The development of reading and writing based on Montessori educational materials

Автор: Yakovleva E.L.

Журнал: Евразийский гуманитарный журнал @evrazgum-journal

Рубрика: Лингводидактика

Статья в выпуске: 4, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The study presents the results obtained in the long-term project “Taiwan preschool English classes: Montessori and non-Montessori approaches”. The article focuses on the analysis of the Montessori materials commonly implemented for teaching very young learners of English. Their teaching materials (e.g. vowel matching cards, sandpaper letters, sentence analysis signs) help to develop all four skills of English at the very early age. Furthermore, they let the kindergartners get acquainted with some metalinguistic knowledge of phonology (e.g. phonics, sound blend), syntax (sentence structure with parts of speech), morphology (building words) etc. Such deeper learning of English as foreign language by very young learners in a playful way leads to the fact that 4-6 years old Taiwanese children have a good foundation of basic English in speaking, reading, listening and writing, while growing in non-naturalistic environment of English.

Literacy, montessori educational materials, ostensive definition, principle of isolation, reading, (cursive) writing

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147242795

IDR: 147242795 | УДК: 811

Текст научной статьи The development of reading and writing based on Montessori educational materials

Background

Bilingual kindergartens are a very common phenomenon in Taiwanese society since many decades. The intensity of English learning curriculum there differs from a few hours per week to a half day taught in English (besides Chinese). In fact, bilingual kindergartens with the foreign teachers are prohibited in Taiwan. However, there is a loophole in the law that allows cram schools to teach English; consequently, kindergartens and nurseries change their status to a cram school hiring foreign teachers. The fact cannot be denied that there are many bilingual kindergartens in Taiwan that attract parents with different English programs.

One of the programs for teaching English is implemented in Montessori kindergartens. There are only a few Montessori bilingual kindergartens in Taiwan probably because of their higher tuition fees. However, they are quite popular, especially among well-educated Taiwanese parents because Montessori kindergartens offer a very different learning approach for each child individually. Montessori education fosters a rigorous and self-motivated growth for children, involving their natural interests and individual activities guided by highly trained teachers if needed. Many teachers are familiar with the Montessori child-centered approach, but they don’t know that this method can also be applied to English teaching and learning. It provides hands-on learning in a sufficiently supportive and well-prepared learning environment. Montessori education develops real-world skills (set the table, water the plants etc.). The method was started in the early 20th century by Italian physician Maria Montessori and has proven its efficacy worldwide. Since this approach appeared to be effective for English learning, as the kindergarten children have demonstrated through their extensive vocabulary and developing reading ability at the age of 5-6 years, it is highly interesting to elaborate on Montessori teaching materials and learning process of English.

Montessori Educational Materials

The variety of Montessori educational materials is diverse, and its choice depends on each Montessori educational institution. Here are some of the educational materials commonly used for the Montessori English learning (ref. pics. 1-13):

– Phonics Books (pic. 1)

– Sound Boxes (pic. 2-3)

– Sandpaper Letters (pic. 4-5)

– Vocabulary Flash Cards (pic. 6)

– Vowel Matching Cards (pic. 7)

– Phonics Sounds Cards (pic. 8)

– Sentence Pattern Signs (pic. 9-11)

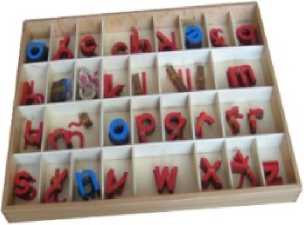

– Movable Alphabet (pic. 12-13)

These educational materials will be introduced in detail below, and the working process employing them will also be described and assessed. Many of these exercises are interwoven and develop different linguistic skills of phonology, vocabulary, grammar, syntax through listening, speaking, reading, and writing as well as the kinesthetic abilities (i.e. sensory) along with concentration. It should be noted that Montessori English classes described in this study may differ from Montessori English classes adopted in English-speaking countries because of their different purposes in terms of L2 (second language learning) vs. L1 (first language acquisition), respectively.

