The Old Believers’ Churchyard: Semiotics of Cultural Space (The Case of the Ust-Tsilma Old Believers-Bespopovtsy in the Komi Republic)

Автор: Dronova T.I.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study addresses the structure of cemeteries and types of tombstones in the funerary tradition of the Russian Priestless Old Believers (known as Bespopovtsy) living in the Ust-Tsilma District of the Komi Republic. For the first time, a description of their graveyards, known as “mogilniki”, or “mogily”, is provided, and their history and preservation are outlined. Traditional beliefs concerning cemeteries and their arrangement are cited. The symbolism of the forms of tomb structures, reproducing not only canonical prescriptions and requirements, but also certain pre-Christian beliefs, is analyzed in detail. Folk terms relating to the dead and the afterlife are included. The degree and nature of post-revolutionary transformations, profoundly affecting the foundations of the Old Believers’culture, are explored. Despite the attempts to preserve traditions, modern lifestyles took root in the 1960s and 1970s. Elements of local specificity in funerary rites have nonetheless survived and can be seen in the symbolism of tombstones, synthesizing Christian and pre-Christian traditions. Findings of ethnographic, linguistic, and archival studies are presented.

Traditional culture, Russian Priestless Old Believers, cemetery, tombstones, deceased, ancestors

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146963

IDR: 145146963 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.4.126-134

Текст научной статьи The Old Believers’ Churchyard: Semiotics of Cultural Space (The Case of the Ust-Tsilma Old Believers-Bespopovtsy in the Komi Republic)

In the system of spiritual and religious values, the cemetery (from Greek κοιμητήριον, ‘sleeping place’) is one of the most important cultural objects, which is considered to be both the final resting place of a person and most importantly, a sacred place for keeping ritual dialogue between the living and the dead. In his Homily on the Cemetery and the Cross, John Chrysostom speaks about this: “Since today Jesus descended among the dead, for this reason we are gathering here. For the same reason, moreover, this place is called a koimeterion, in order that you may learn that those who have reached their end and who lie here are not dead, but rather are sleeping and resting. <…> Hence, the place is called a koimeterion, for the name is both useful for us and full of much wisdom” (John Chrysostom, 2022: 7, 9). Believers associate graveyards with light and a bright life. Popular ideas about this emerged under the influence of Patristic writings about the heavenly afterlife, which the Holy Fathers discussed upon the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ. St. John Chrysostom thus says in his Homily Let No One Mourn the Dead: “…after escaping the dark life and leaving for the true light, we bury [the dead] towards the east, signifying the rising of the dead”. In the mythological worldview, the cemetery personified “the other world” and was considered a “foreign realm”, which required a respectful attitude and corresponding

behavior. According to the observation of S.M. Tolstaya, “the cemetery turns out to be a whole world inhabited by special ‘residents’, who have their own rules, restrictions, and boundaries, which require the mastering of proper rituals, which makes a cemetery something like ‘an embassy of the other world’ on earth” (cited after (Andryunina, 2013: 43)).

A distinctive aspect of cemeteries and burials among the Old Believers is that they bury their fellow believers in a separate location from representatives of other denominations, often separating their burials with an enclosure. Cemeteries in rural settlements are of particular interest. Arranging them, the Old Believers were guided by both ecclesiastical concepts about the afterlife and preChristian beliefs. This article will examine the history of the creation and functioning of cemeteries among the Priestless Old Believers living in the Ust-Tsilma District of the Komi Republic. Until now, this topic has not been studied nor did it attract the attention of travelers and writers about everyday life who visited the Pechora region in the 19th century. This study is based on modern field materials of the author (hereafter, FMA), as well as records kept in the Scientific Archive of the Komi Science Center of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (hereafter, SA KSC UB RAS). Some information on this topic was also found at the State Archive of the Arkhangelsk Region (hereafter, SAAR).

