The Pisany Kamen rock art site on the Angara (marking the tercentenary of its discovery by D.G. Messerschmidt)

Автор: Zaika A.L.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The petroglyphs at Pisany Kamen on the right bank of the Angara, near Klimino, Kezhemsky District, Krasnoyarsk Territory, fi rst described by D.G. Messerschmidt in 1725, have been examined by many specialists. Most previous studies, however, were superfi cial, and the information they provided was unreliable and contradictory. To specify the site's location and to study the petroglyphs in more detail, using more advanced methods, the archaeological team from Krasnoyarsk Pedagogical University visited Pisany Kamen in 1999–2000. A topographic survey was carried out, and the petroglyphs were photographed and copied. Both previously known and new petroglyphs were recorded, showing animals, anthropomorphic fi gures in masks, and a separate mask. Results were compared with those recorded by Messerschmidt. The estimated dates of the site fall within a broad interval from the Early Bronze Age to the Late Iron Age (2nd millennium BC to 1st millennium AD). The pe troglyphs are relevant to various aspects of the ideology and material culture of the ancient popula tion of the region. Their further study will hopefully disclose the semantics of many images and assess their cultural and chronological attribution, relevant to the history of several modern groups of Siberia.

Messerschmidt, petroglyphs, angara, horsemen, iron age

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146884

IDR: 145146884 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.2.049-056

Текст научной статьи The Pisany Kamen rock art site on the Angara (marking the tercentenary of its discovery by D.G. Messerschmidt)

The petroglyphs of the Angara are notable for their diversity: images on rocky cliffs, coastal boulders and fallen stone blocks, separate slabs, and mini-sculptures. The Asian northernmost stone anthropomorphic sculpture is unique. The technique of execution is also varied: pecking, engraving, polishing, and tracedrawing with liquid or dry pigments of various colors. There are cases of combining different techniques when the pecked contour was rubbed and then painted over. Notably, despite the great number of other rock art sites in the region, this was the only one that attracted D.G. Messerschmidt’s attention about 300 years ago, and became a launching point for subsequent studies of the Angara petroglyphs. These were drawings on the Pisany

Kamen rock near the village of Klimovo. In the summer of 1725, Messerschmidt (1675–1735) undertook a boat trip along the Angara River from Irkutsk to Yeniseisk, and it was the final event of his long-term research journey in Siberia. During the trip, he was adding to his natural science collections; however, he was also interested in “antiquities”, and on July 8, 1725, he made a stop near the Pisany Kamen, “to examine the ancient images painted on the rock” (Putevoy zhurnal…, 2021: 378). Messerschmidt made sketches and descriptions of the petroglyphs, and determined the geographic coordinates of Pisany Kamen (Zaika, 2022). Judging by these sketches, he recorded images of two horsemen (Fig. 1) drawn with red ocher on a rocky surface, as follows from the description. After Messerschmidt, the site was visited by I.G. Gmelin, who did not find

Fig. 1. Drawings of the images at Pisany Kamen, made by D.G. Messerschmidt (Putevoi zhurnal…, 2021: 378).

anything else (Zaika, 2022: 30) except the same images of “two riders on horses, roughly painted with red paint” (Okladnikov, 1966: 7). Later, this rock art site was mentioned by G.F. Miller. He traveled through the site in 1738 and, unlike previous explorers, noticed only one image of a rider (Miller, 1999: 528–529).

Subsequent studies of the Angara petroglyphs took place almost 150 years later. In 1882, with the support of the East Siberian Department of the Russian Geographical Society, N.I. Vitkovsky carried out an archaeological survey along the Angara, almost from its source to its mouth. At Pisany Kamen, he recorded the previously unknown images of a horse and a deer, made with red ocher (Vitkovsky, 1889: 11). Notably, for more than 100 subsequent years, the Pisany Kamen images did not attract any attention from other researchers. One can only note the report made by geologist V.S. Karpyshev in the late 1950s (Zaika, 2022: 30). He carried out geological works at the rock, recorded an elk image on its surface, and briefly described it (Okladnikov, 1966: 104).

