The Jomon megalithic tradition in Japan: origins, features, and distribution

Автор: Tabarev A.V., Ivanova D.A., Nesterkina A.L., Solovieva E.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145341

IDR: 145145341 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.4.045-055

Текст обзорной статьи The Jomon megalithic tradition in Japan: origins, features, and distribution

Archaeological evidence suggests that there were at least three traditions of monumental structures in ancient times on the territory of the Japanese Archipelago. Two of them are later; one of these is associated with the dolmens of the Korean Peninsula and the distribution of the Yayoi culture on the greater part of the archipelago (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD), and the second is associated with the “period of burial mounds” (“Kofun-jidai”, 3rd–6th centuries AD). The third, more ancient and mysterious tradition, is represented by sites of the Jomon period (13,800-2300 BP). According to the variety of forms, monumentality, amount of materials used, and number of builders, as well as time and energy spent on the construction works, this tradition is by no means inferior to the later traditions on the Japanese archipelago. Moreover, from a global perspective, the Jomon tradition is yet another confirmation of the complexity and sophistication of ritual practices in the societies of hunters, gatherers, and fishermen who were not associated with a producing economy. The followers of those ritual practices actively experimented with materials (stone, soil, wood, or shells) for creating monumental structures, enhanced the visual effect by incorporating their complexes into the landscape, and

carried out regular “maintenance” of ritual objects intended for long-term use. The megaliths (stone structures) are only one type of monumental structure, but they are the best preserved and most informative in archaeological terms.

The very first European archaeologists who studied monuments of different periods, showed interest in monumental structures on the Japanese islands (Morse, 1880); there are articles and sections of books on individual complexes with “stone circles” and “sundials”, but comprehensive studies of this phenomenon have not yet been made in the European languages. In Russian archaeology, detailed research of the megalithic traditions in the ancient cultures of the Japanese archipelago is just beginning (Gnezdilova, 2015; Ivanova, 2015a; Ivanova, Tabarev, 2015). This article makes an overview of the main types of complexes, their distribution, and chronology. The historiography of the problem and discussion of the purposes of sites with monumental structures would require a separate study. Nevertheless, interesting parallels with the Final Paleolithic cultures of the Russian Far East (Primorye) will be identified already in this article, and a hypothesis on the origins of the early tradition will be proposed.

The Jomon megalithic tradition: distribution and main types of complexes

There is no single classification of the monumental structures of the Jomon period. An overview can be carried out according to various principles: time (from the earliest to the latest), territories (Kyushu, Honshu, Hokkaido), type (circles, alignments, clusters, pilings, etc.), size, presence or absence of accompanying burials, location outside settlements or on their territory, main building material (stone, wood, earth, or shells), etc.

The earliest versions of monumental structures are those in the form of stones placed in a row. For example, such clusters of stones have been found at the sites of the Early Jomon period (about 8000 BP) of Setaura (Kumamoto Prefecture, southern Kyushu) and Yamanokami (Nagano Prefecture, Chubu region) (Fig. 1). The former case is a cluster of rectangular shape measuring 21 m along the W–E line and 7 m along the N–S line. The latter case is a U-shaped alignment with the sizes of 11 and 9 m respectively, and with its open side facing west in the direction of Mount Gaki (the Hida Mountains, the Northern Japanese Alps). Numerous stone tools, represented mainly by polished points with concave bases, have been found at both sites. In addition to stone clusters, the complexes include semidugouts, hearth structures, and earth pits (Daikuhara Yutaka, 2013).

The Early Jomon sites (6500 BP) include the Akyu site (Hara village, Suwa District, Nagano Prefecture) covering an area of 55,000 m2. According to Japanese archaeologists, the earliest parts of the site are “stone circles” (see below) of large and small stones (over 100,000) arranged in two rows. The diameter of the outer circle is 120 m; the diameter of the inner circle is 90 m. A “central area” measuring 30 × 30 m is located inside the circles. Traces of a structure of 24 large (the largest height was about 1.2 m) and small stones, which were vertically set, and eight flat slabs of andesite were found there. Over 700 pits (presumably burials) of oval shape measuring 1 × 2 m in size and up to 0.3 m in depth were discovered under the clusters. Stone pillars were directed to the east towards Mount Tateshina (the Yatsugatake Mountains). In addition to the clusters of stones, holes from vertically erected posts have been found. These holes are the traces of 11 rectangular structures with sizes varying from 4.7 × 4.3 to 7.3 × 6.8 m. The number of holes ranges from 4 to 27; their depth reaches 1.5 m. These objects have been dated to the first half of the Early Jomon period. Traces of dwellings including over 50 semi-dugouts and eight groups of holes from posts (probably traces of pile foundations) were found within a radius of 50–100 m from the burial ground. The remains of the settlement go back to the beginning-middle of the Early Jomon period (Akyu iseki..., 1978: 26-30).

