The final Bronze Age in the Minusinsk basin

Автор: Lazaretov I.P., Poliakov A.V., Lurye V.M., Amzarakov P.B.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Based on the most recent excavation fi ndings, this article discusses a disputable group of burials, previously believed to represent the Bainov stage of the Tagar culture (900–700 BC) in the Minusinsk Basin. Analysis of these burials unambiguously supports I.P. Lazaretov’s idea that they fall into two independent and unrelated groups. One of them continues Late Bronze Age traditions, whereas the other demonstrates new features exclusively associated with the Tagar culture. Most complexes of the Bainov type represent the fi nal stage in the evolution of Late Bronze Age traditions. This is evidenced by various categories of grave goods, features of burial structures, and the funerary rite. These burials can be attributed to stage IV of the Late Bronze Age in the Minusinsk Basin. The second, smaller group reveals entirely new features, typical of the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture. These include novel structural features in kurgan architecture, different female funerary attire, and the custom of placing weapons in graves. This attests to the arrival of a new population group with its own traditions, resulting in the emergence of a Scythian type culture on the Middle Yenisey. These burials should be attributed to the beginning of the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture. Hopefully, future studies will help to separate out a special late group of Bainov burials, contemporaneous with the early Podgornoye kurgans. Currently, it is possible to discern certain features suggesting that this population took part in the origin of the Tagar culture.

Minusinsk Basin, Middle Yenisey, Late Bronze Age, Tagar culture, Bainov stage, Podgornoye stage

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146823

IDR: 145146823 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.1.108-118

Текст научной статьи The final Bronze Age in the Minusinsk basin

Interpreting sites of the transitional period from the Bronze Age to the Early Scythian period in the Minusinsk Basin is an important issue. According to traditional views on the emergence of the Tagar culture, a special (Bainov) group of sites can be distinguished as the earliest stage, which combined both obvious manifestations inherited from the traditions of the Bronze Age and early cultural features of the Scythian period (Teploukhov, 1926: 90, 94; Kiselev, 1937: 166; 1951: 187–188; Gryaznov, 1956:

70; 1968: 188–189; Vadetskaya, 1986: 96–100). Thereby, unconditional continuity between two successive archaeological cultures, the Karasuk and Tagar, has been postulated.

It is true that on the chronological scale of the region, sites of the Bainov type occupy an intermediate position between the Lugavskoye complexes and most complexes from the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture (Poliakov, 2022: 227–312). However, a detailed analysis of these sites has revealed their clear heterogeneity. Some of the complexes, including the eponymous Bainov Ulus burial

site, clearly demonstrate consistent development of local traditions of the Late Bronze Age in funerary rite, kurgan architecture, pottery shapes and decoration, as well as in the main categories and types of bronze items. However, these complexes do not contain anything that could connect them with the sites of the Tagar culture, primarily, elements of the Scythian triad. It has been suggested considering the complexes of this kind as belonging to the final stage IV (Bainov) of the Late Bronze Age (Lazaretov, 2007; Lazaretov, Poliakov, 2008; Poliakov, 2020; 2022: 285–289). On the contrary, another part of the transitional sites manifest fully formed features typical of the Scythian period, with minimal manifestations of the previous period. Such sites should be attributed to the classic Tagar culture as early Podgornoye stage complexes.

Currently, among the sites of the Late Bronze Age, burials of stage IV (Bainov) have been studied the least. The total number of complexes attributed to this stage does not exceed several dozen, which is a result of their scarcity, very short time of existence (second half of the 9th to early 8th century BC), and late identification as an independent group of sites. Ordinary cemeteries of this group consist of no more than five to ten burial structures. Until recently, the largest cemetery of the transitional period was the Byrganov V complex containing 17 burial mounds; some of them showed clear influence of the Tagar culture, and one should be definitely interpreted as an early Podgornoye burial.

The problem of selecting the previously studied complexes and individual burials of the Bainov type as parts of burial grounds of different periods should be especially addressed. Without the necessary detailed analysis, these have often been attributed to the Tagar culture. It has often been observed that the Tagars reused burial mounds of the Late Bronze Age, completely or partially destroying central early burials and making their own burials in their place. Meanwhile, the Bainov enclosure structures, and even children’s graves beyond their eastern walls, were often preserved. However, the evidence from such burial mounds is usually interpreted as being purely Tagar. There are also frequent cases when basically early Podgornoye complexes are unjustifiably attributed to the Bainov stage. Such confusion results from the lack of clear criteria for distinguishing between the sites of the Late Bronze Age and the Scythian period.