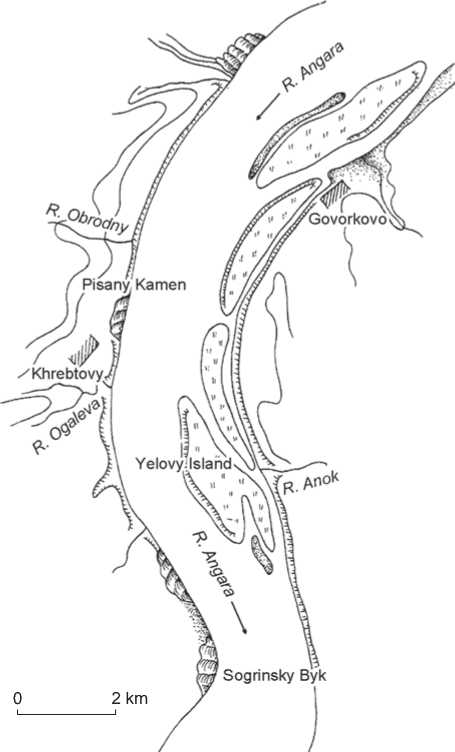

Judging by the information from the abovementioned researchers, the rock with the images was located “13 versts downstream the mouth of the Chadobets River, and 17 versts upstream the mouth of the Mura River” (Miller, 1999: 528), “between the villages of Klimovaya and Goltyavino” (Vitkovsky, 1889: 11), “between the Mura rapids and the mouth of the Kova River” (Okladnikov, 1966: 104). Only one coastal cliff known as Pisany Kamen is situated on the right bank in this section of the Angara, between the Obrodny stream and Ogaleva River, in the vicinity of the village of Khrebtovy, 7 km downstream of the village of Klimino (Karta…, 1984: 2), which description doesn’t contradict the Messerschmidt’s reports: “…on the right bank of the Tunguska (Angara River), about 2–2/3 old versts downstream the village of Klimovaya” (Putevoi zhurnal…, 2021: 378). For almost 200 years, all rock art studies in the region were focused exclusively on this site. Apparently, this was due, on the one hand, to its geographical name, Pisany Kamen (‘rock with images’), and on the other hand, to the lack of the relevant research in that period. In 1999–2000, a team from the Astafiev Krasnoyarsk State Pedagogical University carried out archaeological studies of the site in order to establish its location accurately and to clarify the ambiguous information about the images (riders, horse and deer, elk) (Makulov et al., 1999; Zaika, 2000). The general task included a more detailed and qualified study of the petroglyphs and a determination of the current state of the site’s preservation. The works were aimed at establishment of the site’s boundaries, a topographic survey of the locality, photographic recording and copying of the images, and their description.

