The emergence and formation of a proto-urban civilization in Azerbaijan: certain issues in the transition to class society

Автор: Jafarov H.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.49, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The objective of this article is to clarify certain important issues relating to early urban culture. The complexity of the task stems from the absence of early written sources. This is why the study draws on archaeological materials. It especially focuses on the incipient proto-urban sites—the sources of the proto-urban culture. Certain Bronze Age settlements in Azerbaijan meet the criteria of the early urban civilization. On the basis of the facts cited here, hypotheses about the factors underlying the emergence of proto-urban centers (the harbingers of the first class societies) are put forward. The main features of proto-urban settlements are surface area, structure, fortifications, population size, and population density. The evolution of crafts in such centers is reconstructed along with other aspects. It is argued for the first time that nearly all cultural values typical of the advanced ancient Near Eastern centers were borrowed by South Caucasians. Monumental Late Bronze Age burial mounds of Karabakh are viewed in the context of proto-urban evolution. The idea that elite burials were connected with early urban centers is based on the fact that only powerful chiefs of large tribal unions and early class societies could afford monumental burials on such a scale.

Proto-town, Azerbaijan, Karabakh, Nakhchivan, Kultepe, Uzerliktepe, Garatepe

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146268

IDR: 145146268 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2021.49.2.064-071

Текст научной статьи The emergence and formation of a proto-urban civilization in Azerbaijan: certain issues in the transition to class society

The problem of the emergence of the so-called early urban culture is one of the complex historical issues of the preliterate period; it has long been discussed in archaeological literature (Adams, 1966: 48–75; Adams, Nissen, 1972: 156–210; Masson, 1967; 1976: 65–70, 95–148; 2004) and became a debated topic among Azerbaijan archaeologists (Aliyev V.H., 1991: 23–24; 1992: 24–28; Jafarov, 2000: 69; 2020: 133– 134). Scholars have proposed various hypotheses regarding the role of the early proto-urban culture, its origins and development, as well as initial stages of the settlements of the early urban type. The criteria for identifying such stages include the structure and area of the settlements, presence of defensive structures, number and density of population, development level of craftsmanship, presence of artisans’ quarters, instances of exchange and trade with the outside world, etc. (Masson, 1976: 65–70).

A great role in this process was played by the first large social divisions of labor—separation of agriculturalists from cattle breeders in the 3rd millennium BC and artisans from other manufacturers in the first half of the 2nd millennium BC, emergence of merchants as intermediaries between producers and consumers from the artisans’ circle, and unification of numerous tribes into single entities and formation of large tribal alliances—the harbingers of class society, etc. The process of property differentiation in the Southern Caucasus, which began

in the Late Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age, gradually intensified in the 2nd millennium BC and reached a high level in the Late Bronze Age.

Noteworthy is also such a transitional stage in the history of ancient society as the so-called military democracy. In our opinion, almost all peoples who passed through the period of disintegration of the tribal system had that stage. At this time, the power of military leaders increased; wars, which eventually acquired a predatory nature, became more frequent. Constant warfare contributed to the development of military techniques, improvement of offensive and defensive tactics, and fortification of settlements with earthen ramparts, stone walls, and ditches (Reder, Cherkasova, 1979: 79–80). In classical understanding, the emergence of the military democracy, which was one of the vivid indicators of early class society, occurred in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, and according to some scholars, in the 3rd millennium BC (Brentjes, 1976: 62).

In the recent period, the Azerbaijan archaeologists have accumulated significant factual evidence, which require discussion of a number of issues related to the initial stages of the early urban culture. The main sources of this article are large settlements of the early urban type, with defensive walls, public and residential buildings, citadels, artisans’ quarters, etc. These sites are located mainly in Nakhchivan and Karabakh. The chronological framework covers the Early (late 4th to 3rd millennia BC) and Middle (first half of the 2nd millennium BC) Bronze Age, Late Bronze, and Early Iron Age (14th– 8th centuries BC), although the origins of settlements of the early urban type go back to the Late Chalcolithic.

