The origin of the Karasuk people: craniometric evidence

Автор: Kozintsev A.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Anthropology and paleogenetics

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Measurements of 24 male cranial samples associated with the Karasuk culture were compared with those of 56 other samples using multivariate methods. On the dendrogram, the Karasuk cluster includes the Mongun-Taiga people, Saka, Sauromatians, Tauri, and a group from Sialk B. In the two-dimensional projection, this cluster is intermediate between the Andronovo and Okunev clusters, testifying to the admixed nature of the Karasuk population. In people associated with the Classic Karasuk tradition and in the north of the Karasuk area, the Okunev component predominates, whereas in members of the Kamenny Log tradition and in the south of the area, the proportion of the Okunev and Andronovo components is closer to equal. The use of twelve Andronovo samples conclusively disproves the belief that the sole ancestors of the Karasuk people were Andronovans. Mechanisms whereby Okunev aborigines were assimilated by Andronovo immigrants are discussed.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146990

IDR: 145146990 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.2.143-153

Текст научной статьи The origin of the Karasuk people: craniometric evidence

Karasuk is one of the post-Andronovo cultures. This does not imply, however, that it originated solely on the basis of Andronovo. Certain experts ascribe an important role in Karasuk origins to both Andronovo immigrants and Okunev natives (Vadetskaya, 1986: 61–63; Rykushina, 2007: 15, 20). Others believe that the key role was played by Andronovans whereas the contribution of the Okunev people was negligible (Poliakov, 2022: 211, 226, 245, 249, 290, 316; Gromov, 1995, 1996, 2002: 108, 110, 133). Both latter authors argue that the Karasuk population had descended from Andronovo migrants of the second wave from the west rather than from their predecessors—the Andronovo (Fedorovka) people of the Minusinsk Basin. A.V. Poliakov (2022: 290) associates the migrants with the Alakul tradition.

A direct bearing on our topic has the opinion voiced by Y.G. Rychkov (1969: 158–159): in terms of craniometry, Karasuk people were allegedly indistinguishable from recent Pamiris—Goranis, Ishkashimis, Wakhanis, and Rushanis. Were that true, the contribution of Okunevans to Karasuk origins would be quite unlikely, contrary to what the analysis shows. Another problem would concern the participation of Andronovans, whose light pigmentation has been demonstrated both directly, by genomic data (Keyser et al., 2009), and indirectly, by data relating to modern groups of Southern Siberia, which retain a high share of Andronovo genetic legacy and are markedly depigmented, in contrast to darkly pigmented Pamiris (Rychkov, 1969: 148–149). Were the Karasuk people really identical to Pamiris? And did they resemble groups with a high content of Andronovo component— Saka and Sauromatians? I.V. Perevozchikov (1971) noted

other geographically remote parallels to Karasuk people, namely, inhabitants of Central Iran buried at Sialk B*, аnd Tauri, representing the Kizil-Koba culture of Crimea. The search for those parallels was motivated by a hypothesis advanced by N.L. Chlenova (1971), postulating the affinties between the Karasuk people and Cimmerians.

A different direction of ties is revealed by comparing the Karasuk group with those relating to the contemporaneous Mongun-Taiga culture of Tuva. These people were later shown to resemble those of Karasuk craniometrically (Alekseyev, Gokhman, Tumen, 1987) while displaying only isolated cultural parallels with them (Chugunov, 1994; Poliakov, 2022: 240). In view of the attempts to localize the Karasuk homeland in Xinjiang (Alekseyev, 1961: 160; Rychkov, 1969: 158) it should be asked if the earliest published Bronze Age pre-Karasuk group from that region— Gumugou (Han, 1986)—displays Karasuk parallels.

Differences between Karasuk subsamples, specifically those between the Classic Karasuk group and that representing its “atypical”—Kamenny Log, or Lugavskoye—variety (Kozintsev, 1977: 15–29; Rykushina, 2007: 86), are poorly understood. G.V. Rykushina pointed to the “Andronovo” tendency of the culturally atypical group, whereas I wrote about its “Tagar” tendency, which, in essence, is the same. Is this the only craniometric difference between the two culturally distinct varieties of Karasuk? The spatial variation within the Karasuk people requires further study too: according to A.V. Gromov (1995; 2002: 103, 112–114), southern Karasuk groups resemble only the Andronovo populations of Kazakhstan and the Upper Ob, while those of northern Karasuk differ from them. Initially, Gromov ascribed this difference to Okunev admixture (1995), but later he questioned its existence (2002: 110, 115). Finally, the hypothesis about the Yeniseian affinities of the Karasuk language (Chlenova, 1969) raises a question as to whether a physical resemblance exists between the Karasuk people and the sole extant group speaking a Yeniseian language—Kets.

These questions can be approached on the basis of a cranial database, which has significally expanded in the recent years (this especially concerns the Andronovo samples), and with the help of modern statistical techniques.

Material and methods

The total number of male samples included in the analysis is eighty, and they represent the following cultures, stages, and regions**.