The earliest structures belonging to the variant with “vertically erected wooden posts” appear at the Akyujiri site (the city of Chino, Nagano Prefecture), which is dated to the first half of the Early Jomon period (6500 BP). The total area of the complex is over 11,000 m². The remains

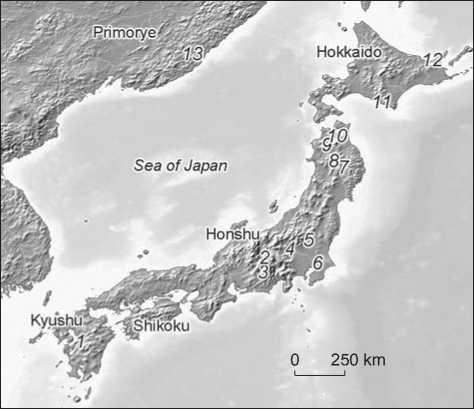

Fig. 1 . Main sites mentioned in this article.

1 - Setaura; 2 - Akyujiri; 3 - Yamanokami; 4 - Nomura; 5 - Terano Higashi; 6 - Kasori; 7 - Goshono; 8 - Oyu; 9 - Sannai Maruyama;

10 – Komakino; 11 – Goten’yama; 12 – Shuen; 13 – Ustinovka-4, Suvorovo-4, Bogopol-4.

of 39 dwelling pits of various shapes (round, oval, square, and rectangular with rounded corners) with an average size of 5.5 × 4.5 m have been discovered at the site. Traces (holes from posts) of 20 structures of square and rectangular shape (with rounded corners) of various size and various amounts of posts, ranging from small (2.2 × 2.1 m, eight holes from posts) to large (5.9 × 6 m, 18 holes), have been found. The depth of the holes varied from 0.5 to 1.5 m; the average diameter was 0.9–1.2 m in the upper part and 0.5–0.7 m at the bottom. Fifty seven small earth pits of oval shape, several pits with stone lining, and individual clusters of stones have also been found at the site. The remains of the dwellings and the earth pits belong to the range from the second half of the Early Jomon to the beginning of the Middle Jomon period (Akyujiri iseki…, 1993: 55–103).

The construction of “stone circles” (one of the most spectacular types of monumental structures) began at least from the end of the Middle Jomon period (4100-4000 BP), reached the largest scale in the first half of the Late Jomon period (4000-3 700 BP), and ended in the Final Jomon period (3000-2300 BP). Currently, over 100 complexes are known. They have been discovered on the island of Hokkaido and in the northeast of the island of Honshu, mainly in the Aomori, Iwate, and Akita Prefectures. There is also some evidence of finding “stone circles” in Central Japan (Kanto and Chubu regions). On the southern islands of the archipelago (Kyushu and Ryukyu), during the Late-Final Jomon period (4500–2800 BP), such structures are absent; burials with various types of stonework (stone piles, various types of dolmens) are typical of this area (Nakamura Kenji, 2007).

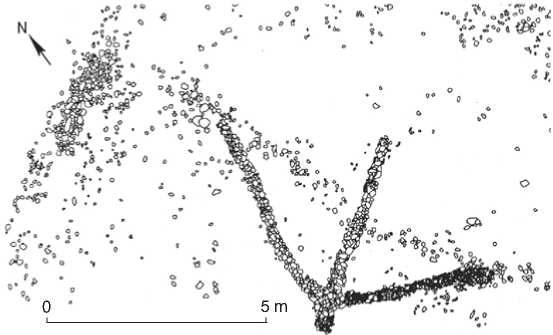

Small (not more than 3–5 m) scattered groups of stones piled together have been observed at many sites of the island of Hokkaido and in the Tohoku region from the late Middle to the first half of the Late Jomon period (about 41003700 BP). Stone clusters of rounded shape in the form of an arc, which resemble mountains, or in the form of a “strained bow” have been found. Oval earth pits up to 1 m deep were located under individual groups of stones; human remains have not been found in the pits. In Japanese literature, such objects are defined as immediate predecessors of the monumental “stone circles” of the Late Jomon period. These monuments include the sites of Yubunezawa II, Kabayama, Hatten, Simizuyashiki II, Tateishino I, and the Monzen shell midden site, located in the Iwate Prefecture (Jomon no suton sakuru..., 2012: 7–21) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 . Monuments with stone alignments at Yubunezawa II ( 1 ) and Monzen ( 2 ).