Problem of proto-urban traces

Various studies have established that the emergence of proto-towns was associated with the formation of the earliest states in the subtropical zone. Precisely early urban settlements were the centers where the first class societies emerged. Factual evidence makes it possible to identify various features of the proto-urban civilization. For example, according to V.M. Masson, a necessary condition for the emergence of ancient towns was the availability of primitive “money” in circulation, used in exchange and trade operations (1976: 77–85). Masson also wrote that “in essence, the emergence of the first towns meant the emergence of civilization. Therefore, the most general definition of civilization is its definition as a culture of literate citizens” (Masson, 2004: 6–7).

An important indicator of early towns is the presence of defensive structures. In Azerbaijan, defensive walls have been found around the Chalcolithic settlement of Geitepe (Tovuzsky District) (Quliyev, Nishiyaki, 2013).

Similar fortifications, only much more powerful, appear at the sites of the Early Bronze Age in Garakepektepe (Fizulinsky District) (Ismailzade, 2008: 23–25), Daire (Qobustan) (Muradova, 1979: 12–15), and Yanygtepe (near Lake Urmia, Southern Azerbaijan) (Kushnareva, Chubinishvili, 1970: 92).

However, the problem is whether the fortified settlements can be identified as proto-towns. There are several opinions about this. It is believed that settlements with a population of under a hundred persons can be considered as seasonal camps and small villages, settlements with over a thousand population (up to 5000 maximum) as fortified settlements or seeds of proto-towns. The signs of a proto-town are the presence of a citadel, temples, and to a certain extent, the development of artisanal production (Masson, 1976: 141). According to V.G. Childe, a settlement with a population of 5000 or more could have had town status at its early stage (1950). The ancient settlements of this type include Kara-Tepe in Turkey, Altyn-Depe and Namazga-Depe in Turkmenistan, etc. According to J. Mellaart, they can be considered as manifestations of the early stages of proto-towns (1960). This point of view was repeatedly expressed by Masson (1967; 1976: 66–148; 2004). The issues of early urban culture have been analyzed in the works of such Azerbaijan scholars as V.H. Aliyev (1991: 23–56), I.A. Babaev (1990: 29– 61), H.F. Jafarov (2000: 47–71; 2020: 92–101, 130–136), V.G. Kerimov (2007: 85–100), and V. Bakhshaliev and S. Ashurov (Bakhshaliev, Ashurov, Marro, 2009; Ashurov, 2005). In our opinion, there are sites in Azerbaijan which correspond to some of the above criteria.

Settlements of the proto-urban type in Azerbaijan

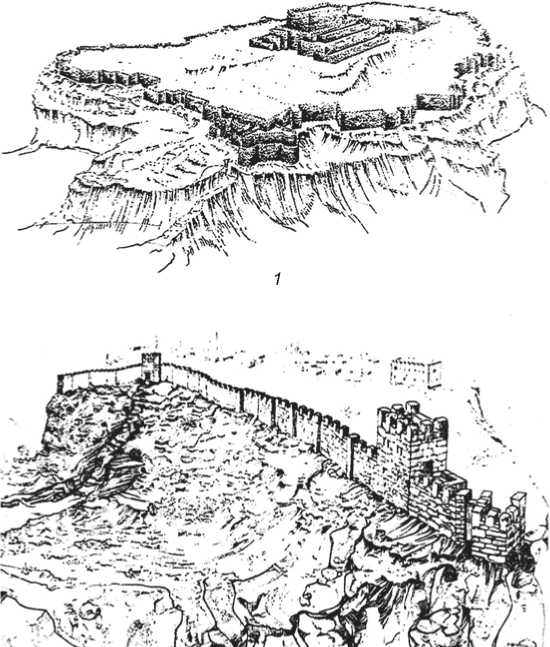

The available evidence makes it possible to include Azerbaijan in the list of regions with early urban culture. This is confirmed by the presence of some settlements that differ from others in many respects, including the Bronze Age sites of Garakepektepe (Karabakh, Fizulinsky District), Ovchulartepe (Nakhchivan), Yanygtepe (near Lake Urmia, Southern Azerbaijan), Kultepe II, Oglangala (Nakhchivan), Uzerliktepe, and Chinartepe (Karabakh, Agdam), as well as Garatepe and Misir-Gishlagy (Karabakh, Agdam). V.H. Aliyev was the first Azerbaijani archaeologist who focused on that problem. He made a suggestion about the emergence of the protourban culture in this region based on the evidence from the Middle Bronze Age sites of Kultepe II and Oglangala, where defensive wall, artisans’ district, public buildings, etc. were discovered (Aliyev V.H., 1991: 25–39) (Fig. 1, 1 ). The sites with the main features of the initial stage of early urban civilization include Garakepektepe