In 2020–2022, the Sayan expedition from the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the RAS, together with the “Archaeology, and Historical and Cultural Expertise” Research and Production Center carried out extensive excavations of settlement and burial complexes in the south of the Republic of Khakassia. Three complexes contained burials of the Final Bronze Age (IV, Bainov stage). Thirty burial mounds of the Bainov type were explored only at the burial ground of Ust-Kamyshta-1. Good preservation of burial structures, as well as numerous pottery and bronze implements, make it possible to establish clear features that distinguish this special group of sites. This work should be compared with the previous stage III complexes (Lugavskoye) and early Podgornoye burial mounds located at the same cemetery.

Architecture and grave structures of the burial mounds

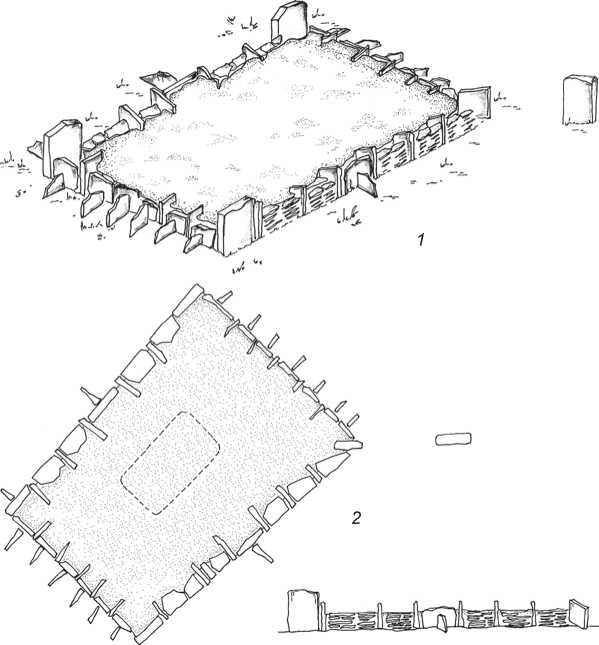

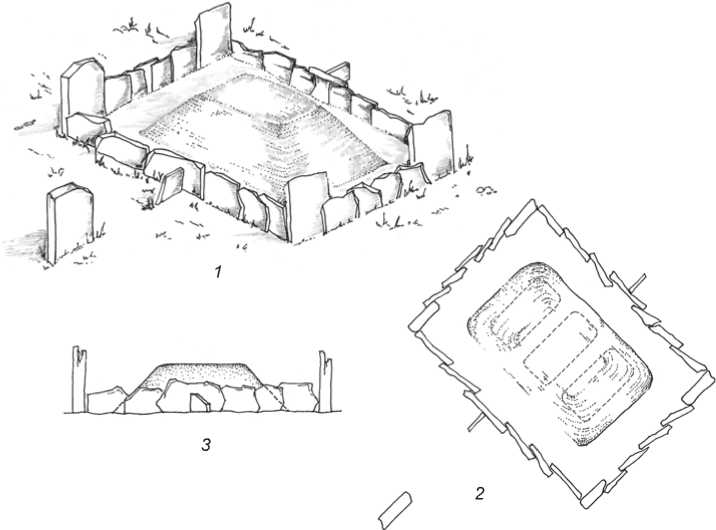

According to their external features, burial mounds belonging to the Bainov stage of the Late Bronze Age are noticeably different from the early complexes of the Tagar culture. They consist of flat platform enclosures, with the entire internal space evenly filled with native soil (Fig. 1, 1 ). Usually, the upper edges of the enclosure

Fig. 1 . Burial mound of the Bainov stage.

1 – reconstruction of the original appearance; 2 – ground plan of a typical burial mound;

3 – reconstructed facade of the enclosure wall.

were carefully made even and almost did not protrude above the surface of the modern steppe (Fig. 2). During large area excavations, numerous pits from which soil was taken for making the mound have been discovered in the space between individual complexes. This tradition originated at the sites of stage III (Lugavskoye) of the

Late Bronze Age and ceased to exist upon the emergence of the Tagar culture.

The enclosures were of square or rectangular shape. The rectangular enclosures usually had their long walls along the SW-NE line, along the axis of the grave (Fig. 3). Quite often, there were trapezoidal structures,

Fig. 2 . Burial mound of the Bainov stage: example of making the height of the enclosure wall even.

Fig. 3 . Enclosure of the burial mound of the Bainov stage (view from the northeast).

with the southwestern wall shorter than northeastern one. The slabs of the enclosure were laid horizontally one on another, with their ends adjacent to each other; vertical slabs were regularly set between them (see Fig. 1, 2 ). In some enclosures, vertical slabs only appeared in the central part of two sides or all four sides, whereas the corners were formed by horizontal stonework (Fig. 4). According to the ground plan, these structures resembled brackets; therefore, such enclosures are referred to as “bracketed”.

