The ethnoarchaeology of Russians in the Syro-Palestinian region (18th-19th centuries)

Автор: Belyaev L.A., Tchekhanovets Y.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145497

IDR: 145145497 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.2.097-105

Текст обзорной статьи The ethnoarchaeology of Russians in the Syro-Palestinian region (18th-19th centuries)

Introduction:The archaeology of temporal presence

The study of interaction between different cultures has a separate field that is not always taken into consideration while analyzing cross-cultural relations on the basis of archaeological evidence. This field is the archaeology of presence during traveling for scientific-geographical purposes or pilgrimages to a foreign territory. Traces of such presence are manifested in the best way when atypical artifacts of the local culture are found during excavations, or indirectly by the distribution of special pilgrimage items and specific iconographies associated with a particular holy object (a typical example is pilgrims’ badges of the Late Middle Ages in Europe; see the well-known catalog (Spencer, 1998)

and database of the Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen ). Examples of purposeful structuring of the local environment in response to mass pilgrimages are well known and include the development of certain production areas (the industry of “souvenirs” and eulogia—simple and mass-produced or very sophisticated, such as the Bethlehem models of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre of the 17th–18th centuries), accumulation of food and facilities for everyday amenities, as well as creation of spatial infrastructural objects (roads, architectural structures, like shelters, hostels, etc.) or transformation of previously existing types of buildings (a well-known example is the emergence of the subtype of “pilgrimage churches” in the Roman and Gothic architecture of Europe). Finally, travelers and pilgrims who died in a foreign land left burials decorated atypically in terms of the local cemeteries (for example, the Christian cemetery of Galata (Düll, 1989; Düll, Luttrell, Keen, 1991)).

In fact, pilgrimages and tourist-type journeys constitute a form of assimilation or colonization, often being followed by the emergence of settlements of foreigners, such as foreign quarters in Moscow in the 17th century, Galata in Istanbul, and the Russian Compound in Jerusalem, which make a strong impact on local culture. This is one of the important forms of exchange also observed using archaeological methods (for pilgrimages as a phenomenon, see (Sumption, 2002; Pilgrimage…, 1995, Reframing Pilgrimage…, 2005)). This article intends to indicate the opportunities for the development of archaeology of the Russian presence in the Holy Land and discuss the first steps in this direction.

Russian Palestine:Ethnoarchaeological version

First of all, we should mention a partly archaic (given the archaic nature of the phenomenon of mass pilgrimage to holy places) and partly extremely modern (if not futuristic) nature of the Russian movement to Palestine. The emergence of ideas about the lands on which the Biblical and Gospel events took place was an extremely important process in the history of Russia, which did not completely coincide with similar mental developments among the Christian people of the West. The interest of Russian literary men (broadly including both writers and readers) in the Holy Land was extremely strong, which for a long time was expressed not so much in the development of a real movement, but in their love for pilgrim literature, both Slavonic and translated. These were “journeys” and other forms of describing the sacred geography and topography. In fact, the inhabitants of Muscovite Rus (peasants, town dwellers, and service people) knew Palestine (or at the very least its anagogical image) much better than the general geography of their own state and surrounding lands (Fedorova, 2014: 62–71, 165–193).

In the 18th century, the lands of the Ottoman Empire became more accessible for the visits of Europeans. After the reforms of Peter I, the mobility of the inhabitants of the Russian Empire also somewhat increased. Visits to the Holy Land became more frequent, which gave rise to a new wave of “journeys” ( khozhdeniya ), which gradually turned into travel notes, diaries, and other forms of travel descriptions, both scholarly and literary. Medieval attraction to holy places, typical curiosity of the European Orientalism, and political necessity gave rise to the phenomenon called “the Russian Palestine”, combining mental and practical advancement in the Syro-Palestinian region into a single concept (for the main milestones in the development of this process, see (Velikiy knyaz…, 2011)). For about half a century (the 1860s–1910s), the pilgrims’ movement from Russia became large-scale. This alone paved the way for a powerful cultural interaction.

