The importance of organizational culture for humanitarian operations

Автор: Milošević Nikola, Mišić Milan, Matić Nemanja

Журнал: Ekonomski signali @esignali

Статья в выпуске: 1 vol.16, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The humanitarian setting poses a number of challenges to organizations, so it is important to respond in an adequate way. Organizational culture is a significant factor in organizational performance and can be a deciding factor between success and failure. Every organization has its own unique culture, whether management is aware of it or not. In order to perform in the most efficient way and to be able to carry the strategy into effect properly, humanitarian organizations need an adequate and strong organizational culture. Then, to strengthen the team's sense of purpose and help it move in a unified direction humanitarian principles and standards are developed. For the development of the organization timely establishment of value systems and patterns of behavior is very important. Organizational culture is important for internal structure as well as for external bonds among participants.

Organizational culture, humanitarian organization, cooperation, humanitarian operations

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170204060

IDR: 170204060 | DOI: 10.5937/ekonsig2101061M

Текст научной статьи The importance of organizational culture for humanitarian operations

Every organization in the world has its own organizational culture, whether aware of it or not. Culture is an important factor when it comes to employee and manage-ent behavior, as well as the connection among them. Organizational cul- ture is found to be applicable in every business around the globe but the types of cultures would differ. An organization’s culture has an impact on both their work lives as well as their personal lives. Timely establishment of value sys— tems and patterns of behavior is very important for the development

Milošević N. et al., The Importance of Organizational Culture for Humanitarian

Operations of the organization. The importance of organizational culture even nowadays can be overlooked. Some organizations don’t take it seriously, and if not taken seriously side effects could be triggered. Thus, if leaders understand the culture the right way, the organization’s goals and ob0ectives can be achieved more efficiently. Otherwise, if not, the culture can become an obstacle towards the organization’s best performance. Nonprofit organizations as well need to take care of organizational culture. If they fail to recognize culture’s important role, the ability to complete the mission they are created for in the first place is endangered. This is especially important for humanitarian organizations because their aim and purpose are specific. $lso, the role those organizations have is unique and requires a different approach.

This paper consists of four parts, where each of them shows the importance of organizational culture. The paper findings show that organizational culture has a significant role in humanitarian response efforts and the overall humanitarian functioning.

2. Organizational culture

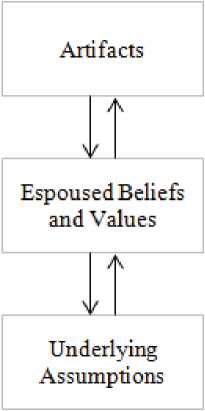

Schein [2004] describes three levels of organizational culture as it’s shown within figure 1:

-

1. 9isible organizational structures and processes (hard to decipher) such as the architecture of its physical environment; its language; its technology and products; its artistic creations; its style, as embodied in clothing, manners of address, emotional displays, and myths and stories told about the organization; its published lists of values; its observable rituals and ceremonies; and so on.

-

2. Strategies, goals, philosophies (espoused 0ustifications). $ set of beliefs and values that become embodied in an ideology or organizational philosophy thus can serve as a guide and as a way of dealing with the uncertainty of intrinsically uncontrollable or difficult events.

-

3. Unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings, and so on (ultimate source of values and action). Basic assumptions, like theories-in-use, tend to be nonconfrontable and nondebatable, and hence are extremely difficult to change

Figure 1. Levels ofculture

Organizational culture, among others, serves to (1) set boundaries between one organization and others, (2) foster a sense of identity for its members; (3) foster a shared rather than individual commitment; (4) enhance social stability, and (5) be the mechanisms for the creation of

Milošević N. et al., The Importance of Organizational Culture for Humanitarian Operations meaning and control that guide and shape the attitudes and behaviors of members of the organization. [Robbins & Judge, 2012]

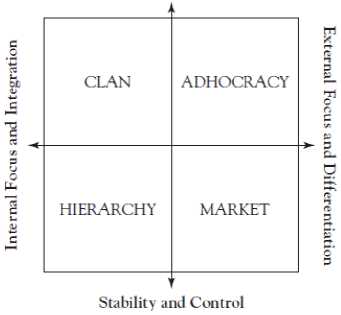

Quinn [2006]. This instrument helps define the organizational culture type based on a typology matrix. OC$I uses six dimensions to develop the organizational culture type. They are (a) dominant characteristics, (b) organizational leadership, (c) management of employees, (d) organizational glue, (e) strategic emphases, and (f) criteria of success. The OC$I, therefore, is an instrument that allows you to classify the organization into one of the four categories: hierarchy, market, clan, and adhocracy culture. These categories are shown in figure 2.