Fig. 1 . Drawing reconstructions of the Oglangala ( 1 ) and Chalkhangala ( 2 ) fortresses of the 2nd to 1st millennia BC (by V.G. Kerimov and D.A. Akhundov, respectively).

in Karabakh (Ismailzade, 2008: 23–25), Yanygtepe in Southern Azerbaijan (Kushnareva, Chubinishvili, 1970: 89–92), and the Early Bronze Age settlement of Daire in Qobustan (Muradova, 1979: 12–15).

Studies have established that social and economic and social and political changes were reflected in the choice of permanent residence, as well as the planning and construction of buildings and defensive wall around the settlement. The separation of cattle-breeding from agriculture, development of artisanal production, emergence of leaders of tribal unions, and the formation and expansion of ties and exchange are some of the indicators pointing to intensification of the early urban culture and to the process of transition to early class society. The development of the main industries of the economy, advances in metallurgy and metalworking, general intensive nature of craftsmanship, and finally, its separation from agriculture should be considered as additional features of transition.

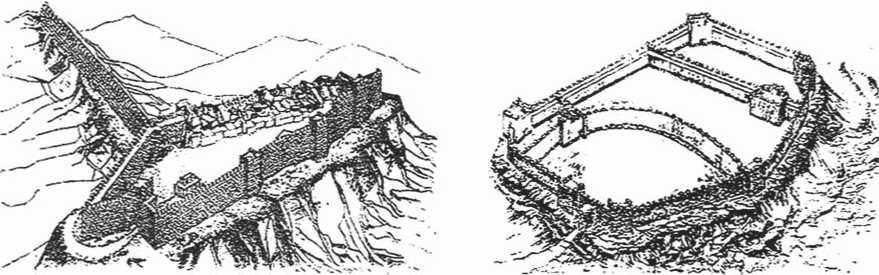

This process can be traced using the example of the settlement of Kultepe II. Its total area originally reached 10 hectares, but only a part of about 3 hectares has been well preserved (Aliyev V.H., 1991: 25–26). On the basis of the study of building horizons and archaeological evidence, V.H. Aliyev identified four stages in the functioning of Kultepe II: first stage in the 20th–19th centuries BC, second stage in the 18th–17th centuries BC, third stage in the 17th–16th centuries BC, and fourth stage (transitional from the Middle to Late Bronze Age) in the 15th–14th centuries BC (Ibid.: 38). The settlement had a bipartite structure and consisted of a citadel and the territory outside of it, where the main population lived. The citadel was surrounded by powerful fortress walls reinforced with rectangular towers and buttresses (Fig. 2, 4). Judging by the layout, the remains of public buildings, residential premises, and artisans’ districts, as well as archaeological finds, V.H. Aliyev believed that Kultepe II was a settlement of the early urban type (Ibid.). Such a structure could reflect complex processes in the emergence of several social groups: noble, wealthy families mostly lived in the citadel, while people engaged in production lived outside of it.

The Uzerliktepe settlement of the Middle Bronze Age in the Southern Caucasus is very important for studying the origins of early towns. This site was investigated by the joint archaeological expedition from the Institute of Archaeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences and the Institute of History of the AzSSR Academy of Sciences in 1954–1956 (Kushnareva, 1957, 1959b; Iessen, 1965: 18–19). The settlement, with an area of about 4 hectares, was built on a natural hill 3.5 m high. In the second cultural layer, numerous houses, utility buildings, pottery and foundry workshops, and a powerful defensive structure encircling the settlement were discovered, as well as remains of two more wide walls outside of that structure (Fig. 2, 1, 2).