The support of the movement on the part of the society and state, which partly formed it and tried to use it as a tool in foreign policy, gave it a systemically structured centralized structure, so stable that it was possible to keep it from final disintegration, albeit with significant losses, for about a century (not without reason the main actors were not only the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but also the Russian Spiritual Mission, as well as a special public organization or in fact also a state organization called the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society; for more details, see (Rossiya…, 2000)). Until recently, traces of the interaction could be seen in the everyday life of Arab villages and towns: Russian samovars were widely used there; silver coins of the last Russian Tsars were a part of necklaces and bracelets, and porcelain made in Russian factories was on tables. All this can be also found to the present day, but mainly as items of antique trade. The Russian contribution of the 19th to early 20th centuries survived in the form of textbooks. Graphic art in journals of the time, which to a certain extent was still used by reporters instead of early photography, also shows Russian presence at the time (Fig. 1). Yet the general situation is different today: in the Arab settlements, the pre-revolutionary Russians are remembered mainly from the stories of grandmothers and great-grandmothers, while the Russian infrastructure has turned from a true working mechanism into a more or less well-preserved heritage. Many elements have been forgotten to such an extent that it is possible to bring back the memories of their existence only with the help of archaeology (Belyaev, 2019).

Although the Israeli law does not recognize evidence that appeared later than 1700 as archaeological records (the Antiquities Law was passed in 1978), the general trend towards making archaeology more recent in the world requires including monuments from the Late Ottoman period, World War I, and even the British Mandate (1917–1948) into archaeological research. Moreover, exactly these sites, as lying above other cultural layers, become subjected to destruction during any excavation works, and should be treated as equivalent to other historical evidence regardless of whether they are the objects of urban or rural archaeology (for examples, see (Arbel, 2014; Ottoman Jaffa…, 2017; Re’em, 2010; Finkielsztejn, Nagar, Bilig, 2009; Re’em, Forestani, 2017; Re’em, 2018b; Tsuk, Bordowicz, Taxel, 2016; Taxel, 2017; Peretz, 2017; Zilberstein, Shatil, 2013)). In the present-day Russian legislation, a 100-year chronological boundary is recognized as the threshold of archaeology, which makes it possible to consider any pre-revolutionary items as archaeological.

An extremely typical example in the field of “archaeology of the Russians” was a find made in 2018 in the area of Jerusalem known as Musrara (north of the walls of the Old City, near the Notre Dame de France complex). After starting works on construction development of a long-abandoned site, the employees of the Israel Antiquities Authority quite expectedly discovered layers of the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods. They were covered by the foundation of a later (not earlier than the 19th century) building with an undoubtedly European layout. It was not easy to identify the structure; prior to the beginning of works, scholars had no information about its existence. Archival research has revealed a three-story building of distinctive architecture on the photographs of the early 20th century. On the map of the period of the British Mandate, it was vaguely named “District Offices”. A detailed plan published in 1895 by C. Schick, the Chief Architect of Jerusalem in the second half of the 19th century, has made it possible to identify the building, designated as “Wohnung der russischen Konsulats beamten”. Thus, the situation became clear: archaeologists accidentally discovered one of the Russian possessions in Jerusalem in the 19th century, also identifying the name used at that time: the Homsi land plot at the New Gate (3436 m2), on which a residential building was built for the employees of the Russian consulate. Previously unpublished documents reflect lengthy official correspondence, the process of registration of the building, and other ordeals in Turkish and Russian offices. The house needed by the officials of the Russian Consulate General was built, but after less than a century it was demolished under unclear circumstances (Tchekhanovets, Vach, 2019; Vach, 2018).