A distinctive feature of the Bainov stage structures was the presence of numerous buttresses to protect the burial mound-platform from destruction caused by soil pressure. Corners of the enclosures were often marked by large vertical slabs, which reached a height of 1.5–2.0 m. In the eastern corner, the stone could be set diagonally rather than parallel to the wall, dissecting the corner, and could also be set outside the enclosure at a distance of 1.0–1.5 m east of it (see Fig. 1, 1 , 2 ).

Only one grave was located in the center of the burial mound. Children’s burials, if any, were made beyond the northeastern wall of the enclosure. Most often, graves were shallow soil pits, with traces of low logwork. Wedging of small sandstones or broken stone slabs was sometimes observed between the logwork and pit wall. The flooring consisted of thin logs laid in a longitudinal direction at the level of the ancient daylight surface. They were sometimes lined with sandstone slabs or broken stone.

The deceased were placed in an extended supine position, with their heads directed to the southwest or northeast. It has not yet been possible to detect any regularities in this choice. Typically, there were two vessels, large and small, for each buried person in the grave. The larger vessel was located near the head; the smaller vessel was nearby or could have been set towards the legs. Cutlery in the form of a knife and awl was usually placed on the smaller vessel. The remains of a sacrificial animal, i.e. sheep or cow, were present near the feet of the buried person. It is interesting that traces of red pigment, which might have been used for painting the footwear of the dead, can be clearly seen on the shin bones of the deceased in many burials.

Grave goods

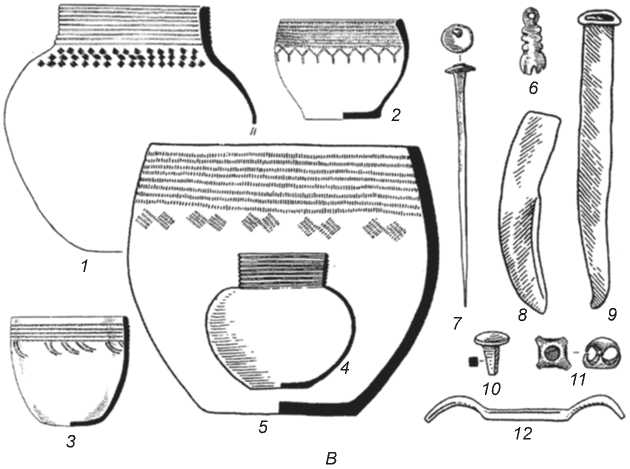

Pottery from the burials of the Bainov stage can be classified into two types: slightly profiled jars with a wide mouth (Fig. 5, 2 , 3 , 5 , 13 – 15 ) and spherical vessels with a high narrow neck (Fig. 5, 1 , 4 , 16 , 17 ). This division emerged already in the complexes of the middle to final period of stage III (Lugavskoye) of the Late Bronze Age and came to its peak at stage IV (Bainov). A number of vessels, especially large jars, show traces of smoothing with a toothed stamp or wood chip on their inner and outer surfaces. Ornamentation was relatively meager and monotonous, with a tendency toward focusing on the upper part of the vessels. It usually combined rows of slanting stamp impressions or notches, thin horizontal lines, or rhombic imprints, sometimes supplemented with a horizontal zigzag, “hanging” triangles, or groups of notches or slanting lines from stamp imprints. The vessels were predominantly decorated with a toothed stamp. Imprints of a smooth ornamenting tool and carved lines were much less common. A typical feature of pottery at

Fig. 4 . Enclosure facade of the burial mound of the Bainov stage (view from the southwest).

0 5 cm 16 0 5 cm

Pottery А Bronze

the Bainov stage was a straight, strictly horizontal cut of the rim. Quite often, there was a small bulge on its inner side (Fig. 5, 14 ), formed during molding, when the vessel was placed on a flat solid surface with its mouth down. In spherical narrow-necked containers the edge could be straight or rounded. The bottom of the vessels at the time of molding was rounded and possibly pointed. During its flattening on a flat horizontal surface, a base typical of Bainov pottery was quite often formed at the bottom part of the vessels (Fig. 5, 2 , 15 , 16 ).

Burials, especially those of females, contained rich and diverse bronze items, such as numerous

Fig. 5 . Grave goods from the burials of the Bainov stage.

A – early chronological horizon; B – late chronological horizon.

Byrganov V: 1 , 6 , 11 – kurgan 9, grave 7; 7 – kurgan 2, grave 2; Lugavskoye III: 2 – kurgan 1; Beloye Ozero I: 3 – kurgan 5, grave 1; 13 – kurgan 63, grave 3; 14 – kurgan 53; 16 – kurgan 40, grave 2; 17 , 19 – kurgan 62, grave 2; Bainov Ulus: 4 – kurgan 1; 8 – kurgan 4; Samokhval: 5 – kurgan 9, grave 2; Ilyinskaya Gora: 9 – kurgan 1; Minusinsk VII: 10 , 12 – kurgan 4, grave 1; Efremkino: 15 – kurgan 8; 20 , 21 – kurgan 7; Ust-Chul: 18 – kurgan 6, grave 3;

Askiz VI: 22 – kurgan 3.

