The morphology of bronze and early iron age Celts from Siberia

Автор: Nenakhov D.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145284

IDR: 145145284 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2016.44.4.067-075

Текст статьи The morphology of bronze and early iron age Celts from Siberia

Each new Turkic runic inscription from South Siberia and Central Asia is an important scientific discovery. To date, the corpus of runic inscriptions from the Altai consists of about ninety concise texts and lines (Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012: 16). The overwhelming majority of these inscriptions are epitaphs dedicated to relatives or respected people, and only a small number of inscriptions contain references to political events, the highest titles of the holders of state power, or the names of tribes. Some runic and one Uyghur inscription from the area of

Urkosh, which have recently been discovered in Central Altai, represent a striking example of such epistolary monuments (Tugusheva, Klyashtorny, Kubarev, 2014). They mention the titles of the highest holders of state power or the tribal leaders ( erkin , tengriken ); and the inscription in Uyghur script was probably devoted to erkin , the leader of the tribe and the subject to one of the Qïrqïz Qaghans (Ibid.: 92).

In 1991, V.D. Kubarev carried out extensive works on copying and photographing drawings at the site of Kalbak-Tash II. In the field season of 2015, the Chuya team of the North-Asian Joint Expedition of IAE SB RAS continued research at that site with the purpose of copying Early Medieval graffiti, those which were already known and those discovered for the first time (Kubarev G.V., 2015).

The petroglyphic complex of Kalbak-Tash II is located in the Ongudaysky District of the Republic of Altai, on the right bank of the Chuya River, 1–1.5 km from its confluence with the Katun River and 10 km from the petroglyphic site of Kalbak-Tash I (Fig. 1)—the reference site of the Altai rock art (Kubarev V.D., 2011). Moreover, this site is the largest center of runic rockinscriptions from the Old Turkic period—not only in the territory of the Republic of Altai, but in the whole of Russia (Ibid.: 9, App. IV; Tybykova, Nevskaya, Erdal, 2012: 4, 69). In total, 31 Old Turkic runic inscriptions have been found at Kalbak-Tash I since the early 1980s. They have been studied by such specialists in Turkic studies as V.M. Nadelyaev, D.D. Vasiliev, L.R. Kyzlasov, M. Erdal, L.N. Tybykova, I.A. Nevskaya, and others. It is surprising, then, that until now, not a single runic inscription had been found at the petroglyphic site of Kalbak-Tash II, which is located relatively closely to Kalbak-Tash I. Thus, the first such discovery at that site is of great importance for Old Turkic epigraphy.

The runic inscription was found on the residual outcrop that stretched as a rock-ridge across the valley of the Chuya River, north of the Chuya Highway, in the area of Chuy-Oozy (Fig. 2). The rock-ridge forms large rock ledges of almost rectangular shapes. A short runic inscription was distinctly engraved on a vertical surface of one of the ledges facing east (Fig. 3). Shale rock-surface in this location is overgrown with moss and lichen. The last characters at the bottom line of the inscription overlay an earlier engraved representation of an animal.

Transliteration, translation, and commentary by M. Erdal*

The inscription clearly runs from top to bottom, and consists of seven characters: two on the top, then (after a small gap) two more very distinct and three barely legible characters, almost merging with each other (Fig. 3, 4). No additional characters are visible at the bottom, on the part damaged by incision, although apparently the vertical frame-line continues in that direction. The majority of runic rock inscriptions from Southern Siberia are vertical, since they represent epitaphs commemorating the death of a respected person or a relative.

Fig. 1. Location of the petroglyphic site of Kalbak-Tash II.

I propose the following transliteration of the inscription: t 1 1 2 A z g2 i c c

Notes on the individual characters. If we consider the first character a variant of the usual shape of t1, this character would have been turned clockwise by 90°. Another possible reading would be the lower half of a horizontally inverted d1; the area near this character is damaged, which makes it possible to interpret it in this way. However, the sequence d1 l2 does not seem to make sense if the inscription is to be read as Turkic.

The fourth character is far from having the canonical shape of character z, but I cannot interpret it otherwise (Vasiliev, 1983a: 142). The rightward hook in the lower part of the character excludes the reading of the character as k2.

