The cemetery at fort Umrevinsky, in the Upper Ob basin

Автор: Gorokhov S.V., Borodovsky A.P.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145358

IDR: 145145358 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.123-130

Текст статьи The cemetery at fort Umrevinsky, in the Upper Ob basin

Russian forts in Siberia are multicomponent objects of the archaeological heritage; they include elements that are archaeological monuments on their own, outside of the fort context. These are cemeteries, trading quarters, churches, hoards, roads, etc. Studying the coexistence of a complex of objects within the archaeological context of a fort is an important and pertinent task at the present stage of research into the monuments going back to the period of the initial Russian assimilation of the lands of Siberia and the Far East. This article presents the results of interpretation of the archaeological excavations at the cemetery of Fort Umrevinsky, founded in 1703 on the right bank of the Ob River, 600 m to the southwest of the mouth of the Umreva River (Borodovsky, Gorokhov, 2009).

Description of burials and identification of the groups of burials

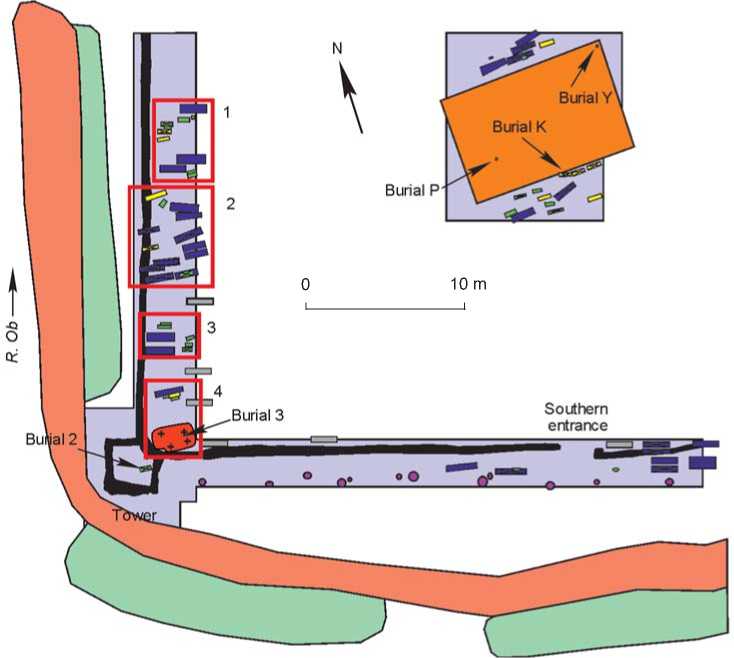

A cemetery was discovered on the territory of Fort Umrevinsky during archaeological investigations. In 2000, A.V. Shapovalov found a single burial on the northwestern edge of the courtyard of the fort. The excavations conducted by the present authors in 2002– 2006 and in 2015–2016 made it possible to trace the planigraphy of the cemetery along the western and southern palisade and at the ruins of a structure in the central part of the fort courtyard. In total, 83 burials have been investigated. The most interesting were burials 2, 3, K, P, and Y (Fig. 1).

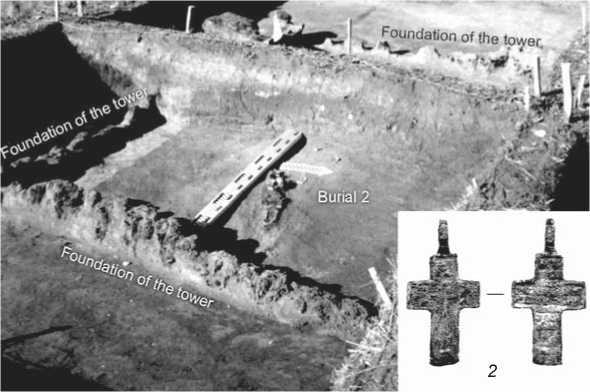

Burial 2 was located inside the perimeter of the foundation of the southwestern corner tower (Fig. 2, 1 ). The contours of the grave pit were identifiable in the

Fig. 1. Map of the investigated part of the cemetery at Fort Umrevinsky.