Flexibility and Discretion

Figure 2. The competing values framework

The collective acceptance and submission to the values, standards, attitudes, and behavior patterns will have a positive impact on the set of elements of the organizational culture mutually perceived and shared by the employees, which will make it stronger. [Szczepańska

The Cultural Web identifies six interrelated elements that help to make up the "paradigm" - the pattern or model - of the work environment. By analyzing the factors in each, it is possible to see the bigger picture organization’s culture: what is working, what isn't working, and what needs to be changed. The six elements shown in figure 3 are: [Johnson et al., 2012]

- Stories - The past events and people talked about inside and outside the organization. Who and what the organization chooses to immortalize says a great deal about what it values, and perceives as great behavior.

- Rituals and Routines - The daily behavior and actions of people that signal acceptable behavior. This determines what is expected to happen in given situations, and what is valued by management.

- Symbols - The visual representations of the organization including logos, how plush the offices are, and the formal or informal dress codes.

- Organizational Structure - This includes both the structure defined by the organization chart, and the unwritten lines of power and influence that indicate whose contributions are most valued.

- Control Systems - The ways that the organization is controlled. These include financial systems, quality systems, and rewards (including the way they are measured and distributed within the organization).

- Power Structures - The pockets of real power in the organization. This may involve one or two key senior executives, a whole group of executives, or even a department. The key is that these people have the greatest amount of influence on decisions, operations, and strategic direction.

Control

Systems

Rituals Я

Routines

Orcamzations

Structures

Figure 3. Cultural web model

It is also necessary to mention the subculture since it is a crucial factor of organizational culture acceptance and stability. The theory sees subculture as a set of understandings or meanings shared by a group of people. [Louis, 1985] It means each culture is divided into different parts, such as levels, branches, professional, regional, national, and other groups. Pet, several different subcultures can coexist within an organization. $t least three types of subcultures are conceivable: enhancing, orthogonal, and countercultural (Martin & Siehl, 1983). Enhancing subculture could respect the values of the dominant culture stronger than the rest of the organization. Orthogonal subculture accepts the values of the dominant culture and their own, non-conflicting set of values. Counterculture is a set of values that could present a direct challenge to the core values of a dominant culture. $lthough several subcultures could exist it does not mean they are in conflict. Moreover, they can create a synergistic effect and improve the overall performance of the organization.

3. Organizational culture in humanitarian context

When emergencies occur good coordination is necessary. Good coordination means delivering assistance by humanitarian organizations timely. The primary goal is to save lives and belongings of beneficiaries. In order to perform in the most efficient way and to be able to carry the strategy into effect properly, humanitarian organizations need an adequate and strong organizational culture. $s a humanitarian organization develops from the time of its original incorporation, the attitudes, beliefs, and behavior of its personnel become established and routinized into rules, rituals, values, codes of conduct, and standard operating procedures. [Walkup, 1997] Then, the developed organizational culture is reinforced by newcomers as they accept and enhance it over time. Consequently, the culture can fortify organizational structure and increase permanence through an evolutionary process. $pparently, organizational cultures evolve and change in accordance with environmental factors which affect organizations.

Not only do cultural dynamics influence the internal workings of the organization, they also affect humanitarian organizations’ belief systems, behavior, and performance in terms of their relations with: [Walkup, 1997]

-

- each other (e.g. how HOs engage the politics and logistics of coordination);

-

- the state authorities (e.g. how HOs perceive and respond to state attempts to coordinate and regulate HO operations);

-

- the affected populations (eg. how personnel communicate and operate with their clients and to what extent HOs incorporate truly participatory approaches to the policy process);

-

- donors (e.g. how HOs raise funds and negotiate accountability).