The fifth character should have been normally read as s2, since the vertical line is clearly visible here; but that would leave without explanation a small but clear horizontal line to the left of the character. The line should be assigned to this character and not to the sixth character, to read the character as g2, although I personally see on all photographs that it is linked to the sixth and not to the fifth character. According to the drawing made by G.V. Kubarev, this line is linked with both characters (Fig. 4, a ); but the interpretation of individual characters links it only with the fifth character (Fig. 4, b ). I am following Kubarev in this matter, since I cannot suggest any paleographic or semantic interpretation of the inscription with a different reading of these characters.

^'Wfj

Fig. 3 . Runic inscription on the rock of Kalbak-Tash II.

Fig. 2. General view of the mountain-range in the area of Chuy-Oozy where the runic inscription was found.

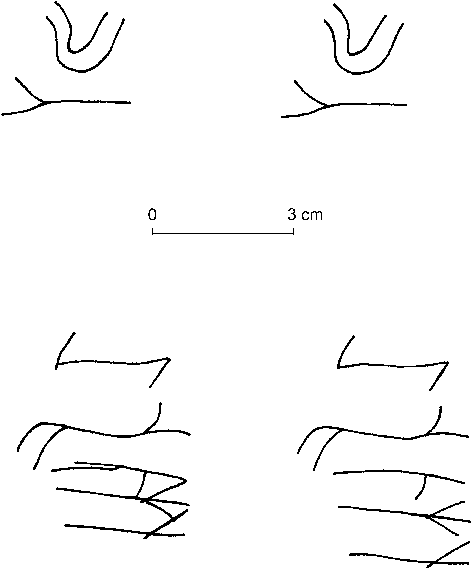

Fig. 4 . Drawing of the runic inscription ( a ), and the interpretation of its individual characters ( b ).

The sixth and seventh characters can be confidently interpreted as i c (that is, i before or after c) and c (with a rare but attested asymmetric shape).

I tentatively propose the following reading and translation:

(A)t (e)l Az (a)qci, (a)C!

“The Horse tribe. Hunters of the Az (tribe), open (the way)!”

Notes on the reading of the inscription. The At el tribe is mentioned in line A1 of the inscription E-68 (Erdal, 2002: 65–68)*. This line corresponds to the line XI from the monographic study of D.D. Vasiliev (1983b: 36). My edition is based on the unpublished work of K. Wulff (the assistant of W. Thomsen), who in the early 1920s used the estampages of the Asiatic Museum in Leningrad**, whereas Vasiliev used the first publication of the inscription (Nasilov, 1963)***. According to lines 7 and 13, the woman commemorated in that epitaph**** lived in the town of At balïq. But until now, neither At el nor At balïq were attested elsewhere. Now we have a second instance when this tribe is mentioned.

The inscription E-68 was discovered in the Republic of Tuva, south-west of Kyzyl and west of the Elegest River valley. In the early 8th century, this was the area where the Az lived, to the west of the Cik and to the east of the Qïrqïz (Golden, 1992: 142). The inscriptions dedicated to Köl Tegin (line E-20) and Bilgä Qaghan (line E-17) inform us that the Old Turks defeated the Az, killed their Qaghan, and reorganized the Az and Qïrqïz tribes. Line N3 of the inscription of Köl Tegin mentions the disappearance of the Az ( yoq boltï ). It seems that the third word in our inscription from Kalbak-Tash II also refers to the Az. If they really were destroyed by the Old Turks in the early 8th century, the inscription must have been earlier than the Orkhon runic monuments.

In spite of the Old Uyghur spelling and form of the word in Mongolian and Turkic languages of Siberia (the latter borrowed it back from the Mongolian languages), the Old Turkic word for “hunter” is not ayci but ayci (Erdal, 1991: 435–436; Röhrborn, 1998: 384). The word ay and its derivatives were spelled exactly in this way in Irq Bitig (“The Book of Omens”). A number of runic inscriptions from Southern Siberia have two completely different characters for g1 and g2, including the epitaph E-68. The inscription E-68 uses the character g2, but we cannot be sure that this guarantees a frontal consonant, since we cannot know to which spelling tradition this short runic inscription might have belonged.

The character i c may represent both the sound sequences ic and ci , but the latter sequence contradicts the classical spelling rule of the Orkhon inscriptions to leave the vowels at the ends of words unexpressed. The spelling rules in Southern Siberia could have been not as strict; and moreover, there is no other way to make sense of the inscription.