Location and structure of the cemetery

The development and operation of rural cemeteries in the Ust-Tsilma villages were associated with denominational issues and with the emergence of villages especially during the period of intensified repressive policies under Tsar Nicholas I (1825–1855), aimed at eradicating the Old Believers’ faith. Families tied by kinship or several family clans settled within the boundaries of a single village. Therefore, a specific feature of cemetery development in the villages along the Pechora River was their quantity. In some villages, there were several graveyards named after the founders of family clans. Even in the 1950s, there were five cemeteries (previously, there had been even more) in the volost (later, district) village of Ust-Tsilma. Some of these cemeteries bore the names of family clans: “Ivanovo” (originally emerged as a holy place), “The Fedoseikov Family Cemetery”, and “The Semyonov Family Cemetery”. In addition, there existed a public cemetery “At the Forest Grove”, where Christians of the official Orthodox Church were buried, as well as Old Believers some distance from them, and a graveyard where Ust-Tsilma residents who died from the Spanish flu were buried. There were four cemeteries in the village of Koroviy Ruchei (“The Ivankov Family Cemetery”, “Ipatovsko”, “The Startsev Family Cemetery”, and a common village cemetery), two each in the villages of Garevo and Chukchino. Two graveyards in the settlements of Zamezhnaya and Zagrivochnaya on the Pizhma River appeared under the following circumstances. The former settlement what is now the public cemetery is located near the village, while the burials of representatives of the Churkin-Kirikov family clan are beyond the Pizhma River. In the latter settlement, a graveyard on a high hill over the river ended up within village boundaries due to heavy development and was closed in the 1970s. Currently, there is one cemetery operating one km from the village.

A particular situation occurred in rural settlements inhabited by various ethnic groups, primarily in those bordering with the Komi and Nenets people. The Komi were buried separately in the village of Neritsa despite the fact that they were Old Believers. The situation was the same with the Nenets: “ In the past, in Neritsa, people were buried separately, near their houses. The Komi, Nenets, and Russians were buried in families, and under the Soviets already in the same cemetery. In the past, there were people exiled; this was after the Great Patriotic War; they were buried apart, and instead of a cross, fir trees were planted ” (FMA. Recorded in the village of Ust-Tsilma in 2022 from an interview with L.O. Babikova, born in 1966). In other villages (even those near the border), people were buried according to the family clan principle: graves of the representatives of a particular family clan were grouped in one place.

The graveyard is a village of the dead, according to a children’s riddle: “The village is inhabited, / Roosters do not crow, / People do not get up. – A cemetery ” (Deti…, 2008: 87). The Ust-Tsilma Old Believers believed that a graveyard was a holy place: “ The cemetery is the most holy place, there is no holier place. There is eternal peace, no swearing, no cursing, no fighting there. The deceased rest there. People only pray there and commemorate the deceased with good words ” (FMA. Recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2009 from an interview with A.M. Babikova, born in 1922). Naming the area that separated the cemetery and residential buildings in the village of Zamezhnaya “ Christ’s Swidden ”, was associated with the idea of the holiness of the graveyard. This land remained deserted for a long time, and only in the 20th century (after the Revolution of 1917), did the village administration organize its development.

In the Ust-Tsilma terminology, a cemetery is called a mogilnik or mogily (‘graveyard’ or ‘graves’). The Ust-Tsilma people did not formerly use the term kladbishche (‘cemetery’); only starting in the 1960s, did it gradually begin to be employed: first, by young people returning to their home village after studying in the cities, then, by middle-aged rural residents and Soviet-minded young people who disdained everything traditional. Currently, the designation mogily (‘graves’) is used exclusively by pious elderly people who observe old Church canons and the rules of the fathers.

Archaic beliefs about the structure of cemeteries and graves have been largely preserved among the residents of villages along the Pechora River who may have inherited these traditions from the first settlers. A high, dry, and light-filled place beyond the fields, near a stream, beyond a river, or next to it, 200–300 m from the residential area, was chosen for a graveyard. Most of the Ust-Tsilma cemeteries are located on hills, since the Old Believers associated “the other world” with a mountain, the “upper world”: “ our parents are watching over us from above ”; “So we are carrying you to the big mountain, / To the big mountain, yes, to the sloping one” (funeral lament). The expressions “ our parents are watching us ”, “ they are watching our life ”, “ our parents wait for prayers from us ” reflect beliefs about the uninterrupted connection between the living and the dead: “ My parents, grandpa, and grandma, are buried in our cemetery, beyond the fi eld. When I lug manure in the morning, I greet them. They watch us; we watch them. This is how life works ” (FMA. Recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2009 from an interview with I.A. Babikov, born in 1940).