a. Phonics Books

pic. 1 Phonics book

The first English class in the Montessori kindergarten started with discovering the background of the English knowledge of every child since it is crucially important to group the children according to their ability and to determine the appropriate teaching strategy for each small group of 2-3 children. For this purpose, the English alphabet was used to check the children’s knowledge of English letters and also their phonics, i.e. the sound of letters; e.g. the sign A was called by children as [æj] for letter and /a/for phonics. Since the name of a letter has less use for a three-year-old for speaking and later reading, the children first learn the sound of the letter (phonics) as English native speakers also do (ref. Lillard 1988, p.128). For better learning, the children said every alphabetic sign in the following rhythm: letter – letter – phonics – phonics – phonics, i.e. [æj] – [æj] – /a/ – /a/–/a/, where the phonics is pronounced three times instead of two times for the corresponding letter. It implicitly indicates that the phonics are more important in the Montessori method than the letters which are traditionally firstly learned in EFL. It is useful that children learn the pronunciation of letters (alphabet) and also their corresponding phonics (sounds) since both of them are used in the word’s pronunciation. If they knew only phonics or only letters, it would cause them to be perplexed about the inconsistent pronunciation of some vocabulary, especially in the reading process. McBride-Chang and Treiman (2003, p.142) also emphasized the importance of phonological skills in initial reading acquisition of language. Almost all children of the Montessori kindergarten found no difficulty with the spelling of a word, i.e. they knew most of the phonics and letters as well, despite the fact that some students mixed up a pair of similar voiced or voiceless sounds like p vs. b. This exercise is also the first teaching step for newcomers who are not familiar with the Montessori method.

The next activity was based on the phonics books practicing a certain sound. This conception underlies Montessori’s Principle of Isolation with its focus on new knowledge (ref. Lillard 1988, p.128). Every phonics book used in each English class consists of a picture on one side and a corresponding written word on another side; there are a total of five or six words for one phonic sound (pic. 1). Such isolation helps to expose the child to the reading offering him indirectly only one option of word recognition through letters. Then the teacher showed a picture, named the word, and the children repeated after her. The astonishing point in this process was that most five-or-six-year olds tried to read the word, especially the one- or two-syllable words (e.g. bat, che-rry) and then gave an answer, i.e. the written word (not the depicted object) was a primary reference for them. On the contrary, the youngest and middle group children first referred to the picture and named it, by using their visual memory. It indicates that the reading process, which is emphasized in the Montessori method for ESL, usually starts at the age of five or six years old. It is interesting to mention that Taiwanese children in the Montessori kindergarten start to read English earlier than their native Chinese language because the latter requires several years to learn the Chinese characters. The children learn to read English by sounding out the letters and combining them into a syllable, then forming syllables into a word. The concept that the child’s ability to pronounce the sequence of connecting letters into syllables, and only then forming syllables into words was also emphasized by the great Russian writer Leo Tolstoy half a century before Montessori’s works and it is still timely to this day (ref. Tannikova 2007, p.16). This process indicates that children, who have already begun the reading process, implemented the alphabetic skills of name (letter) and/or sound (phonics) condition in contrast to the visual condition. Taiwanese children often needed to see the written word first in order to decipher it and spell it as they couldn’t perceive some words aurally.

It is necessary to mention that the whole environment of the Montessori kindergarten, i.e. surroundings with the written words (e.g. labeled objects), assists the children in naturally acquiring reading skills in contrast to force-fed reading. Even if the reading process is not an (primary) objective of teaching process in a non-Montessori kindergarten, every opportunity should be used to expose the child to reading, e.g. to introduce the new vocabulary on flashcards through reading the written word syllable by syllable, to create the print-rich environment of the kindergarten etc. This idea also supports Cameron’s (2001, p.19) principle: “children’s foreign language learning depends on what they experience”. Such an atmosphere is favorable for the reading readiness approach which, consequently, contributes to the emergent literacy approach (ref. Tafa 2008, p.164). In the bilingual kindergarten, literacy can also be acquired through play (e.g. “in the store/hospital”), whereas different objects (e.g. fruits, paper money) used in the play would be labeled in the target language. This idea is commonly used in monolingual kindergartens and is a natural process of acquiring first language through playing (Owocki 1999). The importance of labeling words in L1 and/or L2 in the classroom has been emphasized by many scholars (Cameron 2001; Lillard 1988; Pinter 2006). Even if the children will use their native language in the play, the visual representation of the written form of the foreign language will expose them indirectly to the literacy process of the target language. Furthermore, “children can learn concepts or words in the second language that they do not yet know in their first language. This is natural in a rich linguistic environment” (Pinter 2006, p.84).