1 – burial of an adult; 2 – burial of an adolescent; 3 – burial of a newborn; 4 – collective burial; 5 – conserved burials; 6 – burials with baptismal crosses; 7 – ditch; 8 – embankment; 9 – excavation area; 10 – building; 11 – ditch of the palisade and of the tower foundations; 12 – pits from the posts of the cemetery fence.

Foundation of the tower.

°Undah6n

soil by decay from the wood slab where the infant’s body was placed. The size of this structure was 70 × 25 cm; the height of the surviving walls was about 5 cm. The wooden covering has completely decayed. The burial was located at the top of the natural layer. The

Fig. 2 . Burial 2 ( 1 ) and brass baptismal cross from burial 2 ( 2 ).

newborn child (according to the definition of the anthropologist D.V. Pozdnyakov) was buried in an extended supine position, head to the west, with legs crossed at the level of the shins. A brass baptismal cross lay face down under the left pelvic bone (Fig. 2, 2 ). Burial 2 was located apart from the main array of graves in the cemetery. There were no other graves inside the tower’s foundation contour.

Burial Y was found under the northern corner of the structure located in the central part of the fort courtyard (see Fig. 1). A chaotic accumulation of bones belonging to a newborn infant was located in the layer of buried soil beneath the debris from the destroyed building. Grave goods were absent.

Burial P was also discovered under the structure in the central part of the fort courtyard (see Fig. 1). It was under the layer of debris (fragments of raw bricks and baked bricks) resulting from the destruction of the stove, at the top of the natural layer. The burial was a chaotic accumulation of bones of a newborn. Grave goods were absent.

Burials 2, P, and Y have a number of common features. All of them are burials of newborns; all were made without deepening into the natural layer, and were located within the buildings (the rest of the graves were outside the buildings), at some distance from the other graves; while other infant burials were either near the graves of adults or were grouped together (see Fig. 1). The totality of the above features indicates that the practice of ritual burial of newborns was followed while erecting the structures on the territory of Fort Umrevinsky in the 1730s–1740s. The cribwork under which burial P was located, was an extension of the main part of the structure. Probably, this was the reason for the presence of two ritual graves under the same structure. Burials 2, P, and Y are the earliest graves found on the territory of Fort Umrevinsky, but they do not belong to the investigated cemetery, since they were performed for specific ritual purposes during the use of the fort as a military and administrative facility, while the cemetery began to emerge after the fort had lost its functions.

Burial 3 was located near the northeastern corner of the southwestern tower; it cut through the tower’s ribbon pile-pillar foundation at the place of the doorway (see Fig. 1). The size of the pit was 2.6 × 1.6 m; the depth in the natural layer was 33–61 cm. The burial was collective and layered. All the buried lay in an extended supine position, with their heads to the west. According to Pozdnyakov, nine persons of various ages and sexes (three women, two men, and four children under the age of two) were buried in the grave.

Burial 3 has a number of common features with the collective burial (57 persons) of dwellers of Fort Albazin (Artemyev, 1999: 113, 114). The thickness of the layer where the burials were located was 0.3–0.6 m in Fort Umrevinsky, and 0.3 m in Fort Albazin. The remains of men, women, and children were present in both burials. Both burials contained relatively little evidence of violent death: one lead buckshot and one pierced sternum (possibly by a bayonet) were found in Fort Umrevinsky, while two arrowheads and two lead bullets were discovered in Fort Albazin. The collective burial in Fort Albazin resulted from the death of a large number of people in a short period of time during a siege. The presence of common features suggests that the burial of nine bodies in Fort Umrevinsky also resulted from armed conflict. That burial could also be associated with the custom of burying poor people who died without receiving Communion once a year (Gmelin, 1751: 161; Belkovets, 1990: 105). An additional argument in favor of this hypothesis is the presence of a woman with a lead shot in the chest area among the buried women—she could have remained without Communion in the case of sudden death.