In a number of villages along the Pizhma River, cemeteries are located on the opposite bank of the river; in Ust-Tsilma and some adjacent settlements, beyond the stream. The role of the river as a mystical road connecting the worlds is well known and is reflected in folklore and funeral rituals (Levkievskaya, 2004: 345–347). Crossing the river by the deceased is associated with relocation to the “other world”, which is the end point in the journey of the soul of the deceased person, and with cleansing the soul from earthly sins: “ People are buried beyond the river. We must bring the dead across the water. It is said, their sins are cleansed, and the pure soul will go to heaven; the sins remain on the home side ” (FMA. Recorded in the village of Borovskaya in 2010 from an interview with O.E. Chuprova, born in 1954). It is no coincidence that in the past, the clothes taken from the deceased, the items used for washing the body, and the wood chips left from making the coffin and cross, were brought by the Ust-Tsilma Old Believers to the river, which was supposed to carry everything away from the deceased. In funeral laments, the deceased “sails away” to the “other world” in a “ light-weight boat, a boat made of spruce, without an oar for rowing ”. Currently, rural residents have lost their understanding of the river as the most important component of the model of the Universe. Since transporting the deceased across a river/stream is now considered a laborious and meaningless process, in the 21st century, new graveyards began to emerge near villages.

Two cemeteries in the Ust-Tsilma District—in the villages of Skitskaya (Dronova, 2007a) and Ust-Tsilma

(Ivanovo cemetery) (Dronova, 2007b)—are located in areas associated with religious practices. The former is related to Velikopozhensky Skete (from the first third of the 18th century to 1857). Two large eight-pointed crosses and a chapel where the remains of skete dwellers who ended their lives by self-immolation in 1843 were laid to rest, were built at that cemetery. In the 1970s, a votive prayer barn funded by P.P. Chuprova was built there. Both the barn and the cemetery operate to this day.

A revered place in the village of Ust-Tsilma is associated with the locally revered saint Ivan, whose name led to various designations, such as “Ivanov Hill”, “to Ivanushka”/“at Ivanushka”, used in the late 19th century (SAAR. F. 487, Inv. 1, D. 15, fol. 5); “to Ivan”, “Graves at Ivan’s”, “Ivan’s Hill”, and “Ivan’s Cemetery”, which are still actively used today. Currently, the notion of going “to Ivan” is also used by the Old Believers to mean “it is time for eternal rest”. Over the saint’s grave, a chapel was built, which was renovated twice over the past century. Traditionally, a commemorative service to Ivan is served there on St. John the Baptist’s Day (July 7, according to the Gregorian calendar). The “feedback” of the dead to the living is believed to be strengthened if the deceased was a righteous person or a saint. People make votive prayers there, ask for help and, as Christians believe, receive it, which confirms the importance of the sacred place in ritual practices of the Ust-Tsilma residents. Until the mid-20th century, mentors and devout Christians were buried at the Ivanovo cemetery. During the Soviet period, the revered place was defiled. The village administration insisted that all the dead, including “unclean persons”, had to be buried there. Many elderly villagers were outraged by the fact that contrary to the opinion of deeply religious people, in the 1950s, members of the Communist Party who destroyed the traditional way of life were also buried there in the center of the revered place: “ The precepts of our parents were completely disregarded. Party members are buried next to devout people. In the past, they did not do that; those were buried behind, on the side. And now, what can I say, everything is all mixed up ” (SA KSC UB RAS. F. 5, Inv. 2, D. 568, fol. 32). A similar practice is also typical for other Old Believers’ areas (Kovrigina, 2014: 240). Currently, all cemeteries in the Ust-Tsilma District are Old Believer cemeteries; those who adhere to the official Orthodox church are also buried there.

Archival documents testify to the complex attitude of the government and Church officials towards family cemeteries in the 19th century. With the intensified persecution of Old Believers in the 1830s–1860s, it was quite difficult to maintain the tradition of burying people at family cemeteries, since it was prescribed to bury Old Believers only at common parish graveyards. It is known from the archival document “Secret Instructions on the Procedure for Burying Dead Schismatics” that until 1839