In the Montessori method the teacher doesn’t subconsciously use the verb ‘read’in the requests and should rather utter such indirect requests in form of questions as, “Can you tell me what this is?” without forcing the child to complete the reading. In fact, children are aware that reading and writing are necessary and go hand-in-hand. There is no “particular time when children should begin to read”, and the reading is more complicated here than the writing, which starts earlier, as will be shown later, because it is a less complicated psychological activity of the child (ref. Lillard 1988, p.123). The reading process requires the understanding of sounds’ meaning contrary to writing which is often done by the child automatically, i.e. without considering the meaning, especially of written letters or syllables (ref. Tannikova 2007, p.14).

The Montessori education theory asserts that reading comes in a full form, i.e. as “total reading” which couldn’t be observed in our case study since the five-and-six-year-old children could read only simple words consisting of one or two syllables and they could read not all easy words. Besides, when the word consisted of three syllables, the five-and-six-year olds did not try to read the whole word, instead they tried to guess the word after reading only the first and/or second syllable (e.g. fla -min-go). The children had learned this word before, so they read only the first syllable, gave up reading the whole word, and pronounced the whole word immediately by guessing. It is natural that due to the complexity of the reading process, at its initial stage some children try to guess the word based on the provided image or on the first letter(s) of the word instead of reading it. Only if their guess was wrong, would they try to read again. Therefore, following the Montessori’s Principle of Isolation, the teacher showed only one syllable at a time to facilitate the visual reading process of children and prevent them from guessing. In Taiwan’s Montessori kindergarten, the children usually practiced reading only with single one and two-syllable-words with a corresponding picture, and not with phrases or sentences as happens with native speakers at the same age. Such simplicity could be grounded in the fact that the transition to the reading process is a difficult task; therefore it is crucial to awaken and sustain the child’s interest in reading.

After some time (ca. 3-4 months), when all phonics books had been practiced by children, they were assessed and classified by the researcher into the following three categories of their degree of difficulty:

-

1. Easy phonics: b, d, g, h, k, m, n, s, t, v, w;

-

2. Medium difficulty phonics: a, c, e, j, p, r, y, z;

-

3. Difficult phonics: i, o, q, u, x, y.

The degree of difficulty means the ability of the children to read the word or to remember it with reference to its picture. When the children could name most words of one phonics book promptly, it was defined as easy. When only about half of the words could be identified, this phonics book was classified as medium level of difficulty. The phonics book was classified as difficult when the children had difficulties naming most pictures or reading most of the words. Here are some examples of most difficult words for children, especially for the youngest group, due to the hard pronunciation, specific meaning or rare frequency of use: anchor, apron, astronaut, axe, garage, jigsaw, kettle, kitchen, ladder, leaf, octagon, optometrist, pillow, rake, rocket, rod, scissors, tag, windmill, xylophone, yolk. However, it is erroneous to assume that the children hardly could learn any difficult words. In contrast, they knew such complicated words as church, checkers, chess, grandparents, plunger, ruler, skeleton, umpire, x-ray that normally aroused their interest or seemed fun due to the word’s special meaning or its periodic use. Some phonics books have been considered easy when the children could easily recall the depicted objects, e.g. the phonics book ‘B’ with bag, banana, bear, book, bus; the phonics book ‘C’ with can, cap, cow, cup; the phonics book ‘G’ with grapes, girl, goat, gorilla. The easy vocabulary often refers to the animals or fruits that children learn traditionally as primary words. It is to mention that such exercises as pointing to an object also serves as a good listening comprehension practice for children. In contract, one phonics book, # 19 i,contained the difficult word igloo with the meaning ‘snow house’ and another had the abstract word invitation, which rather should be replaced with ice cream as a child’s favorite treat. Next, the children giggled when learning such words as udder (the part of cow that hangs down between its back legs and that produces milk) and underwear, but they could remember it quickly.The children also easily learned the word ugly because of the picture with a funny ugly mask. It should be accentuated that the classification of phonics introduced above cannot serve as a reference for further studies because it was based only on the phonics books available in the Montessori kindergarten mentioned above. The phonics books can contain different words with different pictures. The right choice of the appropriate vocabulary, i.e. meaningful, non-abstract, preferably short, catchy and useful words, with clearly referential and interesting pictures is indispensable for an easy and fun learning process in order to keep the children more concentrated and motivated.