The word ac in the inscription is the imperative form of the verb “open”, but it also has numerous metaphorical meanings such as “conquer” (in line 28 of the Toñuquq inscription, combined with the word “spear” in the instrumental case, that is, “by the spear”), “initiate”, and “develop”.

History of research on the Az using written, archaeological, and ethnographic sources

Before analysis of the data on the Az contained in the runic written monuments, we should note that in spite of rendering the same general meaning, translations of the same Orkhon texts may differ significantly in detail, which affects their interpretation. As far as the much smaller runic inscriptions from Tuva and the Minusinsk Basin are concerned, their translations by various scholars sometimes show radical differences. In the following, I will try to list all cases when the Az may have been mentioned in the runic texts, at the same time indicating that in the translations of other scholars some of the inscriptions may not contain the name az . In my conclusions, I will primarily rely on the texts that are the least debated among specialists.

The Orkhon runic texts have been translated by many scholars including W. Thomsen, V.V. Radlov, P.M. Melioransky, S.E. Malov, K. Orkun,A.S.Amanzholov, K. Sartkozhauly, M. Zholdasbekov, and others. Radlov alone published them four times, each time providing some new revisions. It is thus not surprising that in many aspects the translations differ markedly from each other, and contain controversial expressions. This applies in full to the key phrases in the Orkhon texts, which mention the Az tribe. It should be noted that the word az has several meanings in the Old Turkic language: 1) little, few; 2) desire, greed; 3) the Az (ethnic name); and 4) or (conjunction, a part of speech) (Drevnetyurkskiy slovar, 1969: 71–72).

The Az tribe is mentioned in the three largest Orkhon texts: the inscriptions dedicated to Köl Tegin,

Bilgä Qaghan, and Toñuquq*. The first two inscriptions describe the military campaigns of the Turks against the Az. In the period of the Second Eastern Turkic Khaganate, the Tugyu Turks campaigned three times against the Az, conquering the territory of the Altai-Sayan. In 709, they conquered the Az together with the Cik, “Having crossed the Kem, I moved with my army against the Cik people, fought at Orpen, and defeated their army. I captured… and subjugated… the Az” (Malov, 1959: 20). In 710–711, in the Battle of Bolchu (Urungu River), the Turks defeated the Az detachment headed by the Elteber as a part of the Turgesh army (Malov, 1951: 41). Finally, in 715, the Turks defeated the Az in the Battle near Lake Karaköl in Western Tuva, “The Az have become the enemy to us. We fought near Karaköl (‘Black Lake’)… he threw himself into attack, grabbed the Elteber of the Az; the Az then perished” (Ibid.: 42). The text dedicated to Toñuquq and describing the campaign of the Old Turks against the Qïrqïz mentions “the land of the Az”, the tribe of the steppe Az, and a guide from that tribe (Ibid.: 67).

In the notes to the translation of the runic inscription from Kalbak-Tash II, M. Erdal mentions the Qaghan of the Az who was killed by the Turks. From the very beginning, scholars translated and interpreted this fragment of the text dedicated to Köl Tegin in various ways. The translation of Radlov and Melioransky is markedly different from other translations; thus it seems useful to cite it in full: “Khan [Qaghan – G.K.] of the Turgeshes was my Turk, my subject (or out of my people). Since from not understanding (his good), he was found guilty before us, the Khan (himself) died (was killed); his Buyuruqs and Begs all died; the people who held his side suffered distress. So (this) land (lit. ‘earth and water’), which was in the power of our ancestors, would not be (remain) without a ruler, we established the Az people**… There was Bars Beg; we gave him here (at that time) the title of Khan, gave him my younger sister, the Princess (as wife). He was guilty (before us), (therefore) he died, and his people became slave-girls and slaves. So the Kogmen land (land and water) would not remain without a ruler, I established the Az-Qïrqïz people (in the same way)” (Radlov, Melioransky, 1897: 21–22). However, only two years later, Melioransky came to the conclusion that the word “az” here should be translated as “not numerous” (1899: 68–69); and in the comments to the translation he suggested that it should be interpreted not literally, but as a defeated, scattered people (the Turgeshes and the Qïrqïz) who experienced a temporary decline (Ibid.: 112). Such an interpretation seems to be the most convincing; this fragment of text dedicated to Köl Tegin does not speak about the Az. Otherwise, its context becomes difficult to understand: why the army of one people was destroyed, but the Turks “established” a completely different tribe (and gave them a Qaghan). Subsequently, the interpretation of Melioransky was followed by Malov and Sartkozhauly who translated the word az here not as an ethnic name, but as an adjective: “small-numbered (or Az) people”, “small-numbered (that is, those who experienced decline) Qïrqïz people” (Malov, 1951: 38–39), “small nation”, “small-numbered Qïrqïz people” (Zholdasbekov, Sartkozhauly, 2006: 187).

