The role of international trade agreements in the economy of developing countries (the case of Nigeria)

Автор: Nagy Henrietta, Kposzta Jzsef, Neszmlyi Gyrgy Ivn, Obozuwa Omokheka Gregory

Журнал: Региональная экономика. Юг России @re-volsu

Рубрика: Фундаментальные исследования пространственной экономики

Статья в выпуске: 4 (22), 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The main objective of this paper is to give an overview on the trade agreements which are concluded by developing countries and to examine their contribution to the development of the economy and society. There are a number of such agreements, but it should be seen how much they really function and serve the quality of life of people as well as food security and safety. The aim of such agreements should consider the resources and needs of the parties for mutual benefits. There have been various initiatives in the countries of Africa especially to focus on and develop the agricultural sector, which has employed millions of people and has had significant role in keeping the population in the rural areas. However, regarding the bilateral or multilateral agreements, we should see that less progress has been achieved than expected. In this study the authors analyzed the situation in Africa, with special focus on Nigeria, to summarize the achievements and to list up some recommendations on future measures.

Trade agreements, developing countries, africa, nigeria, sustainable development, gatt, bit, wto

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149131288

IDR: 149131288 | УДК: 339.5(669) | DOI: 10.15688/re.volsu.2018.4.1

Текст научной статьи The role of international trade agreements in the economy of developing countries (the case of Nigeria)

DOI:

Trade agreements are undoubtedly veritable instruments through which a country can open its economy and market to commercial opportunities present in the ever dynamic and global market. Nigeria recognizes this fact, and, over the years, has entered into several of such agreements in a bid to strengthen and expand its economic frontiers. The thrust of these agreements has come in the form of reduction or removal of tariffs, quota / trade restrictions or concessions. It could also relate to exchange of goods and services between countries, all of which come mostly either as bilateral or multilateral trade agreements. Nigeria has been a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) since 1st January, 1995, and used to be a member of its predecessor-organization, the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT) from 18th November, 1960.

Nigeria’s GDP value represented 0.78 % of the world economy in 2015 that might be considered low. Nigeria’s international trade more than doubled in the 2003-2009 period, with exports rising to nearly USD 50 billion and imports to nearly USD 34 billion [50]. Nigeria is the 38th largest export economy in the world and the 125th most complex economy according to the Economic Complexity Index, ECI: -1.048 [43]. Nigeria exports 40 products with revealed comparative advantage (meaning that its share of global exports is larger than what would be expected from the size of its export economy and from the size of a product’s global market). In 2014, Nigeria exported USD 99 billion and imported USD 52.3 billion, resulting in a positive trade balance of USD 47.4 billion. Although crude oil accounts for nearly all the value of exports, trade continues to play an important role, with total trade (imports and exports) accounting for over 53 % of GDP [8] and tariffs being the main trade policy instrument. To encourage trade and investment, Nigeria provides a broad range of incentives most of which are tax or import-tariff related and apply to enterprises producing for export and domestic markets. Furthermore, to facilitate international trade, the Nigerian Export Processing Zone Authority superintends over eleven export processing zones (with additional ones under development).

The biggest trade partner of Nigeria is China. A range of bilateral agreements including the Agreement on Economic and Technical Cooperation, Trade Agreement, Agreement on Mutual Investment Promotion and Protection, and Double Taxation Agreement have been signed between China and Nigeria. According to the Chinese Embassy in Nigeria [12], bilateral trade with Nigeria stood at USD 10.8 billion, exceeding USD 10.0 billion for the first time. In 2012, bilateral trade was USD 10.6 billion, accounting for 5.3 % of China’s total trade with Africa, while in 2013 it was USD 13.6 billion and USD 180.0 million of direct investment, including assistance and technical cooperation. Nigeria’s trade agreements have either been at bilateral, multilateral (usually negotiated through the WTO), or regional level. This chapter will provide an overview on the agreements and their impacts on the economy and society of Nigeria.

The Antecedents

Since the early 1990s, many countries in Africa have made significant progress in opening up their economies to external competition through trade and exchange rate liberalization, often in the context of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank’s support programs. At the same time, with the creation or expansion of a number of regional trading arrangements in other parts of the world, several African nations have also worked towards this, resulting in the establishment or renewal of such trading arrangement in Africa too. The continent is now home to several regional trade agreements (RTAs) or trade blocs, many of which are part of deeper regional integration schemes.

