The Pazyryk dwelling

Автор: Polosmak N.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Archaeological fi ndings suggest that the Pazyryk burial chambers made from larch logs replicated dwellings, being a key symbol of culture. Log structures were built on both winter and summer pastures. Parts of them were placed in graves as substitutes for entire houses. Their inner structure corresponded to that of the house. All artifacts in the graves had been used in everyday life, being intrinsically related to the owners’ earthly existence. Felt artifacts functioned in the same way in elite burials and in those of the ordinary community members, although their quality was different. Felt carpets decorating the walls of the Pazyryk leaders’ houses were true works of art, while those found in ordinary burials were simple and rather crude. The typical form of the late 7th–3rd century BC wooden burial chambers in the Altai-Sayan was pyramidal. In the Southern Altai, this form survived until the 1800s–early 1900s in Telengit aboveground burial structures.

Pazyryk culture, transhumance, funerary logwork, dwelling features, interior furnishing, felt carpets

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146836

IDR: 145146836 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.1.093-099

Текст научной статьи The Pazyryk dwelling

M.P. Gryaznov was the first scholar who pointed out that the Pazyryk people had permanent log buildings (1950: 59–60). He used the evidence from archaeological excavations revealing logworks in burials of early nomads, in particular in the 1st Pazyryk mound, which he explored. Gryaznov would have had even more grounds for such conclusion if he had known that it was not a robbers’ cut in the northern wall of the logwork in that mound, as he believed (Ibid.: 16, pl. III, 2), but a doorway. As V.P. Mylnikov established in our days, the burial chamber of the 1st Pazyryk mound was a part of logwork of a surface dwelling with a surviving doorway (1999: 29). The studies of recent decades have shown that the Pazyryk people reproduced the image of their homes in burial chambers. However, not all experts agree with this well-founded conclusion of archaeologists who personally studied the burial mounds of the Pazyryk culture. The newly discovered sites and their evidence compel us to readdress the topic of Pazyryk dwellings, which were, in our opinion, one of the key symbols of their culture. The purpose of the study is to prove the existence of log houses among the Pazyryk people.

Burial chamber as underground dwelling

After analyzing the evidence from the 1st Pazyryk mound, Gryaznov came to conclusion that “the Pazyryk tribe knew well the technique of building log houses, and undoubtedly lived in such houses” (1950: 59–60). The Pazyryk people led a nomadic lifestyle, which, according to Gryaznov, was confirmed by the entire set of grave goods containing no items that could not be used in nomadic life. Yet, in their places of wintering, they built sturdy houses, using larch-bark and birch-bark as roofing material. In addition, they could also have

had simpler dwellings of hut-type, covered with birchbark, bark of other trees, or possibly with felt (Ibid.: 60). S.I. Rudenko also believed that the Pazyryk people created dwellings of three types—houses made of logs, birchbark yurts, and felt yurts (1953: 78)—and were excellent carpenters: “This conclusion is supported by extensive burial chambers of the nobility of the Altai Mountains, discovered in large burial mounds we excavated…” (1960: 200). He believed that log houses were intended for the rich, while the poor lived in cone-shaped huts made of poles and covered with larch-bark (Ibid.). Rudenko also gave a detailed description of the internal structure of a Pazyryk log house, their furniture, felt carpets, and other household items, based on the evidence he discovered in burial chambers of large Pazyryk mounds (1953: 79– 89). According to Rudenko, in the natural environment of the Altai Mountains, it was easier to build houses of logs or poles than felt-covered dwellings. It is known from ethnographic evidence that only families with large herds of sheep could afford to produce the amount of felt needed to cover such dwellings. Representatives of such families were buried in the “royal” mounds (Ibid.: 79). Finally, according to V.D. Kubarev, who studied numerous ordinary Pazyryk burials, burial chambers of the Pazyryk people were imitations of their dwellings. The Pazyryk burial chamber, he wrote, was a larch-log cabin cut “with saddle joint with extending ends of logs” (this technique was used in the construction of dwellings, with the ends of uncut logs remaining at the corners), with the ceiling or roof made of one-sidedly hewn logs (with ends of the cover overhanging the walls of the logwork); covering the ceiling with sheets of birch- and larch-bark and pressing the sheets of birch- and larch-bark on the roof (or ceiling) with large boulders*; covering the gaps between wooden slabs with specially adjusted short poles and coating cracks in the walls and log-joints with clay; with the floor made of either wood slabs hewn on two sides or half-logs, covering floor and walls with felt and paving the platform for the logwork with pebbles (1987: 19–21; 1991: 27–29; 1992: 15–16). Thus, all leading scholars of the Pazyryk culture, who excavated both “royal” and ordinary mounds with surviving burial chambers (which is especially important), considered Pazyryk burial chambers to be the most reliable evidence of their well-developed housebuilding.