they were allowed to be buried “only near Orthodox cemeteries”, and those who disobeyed were strictly forbidden to be issued death certificates (SAAR. F. 1, Inv. 4, V. 5a, D. 584, fol. 9v). Therefore, the Ust-Tsilma residents “buried the bodies of dead schismatics not at cemeteries, but near their homes, which is prosecuted, and perpetrators are brought to justice” (SAAR. F. 538, Inv. 1, D. 51, fol. 5). Seeing the hopelessness of measures aimed at closing Old Believers’ graveyards, the local authorities referred to the circular order of the Ministry of Internal Affairs from December 14, 1839, No. 7670 and ordered: “Regarding cemeteries for schismatics: the Sovereign Emperor, taking into consideration, on the one hand, that according to the popular understanding, most of those who are about to die, wish to be buried in the same place as their ancestors, thus gives his supreme order: 1. Leave the currently existing cemeteries of the schismatics who do not accept the priesthood from the diocesan authorities and perform burials according to their own rites, but in the future, do not allocate special cemeteries but give them a separate place at common cemeteries. With the absence of priestly funeral rite, bodies must be buried only after certification by the local police; 2. It is not forbidden to bury former schismatics at common cemeteries” (SAAR. F. 1, Inv. 4, V. 5a, D. 584, fols. 11r–11v). Relatives who secretly put their loved ones to rest without a Church funeral service were strictly punished: “In 1855, for burying their daughter in an ‘unspecified place’ and without a Church funeral service, Savva and Matryona Ostashov from Ust-Tsilma were punished with 30 lashes by a birch rod. The court sentenced four other Ust-Tsilma residents for burying their relatives, although in a ‘legal’ place, but without a funeral service by a priest, to village detention for three weeks” (Gagarin, 1975: 121). However, despite the severity of punishments, the Ust-Tsilma residents still followed the traditions “of their grandfathers” and buried the deceased at their cemeteries, but earlier than the usual day, sometimes on the day of death, in order to avoid a Church funeral service.

The years of 1900–1903 were marked by a new wave of directives to close down family cemeteries. It was ordered to close them down in seven villages “adjacent to the Ust-Tsilma parish”, and one on the Pizhma River in the village of Zagrivochnaya, 10 versts from the parish in the village of Zamezhnaya “as being illegal” (SAAR. F. 29, Inv. 2, V. 6, D. 287, fol. 6). The cemeteries that were in the villages listed in the archival file are still operating now.

The Komi Old Believers’ settlements faced a different situation: the matter of burying Old Believers was considered by the local authorities to be under state regulations of the early 19th century: “…schismatics must not be buried together with the Orthodox, because, at the suggestion of the Committee of Ministers of May 7, 1812, special places are allocated for their burials, away from the villages, which should be supervised by the parish priest, the rural dean, and the county police” (Vlasova, 2010: 132).

In the arrangement of cemeteries, focus was placed on the natural environment: it was strictly forbidden to cut down the forest; the graveyard always stood out against the background of a village or empty landscape. The place chosen for the cemetery was consecrated: the land was censed while reciting the Jesus Prayer. Trees were not planted on purpose, but subsequently people carefully looked after the territory. Dried trunks were cut down and taken outside the graveyard, where they decayed fully. The removal of trees, branches, berries, mushrooms, and grass from the cemetery was strictly forbidden. It was believed that those who violated the ban doomed themselves or their loved ones to misfortune. However, it was allowed to take away things used on the day of burial, such as the censer from which the coals were always poured onto the grave, and working tools. In the past, while transporting the deceased to the cemetery, the coffin was covered in accordance with the sex of the deceased. Woman’s coffins were covered with a large scarf, men’s, with a veil. After the burial, the covers were given to the godchildren for commemoration of the soul, and if there were none, to the closest relatives. Long towels on which the coffin was lowered into the grave were immediately torn into pieces and distributed to the gravediggers or orphans.

In the past, Ust-Tsilma cemeteries and graves were not surrounded by enclosures, which emphasized the special quality of the world of the dead: “the other world” had no boundaries, the deceased were “returned” to nature. Ideas about the need to make a fence around the graveyard vary in different areas. Ambiguity of attitudes towards this is also present in the Old Believers’ regions (Kozhurin, 2014: 514). It was also not customary for the Tuvan Chapel Old Believers and Ural Old Believers to make enclosures around cemeteries and graves. This was explained by the obstacles “that a person would have to face on the Judgment Day: it would be difficult for him to get out of the grave because of the iron fence” (Danilko, 2019: 53). However, it is also known that among Old Believers on the Vyg River, already in the 19th century, cemeteries were “enclosed with a log fence” (Yukhimenko, 2002: 333). Enclosures were also made in non-Old Believer areas (Dobrovolskaya, 2013: 113).

Despite the stability of the funeral rite, innovations in the arrangement of graveyards and graves appeared during the Soviet period due to radical changes of life in the countryside. Before collectivization, pasture and hayfields in the villages along the Pechora, Pizhma, and Tsilma rivers were located beyond the river, where the villagers brought all of their livestock and resettled themselves in the spring. During collectivization, economic life in the villages changed: individual farms ceased to exist, and peasants were forced to work on collective farms, leaving their livestock in the village. Cattle wandered around the surrounding areas, including cemeteries, which made it necessary to fence them with funding from village councils. Other innovations also appeared in the 1960s–1970s, such as painted grave structures, wreaths, and artificial flowers on graves. According to the Old Believers of the older generation, these changes were associated with loss of faith and traditional beliefs about the deceased, with a disdainful attitude towards ecclesiastical laws and the delusion that the deceased need “decoration”: “The dead body does not need decoration. The dead wait for prayers from us. My mother said that those who are not commemorated simply lie like stones. While those who are commemorated – those souls fly to heaven” (FMA. Recorded in the village of Chukchino in 2008 from an interview with E.A. Babikova, born in 1950).