In recent years, during the development of the vast zone in Jerusalem that in the past belonged entirely to the Russian Compound outside the Jaffa Gate—the center of the Russian pilgrimage movement in Ottoman Palestine—

Fig. 1 . Russian pilgrims at a church shop in Jerusalem. Engraving of the late 19th century.

the remains of other buildings of the last third of the 19th century with their infrastructure (cisterns and canals), traces of construction sites (quarries, lime kilns), etc. were also discovered. Similar components of infrastructure at the site of the Russian Compound were discovered by the excavations of 2015–2017 (Tchekhanovets, Arviv, Vach, in press); more limited evidence was found at the Veniaminovsky Compound (Kagan, 2011). Along with archival data, these finds reveal the development of the city and demonstrate the fusion of European and local elements, and obvious cultural interaction.

These examples of the archaeology of the Russian presence are strictly local. They are supplemented by widespread evidence of primarily epigraphic nature: inscriptions of pilgrims, sometimes very special and unique, made in the monumental style, and ordinary graffiti with prayers, which were left by almost every pilgrim. Scholars eagerly search and publish early inscriptions, sometimes making startling discoveries. For example, the first Russian inscriptions in the Holy Land belong to the 12th century; they have been found in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (Artamonov, Gippius, Zaitsev, 2013). Unfortunately, such “spontaneous” epigraphy of the 18th–19th centuries remains almost unstudied, although it is informative in its own way. The experts from the Israel Antiquities Authority have been working on photographing inscriptions both in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and monasteries of the Old City. Extensive collections of photographs have already been compiled, but they have not yet been read (for the first publication, see (Belyaev, Vach, 2019))*.

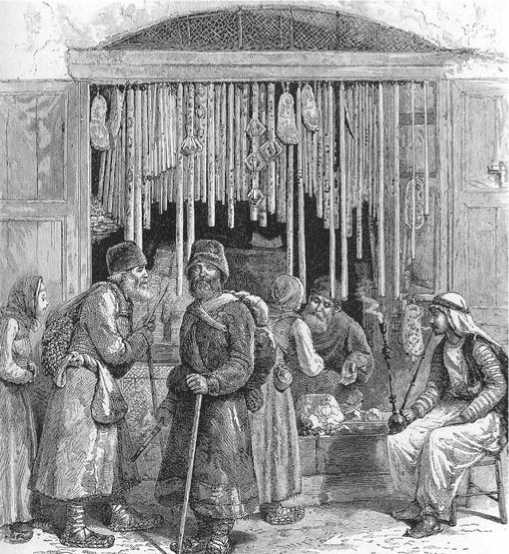

Dozens of Russian and other Slavic, as well as Romanian and Greek inscriptions have been found in the Monastery of the Holy Archangels. For decades, this monastery served as a stopping place for Orthodox groups, a kind of quarantine for the foreigners. The first Russian spiritual mission was located in its cells before the Russian Compound was built outside the Jaffa Gate. These texts serve as an important addition to the little-known “journeys”, since they have the same authors. Monumental forms of epigraphs preserving various visits, which were executed in a quite professional manner and apparently commissioned by the pilgrim, are also of interest. On the contrary, some records look careless, but were made on specially carved fields (the inscriptions of the pilgrims Ivan Birizovsky from Voronezh and Ivan Dorokhov from the Kursk village of Kudenitsyno, 1857) (Ibid.: 96–97) (Fig. 2). Such is the earliest inscription among those found so far, made in 1720. It is located in the monastery in one of the cells, and informs us that “Hieromonks Sylvester and Nicodemus Rikhlovsky from the Chernigov Diocese of Little Russia came here to worship the Sepulchre of the Lord” (Ibid.: 96). Sylvester and Nicodemus, the monks of the Rykhlovsky St. Nicholas Monastery, traveled to Constantinople and Palestine. In 1728, Sylvester (Dikansky) compiled a description of the journey, known in two manuscripts (part of one manuscript was published in 1883, and the complete author’s manuscript is kept in the library of Tomsk State University and is being prepared for publication (Opisaniye…, 1883; Slavyano-russkiye rukopisi…, 2009; Putnik…, 1728)). Until now, it was believed that the journey of the Chernigov monks began in 1722, but in fact this could have been the year of their return.