-

1. Karasuk culture, Classic variety (Rykushina, 2007: 93);

-

2. Karasuk culture, Kamenny Log variety (Ibid.);

-

3. Atypical Karasuk group (samples No. 4–7 pooled) (Kozintsev, 1977: 18–20);

-

4. Same, Northern group—Kamenny Log burials on the Karasuk River (Ibid.);

-

5. Same, Malye Kopeny III (after G.F. Debetz, unpublished) (Ibid.);

-

6. Same, Fedorov Ulus (after (Alekseyev, 1961)) (Ibid.);

-

7. Same, Eastern Minusinsk group—Lugavskoye (Beya) burials on the right bank of the Yenisei, south of the Tuba (after G.F. Debetz and V.P. Alekseyev) (Ibid.);

-

8. Karasuk culture, Northern group (Rykushina, 2007: 74)*;

-

9. Same, Southern group (data by Rykushina (Ibid.) and Gromov (1991, 1995), relating to samples No. 20–24 are pooled);

-

10. Same, Yerba group (Rykushina, 2007: 74);

-

11. Same, left bank group (Ibid.);

-

12. Same, right bank group (Ibid.);

-

13. Same, Khara-Khaya (Ibid.: 96);

-

14. Same, Tagarsky Ostrov IV (Ibid.);

-

15. Same, Kyurgenner I (Ibid.);

-

16. Same, Kyurgenner II (Ibid.);

-

17. Same, Karasuk I (Ibid.);

-

18. Same, Severny Bereg Varchi I (Ibid.);

-

19. Same, Sukhoye Ozero II (Ibid.);

-

20. Same, Arban I (Gromov, 1991);

-

21. Same, Beloye Ozero (Gromov, 1995);

-

22. Same, Sabinka II (Ibid.);

-

23. Same, Tert-Arba (Ibid.);

-

24. Same, Yesinskaya MTS (Ibid.);

-

25. Andronovo (Fedorovka) culture, Northern, Central, and Eastern Kazakhstan (for sources of data about Andronovo samples No. 25–36, see (Kozintsev, 2023b));

-

26. Same, Baraba forest-steppe;

-

27. Same, Rudny Altai;

-

28. Same, Barnaul stretch of the Ob, Firsovo XIV;

-

29. Same, Barnaul-Novosibirsk stretch of the Ob;

-

30. Same, Chumysh River;

-

31. Same, Tomsk stretch of the Ob, Yelovka II;

-

32. Same, Kuznetsk Basin;

-

33. Same, Minusinsk Basin;

-

34. Andronovo (Alakul-Kozhumberdy) culture, Southern Urals and Western Kazakhstan;

-

35. Andronovo (Alakul) culture, Northern, Central, and Eastern Kazakhstan;

-

36. Same, Omsk stretch of the Irtysh, Yermak IV;

-

37. Okunev culture, Khakas-Minusinsk Basin, Tas-Khazaa (Gromov, 1997);

-

38. Same, Uybat (Ibid.);

-

39. Same, Chernovaya (Ibid.);

-

40. Same, Verkh-Askiz (Ibid.);

-

41. Ust-Tartas culture, Baraba forest-steppe, Sopka 2/3 (for sources of data about samples No. 41–48, see (Kozintsev, 2021));

-

42. Same, Sopka 2/3A;

-

43. Odino culture, Sopka 2/4A;

-

44. Same, Tartas-1;

-

45. Same, Preobrazhenka-6;

-

46. Krotovo culture, Classic stage, Sopka 2/4B, C;

-

47. Late Krotovo (Cherno-Ozerye) culture, Sopka 2/5;

-

48. Same, Omsk stretch of the Irtysh, Cherno-Ozerye-1 (Dremov, 1997: 83, 85);

-

49. Pamiris, Goran, 13th–14th centuries (Rychkov, 1969: 202–205);

-

50. Same, Ishkashim, 14th–16th centuries (Ibid.);

-

51. Same, Wakhan, 15th–16th centuries (Ibid.);

-

52. Same, Rushan, 18th century (Ibid.);

-

53. Saka, Eastern Kazakhstan, 7th–4th centuries BC (Ginzburg, Trofimova, 1972: 121);

-

54. Same, Kirghizia, 7th–4th centuries BC (Ibid.: 130);

-

55. Sauromatians, Lower Volga and Southern Urals, 6th–4th centuries BC (Balabanova, 2000: 35);

-

56. Sialk, Central Iran, period VI, necropolis В, 8th century BC (the date is documented by A.I. Ivanchik (2001: 168) and I.N. Medveskaya (2013); measurements by G.F. Debetz, published by T.P. Kiyatkina (1968));

-

57. Tauri, Crimea, Kizil-Koba culture, 8th– 5th centuries BC (Sokolova, 1960);

-

58. Mongun-Taiga culture, Karasuk period, Tuva, pooled (Alekseyev, Gokhman, Tumen, 1987);

-

59. Same, Baidag III (Ibid.) (V.A. Semenov and K.V. Chugunov (1987) attribute the cemetery to the earliest stage of the Mongun-Taiga culture, when the funerary rite was closest to that of Karasuk culture; see also (Chugunov, 1994));

