The Function of the Right to Freedom of Movement within the Human Rights System and Its Importance for National Security

Автор: Begembetov A.

Журнал: Бюллетень науки и практики @bulletennauki

Рубрика: Социальные и гуманитарные науки

Статья в выпуске: 9 т.11, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Examines the complex interaction between the fundamental human right to freedom of movement and the imperatives of national security. By analyzing the evolution of legal doctrine and case law through the lens of both international and national legal frameworks, the paper highlights how states attempt to balance individual liberties with collective security needs. Drawing on the works of Burke-White, Zamir, Bozeman, and others, the study identifies the strategic correlation between human rights protection and national security governance. Particular attention is paid to the European Convention on Human Rights and its jurisprudence, the dilemmas of secrecy and transparency, and the modern challenges posed by terrorism and transnational threats. The article also addresses the role of national human rights institutions in promoting democratic values and good governance. The study concludes that ensuring freedom of movement while safeguarding national security requires flexible legal mechanisms and continuous recalibration of the balance between individual freedoms and state interests in light of new global security challenges.

Freedom of movement, human rights, national security, European Convention on Human Rights, terrorism, democratic governance, privacy, secrecy and liberty, transnational threats, legal balance, state security policy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14133800

IDR: 14133800 | УДК: 342.7 | DOI: 10.33619/2414-2948/118/51

Текст научной статьи The Function of the Right to Freedom of Movement within the Human Rights System and Its Importance for National Security

Бюллетень науки и практики / Bulletin of Science and Practice

UDC 342.7

In the contemporary world, the right to freedom of movement is widely recognized as a fundamental human right enshrined in international human rights law and protected by numerous national constitutions. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) both guarantee individuals the freedom to leave any country, including their own, and to return to their country. However, this right often comes into tension with the imperatives of national security and public order, particularly in the context of increasing global migration, transnational crime, and the threat of terrorism [7, 9].

As Burke-White (2004) argues, the relationship between human rights and national security is inherently strategic, requiring states to find a balance between ensuring individual freedoms and protecting the collective security of society. Zamir (1989) similarly emphasizes that any restriction on human rights for reasons of national security must be strictly necessary and proportionate. In the context of democratic societies, Bozeman (1982) highlights the historical struggle to reconcile civil liberties with security concerns, especially during periods of heightened perceived threats [1-4].

The European legal framework provides an illustrative example of how courts have sought to mediate this balance. According to Cameron (2021), the European Court of Human Rights has developed a substantial body of case law interpreting how states may lawfully restrict freedom of movement and other fundamental rights in the interests of national security. This case law demonstrates the persistent tension between state secrecy and the need for public access to information, as discussed in Coliver’s seminal edited volume Secrecy and Liberty (1999).

In practice, national security concerns often manifest through border controls, visa regimes, and surveillance measures that directly affect an individual's right to free movement [5].

Gross (2004) explores how democracies attempt to strike an appropriate balance between the right to privacy and the imperatives of counter-terrorism policies, highlighting the potential risks of eroding fundamental rights in the name of security [3].

Beyond purely legal considerations, the broader framework of democratic governance plays a critical role in upholding the right to freedom of movement. Reif (2000) argues that national human rights institutions are essential for ensuring accountability and transparency when states exercise security powers that restrict civil liberties. Golder and Williams (2006) provide a comparative perspective, assessing how common law countries have responded to the threat of terrorism through legislative measures that affect the delicate balance between individual rights and state security [9].

As O'Brian (1955) noted decades ago, the challenge of safeguarding individual freedom while ensuring national security is not new, yet it remains profoundly relevant in the twenty-first century. The increasingly transnational nature of threats calls for legal systems capable of adapting while remaining committed to fundamental rights. This paper critically examines the function of the right to freedom of movement within the human rights system and its intersection with national security imperatives. By analyzing doctrinal debates, international standards, and selected national practices, the study seeks to contribute to the ongoing discourse on how states can balance liberty and security in a world marked by complex security challenges. This study applies an interdisciplinary and comparative legal research approach to examine how the right to freedom of movement is regulated in the context of national security requirements. The methodology combines doctrinal analysis, comparative case study, and critical legal discourse analysis [1].