The results of archaeological research at Kultepe II, Uzerliktepe, and other Middle Bronze Age sites reveal many aspects of a new stage in the development of the early urban culture. These data prove that starting from the Late Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age, there were important changes caused by the development of productive forces and production relations in many areas of life for the population that lived in the territory of Azerbaijan. These innovations included the emergence of early urban culture.

Analysis of the sites according to their external features and location helps to identify some of their distinctive aspects. For example, according to the classification of fortified settlements by the layout of their defensive systems, most of the sites under consideration

Fig. 2 . Drawing reconstructions of fortresses of the 2nd to 1st millennia BC.

1 , 2 – Uzerliktepe (V.G. Kerimov); 3 – Vaikhyr (D.A. Akhundov); 4 – Kultepe II (D.A. Akhundov).

were of the cape type (Kultepe II, Garatepe, etc.). Usually, they were located on small promontories jutting into the river’s floodplain. However, some settlements belong to the so-called insular type, such as Garakepektepe, Uzerliktepe (Kerimov, 2007: 98–100), and the recently discovered Chinartepe and Misir-Gishlagy.

Rich burials as indicators of social differentiation and transition to class society

Social and property differentiation, which took place from the Early Bronze Age (late 4th to 3rd millennia BC) and gradually intensified in the Middle Bronze Age (second half of the 2nd millennium BC), reached its peak in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (14th– 8th centuries BC). The development of productive forces during that period acquired a wide scale. New fields of craftsmanship emerged; metallurgy and metalworking developed; skills of producing weaponry improved; a layer of merchants acting as a link between artisans and consumers was formed.

Fundamental changes occurring in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages over a relatively short period overshadowed the results of a gradual process of development. The emergence and strengthening of large, powerful tribal unions uniting several tribes led to the need to concentrate the power in the hands of one person. These “kings” controlled vast territories; they were autocratic rulers of large ethnic and cultural associations. In order to confirm that assumption, we need to analyze the burial sites on the territory of Azerbaijan in addition to the settlements. Unfortunately, to date, it has not been possible to synchronize these: in some cases, burial mounds located in the influence zone of the settlements have not been excavated, while in other cases, settlements near the “elite” burial mounds (Borsunlu, Beyimsarov, Sarychoban, etc.) have not been investigated. Nevertheless, using the evidence from these burial mounds, we can obtain the required information for reconstructing ethnic and cultural processes in the period under discussion.

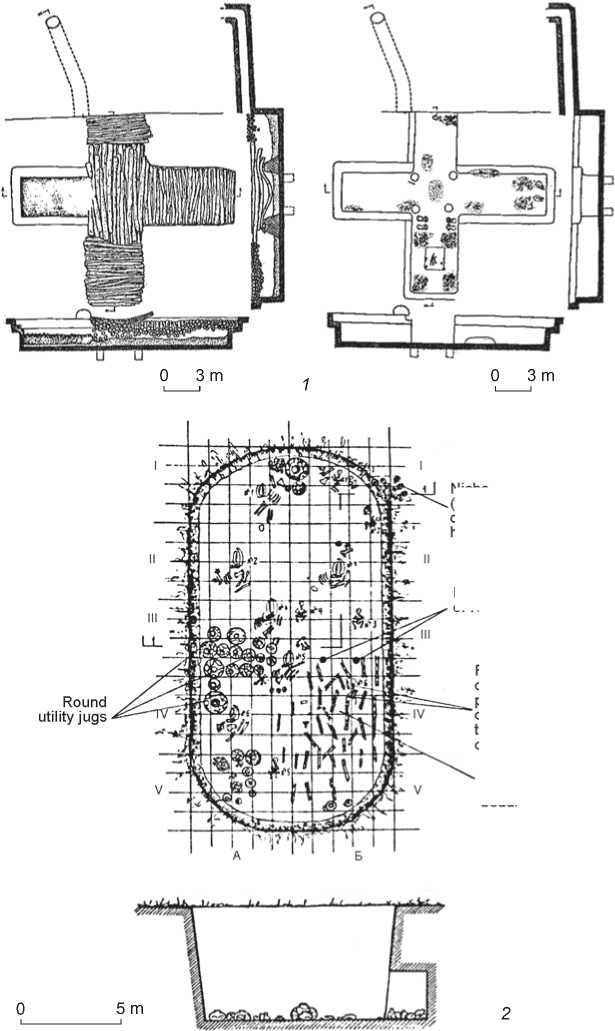

Burial sites of Karabakh, explored in the 1980s, are monumental structures. These include the Borsunlu burial mounds of the 14th–13th centuries BC, Sarychoban of the 12th–11th centuries BC, and Beyimsarov of the 10th– 9th centuries BC (Fig. 3).