-

60. Gumugou, early 2nd millennium BC, Xinjiang (Han, 1986);

-

61. Kets (Gokhman, 1982) (samples No. 61–80 are recent);

-

62. Tobol-Irtysh Tatars (Bagashev, 2017: 218–219);

-

63. Baraba Tatars (Ibid.: 218);

-

64. Tomsk Tatars (Ibid.);

-

65. Chulym Tatars (Ibid.: 217);

-

66. Southern Khanty (Ibid.: 216);

-

67. Eastern Khanty (Ibid.);

-

68. Northern Khanty (Ibid.);

-

69. Northern Mansi (Ibid.);

-

70. Nenets (Ibid.: 220);

-

71. Selkups (Ibid.: 217);

-

72. Kyzyl Khakas (Ibid.: 219);

-

73. Beltir Khakas (Alekseyev, 1960);

-

74. Sagai Khakas (Ibid.);

-

75. Koibal Khakas (Ibid.);

-

76. Kachin Khakas (Ibid.);

-

77. Shors (Bagashev, 2017: 220);

-

78. Teleuts (Ibid.: 219);

-

79. Kumandins (Ibid.);

-

80. Tubalars (Ibid.).

craniologists. In cases where a sample had been studied or rearranged by several experts, the latest source is indicated— one from which the data were taken.

*Hereafter the Classic versus Kamenny Log (Lugavskoye/ Beya) cultural attribution of samples is not specified. The first reason is disagreement between archaeologists (Rykushina used the classifications by E.B. Vadetskaya, G.A. Maksimenkov, and P.M. Kozhin, whereas I employed those elaborated by M.P. Gryaznov and especially N.L. Chlenova). The second reason is that many samples include crania from burials of both cultural varieties.

The trait battery includes 14 measurements—cranial length, breadth, and height, minimal frontal breadth, bizygomatic breadth, upper facial height, nasal and orbital height and breadth, naso-malar and zygo-maxillary angles, simotic index, and nasal protrusion angle. Data were processed using canonical variate analysis, and Mahalanobis distances corrected for sample size ( D2 c ) were calculated. The distance matrix was subjected to cluster analysis and nonmetric multidimensional scaling. The CANON package by B.A. Kozintsev and the PAST package by Ø. Hammer (version 4.05) were employed.

Results

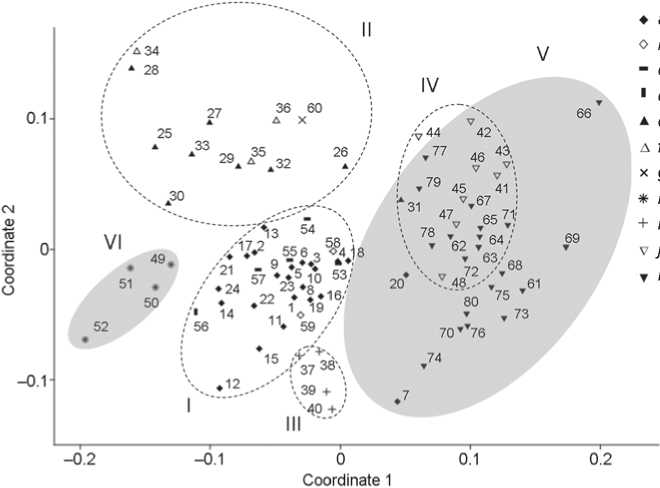

On the two-dimensional projection (Fig. 1), and on the dendrogram*, the Karasuk cluster (I) is in the center, surrounded by five others. It does not overlap with the Andronovo cluster (II) and is strictly intermediate between it and the Okunev cluster (III). Also, the Karasuk cluster is intermediate between the Pamiri cluster (VI) and the aboriginal Siberian supercluster, which consists of the ancient groups of Baraba (IV) and recent Western Siberian ones (V). The latter two clusters overlap nearly completely in the two-dimensional plot, although the dendrogram differentiates them better.

The Karasuk cluster includes all Karasuk samples except two—Eastern Minusinsk (No. 7) and Arban I (No. 20). Both fall within the recent Western Siberian cluster, Arban being likewise close to ancient Baraba groups. Also, the Karasuk cluster includes two MongunTaiga samples (No. 58 and 59), two representing Saka (No. 53 and 54), Sauromatians (No. 55), Tauri (No. 57), and the Early Iron Age series from Sialk B (No. 56). The latter, despite taking a peripheral position within this cluster, is very close to certain Karasuk groups such as those from Beloye Ozero (No. 21) and Yesinskaya MTS (No. 24). The Pamiri (VI) and the Karasuk (I) clusters

а b c d e f g h

Fig. 1 . Position of centroids of male cranial samples on the plane of nonmetric multidimensional scaling. See text for group numbers.

a – Karasuk; b – Mongun-Taiga; c – Saka, Sauromatians, Tauri; d – Sialk B; e – Fedorovka; f – Alakul; g – Gumugou; h – Pamiris; i – Okunev; j – ancient Baraba; k – recent Western Siberian.