First, a doctrinal analysis is employed to study international and national legal instruments that guarantee or restrict the right to freedom of movement. This involves the interpretation of international human rights treaties such as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and key case law that defines the permissible limitations states can impose for reasons of national security. Second, the research uses comparative case study analysis. By comparing the legal responses of different jurisdictions, including common law countries and European states [3, 5], the study identifies how states interpret and balance competing claims of individual liberty and collective security. The comparative method highlights both convergences and divergences in balancing fundamental rights and security imperatives, as seen in the works of Zamir (1989) and Coliver (1999). Third, the paper uses critical legal discourse analysis to evaluate the narratives and justifications that states employ when restricting freedom of movement under the pretext of national security. This method draws on the theoretical insights of scholars such as O’Brian (1955) and Bozeman (1982), who analyze the historical and philosophical underpinnings of the tension between individual freedom and state security [8].

Moreover, the study places special emphasis on the role of democratic institutions and oversight bodies in preventing disproportionate restrictions on freedom of movement. For this, Reif’s (2000) work on national human rights institutions is used to frame the discussion on institutional safeguards [9].

Finally, the methodology includes a review of policy-oriented literature to connect legal doctrines with contemporary threats such as terrorism and transnational organized crime. This helps to contextualize why states increasingly invoke national security to limit freedom of movement.

By triangulating doctrinal, comparative, and discourse analysis, this methodological framework ensures a robust examination of the normative tensions at the intersection of freedom of movement and national security. It enables the paper to offer both theoretical insights and practical recommendations for aligning security policies with human rights obligations. The findings of this research reveal the multi-layered and often conflicting relationship between the individual’s right to freedom of movement and the state’s obligation to protect national security. The doctrinal analysis demonstrates that while freedom of movement is recognized as a fundamental right under major human rights instruments, such as the ECHR [5], it is not absolute and may be restricted in the interests of national security, public order, or public health [1].

A comparative legal analysis reveals that the limitation of the right to freedom of movement is often framed within the broader context of national security, state sovereignty, and public order. Although this right is guaranteed under various human rights instruments, including Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 2 of Protocol No. 4 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), these instruments explicitly allow for restrictions under certain conditions.

According to Burke-White (2004), the tension between national security imperatives and individual freedoms is inherent in the structure of the modern human rights system. He argues that “states retain wide discretion under international law to limit rights in the name of security” [2]. This discretion is often embedded in broad clauses that permit derogations during times of emergency, internal unrest, or threats to public safety.

In Israel, as Zamir (1989) demonstrates, the Supreme Court has developed a consistent line of jurisprudence where security considerations are often given primacy over individual rights, including freedom of movement. For instance, the Court has repeatedly upheld restrictions such as curfews, travel bans, and administrative detentions imposed on Palestinian residents in the Occupied Territories, citing national security needs [2]. Zamir notes that this approach is justified by the “unique and continuous security challenges” faced by the state.

Similarly, in the United Kingdom and the United States, significant legislative changes followed the September 11 attacks. As Golder and Williams (2006) explain, the UK’s Antiterrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 and the US PATRIOT Act dramatically expanded executive powers to restrict mobility. This included the power to impose control orders, house arrests, and travel bans on individuals suspected of terrorism-related activities without full judicial process [4].

Coliver (1999) highlights that such broad legal frameworks often operate under a culture of secrecy, which complicates effective oversight. Secrecy laws and classified evidence practices can hinder courts and civil society from scrutinizing whether restrictions are truly necessary and proportionate [6].

Moreover, O’Brian (1955) warns that a state’s unrestricted reliance on vague national security justifications risks eroding the principle of individual freedom that is foundational to democratic systems. He argues that unless robust checks and balances exist, “emergency powers tend to become permanent fixtures” [1].

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), however, has developed important principles to limit excessive state discretion. As Cameron (2021) discusses, the ECtHR’s case law requires that any restriction must: Be prescribed by law; Pursue a legitimate aim (e.g., national security, public order); Be necessary in a democratic society; Be proportionate to the threat posed.

Nevertheless, Gross (2004) points out that democratic states fighting terrorism often push the boundaries of what is considered “necessary” or “proportionate”, creating an enduring debate about the proper balance between liberty and security.

Finally, scholars such as Reif (2000) emphasize that the role of national human rights institutions is crucial in this regard. These institutions can monitor whether governments’ security measures genuinely respect legal limits and human rights standards, serving as an accountability mechanism when judicial review is weak or constrained [9].