Burial K was adjacent to the southern wall of the structure in the central part of the fort (see Fig. 1, 3). The size of the burial pit is 1.20 × 0.45 m; the depth in the natural layer is 0.4 m. The remains of a coffin (1.03 × 0.35 m) were found in the grave. Parts of the coffin were fastened with iron braces and nails. The coffin was slanted to the right. The grave contained the skeleton of a child buried in an extended supine position, with his head to the west; his arms were crossed on his chest and he was oriented perpendicular to the western palisade wall. The remains of his uniform—felt cloth of dark color, golden galloon (floral ornamentation in the form of leaves and flowers, entwined with braids and red threads (Fig. 3, 3 )—were found in the area of his hips, wrists, and chest (Borodovsky, Gorokhov, 2009: 201–203, fig. 70–73). A brass baptismal cross lay under one of these fragments (Fig. 3, 4 ). The remains of leather boots remained on the bones. A coin of two kopecks value, minted in 1769 in the Suzun Mint, which lay with the monogram of Empress Catherine II upwards, was found to the left of the skull under the decay from the boards of the coffin (Fig. 3, 2 , 5 ). A denga coin of 1730, with the emblem of the Russian Empire facing upwards, was discovered on the foundations during the excavation in the southwestern fort tower. Given this fact, we may assume that the coin in the burial of the child who was wearing a uniform (and therefore, participated in civil service), placed with the monogram upwards, could have had symbolic meaning reflecting the belonging of the buried person to the state system of the Russian Empire. All of the arguments together make it possible to conclude that the coin was deliberately placed in the grave. First, 61 coins out of 62 (excluding the ritual finds) found in Fort Umrevinsky, originated either from the building in the central part of the courtyard or from the trading quarter. Only one coin was found outside the buildings on the territory of the fort courtyard. Coins were not present in other graves. Second, two kopecks is one of the largest denominations in the numismatic collection from the fort. Out of 64 coins, only five have equal or greater value; therefore the probability that a coin of exactly this value could find its way into the grave by accident is small. Third, the size of the two kopeck coin is quite large (Fig. 3, 5 )—it is harder to lose and easier to find such a coin while digging a grave. The burial was made sometime between 1769 and 1796. The lower chronological border is the year of minting, and the upper border is the end of the reign of Catherine II (if we consider the placement of the coin with the monogram of the Empress upwards as symbolically significant).

A number of features indicate that this grave was an “elite” burial: 1) the buried person was wearing

0 3 cm 0 3 cm

Fig. 3 . Burial K.

1 – general view; 2 – position of the coin in the burial; 3 – fragment of embroidery on the uniform of the buried; 4 – baptismal cross; 5 – coin.

an embroidered uniform; 2) the coffin had the largest number of iron parts (two braces and nails) compared with other examined coffins; 3) the coin in the burial was a symbol of belonging to the state system of the Russian Empire, and 4) the person had leather boots. The burial site should also have had a “prestigious” character. In the Russian Orthodox tradition, “elite” places for graves were located near the church building. It is known from the written sources that there was a church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Fort Umrevinsky, which was inside the fort walls (the exact location was not indicated) (Kamenetsky, Elert, 1986: 260). The building in the central part of the fort might have been a religious building, which is confirmed by the orientation of the structure strictly along the WE line. However, the set of objects from that structure does not make it possible to draw an unambiguous conclusion that it was a church. An indirect indication of the religious purpose of the building is three copper fasteners from books, possibly liturgical, which were discovered inside. The presence of books shows that literate people were associated with the building. In the mid 18th century, these, most likely, were either officials or clergymen. This structure differs significantly from the residential buildings at the trading quarters, and has “elite” features: a high ground floor, absence of a cellar, a considerable floor space (about 70 m2), large stove made of raw and baked bricks, as well as mica windows.

The studies of the cemetery at Fort Umrevinsky allow us to draw some preliminary conclusions concerning the planigraphy of the cemetery. There were no burials in the northern part of the excavation, in the place of the western palisade wall; only a single individual burial 1 was found in the northwestern corner. Four dense groups of burials can be distinguished in the southern part. The first group consists of three adult, two children’s, and six infant’s burials (see Fig. 1). Most of them (with the exception of three) were oriented strictly perpendicular to the western palisade wall. There were relatively few burials with baptismal crosses (see Table ).