1–5 , 13–17 – pottery; 6–12 , 18–22 – bronze.

temporal rings, clips, and tubular beads, three- and four-lobed pendants, mirrors, rings with biconical signet, and buttons with an eyelet, bridge, or peg with a mushroom-shaped end. Figured plaques with four, six and eight ribs, and triangular plates with punched ornamentation have been found sporadically (Fig. 6). A figurate bone comb with ornamentation of triangles pointing towards each other is of particular interest. In its appearance and decor, it is much closer to similar items from the previous periods than to Late Tagar artifacts. It is especially similar to a comb found in burial 2, kurgan 7 at the Iyus cemetery (Poliakov, 2005: Fig. 1, 13 ). This burial belongs to stage III (Lugavskoye) of the Late Bronze Age.

Because of the almost total looting of burial mounds of the pre-Scythian period, massive bronze items have rarely survived in graves. These could be items of unknown purpose, tetrahedral awls with a mushroomshaped cap, laminar knives, and knives with a ring pommel or half-ring pommel (“arch on a bracket”). However, more common are not complete items, but their bronze blades, which previously were inserted into a wooden haft.

Sites of the Bainov type and complexes of the Late Bronze Age

Comparison of the Bainov complexes with burial mounds of stage III (Lugavskoye) of the Late Bronze Age shows numerous and detailed similarities in almost

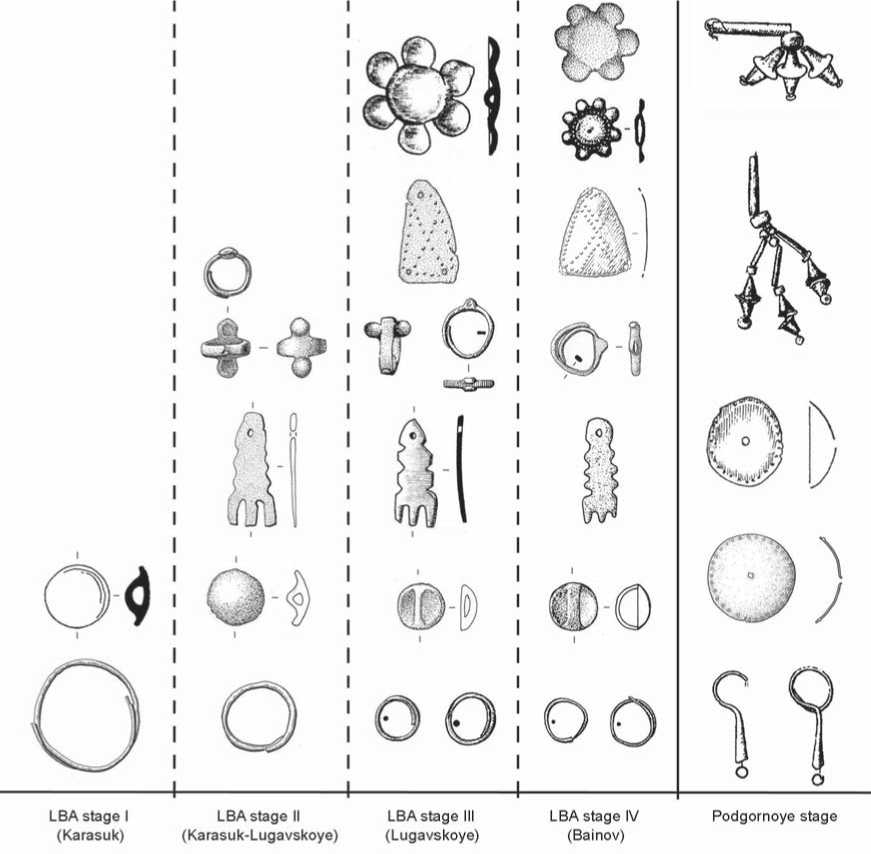

Fig. 6 . Comparative table of female ornaments of the Late Bronze Age (LBA) and of the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture.

all their aspects, including burial structures, funerary rituals, pottery, and bronze items. For example, the Bainov flat burial mound-platforms clearly originated from similar structures of the previous time. Excavations of large areas at the Lugavskoye part of the Ust-Kamyshta-1 cemetery revealed exactly the same pits for soil extraction as those appearing near the Bainov burial mounds. Combinations of horizontal stonework and vertical slabs forming bracketed structures often appeared in both Lugavskoye and Bainov enclosures. Protruding corner stones and sometimes protruding wall stones were widespread. Such features of the Bainov funerary rite as placement of children’s graves beyond the eastern wall of the main enclosure, the supine position of the buried person, presence of two vessels in the burial, and placement of a knife and awl on the small vessel emerged starting in the middle of the Lugavskoye stage. The division of pottery into two main types (slightly profiled jars and spherical vessels with high and narrow necks) took place at the same time. Gradual transition from the Lugavskoye round-bottomed vessels to the Bainov flat-bottomed vessels is clearly noticeable. There are many examples of their combination in the early graves of the Bainov period. The same is true for the ornamental tradition: all elements of Bainov decor, their placement zones and application technique directly followed from Lugavskoye prototypes.