A large number of complexes with early “stone circles” are known on the territory of the Gunma Prefecture: Nomura site (the city of Annaka), Hisamori site (the town of Nakanojo), Tazuno Nakahara site (the city of Tomioka), Higashihara Teranishi site (the city of Fujioka), as well as Achiya Daira site (the town of Asahi) and Dojitte site (the town of Tsunan) in the Niigata Prefecture. The Nomura site, located in the northern part of the city of Annaka (southwestern district of the Gunma Prefecture), consists of a settlement of a concentric type (first half of the Early Jomon period) and a large “stone circle” (second half of the Middle Jomon period). The circle is of rectangular shape with rounded corners; its size is 36 m along the W–E line and 30 m along the N–S line. The northern half of the “stone circle” has a finished appearance, while the southern half looks incomplete or partially damaged. Flat graves were found nearby, and a group of dwellings with stone-paved floors was located on the northern side. Apparently, when choosing a place for constructing “stone circles”, attention was paid to the connection of the landscape (mountains) and astronomical events (summer and winter solstice, spring and autumn equinox). For example, at the Nomura site, one may observe the sunset over Mount Myogi during the winter solstice, and at the Tazuno Nakahara site (the city of Tomioka, southern part of the Gunma Prefecture) over Mount Asama during the summer solstice. Many scholars have also noted that specific features of the stone arrangement might have had a certain visual effect. Thus, if you look at the rectangular structure at the Nomura site from a hill, its shape looks absolutely round (Daikuhara Yutaka, 2005, 2013: 42; Hatsuyama Takayuki, 2005).