A different interpretation of Pazyryk burial structures was proposed by A.A. Tishkin and P.K. Dashkovsky (2003). From their point of view, “the logwork was not a typical dwelling of Early Iron Age nomads, who led a mobile lifestyle”, and therefore, “in graves of cattle breeders, there should have been made a semblance of a structure that had been common for most members of society for a long time. Most likely… this had to be a vehicle (wagon, cart, etc.) or portable dwelling such as a yurt” (Ibid.: 262). Referring to burial chambers of the Scythians and carriers of the Catacomb culture, Tishkin and Dashkovsky argued that “in many burial structures of ordinary Pazyryk people, the structure inside the grave indeed reflected the type of dwelling at the semantic level, yet in this case it was not a stationary dwelling, but probably some type of wagon. In addition, the wooden structure in the grave more closely resembles the base (box) or frame of a vehicle in terms of size and appearance. …The presence of a horse burial, combined with a typical structure inside the grave, shows the embodiment of the Pazyryk people’s idea of a funerary wagon (dwelling) for moving the dead to a distant afterlife, which was typical of Indo-European mythology” (Ibid.: 262–263). Those who have seen the Pazyryk burial chambers, built of larch logs, would agree that they least of all resemble the body of a wagon. The groundlessness of such statements is especially clear if we consider the recent findings of Mylnikov (1999, 2008, 2012; Samashev, Mylnikov, 2004). His thorough and comprehensive studies of Pazyryk wooden burial structures found in the Russian and Mongolian Altai and Kazakhstan allowed him to conclude that the people who left these structures possessed all professional skills and tools needed for constructing dwellings and utility buildings, and had extensive experience in constructing dwellings from logs. We fully share this opinion, and believe that all the burial chambers had real prototypes and were the reduced replicas of Pazyryk dwellings. As far as the “mobile lifestyle of nomads of the Altai Mountains” is concerned, their nomadic roaming was seasonal and occurred within a limited space, from winter to summer pastures (see, e.g., (Kubarev, 1991: 17–19; Polosmak, 2001: 19–20)). As S.V. Kiselev suggested (1951: 357), the Pazyryk people also built their stationary dwellings on summer pastures. Forest resources of the Altai Mountains could easily have provided timber for any needs of such construction.

The tradition of building log structures in the Altai-Sayan goes back to the Early Scythian period, or possibly even earlier. The “royal” Early Scythian burial mounds of Tuva suggest professional skills in wood-processing. Skillfully constructed cribworks were found in Arzhan-1. Double logwork, more perfect in structure than Pazyryk logworks, was discovered in Arzhan-2: its shape resembled a truncated pyramid; hewing of logs flat on the inside with rounded corners in the interior logwork finds direct parallels in structural features of interior logwork in the 5th Pazyryk mound (Mylnikov, 2017: 244)—the most recent structure from the chain of large Pazyryk mounds (Slyusarenko, Garkusha, 1999: 499).

Burial structures of the Pazyryk people were closely related to their earthly prototypes. Burial logworks were often assembled from individual elements of dwellings,

Fig. 1 . Doorway in the northern wall of the logwork. The 1st Pazyryk mound. Photo by M.P. Gryaznov. 1929.

