacrificial position” was purely Finno-Ugric, since such representations, mostly in the form of bronze plaques, often occurred at the end of the Ananyino and especially in the Pyany Bor periods (see, e.g., Glyadenovo bone bed in the Kama region (Spitsyn, 1901)). Two such bronze plaques were accidentally found at the Ananyino cemetery of the 6th–4th centuries BC (Vasiliev, 2004: 281, fig. 6).

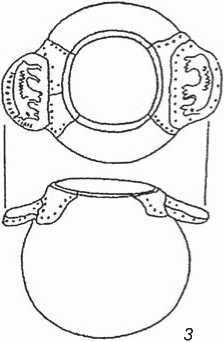

However, it is remarkable that the motif of the bear in the “sacrificial position” also occurs in Scythia: on a golden plaque from kurgan 402 of the 5th century BC near the village of Zhurovka in Chigirinsky Uyezd of the Kiev Governorate, on the right bank areas of the Dnieper forest-steppe (Fig. 7, 2 ); on two bronze plaques of the horse bridle from kurgan 11 also of the 5th century BC near the village of Olefirshchina in Poltava region, in the interfluve of the Vorskla and Psla Rivers (Kulatova, Lugovaya, Suprunenko, 1993: 23, fig. 9, 7 , 8 ); and on two bronze plaques incidentally found in Crimea (one at the village of Batalnoye on the Kerch Peninsula, the other in the southeastern Crimea), both dated to the late 5th century BC (Fig. 7, 4 , 5 ). The fact that the “bear motif” on the Crimean peninsula is far from being accidental is also evidenced by great number of bronze adornments of horse bridle in the form of “bear paws” (Skory, Zimovets, 2014: 125–127), which abundantly occur in the Scythian burial complexes of the Dnieper forest-steppe.

It is also curious that the Scythian kurgans on the Middle Don River do not contain a single plaque with a representation of a bear in the “sacrificial position”, and there are practically no bronze “bear paws”. However, precisely this area of Scythia had the closest trade and cultural ties with the Kama and Ural regions. Though, such finds have been made (and they were not unique) in the Dnieper forest-steppe and Crimea.

Fig. 7. Gold and bronze plaques with a representation of bear’s head in the “sacrificial position” (en face).

1 – Oguz kurgan, 4th century BC; 2 – kurgan 402 in Chigirinsky Uyezd (excavations by A.A. Bobrinsky); 3 – random find from the Ananyino cemetery in the Kama region; 4 – random find from the southeastern part of Crimea, 5th century BC; 5 – random find from the vicinity of the village of Batalnoye, Crimea, 5th century BC.

5 0 1 cm

The question is how cultural influences from the Finno-Ugric world could have penetrated into Scythia, especially in terms of chronology. Bronze plaques with the image of a bear’s head in the “sacrificial position” in the Kama region were first represented by a random find (Ananyino cemetery), dated widely within the 6th–4th centuries BC (Fig. 7, 3 ). Such plaques flourished in the late 4th to 2nd century BC and later. Scythian finds of this kind were confidently dated to the 5th century BC.

What conclusions can be made on the basis of the above facts? First, ursine representations on toreutics and bear claws-amulets for a horse harness appeared among the Scythians at the dawn of their history, in the archaic period. This has been confirmed by the already mentioned finds: a silver gilded mirror from Kelermes kurgan 4 of the second half of the 7th century BC; and six bear claws with holes for hanging to horse bridle from tomb 2 in Repyakhovataya Mogila of the late 7th century BC. It is known that the Scythians came to the northern Black Sea region “from the depths of Asia”, where their ancestral homeland was. Discussions about its location still go on, although such eminent scholars as M.I. Rostovtsev, A.I. Terenozhkin, and A.Y. Alekseev with high degree of confidence placed the ancestral home of the Scythians in Central Asia, that is, in the territory of Tuva, Northern Kazakhstan, and the Altai (Rostovtzeff, 1929: 26; Terenozhkin, 1971: 19–22; Alekseev, 2003: 38–42). Vast forests and magnificent wooded mountains characterize this area—the habitat of many animals (including brown bears). Therefore, even in the earliest times, before moving to the west (to the northern Black Sea region and the Caucasus), the ancestors of Scythians could have used bear image in art and in some forms of its worship.