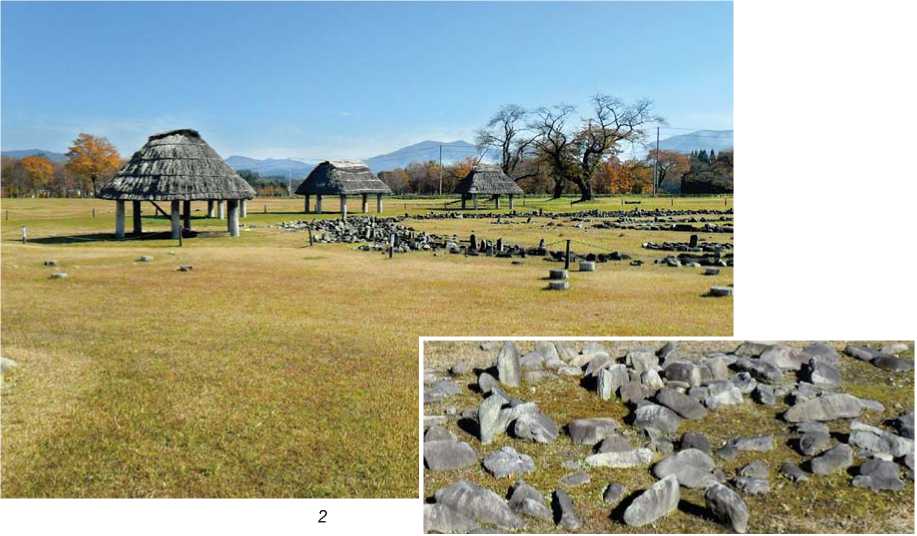

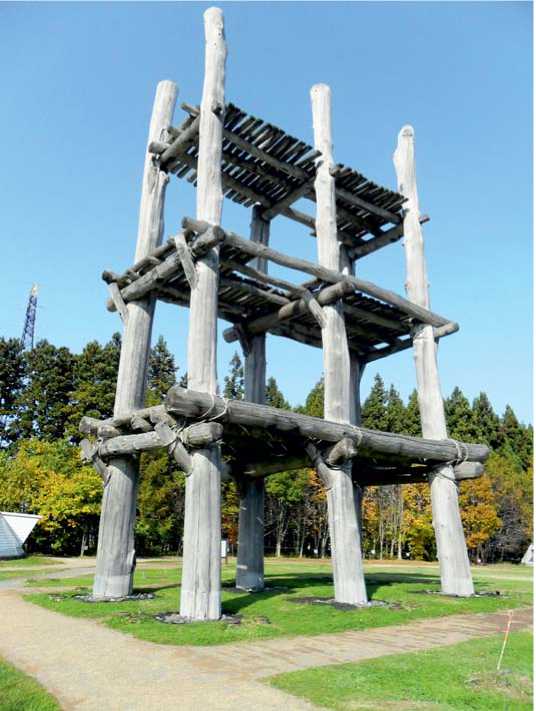

Noteworthy are also the monumental complexes located inside large settlements, for example, the Goshono site in the Iwate Prefecture on the island of Honshu. This site is dated to 4500–4000 BP and belongs to the middle and the second half of the Middle Jomon period. Seven clusters of stones of various shapes and sizes were located in its central part. They are arranged in a circle with a diameter of 30–40 m. The clusters are of oval shape; they range in size from 1.0 to 2.5 m. Oval earth pits measuring 0.5 × 1.0 and 2 × 3 m, which might have been graves, have been found around them. About 650 holes from posts have been discovered around the perimeter of the complex. They form several groups located along the perimeter of a rectangular area. Currently, this part of the monument is reconstructed in the form of open supporting structures with a canopy on six pillars (Takada Kazunori, 2005: 32–46; Ivanova, 2015b).

“Stone circles” of the Late Jomon period differ from the structures of the early stage by their scale and a clearly articulated oval or rectangular shape measuring 30 to 50 m. Beginning in the first half of the Late Jomon period, arc-shaped clusters started to appear in the Kanto and Chubu regions. Thus, in the Gunma Prefecture, such objects have been found at the Tazuno Nakahara site (the city of Tomioka), Yokokabe Nakamura site (the town of Naganohara), and Karasawa site (the city of Shibukawa). In some cases, under the arc-shaped clusters, flat graves were located.

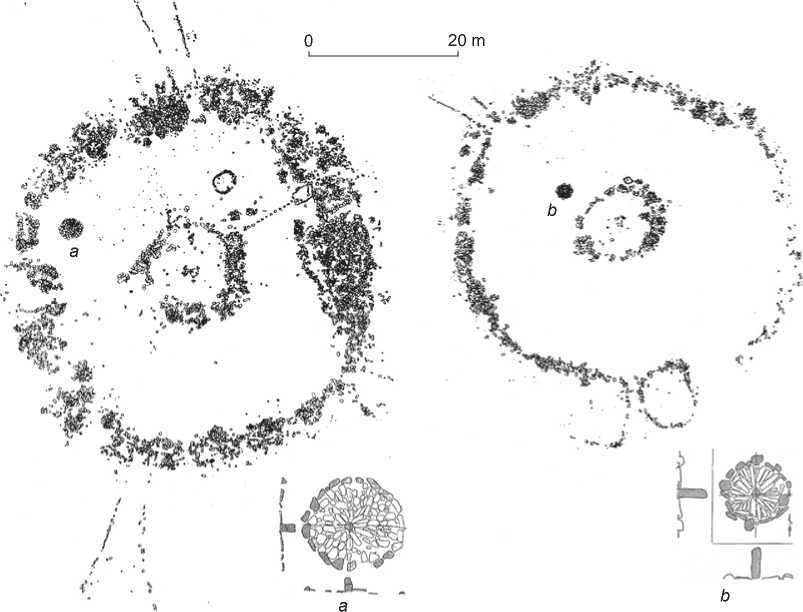

The Oyu complex of the Late Jomon period, located in the Akita Prefecture on the island of Honshu, stands out from all sites with “stone circles” and alignments. The complex consists of two separate structures, the Manza (lit. ‘ten thousand places’) and Nonakado (‘temple in the middle of the field’), each consisting of two stone circles. The former structure is made of over 105 stones; the diameter of the outer circle is 52 m; the diameter of the inner circle is 16 m. The Nonakado structure amounts to over 55 stones; the diameter of the outer circle is 44 m; the diameter of the inner circle is 14 m. In the northwestern parts of both structures, small complexes are located, called “the sundials” (Fig. 3, 1): elongated large stones are radially placed around a vertical stone pillar, and the whole structure is enclosed in a ring of stones. According to S. Kawaguchi (1956), the Oyu complex was based on the beliefs of the Jomon population concerning the motion of the celestial bodies. If we draw a straight line between the “sundials” of Manza and Nonakado, it will coincide with the line of the sunset during the summer solstice. Eight pile-supported structures were reconstructed around the Manza “stone circle” (Fig. 3, 2); several burials were excavated, and a sophisticated object consisting of over 50 wooden posts arranged in a circle was found in the western part of the Oyu complex (Jomon no suton sakuru, 2012: 22–31; Kobayashi, 2004: 180–181).