Nearly all main categories and types of grave goods of the previous period occur among the Bainov bronze items. This is primarily true for large scale ornaments, i.e. elements of the female outfit. These have a traditional appearance or are slightly transformed by simplification and miniaturization (Fig. 6). The relatively rare items of the male prestigious complex underwent significant changes. Bronze belt distributors (see Fig. 5, 11, 20), awls with a mushroom-shaped cap (see Fig. 5, 7), laminar knives without a distinctive pommel (see Fig. 5, 8), as well as knives with a ring or half ring pommel (see Fig. 5, 9, 22), appeared in the graves. Ringed and half-ringed knives completely replaced curved Lugavskoye knives with mushroom-shaped pommels.

Thus, recent large-scale studies at the burial grounds of Smirnovka-4, Ust-Kamyshta-1, and Kirba-Stolbovoye-3 have significantly expanded and reinforced the previously suggested links between stage III (Lugavskoye) and stage IV (Bainov) of the Late Bronze Age. There have appeared additional arguments for attributing the sites of the “Bainov Ulus type” to the final Late Bronze Age.

Bainov-type sites and the Tagar culture

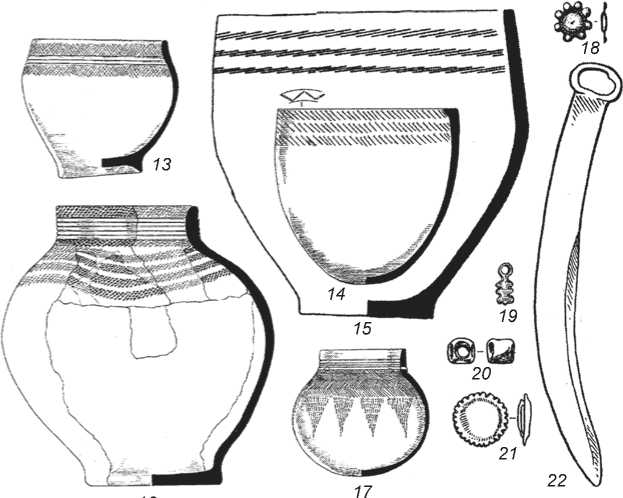

Comparison between Bainov-type sites and early complexes of the Tagar culture shows a completely different situation. These were two fundamentally different architectural traditions. Similar to Bainov burial mounds, the Podgornoye kurgans had a rectangular shape, but were elongated along the NW-SE line rather than the SW-NE line (Fig. 7, 2). This was caused by a desire to place two, three, or more graves in a row instead of one inside the main enclosure. In the Bainov type enclosures, there was only one burial in the center. Visible differences also occur in the method of erecting the walls. Horizontal stonework technique was not used in construction of enclosures at the Podgornoye stage. Enclosures were built of vertical slabs which overlapped, or two slabs were placed with a gap and were secured on the outside by a third slab. Such a system did not require a large number of buttresses (Fig. 7, 1, 3).

Enclosures of early burial mounds at the Podgornoye stage were not completely filled with soil, and their slabs rested on the edge of the subsoil or an earthen truncated-pyramidal grave structure (Fig. 7, 2 ). They usually had a noticeable inward slope. Even with complete collapse of the structure above the grave, the mound did not exert substantial pressure on the stone walls. As opposed to the Bainov enclosures, the upper edges of Podgornoye enclosures were not even, and the slabs show significant differences in height. Some of them are still clearly visible on the modern surface of the steppe. Outlying stones were quite often found near Podgornoye burial mounds; however, unlike Bainov stones, they were set not beyond the eastern corner of the enclosure, but to the southwest of it, exactly in alignment with the axis of the central grave (Fig. 7, 1 , 2 ).

The Podgornoye stage pottery tradition differed significantly from the Bainov tradition. All of their pottery can be conditionally divided into three types: slightly profiled jars (Fig. 8, 5 , 6 ), pots with bulging body and low, narrow neck (Fig. 8, 1 ), and vessels of various shapes (Fig. 8, 2–4 ). The latter were reddish or rarely black, and were carefully polished small vessels with rounded bottoms, ring-shaped base, or nipple-like legs.

Fig. 7 . Burial mound of the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture.