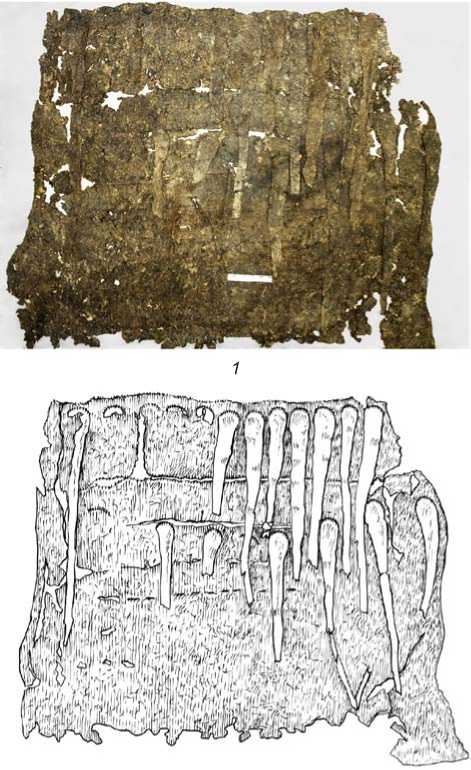

which in these cases served not only as building materials, but also as a symbol of the house (Fig. 1). It is likely that the Pazyryk people also had cone-shaped yurts*, covered with birch-bark sheets. In burials, birch-bark was used to cover the ceilings of wooden chambers**. We have not yet found any more reliable evidence on the existence of dwellings of this type among the Pazyryk people. However, we know for sure that they had structures made of poles. An indirect evidence is the presence of felt carpets with rows of ribbons sewn on them. One such carpet was found in a burial of an ordinary Pazyryk in mound 3 at the Verkh-Kaldzhin-II cemetery (excavations by V.I. Molodin); it covered a wooden bed (Molodin, 2000: 93). The trapezoid-shaped carpet was sewn of two pieces of dark brown soft and thick felt (Fig. 2). Its overall height was about 176 cm. The top edge, 164 cm wide, was neatly trimmed with woolen thread. The lower edge was unevenly cut off; its width was about 2 m. Long felt ribbons were sewn on the upper part of the cloth, in two rows. Each one was sewn only on the rounded edge; the ribbons tapered down and hung freely. The top row consisted of 14 ribbons (11 have survived), located at distances of no more than 2 cm from each other. The length of the longest surviving ribbon is 119 cm; a knot is tied at the torn end of one of the ribbons of the upper row. The bottom row of the same ribbons was sewn at a distance of about 59 cm from the upper line of the top row. Initially, there were probably also 14 of them; six sewn-on ribbons have survived. The whole item shows obvious traces of long-term use: many ribbons have been torn off from the cloth; ends of most of the ribbons have been torn off; felt has been worn out. The decoration pattern of this carpet, with two parallel horizontal rows of long ribbons sewn in the same way, is exactly the same as the famous large felt carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound (Rudenko, 1968: 56–57). Notably, ribbons cut from the same felt look natural on a simple dark felt from the ordinary burial, but they look like alien elements on the elegant carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound—simple and crude, these

Fig. 2 . Photo ( 1 ) and trace-drawing ( 2 ) of felt carpetcover. Mound 3 at Verkh-Kaldzhin II. Photo by K. Timokhin, trace-drawing by N. Khodakova .