Description of the site

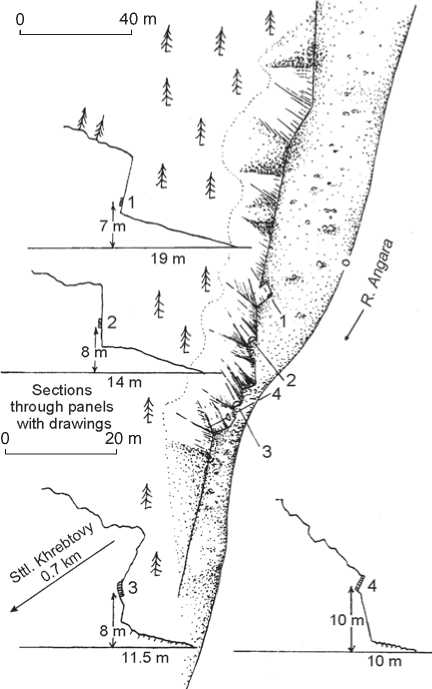

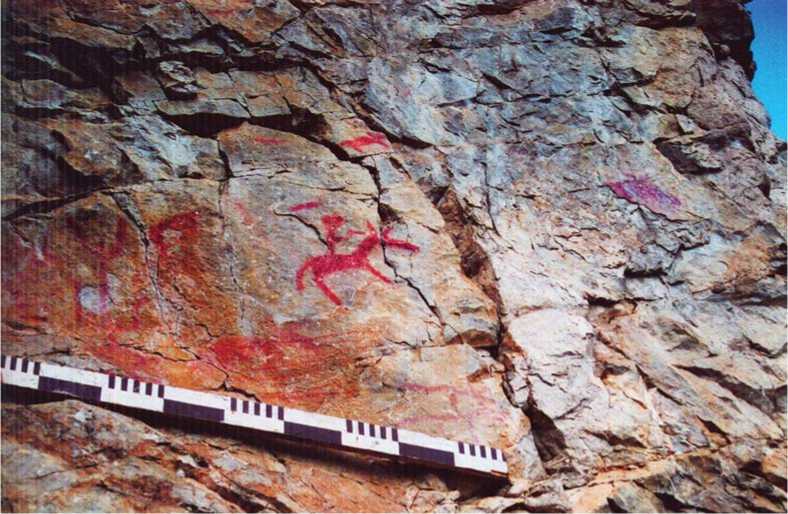

The Pisany Kamen rock art site is located on the right bank of the Angara River, downstream of the village of Klimino, Kezhemsky District, and 700 m northeast of the village of Khrebtovy, Boguchansky District of the Krasnoyarsk Territory (Fig. 2). This is a coastal cliff of whitish-gray limestones. It has sheer walls and a rather flat top, partly covered with taiga vegetation. The rock images are observed over a length of 50 m along the riverbed, on four steep cliff-faces (Fig. 3, 4); these were made with red ocher and black pigment. The images show animals, riders, anthropomorphic characters in the form of masks and masked figures. There are also barely identifiable images and fragments thereof.

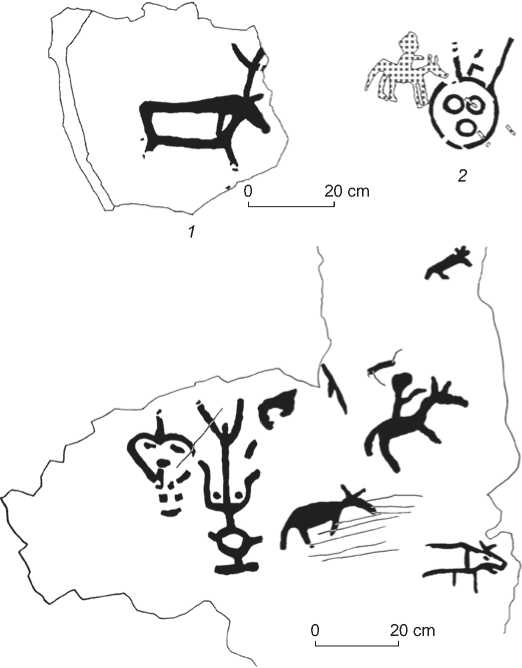

Panel 1 (0.6 × 0.6 m), facing southeast (az. 70°), is located 7 m above the water’s edge, in the northern part of the site. It shows a static contour image of a deer, rendered in a roughly realistic manner (Fig. 5, 1 ). The deer’s torso is shown in the form of an inverted isosceles trapezoid crossed in the front part by a vertical line; a hump is conveyed by a small protrusion. The neck is almost not distinguished; the realistically shown head is turned down, it is crowned with a vertical rod of horns with two lateral processes and a short line of ears. Straight limbs, widely spaced to the sides, are indicated by single short lines. The figure faces right. The ocher color is crimson.

