The Role of Education and the Digital Era in Reducing the Economic Gap and Gender Inequality

Автор: Marija Ilievska Kostadinović, Gruja Kostadinović, Dejan Dašić, Goran Jeličić

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Review articles

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper explores the role of education and the digital era in reducing the economic gap and gender inequality. The main objective is to analyze how modern educational practices, combined with access to digital technologies, can contribute to the economic empowerment of women and the reduction of gender-based discrimination. The focus is placed on three interconnected areas: income disparity, access to digital technology, and educational inequality. Through a review of existing literature and statistical data, the paper highlights the importance of inclusive educational policies and digital literacy as key factors for improving women’s position in society and the labor market. Special attention is given to the need for equitable access to digital infrastructure, continuous support in education, and the creation of equal opportunities for participation in the digital economy.

Education, digital era, gender inequality, economic gap, women empowerment

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170210294

IDR: 170210294 | УДК: 371:004]:316.34 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-2-531-540

Текст научной статьи The Role of Education and the Digital Era in Reducing the Economic Gap and Gender Inequality

Digital technology and education are important tools in today’s society for lowering gender and economic disparities. Nonetheless, notable inequalities persist despite worldwide advancements in educational access, especially when considering the digital divide, which disproportionately impacts women and girls ( Lacković and Gašparić, 2022 ; Moraliyska, 2023 ; Jović et al., 2024 ). These disparities further widen the economic divide by preventing them from gaining the skills they need to engage in the digital economy.

Digital technology is an essential instrument for the development of literacy and skills and has the potential to increase access to education ( Gajić et al., 2020 ; Vučković, 2022 ). But basic literacy is also necessary to use digital technology, which presents another obstacle for many women and girls, particularly in rural regions where only 56% of people have internet access. Women’s economic empowerment and educational prospects are restricted by their inability to access digital resources ( UNESCO, 2022a ). Only 35% of graduates worldwide are female in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) professions, while only 26% are in AI and data science ( AlOqaily et al., 2025 ). Women’s economic potential are limited by this gender gap in digital skills and education, which also contributes to their underrepresentation in high-paying industries ( UNESCO, 2022b ).

Furthermore, just 38% of females in low-income nations complete lower secondary education, compared to 43% of boys, meaning that girls still fall behind their male counterparts in this regard. Particularly for girls from rural and marginalized groups, poverty continues to be one of the most important issues affecting their access to and completion of school ( Dessy, et al., 2023 ; Bonfert and Wadhwa, 2024 ). Initiatives to bridge the digital gap and empower women via education exist in spite of these obstacles ( Wadhai et al., 2024 ).

-

*Corresponding author: marija.ilievska@konstantinveliki.edu.rs

-

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Over the past century, women’s economic emancipation has advanced significantly ( Kakizhanova et al., 2025 ). In addition to actively engaging in the workforce, many women today hold leadership positions in businesses, governments, and international organizations ( Dašić, 2024 ). Nonetheless, gender disparities—which persist in the EU and other areas-represent significant expenses and lost chances for women as well as for businesses that do not fully use the potential of women and the whole economy. Support for female entrepreneurs promotes innovation and wider access to the labor market, boosts economic growth, and has a beneficial impact on gender equality ( Support for Female Entrepreneurs, 2024 ).

Disparities between men and women are measured by the Gender Inequality Index (GII) in three important areas: economic activity (labor force participation), empowerment, and reproductive health. A thorough picture of gender equality in a particular nation is provided by the meticulous definition of each of these aspects ( Duong et al., 2025 ). Africa and Asia continue to have the highest rates of gender inequality in the world, with relatively high values (~0.45–0.55) despite advances, highlighting the long-standing need for structural change (Table 1).

Table 1. Continental overview (1990–2023)

|

Continent |

GII in 1990 |

GII in 2023 |

Progress |

|

Africa |

~0.75 |

~0.55 |

Moderate decline |

|

Asia |

~0.70 |

~0.45 |

Significant decline |

|

Europe |

~0.45 |

~0.20 |

Strong improvement |

|

North America |

~0.50 |

~0.25 |

Moderate progress |

|

South America |

~0.65 |

~0.35 |

Moderate progress |

|

Oceania |

~0.65 |

~0.40 |

Gradual improvement |

Source: UNDP (2025). Global Gender Inequality Index (GII)

However, this essay will concentrate on three major areas of gender inequality-income disparity, access to digital technology, and education inequality-that have long-term effects on social and economic advancement. These aspects are interrelated and serve as the foundation for comprehending women’s access to information, their place in society, the job market, and chances for active engagement in the digital and economic domains.