Outstanding inscriptions outside Jerusalem include culturally important Latin graffito left by Bishop Porphyry (Uspensky), the founder of the Russian Spiritual Mission in Jerusalem, at the important intersection of Sinai (Tchekhanovets, 2018). Along with such sophisticated sources as large buildings, urban infrastructure, and construction sites, large-scale archaeological evidence (in the traditional sense of the word) clearly indicates the Russian presence in Palestine. This evidence was left by the first Russian missionaries at the Russian sites in Jericho, Hebron, and other places (Fig. 3). These include small items of glass, mostly pharmacy vessels used for holy water of the Jordan and other revered water sources or for blessed oil, some also probably originating from

Russian hospitals. Fragments and intact items have been recently found during excavations in the Holy Sepulchre Church (Avni, Seligman, 2003) and in the City of David (excavations in 2018); their subjects and iconography of the Gospel scenes, similar to the eulogia of Byzantine Palestine, demonstrate stability of pilgrimage practices. Fragments of vigil lamps also belong to this group.

It is possible to perceive the already mentioned less specific items, such as household porcelain, details of samovars, and other kitchen appliances, as evidence of the transfer of cultural traditions. These were numerous, for example, in the layers of the Russian possessions in Jericho, and make the distant town of Byzantine and earlier periods a legitimate topic of historical archaeology of both Russia and Palestine. This regards not only the world of things, but also the space of onomastics with the concept of “Moskobiye”, attributed by the local population to any Russian sites, and such a stable concept as “Russian mosaics” (that is, Byzantine mosaics found on Russian land plots (Belyaev, 2016: 47–82)) in the scholarly vocabulary.

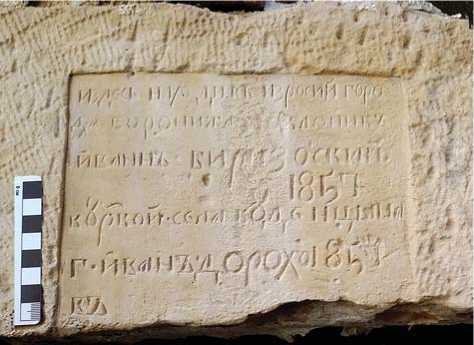

Not all pilgrims and travelers managed to return to their homeland; burials and small Russian cemeteries, clearly representing the first stage in the development of the sites, have become a natural form of manifesting their presence. For instance, such a cemetery of the 1880s, consisting of four graves marked by tombstones is located in the land plot in Jericho, which was bought in 1883 by Athos Hieromonk Joasaph (Ivan Kirillovich Plekhanov) for establishing St. Michael Monastery of the Holy Trinity. All tombstones were marked with a cross, but only two had inscriptions: a Russian woman Elena Ignatyevna Reznichenkova, monastic name Eulampia, August 8, 1885 (Fig. 4, a ), who donated money to buy the plot, was buried under one slab; an unknown woman was buried under the other slab with the inscription “Natalia. 1883. NOEM 6”. The diary of Archimandrite Antonin (Kapustin), the founder of the pilgrims’ hospice in Jericho, tells us the story about the death of a pilgrim with the same name, but who died a year later: Natalia Ivanovna Elungkova, the daughter of an honorary citizen, died at 45 from gangrene on June 21, 1884, after donating 30,000 rubles for the development of Russian sites and other matters of piety.

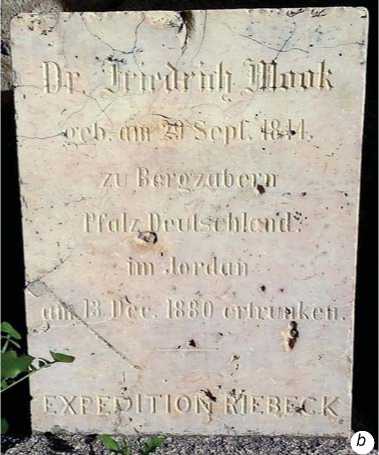

As far as individual burials are concerned, some of them are very exotic. On Antonin’s land plot in Jericho, there was a grave (or at least a tombstone) of the prominent Orientalist traveler and physician Friedrich Mook (September 29, 1844–December 13, 1880), a native of Bad Bergzabern (Palatinate), who drowned in the Jordan during the famous expedition of Emil Riebeck— another German traveler in the East (apparently there was no other piece of Church land to bury a Christian in Jericho). This is an important example of a curious cohesion of Christian Europeans—a nutrient medium for cultural exchange (Fig. 4, b ).

