The Impact of Individual and Organizational Characteristics on Work Ethics- Cross-Cultural Comparison

Автор: Tahir Masood Qureshi, Marija Runic-Ristic, Vilmos Tot

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.12, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study aims to analyze the effect of individual (gender and education) and organizational (organizational sector) characteristics on work ethics in the United Kingdom, Serbia, and the United Arab Emirates. This research is centered around a survey conducted among managers, from the UK, the UAE, and Serbia. Their main task was to evaluate the aspects of the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile (MWEP) short form. The MWEP was chosen for this study as it does not explicitly address work ethics with religion, making it a suitable tool for examining work ethics across three cultures with different religious practices. This study contributes to existing literature by exploring how organizational factors influence work ethics in three countries that share business interests and have cultural and economic ties. The findings indicate that these factors have an impact on work ethics in studied countries.

Individual characteristics, MWEP, organizational characteristics, cross-cultural comparison, gender, education, human resources development, Serbia, UK, UAE

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170206565

IDR: 170206565 | УДК: 005.966 159.947.3 174.7 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2024-12-3-633-645

Текст научной статьи The Impact of Individual and Organizational Characteristics on Work Ethics- Cross-Cultural Comparison

Since work ethics represents an individual’s system of values and norms, much research has been directed at its connection with national cultures. Numerous studies have analyzed the relationship between national culture and ethics ( Chen et al., 2018 ; Perez, 2017 ; Sims and Gegez, 2004 ; Vitolla et al., 2021 ).

However, the majority of these studies either focused on Protestant Work Ethics (PWE) ( Kalemci and Kalemci Tuzun, 2019 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ) or Islamic Work Ethics ( Ali and Al-Kazemi, 2007 ; Khan et al., 2015 ; Mohammad et al., 2018 ). Recently, researchers have tried to stop analyzing work ethics in the context of religion and have paid more attention to the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile (MWEP) ( Miller et al., 2002 ). Therefore, recent cross-cultural studies have used the MWEP instrument ( Li et al., 2020 ; Meriac et al., 2013 ; Miller et al., 2002 ).

Previous studies have also analyzed and emphasized the significant influence of work ethics on employees and organizational performance ( Adeyeye et al., 2015 ; Runic-Ristic et al., 2024 ; Sapada et al., 2018 ). Moreover, the authors discovered that work ethics are related to a country’s economic development. Work ethics are higher in developed countries than in less developed countries. According to Adeyeye et al. (2015) , work ethics represent a crucial factor in organizational development and production, leading to an increase in national wealth and sustainable political stability ( Adeyeye et al., 2015 ).

The present study analyzes the relationship between work ethics and individual and organizational

characteristics by comparing three nations: the UK, the UAE, and Serbian, which differ in many ways (having different languages, religion, economic conditions, standard of living, legal, and educational systems, and finally, not having the same cultural values). In our study, we used sfMWEP ( Meriac et al., 2013 ) instrument, which is the shorter version of MWEP and consists of seven work ethics dimensions. These seven dimensions are hard work, leisure, self-reliance, morality/ethics, the centrality of work, wasted time, and delay of gratification ( Miller et al., 2002 ). We used the MWEP instrument in this study because the three cultures that we examined belong to different religions, and the advantage of this instrument is that it doesn’t analyze the work ethics from the aspect of religion compared to other instruments (e.g., the Protestant Work Ethics Questionnaire (PWE) and the Islamic Work Ethic Instrument (IWE).

In this study, we analyzed the following hypothesis:

H1: There is an interaction effect between gender and nationality on work ethic dimensions among British, UAE and Serbian managers.

H2: There is a statistically significant relationship between the education and work ethic dimensions among British, UAE, and Serbian managers.

H3: There is an interaction effect between organizational sector and nationality on work ethic dimensions among British, UAE, and Serbian managers.

The UAE has a very close economic relationship with Serbia and the UK. British expats in the UAE represent one of the largest groups of expats, and there are strong trade ties between the two countries. At the same time, Serbia represents the UAE’s most important economic partner in Southeast Europe. Therefore, it is essential to understand the influence of individual and organizational characteristics on work ethics in these three nations.

The paper is organized as follows. In the first section, we analyze the literature on the impact of individual and organizational characteristics on work ethics. In the second section, we present the methodology and results. At the end, we discuss the limitations of our study and further research.

Theoretical framework and literature review

Gender and work ethic

The position of women in the examined societies (British, UAE, and Serbian) differs in many ways, and there is a difference in gender parity among these three cultures.

The discovery of oil reserves in the UAE led to significant changes in society. It has transformed from a traditional society based on agriculture to a modern industrial society. These changes have also affected the role of Arab women in all spheres of life, particularly at work. Before modernism, women in the UAE were not active at work. However, with modernization, Emirati women have begun pursuing higher education and moving into the labor market. As a consequence of these changes, the UAE has had the highest increase in the female workforce among Arab countries over the last decade ( ILO Data Explorer, 2023 ).

The position of women in Serbian organizations is better than that of Emirati women; however, it is worse than the position of women in Western Europe, particularly the UK (Stošić et al., 2015). Serbian society is mostly male-dominant and has been especially emphasized in the past decades. The wars during the 90s, sanctions imposed by the UN, exclusion from international trade, transition and privatization only increased the crises of man’s role and withed the gap between men and women in organizations ( Arandarenko et al., 2012 ). Increased misogyny is one of the characteristics of Serbian society during the transitional process, and the position of women in Serbian society is still marginalized. The proportion of employed women (41%) in Serbia is considerably lower than that of employed men (56%) ( Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Employment, 2024 ). Although Serbian women have better qualifications than men, they are less paid, do not participate in the decision-making process, and work more in wage-paid jobs. This is in contrast to Western economies, where average employed women are less qualified than average employed men, justifying the wage gap ( Avlijaš et al., 2013 ).