Literature Review

The current academic community is interested in gender disparity in education and how it relates to digital change. The research by Ovacik (2025) examines how voice assistants and other digital technologies might unintentionally reinforce gender inequality by reproducing gender stereotypes through their functioning and design. The author highlights that women’s participation in the creation of digital tools and their digital education might be a crucial way to dismantle current hierarchies and promote equality in the digital age, based on study done in Istanbul among highly educated respondents. It also emphasizes the necessity of laws that support gender parity in the IT industry.

Pereira Souza and colleagues (2025) , who study the experiences of female students in Brazilian computer and communication technology schools, tackle a related problem. The authors note that the lower presence of women in technical sciences is a result of a number of ongoing obstacles in higher education, ranging from subtle forms of discrimination to feelings of loneliness and a lack of role models. According to their findings, even in technologically sophisticated environments, gender parity in STEM subjects will not be achievable until a safe and encouraging learning environment is established. However, Guo, Chen, and Zeng (2024) shed light on how digital finance may be used to support women’s economic empowerment. Analyzing data from China, the authors conclude that digital financial services provide women, especially those from vulnerable social groups, greater access to capital and greater bargaining power in the labor market. This indirectly reduces the gender pay gap and strengthens women’s economic autonomy, pointing to a strong link between the digital environment, education, and the reduction of gender inequality.

The economic gender gap may be closed in large part by education combined with gender-sensitive policies and digital technologies (Dašić et al., 2024a; Lunić, and Penezić, 2024). But technology advance- ments by themselves are insufficient; careful institutional support and a more comprehensive shift in society with regard to gender norms and educational practices are also necessary (Galindo and Rojas, 2025).

According to recent research, digital inequality is a pervasive issue that disproportionately impacts women and disadvantaged groups, rather than being a technical problem with regard to device or internet access ( Vuković et al., 2023 ; Dašić, 2023 ). Even when they have equal access, women utilize generative AI much less frequently than males, according to Otis and colleagues’ (2024) analysis of data from 18 research. The gender gap in technology continues to exist in the absence of empowerment and focused interventions, highlighting the need for policies that go beyond merely delivering technology. Disparities in digital knowledge and abilities are influenced by attitudes toward technology and availability to ICT resources ( Campos and Scherer, 2024 ).

The research by Miah (2024) supports this, pointing out that children from minority and lower-income families do worse academically because they have less access to digital resources and less opportunity to learn digital skills. Real inclusion requires both the capacity to utilize technology and the ability to overcome qualitative barriers, even though access to it may be a positive step. Products like mobile phones and internet access boost women’s labor market involvement, according to the UNDP/ ICRIER (2025) report from India. However, constraints such as gender norms, physical distance, and a lack of digital literacy still exist. The report also highlights the need for gender-sensitive infrastructure and educational policies to be directly related to digital inclusion.

In their analysis of 32 low- and lower-middle-income nations, which account for more than 70% of their total GDP, Rodríguez Pulgarín and Woodhouse (2021 ) employ ITU models to calculate the losses resulting from the gender gap in internet access. According to the findings, this disparity decreased their GDP by $126 billion in 2020 alone, and if the government does nothing, the total loss by 2025 would be $1.5 trillion. The authors suggest the REACT framework, which consists of rights, education, access, content, and objectives, as a comprehensive approach to empowering women and closing the digital divide via public policy and education. In addition to improving gender equality, investments in women’s digital inclusion would have a major positive economic impact. The authors urge governments to recognize this opportunity and implement policies that provide women with equal access to digital technologies. As a result, digital accessibility by itself is insufficient; in addition to physical access, digital skills investment, gender sensitivity, and locally tailored access are required. The digital realm runs the danger of exacerbating rather than decreasing current disparities in the absence of more extensive educational and social assistance ( World Bank, 2023 ).

In terms of economic disparity, according to Peck and Smith (2025) , women in the United States made just 83 cents for every $1 earned by males in 2023, which is only a three-cent improvement over the previous 20 years. The authors stress that structural hurdles, such as unequal organizational structures and restricted possibilities for development, are the primary causes of the pay gap’s delayed closure. IWPR’s Boushey (2024) supports this image, indicating a widening disparity: women’s average wages were only 82.7 cents for every dollar earned by males, suggesting that it may take decades to attain complete pay equality. This conclusion highlights the urgent need for more active public policy interventions.