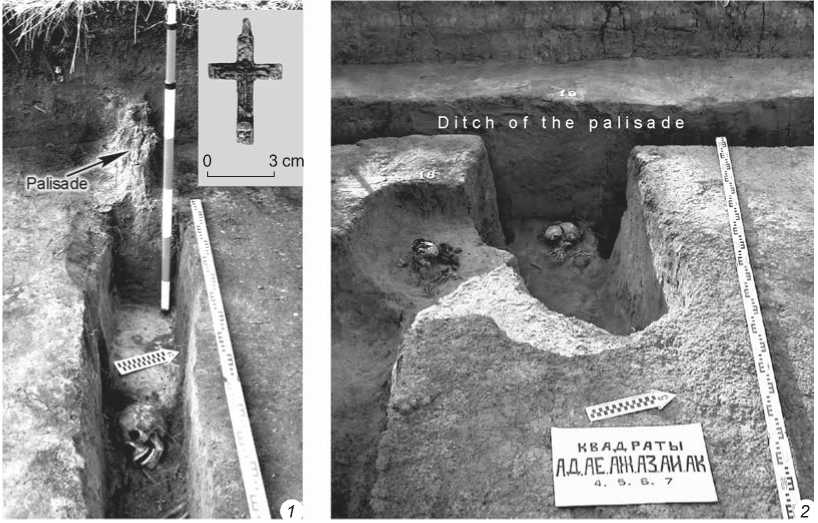

Group 2 includes 11 adult, two children’s, and two infant’s graves (see Fig. 1). All burials, except for two, were oriented strictly along the WE line. This group of burials shows the following features: three graves cutting through the ditch of the palisade (Fig. 4, 2), a relatively large number of baptismal crosses, and a small share of children’s and infant’s graves (see Table).

Group 3 consists of two adult and five infant’s burials (see Fig. 1). Almost all (except for one infant’s burial) were oriented strictly perpendicular to the western palisade wall. A baptismal cross was found only in one burial (see Table ). Adults and infants were buried at the same depth, anomalously small for this cemetery— 10–15 cm into the level of the natural layer.

Group 4 includes 13 burials united in two conglomerates (see Fig. 1). All the burials were oriented along the WE line. One (the northern) conglomerate consists of four graves (of an adult, adolescent, and two infants), located on three layers; the second conglomerate is the collective burial 3 described above (also three layers), which cut through the foundations of the southwestern tower. One third of the burials contained baptismal crosses (see Table ).

A group of burials near the building in the central part of the fort courtyard consists of six adult, six children’s, and seven infant’s burials. Almost all

Main features of the groups of burials

|

Group |

Orientation of burials |

Cutting through wooden defensive structures |

Share of burials with baptismal crosses, % |

Share of children’s burials, % |

|

1 |

Perpendicular to the western wall |

No |

18.2 |

72.7 |

|

2 |

West–east |

Yes |

46.7 |

26.7 |

|

3 |

Perpendicular to the western wall |

No |

14.3 |

71.4 |

|

4 |

West–east |

Yes |

30.8 |

53.8 |

|

Burials in the central part of the fort courtyard |

″ |

– |

42.1 |

68.4 |

|

Burials along the southern wall |

Parallel to the southern wall |

Yes |

36.4 |

18.2 |

Fig. 4 . Burial 46 in the ditch of the southern palisade wall ( 1 ) and burial 19, partially located in the ditch of the western palisade wall ( 2 ).

(except for burial K) were oriented along the WE line. The graves adjoin the outer side of the northern or southern walls of the structure or are located near them (see Fig. 1). The share of burials with baptismal crosses is relatively large (see Table ).

A group of burials along the southern palisade wall consists of nine adult and two infant’s burials. They are located on the outer and inner sides of the wall (see Fig. 1), and two (adult) burials were found directly in the palisade ditch (see Fig. 4, 1 ). All the graves were oriented parallel to the southern wall with a deviation from the WE line. Baptismal crosses were present in four adult burials (see Table ).