Panel 2 (0.6 × 0.7 m) is located 17 m south of panel 1, at a height of 8 m from the water’s edge. It is vertical, facing southeast (az. 55°). In the center, a silhouette image of a rider is painted with light red ocher (Fig. 5, 2). The body is straight, wide, and short; one arm is extended forward, towards the head of the horse; the other arm and the legs are not shown. The rider’s head of hypertrophic size is rendered in the form of a rounded spot with a pointed top. The horse’s body has a dorsal deflection in the middle and a slightly paunchy belly; the neck is straight, raised up and stretched forward; the front and hind “valenki-shaped” limbs are straight, put slightly forward; the wide angular tail is raised up. The head is shown quite realistically, the fork of long ears is highlighted. The image of the rider partially (the “foot” of the front leg and the head of the horse) overlaps the rounded contour of the mask located to the right. The mask was drawn with black sooty dye. The eyes and mouth of the mask are rendered with three circles. It is crowned with two straight “antennas”. Between them, there is an angular line and oblique strokes of ocher, which was apparently used to represent the figure of the rider.

Panel 3 , 1.2 m high and 1.3 m wide, is located 20 m south of panel 2, at the same level. It is vertical and slightly concave, facing southeast (az. 60°). The drawings are made with red ocher, which color varies in a wide range: from scarlet to maroon (Fig. 6), suggesting that the images were made not simultaneously.

A silhouetted image of a rider, oriented to the right, is located in the middle part of the panel, in the area of a relatively fresh exfoliation of the rock’s crust. To the left, there is a large anthropomorphic image with a mask, rendered in a linear style; the image is shown with its head down (see Fig. 5, 3 ). The head part (facial mask) looks like a horizontal oval with short “outgrowths” at the sides (braids, ears?). It is crowned with a T-shaped pommel. To the left of the anthropomorphic image, a heart-shaped face

Fig. 2. Layout plan of the Pisany Kamen location.

Fig. 3. General southern view on the cliff with images.

Fig. 4. Topographic map of the rock art site.

Fig. 5. Copies of the images from panel 1 ( 1 ), 2 ( 2 ), and 3 ( 3 ).

Fig. 6. General view on panel 3 from the southeast.

is shown. Below and to the left of the rider, a silhouetted image of an ungulate animal (elk?) is shown. Stylistically, it looks similar to the horse, but with a larger torso and short neck and limbs. To the right of the animal, there is an incomplete, roughly realistic contour image of an elk, with a vertical division of the body, executed with red ocher, which changes maroon tones to pink under calcite streaks. Above the rider’s silhouette, there is probably a predator depicted; judging by the small size of its figure, it belongs to the Mustelidae family. A little to the side, 0.5 m to the right of the upper edge of the main composition, a realistic silhouette of the elk’s head turned to the right was identified (section 3a).

Panel 4 (2.5 × 3.0 m) is located 5 m southwest of panel 3, 10 m above the water’s edge. Unlike other petroglyphs, it faces northeast (az. 340°). The panel is relatively flat, but covered with cracks. It contains visible fragments of zoomorphic images, possibly ungulates. The rock frieze is hardly accessible; therefore, thorough examination of the images was not possible without special climbing equipment. Only the images in the lower right part of the panel, bearing the linear image of an animal in an inclined position, have been examined. The animal image shows proportionate torso and limbs; the neck and head are stretched forward and rendered with one straight line. The bifurcated ears are shown; the tail is not depicted. The animal species is hardly identifiable owing to the schematic style of the image. Below, a slanting ocher line is noted.

The site is in a critical condition. Rock panels are intensively destroyed both by natural processes (cracking and exfoliation) and anthropogenic impact (visitors’ inscriptions, lime burning in rock niches).

Discussion

Messerschmidt supplemented his description with an illustration showing two similar images of horsemen, located one above the other on adjacent panels, subdivided by a diagonal rock crack (see Fig. 1). The recent examination of the rocks did not reveal such a combination of horseman figures at this rock art site. Only solitary horseman images are represented in the compositions. Also, no signs of loss of fragments of these panels or adjacent stone blocks, which might contain another rider image, have been noted. Apparently, the researcher combined in his illustration the most striking images from different places on the rock, because later, G.F. Miller recorded only one rider image on one of the panels (1999: 528–529). Notably, until the early 20th century, the practice of “natural sketches” was widespread. Using this practice, researchers often combined images from various panels in a single graphic illustration at their own discretion (Belokobylsky, 1986: Fig. 12–15, 32–36).