According to a McKinsey research by Madgavkar and colleagues (2025) , up to 80% of the wage disparity may be attributed to career milestones including flexible work schedules, parental leave, and lower pay. The authors emphasize that women’s long-term career and financial success are significantly impacted by the institutional framework and employment policies. Through a thorough comparative analysis of executive salaries across 31 nations, Burns and colleagues (2025) demonstrate that up to 95% of the wage gap among executive-level employees can be explained by historical and cultural patterns, such as religious dogma, acceptance of gender inequality, and violence against women. This unequivocally demonstrates that the gender gap has both cultural and economic roots, bolstering the argument that addressing it requires tackling deeply ingrained social systems ( Dašić et al., 2024b ). The authors also stress that institutional compensation measures, such women quotas on boards and paternity leave legislation, have demonstrated notable results in closing the gap, but only when put into place in the context of a larger social revolution.

There are some outliers, such as Ert and colleagues’ (2024) findings showing female Airbnb hosts surprisingly make more money on average than their male counterparts. Despite the apparent promise, the authors caution about selection effects, pointing out that women tend to pick more appealing listings or better portray their offerings, which might obscure persistent systemic disparities. They contend that without well-designed profiles and services, this “earnings reversal” would not be feasible, suggesting a significant degree of result determination by individual actions as opposed to a decrease in gender disparity.

Inequality in Education

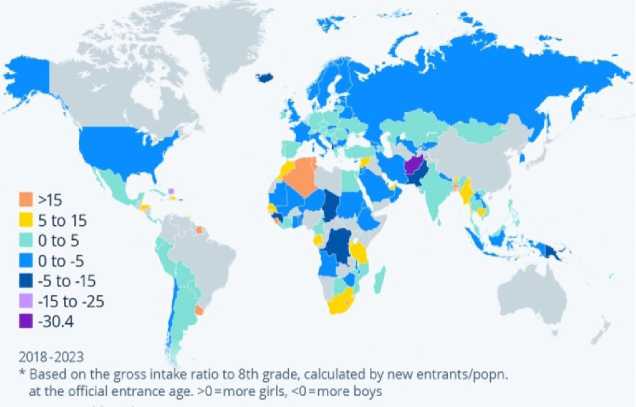

Girls currently get greater levels of education than ever before, demonstrating that mankind has advanced significantly in the area of education over the past 50 years, according to World Bank data. Even while these developments are unquestionably significant, gender equality in education has not yet been entirely attained, particularly in light of the ongoing regional differences. The lower secondary school completion rate, or the completion of basic education through the eighth grade, when pupils are normally between the ages of 13 and 14, is one metric used to evaluate gender disparity in the educational system. Gender gaps in certain countries are significant, according to an examination of the most recent data available for 169 nations and territories between 2018 and 2023 (see Figure 1).

According to Figure 1, Afghanistan had the biggest gender disparity favoring males, with lower secondary school completion rates for boys and girls in 2019 differing by -30.4 percentage points. Other nations with lower completion rates for females include the Democratic Republic of the Congo (-12.1 p.p. in 2020), Iceland (-5.2 p.p. in 2021), Albania (-8.4 p.p. in 2023), and Mauritius (-9.8 p.p. in 2023). It’s interesting to note that the data also show a reversal trend of gender disparity, with a far lower percentage of males than girls completing basic schooling. In 2023, the Cayman Islands saw the biggest gender disparity, with a 34.5 percentage point gender difference favoring females. Comparable trends were noted in Suriname (20.9 p.p. in 2021), Palau (21.1 p.p. in 2023), Sierra Leone (21.5 p.p. in 2021), and Tuvalu (29.3 p.p. in 2023) ( Fleck, 2025a ).

Figure 1. Who Reaches the End of Lower Secondary School?

Source:

On the other hand, 22 nations record lower secondary school completion rates for boys and girls that are roughly equal, within a ±1 percentage point gap. Four of these nations-Hong Kong, Azerbaijan, Peru, and Turkey-achieved full gender parity in this metric.

To fully comprehend the dynamics of gender disparity, it is necessary to highlight the methodological difficulties and the temporal lag in data availability. Afghanistan is a prominent example, where no data has been documented since 2019, even though the country’s well-known limitations on females’ access to school were put in place after the Taliban administration returned in 2021. In order to enable prompt reactions to detrimental trends in educational equity, this situation emphasizes the critical need for more frequent and transparent data monitoring ( Fleck, 2025a ).

Low-income nations continue to lag behind in terms of giving girls equal access to school, despite notable advancements achieved by lower-middle-income nations. Compared to 43% of males, just 38% of girls in low-income, primarily African nations had finished lower secondary education as of 2021. This indicates that there were only 0.89 females for every boy who finished basic school.