I–IV – ancient clusters (shown by dashed contours): I – Karasuk; II – Andronovo; III – Okunev; IV – Baraba. V, VI – recent clusters (shown by spots): V – Western Siberian;

VI – Pamiri.

are separated by a gap—contrary to what Y.G. Rychkov (1969: 158–159) claimed, Pamiris are in no way identical to Karasuk people (for the single exception, see (Kozintsev, 2023a)).

The Andronovo cluster (II) includes all groups associated with this culture except one—from Yelovka II (No. 31), which is close to autochthonous groups of Baraba. The Fedorovka samples (No. 25–33) do not differ from those representing the Alakul variety (No. 34–36). The same cluster includes a group from Xinjiang (No. 60).

The comparison of two Karasuk samples formed by Rykushina on the basis of their cultural affiliation (Fig. 1), shows that the group representing Classic Karasuk (No. 1) is closer to the Okunev groups, whereas the Kamenny Log sample (No. 2) displays an Andronovo tendency (Fig. 1). My Atypical Karasuk group (No. 3), composed with the help of other archaeologists (see above), deviates from that representing Classic Karasuk not only towards Andronovans, but also towards aboriginal Western Siberian populations (see below).

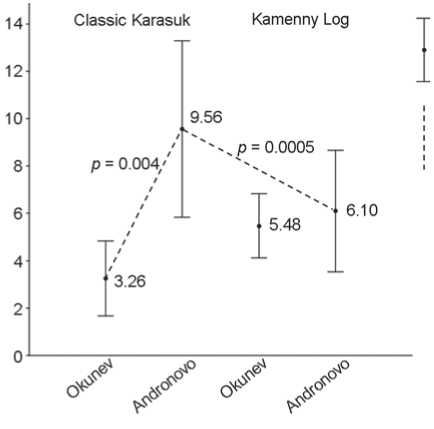

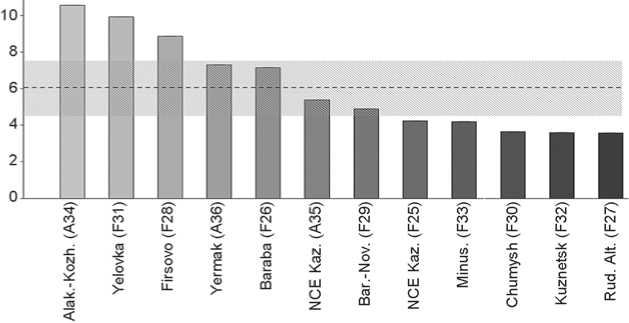

Let us specify the relative similarity between the Karasuk people and the twelve Andronovo groups, on the one hand, and four Okunev groups, on the other (Fig. 2). Average Mahalanobis distances with their standard errors for the Classic Karasuk group are as follows: 9.56 ± 1.08 versus 3.26 ± 0.79, respectively (Mann–Whitney U = 0, p = 0.004). Classic Karasuk people, then, are three times closer to the Okunev people than to Andronovo people. The Kamenny Log sample, on the other hand, is equally removed from both (Andronovo, 6.10 ± 0.74; Okunev, 5.48 ± 0.67, U = 22, p = 0.86). Which of the two Karasuk groups is closer to Andronovans? The answer is obvious—Kamenny Log (Wilcoxon paired samples test, W = 73, p = 0.005; same for my Atypical group: W = 78, p = 0.0005). As regards Okunevans, there is no difference between the two Karasuk groups: W = 10, p = 0.13 in both cases.