Since the UK is a developed country, there is more parity between the female and male workforce. Approximately 72% of women are employed, compared to 80% of men (UK - Office for National Statistics, 2024). However, even in the UK, women are mostly present in low-paid jobs and less productive sectors (ESG and Education, 2024). There are still barriers for women to progress and build skills in the UK, and the highest positions women occupy are mostly in public administration, tourism, education, and health. Therefore, British women were less willing to enroll in STEM education.

The influence of gender on work ethics has been one of the most analyzed demographic variables. However, the results of these studies have been inconsistent. Some authors have identified that gender has minimal or no impact on work ethics ( Alsarhan et al., 2021 ; Barragan et al., 2018 ; Schminke et al., 2003 ). Others have found differences between genders in terms of work ethics, but there is also inconsistency in these results. Some studies have shown that women behave more ethically than men ( Bageac et al., 2011 ; Furnham and Rajamanickam, 1992 ; Ghorpade et al., 2006 ) others have identified that men are more ethical than women ( M. Fredricks et al., 2014 ; McInerney et al., 2010 ; Phau and Kea, 2007 ; Stam et al., 2013 ).

Authors who used the MWEP construct to analyze gender differences in work ethics have also reached inconsistent results. Meriac et al. (2010) identified no gender differences ( Meriac et al., 2010 ), whereas Ryan and Tipu (2016) found some differences ( Ryan and Tipu, 2016 ). According to their study, women consider the Centrality of Work, Hard Work, and Self-reliance to be more important than men, whereas Leisure and Wasted Time dimensions are higher for men.

Considering the inconsistency in previous findings, the following hypothesis is proposed

H1: There is an interaction effect between gender and nationality on work ethic dimensions among British, UAE and Serbian managers.

Education and work ethic

All three countries that we analyzed had different educational systems. According to the ranking of the U.S. News and World Report’s Best Countries for Education list for 2022, the UK in 2nd place right after the USA, the UAE in 28th place, and Serbia in 68th place ( The Best Countries in the World, 2022 ) their ranking is based on three factors: the level of development of the public education system, the quality of education, and whether respondents are willing to enroll in a university in that nation.

There are not so many studies that have analyzed the influence of education on work ethic as is the case with gender and age ( Gierczyk and Harrison, 2019 ). The results of these studies are inconclusive. Some authors have found that educational level has no impact on work ethics ( Keller et al., 2007 ; Lee and Tsang, 2013 ), while others have identified that an impact exists ( Asio et al., 2019 ; Ghahremani and Ghourchian, 2012 ; Yousef, 2001 ).

The authors, who discovered the influence of education on work ethics, have also come across inconsistent results. Some research found that employees with higher educational levels are more ethical ( Asio et al., 2019 ; Yousef, 2001 ), while others have revealed that employees with higher educational levels behave more unethically ( Constandt and Willem, 2019 ; Kim and Miller, 2008 ; Malloy and Agarwal, 2003 ). However, none of the previous studies tried to discover whether work ethics change with the educational level of employees by using the MWEP construct.

Considering the inconsistency in previous findings, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2: There is a statistically significant relationship between the education and work ethic dimensions among British, UAE, and Serbian managers.

Organizational characteristics and work ethics

Organizational and industry characteristics (e.g., industry type, organizational size) can also have an impact on work ethics. However, in this study, we analyzed the effect of the organizational sector on work ethics among the three nations. Only a few prior studies have investigated the effect of organizational characteristics (such as organizational type, sector, and size) on work ethics ( Ali and Al-Kazemi, 2007 ; Budhwar and Mellahi, 2016 ; Metle, 2002 ; Yousef, 2001 ), but none have used the MWEP. For instance, Yousef (2001) analyzed the influence of organizational type (manufacturing or service) and sector (government or private) on work ethics and found that employees working in service and government organizations support Islamic work ethics more than those working in private and manufacturing organizations Yousef (2001) . The results of Yousef (2001) correspond to those of Ali and Al-Kazemi (2007), which indicated that UAE managers in the public sector had a higher work ethics than managers in the private sector( Ali and Al-Kazemi, 2007 ; Yousef, 2001 ). On the other hand, Metle (2002) found that Kuwaiti managers in the public sector behave more unethically than those in the private sector ( Metle, 2002 ).

The majority of studies that have analyzed the influence of organizational factors, particularly the organizational sector, on work ethics (especially Islamic Work Ethic) have been conducted in the Arab region, and no studies have analyzed these factors in the West, particularly in Europe.

Considering the results of previous research, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: There is an interaction effect between organizational sector and nationality on work ethic dimensions among British, UAE, and Serbian managers.

Materials and Methods

The respondents in our study were British, UAE, and Serbian managers. We researched companies in the UAE and Serbia. The sample consisted of 467 managers. Of these, 153 were Serbian, 157 were Emirati, and 157 were British. The Emirati managers and Serbian managers were analyzed in Serbia and the UAE. However, British managers were surveyed in public and private companies situated in the UAE. Demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

|

Serbia |

UAE |

UK |

Total |

|

|

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

60.8 |

74.5 |

42.0 |

59.1 |

|

Female |

39.2 |

25.5 |

58.0 |

40.9 |

|

Education |

||||

|

Primary - up to 5 years |

0.0 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

|

High Schools - 10 years |

1.3 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

|

Secondary Schools - 12 years |

20.3 |

6.4 |

20.4 |

15.6 |

|

Undergraduate degree - 14 years |

49.7 |

36.9 |

49.7 |

45.4 |

|

Graduate degree - 16 years |

28.8 |

54.1 |

23.6 |

35.5 |

|

PhD degree |

0.0 |

0.6 |

6.4 |

2.4 |

|

Organizational Sector |

||||

|

Private sector |

60.0 |

76.9 |

26.8 |

53.7 |

|

Public sector |

40.0 |

23.1 |

73.2 |

46.3 |

The questionnaire consisted of two parts. In the first part, we identify the personal characteristics of the respondents such as nationality, gender, and education and characteristics of the organizations where participants worked (organizational sector:1= private, 2= public).