Horseman images are present only in two parts of the rock art site (panels 2 and 3). They are located relatively close to each other (20 m between them), 8 m above the water’s edge. The panels face southeast, which does not contradict Messerschmidt’s illustration, as also the orientation of the riders (to the right) and the silhouette execution of the images (Zaika, 2022: 31). The horses are rendered in a relatively static pose, the tails and uplifted neck with ears are depicted; the bodies of the riders are straight, with only one hand extended forward to the neck of the horse shown; the rounded heads of the riders are depicted. As was mentioned above, the differences with modern data are insignificant, and observed only in particulars: the legs of the riders are not shown; the pairs of limbs of the horse on panel 2 are rendered with single lines. It seems that the researcher added “missing” details in his subjective desire to give the images a more naturalistic look. In any case, “it is necessary to note the high professionalism of D.G. Messerschmidt both as a scientist and as an artist, as he noticed the main features of rock images correctly” (Ibid.). These images and the nearby figures are not connected by a single idea; in one case (panel 2), this is evidenced by a sharp color contrast between the images and various stratigraphic levels of their position on the rocky surface; in the other case (panel 3), by various degrees of patination of the underlying rocky surface (the rider image was made on the area of a relatively fresh exfoliation of the rock’s surface).

The neighboring masked anthropomorphic image and the masks on panels 2 and 3 are typical of the Bronze Age figurative traditions of the Lower Angara (Zaika, 2012). The simple mask-face with a rounded black contour on panel 2 corresponds to the Early Bronze Age (Zaika, 2013: 155, pl. 129). Such masks are characteristic of the Tas-Khazaa figurative tradition of the Early Bronze Okunev culture of the Middle Yenisei. Two straight “antennas” are also typical of the faces of this type. These has been noted on the anthropomorphic image on the floor slab in burial 1 of the Tas-Khazaa cemetery (Lipsky, Vadetskaya, 2006: Pl. XVI) and on a number of rock images (Sher, 1980: Fig. 63, 116, 9 , 10 ). These similarities in the style and iconography of the images may be the result of intercultural contacts observable not only in petroglyphs, but also in other archaeological evidence from this period (Zaika, 2006a: 331).

The anthropomorphic figure depicted in an upside down position on panel 3 was likely made in the later period of the Bronze Age. Judging by the recent discoveries in the region, the head part of the image shows iconographic features close to the bronze mask found at Ust-Kata-2. During excavations of layer 1, a bronze plate in the form of a mask was found in a redeposited context. The suboval plate shows a T-shaped pommel, side eyelets, and a “neck”-handle at the base (Boguchanskaya arkheologicheskaya expeditsiya…, 2015: Fig. 415); the Pisany Kamen image shows similar iconographic features. The find was tentatively attributed to the Xiongnu-Sarmatian Period (Amzarakov, 2013: 205); although A.P. Okladnikov did not exclude the possibility that such cast items originated in the Scythian period, and rock images in the Late Bronze Age (1st millennium BC) (1978: 163, 183; 2003: 519–527). Anyway, it must be born in mind that the idea of a particular mythical image in a spiritual culture appears much earlier than its embodiment in the portable art. Consequently, this character was likely made on a rock in the Middle or Late Bronze Age. Spots on both sides of the chest mark the female principle of the image, the phallic process the male one. The upturned position of the figure can illustrate the symbolic death of this mythical “bisexual” spirit-deity.

The neighboring heart-shaped mask represents the image that had been popular in the rock art of the region since the Neolithic and was more common for the Bronze Age (Zaika, 2006b). Fragments of a narrow subrectangular contour under the “chin” can be interpreted as a conventional image of the torso or the neck-handle of the mask. In the latter case, this image is semantically close to the mythical character considered above and, accordingly, was made at approximately the same time. The incomplete contour image of an elk in the lower right part of the panel corresponds rather to the Middle Bronze Age (Klyuchnikov, Zaika, 2002). A more realistic contour image of a deer on panel 1 corresponds to the Early Bronze Age (Ibid.). Thus, the images of horsemen should be attributed to a younger period, the Iron Age (late 1st millennium BC to early 1st millennium AD).