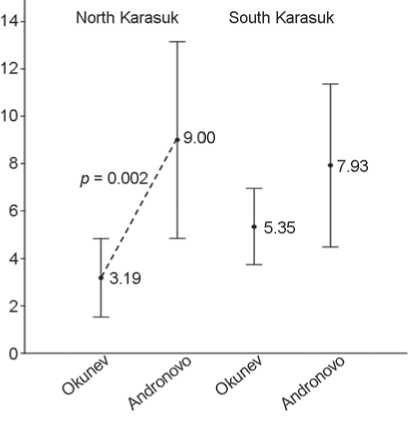

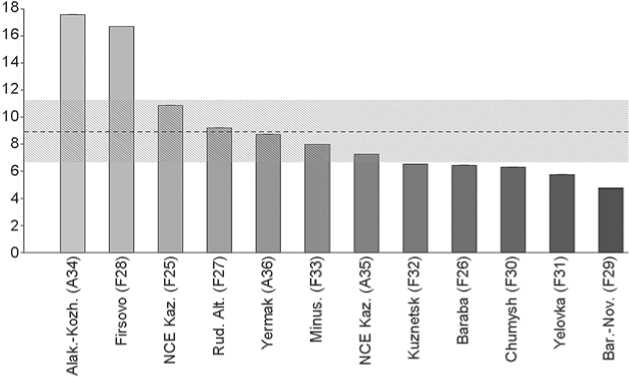

Let us examine the geographic variation within the Karasuk population (Fig. 3). The Southern Karasuk group (No. 9) is actually somewhat closer to Andronovans than is the Northern group (No. 8), but the difference is insignificant (7.93 ± 0.99 as against 9.00 ± 1.20, respectively; W = 63, p = 0.064). Nor is there any difference relative to Okunevans (5.35 ± 0.80 versus 3.19 ± 0.83, respectively; W = 10, p = 0.13). If Andronovans are compared with Okunevans, the Southern Karasuk group is somewhat closer to the latter, but the difference is insignificant again ( U = 8, p = 0.058). The Northern Karasuk group, by contrast, is significantly closer to Okunevans ( U = 1, p = 0.002). The Northern Karasuk people, therefore, are nearly thrice closer to Okunevans (3.19) than to Andronovans (9.00). In the Southern Karasuk people, the same tendency is observed, but the difference is small and insifnificant (5.35 versus 7.93, respectively).

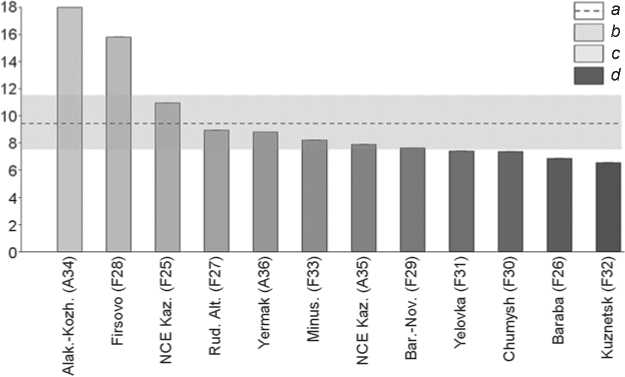

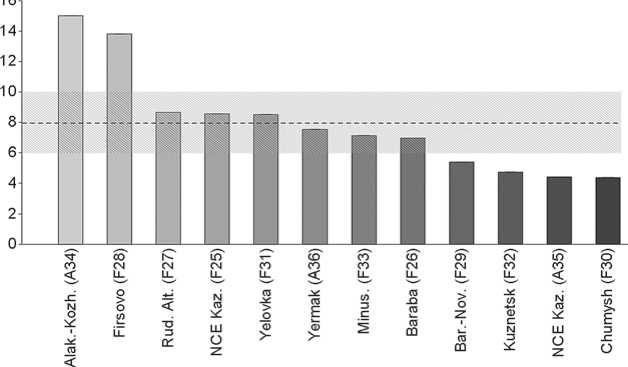

As we have seen, the Classic Karasuk group is on average much further from Andronovans than from Okunevans. Could certain Andronovo groups still be close to Karasuk people? As the plot (Fig. 4) shows, those least removed from Classic Karasuk are Fedorovka Andronovans of the Kuznetsk Basin, Baraba, and Chumysh. In the case of Kamenny Log (Fig. 5), those closest are Fedorovka Andronovans of Rudny Altai, Kuznetsk Basin, and Chumysh. The Northern Karasuk group is least removed from Fedorovka Andronovans of the Barnaul-Novosibirsk area, Yelovka, and Chumysh (Fig. 6); and the Southern Karasuk group, from Fedorovka Andronovans of Chumysh and Kuznetsk Basin, and from Alakul

а

b

Fig. 2 . Average Mahalanobis distances ( D2 c , shown by dots) of Karasuk samples (Classic and Kamenny Log) from those of Okunev and Andronovo.

a – average distances with standard deviations, b – significant differences.

Fig. 3 . Average distances of Karasuk samples (northern and southern) from those of Okunev and Andronovo. See Fig. 2 for explanations.

Fig. 4 . Distances between the Classic Karasuk sample and those of Andronovo.

See text for group numbers. A – Alakul, F – Fedorovka.

a – distance averaged across all Andronovo groups; b – 95 % confidence interval for the mean; с – minimal resemblance; d – maximal resemblance.

Andronovans of Northern, Central, and Eastern Kazakhstan (Fig. 7). In all four comparisons (see Fig. 4–7), then, one of the first three places is taken by Fedorovka people of Chumysh, and in three comparisons, those of the Kuznetsk Basin. Both regions border on the Minusinsk Basin in the west. Interestingly, among the samples especially close to Classic and Northern Karasuk, there are two Andronovo groups where the autochthonous Siberian tendency is the strongest— Baraba and Yelovka (see Fig. 1).

Eleven of the twelve parallels mentioned above relate to Fedorovka Andronovans. But because we have nine Fedorovka groups and three associated with Alakul, craniometry gives no reason to ascribe a special role in Karasuk origins to the Alakul people.