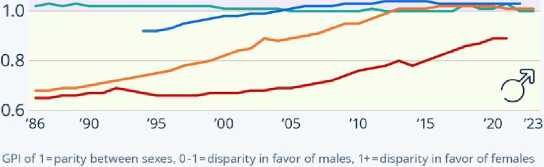

In the mid-1980s, the gender disparity in schooling was around 0.65 girls for every boy in low- and lower-middle-income countries, including Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, Vietnam, India, and others, according to World Bank data. Nonetheless, this ratio gradually improved and attained parity in the early 2010s. This equalization took place as early as 2004 in upper-middle-income countries, including China, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey, and the majority of Latin American countries (Buchholz, 2025).

In 2023, about 88–89% of children of the right age finished primary education worldwide, with girls continuing to be disproportionately represented among those who never went to school. About 75% of both genders’ children finished lower secondary school in that same year. The biggest disparity was once again shown in Afghanistan, where boys were more than 30 percentage points more likely than girls to complete eight years of education.

-

— Low income — Lower middle income

-

— Upper middle income — High income

*|,4 Global rates of completion

(in % of relevant age groups) Г^.

Male Female

1.2 Primary school 88.7 87.7 ”

Lower secondary school 74.6 74.8

Figure 2. Education Gender Gap Persists in Low Income Nations

Source:

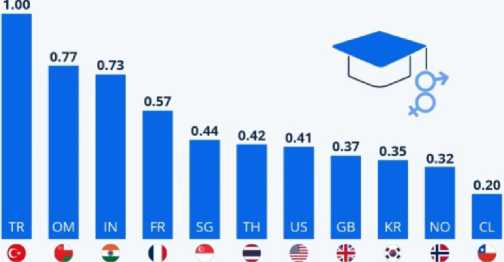

A gender gap still exists in the great majority of nations, albeit to differing degrees, despite ongoing attempts to increase the participation of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education. UNESCO keeps track of how many students are enrolled in STEM programs in higher education, which includes universities and vocational training. The Gender Parity Index (GPI), which has been used by the organization to examine this data, shows full gender parity at a score of 1, male advantage at a score between 0 and 1, and female advantage at a score above 1 ( Fleck, 2025b ).

Among the few nations where the proportion of women finishing STEM programs in higher education was equal to or even somewhat greater than the proportion of males are Turkey (2022) and Mauritania (2020, whose data is not included in the figure). The overall pattern indicates that the female-to-male ratios in STEM are generally lower in European nations; for instance, Germany recorded an index of 0.37, the UK 0.37, and Norway 0.32. However, a number of Asian nations had comparatively superior results (see Figure 3).

Graduates from tertiary education STEM programmes in selected countries (adjusted gender parity index)1

Latest available data (2021 -2023)

* STEM = science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

GPI of 1 = parity between sexes, 0-1=disparity in favor of males, 1+=disparity in favor of females

Figure 3. The STEM Gender Gap in Education

Source:

Inequality in Access to Digital Technologies

One major worldwide issue is still gender disparity in access to digital technology. In addition to internet access, the digital divide is also evident in the degree of digital literacy, with women generally having lower levels of digital literacy and being underrepresented in STEM professions. Their career prospects and capacity to fully engage in the contemporary digital society are both impacted by this discrepancy ( Dašić, G., 2023 ).

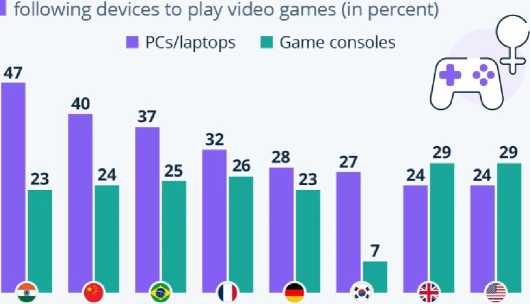

Compared to males, women who play video games have often been viewed as a minority since the 1990s. Although this is still mostly the case for gamers on PCs and consoles, the number of female gamers has been increasing significantly in several nations worldwide.

According to Statista Consumer Insights data, women in nations like Brazil, China, and India are particularly fond of PC and desktop gaming. That being said, women in the United States and the United Kingdom preferred console gaming. On average, 28% of female respondents in the 21 nations the survey examined stated they routinely play on computers, compared to 22% who claimed they do the same with consoles ( Fleck, 2025c ).