Organizational culture is important for humanitarian organizations where, besides employees, plenty of volunteers are present. Humanitarian ambassadors promote the culture of helping and volunteering as part of organizational culture. Sometimes, they would not be able to spend enough time within the organization to acquire all guidelines properly, but the culture can help to shorten the learning process. Some countries have been developing the culture of volunteering through the education system. Then, it affects their perception, beliefs, and assumptions towards humanitarian awareness. $s a consequence, they could be more willing to work as volunteers and could be able to outperform people without a humanitarian background of any sort. Often staff can work long hours in risky and stressful conditions. The sense of purpose developed through organizational culture can help them persist and do their best.

Table 1. Humanitarian principles

|

Red Cross & Red Crescent |

UNOCH$ |

|

Humanity |

Humanity |

|

Neutrality |

Neutrality |

|

Impartiality |

Impartiality |

|

Independence |

Independence |

|

9oluntary service |

|

|

Unity |

|

|

Universality |

The Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and $ccountability (CHS) sets out nine Commitments that organizations and individuals involved in humanitarian response can use to improve the quality and effectiveness of the assistance they provide: [Sphere, 2014]

-

- Humanitarian response is appropriate and relevant - Communities and people affected by crisis receive assistance appropriate to their needs.

-

- Humanitarian response is effective and timely - Communities and people affected by crisis have access to the humanitarian assistance they need at the right time.

-

- Humanitarian response

strengthens local capacities and avoids negative effects - Communities and people affected by crisis are not negatively affected and are more prepared, resilient and less at-risk as a result of humanitarian action.

-

- Humanitarian response is based on communication, participation and feedback - Communities and people affected by crisis know their rights and entitlements have access to information and participate in decisions that affect them.

-

- Complaints are welcomed and addressed - Communities and people affected by crisis have access to safe and responsive mechanisms to handle complaints.

-

- Humanitarian response is coordinated and complementary -Communities and people affected by crisis receive coordinated, complementary assistance.

-

- Humanitarian actors continuously learn and improve - Communities and people affected by crisis can expect delivery of

improved assistance as organizations learn from experience and reflection.

Staff are supported to do their 0ob effectively and are treated fairly and equitably - Communities and people affected by crisis receive the assistance they require from competent and wellmanaged staff and volunteers.

Resources are managed and used responsibly for their intended purpose - Communities and people affected by crisis can expect that the organizations assisting them are managing resources effectively, efficiently and ethically.

|r Communities and people i affected <

X by crisis /

Complaints are welcomed and addressed.

Humanitarian response is appropriate and relevant.

Humanitarian response is effective and timely.

Humanitarian response is coordinated and complementary.

Humanitarian response is based on communication, participation and feedback. ,

Г Staff are 1 supported to do their job effectively, and are treated

L fairly and equitably. ^B

Humanitarian actors continuously learn and improve.

Humanitarian response strengthens local capacities and avoids negative L effects. ^

Resources are managed and used responsibly for their intended purpose.

pjep°®^

Figure 4. The Core Humanitarian Standard

The Standard is shown in figure 4. It serves as a useful tool for promoting an effective response within an organization and among participants, and for overcoming inconsistency and unpredictability.

Staff is dealing with individuals who are dissimilar to them. Culturally embedded interpretations of and responses to risk are also present among aid organizations. [Johnson et al., 2016] Disaster aid is increasingly globalized, bringing together multiple actors whose perceptions, priorities, and modes of working have developed in different cultural contexts [Hewitt 2012]. Thus, misunderstanding, the effectiveness compromising of disaster risk reduction efforts can arise.

Regional and local humanitarian departments are influenced by local culture and by the culture of the parent organization or by the head of the organization. Managers and employees are from the same country or from different countries with different cultural backgrounds. $mong employees within an organization conflicts could arise as a consequence of opposite thinking and acting in a variety of different situations, especially on the field. $dditionally, subcultures can emerge as a consequence of national culture disparity. $lso, the risk is another potential point of conflict. 9arious groups perceive risk differently. Reasons may vary, but the most common are life experience, cultural background, and education. [Cohn et al., 1995; Renn & Rohrmann, 2000; Righi et al., 2021] External actors may pro0ect their cultural biases on communities and bypass existing social arrangements, distributing aid in a way that is inequitable and culturally irrelevant. [Kruks-Wisner, 2010]

The influence of national culture on organizational culture is mostly visible in: [Sikorski, 2003]

- the communication in the organization - meaning the level of openness and formality of this process, how extrovert it is, and whether it is possible to show emotions,