Nowadays, all cemeteries have fences. Some burials are surrounded by a wooden or metal enclosure around the space “reserved” for relatives. All grave structures are painted; the inscription concerning the deceased on the cross/post is replaced with photoceramics; red stars are nailed to the monuments of war veterans. This enculturation is associated with modern ideas about the memory of the deceased. Importantly, some innovations are now welcomed by the believers: “ People will come to the grave, see the photograph, and will commemorate, remember ”. Similar innovations are also typical of the Old Believers living in other Russian regions (Kovrigina, 2014: 239).

In the villages along the Pizhma and Tsilma rivers, at every cemetery, one can see stretchers or poles leaning against a tree. On the day of the funeral, gravediggers bring them, and after transporting the coffin, they leave them at the graveyard. In the village of Ust-Tsilma and villages along the Pechora River, people use household poles, which are then returned to the household owners: “ the poles are disassembled so that the soul of the deceased would not return to the house ”.

As in all places, graves at the cemetery are located along the EW line: the deceased is “ buried with his feet towards the east, facing the Last Judgment ”; according to John Chrysostom, “We bury [the deceased] towards the east, signifying the raising of the dead”. The cross or post installed at the feet is associated not only with identification of the deceased, but also with the idea that he/she is praying while looking at the cross or icon, inserted into the post.

Types and varieties of funerary monuments

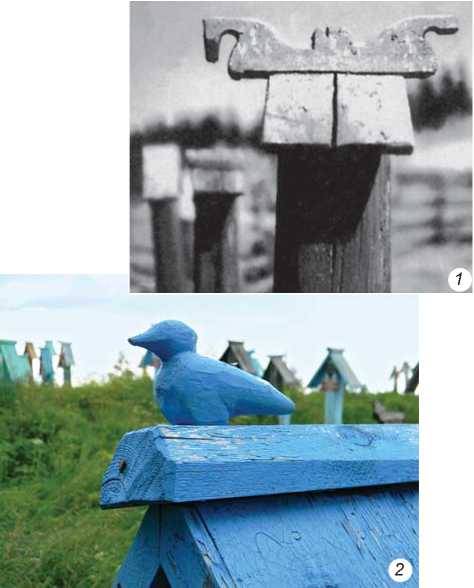

Three types of grave monuments were traditionally made in the Ust-Tsilma villages: crosses, high posts for adult burials, and low posts for children. Their height matched the height of the deceased person. All had a gable roof. Eight-pointed crosses were placed on the graves of mentors and ordinary Old Believers who died of natural causes. The Cross is the main Christian symbol signifying the victory of Christ over hell and death. The Cross is “the will of the Father, the glory of the Only Begotten, the exultation of the Spirit, the adornment of the angels, the security of the Church, the boast of Paul, the rampart of the saints, the light of the whole world” (John Chrysostom, 2022: 14). In the Russian North, setting up wooden crosses was primarily associated with piety. In villages, they were placed near houses; on the Kandalaksha, Tersky, and Zimny coasts of the White Sea they were put at fishing grounds, at encampments, as a “sign” along the roads, in memory of dead sailors and hunters; and they were set up as a vow, or in graveyards (Ovsyannikov, Chukova, 1990: 63). The installation of a grave cross was associated with the ideas of a bright afterlife, with hope for the future resurrection and eternal life for the souls of the deceased. It was based on a pillar hewn from a log with a diameter of 25–30 cm; two crossbeams were attached at the top. The upper crossbeam had arms 15–20 cm long, and the lower one had arms up to 50 cm long, on which a recess was made in the center and a cast icon was inserted (Fig. 1). Wooden icons, as was customary on the Vyg, were not attached to grave monuments in Ust-Tsilma villages. Another, slanted crossbeam was placed at the bottom of the pillar. The pillar’s top was sharpened and a roof was attached. The bottom of its slopes was shaped in the form of five pointed teeth associated with five fingers. The inscription was pecked on the pillar: “Here lies the body of the servant of God (full name), born (date), died (date)” or “The body of the servant of God (full name), born (date), died (date) rests here”. In the past, the roof ridge of the cross was decorated with carved stylized figures of animals or birds (Fig. 2). Horse head images facing in opposite directions were carved at the ends of the ridge. This decorative motif goes back to the 1st – early 2nd millennium AD, when women’s clothing was decorated with horse-shaped pendants (Gribova, 1975: 77). The cult of the horse is reflected in the art of the Russian North, as evidenced by images of horse heads on the roofs of Mezen houses or figures of horses on Palashcheliye distaffs (Dmitrieva, 1988: 158). In the ancient Slavic tradition, the horse was a sacrificial animal in the funeral rite, and was considered a guide to the “other world”. The design of grave monuments might have been related to similar ideas. Such roof ridges of grave monuments are widespread in the Komi culture and in the Ust-Tsilma villages neighboring the Komi-Izhma villages. A similar design of the roof ridge in burial structures has also been observed in the Udora villages of the Komi Old Believers (Vlasova, 2010: 139).