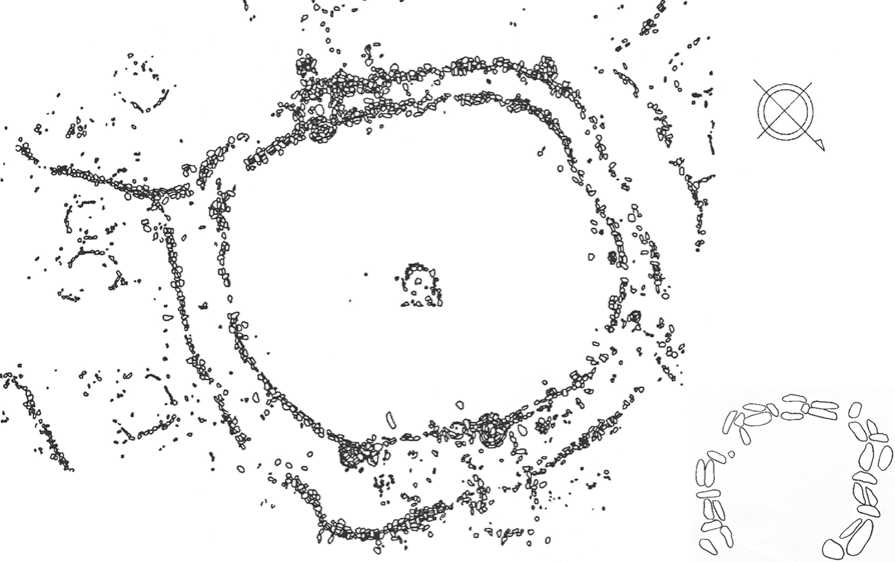

An even more sophisticated complex covering about 9700 m 2 and going back to the Late Jomon period, was investigated at the Komakino site (Aomori Prefecture) (Endo Masao, Kodama Daisei, 2005). It consists of three “stone circles”: central (2.5 m), inner (29 m), and outer (35 m) (Fig. 4, 1 ). The central circle is composed of large blocks with a total weight reaching 500 kg, and several dozens of small blocks. The inner and outer circles are laid out in two layers in a special order according to the pattern, “one large stone set vertically and from three to six set horizontally”, which has received the name of the “Komakino style”. It is notable that a similar pattern in the simplified form “1 + 2” was also used for creating small circles (Fig. 4, 2 ). The placement of stones was preceded by a large-scale digging of soil (over 300 m3) and its layered redistribution. All stone material (over 2500 boulders) was delivered from the banks of the Arakawa River, which is located ca 500 m from the site. Small ring-shaped, arc-shaped, and sub-rectangular complexes were found around the outer ring and inside the circles. These complexes are the markers of burials (in pits, jars), elements of household pits, “paths”, and dwelling structures. It may be assumed that burials in the inner ring (in ceramic vessels) might have belonged to the representatives of the tribal elite (chiefs, shamans) (Kodama, 2003: 258; Ivanova, Popov, Tabarev, 2013). In the Aomori Prefecture, several small stone structures dating to the Late Jomon period have been found, including the Oishidai site and complexes in the city of Hachinohe and the town of Sannohe (Jomon no suton sakuru, 2012: 53-65).

In the Final Jomon period, a noticeable decline in construction of monumental structures is observed. The most impressive complexes of that time include the Omori-Katsuyama site (Aomori Prefecture) and Tateishi site (Iwate Prefecture). The former represents

Й?®'^

Fig. 3 . The Oyu complex.

1 – general plan: а , b – the “sundial”; 2 – reconstruction of pile-supported structures; 3 – fragment of stone circle (photograph by D.A. Ivanova).

\ Wo 1

1 О 9

0 2 0 m 1 2

Fig. 4 . General plan ( 1 ) of the Komakino complex and fragment of ring stonework in the “Komakino style” ( 2 ).

a “stone circle” with a diameter of 48.5 m accompanied by 77 small clusters of stones. The latter complex consists of scattered stone alignments. In general, burial complexes with various identification signs (vertically set stones), stone boxes, and small piles of stones became common at this stage (Yamada Yasuhiro, 2007; Ivanova, 2012).