As concerns similarity with Classic and Northern Karasuk groups, even

Fig. 5 . Distances between the Kamenny Log sample and those of Andronovo. See Fig. 4 for explanations.

Fig. 6 . Distances between the northern Karasuk sample and those of Andronovo. See Fig. 4 for explanations.

Fig. 7 . Distances between the southern Karasuk sample and those of Andronovo.

See Fig. 4 for explanations.

those Andronovans closest to them are still closer to any Okunev group, with one exception (see below). In the case of Kamenny Log, the proportion is reverse, and with regard to Southern Karasuk people, the position of Okunevans is different: earlier ones (Uibat and Tas-Khazaa) are closer to them than are the closests Andronovans, whereas later ones (Chernovaya and Verkh-Askiz) are further.

The Ket connection is not supported by craniometry (see Fig. 1). Among the twenty modern Western Siberian groups, those closest to Karasuk people when averaged across their 24 samples are, in the decreasing order of similarity, Teleuts (No. 78), Sagai Khakas (No. 74), Tobol-Irtysh Tatars (No. 62), Kumandins (No. 79), and Nenets (No. 70), wehereas Kets (No. 61) take the 18th position—third furthest. Comparison with separate Karasuk samples does not reveal any noticeable parallels with Kets. The only exception is the sample from

Arban I, which is quite aberrant due to its eastern tendency. But Arban, too, is no closer to the Kets than to Tobol-Irtysh and Baraba Tatars, Kyzyl Khakas, and Teleuts.

Discussion

Results of the analysis lend no support to the idea that the sole ancestors of the Karasuk people were Andronovans. The main reason behind this fallacy was the paucity of data. Now we have twelve samples from various parts of the Andronovo distribution area, and not a single among them is closer to the Classic Karasuk group than are any of the four Okunev samples. Comparison with the Northern Karasuk group reveals one exception: Andronovans of the Barnaul-Novosibirsk area are somewhat closer to it than are Okunevans of Chernovaya. In other cases, the situation is the same as with the Classic Karasuk group. The situation with the Kamenny Log and Southern Karasuk is different (see above).

Another reason that could have led the researchers astray was the oft-cited fact that Karasuk is a post-Andronovo culture—a chronologically correct observation, which archaeologists sometimes interpreted following the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” logic. Actually, not only do the Karasuk and Andronovo clusters not coincide, but, moreover, they do not overlap: not a single one among the 24 Karasuk samples falls within the Andronovo cluster (see Fig. 1). Such a rapid and sharp transformation of physical type without visible reasons is absolutely impossible. Hence, it follows that Andronovans can be considered neither the sole nor even the main ancestors of Classic and Northern Karasuk people. To what extent do these two groups composed by Rykushina overlap is not clear. Anyhow, she arrives at the same conclusion (2007: 15–16).

In 1968, G.F. Debetz asked N.L. Chlenova, “And one more thing about the Okunev and the Karasuk people: why are they similar against all odds?” (Chlenova, 1977: 96). Today we know that they are not just similar, but also genetically related (Damgaard et al., 2018, Suppl. Mat.: 25). Results of craniometric analysis are in excellent agreement with the idea that Karasuk people are an outcome of the Okunev-Andronovo admixture. The map in Poliakov’s book (2022: 229), where the earliest Karasuk sites take a central position, being, in his words, “squeezed” (Ibid.: 310) between the Andronovo sites north of the Karasuk area and Okunev ones south of it, shows a striking resemblance with my plot (see Fig. 1). Apparently, the central area was the place where the most intense admixture and assimilation processes took place, resulting in the formation of the Karasuk group.

Archaeological data, however, suggest that the role of Okunevans in Karasuk origin was minor*, and that it can be traced only beginning from stage II, and only in the south of the Minusinsk Basin (Ibid.: 245, 291). According to craniometric data, by contrast, resemblance with Okunevans is the most distinct in the north of the Karasuk area. What could account for that? To all appearances, Andronovo migrants, who were geographically “squeezed” (see above) and experienced a shortage of women, rapidly mixed with aborigines (Okunevans), who were militarilly inferior to migrants and were assimilated by them. Owing to demographic disbalance, many native females remained outside the admixture process, whereas assimilation involved all. As a result, Okunev substratum affected the physical type of the newly formed Karasuk group, but not its culture**. In the north, the numerical predominance of aborigines over immigrants was insufficient to prevent invasion, but sufficient to maximize the substratal contribution to the admixed and assimilated Karasuk population of that area. In the south, the situation was different (see below). I used only data on male crania, but Rykushina (2007: 16), who studied the entire Karasuk material, concludes that the Okunev substratum had entered the Karasuk gene pool mainly through the female line. This should be expected under the assimilation hypothesis.

Denying the participation of Okunevans in Karasuk origins, Poliakov (2022: 245) refers to the absence of their cultural traces in the center of the Minusinsk Basin in the Late Bronze Age. But argumentum ex silentio cannot be considered critical, because before the Andronovo invasion, the Okunev distribution area had been much larger, and at the late stage Okunev burials became archaeologically “invisible” (Ibid.: 178). Also, assimilation could have taken part outside the Minusinsk Basin as well (Molodin, 1992), and could have involved relatives of Okunevans rather than themselves (Kozintsev, 2021).