Despite the different color shades of the horsemen images and the discrepancies in their iconography, these drawings are relatively contemporaneous. These were made by different authors, but in common figurative traditions. The horsemen show accentuated heads of exaggerated size, only one arm, stretched forward; the legs are not indicated. The horses are depicted in a “sudden stop” posture; they have straight limbs, thin necks, elongated narrowed heads, a pair of ears each, and long lowered tails. The semantics of various combinations of horsemen images with older anthropomorphic mask-and face-images is noteworthy, and the disproportionately large heads of the horsemen suggest certain connections with the masks. In any case, these assumptions require special studies.

In general, the subjects of the petroglyphs under consideration testify to the existence of certain forms of cattle breeding (for example, horse breeding) in the economy of the drawings’ author’s contemporaries. The recognizability of the image of the horse suggests a good knowledge of nature by the ancient artist, the roughly realistic manner of its depiction speaks of well-established artistic traditions. The “sudden stop” posture of the animals was typical of the Scythian-Siberian animal style; this may indicate a penetration of the tribes practicing the Tagar and Tashtyk cattle-breeding cultures from Southern Siberia into the taiga regions of the Angara (Makulov et al., 1999: 424). However, the Angara horsemen images do not show the legs of the riders, in contrast to the drawings of the southern neighbors. This manner of depicting riders is typical not only of the petroglyphs of the Angara region, but also of many rock images of the taiga zone of Eastern Siberia, which indicates the originality of the local figurative traditions.

The penetration of nomads into the northern taiga regions could not be accidental. This was apparently caused by various environmental, economic, and sociopolitical factors. To date, a representative set of horsemen images has been recorded at the lower Angara rock art sites (Klyuchnikov, Zaika, 2006). Half-length side-view images of horsemen similar to the characters at Pisany Kamen have been attributed to the Iron Age. Front-view images of riders have been associated with a later period. Full-length images of horsemen standing on the backs of horses, deer, or other real and imaginary animals dominated in late medieval rock art. Moreover, unlike the petroglyphs of Southern Siberia, where the rider’s image was often added to the earlier images of animals, the Angara rock art shows the opposite situation: the riding animal’s image was added to the bottom of an older anthropomorphic character. Thus, the image of the horseman and the associated ideas, which were borrowed and adopted in the spiritual culture of the taiga population of the lower Angara at the turn of the eras, did not lose their relevance and experienced a number of adjustments in the subsequent periods.

Notably, the powerful cultural impulse of the southern steppe cattle-breeding communities was reflected not only in the rock art, but also in other archaeological materials. In the altars and funerary sites, a series of metal items— both southern “imported” bronze artifacts and local iron replicas—was found. Most of them demonstrate the artistic traditions characteristic of the Scythian-Siberian animal style. Griffin images predominate; images of deer, feline predators, wolves, and camels are much less common (Zaika, 1999; Lomanov, Zaika, 2005; Drozdov, Grevtsov, Zaika, 2011). Moreover, at the level of Early Iron Age–Middle Ages layer, in a ritual depression at the Kamenka cult complex, an accumulation of horse cranial remains and limb-bones was found (SOAN-4362: 2295 ± 45 BP) (Zaika, Ovodov, Orlova, 2013). At the neighboring rock art site of Zergulei, realistic images of horses have been recorded (Klyuchnikov, Zaika, 2006). All this may indicate the emergence of not only local variants of horse breeding in the region in the Early Iron Age, but also cults associated with the veneration of horse; these practices were developed in the subsequent periods up to ethnographic modernity. For instance, the cult of the horse existed among the Lower Angara Evenki even prior to the arrival of the Russians; according to V.A. Tugolukov, the cult was borrowed by them from the previous Yenisei-speaking population (Assans and Kotts) (1985: 64). Notably, according to I.A. Chekaninsky, in the early 20th century, peasants of “Tungus origin”, who lived on the Lower Angara and its left-bank tributaries, traditionally kept wooden and iron images of horses in their barns and sheds. Moreover, in the recent past, Tungus people “shamanized using a horse” (1914: 71).