b. Sound Boxes

pic. 2 Sound box

pic. 3 Sound boxes

As well as by the phonics books, some the sound boxes’ vocabulary was also too hard for children to remember due to its hard pronunciation (especially compound words), specific meaning or rare frequency of use, e.g. apron, anchor, angel, jack-o-lantern, jewel, nightgown, paints, sailboat, toothpaste, turkey, tub, velvet, vest, well, whistle, yacht, yak, zigzag. For that purpose, in this researcher’s class, the vocabulary has very often been practiced through a simple sentence pattern such as: I like k oala. Some advanced children even combined some objects from the same sound box making a sentence like “Gorilla eats grapes,”and showing this action through the objects. One child made a sentence from some written words with the same initial sound, e.g. The f eather f alls.This indicates the child’s readiness for language learning on the sentence level, including vocabulary, grammar, and syntax.

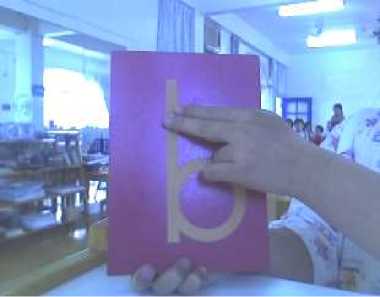

c. Sandpaper Letters

pic. 4 Sandpaper letters

pic. 5 Sandpaper letters

For that reason, in English class, the vocabulary has very often been practiced through the simple sentence pattern such as: “I have a book,”“I like bear,”“I want ice-cream,” as these verbs are commonly used. Through these simple syntactic constraints, the children practice vocabulary, grammar, and syntax transitioning from the word or phrase level to the sentence level, which is absolutely necessary for a complete communication. It helps language learners retain vocabulary easily and use it in real life communication. The children like to say such sentences expressing their own preferences and it often has a “ripple effect”, whereas almost every child wants to say a sentence expressing his own opinion.

After the sound box was placed back on the shelf as a necessary disciplining aspect of Montessori’s method, the preschoolers performed the act of finger tracing of the same phonics practiced in the phonics book, while repeating the sound. The sandpaper letters (pic. 4-5) for finger tracing are mounted on smooth boards approximately fifteen centimeters high and divided into the vowels mounted on blue boards and the consonants on pink ones that prepares the children for earlier phonological distinction based on visual distinction (Lillard 1988, p.128). Such sensitive touch exercises help the children of the youngest and middle group control their hand movements. As the first formal introduction to the written language, it was the easiest exercise considered as mechanical quick action, especially by elder children, where they felt bored and considered it unnecessary (because the elder children had already passed their sensitive period). It should be stressed that the finger tracing of the sandpaper letters is designed for using tactile sense during the child’s sensitive period for touch and sound, i.e. until the age of four years, for the muscular memory. However, the light finger tracing technique, namely tracing with two fingers (index and middle finger)1 of the child’s dominant hand simultaneously pronouncing the sound, and the correct tracing sequence (e.g. from up to down, from left to right) should be sustained for the furtherance of proper writing skills. Therefore, this exercise should be done in a slow and deliberate movement (ref. Lillard 1988, p.128). Although the children considered finger tracing to be easy, they were sometimes corrected due to their incorrect direction of finger tracing, especially among the youngest group of children. Some children repeated the finger tracing of a sandpaper letter twice on their own initiative, probably for better learning of the tracing direction. On the other hand, Lillard (1988, p.129) mentioned that the exercise with the sandpaper letters should be considered as practice of sound and its corresponding shape of the letter and not as a writing exercise. Furthermore, it is to mention that some of the children were tracing letters of the word by themselves without any teacher’s prompts. This implies that, if finger tracing is practiced periodically, it stimulates the children to do it; however, excessive use could make the children feel bored during the activity. In general, tracing letters is a good practice to allow the students to become more familiar with the letters and to retain the visual form and spelling of a word that contributes to the literacy development in its turn.