While some RTAs have been revived, some other have been broadened and deepened. Whether regional/bilateral agreements are becoming a major feature of the global trading system (as opposed to a major preoccupation of trade negotiators) is not obvious [38].

Such trading arrangements are envisaged to foster trade and investment relation amongst member countries by removal of tariffs and other impediments to intra-regional trade flows. In some cases, the arrangement also aims at fostering common economic and monetary union amongst member states, as also a common currency. The success of these arrangements in fostering intra-regional trade has been diverse, with Southern African Community (SADC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), Cross Border Initiative, and West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) being the more successful ones [3].

International trade by its very nature requires careful planning and substantial investments, which can be recouped only over long periods of time. All long-term investments are highly sensitive to uncertainty, and foreign-trade-related investments doubly so for their outcomes may be affected by policy changes in several countries. The trade part of the international economic order can thus be understood as a set of policy commitments exchanged between and among countries in order to minimize policy-generated uncertainty and so to maximize the gains from trade. Orumgbe [35] also says that international trade system encourages specialisation which leads to greater gains in productivity and efficiency. It allows countries to concentrate their resources on producing goods they make best and importing goods which are more efficiently produced elsewhere but in the case of Nigeria it cannot be stated. What can be observed is that even if Nigeria has favourable conditions for agricultural and food production, the sector has not developed as it would have been necessary – considering the economic and social needs.

Africa’s place in the multilateral trading system has often received special attention, even though it has mostly focused on the contextual and factual analysis of the weakness of the continent’s contribution to global commercial transactions or the vagaries of the participation of African states in trade negotiations. There has been more than enough criticism suggesting that Africa is not making sufficient efforts to take part in international trade. On the contrary, African countries merit a spotlight on their significant progress to open up to trade.

However, an important question is how Africa can benefit from the opportunities created by international trade while minimizing the negative effects that go hand in hand with liberalisation. Africa’s inability to benefit from opening up to transactions can be explained by its integral position in international trade that offers little in the way of returns and produces little added value and wealth. Its status is that of a supplier of basic commodities and raw materials in very limited quantities, which restricts it to the bottom of the international value chains. In addition, due to the rushed liberalisation policies that African countries have experienced in the past, their efforts towards industrialisation, valorisation and transformation of raw materials and diversification were thwarted by the sudden, forceful competition of imported goods. Many countries continue to suffer from the narrowing of their political space as well as the loss of their sovereignty and control of their own economic and trade policy instruments created during this period [11].

In a case of a country rich in oil and natural gas, it could be assumed that it has well-operating economy and trade, by utilising its richness in natural endowments, it plays important role in the global economy. However, it is not true for many African countries, including Nigeria. It needs external assistance. By specialising in production and by trading with other countries, it is possible for countries to increase their incomes. Even though countries as a whole benefit from specialisation and international trade, some groups in society, providers of labour or capital, might lose. If international trade leads a country to specialise in producing goods that require lots of workers and little capital, such a specialisation increases wages (which benefits the workers), but decreases the income of the capital owners. The country, as a whole, benefits because the gain of the workers is bigger than the loss of the capital owners.

In addition to trade agreements in Nigeria, the chapter focuses on food security issues as well. Thus, it should be noted that availability of food alone does not seem sufficient to explain the attainment of food security in a country. Food can be available in a country because of effective agricultural policy; good harvest in a particular year or massive importation of food; or food handout (aid). Massive food import, particularly by developing countries, usually has negative effect on foreign reserves and causes budgetary hemorrhage [10], while food and which is sometimes used as an economic instrument in the service of political goal of the donor countries [22], may even discourage food production activities in the recipient countries; any country that needs massive food input or food aid before its citizens could feed would have only a short term solution to its food crisis but would not be food-secure for all times because the feeding of the people in that country will be dependent on the willingness and sometimes the ability of the external suppliers to supply. This is not to suggest that every country that has reason(s) to import food lacks food supply. On the contrary, some countries may and do import food to offset production shocks and cover the short-fall in domestic food supplies [25], encourage consumption of some food items or even assist the export trade of a particular target state with which they have bilateral trade agreements. Import of food by such countries may not necessarily be undertaken to solve any severe food shortage problem. To that extent, these countries are not food-insecure. The aim of this paper is to focus on the relationship between the trade agreements and the food security in Nigeria – providing there is one.