Conclusions

The Pisany Kamen images are the first archaeological site of rock art of the ancient population of the Angara, which became known to scientists thanks to the research by D.G. Messerschmidt. As the historiographic review of the regional studies showed, “this was not only the first discovery of rock art, but also the first step in the archaeological study of the Angara region, made by a famous scientist almost 300 years ago. Apparently, this did not vanish without a trace, but provoked further research into the ancient past of the Angara, which has not lost its relevance even today” (Zaika, 2022: 31).

The recent studies at the site have revealed both previously recorded and new images (animals, anthropomorphic figures in masks, and a separate mask). At present, estimated dates of the images at Pisany Kamen fall within a broad interval from the Early Bronze Age to the Late Iron Age (2nd millennium BC to 1st millennium AD). They testify to various aspects of the spiritual and material culture of the ancient population of the region.

The horsemen images recorded by Messerschmidt have been attributed to the Early Iron Age; these mark the interaction of southern pastoralists with the local taiga population during that period. Penetration of some elements of the economic activities of the steppe people (for example, horse breeding) into the taiga environment made certain adjustments to the material culture of the Angara people, and also led to changes in the worldview of the taiga tribes. The veneration of horse was reflected both in the materials of sacrificial complexes and in the rock art of the region, without losing its relevance until the ethnographically modern period.

Further studies of petroglyphs and other archaeological sites of the Angara region will provide a new insight into the topical issues of reconstructing various aspects of the life of ancient and traditional communities, determining the features of ethnocultural interactions in a wide chronological framework, and understanding various aspects of the ethnogenesis of the modern peoples of Siberia.

Список литературы The Pisany Kamen rock art site on the Angara (marking the tercentenary of its discovery by D.G. Messerschmidt)

- Amzarakov P.B. 2013 Predvaritelniye itogi arkheologicheskikh raskopok pamyatnikov Ust-Kata-1 i Ust-Kata-2 v zone zatopleniya vodokhranilishcha Boguchanskoy GES. Nauchnoye obozreniye Sayano-Altaya, No. 1 (5): 200-205.

- Belokobylsky Y.G. 1986 Bronzoviy i ranniy zhelezniy vek Yuzhnoi Sibiri: Istoriya idey i issledovaniy (XVII - pervaya tret XX v.). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Boguchanskaya arkheologicheskaya ekspeditsiya: Ocherk polevykh issledovaniy (2007-2012 gody). 2015 A.P. Derevianko, A.A. Tsybankov, A.V. Postnov, V.S. Slavinski, A.V. Vybornov, I.D. Zolnikov, E.V. Deev, A.A. Prisekailo, G.I. Markovski, A.A. Dudko (eds.). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Chekaninsky I.A. 1914 Sledy shamanskogo kulta v russko-tungusskikh poseleniyakh po reke Chune v Yeniseiskoy gubernii. Etnograficheskoye obozreniye, No. 3/4: 61-80.

- Drozdov N.I., Grevtsov Y.A., Zaika A.L. 2011 Ust-Taseyevskiy kultoviy kompleks na Nizhney Angare (kratkiy ocherk). In Drevneye iskusstvo v zerkale arkheologii: K 70-letiyu D.G. Savinova. Kemerovo: Kuzbassvuzizdat, pp. 77-85. (Trudy SAIPI; iss. VII). Karta reki Angara: Ot Boguchanskoy GES do ustya. 1984 Krasnoyarsk: Yeniseiskoye basseinovoye upravleniye puti.

- Klyuchnikov T.A., Zaika A.L. 2002 Animalisticheskiye izobrazheniya epokhi bronzy v naskalnom iskusstve Nizhney Angary. In Severnaya Aziya v epokhu bronzy: Prostranstvo, vremya, kultura. Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 63-65.

- Klyuchnikov T.A., Zaika A.L. 2006 Obraz vsadnika v petroglifakh Nizhney Angary. In Sovremenniye problemy arkheologii Rossii, vol. II. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 303-305.