Notably, traces of bear worship in Scythia have been found in the burial complexes of the highest Scythian elite and even in the “royal” kurgans of the late 5th to 4th centuries BC: Solokha (lateral tomb)—early 4th century BC; Aleksandropol (Lugovaya Mogila)—third quarter of the 4th century BC; Zheltokamenka—340–320 BC (see Fig. 2, 2 ); Oguz (a huge kurgan with a lateral tomb)—third quarter of the 4th century BC (see Fig. 7, 1 ), and Bolshoy Ryzhanovsky—last two decades of the 4th century BC. The burial of a noble young man in the Bliznets-2 kurgan on the outskirts of Dnepropetrovsk, may belong to the same group. Here it is necessary to give some additional explanations.

Ukrainian archaeologists V.A. Romashko and S.A. Skory studied the Bliznets-2 kurgan in May–June 2007. At the start of archaeological work, the kurgan was 7.05 m above the surface. The top of the mound was cut off in the 19th century by a huge looters’ trench by not less than 1 m. Therefore, the initial height of the kurgan was probably over 8 m. Its diameter, recorded by the stone crepidoma, was 42–43 m (Romashko, Skory, 2009: 93). Thus, Bliznets-2 is one of the largest Scythian elite kurgans of the 5th century BC in the northern Black Sea steppe and the largest in the northern part of the region above the Dnieper Rapids. V.A. Romashko and S.A. Skory noted: “Given these parameters, the Bliznets-2 kurgan should be attributed to the third group of kurgans of the Scythian elite, according to B.N. Mozolevsky (1979: 152, tab. 4), which had the height of 8–11 m and in social terms could have been the burial places of members of the royal family or kings who governed the constituent parts of Scythia…” (Ibid.).

The high social status of the person buried in the Bliznets-2 kurgan is also manifested by the size of the grave (catacomb), showing the labor costs for its construction: its depth was 7.5 m, the area of the burial chamber was 34 m2, and the area of the entrance pit was about 7.3 m2. The total area of the burial structure was 41.6 m2 (Ibid.: 94). The tomb of the person was accompanied by three burials of horses (yet, with very

Fig. 8. Scenes of the “royal” mounted bear hunt (after (Frakiyskoye zoloto…, 2013)).

1 – silver gilded dish, Bulgaria, 4th century BC; 2 – silver gilded plaque, Bulgaria, 4th century BC.

inexpensive iron bits and psalia). The deceased lay in a wooden sarcophagus, decorated with carved ivory plates with very fine engraving, depicting various scenes from the life and myths of the Greeks, such as the Dionysian symbols, cheetahs, chariots, dancing Maenads, Eros, Hermes, etc. Romashko and Skory thus wrote: “All the above makes it possible to consider the kurgan as a burial place of the person of the royal rank [my italics – V.G. ], made in the late 5th century BC. We think that this opinion is confirmed by the engraved representation of a shooting archer, wearing barbarian clothes, on the gold ring, in which one may see the scene of the ‘royal’ shooting reflected in the mythology of many peoples of antiquity and having ritual and magical meaning…” (Ibid.: 98). Moreover, the authors believe that in the Bliznets-2 kurgan Orik was buried. Orik was the younger son of the Scythian king Ariapif, who (unlike his brothers Skil and Octmasad) had never been the king of all Scythia, but ruled only one of its parts (Ibid.: 109–112).

Conclusions

It seems that finding some tangible traces of worshipping the bear in the most elite—and in some cases even “royal”—kurgans of Scythia is hardly accidental. Among the Scythian elite, this image occurs most frequently on two types of items: ritual wooden bowls with gold casings, and as an apotropaic adornment on horse harness. In this regard, it should be mentioned that in the neighboring Thrace, with which the highest circles of the Scythian elite had close family (dynastic marriages) and cultural ties, in order to achieve supreme power, one had to take a serious test: to defeat a dangerous beast (a bear, wolf, or wild boar) with a spear and while riding a horse. The scenes of the bear hunt of a mounted Thracian protagonist are represented on the toreutics of the 4th century BC (Fig. 8). In Scythian iconography, a similar subject has been especially vividly represented on silver gilded, two-handed cups from the “royal” kurgan of Solokha, depicting mounted Scythians hunting lions and fantastic monsters.