Eight-pointed crosses on the graves of mentors and those who were well-versed in Old Church Slavonic stand out at the cemeteries examined by the current author. According to the stories of old-timers, when those reached old age, they each made a cross for themselves and kept it for several years in the povet *.

Since the 1960s, eight-pointed crosses began to be simplified and replaced with six-armed and sometimes four-armed crosses, which, however, did not become very widespread. Currently, grave crosses are not produced in all settlements of the Ust-Tsilma District. This is explained by the fact that people have departed from the faith and do not comply with church laws. The Kerchomya Komi Old Believers explain replacement of eight-pointed crosses with posts: “My grandfather saw the point of setting up a post in the fact that if you put up a cross, you need to fence off the place so dogs and other creatures won’t defile the cross. But it is difficult to keep track of this, so it is better to set up a post instead of a cross” (Shurgin, 2009: 82).

Since the 1960–1970s, high or low posts, previously intended for “secular” Old Believers (those who married the representatives of a different religion), have become widespread as grave monuments. Posts were also placed on graves in the Russian Old Believers’ settlements of the White Sea region (Opolovnikov, 1989: 140). In the mid-20th century, the tradition of burying people who died an unnatural death outside the rural cemetery was interrupted. They began to be buried in the circle of family graves, and a grave monument (a post with a roof) was erected. The post was square in cross-section; the upper part was slightly wider than the base and was interpreted as the “head”. The roof was the same as that in burial structures of the first type. Nowadays, the post is often made the same width along its entire length, which is primarily associated with loss of beliefs about it as a projection of a person. There is also another explanation: “ They are in a hurry and do not want to shape it. It is faster that way ”. Changes also have affected the design of the bottom part of the roof slopes. It is either flat or the number of teeth varies from four to seven.

In the 1970s, “a cross or post was placed on the grave in accordance with ‘what the parents would tell’ their children before death. Yet, that being the case, only those who deserved it by strictly observing the canons of faith, were honored by the cross. After death, the majority of ordinary Old Believers were expected to set up a post on their graves and put a small copper icon on it—the Crucifix and images of male saints for the male deceased, images of the Mother of God and female saints for the female deceased” (Shurgin, 2009: 82). According

Fig. 1. Cemetery in the village of Ust-Tsilma. Photo by T.I. Dronova .

Fig. 2. Decoration of roof ridges of grave monuments in the villages of Garevo ( 1 ) and Trusovo ( 2 ) of the Ust-Tsilma District. Photo by I.N. Shurgin and T.I. Dronova.

to popular beliefs, the deceased “gets up” and prays while looking at these icons. Similar ideas existed in other areas of the Russian North (Ivanova, 2007: 121). In the last three decades, eight-pointed crosses cut out from aluminum (for male burials) or baptismal crosses (for female burials) have been attached to grave monuments instead of icons due to more frequent cases of vandalism since the 1980s. Outsiders sometimes remove icons from grave monuments and damage burial structures. As the carriers of the culture say, “the crosses/posts stand blind now”. Many elderly believers procure such crosses during their lifetime and notify their loved ones about their location.

Until the 1980s, the third type of grave structures was intended for baptized infants and adolescents. At present, it is also used for unbaptized infants. The post was made of thin beams (10–15 cm in diameter). The bottom of the gable roof was left even. The top was equipped with a horse-shaped ridge decoration. An icon was not installed. Instead, the last name, first name, patronymic name, and date of death were pecked out. In the Komi Old Believers’ villages, small crosses were set up on children’s graves (Vlasova, 2010: 140).