1 – reconstructed original appearance; 2 – ground plan of a typical burial mound; 3 – reconstructed facade of the enclosure wall.

9 10

5 cm

10 cm

21 22

Fig. 8 . Grave goods of the burials of the Podgornoye stage of the Tagar culture.

Grishkin Log I (after (Maksimenkov, 2003)): 1 – kurgan 20, grave 3; 2 , 20 – kurgan 8, grave 2; 3 – kurgan 1, grave 16; 4 – kurgan 21, grave 3; 12 – kurgan 9, grave 2; 13 – kurgan 12, grave 2; 15 – kurgan 16, grave 3; 18 – kurgan 9, grave 9; 19 – kurgan 8, grave 1; Verkh-Askiz, point 3 (excavations by N.Y. Kuzmin in 1987, 1988): 5 , 9 – kurgan 2, grave 1; 10 – kurgan 3, grave 1; Sektakh (after (Lazaretov, 2007)): 6 , 14 , 21 – kurgan 1, grave 1; Shaman-Gora (after (Bokovenko, Smirnov, 1998)): 7 – kurgan 1, grave 2; Verkh-Askiz, point 1 (excavations by N.Y. Kuzmin in 1988, 1989): 8 – kurgan 14, grave 5; 11 – kurgan 14, grave 2; 16 , 17 , 22 – kurgan 14, grave 1.

1–6 – pottery, 7 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 – 22 – bronze, 9 – bronze, gold, 10 – gold, 13 , 16 – bone.

A distinctive feature, which makes it possible to combine them into a single group, is the mandatory presence of two holes for hanging. Such vessels have been regularly found in women’s and some children’s burials of the Podgornoye period, and were absent from the complexes of the Bainov stage. Sudden emergence of this pottery type, in the context of the theory of the autochthonous origins of the Tagar culture, requires an additional valid explanation.

The two other groups of Podgornoye vessels did not differ dramatically from the Bainov pottery. Notably, the Tagar jars had a slightly different profile. Their upper, rim part was usually slightly everted, and the edge was obliquely cut outward. These vessels were molded from the bottom up rather than from the side of the rim, as was the case with the Bainov jars. There were absolutely no traces of smoothing with wood chips or toothed stamp on the Tagar pottery. Its outer surface was usually polished.

The Podgornoye spherical vessels also differed from the Bainov vessels in the design of the upper part: their necks were always low and the edge of the rim was everted.

If a visual comparison of individual Podgornoye and Bainov vessels can reveal some resemblance of their outlines, their decoration fundamentally differs. The hallmark of the Early Tagar pottery consists of so-called cornices and wide grooves. In fact, these were molded bands, one of which was located directly under the edge of the rim, and the second was 3–5 cm from it. A maximum distance between these bands was observed in the vessels from the earliest Podgornoye graves, close in time or contemporaneous with the latest Bainov complexes. Subsequently, the number of bands gradually increased, and gaps between them became smaller. Ultimately, by the final Podgornoye stage, the bands turned into a purely decorative element of drawn horizontal lines. Additional ornamentation of the Early Tagar vessels was extremely minimal; it could involve a number of pits or “pearls”, sparse oblique notches, as well as groups of stick or smooth stamp imprints. The ornamental band on the Podgornoye vessels was not located in the rim zone, as was the case with the Bainov vessels, but significantly lower, under the molded bands. It can be considered a vestige of the relief-band ware tradition, where ornamentation both performed a decorative function and contributed to stronger attachment of molded elements to the vessel body.

The tradition of using appliquéd and molded bands for pottery decoration in Southern Siberia had very deep roots. It appeared in the region already at the end of stage I (Karasuk) of the Late Bronze Age. The problem is that this tradition completely degraded by the middle of stage III (Lugavskoye), and ultimately became extinct by the end of this stage, after the same development chain that we observed in the Podgornoye vessels: 1) large appliquéd single bands in the area where the rim was attached to the body; 2) several molded bands of smaller size; 3) thin drawn lines. Neither appliquéd nor molded bands are known in the classic Bainov pottery. Sudden revival of the relief-band tradition in such an archaic version as that appearing in the Early Podgornoye complexes has no explanation from the point of view of the autochthonous origin of the Tagar culture. We believe that the origins of its reoccurrence should be sought outside the Minusinsk Basin.