d. Vocabulary Flash Cards

pic. 6 Vocabulary flash cards

This educational material (pic. 6) lets the kindergartners learn different vocabulary through the picture and its written word separately on both sides of the card. Furthermore, the learners practice different sounds, mostly vowels. The children either name the word using visual memory or they read the one-syllable word using reading skills (without seeing the picture). These cards expand the child’s vocabulary and practice his reading skills and the pronunciation of certain sounds as well.

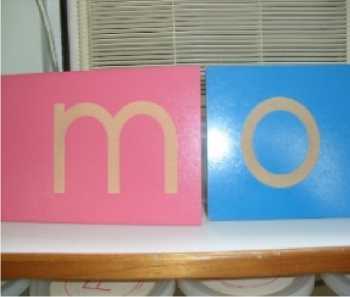

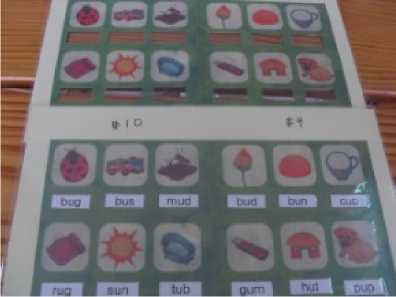

e. Vowel Matching Cards

pic. 7 Vowel matching cards

These cards (pic. 7) focus on the pronunciation on vowels, namely the same vowel sound in different one-syllable words (e.g. /ʌ/ – bug, bus, bun). Furthermore, the kindergartners learn different vocabulary through the picture and its written word below. In this exercise, the children mostly read the one-syllable word. In addition, they learn new vocabulary referring to the picture. These cards let the children practice the phonics through reading and expand their vocabulary.

f. Phonics Sound Cards

pic. 8 Phonics sounds cards

Through these cards the children also practice different phonics and blends (consonant clusters like br ick). Besides reading, this educational material (pic. 8) lets the kindergartners also learn different vocabulary through the picture. The children either name the word using visual memory or they read the one-syllable word on the other side using reading skills (without seeing the picture). These cards expand the child’s vocabulary and practice his reading skills and the pronunciation of certain sounds as well.

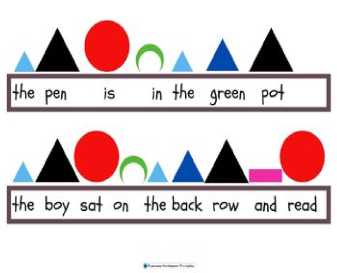

g. Sentence Pattern Signs

pic. 9 Sentence pattern signs

pic. 10 Parts of Speech

pic. 11 Sentence structure

This metalinguistic practice has been also implemented into the Montessori learning process. The very young learners have astonishingly developed the analytical skills in the syntactical analysis of the simple sentences. Through different geometrical figures in different colors the Taiwanese children as ESL learners analyze the basic SVO-structure of the sentences in English when they mark the parts of the speech, e.g. noun with black triangle or verb with red circle (pic. 911). In this exercise, the teacher writes a simple sentence and the child places the figures under each word to identify the part of speech. The primary knowledge about syntax rules and the recognition of the parts of speech in English makes the Chinese learners aware of the typical sentence structure that is sometimes problematic to the Chinese adult learners of ESL, e.g. to distinguish between adjective and adverb or to combine adjective with noun or adverb with verb.