Discussion

The chronology of formation of a particular section of the cemetery at Fort Umrevinsky may be indicated by the orientation of grave pits, facts of cutting through the remains of wooden defensive structures by the burials, and a share of burials with baptismal crosses. According to the features described above, the identified groups can be united into two macrogroups (see Table). The first macrogroup includes groups 2, 4, and burials in the central part of the fort courtyard. It is characterized by the orientation of the graves along the WE line, cutting through the remains of wooden defensive structures by the grave pits (Fig. 4, 2), and a high share of graves with baptismal crosses. The second macrogroup consists of groups 1 and 3. It shows orientation perpendicular to the western palisade wall, absence of cutting through the remains of wooden defensive structures by the grave pits, and a small share of burials with baptismal crosses. A group of graves along the southern palisade wall has the features of both the first and second macrogroups (see Table).

The macrogroups might not have been formed synchronously. The first macrogroup can be dated by the group of graves in the central part of the fort courtyard. Specific features of the location of burials in this place were caused by the existence of a structure in this part of the site, since all burials, except the ritual ones, are located along the northern and southern walls of the building. According to the numismatic evidence, that structure was built in the 1740s and existed until the 1780s. Since the filling of the grave pits contained building debris, the burials were made there after the destruction of the structure, that is, not earlier than the 1780s. However, this could not have happened much later either, since the graves did not cut through the foundations of its walls and therefore the contours of the structure were still visible on the terrain at the time of the burial. Thus, all graves in this area, as well as burials of groups 2 and 4 (included in the first macrogroup) can be dated to the 1740s–1790s. According to the numismatic evidence, the trading quarters, which were located to the south and north of the fortifications, emerged in the 1740s and functioned until the 1790s. The burials of the first macrogroup may include the burials of its inhabitants.

The second macrogroup might have been formed both before and after the first one. Its earlier emergence is indicated by a low share of burials with baptismal crosses (assuming that in the first half of the 18th century, metal crosses were less accessible to the population of Fort Umrevinsky than in the second half of that century), and the fact that in some cases the burial pits were located close to the western palisade wall, but did not cut through its ditch. This means (if we exclude random coincidence) that the wall still existed at the time of the burials (see Fig. 1). Orientation of the graves perpendicular to the western palisade wall may indicate both earlier and later period of burials. While digging a grave pit, the workers probably chose its direction in accordance with the building in the central part of the fort courtyard (possibly a church), as standing along the WE line. Consequently, such a landmark was absent before the appearance of that building and after its destruction. However, it was known that the Ob River flows northward (the walls of the fort were parallel or perpendicular to the river), thus it could also have served as a landmark. It was also possible to orientate new graves in accordance with previous burials. However, the high density of burials led to rapid merging of the embankments and the loss of their individual characteristics. The graves became overgrown with thick vegetation in the summer and were covered with snow in the winter, which would make it difficult to determine their orientation.

There are more arguments supporting the hypothesis that the second macrogroup emerged later than the first one. It has a higher percentage of children’s and infant’s burials (prior to the appearance of the settlement, there was probably only a temporary garrison consisting mainly of adult men in the fort). In the first half of the 1730s, Fort Umrevinsky was reconstructed (the towers were built). Accordingly, it must have functioned as a military facility and not as a cemetery; therefore, there would have been no motivation for making burials in the courtyard of the fort. All burials in coffins (a later structure than wood slabs), which were discovered in the excavation pit along the western palisade wall, were oriented perpendicular to the wall (a typical feature of the second macrogroup). Graves of group 1 were the extreme northern burials in this excavation pit. There were no further burials, although there was space available for them. This edge of the cemetery was probably one of the last to emerge. The orientation of the burials of the second macrogroup is the same as the graves in the excavation along the southern palisade, which in some cases cut through the palisade ditch and were located outside the fort courtyard in the space between the palisade wall and the later fence of the cemetery, which runs parallel to it. Consequently, this group of burials appeared after the destruction of the southern palisade wall, that is, in a relatively late time. According to the totality of the arguments, it is more likely that the second macrogroup was formed later than the first one.

It seems that the cemetery did not extend beyond the system of ditches and embankments. This is indicated by some indirect evidence: 1) in the areas where the fence line of the cemetery was found within the boundaries of the earth defensive structures, there were no burials beyond the cemetery fence; 2) analysis of the geophysical map of the area of the fort and the adjoining territories also confirms the absence of burials outside the earth defensive structures in their direct vicinity (Gorokhov, 2006); and 3) as excavations have shown, a significant area of the inner space of the fort was not occupied by the cemetery, or the density of burials was such that there was enough space for burial places between the existing graves.