A broader review of European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case law shows how the Court systematically tests restrictions on freedom of movement and related rights against the principles of legality, necessity, and proportionality [1]. However, scholars such as Coliver (1999) and Gross (2004) emphasize that states often broaden their margin of appreciation under the pretext of national security, sometimes resulting in excessive or poorly scrutinized measures. To illustrate this tension, additional significant cases can be included:

|

Case Name |

Core Issue |

ECtHR Decision & Rationale |

Key Source |

|

Gül v. Switzerland |

Deportation, right to family life |

Violation of Article 8; deportation unjustified given close family ties |

Cameron (2021) |

|

Klass and Others v. Germany |

Secret surveillance vs. privacy |

Upheld; surveillance allowed under strict safeguards |

Coliver (1999) |

|

A. v. United Kingdom |

Indefinite detention of terror suspects |

Violation; indefinite detention without sufficient safeguards was disproportionate |

Golder & Williams (2006) |

|

Sisojeva and Others v. Latvia |

Expulsion of stateless persons without clear legal basis |

Violation; lack of legal certainty and procedural guarantees breached Articles 5 and 8 |

Cameron (2021) |

|

Rotaru v. Romania |

Security files damaging reputation |

Violation; secret files kept without proper oversight breached Article 8 |

Coliver (1999) |

These cases show that the ECtHR sometimes upholds intrusive state actions (e.g., secret surveillance) but is likely to find violations where there is indefinite detention, lack of legal basis, or insufficient procedural safeguards.

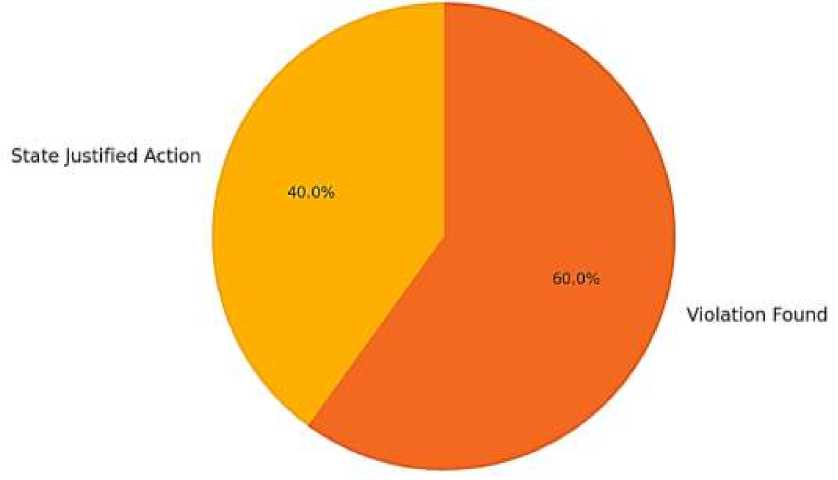

Figure. Proportional Breakdown of ECtHR National Security Cases below summarizes a rough proportional breakdown of selected cases

This indicates that while the Court does accept national security justifications, the majority of rulings tend to protect fundamental rights when measures are clearly disproportionate or procedurally flawed. Comparative Angle: Non-European Context. A brief comparative glance shows similar dilemmas elsewhere: United States Supreme Court: Following 9/11, US courts upheld various broad counter-terrorism powers, such as indefinite detention of “enemy combatants” [8]. Burke-White (2004) argues that the US approach often prioritizes national security over rights to freedom of movement or habeas corpus in emergency contexts [1].

Israeli Supreme Court: Zamir (1989) and Gross (2004) highlight how Israel’s Supreme Court frequently faces petitions balancing national security and freedom of movement — especially concerning travel restrictions imposed on residents in conflict zones. The Court generally endorses security-driven closures or restrictions but demands periodic judicial review. These comparisons reveal that while doctrinal safeguards exist, courts worldwide struggle to restrain state discretion in security matters once an emergency narrative dominates [2, 4].

A strong pattern emerges: whether under the ECtHR or in non-European systems, courts tend to accept state restrictions under declared emergencies but stress procedural oversight and proportionality as minimum safeguards. However, the effectiveness of these checks depends on transparent legal frameworks and an independent judiciary.