MAIN FOCUS OF THE CHAPTER

About Nigeria

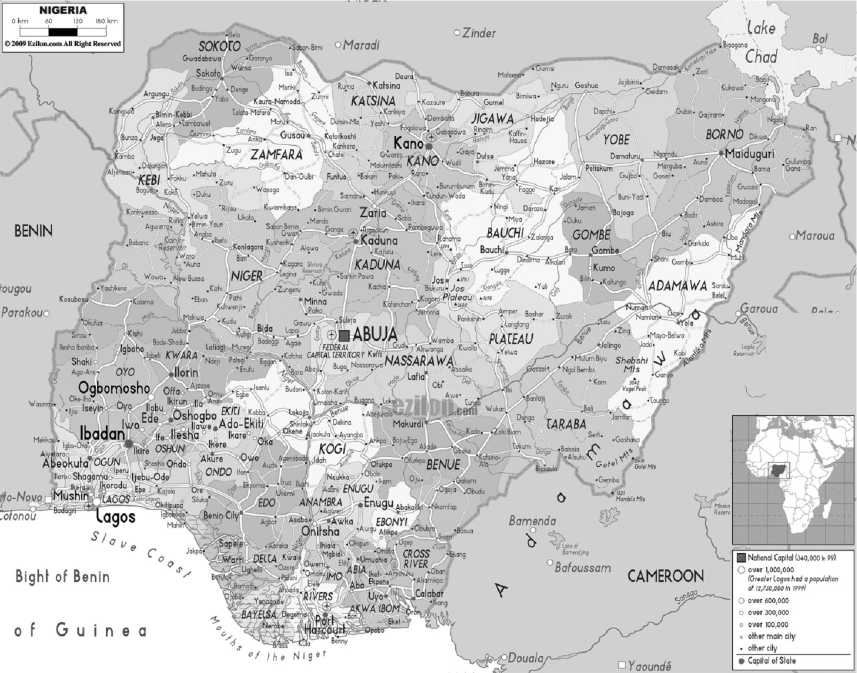

Nigeria is located by the Gulf of Guinea between Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Benin. Its territory extends to 923 thousand km2, and the huge economic potential makes it worthwhile to examine and discuss about. Being the federal republic, Nigeria comprises 36 federal states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Abuja (fig. 1).

The Federal Republic of Nigeria has the highest number of population in Africa totalled to 188 million inhabitants. The population has been rapidly growing. It was estimated that between 1911 and 1931 the Nigerian population grew from 17 million to 20 million – only 3 million in 20 years. By 1964 (four years after independence), the population was around 35.6 million people [37]. It means that in the course of a half decade Nigerian population duplicated, but from 1964 until now – during another half century – the population increased fivefold, and the rapid growth of population has still been continuing.

After all, it can be stated that Nigeria is the most significant country in West Africa. Its economy has

Note. Source: [30].

Fig. 1. Map of the Federal Republic of Nigeria

been developing dynamically for several years. In the past ten years, annual economic growth was about 7 %, which exceeded the average growth rate for Africa [18]. In 2014, Nigeria’s GDP increased by 7.1 % in spite of the decline of the oil prices. However, the decrease of the oil prices may worsen the conditions of the country in the short run, since the oil market prices are almost below the production costs. In 2014, the GDP in 2014 reached all time high USD 568 billion, while in 2015 it was USD 481.07 billion, and by this, the economy of Nigeria became the biggest in Africa. It was also pointed out that in 2014 Nigeria overtook South Africa by its economic performance, and in the meantime the author refers to the idea that Nigeria in the future might even take over the position of South Africa in the G20 group [29; 41].

The economy of Nigeria is the largest in West Africa and the second largest in sub-Saharan Africa, predominantly oriented to the production of agricultural products and crude oil. Nigeria’s economy – compared to the size of population – is not considered large. Before the country became independent in 1960, its economy was dominated by agriculture, and agricultural products overwhelmed in exports. However, in the early 1970s, the discovery of the oil fields fundamentally changed the structure of Nigeria’s economy. In 2014, agriculture accounted for about 24 % of the GDP and 70 % of employment, but contributed only about 2.5 % of export earnings. Crude oil and natural gas accounted for about 11.0 % of GDP, 95.0 % of export earnings, and 70.0 % of government revenue. Thus, the share of agricultural products in the total exports decreased significantly. The country has become oil exporting, which opposed it to the volatility of the oil prices. Due to the huge oil reserves and rich natural endowments, Nigeria was supposed to be a flourishing economy, but in reality, it is among the least developed countries of the world. Oil has brought several negative impacts on the country: it neither has resulted in any sustainable development, nor started any progress in infrastructure and social services. Moreover, corruption spread dramatically, and most of the population did not profit from the oil income. Government intended to spend some of the income on important investments, including industrial infrastructure development, however, due to the lack of competition, such actions resulted in the decrease of industrial production. Nowadays, the speed up in the industrial development can be observed through major political programs and private investments. However, poverty has not been moderated, and still causes big problems. The crisis caused by the dramatic decrease in the oil prices forced the politicians to review their former foreign trade policy and to diversify exports.