Near the village of Borsunlu, in the Tertersky District of Azerbaijan, three burial mounds are located.

Remains of a poorly preserved skeleton of a man -the burial of a captured leader

Remains of a wooden bedding

Niche (width 5.0 m, depth 1.0 m. height 2.5 m)

Fig. 3 . Ground plans and cross-sections of the elite burial mounds of Sarychoban ( 1 ) and Beyimsarov ( 2 ).

Remains of round logs

A giant burial chamber with a total area of 256 m2 was found under the earthen embankment in one of the kurgans, which was 80 m in diameter and 7 m in height. The chamber was covered with more than two hundred pine and spruce logs in two, three, or four layers. The logs of each subsequent layer closed the gap between the logs of the previous layer. Matting made of reeds and tree branches has survived between the layers of logs. The grave was plundered in the ancient times.

The “king” was buried in a tomb of sophisticated structure on a platform bed, surrounded by nine sacrificed people. Burials of horses with bridles and other items of horse harness, bones of cattle, and numerous objects of material culture were found in the burial (Jafarov, 2000: 102–108; 2020: 196–209).

Another burial of an ancient ruler was found under the mound of the kurgan in the village of Beyimsarov, in Tertersky District of Azerbaijan (Jafarov, 2000: 109–114; 2020: 210– 220). The burial chamber, with a total area of 200 m2, was covered with long trunks of coniferous trees. In contrast to the Borsunlu royal grave, the walls of that burial structure were faced with longitudinally sawn logs covered with layers of reeds. Although the burial was destroyed and plundered in ancient times, the remaining objects of material culture have made it possible to reconstruct the original order and funeral rite. The “king” was buried in the center of the burial hall, on a special “throne bed” inlaid with bronze plates. He was accompanied to the afterlife by five sacrificed people. Six horses with items of horse harness were buried in the eastern part of the grave.

The Sarychoban kurgan in the Agdamsky District of Azerbaijan is also of interest. The ground plan of its burial chamber is a regular cross oriented to the cardinal points. Similarly to Borsunlu, the chamber was covered with large logs in several layers. The burial bed of the “king” in the form of a “throne bed” was located in the center of the tomb. The complex was plundered in the ancient times. Burials of sixteen horses with bridles and a large number of sundry items were found there (Jafarov, 2000: 112–114; 2020: 220–233).

The huge sizes of the investigated burial mounds in Karabakh are not accidental. This fact should be viewed in the context of fundamental changes in the life of society. At the time of the transition to class society, local “kings”, who controlled a vast territory, used all available means to build grandiose sophisticated tombs. Rich burials have also been found in other complexes of Azerbaijan, including Dovshanly-Ballygaya, Khojaly, Qarabulaq, Gyanjachai, Mingachevir, etc.

Fortified settlements of the Late Bronze Age as proto-towns

Undoubtedly, the leaders lived in the fortified settlements surrounded by powerful defensive walls. Such settlements of the Late Bronze Age differed from the previous periods in their larger areas, more sophisticated internal structure, presence of protective structures, public, residential, and religious buildings, artisans’ quarters, a square, premises for soldiers and cavalry, etc. Most of these features are present at the Garatepe site (Agdamsky District, Azerbaijan). The total area of the settlement is over 5 hectares. The foundations of a defensive wall reaching 4 m in width have been found along the entire perimeter. It was additionally reinforced with square-shaped corner towers. Garatepe has been dated to the 12th–11th centuries BC (Jafarov, 2000: 67–69; 2020: 130–134). Similar settlements of the early urban type include Misir-Gyshlagi (Agdamsky District, Azerbaijan) with an area of about 3.5 hectares and well-preserved defensive wall. The site belongs to the same period as the settlement of Garatepe (Jafarov, 2000: 69–70; 2020: 134–135).