- leadership - especially the sources of power and the ways of exercising it, the proximity or distance in the hierarchy, the level of the employees’ participation in the decision-making process, the feeling of community,

- motivation - the pressure to achieve results, competition, the acceptance of uncertainty, the care for the quality of interpersonal relations, the evaluation of individuals and groups, providing safety,

- the organization model - especially the level of the standard-

- ization of work, processes and skills, structure, and ways of exercising control. 4. Organizational culture and humanitarian cooperation

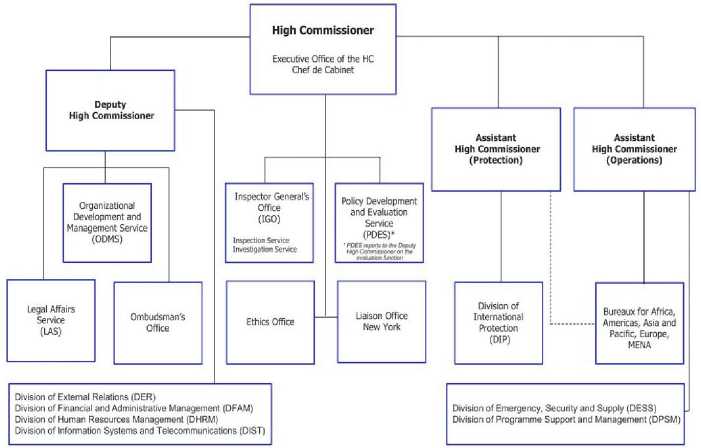

To show the importance of healthy and strong organizational culture, an example of an organizational structure of UNHCR is depicted in figure 5. $s it can be seen the organization has a complex structure. This type of organization is a global organization with a multitude of departments and regional offices. Every organization like UNHCR should be well managed and improved. To achieve so there should be established and fostered a culture that strengthens the bonds among employees both between departments and countries’ offices. Organizational culture helps employees better understand the aim organization is trying to achieve.

Figure 5. Executive direction and management ofUNHCR

The organizational culture among humanitarians should be assessed and changed if necessary. Changes that culture suffers can be positive or negative, so it is important to make sure that the changes are monitored and, if necessary, directed.

In order to deliver effective crisis response operations, an increasing number of individuals, groups, organizations, and 0urisdictions need to coordinate their actions. Thus, organizational culture could affect the way different actors perceive the interaction network influencing the process of seeking, trusting, and interpreting emergency information. [Prakash et al., 2020; Mutebi et al., 2020] To be able to establish and implement effective emergency management strategies it is required to perceive the differences among organizations and differences in understanding of the interaction networks. In an emergency, organizational culture affects the perception of humanitarians towards the interpretation of situations, tasks organizing, and interaction with others. Therefore, organizational culture plays a crucial role in the humanitarian supply chain and humanitarian operations by affecting the way different actors give an interpretation to the critical situation.