In the second part, we measured work ethics using the sfMWEP ( Meriac et al., 2013 ) which is the shorter version of MWEP and consists of seven work ethics dimensions. These seven dimensions are hard work, leisure, self-reliance, morality/ethics, the centrality of work, wasted time, and delay of gratification ( Miller et al., 2002 ).

Research Results

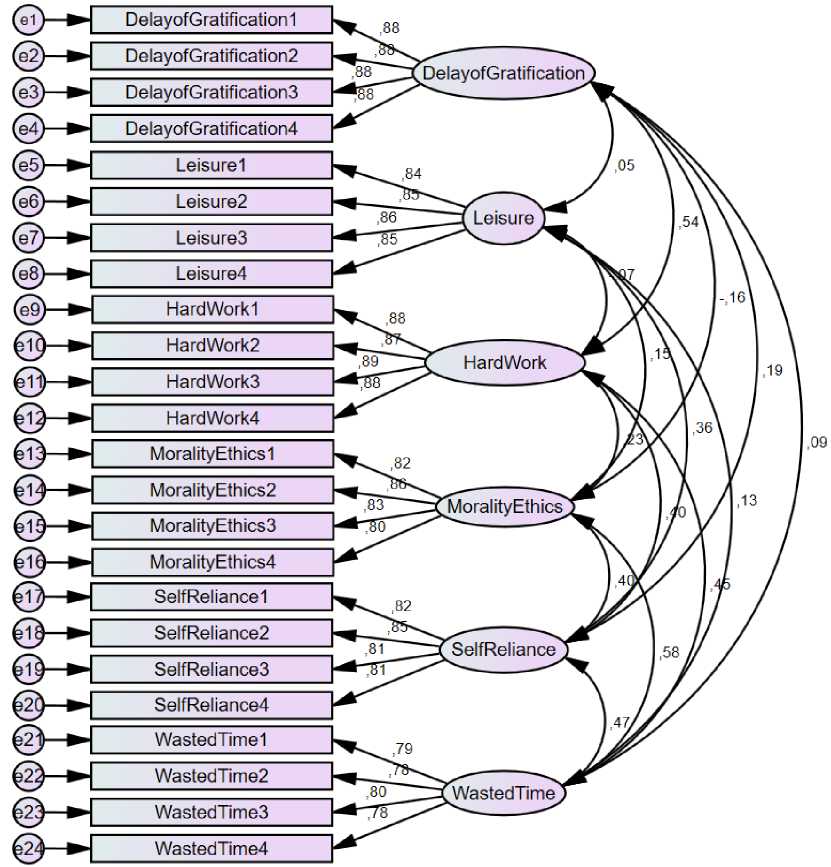

The theoretical model was first tested using Structural Equation Modelling. SEM was conducted on a sample of 467 respondents using a five-point Likert scale measuring work ethics with 28 items (Figure 1).

In our dataset, we did not have variables with missing values, three respondents were unengaged.

After conducting factor analysis, we removed four items (CentralityofWork1, CentralityofWork2, CentralityofWork3, and CentralityofWork4) because of strong factor cross-loadings. When we removed these four items, the KMO value indicated that sampling was adequate (KMO =0.906, Sig.= 0.000). All Communalities were above .607, and the six-factor model explained 71.261 of the variance. There were 0 (0,0%) non-redundant residuals with absolute values greater than 0.05. The discriminant validity showed that we had no strong cross-loadings. The Factor Correlation Matrix showed that all values are below .560

WastedTime4

|

Table 2. Factor Correlation Matrix |

||||||

|

Factor |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

1 |

0.052 |

0.519 |

-0.157 |

0.194 |

0.086 |

|

2 |

0.052 |

1 |

-0.072 |

0.149 |

0.348 |

0.127 |

|

3 |

0.519 |

-0.072 |

1 |

0.224 |

0.399 |

0.436 |

|

4 |

-0.157 |

0.149 |

0.224 |

1 |

0.39 |

0.56 |

|

5 |

0.194 |

0.348 |

0.399 |

0.39 |

1 |

0.458 |

|

6 |

0.086 |

0.127 |

0.436 |

0.56 |

0.458 |

1 |

|

Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalization |

||||||

(Table 2)

Figure 1 . Latent variables and rectangles measure variables

DelayofGratifi cation

Leisure

Ha rd Work

Moral ityEthics

SelfReliance

WastedTime

DelayofGratification 1

DelayofGratification2

DelayofGratification3

DelayofGratification4

Leisurel

Leisure 2

Leisures

Leisure4

Hard Work 1

HardWork2

Hard Work3

HardWork4

Moral ityEthics 1

MoralityEthics2

MoralityEthics3

MoralityEthics4

SelfReliancel

SelfReliance2

SelfRelianceS

SelfReliance4

WastedTimel

WastedTime2

WastedTimeS

All the Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.70 indicating that the model’s reliability is confirmed.