Probably, at the first stage of formation of the cemetery, the palisade wall remaining from the fort functioned as a fence. Over time, it came into disrepair and was partially disassembled. At a certain point, the burials that were made along the western wall of the fort, started to cut through the ditch of the palisade. The new fence of the cemetery was built in the space between the palisade wall and the system of earth defensive structures, as is the case in the investigated section along the southern palisade, where the fence of the cemetery was located 1–1.5 m to the south of the palisade wall (see Fig. 1).

The emergence of a cemetery on the territory of Fort Umrevinsky was not accidental. A number of factors make this place preferable for setting up a cemetery. A cemetery and a fort have similar structural elements, which would continue to exist after the fort ceased to function: a system of ditches and embankments, and in our case, the palisade wall. In the late 18th century, wooden structures of forts, which became unusable, could sometimes be reused in the construction of cemetery fences. For example, the peasants who came to the gathering in 1791 wanted to use the wooden defensive structures of Fort Berdsk for that purpose (Smetanin, 1983: 14). The importance of ditches which were already in place for arranging cemeteries in the vicinity of Fort Umrevinsky is confirmed by the cemetery in the village of Shumikha (Bolotninsky District of the Novosibirsk Region). It is located 2 km north of the fort, on the elevated ground of a medieval fortified settlement, surrounded by a powerful system of earth defensive structures, which until now are clearly visible on the terrain. Fortified settlements and forts were built on elevated and dry places, which was also important when choosing a place for a cemetery. Another important factor was the presence of the wooden church of the Three Holy Hierarchs. The exact location of the church has not been not established, but it is known from the written sources that after the fort had lost its defensive significance and came to desolation, the church continued to function (Minenko, 1990: 51).

Conclusions

A cemetery on the territory of a fort is a relatively traditional phenomenon. A similar situation was in the Bratsk, Ilimsk, Krasnoyarsk, Albazin, Zashiversk, and Irkutsk forts (Kradin, 1988: 121). In Ilimsk, the cemetery emerged on the western part of the inner space of the fort (Molodin, 1999: 113–114); in Krasnoyarsk in the southwestern corner of the fortified trading quarters (Tarasov, 2000: 150); in Zashiversk in the church (Okladnikov, Gogolev, Ashchepkov, 1977: 84, 123), and in Fort Albazin, burials were concentrated in the central part (Artemyev, 1996). In each particular case, it is necessary to take into account the reasons for the emergence of cemeteries on the territory of the monuments for correct interpretation of the specific features of their emergence. Thus, the location of the cemetery in the central part of the courtyard in Fort Albazin was associated with a siege and the subsequent abandonment of the fort for a short period of time. A different situation occurred in the Ilimsk and Krasnoyarsk forts. The cemeteries there were formed in peacetime over a long period along the palisade walls. Many of the Ilimsk burials cut through defensive structures, which had fallen into disrepair. Judging by the discovered accompanying coin of 1746, a single burial in the church of the Fort Zashiversk was made at the time when the church had existed for almost half a century (Okladnikov, Gogolev, Ashchepkov, 1977: 123).

The study of the internal structure of the cemetery and its relationship with other structures of the fort has made it possible to establish the sequence of the formation of various sections at the cemetery, and to significantly clarify the history of Fort Umrevinsky. The question as to where the founders and first settlers of the fort were buried, who died before the emergence of the cemetery under investigation, still remains unsolved.

It seems promising to compare urban and fort cemeteries with rural cemeteries and monastery graveyards for identifying their specific features caused by the culture of the settlements to which they belonged. At present, a sufficient source base has been accumulated for initiating comparative studies. In recent decades, such Russian rural burial monuments as Staroaleika II, Izyuk I, and the Gornopravdinsky burial ground have been studied (Kiryushin et al., 2006; Tataurova, 2010; Zaitseva, 2008), as well as cemeteries at the Tomsk St. Alexis Theotokos monastery, Tobolsk Abalak monastery, and Verkhoturye St. Nicholas monastery (Bobrova, 2017; Danilov, 2012; Kurlaev, 1998).

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 14-50-00036).