Rare grave structures include low posts under a wide roof with gables, a traditional stylized horse and two slopes, the bottoms of which are shaped like sharpangled teeth. Such monuments called namogilnichki (lit. ‘small monuments on the grave’) were common on the Vyg River.

Monuments of a low tetrahedral pillar with spherical top appear at cemeteries in three rural settlements along the Pechora River (villages of Ust-Tsilma, Karpushovka, and Koroviy Ruchey). Similar monuments have been observed on the Pinega and Mezen rivers. In the Ust-Tsilma villages, “posts without icons, with ‘knob’ tops, marked the burials of all those who died an unnatural death, without repentance, and therefore were not worthy of holy icons” (Shurgin, 2009: 83).

In the village of Skitskaya, which emerged on the site of the cells of the Velikopozhensky monastery, back in the first third of the 20th century, grave monuments were made similar to the Vyg low tetrahedral posts with hewn edges, decorated with carved geometric patterns. The remains of three such monuments were placed in a pit next to massive crosses and a small log building where, according to oral tradition, the bones of self-immolating Old Believers were buried. Currently, low, eight-pointed crosses and posts are put on graves.

In the past, burial structures were not painted but were left in their natural state. Now, as before, monuments are made of larch, with the lifespan of the larch items exceeding fifty years. When a cross or post decays, the remaining part is taken to the outskirts of the cemetery and the burial becomes nameless. It sometimes occurs that when digging a grave, people come across an old coffin and bury the newly deceased nearby or higher.

Grave arrangement followed the idea that it was the last home of a person. According to the Christian understanding, death is a milestone that ends a person’s temporary earthly life and opens the eternal life of the soul. According to the Ust-Tsilma proverbs, “A person is born for death, but dies for life”, “We are born for a visit, but we die for an age”, “We are born for an age, but we die for life”. As O.V. Nikiforova observed, “birth is not the beginning since death is inevitably intrinsic to birth; birth predetermines death. Death is also not the end, because life is embedded in death. Death predetermines life just as life predetermines death” (2015: 489). When escorting the deceased to the “other world”, people would arrange his/her burial place taking these ideas into consideration. At cemeteries, some grave monuments consist of two parts: a cross/post and a domovina (variants: golubets (Tsilma, Ust-Tsilma), golubnitsa (Ust-Tsilma) (Markova, Nesanelis, 1990: 100), or sklep (Zamezhnaya); in the Russian North, these were called srubtsy). Scholars attribute such burial structures to the pre-Mongol period (Ermonskaya, Netunakhina, Popova, 1978: 28). Currently, they have survived mainly among the Old Believers. Residents of the Ust-Tsilma District do not know the origin of these wooden grave structures. In the Dictionary of V.I. Dahl, golbets is “a grave monument of logwork with a roof, booth, or hut; now they are prohibited; all monuments are also called this, especially a cross with a roof” (1880: 380). In Rus, the word golubets had two meanings: a grave monument with a carved post and roof, and an extension near the stove covering the entrance to the basement. Both meanings are related to the concept of “depth”. In Ust-Tsilma villages, the use of the word golubets as a name for a grave monument has not been identified, but it is applicable to a plank structure covering the grave mound. According to popular beliefs, the coffin/golubets is the last home of the deceased. This idea can also be reconstructed from the folklore texts: “new upper room”, “bright room”, “bright room without doors and without windows”, “bright room without windows and jambs” (Pechorskiye prichitaniya…, 2013: 133), “a built nest”, “new high chamber”, “new upper room”, “evil wicked chamber” are the names of the coffin in funeral laments:

They gave you a new room. A new room, but without gaps, Without removed grooves.

The chamber is bright, yet without windows, Without brick stoves, Without squeaky doors.

There will be no way out from that room.

No going out and no leaving it

(SA KSC UB RAS. F. 5, Inv. 2, D. 568, fols. 5–6).

The opinions of the present-day Ust-Tsilma Old Believers regarding the use of domovina/golbets/ golubnitsa differ. Some believe that this is the last home of the deceased. Others explain the purpose of the structure as follows: “so that the grave not be trampled”, “now everyone without exception smokes—so that tobacco would not fall on the ground”. According to L.F. Soloviev, a resident of the village of Zamezhnaya, grave plank structures on the Pizhma were called sklepy; their construction was not large scale, these were rather individual cases. In fact, most Pizhma residents believe that the soil at the grave should be open. “In recent decades, it has become fashionable to cover graves with boards for beauty. Some people plant flowers on top. But this was not done before” (Ibid.: fol. 39).