The AVE for all factors was above 5, and the CR for each factor was above the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Table 4). Finally, it was shown that the hypothesized model represents a good fit to the data (RMSEA=,000 CFI=1,000 CMIN=220,919 DF=237) and, thus, there was no need to conduct post-hoc modifications. (Table 4)

Table 3. The AVE

|

or o |

LU st |

o' X |

o o o o co or |

o Q O |

CD —1 |

p CD IE |

^ LU |

"O "cD o |

||

|

SelfReliance |

0.893 |

0.676 |

0.221 |

0.894 |

0.822 |

|||||

|

DelayofGratification |

0.932 |

0.774 |

0.288 |

0.932 |

0.194 |

0.88 |

||||

|

Leisure |

0.913 |

0.723 |

0.127 |

0.913 |

0.356 |

0.051 |

0.85 |

|||

|

HardWork |

0.932 |

0.775 |

0.288 |

0.933 |

0.403 |

0.537 |

-0.068 |

0.881 |

||

|

MoralityEthics |

0.895 |

0.681 |

0.338 |

0.897 |

0.399 |

-0.156 |

0.151 |

0.229 |

0.825 |

|

|

WastedTime |

0.869 |

0.625 |

0.338 |

0.87 |

0.47 |

0.087 |

0.13 |

0.447 |

0.581 |

0.79 |

After confirming the reliability of the scale and the theoretical model, we started confirming the hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

We used a two way ANOVA to examine how gender and national culture interact to influence work ethics. The respondents’ preferences for work ethic dimensions were dependent variables, while national culture and gender served as the independent variables. The ANOVA setup was framed as a 3 × 2 factorial design (culture × gender). (Table 5)

Findings revealed that significant interaction exists between gender and all three national cultures on the Self-reliance, Hard work, and Delay of gratification dimensions (Table 4)

Table 4. A significant interaction

|

F |

p |

partial η2 |

|

|

Self-reliance |

6.559 |

0.002 |

0.028 |

|

Hard Work |

7.375 |

0.001 |

0.031 |

|

Delay of Gratification |

3.428 |

0.033 |

0.015 |

A pairwise comparison identified significant differences.

The findings have discovered that a significant interaction between gender and national culture on three work ethic dimensions among the three groups of managers exists, we can conclude that H1 is confirmed.

Table 5. Means and standard deviation

|

Wasted Time |

Self-Reliance |

Morality Ethics |

Hard Work |

Leisure |

Delay of Gratification |

||||||||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

||

|

Culture X Gender |

|||||||||||||

|

UK |

Male |

3.98 |

.46 |

3.64* |

.62 |

4.23 |

.31 |

3.94* |

.72 |

3.08 |

.56 |

2.72* |

.78 |

|

Female |

4.06 |

.38 |

3.91* |

.61 |

4.24 |

.32 |

3.31* |

1.04 |

3.19 |

.73 |

2.37* |

.85 |

|

|

Serbia |

Male |

3.62 |

.47 |

3.71* |

.53 |

3.37 |

.37 |

3.77* |

.48 |

3.36 |

.60 |

3.44* |

.58 |

|

Female |

3.71 |

.55 |

3.50* |

.62 |

3.34 |

.31 |

3.69* |

.49 |

3.11 |

.67 |

3.49* |

.52 |

|

|

UAE |

Male |

3.80 |

.64 |

3.71* |

.62 |

3.60 |

.71 |

4.07* |

.79 |

2.94 |

.70 |

3.37* |

.61 |

|

Female |

3.74 |

.65 |

3.64* |

.52 |

3.83 |

.61 |

4.06* |

.71 |

2.96 |

.68 |

3.22* |

.61 |

|

|

Culture X Organizational Sector |

|||||||||||||

|

Private sector |

4.07* |

.49 |

3.78 |

.59 |

4.26 |

.30 |

3.67 |

.89 |

3.14 |

.67 |

2.45 |

.72 |

|

|

UK |

Public sector |

4.00* |

.38 |

3.80 |

.64 |

4.21 |

.32 |

3.52 |

1.00 |

3.14 |

.65 |

2.56 |

.88 |

|

Businessman/woman |

4.74* |

.00 |

4.65 |

.00 |

4.59 |

.00 |

4.30 |

.00 |

4.15 |

.00 |

2.85 |

.00 |

|

|

Others |

4.41* |

.28 |

4.00 |

.55 |

4.59 |

.02 |

4.06 |

.20 |

2.91 |

1.06 |

1.82 |

.15 |

|

|

Wasted Self-Reli- Morality Hard Work Leisure Delay of Time ance Ethics Gratification |

|

|

Private sector Public sector Serbia Businessman/woman Others |

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD 3.56* .53 3.51 .60 3.36 .39 3.66 .51 3.15 .68 3.44 .56 3.74* .48 3.72 .55 3.37 .31 3.84 .43 3.33 .57 3.51 .54 3.89* .33 3.91 .43 3.33 .24 3.74 .40 3.59 .55 3.41 .55 3.65* .35 4.00 .17 3.17 .09 3.58 .99 3.90 .01 3.51 1.02 |

|

Private sector Public sector UAE Businessman/woman Others |

3.86* .64 3.76 .56 3.71 .65 4.14 .74 2.89 .69 3.32 .57 3.72* .69 3.58 .65 3.66 .77 3.98 .82 3.04 .72 3.52 .56 3.70* .44 3.53 .48 3.15 .47 3.84 .55 3.25 .33 3.33 .30 3.50* .60 3.52 .69 3.49 .78 3.87 .88 3.05 .79 3.04 .87 |

Notes: * p<.05

Hypothesis 2

Pearson’s product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between work ethic dimensions and educational level for each of the three nationalities.