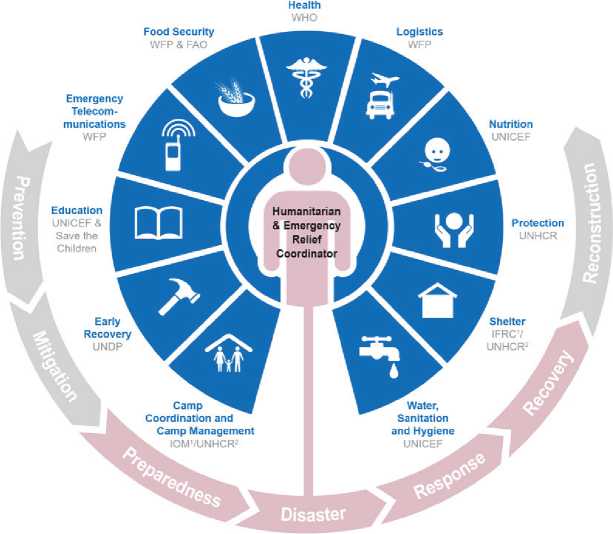

Figure 6. Cluster approach

To illustrate the complexity of the humanitarian sector The Cluster approach is presented. The foundations of the current international humanitarian coordination system were set by General $ssembly resolution 46/182 in December 1991. In 2005, a ma0or reform of humanitarian coordination, known as the Humanitarian Reform $genda, introduced a number of new elements to enhance predictability, accountability, and partnership. The Cluster $pproach was one of these new elements. Clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations, both UN and non-UN, in each of the main sectors of humanitarian action, e.g. water, health, and logistics. They are designated by the Inter-$gency Standing Committee (I$SC) and have clear responsibilities for coordination. Successful application of the cluster approach will depend on all humanitarian actors working as equal partners in all aspects of the humanitarian response: from assessment, analysis and planning to implementation, resource mobilization, and evaluation (I$SC, 2006). $s it can be seen in figure 6, the whole humanitarian cluster approach includes an abundance of organiza- tions. It depicts the complexity of humanitarian actions and emphasizes the need of establishing strong connections. Every organization has its own organizational structure and culture. This emphasizes the importance of values and beliefs uniformity, strong bonds among them, and the culture that unites all participants towards one goal, to save lives and belongings of beneficiaries.

The humanitarian coordination mechanism consists of more than 0ust "humanitarian" organizations, such as the donors, aid agencies, media agencies, NGOs, governments, militaries, logistics service providers, suppliers, and aid recipients. [Kovacs & Spens 2008;

5. Conclusion

Organizational culture is an important factor in humanitarian assistance and serves as the glue that sticks an organization together. Strong organizational culture can lower disaster risk and improve the overall performance of an organization. Many researchers have studied this field and a plethora of different approaches have emerged. Some of them are mentioned above and it could be seen that all of them show how important organizational culture is for an organization.

To improve response abilities when a disaster situation occurs, humanitarian organizations need well-organized employees and volunteers. 9olunteers, as an external workforce, are a very important part of humanitarian response, but they need to follow the rules established by the organization they do the volunteering work for. To follow those rules they need to be aware of the organizational culture, to foster a sense of belonging and the sense of the lives-saving 0ob. But sometimes the staff is not aware of

Список литературы The importance of organizational culture for humanitarian operations

- Aćimović, S., Mijušković, V., Marković, D., Milošević, N. (2020) The importance of post-disaster humanitarian aid distribution flows in humanitarian logistics. u: 33rd EBES International conference, Madrid, Spain, pp. 536-546

- Cameron, K.S., Quinn, R.E. (2006) Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass, Inc, Revised edition

- Chester, D.K., Duncan, A.M., Dibben, C.J. (2008) The importance of religion in shaping volcanic risk perception in Italy, with special reference to Vesuvius and Etna. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Vol. 172(3-4). pp. 216-228

- CHS Alliance, Group URD, The Sphere Project (2014) Core humanitarian standard on quality and accountability. Available at: https://cms. emergency. unhcr.org/ documents/11982/44705/The+Cor e+Humanitarian+Standard+on+ Quality+and+Accountability+%2 8HAP+International%2C+People +In+Aid+and+the+Sphere+Proi e ct%2

- Cohn, L., Macfarlane, S., Yanez, C., Imai, W. (1995) Risk perception: Differences between adolescents and adults. Health psychology, Vol. 14(3). pp. 217-222

- Hewitt, B. (2012) The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction: Culture, hazard and disaster. London, UK: Routledge

- Hilhorst, D., Schmiemann, N. (2002) Humanitarian principles and organizational culture: Everyday practice in Médecins sans Frontières-Holland. Development in Practice, Vol. 12(3). pp.490-500

- Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D.D., Sanders, G. (1990) Measuring organizational cultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(2): 286-316

- IASC (2006) Guidance note on using the cluster approach to strengthen humanitarian response. Available at: https://interagencvstandingcom mittee.org/system/files/2021-03/Guidance%20Note%20on%20 Using%20the%20Cluster%20App roach%20to%20Strengthen%20H umanitarian% 20Response.pdf

- ICRC (1986) The fundamental principles of the international red cross and red crescent movement. Available at: https : //www.icrc.org/en/doc/resou rces/documents/red-crosscrescentmovement/fundamentalnrincinles-movement-1986-1Q31.htm

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2006) Guidance note on using the cluster approach to strengthen humanitarian response

- IOM IOM organizational structure. Available at: https://www.iom.int/organization al-structure

- Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K. (2012) Fundamentals of strategy. Edinburgh, UK: Pearson Education Limited, 2nd edition

- Johnson, K., Wahl, D., Thomalla, F. (2016) Addressing the cultural gap between humanitarian assistance and local responses to risk through a place-based approach. Project: SEI Asia Centre Research Cluster on Reducing Disaster Risk