Fig. 2 . Commemorative inscription of Ivan Birizovsky and Ivan Dorokhov. 1857, Jerusalem, courtyard of the Monastery of the Holy Archangels ( photo by the authors ).

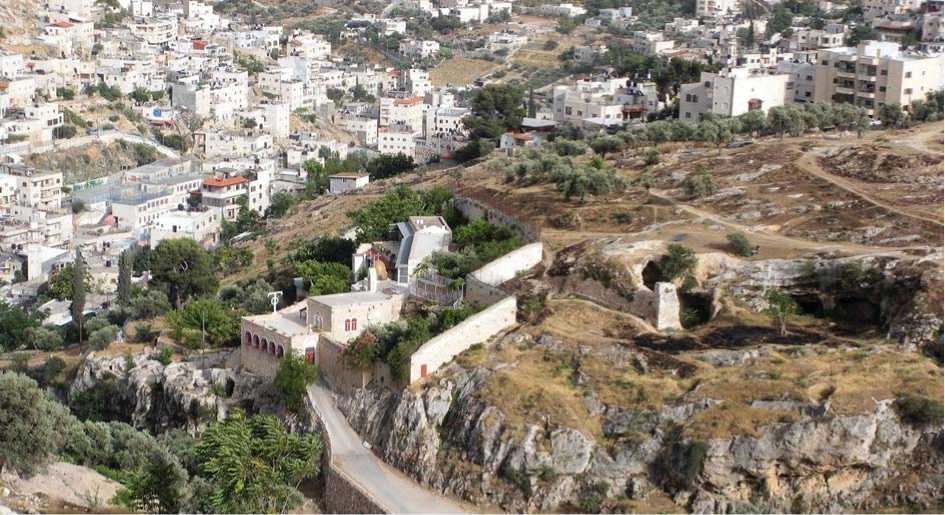

A find from Aceldama of the Gospel narrative (Matthew 27: 6–8) in the southeastern part of the Hinnom Valley (also “Potter’s Field”) is even more surprising. Since the Roman period, this place with burial caves hewn in the slopes has become a part of the system of cemeteries surrounding Jerusalem. In the Byzantine period, it was an abode for hermits, and in the Middle Ages it turned to a place of mass burial of pilgrims (Re’em, 2018a: 153– 154) (Fig. 5). Aceldama was mentioned literally by all

Fig. 3 . Items of the second half of the 19th century from the site of the Russian Museum and Park Complex in Jericho (after (Belyaev, 2016)). a – porcelain and glass; b – metal and ceramics.

people who wrote about Jerusalem, including Hegumen Daniel in 1106–1108 (Zhitiye…, (s.a.)). Its revered soil was exported to Europe by ship (it was assumed that it provided rapid tissue decomposition, but did not cause decay processes) (Bodner, 2015). In the early 14th century, in Aceldama, a large charnel house was built with 15 roof openings for lowering bodies into it; the accumulated bones were subsequently buried in the caves of the Greek monastery of St. Onuphrius the Great (renewed in 1892). The descriptions always emphasized the foreign constituent of buried persons (Khozhdeniye…, (s.a.)). Memorial services and burials were performed there until the 19th century (Tobler, 1854: 274; Conder, 1881: 271; Leonid (Kavelin), 2008: 215). Restoration works in 2002 and 2011 showed the accuracy of the descriptions and made it possible to calculate the capacity of the charnel (almost 13,000 bodies, cf.: (Proskinitariy…, 1889: 181– 183)). Skeletons have not been found at the site, but one of the monastery caves that was filled with secondary burials of bones belonging to hundreds of people, mostly adult

Fig. 4 . Tombstones at the site of the Russian Museum and Park Complex in Jericho.