Analyses indicated that the relationship was linear. Both variables were normally distributed with no outliers.

A correlation was discovered for the UAE and British samples, whereas there was no correlation between educational level and work ethics for the Serbian sample. (Table 6)

|

Table 6. Pearson’s product-moment correlation |

Correlations

|

UK UAE Serbia |

|

|

Wasted Time Score |

Pearson Correlation .137 .259** -.028 Sig. (2-tailed) .086 .001 .734 N 157 157 149 |

|

Self Reliance Score |

Pearson Correlation .027 .191* -.036 Sig. (2-tailed) .741 .017 .659 N 157 157 149 |

|

Morality/Ethics Score |

Pearson Correlation .079 .058 .112 Sig. (2-tailed) .324 .471 .174 N 157 157 149 |

|

Hard Work Score |

Pearson Correlation .270** .143 -.045 Sig. (2-tailed) .001 .073 .587 N 157 157 149 |

|

Leisure Score |

Pearson Correlation -.100 -.148 -.047 Sig. (2-tailed) .212 .064 .569 N 157 157 149 |

|

Delay of Gratification Score |

Pearson Correlation .168* .035 -.081 Sig. (2-tailed) .035 .661 .329 N 157 157 149 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Considering our results, we can say that H2 is partially confirmed because there is no correlation between education and work ethic dimensions for the Serbian sample.

Hypothesis 3

A two way ANOVA was conducted to analyze if there is an impact on work dimensions based on the combination of organizational sector and nationality. Respondents’ preference for each work ethic dimension was a dependent variable, and the culture and organization sectors were independent variables. The ANOVA setup was framed as a 3 × 2 factorial design (culture × organizational sector). The results can be seen in Table 5.

The results revealed that there was a statistically significant interaction among all three national cultures and the organization sector on the Wasted Time (F (6,455) = 2.287, p = .035, partial η2 = .029). A pairwise comparison identified significant differences.

The results indicate that a significant interaction effect between the organizational sector and nationality on work ethic dimensions among the three groups of managers exists. Therefore, it can be said that H3 is accepted.

Discussion

The findings confirm most, but not all, of our hypotheses. These results support H1 and H3, and partially support H2.

Testing the first hypothesis of the study indicates that both gender and culture influence work ethics. To date, studies about the connection between work ethics and gender have been inconsistent. Studies that used the MWEP scale have identified inconsistent results. Our results show that males from Britain and the UAE consider the Wasted Time dimension more important than Serbian males. British male managers are expected to place greater importance on time management and that they do not spend much time nurturing social contacts at work because they belong to a low-context and individualistic culture. Moreover, they belong to a masculine culture in which employees are more competitive, people are more ambitious, and material success is highly appreciated. Since “time is money,” they try not to waste time at work. However, since the UAE belongs to a high-context and collectivistic culture, we do not expect UAE male managers to value the Wasted Time dimension. They should be more oriented towards fostering personal relationships at work, which is usually time-consuming. Perhaps such a result can be ascribed to the fact that the UAE scores 50 on the masculinity dimension, which means that it is neither a Masculine nor Feminine culture ( Hofstede, 2001 ). Thus, UAE male managers from our sample express more characteristics of masculine culture. The results could have been different if we had analyzed another profession that was not as competitive as the management profession.

The fact that the Self-reliance dimension is significantly higher for British females than for Serbian females indicates that British female managers are more oriented towards achievement and selffulfillment than their Serbian female counterparts are. The lack of need for achievement among Serbian females can be a consequence of the fact that they work in a transitional economy characterized by a deteriorating economic situation and lack of employment opportunities, especially for women ( Linz and Luke Chu, 2013 ). Therefore, women in Serbian society rarely have the opportunity to choose jobs that would fulfill them and where they would be able to express a need for accomplishment.

The results of our research demonstrate that British females consider the Hard Work dimension to be less important than the other two groups of females. On the other hand, UAE females expressed a significantly higher mean score for this dimension than Serbian females. British females, who come from an economically developed Western country, have more opportunities for promotion than females from an underdeveloped economy in the East, such as the Serbian economy. Moreover, British females have better opportunities than UAE females who live in societies where female roles are still constrained to traditional roles. When Serbian and UAE female managers encounter a “glass ceiling.” which inhibits their success, they might believe that they are going to overcome these barriers by expressing hard work. This is especially the case with UAE female managers, who still live mostly in a male-dominant and traditional society. Traditionally, Arab women were expected to be confined and devoted to their families (Read, 2003). Although the UAE has had the highest increase in the female workforce among Arab countries over the last decade, less than 50% of UAE females participate in the total UAE workforce (ILO Data Explorer, 2023). Therefore, it is expected that UAE females express a higher mean for the Hard Work dimension compared to the other two groups of females.

Testing of the second hypothesis of the study partially identified that there is a relationship between educational level and work ethics among members of different nationalities. A relationship was discovered for the UAE and British samples, while there was no relationship between educational level and work ethics for the Serbian sample.

Thus far, the results of previous studies that have analyzed the influence of education on work ethics have also been inconclusive. The results of our study are also inconsistent if we consider that we have not identified any impact of education on work ethics in the Serbian sample. On the other hand, UAE managers who are more educated value the Leisure and Self-reliance dimensions more than less-educated UAE managers, while British managers with a higher level of education consider the Hard Work and Delay of Gratification dimensions to be more important than their less-educated counterparts.