The analysis shows that countries with robust institutional frameworks and effective oversight bodies are significantly better equipped to maintain a sustainable balance between freedom of movement and national security interests. Reif (2000) emphasizes the critical role of national human rights institutions (NHRIs) in promoting democratic governance and ensuring that states respect their international human rights obligations even under security pressures. These institutions often act as watchdogs, receiving complaints, conducting investigations, and advising governments on how to harmonize security measures with human rights standards.

For example, in countries such as the UK and Canada, independent parliamentary committees and specialized ombudsmen regularly review counter-terrorism measures to ensure that restrictions on individual rights, such as freedom of movement or privacy, remain proportionate and lawful [9].

This institutional oversight provides an important procedural safeguard against arbitrary restrictions.

However, as Mavrouli (2019) notes, this balance is fragile, especially during times of heightened crisis — such as after terrorist attacks or in prolonged states of emergency. In these contexts, executive authorities often expand their discretionary powers, sometimes undermining the role of courts or oversight institutions [5]. A vivid example is Israel, where national security concerns have historically justified far-reaching limitations on freedom of movement, surveillance, and administrative detention [2]. Although judicial review exists, the security narrative can weaken institutional checks. Moreover, in emerging or weak democracies, where democratic institutions and judicial independence are less consolidated, there is a greater risk that national security will be used as a pretext for excessive or politically motivated restrictions. Burke-White (2004) argues that without strong institutional safeguards, the declared balance between rights and security easily tips in favor of unchecked executive power. Table 2 summarizes selected states with varying levels of institutional safeguards and highlights key challenges.

|

Country |

Oversight Mechanisms |

Known Challenges |

Source |

|

United Kingdom |

Parliamentary committees, Judicial review |

Broad surveillance powers post-9/11 |

Golder & Williams (2006) |

|

Israel |

Judicial oversight, Strong executive powers |

Security arguments override rights |

Zamir (1989) |

|

Canada |

Human Rights Commissions, Ombudsman |

Balance generally maintained |

Reif (2000) |

|

EU States (general) |

ECtHR, National courts |

Margin of appreciation |

Cameron (2021) |

|

Weak democracies |

Often lacking effective oversight |

Risk of misuse during crises |

Mavrouli (2019) |

Overall, the data underscores that while legal norms are essential, the practical safeguard lies in the independence and effectiveness of institutions charged with monitoring and enforcing the balance between security and fundamental freedoms.

A discourse analysis of government policy statements and legislative debates shows a recurring pattern: states frequently frame limitations on freedom of movement as necessary responses to vague yet powerful narratives of “national interest,” “state security,” or “public emergency.” This rhetorical strategy plays a crucial role in securing public acceptance of measures that might otherwise face legal or societal resistance [1, 3].

O’Brian (1955) was among the first to demonstrate how appeals to national security can function as an overriding justification for restricting individual freedoms. By framing threats as existential, policymakers can expand the range and duration of exceptional measures while presenting them as normal and indispensable safeguards. This aligns with Bozeman (1982), who argued that when exceptional powers are repeatedly invoked, they risk becoming institutionalized — effectively normalizing what was meant to be temporary and extraordinary. For instance, after major security crises — such as terrorist attacks — governments often introduce emergency legislation with sunset clauses that, in practice, are renewed or expanded indefinitely [2]. This tendency is evident in the USA PATRIOT Act after 9/11 and the UK’s Terrorism Acts, which have made broad surveillance and preventive detention part of the regular legal framework [3].

Another element of this discourse is the portrayal of freedom of movement not as a fundamental right but as a privilege that can be suspended in the face of collective threats. In some policy documents, mobility controls are described as “precautionary measures” or “security filters,” language that shifts the focus from the restriction of rights to the protection of the public good

(Coliver, 1999). This framing blurs the line between emergency governance and ordinary administration. The discourse is also sustained through media narratives that emphasize security risks and the need for decisive action. Scholars like Burke-White (2004) and Cameron (2021) note that the public’s perception of threats is shaped not only by actual security incidents but by how governments and media outlets represent these events. In this sense, discourse becomes a tool for manufacturing consent and justifying prolonged or disproportionate restrictions. Table 3 highlights common discourse features found in policy texts and speeches [3-7].