About 60 sites with “stone circles” and large clusters of stones going back to the Late-Final Jomon period are known from the territory of the island of Hokkaido. Complexes of the Late Jomon period are represented by circles and round and square stone clusters, which range in size from 5 to 40 m. These include the sites of Washinoki, Nishizakiyama, Yunosato V, and Kamui Kotan. Burial grounds with “stone circles” appear at two large sites of Goten’yama and Shuen. Both complexes consist of several “stone circles” with a diameter of 32 m and about 20 “stone rings” of oval or subrectangular shape ranging in size from 2.5 to 7.0 m inside the larger circles. A small barrow (from 0.6 × 0.8 to 1.3 × 3.3 m), lined with stones, was located inside each “stone ring”; a grave pit of oval or round shape, 1.5–2.0 m deep, was underneath the mound. There were 21 burials at the Shuen burial ground, and about a hundred burials at the Goten’yama burial ground (Fujimoto Hideo, 1971: 37–55; Vasilievsky, 1981: 96–104).

Sites with monumental earthen mounds, shell middens, and wooden structures

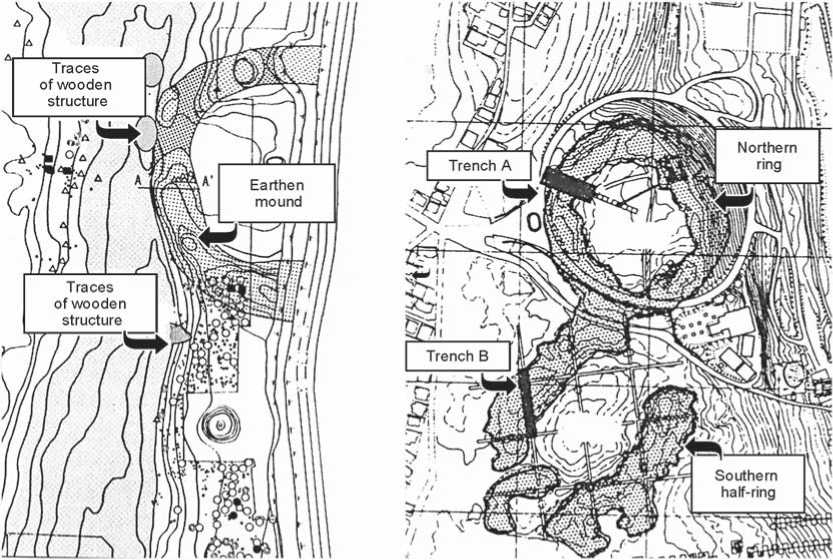

Stone was not the only building material for monumental structures. An example of a complex with a thick earthen mound is the Terano Higashi site, located in the southeastern part of the city of Oyama (the southern part of the Tochigi Prefecture), on the border with the city of Yuki (Ibaraki Prefecture). Archaeological objects from the Paleolithic to the Heian period were found on an area of 26 hectares on the right bank of the Togawa River, on the edge of a terrace rising 43 m above the sea level. The remains of a large settlement, represented by dwellings (127 dwelling pits), earth pits (over 900), and burial urns (95 jars) belong to the Middle Jomon period (4600–4000 BP). A large earthen mound was erected in the center of the site in the range from the first half of the Late Jomon period (3800 BP) to the first half of the Final Jomon period (2800 BP). The mound has the shape of a semicircle; its outer diameter is 165 m and the inner diameter is 100–110 m; the width of the mound varies from 15 to 30 m; the height ranges from 2.5 to 4.4 m. In its center, the remains of a platform of 18 × 14 m paved with stone have been found. The mound is constituted not by a single massif, but consists of four individual parts (northern, northwestern, western, and

100 m

0 100 m

Fig. 5 . The Terano Higashi earthen mound ( 1 ) and Kasori shell midden (after: (Kawashima, 2010)) ( 2 ).

southern). An artificial ditch 10–15 m wide with depth reaching 17 m in some places, adjoins the mound on the western side. Traces of 14 wooden “platforms” or containers for temporary storage of seafood have been found on the bottom of the ditch (Hatsuyama Takayuki, 2005) (Fig. 5, 1 ).

The Kasori site in the Chiba Prefecture is the most vivid example of a Jomon site where shell middens act as monumental structures (Fig. 5, 2 ). The largest shell midden in the world is located there, covering an area of over 13.4 hectares and reaching a height from 4 to 18 m. The midden consists of two parts: the northern ring (up to 130 m in diameter) dating to the Middle Jomon period, and the southern half-ring (over 170 m in diameter), which was made in the Late Jomon period.