Fig. 5 . The area of ancient cemeteries of Aceldama in Jerusalem (after (Re’em, Tchekhanovets, 2019)).

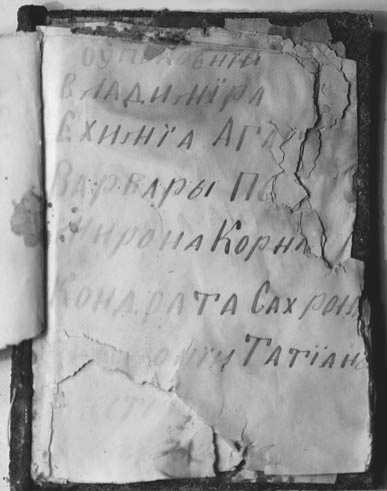

Fig. 6 . Page of the commemoration book of the Russian pilgrim Galushkina, buried in the 1910s in the cemetery of the Monastery of St. Onuphrius the Great (after (Re’em, Tchekhanovets, 2019)).

men, was studied in 2010. A few female remains included a skeleton with scraps of clothing and small book bound with a metal cover—a family commemoration book printed in the Wilde typography in Moscow and belonging to a female pilgrim with the last name of Galushkina (Fig. 6). Her exact origin has not yet been established, although a woman with that last name was mentioned in the diary of Father Antonin (Kapustin) (Re’em, Tchekhanovets, 2019). The owner of commemoration book, Galushkina (or Golushkina) apparently originated from Southern Russia and belonged to a low class (peasant?). As is known, the large scale of pilgrimage was made up of peasants and residents of urban outskirts, from the western borders of the Russian Empire to Siberia (journey to and comprehension of the phenomenon of the Russian Palestine for the Siberians generally became one of the ways of forming their self-identity (Valitov, 2019; Valitov, Kibardina, 2019); this topic is now being studied by a group of scholars from Omsk University under the leadership of M.S. Shapovalov).

Conclusions: All in the future

The question of the Russian presence in Palestine has been actively studied since the last quarter of the 20th century, but never from the perspective of “dialogue of cultures”, which can be detected by nothing other than archaeology of the late period. Even the former Russian sites retain certain connection with Russia in the eyes of the local dwellers and scholars, which is facilitated by the preservation of the majority of buildings built on them in the 19th to early 20th centuries. It is important that the process of Russian development of Palestine on its own created a kind of cultural layer, left material traces, which include types common for archaeology—from household waste to necropolises. From a scholarly point of view, such cultural and anthropological evidence serves as a field for historical and archaeological experiments; it is also important for museum work on Russian sites, such as the Joasaph plot in Jericho, where the Russian Museum and Park Complex was created in 2011.

The Israeli archaeologists, who possess an enormous ancient heritage at their disposal, are also willing to study local Russian antiquities and thus form a separate field as a part of the archaeology of Israel (international by definition). In 2019, a Russian-Israeli seminar was held at the Tel Aviv University (with the participation of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy

0 5 cm of Sciences), focusing on the archaeology of Russian possessions of the 19th to early 20th centuries (“Russian Archaeological Project, 19th–21st centuries”). In addition to this, public lectures have been held and this topic was announced on the ANET resource of the University of Chicago (Tchekhanovets, Belyaev, 2020). A special annual journal on the study of sources has been published since 2010, reflecting deep mutual interest in the heritage of the Holy Land (completely non-confessional, despite its name “Jerusalem Orthodox Seminar”). Undoubtedly, we have the right to speak about the beginning of the emergence of Russian ethnoarchaeology of the Syro-Palestinian region.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project No. 18-09-40075) and Competitiveness Improvement Program of the Tomsk State University.