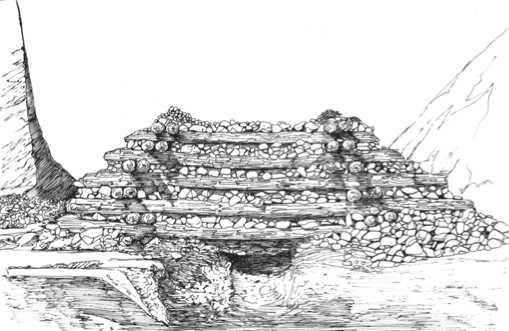

tightly sewn black ribbons only spoil the appearance of the item. They had a purely utilitarian purpose*. Black felt ribbons were sewn by the Pazyryk people in order to tie the carpet to the frame of poles. Several poles are known to have been found along with the carpet, suggesting that this was a part of the frame and covering of a summer dwelling. However, there is another explanation for these finds. Gryaznov and Rudenko disagreed about the purpose of the large felt carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound: Rudenko considered the carpet to be a wall decoration for a log house (1951: 113), while Gryaznov believed that it was a cover of a tent (see (Galanina et al., 1966: 99–100)). Objecting to the attribution of the felt carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound as the cover on the walls of a winter dwelling, Gryaznov noted that it had a sub-trapezoidal shape atypical of carpets (1960: 238). However, as it turned out, the outer logwork (rectangular in plan view, measuring 7 × 4 m at its lower level, and 2 m in height) of the 5th Pazyryk mound, which was additionally explored in 2017–2019, was made in a form of truncated pyramid. All its walls noticeably narrowed upwards and had sub-trapezoidal shapes in profile (Konstantinov et al., 2019: 418) (Fig. 3). The unusual configuration of the felt carpet from this burial mound is quite consistent with the shape of the walls of the burial logwork, which as we believe, was a part and a reduced replica of a real house. Pyramidal placement of logs, due to which the Pazyryk burial chambers looked like truncated pyramids, was first noted by Kubarev (1987: 20). Logwork not only for “royal” mounds, but also for ordinary small structures (Fig. 4, 5) throughout the entire area of the Pazyryk culture, including the Mongolian and Kazakh Altai, was made in this way. This tradition was rooted in the Early Scythian period. Pyramid-shaped wooden structures have been found not only in the Altai Mountains. An above-ground burial chamber in the Baigetobe mound at the Shilikty-3 cemetery in East Kazakhstan had the shape of a truncated pyramid (Toleubaev, 2018: Fig. 45, p. 175) (Fig. 6). Winter dwellings of the Pazyryk people might have had the same truncated pyramid shape, but this “pyramid” was much higher than the burial chamber. In order to understand fully the purpose of the carpet, we should turn to the earlier evidence from burial 5 in the Arzhan-2 mound. Its burial chamber was the same underground house—an imitation of an above-ground dwelling, like that of the Pazyryk people. In addition to its wooden structure, repeating in some distinctive and important details the burial chamber of the 5th Pazyryk mound, the burial logwork in Arzhan-2 had the shape of truncated pyramid (Mylnikov, 2017) (Fig. 7). In addition, elements of a special structure were found inside the chamber: thin

*The carpet was most likely an imported item, since the outfits of the rider and the goddess depicted on it have nothing to do with real clothes of the Pazyryk people.

transverse poles were attached to vertically installed posts along the walls, and were additionally tied to interior walls of the chamber. Posts were fastened in specially made square holes in the floor of the chamber along the walls. According to the leaders of the excavations, these elements served as basis for drapery of the walls with colored felt carpets (Chugunov, Parzinger, Nagler, 2017: 35). One more hollow, found in the center of the floor, according to Mylnikov, could have probably been associated with the erection of a frame structure, such as light tent-canopy, over the buried persons (2017: 243). In the “royal” burial of Arzhan-2, there was probably the structure for attaching the felt, piled, or woven carpets, which has survived in destroyed form. Such systems were set inside the dwellings of ancient nomads. We believe that in real life, in seasonal dwellings, carpets were not attached to the walls with bronze nails and wooden pegs, as the Pazyryk people did in burial chambers, but were hung on frames made of poles. Apparently, holes for the poles were found in burial 5 of the Arzhan-2 mound. In the 5th Pazyryk mound, elements of such a structure—poles*, corresponding in length to the height of the felt carpet, and the carpet itself were located in the horse compartment (Rudenko, 1953: 55, fig. 26). The felt carpet was too large for the burial chamber, and its walls were decorated with other felts (Rudenko, 1968: 66).

With this method of hanging, wall carpets (valuable textile products) remained intact, and could be reused and easily transported. Together with the rest of the belongings, they were carried from summer to winter pastures and back. This is why they ended up in the horse compartment, next to the parts of the cart on which they were transported. Only after the owner of the house had departed for another world were large felt carpets cut into pieces to required sizes and left forever on the walls of his last dwelling. The Gryaznov’s objections regarding the purpose of the carpet from the 5th Pazyryk mound also concerned the height of the item, 4.5 m. The scholar doubted that the Pazyryk people could have had such “huge mansions”. We do not have good knowledge about possible types of ancient dwellings. By way of example, it may be pointed out that the height of a urasa Yakut summer frame-dwelling, covered with birch-bark sheet panels, could reach 10 m (Sokolova, 1998: 71).

The structure of Pazyryk wooden dwellings cannot be reconstructed in all details. Burial complexes provide information only about some structural parts, but even this is extremely important, since the structure of the house

Fig. 3 . Burial chamber. The 5th Pazyryk mound. Assembly on the territory of the Anokhin National Museum of the Republic of Altai. Photo by V.P. Mylnikov .