Several large shell middens of ring or horseshoe shape, belonging to the Middle-Late Jomon period, such as Arayashiki (diameter 150 m, height up to 19 m), Horinouchi (about 200 m in diameter), and Takanekido (diameter of over 100 m, height up to 15 m), etc., have been discovered in the same area (the Tokyo Bay). According to some archaeologists, the increase in the amount of consumed seafood in the Late and Final Jomon period was caused not by the demographic situation, but by an intensification of ritual activities and regular performance of ceremonies accompanied by feasts

(Kawashima, 2010: 189–190). This is confirmed by numerous ritual objects (clay dogu figurines, amulets, elegantly decorated dishware) among the materials from the sites.

In the large dwelling complex of Sannai Maruyama (5050–3900 BP), which includes over 700 dwellings, a necropolis, earthen mounds, and several shell piles, a unique wooden structure (supposedly, an astronomical complex) has been found. This is a pile-supported structure on six supporting posts up to 1 m in diameter, with a height of approximately 20 m, and with three layers of platforms (Fig. 6) (Habu, 2004: 110–118; Ivanova, 2014). The situation with the Sannai Maruyama site is not unique. Rather, it confirms the general Eurasian trend: megaliths in many cases was preceded by wooden structures. The most famous example is the traces of massive wooden structures at the site where later Stonehenge was built in England (Darvill et al., 2012; Lawson, 1997).

Conclusion: in search of the origins of the Jomon megalithic tradition

As it has been already mentioned above, the earliest monumental structures (“stone rings”, alignments) on

Fig. 6 . Reconstruction of a layered structure, Sannai Maruyama (photograph by D.A. Ivanova).

the Japanese Archipelago appeared already in the Initial and Early Jomon period (8000-6500 BP). The origins of this tradition are rooted in even greater antiquity, the Late Paleolithic. The most important element in the majority of megalithic complexes are vertically placed stones or columns. Owing to the poor preservation of organic materials in acidic soils, it is difficult to trace wooden structures, but sufficiently large numbers of stone finds have been discovered. The earliest of them are the fragments of symbolic figurines sculpted from elongated pebbles from the sites of Iwate, Masugata, and Musashi dating from 20,000 to 16,000 BP. Some Japanese scholars believe that they can be even earlier, going back to 24,000–20,000 BP (Harunari, 1996).