In the US, 64 percent of women and 58 percent of men reported routinely playing games on their cellphones, making mobile gaming particularly noteworthy in terms of gender dynamics. There are noticeable variations in terms of preferred genres. In 2024, casual games (reported by 39% of U.S. respondents), strategy games (34%), and action games (31%), were the three most popular game genres among women. The three most popular genres among American males were shooters (38 percent), action-adventure (45 percent), and action games (48 percent).

With 46% of respondents saying they frequently play on desktop PCs, Brazil had the highest percentage of PC gaming among the 21 nations studied overall. However, Mexico dominated the console gaming market, with 40% of respondents selecting that platform (see Figure 3).

Share of female respondents who regularly use the

IN CN BR FR DE KR GB US

1,013-5,118 respondents (18-64y/o) surveyed per countryJan.-Dec. 2024

Figure 3. State of Play: Female Gamers Around the World

Source:

According to a research by May et al. (2019) , the average woman had around half as many reputation points as the average guy on one of the most widely used IT platforms. This disparity is explained by the fact that, even when variables like membership duration and activity level are taken into consideration, women are more likely to ask questions and give fewer answers, which leads to less acknowledgment for their efforts. Antonio I. Tuffley (2014) also highlighted that women’s participation rates in digital technologies are much lower than men’s in developing nations, contending that for women to fully benefit from digital inclusion, technological access must be accompanied by social and political change.

Gender Pay Gap

On September 18, the United Nations observes International Equal Pay Day to draw attention to the continuous efforts to provide equal compensation for labor of equal worth. No nation has fully eliminated the gender wage gap despite these initiatives and advancements in women’s employment. Around the world, women still make around 80 cents for every dollar made by males.

The pay disparity still exists even in nations like the US, where women are now more likely than males to complete college. Ironically, at higher educational levels, this disparity widens even more. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) examined data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and found that the gender wage gap was around 30 percent for Americans with a college degree or above and 20.3% for those without a high school education (see Figure 4).

According to EPI, women make, on average, $4.50 less per hour than males do, even just after graduation ( Richter, 2023 ). Transparency in salaries, legally mandated minimum wages, and bolstering employees’ ability to collectively bargain for more compensation are important components in bridging this gap. However, the equitable division of household duties and family care between men and women is as crucial.

Average hourly wages in the United States in 2022, by gender and education

■ Men ■ Women □ Gender pay gap

Figure 4. Gender Pay Gap Widens With Education Levels

Source:

For instance, when compared to the prize money given to men’s teams, major event prize money still falls well short. Even if the prize pool grew from $30 million in 2019 to $110 million in 2023, as seen in Figure 5, there is still a significant gender gap in rewards. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there were 32 participating teams in 2023, up from 24 in 2019 ( Armstrong, 2023 ).

Although there is improvement, the United States provides a noteworthy illustration of how national football associations might momentarily close this gap. A “historic” arrangement was made there last year, wherein the U.S. Soccer Federation agreed to divide the entire prize money evenly between the men’s and women’s national teams in events in which both compete ( Pijetlović, 2024 ).

Figure 5. The World Cup Gender Pay Gap SOCCER

Source:

Conclusion

It is evident that digital transformation might have conflicting consequences on gender equality given the growing integration of digital technology into every aspect of contemporary life. On the one hand, women’s economic empowerment is made possible by digital banking, electronic platforms, and online labor marketplaces, particularly in situations when conventional restrictions still exist in the real world. According to some research, women who actively use digital tools and platforms can outperform males in some fields, including the gig economy or some types of entrepreneurship, and even earn comparable wages.

This beneficial dynamic is not ubiquitous, though. Digital technologies have the potential to replicate or even exacerbate gender inequality if they are not properly planned for and managed. As evidenced by gendered norms that influence how and why technology is used, algorithmic prejudice, and restricted access to digital resources, technological growth does not always translate into greater equality. Furthermore, even among the most educated members of society, there is still a gender wage difference, and economic outcomes are significantly shaped by factors including informal labor, caregiving duties, and institutional support.

Therefore, it is important to see digitalization as a socially conditioned phenomena that necessitates active involvement in labor, technology, and educational policy rather than as a neutral process. Combining access to education, empowerment via digital skills, algorithmic transparency, and the redistribution of unpaid care labor is crucial if the digital world is to become a place of inclusion rather than increasing division. Then, instead of being a band-aid or selected solution, the digital economy may actually be used to reduce the gender income divide.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.D.; methodology: D.D.; resources: M.I.K; G.K. and G.J., supervision: D.D.; writing—original draft preparation: D.D.; writing—review and editing: D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.