Fig. 4 . Logwork. Mound 3 at Verkh-Kaldzhin II. Photo by V.P. Mylnikov .

Fig. 5 . Logwork. Mound 1 at Olon-Kuriyn-Gol-10 (excavations by V.I. Molodin, H. Parzinger, A. Nagler). Photo by V.P. Mylnikov .

Fig. 6 . Above-ground burial chamber in the Baigetobe mound at Shilikty-3, East Kazakhstan (after (Toleubaev, 2018)). Tracedrawing by E.V. Shumakova .

reproduces the worldview of the Pazyryk people (Baiburin, 1983: 14). For example, the entrance to the dwelling was made on the northern side, where in Pazyryk burials killed horses were usually located. The deceased were placed in the southern half of the

Fig. 7 . Logwork. Burial 5 of the Arzhan-2 mound. Photo by V.P. Mylnikov .

logwork; in the house, this was the sleeping place of the owners. If a male and female were buried in the grave, the body of the male was always placed next to the southern wall, and that of the female next to the male. If two males or two females were buried, the bodies of the older persons were placed closer to the southern wall.

Pazyryk burials contained furniture, which was absent from the Early Scythian “royal” burials. Various kinds of wooden beds were present in burial chambers, and larch hollowed woodblocks in burials of the nobility. In the epics of the Altaians, woodblocks are called “cradles” (Yamaeva, 2021: 188). This identification is confirmed by the fact that besides the noble deceased, children were also buried in hollowed woodblocks (Kubarev, 1991: 31, fig. 6). The burial of mummified bodies in a woodblock-“cradle” might have symbolized the return to the origins of life. Sometimes, in “royal” burial mounds, scholars have found beds*. Such wooden beds from the Great Katanda burial mound were sketched and described by V.V. Radlov: “At the bottom of the grave, there were two tables on four legs, directed from east to west. A skeleton with its head to the east lay on each of these tables… The tables were very carefully processed with an axe, but were not planed, and there was a rim about 1 inch high around each edge. The board, rim, and legs in the shape of truncated cones were made from a single piece of wood…” (1989: Pl. 6, fig. 8: 448). A similar bed, judging by this description, was discovered by Rudenko in the 1st Tuekta mound (Rudenko, 1960: 201, pl. LIV, 1 ; Mylnikov, Stepanova, 2016). The beds’ height and proportions were commensurate with burial chambers, not to mention the dwelling. Notably, in the yurts of nomads, there were also many wooden items, such as chests, beds, and tables (Dzhanibekov, 1990: 139–140), and the yurts of the Altaians and Telengits always contained wooden beds, in the complete absence of any other furniture (Toshchakova, 1978: 100).

Conclusions

The key symbol of the Pazyryk culture was not dwellings made of poles, not felt yurts, but permanent stationary buildings—their log houses. Larch burial structures of the Pazyryk people were the embodiment of their earthly dwellings and their eternal home. Unfortunately, the perfect mastery of house building in the Altai Mountains was subsequently lost. According to the conclusion of ethnographers, “only in the early 19th century did the Altai log yurt appear, which was a transitional type from a cone- shaped and cylindrical yurt to log cabin or house… It took decades for Altaian nomads to learn the building technique borrowed from the Russian peasants” (Ibid.: 96).

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out under the Project “Comprehensive Studies of the Ancient Cultures of Siberia and Adjacent Territories: Chronology, Technologies, Adaptation, and Cultural Ties” (FWZG-2022-0006).

Список литературы The Pazyryk dwelling

- Baiburin A.K. 1983 Zhilishche v obryadakh i predstavleniyakh vostochnykh slavyan. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Chugunov K., Parzinger H., Nagler A. 2017 Tsarskiy kurgan skifskogo vremeni Arzhan-2 v Tuve. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Dzhanibekov U.D. 1990 Ekho… Po sledam legendy o zolotoy dombre. Alma-Ata: Oner.

- Galanina L., Gryaznov M., Domansky Y., Smirnova G. 1966 Skifiya i Altay: (Kultura i iskusstvo skifov i rannikh kochevnikov Altaya): Putevoditel po zalam Ermitazha. Leningrad: Sov. khudozhnik.