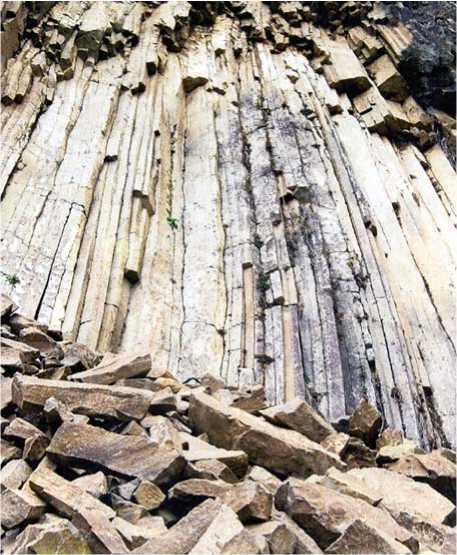

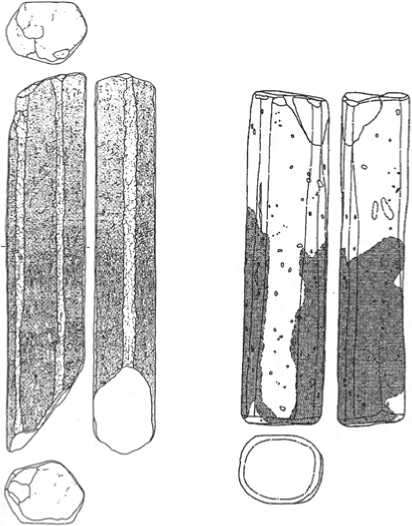

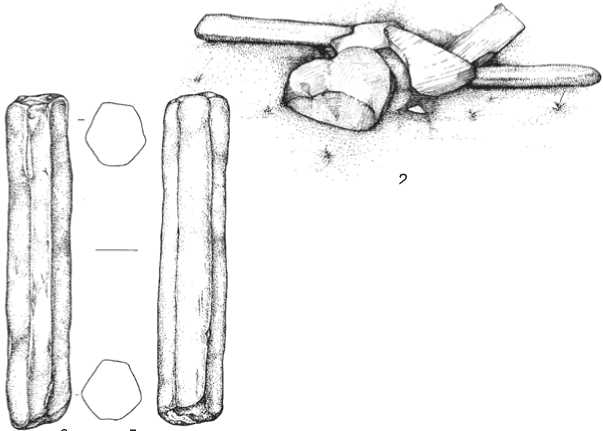

Large natural outcrops of columnar dacites are known on the island of Honshu (Gunma, Saitama, Nagano, and Niigata Prefectures), as well as on the island of Hokkaido (Fig. 7, 1). It is as if nature offered humans ready-made elements for ritual complexes and structures. For the first time, the use of fragments of dacite columnar joints with a hexagonal cross-section as vertical symbols was observed at the sites of the Mikoshiba culture (13,500– 11,500 BP), transitional from the Paleolithic to the Jomon period, seen in the Mikoshiba A and Karasawa B sites (Mikoshiba Site…, 2008: 22– 25; Tabarev, 2011) (Fig. 7, 2, 3). The tradition of their use continued into the Jomon period; dacite hexahedrons of various lengths (from 5–10 to 100 cm and more) have been found in dwelling complexes, graves, and in small clusters of stones, which constituted circles and alignments (Jomonjin no ishigami..., 2010: 5-10; Sasaki Akira, 1989) (Fig. 7, 4, 5).

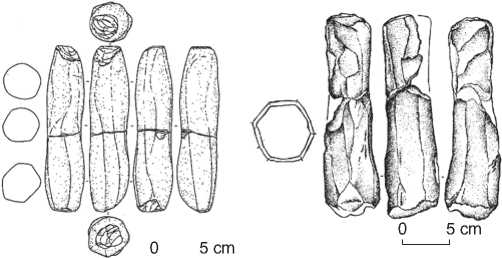

The early tradition of vertical stone symbols appeared not only on the islands of the Japanese Archipelago; its manifestations in the Final Paleolithic have been observed in the coastal part of the Russian Far East (15,000–12,000 BP). This is evidenced by complexes with hexahedrons and bifaces at the sites of the Ustinovka culture in Primorye. The first description of such a complex was published in 1997 (Dyakov, 1997). The complex was discovered at the Ustinovka-4 site. It consisted of seven bifacial objects placed on a small (0.3 × 0.3 m) area; one more biface (the largest) was vertically set on a small elevation in the center. In 1999, during the excavation of the Suvorovo-4 site, a 24.5 cm long fragment of a columnar joint of dacite-porphyry with hexagonal crosssection was found at its highest point (Fig. 8, 1 ). A date of 15,900 ± 120 BP (AA-36626) was obtained from the charcoal accompanying this complex. In 2002, at the Bogopol-4 site, a complex with a stone hexahedron (39.8 cm long) accompanied by three rounded pebbles and two elongated fragments of stone was found (Fig. 8, 2 ). A bifacial knife was discovered underneath the hexahedron at a depth of 11 cm (Krupyanko, Tabarev, 2001: 8–9; 2013; Tabarev, 2011). Natural outcrops of columnar dacites with hexagonal cross-section are known in Primorye and on the Korean peninsula, so there is no reason to speak about any borrowings between the regions.

Thus, the Jomon megalithic tradition is an outstanding landmark of an entire era in the ancient history of the Japanese Archipelago. These spectacular monuments reflect sophisticated ritual practices of hunters, gatherers, and fishers, evolving over 10,000 years. At the same time, this phenomenon is one of the elements in a sophisticated mosaic of megalithic traditions which existed in the ancient cultures of the continental, coastal, and island parts of East and Southeast Asia. The search for the parallels and possible links between these traditions, and their analysis seem to offer interesting perspectives for research, which may lead to unexpected discoveries.

0 20 cm

0 20 cm

Fig. 7 . Dacite hexahedrons.

1 – natural outcrops of columnar dacites with hexagonal cross-section, Gunma Prefecture; 2 – Mikoshiba A; 3 – Karasawa B; 4 , 5 - Tama New Town, Late Jomon period.

а

Fig. 8 . Complexes with hexahedrons in the Final Paleolithic of Primorye (drawings by Y.V. Tabareva).

1 – Suvorovo-4 site: a – general view of the complex, b – dacite hexahedron; 2 – Bogopol-4.

b

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 14-50-00036). The authors are sincerely grateful to Professor Yoshitaka Kanomata (Tohoku University, Japan) for the opportunity to visit archaeological sites in the Aomori, Akita, and Iwate Prefectures, and Y.V. Tabareva for preparing the illustrations for this article.