The interpretation of this passage did not cause any particular discussion in the works of the Soviet and Russian scholars. According to them, Bars Beg was first appointed as a Qaghan of the Qïrqïz by the Turks, was given the princess (the younger sister of Qaghan) in marriage, and was subsequently killed by the Turks (Klyashtorny, 1976; Butanaev, Hudiakov, 2000: 67–68; and others).

The defeat of the Az in 715 did not lead to their physical disappearance, but rather implied their loss of independence. According to the translation by S.G. Klyashtorny, in about 753 (the time when the Terkhin monument with a runic inscription was created), seventeen Az Buyuruqs acting as representatives of their tribe, and “the Az Shipa Tai Sengun and his people”, were present during the setting of the monument of Uyghur Eletmish Bilgä Qaghan in Khangai (2010: 43). The inscription from Mogoyn Shine Usu in Mongolia mentions “a person from the Az people” who was sent as a spy to the land of the Qïrqïz. These events correspond to 752, the Uyghur campaign against the Cik in Tuva (Ibid.: 63). Thus, one could argue that the Az continued to live in their territories after the defeat by the Old Turks in 715; and after the disappearance of the Old Turks from the political landscape in 742, for probably the entire 8th century and possibly even later.

According to B.B. Mongush, the ethnic name az appears in the Khemchik-Chergaky runic text of the Qïrqïz period (E-41) (2013: 147). In the translation by D.D. Vasiliev, the epitaphs from the site of Bayan-Kol (E-100) in Central Tuva (right bank of the Ulug-Khem) mention “Alty-az” (“six Az people” or “six-partite Az people”) (1976). The runic inscription on the stele from the Abakan River (E-48) mentions “Aza tutuk” (Malov, 1952: 95–96). However, none of the above-mentioned inscriptions from the territory of Tuva and Khakassia contains the name az in the translations performed by I.V. Kormushin (1997: 44–60, 247–252; 2008: 41–57), which should be accepted considering Kormushin’s personal familiarity with the monuments and the thorough manner of his research on them. Apparently, these inscriptions cannot be used for studying the history and boundaries of the Az territories.

The literature in Russian on the history, archaeology, and ethnography of Southern Siberia pays significant attention to the Az tribe. The studies primarily rely on the references to the tribe in the Turkic runic monuments (inscriptions dedicated to Bilgä Qaghan, Köl Tegin, Toñuquq, the Uyghur Eletmish Bilgä Qaghan) and the testimonies of the Arabic and Persian written sources. Scholars also used, extensively, the place-names and tribal names of the indigenous population of Tuva, Khakassia, and the Altai. Kyzlasov was one of the first scholars to analyze in great detail the written records and other evidence on the Az tribe, associated with the population living in the territory of Tuva in the 6th to 8th centuries (1969: 50–52). He came to the conclusion that the Cik and the Az, who were the ancestors of the modern Tuvan population, lived in this area. Both tribes maintained a close relationship with the Qirqiz. The Cik settled in Western and Central Tuva. The mountain (or mountain-taiga) Az lived at the junction of the Western Sayan and the Altai Mountains, in the highland steppes of Southeastern Altai and the westernmost part of Tuva (the area of Lake Kara-Khol) (Ibid.: 50), and the steppe Az lived to the north of the Sayan Mountains, in the territory of the modern-day Khakassia, in the immediate vicinity of the Qïrqïz. The text dedicated to Köl Tegin mentioned twice his “brown Az horse” (Malov, 1951: 42), which, according to Kyzlasov, might have indicated that the Az bred good horses (1969: 50). Both the Cik and the Az were Turkic-speaking (although they might previously have spoken the language of a different group, and been Turkicized only at a later period) (Ibid.). I fully agree with the conclusions of Kyzlasov.