An example of a sophisticated structure near the Khojaly necropolis is important for describing early town planning in the Bronze Age, in particular the architecture of Karabakh. This structure was first reported in the 1920s by I.I. Meshchaninov (1926). Subsequently, it was mentioned in the work of K.K. Kushnareva (1959a: 372–376, fig. 6). Many details were clarified by H.F. Jafarov (1997; 2000: 131–133; 2020: 160–161) and D.H. Jafarova (2008: 131–134). The “labyrinth” is an oblong building over an area of 9 hectares. The wall, 1–2 m high, was built of stone blocks; gaps between these were filled with small stones. There was a “microcomplex”, which united buildings of various types inside the “labyrinth” and the remains of elongated elliptical walls in the central part of the “labyrinth.” A 40–45 m long access road-corridor 6 m wide was added to this complex from the southwest. It is interesting that the remains of various buildings were also found outside the “labyrinth”.

Judging by the size, structure, ground plan, construction equipment, and other factors, scholars believe that the “labyrinth” was built to protect the population during warfare (Jafarov, 1997) or for permanent residence (Jafarova, 2008: 133–134). This huge complex, located in the necropolis area, apparently performed an applied function. All conditions for long-term defense of a large number of people during enemy attacks were created there, including large area, thick wall, long corridor, and labyrinth, which could mislead the enemy, etc.

Various construction techniques, skilled craftsmen, human resources and leaders, as well as military and executive authorities, were needed to build such a sophisticated and large complex. In some respects, the

Khojaly “labyrinth” resembles cyclopean structures widespread in the mountainous zone of the Southern Caucasus, including Azerbaijan (see Fig. 1, 2). Scholars have proposed different hypotheses regarding the purpose of these structures (Meshchaninov, 1932: 14–68; Jafarzade, 1938: 22–50; Abilova, 1953; Xelilov, 1959: 21–44; Kesamanly, 1999: 30–41; Aliyev T.R., 1993: 34–93; Kerimov, 2007: 85–100). On the basis of analysis of the evidence, we are inclined to believe that some of the structures (including the fortresses of Oglangala, Chalkhangala (see Fig. 1) in Nakhchivan, Lashkyar in Gadabay, and the Khojaly “labyrinth”) were the prototypes of fortified settlements of the early urban type. All these facts are further evidence of the development of early fortification in the territory of Azerbaijan.

The idea of a connection between the settlements of the early urban type and the “elite” burials of the Southern Caucasus is suggested for the first time. The hypothesis that the members of the “elite” of society, who had a high position among the inhabitants of the early urban settlements, were buried in the huge burial mounds, seems logical. Regarding the association of the “elite” kurgans with any of the settlement sites, such as Karakepektepe, Kultepe II, Uzerliktepe, Garatepe, etc., note that burial mounds where the ruling elite of the time could have been buried are located next to these fortified settlements. We hope that further archaeological research will provide additional evidence to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusions

Thus, archaeological evidence confirms that there were significant changes in the life of the population of the entire Southern Caucasus starting from the Final Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age. In the subsequent Middle and especially Late Bronze Age, these changes encompassed social and economic, social and political, and cultural aspects. In the Early Bronze Age, the first large social division of labor occurred, and cattle breeders separated from agriculturalists. In the Middle Bronze Age, artisanal production became a separate industry. In the Late Bronze Age, merchants who linked producers and consumers emerged from the artisans. The presence of defensive walls in the settlements of Garakepektepe (Ismailzade, 2008: 23–25), Daire (Qobustan) (Muradova, 1979: 12–15), Goitepe and Yanygtepe (Southern Azerbaijan) (Kushnareva, Chubinishvili, 1970: 92) is remarkable in terms of the origins of early fortification in Azerbaijan. Such structures reached significant development in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, as evidenced by the well-known sites of Kultepe II, Galajig, Oglangala, Uzerliktepe, Chinartepe, and Garatepe (Aliyev V.H., 1991: 25–28; Kushnareva, 1959b; 1965; Jafarov, 2020:

99–101, 130–134). Such settlements might have laid the basis for the early urban culture on the territory of Azerbaijan.