- Gryaznov M.P. 1950 Perviy Pazyrykskiy kurgan. Leningrad: Izd. Gos. Ermitazha.

- Gryaznov M.P. 1960 Po povodu odnoy retsenzii. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, No. 4: 236-238.

- Hochstrasser-Petit C., Petit G. 2012 Berestyaniye pokryvala mogil. In Mir drevnikh yakutov. Yakutsk: Izdat. dom Sev.-Vost. Federal. Univ.

- Kiselev S.V. 1951 Drevnyaya istoriya Yuzhnoy Sibiri. Moscow: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Konstantinov N.A., Mylnikov V.P., Slyusarenko I.Y., Stepanova E.V., Vasilieva N.A. 2019 Zaversheniye polevogo dosledovaniya vnutrimogilnoy konstruktsii Pyatogo Pazyrykskogo kurgana. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXV. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 415-424.

- Kubarev V.D. 1987 Kurgany Ulandryka. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kubarev V.D. 1991 Kurgany Yustyda. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kubarev V.D. 1992 Kurgany Sailyugema. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Molodin V.I. 2000 Kulturno-istoricheskaya kharakteristika pogrebalnogo kompleksa kurgana No. 3 pamyatnika Verkh-Kaldzhin II. In Fenomen altaiskikh mumiy. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 86-120.

- Mylnikov V.P. 1999 Obrabotka dereva nositelyami pazyrykskoy kultury. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Mylnikov V.P. 2008 Derevoobrabotka v epokhu palemetalla (Severnaya i Tsentralnaya Aziya). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Mylnikov V.P. 2012 Investigation of wooden burial structures in the process of archaeological excavations. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 1: 97-107

- Mylnikov V.P. 2017 Tekhniko-tekhnologicheskiy analiz derevyannogo pogrebalnogo sooruzheniya iz mogily 5 kurgana Arzhan-2. In Tsarskiy kurgan skifskogo vremeni Arzhan-2 v Tuve. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 233-244.

- Mylnikov V.P., Stepanova E.V. 2016 Pogrebalniy stol iz kurgana 2 mogilnika skifskogo vremeni Tuekta. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXIII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 374-378.

- Polosmak N.V. 2001 Vsadniki Ukoka. Novosibirsk: INFOLIO-press.

- Radlov V.V. 1989 Iz Sibiri: Stranitsy dnevnika. Moscow: Nauka. Gl. red. vost. lit.

- Rudenko S.I. 1951 Pyatiy Pazyrykskiy kurgan. KSIIMK, iss. XXXVI: 106-116.

- Rudenko S.I. 1953 Kultura naseleniya Gornogo Altaya v skifskoye vremya. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Rudenko S.I. 1960 Kultura naseleniya Tsentralnogo Altaya v skifskoye vremya. Moscow, Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR.

- Rudenko S.I. 1968 Drevneishiye v mire khudozhestvenniye kovry i tkani. Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- Samashev Z., Mylnikov V.P. 2004 Derevoobrabotka drevnikh skotovodov Kazakhskogo Altaya (materialy kompleksnogo analiza derevyannykh predmetov iz kurgana 11 mogilnika Berel). Almaty: Berel.

- Slyusarenko I.Y., Garkusha Y.N. 1999 K voprosu ob otnositelnoy khronologii Pazyrykskikh kurganov. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. V. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 497-501.

- Sokolova Z.P. 1998 Zhilishche narodov Sibiri (opyt tipologii). Moscow: Tri L.

- Tishkin A.A., Dashkovsky P.K. 2003 Sotsialnaya struktura i sistema mirovozzreniya naseleniya Altaya skifskoy epokhi. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ.

- Toleubaev A.T. 2018 Rannesakskaya shiliktinskaya kultura. Almaty: Sadvakasov A.K.

- Toshchakova E.M. 1978 Traditsionniye cherty narodnoy kultury altaitsev (XIX - nachalo XX v.). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Yamaeva E.E. 2021 Mifologicheskiye osnovy altaiskogo eposa: Motiv “chelovek-ptitsa protiv odnoglazogo vraga” v kontekste interpretatsii materialov pazyrykskoy kultury. Kunstkamera, No. 3 (13): 184-193.