Testing the third hypothesis revealed that the organizational sector and culture affect managers’ work ethics. Both British and Emirati managers who work in the private sector have statistically higher means for the Wasted Time dimension than Serbian managers do. Serbian managers who work in the private sector have a lower mean for this dimension, which is probably the result of the fact that they work in an economy in transition where the effort and excellence of employees are still not appreciated and rewarded enough. Currently, the unemployment rate in Serbia is high, leading to a decrease in the living standards of citizens and an increase in the poverty rate ( Gallyamova, 2015 ). Therefore, employers in the private sector in Serbia mostly do not treat employees as valuable assets that cannot be easily replaced, and they do not find it necessary to reward high performance. They believe that they can easily find new employees in the labor market. This attitude decreases employees’ motivation and willingness to be more efficient and productive. Although there are no significant differences between these two sectors within each culture, managers in the private sector for all three groups have higher means for the Wasted Time dimension than do managers in the public sector. For managers who work in the private sector, it is more important to be more efficient and productive than for managers from the public sector because their salaries and incentives are usually aligned with their work performance. In the public sector, compensation is more balanced and less aligned with individual performance ( Heinrich and Marschke, 2010 ; Speklé and Verbeeten, 2014 ). Moreover, in the public sector, there is less chance that one will lose their jobs if they underperform, whereas this is not the case in the private sector.

Managers from the UAE who work in the private sector express a statistically higher mean for the Self-reliance dimension than Serbian managers. We have also identified that UAE managers in the private sector value this dimension more than those in the public sector, while the situation in Serbia is the opposite. UAE managers in the private sector seek more independence and have a higher need for accomplishment than their Serbian counterparts, because their work and contributions are more appreciated by superiors. They have more opportunities for promotion, and their ideas and innovation are highly appreciated, but this is not the case in most private companies in Serbia. These results are supported by Schwartz and Bardi’s (1997) findings, which report that if the reward is equal for most employees, it hinders their willingness to make more effort and strive to achieve more at work ( Schwartz and Bardi, 1997 ).

Another interesting finding that we have not expected is that British managers employed in the public sector show a significantly lower mean for the Hard work dimension compared to their Serbian counterparts. In Serbia, as in most transitional economies, employment in the public sector is usually acquired through political and personal connections, and most often, it is not a matter of individual qualifications. Therefore, we believe that Serbian managers from our sample who work in the public sector will express a significantly lower mean for Hard work ethics compared to the other two groups of respondents who work in the public sector.

Conclusion

Although it is clear that cultural background influences employees’ work ethics, organizations with a diversified workforce also need to pay attention to the gender and educational level of employees. Higher scores for hard work ethics among Serbian and Emirati females indicate that they should be given more career opportunities and more autonomy at their workplace. The higher support for female work engagement in these cultures might increase Self-reliance on work ethics among the female workforce.

The results show that Serbian managers working in the private sector express a lower mean for Wasted time, Self-reliance, and Hard work dimensions, which can provide valuable insights for international companies operating in this region. Serbian managers in the private sector are usually underpaid and high performers are not rewarded and appreciated. International companies that employ the Serbian workforce should pay special attention to rewarding high performance to encourage Serbian managers to nurture more of these ethical dimensions.

We believe that our study has several limitations. The first limitation refers to the instrument. By using a comparative approach, we examined differences in work ethic among analyzed nationalities. Since we analyzed cultural dimensions from the aspect of nationality, we did not pay attention to individual differences within cultures. Even the criticisms of Hofstede’s concepts point out that we should consider individual differences among members of one culture (Kirkman, Lowe, and Gibson, 2006). For future research, we would recommend that cultural dimensions should be measured at the individual level.

The second limitation refers to the sample. The British sample was not equivalent to the UAE and Serbian sample. The British sample consists of British expatriates who were UAE residents, and previous studies have shown that the behavior of expatriates can be changed by the influence of the new country ( Boonsathorn, 2007 ). Thus, if the sample consists of expatriates, future research should include the number of years expatriates have lived in the host country as the significant variable of the study.

The third limitation regards the number of respondents in our research. We believe that it is not large enough to generalize the findings. For future research, we would recommend that it should include more respondents.

We have contributed to the current literature using the MWEP scale to analyze the link between work ethics and individual and organizational characteristics. So far, only two studies have analyzed the link between gender and work ethics using the MWEP scale, and none have analyzed the influence of education and organizational characteristics on work ethics using the MWEP scale.

We extend the current literature by analyzing the connection between work ethics and individual and organizational characteristics among three nations that share business interests. Previous studies have been conducted on the population of students or employees in a particular sector. Our respondents had full-time employment and were from different sectors and companies. Furthermore, none of the previous studies have analyzed three countries that are both culturally and economically different and that share business interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the respondents who participated in the research and the reviewers whose constructive suggestions significantly enhanced the quality of this work.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.Q., M.R.R. and V.T.; methodology, T.M.Q. and M.R.R.; software, V.T.; formal analysis, M.R.R., and V.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.Q. and M.R.R.; writing—review and editing, M.Q. and M.R.R; Analysis, discussion and conclusion, T.M.Q., M.R.R. and V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Список литературы The Impact of Individual and Organizational Characteristics on Work Ethics- Cross-Cultural Comparison

- Adeyeye, O. J., Adeniji, A. A., Osinbanjo, A. O., and Oludayo, O. O. (2015). Effects of workplace ethics on employees and organisational productivity in Nigeria.