The emergence of early urban settlements in the region under study became possible as a result of the formation of large tribal unions, which united several tribes. These tribes, which lived in the peripheral zone, were later absorbed by stronger tribal alliances. Towns of the ancient period originated and strengthened in the following centuries on the basis of the early urban settlements. Notably, the ancient state of Caucasian Albania emerged in Northern Azerbaijan, including the zone of foothill and lowland Karabakh, where, according to ancient written sources, many towns were located (Babaev, 1990: 11–17, 51–52).

The rich burial mounds of Karabakh are an important source for studying the emergence of early urban civilization, the disintegration of the primitive communal system, and the transition to class society. Huge burial chambers reminiscent of burial structures of the ancient Eastern rulers, a sophisticated and original burial rite, a large number of accompanying artifacts, human sacrifices, etc. clearly distinguish these monuments from the rest of the sites in the region. Burial complexes such as Borsunlu, Beyimsarov, and Sarychoban reflect the stage of the ancient society when the foundations of the primitive communal system were significantly undermined, and the main elements of class society were emerging. Factual evidence proves that at this stage, all prerequisites for transition to class society existed in Northern Azerbaijan. The processes that began in the Early Bronze Age were developed intensely in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, and reached their peak in the period of the so-called military democracy.

Список литературы The emergence and formation of a proto-urban civilization in Azerbaijan: certain issues in the transition to class society

- Abilova G.A. 1953 Megaliticheskiye sooruzheniya Zakavkazya: Cand. Sc. (History) Dissertation. Baku.

- Adams R. McC. 1966 The Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Chicago: Aldine Press.

- Adams R. McC., Nissen H.J. 1972 The Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Aliyev T.R. 1993 Tsiklopicheskiye sooruzheniya na territorii Azerbaidzhana. Baku: Elm.

- Aliyev V.H. 1991 Kultura epokhi sredney bronzy Azerbaidzhana. Baku: Elm.

- Aliyev V.H. 1992 Azerbaycanda qedim sheherlerin meydana gelmesi. In Azerbaycanda arxeologiya ve etnoqrafiya elminin son neticelerine hesr olunmush elm konfransın materialları. Baku: Baki Dovlet Universitetinin neshri, pp. 24-28.

- Ashurov S.G. 2005 An introduction to Bronze Age sites in the Šarur Plain. Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran und Turan, Bd. 37: 92-99.

- Babaev I.A. 1990 Goroda Kavkazskoy Albanii. Baku: Elm.

- Bakhshaliev V., Ashurov S., Marro K. 2009 Arkheologicheskiye raboty na poselenii Ovchular Tepesi (2006-2008 gg.): Perviye rezultaty i noviye perspektivy. In Azerbaidzhan - strana, svyazuyushchaya vostok s zapadom: Obmen znaniyami i tekhnologiyami v period “pervoy globalizatsii” VII-IV tys. do n.e.: Materialy Mezhdunar. simp. Baku: pp. 59-63.

- Brentjes B. 1976 Ot Shanidara do Akkada. Moscow: Nauka.

- Childe V.G. 1950 The urban revolution. The Town Planning Review, vol. 21 (1): 3-17.

- Iessen A.A. 1965 Iz istoricheskogo proshlogo Milsko-Karabakhskoy stepi. In Trudy Azerbaidzhanskoy arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii, vol. 2: 1956-1960 gg. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 10-36. (MIA; iss. 125).

- Ismailzade G. 2008 Azerbaidzhan v sisteme rannebronzovoy kulturnoy obshchnosti Kavkaza. Baku: Nafta-press.

- Jafarov H.F. 1997 Arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya v Khodzhalakh v 1984 g. Tarix və onun problemləri, No. 1: 153-162.

- Jafarov H.F. 2000 Azerbaycan eradan evvel IV minilliyin akhiri - I minilliyin evvellerinde (Qarabaghın Qarqarchay və Tartarchay hovzelerinin materiallari esasinda). Baku: Elm.