- Lipsky A.N., Vadetskaya E.B. 2006 Mogilnik Tas-Khazaa. In Okunevskiy sbornik: Kultura i yeyo okruzheniye. St. Petersburg: Eliksis Print, pp. 9-52.

- Lomanov P.V., Zaika A.L. 2005 Khudozhestvennaya metalloplastika i petroglify Nizhnego Priangarya. In Drevnosti Priyeniseiskoy Sibiri, iss. IV. Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoyar. Gos. Ped. Univ., pp. 121-126.

- Makulov V.I., Leontiev V.P., Drozdov N.I., Zaika A.L. 1999 Noviye petroglify Nizhnego Priangarya (po itogam rabot 1999 goda). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografi i, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. V.

- Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 423-426. Miller G.F. 1999 Istoriya Sibiri, vol. 1. Moscow: Vost. lit. Okladnikov A.P. 1966 Petroglify Angary. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka.

- Okladnikov A.P. 1978 Noviye naskalniye risunki na Dubyninskom-Dolgom poroge (Angara). In Drevniye kultury Priangarya. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 160-192.

- Okladnikov A.P. 2003 Arkheologiya Severnoy, Tsentralnoy i Vostochnoy Azii. Novosibirsk: Nauka. (SO RAN. Izbranniye trudy).

- Putevoy zhurnal Danielya Gotliba Messershmidta: Nauchnaya ekspeditsiya po Yeniseiskoy Sibiri. 1721-1725 gody. 2021 G.F. Bykoni, I.G. Fedorov, Y.I. Fedorov (eds.). Krasnoyarsk: Rastr. Sher Y.A. 1980 Petroglify Sredney i Tsentralnoy Azii. Moscow: Nauka.

- Tugolukov V.A. 1985 Tungusy (evenki i eveny) Sredney i Zapadnoy Sibiri. Moscow: Nauka. Vitkovsky N.I. 1889 Sledy kamennogo veka v doline reki Angary. Izvestiya VSOIRGO, vol. XX (2): 1-31.

- Zaika A.L. 1999 Rezultaty issledovaniya kultovykh pamyatnikov Nizhney Angary. In Molodaya arkheologiya i etnologiya Sibiri, pt. 2. Chita: Izd. Chitin. Gos. Ped. Inst., pp. 11-16.

- Zaika A.L. 2000 O datirovke petroglifov “Pisanogo Kamnya”. In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. VI. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 282-286.

- Zaika A.L. 2006a Antropomorfniye lichiny Nizhney Angary v kontekste razvitiya naskalnogo iskusstva Azii. In Okunevskiy sbornik: Kultura i yeyo okruzheniye. St. Petersburg: Eliksis Print, pp. 330-342.

- Zaika A.L. 2006b Serdtsevidniye lichiny v petroglifakh Nizhney Angary. In Integratsiya arkheologicheskikh i etnograficheskikh issledovaniy. Krasnoyarsk, Omsk: Nauka, pp. 172-174.

- Zaika A.L. 2012 Face images in Lower Angara rock art. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, No. 1: 62-75.

- Zaika A.L. 2013 Lichiny Nizhney Angary. Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoyar. Gos. Ped. Univ.

- Zaika A.L. 2022 Pisaniy Kamen na Angare: K 300-letiyu otkrytiya naskalnykh risunkov D.G. Messershmidtom. In Izucheniye drevney istorii Severnoy i Tsentralnoy Azii: Ot istokov k sovremennosti: Tezisy Mezhdunar. nauch. konf., posvyashch. 300-letiyu ekspeditsii D.G. Messershmidta, V.I. Molodin (ed.). Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 29-31.

- Zaika A.L., Ovodov N.D., Orlova L.A. 2013 Sledy medvezhyego kulta na Nizhney Angare v epokhu rannego zheleza - srednevekovya (fragmentarniy obzor problemy). In Arkheologicheskiye issledovaniya drevnostey Nizhney Angary i sopredelnykh territoriy. Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoyar. krayeved. muzey, pp. 107-129.