A similar situation occurred with a number of widespread Tagar bronze and bone items. With the emergence of Podgornoye complexes in the Minusinsk Basin, a complete and almost simultaneous change in the entire set of female personal ornaments and small household items took place. Burials began lacking items traditional for the Late Bronze Age, such as temporal rings, four- and six-petaled plaques, paw-shaped pendants, triangular plates with punched ornamentation, as well as rings and buttons. They were replaced by numerous hemispherical plaques sewn onto a headdress (Fig. 8, 8, 9), earrings with a cone-shaped socket (Fig. 8, 10), composite three-partite pendants made of large tubular beads and bronze biconical and cylindrical stone beads (Fig. 8, 7). Buttons that remained unchanged for several centuries became replaced by bronze, stone, and bone grooved fasteners (Fig. 8, 15, 16). Previously unknown “head knives” (polished bone plates) and slotted combs with circular ornamentation appeared (Savinov, 2012: Pl. XIV, 1, 6, 7, 9, 10) (Fig. 8, 13). Some of the categories of bronze items retained their importance, but their types changed. Mirrors with a rim began appearing frequently, along with the usual disc-shaped mirrors (Fig. 8, 14); awls with a mushroom-shaped cap acquired a neck, which was round in cross-section (Fig. 8, 11, 12). Typically, the Podgornoye knives were sharpened only on one side, while Bainov knives had double-sided sharpening. Their pommels showed amazing diversity: they could be triangular, with a square loop, with a teardrop-shaped hole, bar-shaped, or tubular (Fig. 8, 18–20). Knives with a ring and half ring continued to exist. However, they differed from the Bainov knives in the smaller size of the pommel, which almost did not protrude beyond the handle, but exceeded it in thickness, forming a relief band along the perimeter of the hole.

Pommels in the animal style (Fig. 8, 21 ) have been discovered in the Podgornoye burials, albeit in small numbers. Knives with sculpted animal heads appeared in the Minusinsk Basin as early as the beginning of stage II of the Late Bronze Age. However, first of all, they differed from the Tagar items by the set of characters and methods of their rendering. Second of all, by the mid-stage III of the Late Bronze Age, this pictorial tradition declined and completely ceased to exist. We do not know a single artistic bronze item from the Bainov complexes. As in the case of relief-band pottery, one should look for an external source for the sudden revival of the Tagar animal style at a new qualitative level. Finally, the Podgornoye burials contained weaponry, such as bronze pickaxes, daggers, and arrowheads (Fig. 8, 17 , 22 ), while in Bainov complexes no traces of the emerging custom of placing weapons in graves have been observed. This tradition appeared suddenly and precisely at the moment of the Tagar culture formation.

Another specific feature of the Tagar sites was a widespread use of bronze ornaments covered with gold foil and less often entirely made of gold (Fig. 8, 9, 10) in the funerary rite. Moreover, as the evidence accumulates, an interesting regularity can be observed: the earlier the complex of the Podgornoye stage, the greater the number of such items it contains. In the late sites, gold was present mainly in elite burials, while in the early Podgornoye burials gold foil was regularly discovered even in the graves of ordinary persons. At the same time, no such finds are known from the huge number of Late Bronze Age complexes in the Minusinsk Basin, including the Bainov complexes. What could have occurred to cause the ban on using gold in the funerary rite suddenly be removed? Such a drastic event could not have occurred on its own, without a serious external impact.

Continuity between the Bainov and Podgornoye complexes is most noticeable in the funerary rite. Both had a similar design of graves and similar system of linking children’s burials. The common features included placement of the dead on their backs and variants of their orientation, presence of two vessels and their location in the graves, as well as remains of a sacrificial animal in the burial. However, in the burials of the Podgornoye stage, utensils consisting of a knife and awl were placed on the belt of the buried, as opposed to their placement on a small vessel, as was the case with the Bainov complexes. These knives were full-sized items rather than blade fragments inserted into wooden hafts. The problem is that the vast majority of the investigated Early Podgornoye burials belonged to the period of active interaction with the Bainov population. It is still unknown where the Podgornoye complexes were located and what they looked like before the initial contact between the two cultural groups.

Conclusions

All the above evidence suggests that a dramatic change in the cultural paradigm occurred in the Minusinsk Basin precisely at the time when the first Podgornoye complexes appeared, but not earlier. In all their typical features, the Bainov-type sites were natural heirs and successors of the Late Bronze Age traditions. They should be excluded from consideration of the Tagar culture and be viewed as the final stage of the Late Bronze Age.

The emergence of different kurgan architecture, the relief-band ware tradition, a number of innovative bronze and bone items, including weapons and items made in the Scytho-Siberian animal style in the Podgornoye-type complexes marks the beginning of a new period in the history of the region. These features did not have local roots and were brought to the Middle Yenisey region from outside as a result of migration processes. Based on the rapid transformation of ideological beliefs and composition of grave goods not only of prestigious, but also of ordinary nature, this migration was fairly large in scale.