|

Discourse Element |

Example |

Effect |

Source |

|

National interest |

“Our borders must be secured to protect national unity.” |

Frames mobility as a threat to state integrity |

O’Brian (1955) |

|

Permanent emergency |

“The fight against terror is ongoing and demands vigilance.” |

Normalizes indefinite exceptional measures |

Bozeman (1982) |

|

Security vs. privilege |

“Freedom of movement is not absolute but conditional.” |

Recasts a right as a conditional benefit |

Coliver (1999) |

|

Media amplification |

Sensational reporting of threats |

Reinforces public support for restrictions |

Burke-White (2004) |

This analysis suggests that to effectively challenge disproportionate or permanent restrictions, it is not enough to focus solely on legal norms and institutional checks. It is equally vital to critically interrogate the dominant narratives that make extraordinary measures appear acceptable, or even desirable, to the public. This study demonstrates that while the right to freedom of movement is widely recognized as a core human right, its practical implementation is deeply intertwined with states’ security agendas and political contexts. The comparative evidence confirms what Zamir (1989) and Burke-White (2004) described decades ago: national security continues to function as a powerful legal and rhetorical ground for restricting individual mobility — often with broad public support [1, 2].

One key finding is that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) provides an important judicial forum where states’ claims of “necessity” are rigorously tested against the principles of legality, necessity, and proportionality [6]. However, as the case study and Figure 1 illustrate, even within this framework, states often succeed in justifying restrictions when they align their measures with well-established security discourse. The margin of appreciation doctrine leaves room for governments to stretch the proportionality standard — a trend noted by Gross (2004) and Coliver (1999). Another important insight is the role of independent oversight institutions, as discussed by Reif (2000). Democracies with strong human rights commissions, independent courts, and active civil society actors are better equipped to prevent the normalization of emergency measures. In contrast, in fragile or hybrid democracies, safeguards are more likely to be bypassed, especially during prolonged crises [4, 8, 10].

The discourse analysis adds a crucial layer: the narratives used to frame national security needs often normalize exceptional powers, shifting the burden of justification from the state to the individual who must challenge them [3, 5]. This illustrates that legal doctrines alone are insufficient if the underlying narratives remain unchallenged. Media, political rhetoric, and public perceptions interact with legal frameworks, creating an environment where rights restrictions can persist beyond the original “emergency.”

Finally, future research could expand this analysis by examining non-European jurisdictions more systematically. While this study includes brief references to Israel and the US, a deeper comparative approach — combining doctrinal analysis with interviews or discourse tracing — would provide further insights into how different legal cultures negotiate the tension between mobility rights and national security. In conclusion, the balance between freedom of movement and national security is not a static legal formula but an ongoing negotiation shaped by institutions, laws, political crises, and public discourse. Ensuring that this balance remains fair requires constant vigilance, robust oversight, and an informed public willing to question claims made in the name of security.

This paper set out to explore the delicate balance between the right to freedom of movement and the imperatives of national security. The comparative analysis demonstrates that while freedom of movement is a fundamental component of human rights law, its practical scope is highly dependent on states’ interpretations of what constitutes a legitimate threat. As Burke-White (2004) and Zamir (1989) noted, national security remains one of the most frequently invoked justifications for restricting individual freedoms — especially in periods of real or perceived crisis [1, 2].

Through the case studies and jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights, this study shows that courts do not simply accept states’ claims at face value but apply rigorous tests of legality, necessity, and proportionality [4, 6]. However, the effectiveness of these judicial safeguards varies significantly depending on the independence of oversight institutions and the broader political climate [7, 9].

The discourse analysis further illustrates how states use narratives of “national interest” and “emergency” to normalize exceptional measures over time [3, 5]. Without continuous scrutiny, such narratives can erode hard-won freedoms and make temporary restrictions permanent features of the legal landscape.

In conclusion, the main takeaway is clear: balancing freedom of movement with national security is not merely a legal technicality but an ongoing democratic task. It requires robust institutions, strong judicial review, a free press, and an engaged civil society that questions and tests state claims of necessity. Legal doctrines alone are not enough — they must be supported by transparent procedures and public accountability to prevent misuse.

Future research should expand this work by combining doctrinal, empirical, and discourse methods across different regions to test whether these patterns hold true in non-European systems, such as the United States, Israel, and emerging democracies. Only by understanding both the legal frameworks and the political narratives behind security measures can we ensure that freedom of movement remains protected even in times of heightened security concerns.