*On the other hand, the Alakul migration, to which the critical role in this process is ascribed, turns out to be just one of the factors (Poliakov, 2022: 249), whereas no culture immediately ancestral to Karasuk can be found in other territories. In view of this fact alone, one might consider Karasuk origin a mystery, were it not for craniometric evidence.

**For the scarce archaeological evidence of the Okunev involvement, see (Lazaretov, Poliakov, 2008; Poliakov, 2022: 234, 238).

In the view of Gromov (1996; 2002: 112), the idea of a relationship between Karasuk people and Okunevans disagrees with cranial nonmetric data. This mainly concerns type II of the infraorbital sutural pattern (IOP II), the low occurrence of which sharply opposes Okunevans to both the Andronovans and the Karasuk people. The problem with this argument is that the heritability of these traits is unknown, and so is their distribution in admixed groups. Unlike the situation with measurements, an intermediate status of hybrids with regard to nonmetric traits cannot be taken for granted. A high frequency of IOP II in the Karasuk people could be due to dominance. This idea is indirectly supported by facts relating to certain admixed groups. The physical type of Uzbeks results from the admixture of “Mediterranean” aborigines of Southwestern Central Asia (in whom IOP II is normally rare), on the one hand, with Andronovans and Eastern Central Asian Mongoloids (the frequency of the trait is very high in both those populations), on the other. Uzbeks, too, display a high rather than intermediate frequency (Kozintsev, 1988: 84). It is likewise high in Pamiris (Ibid.), whose physical type is generally “Mediterranean” despite the likely contribution of Andronovans to their origin (Ginzburg, Trofimova, 1972: 304). The light pigmentation of the latter is recessive, which may account for the dark pigmentation of Pamiris. In short, I see no reason to regard IOP II as a key indicator in this situation*.

As regards the Andronovo component, Poliakov’s and Gromov’s conclusion is supported: the principal contribution belonged to a new wave of Andronovo migrants from the west rather than to local Andronovans of the Minusinsk Basin. Especially distinct are ties between the Karasuk people and Fedorovka Andronovans of the Chumysh and the Kuznetsk Basin. But still, in Classic and Northern Karasuk groups, those ties are less apparent than those with Okunevans. Craniometry provides no indications that Andronovans associated with the Alakul tradition had played a special role in Karasuk origins.

Rykushina’s Kamenny Log sample (No. 2) is much closer to Andronovans than is the earlier Classic Karasuk (No. 1), and the same is true of my Atypical Karasuk sample (No. 3)**. The probable reason is the third Andronovo migration wave—this time from the south, i.e., from Xinjiang via Mongolia, down the Upper Yenisei (Lazaretov, Poliakov, 2008; Poliakov, 2022: 311). According to Poliakov, it is from them that the Karasuk (in his terms, “Late Bronze Age stage 2”) people received the Shang dynasty bronzes, which were absent in the region at the earlier stage*. Interestingly, the Gumugou group (No. 60), which, according to the radiocarbon date, is earlier than Andronovo and shows no cultural parallels with it, is unambiguously Andronovo-like in terms of craniometry (see Fig. 1). Its closest parallels are Fedorovka Andronovans of Rudny Altai and the Kuznetsk Basin. This fact, along with absence of cranial similarity between Karasuk people and Pamiris, disagrees with the idea that Karasuk physical type is more ancient than the Karasuk population itself and had originated outside the Minusinsk Basin.

My Atypical Karasuk sample, as compared to the Classic Karasuk group, is shifted not only towards Andronovans but also towards Western Siberian natives (see Fig. 1). Because it was formed after the instructions by N.L. Chlenova, I should mention an observation made by I.P. Lazaretov (1996) about the Mongun-Taiga component in Chlenova’s Lugavskoye culture. Indeed, both Mongun-Taiga samples (No. 58 and 59) display a shift towards the autochthonous Western Siberian supercluster**, as does the Karasuk group from Severny Bereg Varchi I (No. 18), identical with them. The Karasuk sample from Arban I (No. 20), where certain burials show Lugavskoye features (Ibid.), even falls within this supercluster. The same applies to my Eastern Minusinsk group (No. 7), which includes crania from Lugavskoye— the cemetery eponymous for that culture (Kozintsev, 1977: 26–27).

A marked heterogeneity of the Karasuk population, which includes distinctly “eastern” individuals (one of whom resembles Glazkovo people of the Baikal area), has also been demonstrated by genomic analysis (Jeong et al., 2018; Karafet et al., 2018). At the same time, at least two of the Karasuk females display a European autosomal profile and alleles responsible for light eye color (Keyser et al., 2009). The evident reason is Andronovo legacy. Indeed, as noted above, Andronovo samples closest to those of Classiс and Northern Karasuk include two groups with the maximal expression of the “eastern” tendency— Baraba and Yelovka. Apparently, they are Siberian natives assimilated by Andronovans.