However, the arrival of a new population to Southern Siberia at the turn of the 9th–8th centuries BC did not lead to complete displacement or extinction of the indigenous people. The Bainov heritage in the Tagar culture of the Scythian period can be seen quite clearly, primarily in the funerary rite traditionally followed in the area. Previously, we already identified two chronological horizons, IVa and IVb, as being part of the Bainov stage (Lazaretov, 2006: 26–28; Lazaretov, Poliakov, 2008: 46–47; Poliakov, Lazaretov, 2020). The current job would be to identify the layers of post-Bainov burials, contemporaneous with the appearance and initial existence of the Early Podgornoye complexes. These include some of the burials at the cemeteries of Byrganov V, Verkh-Askiz, point 1, and some other sites, and clearly stand out from among the main bulk of Bainov burials by a large amount of undecorated pottery, individual vessels and items of the Podgornoye appearance, as well as cases of violating the original basic principle: one burial mound – one grave. Notably, a maximum concentration of actual Bainov complexes, including those of the latest generation, has been observed in the southwestern areas of the Minusinsk Basin, where some vestiges of the previous period (e.g. in the kurgan architecture) continued to exist already in the Podgornoye time.

An equally important job would be to identify and attribute the earliest part of the Podgornoye burials, which appeared before the active interaction between the two population groups. Most of the known Podgornoye complexes already show some traces of this interaction, manifested by the funerary rite: burial of the dead in an extended supine position, presence of two vessels and their arrangement in the grave, and remains of a sacrificial animal. The location and appearance of the initial burials of the Tagar culture still remain a mystery. Judging by sporadic evidence, the population of the Early Podgornoye period might have placed the dead on the side, in a more or less crouched position. If we assume that the initial region of migration was the territory of the present day Tuva or Mongolia, the earliest Podgornoye burials might have also lacked grave goods.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out under the program for basic scientific research of the state academies of sciences, on the topic of Public Contract No. FMZF-2022-0014 “Steppe Cattle Breeding Cultures, Settled Farmers, and Urban Civilizations of Northern Eurasia in the Chalcolithic – Late Iron Age (Sources, Interaction, Chronology)”.

Список литературы The final Bronze Age in the Minusinsk basin

- Bokovenko N.A., Smirnov Y.A. 1998 Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki doliny Belogo Iyusa na severe Khakasii. St. Petersburg: IIMK RAN. (Arkheologicheskiye izyskaniya; iss. 59).

- Gryaznov M.P. 1956 Istoriya drevnikh plemen Verkhney Obi. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka. (MIA; No. 48).

- Gryaznov M.P. 1968 Tagarskaya kultura. In Istoriya Sibiri, vol. 1. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 187-196.

- Kiselev S.V. 1937 Karasukskiye mogily po raskopkam 1929, 1931, 1932 gg. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 3: 137-166.

- Kiselev S.V. 1951 Drevnyaya istoriya Yuzhnoy Sibiri. Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Lazaretov I.P. 2006 Zaklyuchitelniy etap epokhi bronzy na Srednem Yeniseye: Cand. Sc. (History) Dissertation. St. Petersburg.

- Lazaretov I.P. 2007 Pamyatniki bainovskogo tipa i tagarskaya kultura. Arkheologicheskiye vesti, iss. 14: 93-105.

- Lazaretov I.P., Poliakov A.V. 2008 Khronologiya i periodizatsiya kompleksov epokhi pozdney bronzy Yuzhnoy Sibiri. In Etnokulturniye protsessy v Verkhnem Priobye i sopredelnykh regionakh v kontse epokhi bronzy. Barnaul: Kontsept, pp. 33-55.

- Maksimenkov G.A. 2003 Materialy po ranney istorii tagarskoy kultury. St. Petersburg: Peterburg. vostokovedeniye.

- Poliakov A.V. 2005 Grebni iz kompleksov karasukskoy kultury. In Zapadnaya i Yuzhnaya Sibir v drevnosti. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 102-111.

- Poliakov A.V. 2020 Problemy khronologii i kulturogeneza pamyatnikov epokhi paleometalla Minusinskikh kotlovin: D. Sc. (History) Dissertation. St. Petersburg.

- Poliakov A.V. 2022 Khronologiya i kulturogenez pamyatnikov epokhi paleometalla Minusinskikh kotlovin. St. Petersburg: IIMK RAN.

- Poliakov A.V., Lazaretov I.P. 2020 Current state of the chronology for the palaeometal period of the Minusinsk basins in southern Siberia. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 29, art. 102125.

- Savinov D.G. 2012 Pamyatniki tagarskoy kultury Mogilnoy stepi (po rezultatam arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy 1986-1989 gg.). St. Petersburg: ElekSis.

- Teploukhov S.A. 1926 Paleoetnologicheskiye issledovaniya v Minusinskom kraye. In Etnografi cheskiye ekspeditsii 1924 i 1925 gg. Leningrad: Gos. rus. muzey, pp. 88-94.

- Vadetskaya E.B. 1986 Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki v stepyakh Srednego Yeniseya. Leningrad: Nauka.