According to Kyzlasov, the (mountain taiga) Az settled in the entire Altai; they were under protection of the Turgeshes, and even were one of the Turgesh tribes (Ibid.). The previously-mentioned appointed ruler of the Turgesh Qaghan (the “tutuk of the Az people”) resided in the Altai. According to the Muslim authors, the Turgeshes were divided into the Tokhsi and the Azi. According to V.V. Bartold, “the reading of these names is doubtful; it is possible that the Azi are identical to the Az, mentioned in the Orkhon inscriptions” (1963: 36). B.B. Mongush also believed that until 711–715, the territory of the Altai and Western Tuva might have been a part of the eastern wing of the Turgesh State, the union of the Kara Turgesh (2013: 148).

N.A. Serdobov believed that the modern-day Teles were a special tribe formed in the Altai-Sayan as a result of the mixing of the local tribes—primarily the Az—with some tribes of the Tiele and part of the Tugyu Turks (1971: 44). Using the same written sources,

Serdobov, Kormushin, and Mongush supported the view of Kyzlasov on the division of the Az into the steppe and the mountain-taiga groups, and on the above-mentioned territories of their residence (Ibid.: 49; Kormushin, 1997: 12; Mongush, 2013: 146–147). Serdobov suggested that the Az and the Cik were not only the related tribes, but also formed a tribal union headed by the Cik, had common allies (the Qïrqïz, the Qarluqs, and the Tokuz Tatars), and a common enemy—the Tugyu Turks (1971: 52). According to Mongush, the Az were incorporated into the military-administrative system of the Uyghur Khaganate, enjoyed the confidence of the Uyghurs, and took their side during the uprising of the Cik in 750-751 (2013: 147).

Probably the most original point of view on the ethnic name az was held by V.Y. Butanaev (Butanaev, Hudiakov, 2000: 71–73). He considered the Az an elite part of the Qïrqïz, and identified them as the “royal family of the Qïrqïz State, recorded in the Chinese chronicles in the form of ‘azho’ (‘azhe’)” (Ibid.: 72). This view was supported and developed by T.A. Akerov (2010). However, in the light of all the above-mentioned evidence from the written sources and the arguments of the scholars, this hypothesis seems to be insufficiently justified.

According to Mongush, the etymology of the ethnic name qïrqïz sheds some light on the origins of the Az and the Qïrqïz people. The name can be read in a traditional way as “qïrqïz”, but also as “qïrq-az” or “qïrïq-az” (“forty Az”—forty tribes or clans of the Az) (2013: 148). Mongush suggested that forty clans of the Az separated from the old Az tribal union in the territory of Khakassia and, having mixed with the local tribes, formed a new “Qïrq-Az” nation—the Qïrqïz people—while other Turkicized parts of this tribal union became a part of the Turgeshes (the Altai-Tuva Az) (Ibid.: 149). This hypothesis, based solely on a questionable assumption from the reading of the name of the Qïrqïz, also seems doubtful.

Mongush suggested that the Az were the Turkicized descendants of the Iranian-speaking Asiani-Wusun, and a part of the Semirechye Asiani was involved in the migrant flow together with the ancestors of the Turks from the Eastern Turkestan to the Altai and further into the territory of Tuva and Khakassia, where they became known as the Az (Ibid.). A similar view was expressed by Akerov (2010).

There is no doubt that numerous groups of Old Turks, who left horse-burials, lived together with the Az in the territory of the Altai and Tuva. The great similarity among the Turkic horse-burials (burial rituals and grave goods) in the Altai, Tian Shan, and Western Tuva is an undeniable fact. It is difficult to correlate with certainty any Altai archaeological sites of this period with the Az. Even Kyzlasov wrote that the burial mounds of the

Az in Southeastern Altai and Western Tuva could not yet be identified, while he did note the sites of the Cik (burials without horses) and their relationship with the Shurmak culture (1969: 52). According to Serdobov, one of the recorded accumulations of stone statues in the area of Lake Kara-Khol may be attributed to the Az (1971: 50).