- Ali, A. J., and Al-Kazemi, A. A. (2007). Islamic work ethic in Kuwait. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 14(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600710745714 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/13527600710745714

- Alsarhan, F., Ali, S., Weir, D., and Valax, M. (2021). Impact of gender on use of wasta among human resources management practitioners. Thunderbird International Business Review, 63(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22186 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22186

- Arandarenko, M., Vujić, S., Avlijaš, S., Vladisavljević, M., and Ivanović, N. (2012). Gender Pay Gap in the Western Balkan Countries: Evidence from Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. http://dcs.ien.bg.ac.rs/id/eprint/40

- Arslan, M. (2001). The work ethic values of protestant British, Catholic Irish and Muslim Turkish managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 31, 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010787528465 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010787528465

- Asio, J. M. R., Riego de Dios, E., and Lapuz, A. M. (2019). Professional skills and work ethics of selected faculty in a local college. Asio, JMR, Riego de Dios, EE, and Lapuz, AME (2019). Professional Skills and Work Ethics of Selected Faculty in a Local College. PAFTE Research Journal, 9(1), 164–180.

- Avlijaš, S., Ivanović, N., Vladisavljević, M., and Vujić, S. (2013). Gender pay gap in the Western Balkan countries: Evidence from Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. FREN-Foundation for the Advancement of Economics.

- Bageac, D., Furrer, O., and Reynaud, E. (2011). Management Students’ Attitudes Toward Business Ethics: A Comparison Between France and Romania. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0555-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0555-5

- Barragan, S., Erogul, M. S., and Essers, C. (2018). ‘Strategic (dis) obedience’: Female entrepreneurs reflecting on and acting upon patriarchal practices. Gender, Work and Organization, 25(5), 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12258 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12258

- Berengaut, J., and Muniz, C. (2005). United Arab Emirates Staff Report for the 2005 Article IV Consultation. Staff Representatives for the 2005 Consultation with the United Arab Emirates,Dubai.

- Boonsathorn, W. (2007), “Understanding conflict management styles of Thais and Americans in multinational corporations in Thailand”, International Journal of Conflict Management, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 196–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/10444060710825972 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/10444060710825972

- Budhwar, P. S., and Mellahi, K. (2016). The Middle East context: An introduction. Handbook of Human Resource Management in the Middle East, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784719524.00007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784719524.00007

- Chen, C., Gotti, G., Kang, T., and Wolfe, M. C. (2018). Corporate Codes of Ethics, National Culture, and Earnings Discretion: International Evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(1), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3210-y DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3210-y

- Constandt, B., and Willem, A. (2019). The trickle-down effect of ethical leadership in nonprofit soccer clubs. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 29(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21333 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21333

- ESG and Education: Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). (2024, February 23). Global Business Coalition for Education. https://gbc-education.org/esg/education-and-esg-materiality/esg-and-education-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-dei/

- Forstenlechner, I., Madi, M. T., Selim, H. M., and Rutledge, E. J. (2012). Emiratisation: Determining the factors that influence the recruitment decisions of employers in the UAE. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(2), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561243 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561243

- Furnham, A., and Rajamanickam, R. (1992). The Protestant Work Ethic and Just World Beliefs in Great Britain and India. International Journal of Psychology, 27(6), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599208246905 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599208246905

- Gallyamova, D. Kh. (2015). Development of the Countries with a Transition Economy. Procedia Economics and Finance, 24, 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00656-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00656-5

- Ghahremani, J., and Ghourchian, G. N. (2012). Investigating Effective Factors on the Teacher’s Work Ethics of Three Educational Levels to represent a Model. American Journal of Scientific Research, 54, 101–110.

- Ghorpade, J., Lackritz, J., and Singh, G. (2006). Correlates of the Protestant Ethic of Hard Work: Results From a Diverse Ethno-Religious Sample. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(10), 2449–2473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00112.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00112.x

- Gierczyk, M., and Harrison, T. (2019). The effects of gender on the Ethical Decision-making of Teachers, Doctors and Lawyers. https://czasopisma.marszalek.com.pl/images/pliki/tner/201901/tner5512.pdf DOI: https://doi.org/10.15804/tner.2019.55.1.12

- Heinrich, C. J., and Marschke, G. (2010). Incentives and their dynamics in public sector performance management systems. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(1), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20484 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20484

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Recent Consequences: Using Dimension Scores in Theory and Research. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580111002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580111002

- ILO Data Explorer. (2023). Labour force participation rate by sex and age / ILO modelled estimates, nov 2022 (%)—Annual. https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/arab-states/

- Kalemci, R. A., and Kalemci Tuzun, I. (2019). Understanding Protestant and Islamic Work Ethic Studies: A Content Analysis of Articles. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3716-y DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3716-y

- Keller, A. C., Smith, K. T., and Smith, L. M. (2007). Do gender, educational level, religiosity, and work experience affect the ethical decision-making of U.S. accountants? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2006.01.006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2006.01.006

- Khan, K., Abbas, M., Gul, A., and Raja, U. (2015). Organizational Justice and Job Outcomes: Moderating Role of Islamic Work Ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1937-2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1937-2

- Kim, N. Y., and Miller, G. (2008). Perceptions of the Ethical Climate in the Korean Tourism Industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 941–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9604-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9604-0

- Kirkman, B. L., Lowe, K. B., & Gibson, C. B. (2006). A quarter century of culture’s consequences: A review of empirical research incorporating Hofstede’s cultural values framework. Journal of international business studies, 37, 285-320. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400202 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400202

- Kolthoff, E., Erakovich, R., and Lasthuizen, K. (2010). Comparative analysis of ethical leadership and ethical culture in local government: The USA, The Netherlands, Montenegro and Serbia. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(7), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011078879 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011078879

- Lee, L. Y.-S., and Tsang, N. K. F. (2013). Perceptions of Tourism and Hotel Management Students on Ethics in the Workplace. Journal of Teaching in Travel and Tourism, 13(3), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2013.813323 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2013.813323