- Jafarov H.F. 2020 Qedim Qarabakh. Baku: Elm.

- Jafarova D.H. 2008 Oruzhiye plemen Karabakha v epokhu pozdney bronzy i rannego zheleza. Baku: Khazar.

- Jafarzade I.M. 1938 Tsiklopicheskiye sooruzheniya Azerbaidzhana. Trudy Azerbaidzhanskogo filiala AN SSSR, vol. 55: 5-54.

- Kerimov V.G. 2007 Istoriya razvitiya oboronitelnogo zodchestva Azerbaidzhana (s drevneishikh vremen do XIX veka). Baku: Elm.

- Kesamanly G.P. 1999 Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki epokhi bronzy i rannego zheleza Dashkesanskogo rayona. Baku: Agridag.

- Kushnareva K.K. 1957 Raskopki na kholme Uzerlik-tepe okolo Agdama (iz rabot azerbaidzhanskoy ekspeditsii 1954 g.). KSIIMK, iss. 69: 129-135.

- Kushnareva K.K. 1959a Arkheologicheskiye raboty 1954 g. v okrestnostyakh seleniya Khodzhaly. In Trudy Azerbaidzhanskoy (Oren-Kalinskoy) arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii, vol. 1: 1953-1955 gg. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 370-387. (MIA; iss. 67).

- Kushnareva K.K. 1959b Poseleniye epokhi bronzy na kholme Uzerlik-tepe okolo Agdama. In Trudy Azerbaidzhanskoy (Oren-Kalinskoy) arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii, vol. 1: 1953-1955 gg. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 388-430. (MIA; iss. 67).

- Kushnareva K.K. 1965 Noviye danniye o poselenii Uzerlik-tepe okolo Agdama. In Trudy Azerbaidzhanskoy arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii, vol. 2: 1956-1960 gg. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 74-102. (MIA; iss. 125).

- Kushnareva K.K., Chubinishvili T.N. 1970 Drevniye kultury Yuzhnogo Kavkaza. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Masson V.M. 1967 Protogorodskaya tsivilizatsiya yuga Sredney Azii. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 3: 165-190.

- Masson V.M. 1976 Ekonomika i sotsialniy stroy drevnikh obshchestv (v svete dannykh arkheologii). Leningrad: Nauka.

- Masson V.M. 2004 Perspektivy metodologicheskikh razrabotok v istoricheskoy nauke (formatsii, tsivilizatsii, kulturnoye naslediye): Otkrytaya lektsiya, prochitannaya v Luganskom natsionalnom pedagogicheskom universitete. St. Petersburg: Akadem-Print.

- Mellaart J. 1960 Excavations at Hacılar: Third preliminary report. Anatolian Studies, vol. 10: 83-104.

- Meshchaninov I.I. 1926 Kratkiye svedeniya o rabotakh arkheologicheskoy ekspeditsii v Nagorniy Karabakh i Nakhichevanskiy kray, snaryazhennoy v 1926 g. Obshchestvom izucheniya Azerbaidzhana. Soobshcheniya GAIMK, No. 1: 217-240.

- Meshchaninov I.I. 1932 Tsiklopicheskiye sooruzheniya Zakavkazya. Leningrad: Pechatniy dvor. (Izv. GAIMK; vol. XIII, iss. 4-7).

- Muradova F.İ. 1979 Qobustan tunj devrinde. Baku: Elm.

- Quliyev F., Nishiyaki Y. 2013 Geytepe ve Hacellemhanlı yashayısh yerlərinde arheoloji tedqiqatlar. In Azerbeycanda Arxeoloji Tedqiqatlar (2012). Baku: Arxeologiya ve Etnografiya Institutu, pp. 309-327.

- Reder D.R., Cherkasova E.A. 1979 Istoriya drevnego mira, pt. I. Moscow: Prosveshcheniye.

- Xelilov J.A. 1959 Qerbi Azerbeyjanın tunj ve demir devrinin evvellerine aid archeoloji abideleri. Baku: Azerbeyjan SSR Elmler Akademiyasi Neshriyyeti.