A.A. Gavrilova believed that the Kudyrge type of burials in the Altai region, with typical and distinctive artifacts, did not belong to the culture of the Old Turks; and other ethnic groups could have left them (1965: 104–105). Thus, can it be the case that these burials were left by the representatives of the Az tribe? At least, the preliminary data of radiocarbon analysis show that the Kudyrge and the Katanda antiquities are not the chronological and stadial phases of a single archaeological culture. The “Kudyrge people” and the “Katanda people” coexisted at least throughout the 6th to 8th centuries. The Turks (“Katanda people”) lived mainly in the Central and Southern Altai. Burials of the Kudyrge type are more specifically confined to the territory of the Eastern and Northern Altai and its foothills. It should be noted (keeping in mind a possible entry by the Az into a tribal alliance with Turgeshes or the resettlement of some of them in the Tian Shan, as well as their kinship with the steppe Az) that the belt and bridle sets showing heraldic style also appear at the archaeological sites of the Semirechye, the Ob region, and Khakassia. Single burials containing such objects are known from Western Tuva (Ozen-Ala-Belig) (Weinstein, 1966: Pl. IX) and the Minusinsk Basin (rock burial at the Chibizhek River) (Kyzlasov I.L., 1999). The former monument is a single human burial without a horse, similar to the burials at the Gorny-10 and Osinki cemeteries at the Altai foothills. The collection of pseudo-buckles and other items of a belt-set, similar to the Kudyrge belt-sets, is a part of the collections in the Minusinsk Museum. They belong to the category of accidental finds, and apparently originate from the destroyed or looted burials in the Minusinsk Basin.

However, the parallels manifested by the Tashtyk materials in Khakass-Minusinsk Basin and the Kudyrge monuments in the Altai and its foothills (pseudo-buckles, buckles of the “Western” types, earrings, etc.) are much more important for our topic. These are not sporadic parallels, but the evidence for the historical connections between these groups of sites, as already pointed out by numerous scholars.

The distribution of objects in the heraldic style, and of some other typical objects in burial complexes in the south of Kazakhstan (Borizhar cemetery, Kok-Mardan, etc.) and in Tian Shan, confirms my hypothesis and the abovementioned suggestions of my predecessors (Bartold, Kyzlasov, and Mongush) that the Azi (the Az) were a part of the Turgeshes. Some scholars have already argued for a possible connection between the monuments of the pre-Turkic period from the Central Asia, and the Tashtyk culture of the Minusinsk Basin. It is possible that these facts confirm the hypothesis of the origin of the Az from the Iranian-speaking Asiani-Wusun*.

Interestingly, exactly the northern and eastern Altaians have a component as in their ethnic names. Thus, the Kyzlasov’s conclusions that the Az and the Turgeshes were some of the ancestors of the modern-day southeastern Altaians, seem to be convincing. In support of this hypothesis, Kyzlasov listed the names of clans: tört as from the Teleuts, tirgesh from the Tubalars, and baylagas ( baylak as – “rich As”) from the Altaians-Kizhi. The Khakas called the southeastern Altaians chystanastar (“the taiga Ases”) (Kyzlasov L.R., 1969: 50). According to L.P. Potapov, the names of the Telengit seoks ( Tёrt-as – “four Ases”, Djeti-as – “seven Ases”, Baylagas or baylangas – “numerous Ases”) suggest that in the Early Middle Ages, the Az tribe was a part of the Tiele tribes, and is certainly connected with the modern-day Altai population (1969: 166–167). Moreover, he believed that “the territorial proximity of the Cik to Eastern Altai in the 8th century is also undeniable, just as the proximity of the Az. At that time, the Cik and the Az could well have reached the Altai” (Ibid.: 168). According to Potapov, in early times, the Cik, just like the Az, had been a part of the Tiele confederation of tribes, and later their nomadic camps were located to the north of the Altai Mountains, in the steppes of the Ob region.

The presence of Az-Kyshtym Volost in the Kuznetsky Uyezd in the 17th–19th centuries is no accident. In the 16th century, the Az-Kyshtym lived between the Tom and the Ob rivers, mixed with the Teleuts (Ibid.: 169–170). Whereas, the word “az-kyshtymy” is translated as “the tributaries of the Az people”. It is impossible to disagree with the conclusion of Potapov, that “the Teleut Az-Kyshtyms represent the descendants of some small tribal groups that were in the Kishtym’s dependence from the Az who lived in the Sayan-Altai Mountains and then in the steppes of the Ob region…” (Ibid.: 170). The latter fact is very well correlated with the spread, in the 6th–8th centuries, of the Kudyrge monuments in the Ob region, which contained various objects (belt and bridle sets in the heraldic style, bladed weapons, protective lamellar armor, etc.) of southern origin. These monuments belong to several archaeological cultures (the Upper Ob culture, the Relka culture, etc.), which most likely have two-partite composition, including the local and migrant components.