All burial structures known to the current author have been made of boards. They have a gable top (roof). To prevent water from getting inside, the boards were overlapped by stacking. Roof slopes were connected by a board. The custom of cutting out a “window” that remained open in one of the walls of the domovina is associated with the idea of the domovina as the person’s last home. Later, people began to make a hole in the roof of the golubets , and cover it with a lid. Old Believers thus explained the purpose of the “window”: “so the deceased could see the Second Coming of Christ” (Gunn, 1979: 114). Only near the Tsilma River, in a locally revered place of worship on the Tobysh River called “At the Deceased”, does the domovina consist of logwork with two layers connected by one transverse log thereby leaving a gap between the layers. The top is flat and is made of tightly placed thin logs. A similar design of graves is now practiced among the Upper Pechora Old Believers- skrytniki (lit. ‘the hidden ones’) in the village of Skalyap.

During the Soviet period, the government introduced significant changes to the life of traditional society, which also affected the structure of cemeteries and funeral culture, since centuries-old traditions were recognized as being backward and relics of the past. The Ust-Tsilma Old Believers call the Soviet period the most destructive, when not only books and icons were burned, but cemeteries were destroyed. As the old-timers recall, “ they eradicated the sacred ”. Five cemeteries were closed in Ust-Tsilma (plowed over for fields, passed on for construction sites), and one cemetery was closed in each of two adjacent villages.

Attempts were made to eradicate traditional lamentations for the deceased on the day of the funeral/ commemoration. As in all places, the division of burial places by religion was abolished (Mokhov, 2014: 252). People who died an unnatural death were buried along with everyone else. In the 1970s, funerals with the participation of brass bands were introduced (this is how the members of the Communist Party and veterans of World War II were mostly buried), but in the postSoviet period this innovation disappeared. Currently, stone monuments have been set up in Ust-Tsilma, which, according to old-timers, is unacceptable. The understanding that items accompanying the deceased to the “other world” must be subject to natural decay remains in the burial culture of the Ust-Tsilma Old Believers. In the past, burial structures were not restored. It was believed that with their natural decomposition, the deceased would join the ancestors, which were called in funeral prayers “not each by name, but all together”. Other monuments violated this order of things. In addition, in commemorative rituals of the Ust-Tsilma residents, stone was associated with oblivion. According to popular beliefs, a deceased person who did not receive commemoration, “lies like a stone”, “there was a memory, but it has become a stone”.

Despite the ongoing transformations, the desire to be buried next to one’s relatives according to the customary rules remains quite stable. Many Old Believers, who left their villages to reside permanently in the cities and towns of the Komi Republic, leave wills requesting that their place of repose be near their ancestors, and their relatives fulfill their last wishes.

Conclusions

This study has shown that cemeteries served as important places in the culture of the Ust-Tsilma Priestless Old Believers, being the location, according to people’s beliefs, where communication occurs between the earthly and other world. Until the mid-20th century, graveyards in the Lower Pechora region did not undergo major transformations due to the well-known self-isolation of the residents. The lifestyle of the Ust-Tsilma people is still determined by old ecclesiastical traditions, but since it does not encompass all aspects of life, traditional ideas and beliefs contribute to social order. This makes it possible to consider the Ust-Tsilma group as ethnic and confessional, and its traditional culture as local.

Family cemeteries, as well as traditions of arranging graveyards and graves, have survived from the time of the arrival of the first settlers to the Pechora River and its tributaries, the Pizhma, Tsilma, and Neritsa rivers. The cemetery is the world of the dead; every village has its own cemetery. In some settlements, there are several cemeteries, where burials are made according to family clan affiliation. Many graveyards are currently incorporated into the rural environment, but still operate. Attempts to close them have been unsuccessful.

In the understanding of the Ust-Tsilma Old Believers, death does not interrupt the relationship between people. The living take care of the burial places of their loved ones and pray for their repose, while the deceased “watch” the living and, depending on their actions, “send” grace or “punish” them for correction. This is revealed by the Ust-Tsilma proverbs: “ Burying the deceased is half the work; what is more important is how they will be commemorated ”, “ The dead does not stand at the gate, but brings out his own ”. Regulation of ritual actions performed at the cemetery is regarded as a way of ensuring grace and peace for the living and dead. Even today, the memory of the dead and belief in the afterlife makes young Ust-Tsilma residents turn to the ancient traditions of their grandfathers, thereby supporting and prolonging them.

Acknowledgment

This study was carried out under the state assignment of the Federal Research Center in the Komi Science Center of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Project State Registration Number FUUU-2021-0010).