The fact that Saka, Sauromatians, and Tauri are members of the Karasuk cluster is understandable. Other members include early nomads of the Altai, Tuva, Mongolia, and the Aral region (Kozintsev, 2000). Apparently, admixture between Andronovans and Okunevans was but an episode in a chain of large-scale gene flow and admixture processes extending over large parts of Northern and Central Asia. Their repercussions are traceable in regions situated as far west and southwest of their center as Crimea and Iran (Sialk B), where the presence of Cimmerians is documented by both written and archaeological sources (Chlenova, 1971; Pogrebova, 2001). Incidentally, the date of Sialk B—the 8th century BC—coincides with the end of the Karasuk culture (Lazaretov, Poliakov, 2008)*. However, as regards its origin, those parallels are useless because of being late. The only exception are the Mongun-Taiga people— contemporaries of the early Karasuk people (Kovalev et al., 2008), differing from them culturally while being very similar craniometrically.

Could the Karasuk people have descended from those associated with the Seima-Turbino tradition, who had lived earlier? Regrettably, crania from Seima-Turbino burials at Rostovka (Solodovnikov et al., 2016) and Bulanovo (Khokhlov, 2017: 100, 293) are of little use, because they are few, poorly preserved, and problematic with regard to sex. Prima facie, those people could have been related

*A special analysis of the Cimmerian aspect of the Karasuk problem (Chlenova, 1971) is beyond the scope of this study. Possible Cimmerian connections, apart from those mentioned by Perevozchikov (1971), were discussed with regard to a cranium from a Novocherkassk burial in Ukraine (Kruts, 2002) and to those associated with the Chernogorovka culture of the Don Basin, also displaying Karasuk features (Batieva, 2011: 21). If it could be demonstrated that groups resembling Karasuk people really included Cimmerians, this would shed light on the Cimmerian versus Scythian controversy, because attempts at distinguishing these two peoples archaeologically have failed (Ivanchik, 2001: 281). At the same time, the cranial difference between the Karasuk people and those similar to them, on the one hand, and the pre-Scythian Chernogorovka population of Ukraine, cranially resembling Scythians, and Scythians themselves, on the other, is quite sharp (Kruts, 2002; Kozintsev, 2007). The fact that in a recent genetic study, Chernogorovka burials of the Dniester area are mentioned as Cimmerian without any qualification (Krzewińska et al., 2018, Suppl. Mat.: 8–9) shows the negligence with which certain geneticists handle the material they are using.

to Okunevans and, consequently, to those associated with Karasuk, as Chlenova (1977) believed. However, they are separated from Karasuk by a chronological gap. Even deeper roots of the aboriginal component within Karasuk could probably be revealed by comparison with Neolithic inhabitants of the Krasnoyarsk-Kansk forest-steppe and the Middle Irtysh (Kozintsev, 2021). Lack of physical resemblance between Karasuk people and Kets is all the more disappointing because Chlenova’s hypothesis has been supported by genomic analysis: among all modern Siberian populations, those genetically closest to Karasuk people are Kets (Flegontov et al., 2016).

Conclusions

-

1. The Karasuk population is unambiguously admixed. It had apparently originated on the Middle Yenisei by admixture between Okunev aborigines and Andronovo immigrants. The assimilation of the former by the latter resulted in a greater contribution of the Okunev substratum to the physical type of the early Karasuk people than to their culture.

-

2. In representatives of the Classic Karasuk culture and those living in the north of the Karasuk area, the Okunev component clearly outweighs that introduced by the Andronovo migration, probably because the aborigines were more numerous than the immigrants. In the Kamenny Log group and in the south of the Karasuk area, the proportion of the two components is closer to equal. The likely reason was the third wave of Andronovo migration, this time from the south, as archaeological criteria suggest.

-

3. If the Karasuk people originated in situ, as the hypothesis states, then the Andronovo component had evidently been introduced from the west by immigrants of the second wave rather than inherited from those of the first wave.

-

4. The Karasuk population could as well have originated elsewhere by admixture between Andronovans and some native Siberian group akin to Okunevans. Affinities with natives of the Baraba forest-steppe are discernible only in the minority of Karasuk groups.

-

5. Groups physically resembling those of Karasuk are the Mongun-Taiga people of Tuva, Saka of Kazakhstan and Kirghizia, Sauromatians, Tauri of Crimea, and those buried at necropolis B of Sialk (likely Cimmerians). All of them had evidently originated in the course of admixture processes involving Andronovo tribes and Siberian natives related to Okunevans.

-

6. It is not true that Karasuk people were indistinguishable from recent Pamiris.

-

7. Affinities between Karasuk people and Kets could not be supported by cranial analysis.

Acknowledgment

My heartfelt gratitude goes yet again to the late N.L. Chlenova for her invaluable help in the attribution of the cranial material.