In general, it must be emphasized that the idea of the identification of the Kudyrge antiquities with the Az people, who are known from the written sources, is only a hypothesis. It has a number of supporting arguments; but with the accumulation of new data, it will be either definitively confirmed or refuted.

Conclusions

We should agree with the suggestion of Erdal that the runic inscription from Kalbak-Tash II may have been a boundary inscription left by the people from the clan or tribe of Az, who, as is known, were several times defeated by the Old Turks in the early 8th century, but having lost their independence continued to live in the same territories. Notably, they seem to have used the Turkic language for writing (even if not for speaking). Many scholars, as P. Golden pointed out (1992: 142, 143), considered the Az not to be a Turkic-speaking tribe. This runic inscription may prove that either this tribe was Turkic-speaking, or it was in the process of adapting the Turkic culture.

The suggestion that the inscription from Kalbak-Tash II might have been a boundary inscription can find a confirmation in the presence of the Bichiktu-Kaya rock only 4–5 km from it, downstream of the Katun River

(Fig. 5). This narrow and cliff-like rock on the right bank of the river was a natural barrier that prevented groups of nomads or enemy forces from penetrating the Central and Northern Altai (and further, Western Siberia) from the territory of Mongolia, Eastern Altai, and Tuva. Remains of fortified structures (walls or embankment of stones) defending some open areas were found at that site (Soenov, Trifanova, 2010: 44, phot. 10, 11). The left bank was securely closed by a rock at the confluence of the Katun and the Chuya rivers.

The Bichiktu-Kaya rock is associated with a legend about the Mongolian Khan Sonak, recorded and published by V.I. Vereshchagin at the beginning of the 20th century (Ibid.: 72). The legend tells how during one of the invasions by the Mongols under Sonak’s command in the Altai, the Altaians blocked the narrowest mountain passes with piles of stones, including the pass through the Bichiktu-Kaya. Trying to bypass this stronghold, most of the Mongol army was killed. Khan Sonak wrote the curse of the Altaians, and forbade his descendants to invade the Altai any longer. Since then, the rock is called Bichiktu-Kaya (“rock with the inscription”). Apparently, such tactics (of using the advantage of narrow mountain passes) were also followed by the local population in previous historical periods.

Fig. 5 . View of the confluence of the Chuya and the Katun, and of the Bichiktu-Kaya rock.

The mouth of the Chuya and the place of its confluence with the Katun also served as the boundary between the tribes of the Altaians in the ethnographic period: the Telengits living in the valleys of the Chuya and the Argut, and the Altai-Kizhi in Central and Northern Altai. Is it possible that while addressing his fellow tribesmen, the author of the Kalbak-Tash inscription metaphorically referred to this natural frontier, additionally fortified by the people, and to further advancement to the Central Altai?

Some scholars have suggested a connection between the content of the runic inscriptions, and petroglyphs. We can support this point of view, since the mention of the hunters from the Az tribe in our runic inscription is vividly illustrated by numerous engraved hunting scenes and representations of hunters at this petroglyphic site.

The fact that the inscription from Kalbak-Tash II contains an ethnic name (the tribe of the Az) emphasizes the importance of this discovery. Despite their brevity, such examples of Old Turkic writing serve as substantial addition to the well-known Orkhon runic texts that tell us about the history of the Turkic Khaganates. They make it possible to estimate more reasonably the settlement of the tribes in the territory of the Altai-Sayan in the Old Turkic period; to reconstruct, to some extent, the events in the political history of the region, and to correlate them with the investigated archaeological sites.

Acknowledgements

I express my deepest gratitude to Professor Marcel Erdal of the Free University of Berlin (Germany) for his translation and interpretation of the Kalbak-Tash inscription, his comments on the inscription, and for permission to publish them, as well as for his valuable advice and criticism during our discussion of the inscription.