- Kovacs, G., Spens, K. (2008) Northern lights in logistics and supply chain management: Humanitarian logistics revisited. Copenhagen, Denmark: CBS Press

- Kruks-Wisner, G. (2010) Seeking the local state: Gender, caste, and the pursuit of public services in post-tsunami India. World Development, Vol. 39(7). pp. 1143-1154

- Kwantes, C.T., Boglarsky, C.A. (2004) Do occupational groups vary in expressed organizational culture preferences: A study of six occupations in the United States. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management [Special Issue: Identifying Culture], Vol. 4. pp. 335-353

- Louis, M. (1985) An investigator's guide to workplace culture. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

- Martin, J., Siehl, C. (1983) Organizational culture and counterculture: An uneasy symbiosis. Organizational Dynamics, 12(2): 52-64

- Mutebi, H., Ntayi, J.M., Muhwezi, M., Munene, J.C. (2020) Self-organisation, adaptability, organisational networks and inter-organisational coordination: Empirical evidence from humanitarian organisations in Uganda. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 10(4): 447-483

- Oloruntoba, R., Gray, R. (2006) Humanitarian aid: An agile supply chain?. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 11(2). pp. 115-120

- Paradise, T.R. (2005) Perception of earthquake risk in Agadir, Morocco: A case study from a Muslim community. Environmental Hazards, 6(3): 167-180

- Pettigrew, A. (1979) On studying organizational cultures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 570-581

- Prakash, C., Besiou, M., Charan, P., Gupta, S. (2020) Organization theory in humanitarian operations: A review and suggested research agenda. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 10(2): 261-284

- Reis, F.A. (2018) Military logistics in natural disasters: The use of the NATO response force in assistance to the Pakistan earthquake relief efforts. Contexto Internacional, 40(1): 73-96

- Renn, O., Rohrmann, B. (2000) Cross-cultural risk perception: State and challenges. Boston, USA: Springer US, 211-233

- Righi, E., Lauriola, P., Ghinoi, A., Giovannetti, E., Soldati, M. (2021) Disaster risk reduction and interdisciplinary education and training. Progress in Disaster Science, Vol. 10. pp. 1-16

- Robbins, S.P., Coulter, M. (2005) Management. New Jersey, USA: Pearson Prentice Hall, 8th edition

- Robbins, S.P., Judge, T.A. (2012) Organizational behavior. New Jersey, USA: Pearson Prentice Hall

- Schein, E. (2004) Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, USA: Jossey-Bass, Inc, 3rd edition

- Schwartz, H., Davis, S.M. (1981) Matching corporate culture and business strategy. Organizational Dynamics, 10(1): 30-48

- Scott-Findlay, S., Estabrooks, C.A. (2006) Mapping the organizational culture research in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5): 498-513

- Sikorski, C. (2003) Zapami^tane z dziecinstwa: Szkice o kulturze organizacyjnej. Lodz, Poland: Wydawnictwo Wyzszej Szkoly Humanistyczno-Ekonomicznej

- Sphere Association (2018) The sphere handbook: Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. Geneva, Switzerland, 4th edition

- Szczepanska, K., Kosiorek, D. (2017) Factors influencing organizational culture. u: Scientific papers of Silesian university of technology. Organization and management series, pp. 457-468

- UN (2018) United Nations disaster assessment and coordination: UNDAC field handbook. UN, Available at: https://www.unocha.org/sites/uno cha/files/1823826E web pages.pdf

- UNHCR (2014) UNHCR global appeal 2014-2015: Operational support and management. Available at: https: //www.unhcr.org/publications/fundraising/528a0a380/unhcrglobal-appeal-2014-2015operational-supportmanagement.html

- UNOCHA What are humanitarian principles?. Available at: https: //www.unocha.org/sites/dm s/Documents/OOMhumanitarianprinciples.eng June12.pdf

- van Wassenhove, L.N. (2006) Humanitarian aid logistics: Supply chain management in high gear. Journal of the Operational Research Society, Vol. 57(5). pp. 475-489

- Walkup, M. (1997) Policy dysfunction in humanitarian organizations: The role of coping strategies, institutions, and organizational culture. Journal of Refugee Studies, Vol. 10 (1). pp. 37-60