- Li, J., Huang, M.-T., Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, A., Wang, Y., and Yang, X. (2020). Development and validation of work ethic instrument to measure Chinese people’s work-related values and attitudes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 31(1), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21374 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21374

- Linz, S. J., and Luke Chu, Y.-W. (2013). Work ethic in formerly socialist economies. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.07.010 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.07.010

- M. Fredricks, S., Tilley, E., and Pauknerová, D. (2014). Limited gender differences in ethical decision making between demographics in the USA and New Zealand. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 29(3), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-08-2012-0069 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-08-2012-0069

- Malloy, D. C., and Agarwal, J. (2003). Factors influencing ethical climate in a nonprofit organisation: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8(3), 224–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.215 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.215

- McInerney, M. L., Mader, D. D., and Mader, F. H. (2010). Gender Differences In Responses To Hypothetical Business Ethical Dilemmas By Business Undergraduates. Journal of Diversity Management (JDM), 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v5i1.804 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v5i1.804

- Meriac, J. P., Woehr, D. J., and Banister, C. (2010). Generational Differences in Work Ethic: An Examination of Measurement Equivalence Across Three Cohorts. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9164-7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9164-7

- Meriac, J. P., Woehr, D. J., Gorman, C. A., and Thomas, A. L. E. (2013). Development and validation of a short form for the multidimensional work ethic profile. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(3), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.01.007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.01.007

- Metle, M. Kh. (2002). The influence of traditional culture on attitudes towards work among Kuwaiti women employees in thepublic sector. Women in Management Review, 17(6), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420210441905 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420210441905

- Miller, M. J., Woehr, D. J., and Hudspeth, N. (2002). The Meaning and Measurement of Work Ethic: Construction and Initial Validation of a Multidimensional Inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(3), 451–489. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1838 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1838

- Mohammad, J., Quoquab, F., Idris, F., Al-Jabari, M., Hussin, N., and Wishah, R. (2018). The relationship between Islamic work ethic and workplace outcome: A partial least squares approach. Personnel Review, 47(7), 1286–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2017-0138 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2017-0138

- Oliver, N. (1990). Work Rewards, Work Values, and Organizational Commitment in an Employee-Owned Firm: Evidence from the U.K. Human Relations, 43(6), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679004300602 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679004300602

- Perez, R. J. (2017). Leadership, Power, Culture, and Ethics in the Transcultural Context. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 19(8), 63–68. https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JABE/article/view/668

- Phau, I., and Kea, G. (2007). Attitudes of University Students toward Business Ethics: A Cross-National Investigation of Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9156-8 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9156-8

- Read, J. G. (2003). The Sources of Gender Role Attitudes among Christian and Muslim Arab-American Women. Sociology of Religion, 64(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3712371 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3712371

- Runić-Ristić, M., Savić Tot, T., Ljepava, N. and Tot, V. (2024). Work ethic, cultural impact and perceived performance – innovative insights from three countries. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-06-2023-0203 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-06-2023-0203

- Ryan, J. C., and Tipu, S. A. A. (2016). An Empirical Alternative to Sidani and Thornberry’s (2009) ‘Current Arab Work Ethic’: Examining the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile in an Arab Context. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(1), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2481-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2481-4

- Sapada, A. F. A., Modding, H. B., Gani, A., and Nujum, S. (2018). The effect of organizational culture and work ethics on job satisfaction and employees performance. INA-Rxiv. https://doi.org/10.31227/osf.io/gcep4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31227/osf.io/gcep4

- Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., and Miles, J. A. (2003). The Impact of Gender and Setting on Perceptions of Others’ Ethics. Sex Roles, 48(7), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022994631566 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022994631566

- Schwartz, S. H., and Bardi, A. (1997). Influences of Adaptation to Communist Rule on Value Priorities in Eastern Europe. Political Psychology, 18(2), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00062 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00062

- Sidani, Y. M., and Thornberry, J. (2010). The Current Arab Work Ethic: Antecedents, Implications, and Potential Remedies. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0066-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0066-4

- Sims, R. L., and Gegez, A. E. (2004). Attitudes towards Business Ethics: A Five Nation Comparative Study. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000024708.07201.2d DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000024708.07201.2d

- Speklé, R. F., and Verbeeten, F. H. M. (2014). The use of performance measurement systems in the public sector: Effects on performance. Management Accounting Research, 25(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2013.07.004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2013.07.004

- Stam, K., Verbakel, E., and De Graaf, P. M. (2013). Explaining Variation in Work Ethic in Europe. European Societies, 15(2), 268–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2012.726734 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2012.726734

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Employment. (2024). https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/oblasti/trziste-rada/registrovana-zaposlenost/

- Stošić, D., Stanković, J., Milić, V. J., and Radosavljević, M. (2015). Glass ceiling phenomenon in transition economies-the case of south eastern serbia. Facta Universitatis, Series: Economics and Organization, 11(4), 309–317.

- The Best Countries in the World. (2022). https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/rankings

- UK - Office for National Statistics. (2024). https://www.ons.gov.uk/

- Vitolla, F., Raimo, N., Rubino, M., and Garegnani, G. M. (2021). Do cultural differences impact ethical issues? Exploring the relationship between national culture and quality of code of ethics. Journal of International Management, 27(1), 100823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2021.100823 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2021.100823

- Yousef, D. A. (2001). Islamic work ethic – A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Personnel Review, 30(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480110380325 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480110380325

- Zhang, Q., Cao, Y., and Tian, J. (2021). Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggressive Cognition and Aggressive Behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0676 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0676