After the exercises mentioned above, the children in the Montessori kindergarten anticipated the last exercise, namely writing, which develops in an early period. This complex action requires coordination between both hand and mind, proper handling of the pencil, and the ability to reproduce the graphic symbols in the available space. The children were indirectly prepared for handwriting through different Montessori educational materials: The pincer grip necessary for grasping the writing instrument was practiced through the cylinder blocks fitted with little knobs that the child has to pick up using the pincer grip which requires a light touch of the lifting hand. The sandpaper letters are conducive to the writing ability, while the child learns the graphic symbols by sight, sound, as well as touch. The tactile-muscular memory plays a crucial role for learning the letters, especially in the sensitive period between 3 to 4.5 years. Used by a local teacher, the metal insets and frames of geometric figures1 also train one hand for the exact, correct writing in various angles and directions, for wielding a pencil and prepares the other hand for holding down the paper firmly during writing. The movable alphabet described below is also a good preparation for the writing process, which normally “… is not developed gradually, but in a sudden outburst;” (Montessori 1985, p.228ff.). According to the Montessori method, the best time for children to start with writing is age 3 as it is considered their most sensitive and teachable period. “And Montessori seizes the period of sensitivity to prepare the young muscles for later hand writing.” The use of pencil instead of pen is common and recommended by Montessori approach because it is easier to erase and correct. Besides, the writing movement is softer with a pencil than with pen, which is important for the initial stage of the writing process.

Referring back to the sensorial exercises of the Montessori program, together with the colorful magnetic movable non-Montessori alphabet consisting only of capital letters (pic. 14), different from the Montessori movable alphabet consisting of both upper and lower case letters and divided into two colors, namely red for consonants and blue for vowels (pic. 12-13), the writing practice was supplementary introduced into the Montessori English class.

h. Movable Alphabet and Writing Practice

pic. 12 Movable alphabet

pic. 13 Building words

pic. 14 Magnetic alphabet

The teacher or the children chose the same word for all groups from a studied phonics book for the writing practice. Normally, it was a kind of word that was challenging to remember, or one which the children liked because it was cute, interesting, or useful (e.g. hug, mug). After the word was named and spelled by the children, every child was appointed to find one or two letters of that word, and then all of the children (2-3) readily spelled out the word together in left-to-right progression. Despite that the youngest and some four-year old children couldn’t read or write the word yet, they were able to do the mechanical reproduction of the word by remembering the letters and its respective sounds (Lillard 1988, p.130). In order to avoid fighting, the children were advised to search for the letter(s) only with one hand and one after another. Although this would seem to be an easy task, this exercise revealed some difficulties even for the stronger pupils because it requires more concentration and a quick reaction to find a letter among many other letters.1 Roughly a half of the children often couldn’t find a letter quickly by themselves, and then only with help of other children.2 It indicates that the expressed strength of every child is different, e.g. some had a better visual or muscular memory, others an aural (auditory), tactile, or motor memory. However, some children have improved their ability of word puzzling after several months of exercise, i.e. they could then also find the letters quickly by themselves.

After the word was composed, the teacher wrote this word on a small white board to demonstrate the writing direction and technique. While this exercise was considered as writing practice for the eldest and middle group, it was considered rather as a creative process of drawing by younger children, where some of them often asked for help to write the word by marker on the outlined white board. After the children wrote the word, they pronounced it, and then erased the board cheerfully. A few children erased the white board not as quickly, but slowly letter by letter, pronouncing each letter for better learning of the word.

The main problem in this exercise was the type of letters, i.e. most children tended to write in the block (not cursive) letters as shown in the book. Attention was also paid to the writing direction (e.g. from up to down, from left to right). Even when the direction of the letter’s finger tracing was completed by a child correctly, sometimes his direction by writing the same letter was wrong. To write within the outlines on the white board and to write the letters of the same size was also a challenge for some of the youngsters. If the child wrote the letter wrong, i.e. wrong direction or outside of outlines, the teacher asked him to write this letter again until it was correct. It is also astonishing that the eldest group of preschoolers was able to write the word without looking at it, while the teacher was spelling the word, i.e. they were very familiar with the alphabet and phonics. The Montessori teacher often wrote and cut off different labels of words for different games in the child’s presence in order to demonstrate to the child the slow and careful writing process. The fact that the children were disappointed when this writing exercise was omitted on rare occasions indicates that the writing practice as a part of the English class designed in an interesting way also creates a fun learning process for children. This strongly convincing fact should also motivate non-Montessori bilingual kindergartens to implement teaching English basic literacy into their curriculum.

Going back to the question regarding cursive writing, according to the Montessori method, much of the educational materials (e.g. the sandpaper letters) use cursive letters. The preference of the cursive type of letters is explained by different reasons: first, the children can practice more streamline movements instead of the abrupt movements of the printed letters, where the former is required for writing; second, “there is a more natural linking together of hand and mind in the forming of cursive letters” what is easy to remember (ref. Lillard 1988, p.128). However, many educational materials don’t display the usual style of cursive writing compared to the alphabet of the cursive letters shown on their other materials. Despite the flowing character of letters, the educational materials actually contain a mixture of cursive letters and printed letters what often appears in the writing style of the adult native speakers of English. It is an interesting fact that when the teacher wrote a word consisting of fully cursive letters, the children were confused and/or began laughing about it, because they were not accustomed to this type of lettering. It should be mentioned that the cursive letters might be considered less important for language learners in Taiwan, where the cursive writing in English is even not allowed, especially during the examination. Based on the explanations above, in the researcher’s opinion, the Montessori method cannot assert that it teaches the cursive letters through their educational materials; therefore, it desires constancy of writing styles for clearer educational guidelines.

Conclusion

Montessori educational materials, which fulfill a function of ‘educational toys’, are proven to be highly effective in teaching English as native or foreign language for the very young learners. They help to develop not only the English oracy that is a common primary goal in ESL, but also the literacy. Montessori materials employ different senses and memories in the early development of the child. They also develop analytical linguistic skills. It is impressive when the kindergartners start to read and write easy vocabulary of English that is a foreign language to them.

Список литературы The development of reading and writing based on Montessori educational materials

- Cameron L. Teaching language to young learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 288 p.

- Lillard A.S. How important are the Montessori materials? // Montessori Life. 2008. Volume 20. Issue 4. P. 20−25.

- Lillard P. P. Montessori: A Modern Approach. NY: Schocken books, 1988. 137 p.

- McBride-Chang C., Treiman R. Hong Kong Chinese kindergartners learn to read English analytically // Psychological Science. 2003. Vol. 14. No. 2. P. 138−143.

- Montessori M. The Discovery of the Child. India: Kalakshetra Publications (published posthumously), 1985. 398 p.

- Owocki G. Literacy through play. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1999. 138 p.

- Pinter A. Teaching young language learners. Oxford: OUP, 2006. 192 p.

- Rule A. C., Welch G. Using object boxes to teach the form, function, and vocabulary of the parts of the human eye // Science activities. 2008. Volume 45. No. 2. P. 13−22.

- Tafa E. Kindergarten reading and writing curricula in the European Union // Literacy. 2008. Volume 42. No. 3. P. 162−170.

- Tannikova E. B. Montessori-groups in preschool educational institutions. (Transl. from Russian). Moscow: TZ Sfera, 2007. 80 p.

- Tavil Z. M., Uşisaģ K. U. Teaching vocabulary to very young learners through games and songs // Ekev Akademi Dergisi Yil. 2009. 13Sayi. 38. P. 299−308.