In spite of the fact that most of the area is arable, the majority of food the Nigerian people consume comes from imports. Beyond the rapid growth of the population, one of the major reasons of such import-oriented consumption is the rich oil and natural gas reserves, the exploitation and export of which provided the country with “easy cash” for the recent decades. Another reason is that the agricultural holdings are small and scattered, and farming is carried out with outdated tools and techniques. Modern and large-scale farms are not common. In a portrait book on Nigerian senator Ken Nnamani it was pointed out that the world spends around USD 3 billion per day on weapons and armies. The effect this huge amount of money could have if it is to be channeled to the improvement of human welfare can hardly be overestimated. However, defense budgets of almost all nations remain on the rise even at the risks of starvation of their citizens [26].

Political leaders and economic decision makers of Nigeria already recognized the necessity of development of food production and agricultural sector, which – contrary to the oil industry – would exercise a deep and positive impact on the rural society as well. Nigerian agriculture is being transformed towards commercialisation at small, medium, and large-scale enterprise levels [29].

The abovementioned economic growth has not been translated into creation of new workplaces or poverty alleviation. In 2016, unemployment rate was 13.3 % because the sectors driving the economic growth were not those with high job-creating potential. Oil and gas sector, for example, is a capitalintensive “enclave” with low employment-generating potential. The major policy issues are generation of employment opportunities, particularly among the young people, and inclusive growth. Thus, one of the major reasons of current economic and social problems in Nigeria is the lack of diversification. As the economy lacks diversification, agricultural sector lacks modernisation. To address this, the government is encouraging the diversification of the Nigerian economy apart from the oil-and-gas sector. It addresses underdeveloped infrastructure in the country and development of agricultural sector through modernisation and establishment of staplecrop processing zones, with the value chain model to provide linkages to manufacturing sector [4]. Furthermore, the principle of the modernist theory seems to be wrong in the cases of African countries and societies. For the development of these newly established independent states, the critical issue is whether it is possible to implement industrialisation in classical agricultural regions, and if so, in which extent. Models suggesting increasing rates of industrialisation might not be relevant for Africa [40]. Many governments failed to diversify the economy away from its overdependence on oil export. In parallel with increasing importance of oil-and-gas sector, there has been a general decrease of agricultural output. In Nigeria, this fact is observed in worsening foreign trade balance of agro-food sector. Because of this disproportional development, there is an increasing social tension between urban and rural regions of the country. If there seems no possibility to increase living standard of rural population concentrated in less-favoured regions of Nigeria, the authors have to forecast a rapid growth of overburdened cities (e.g., population of Lagos is over 10 million). This fact further aggravates criminal and environmental problems of big cities [51].

Boosting agricultural production involves targeted interventions and reforms, including technological innovation, productivity improvement, infrastructure development in agricultural production zones, commercialisation, input supply, and distribution systems. Specific interventions should include increase of land under farming, increase of use of improved seeds and fertilizers, enhanced cultural practices, mechanisation of agricultural production, and adoption of a value chain approach to boost agricultural production. All those measured should be complemented with improvements in infrastructure, particularly road transport, energy, irrigation, storage, and processing. Moreover, partnerships between private sector operators and associations of farmers should be developed, and long-term financing should be provided at a reduced cost to small- and medium-sized agricultural enterprises. Such measures are incorporated in the Agricultural Transformation Agenda of the Nigerian government.

The Transformation Agenda of the Nigerian economy for 2011-2015 [28] declared agriculture and food security among the seven growth drivers of the economy, which are agriculture, water resources, solid minerals, manufacturing, oil and gas, trade and commerce, and culture and tourism. The main task of the sector is to secure food and feed needs of the nation, by enhancing:

-

– generation of national and social wealth through greater export and import substitution;

-

– capacity for value-added approach to industrialisation and creation of employment opportunities;

-

– efficient exploitation and utilisation of available agricultural resources;

-

– development and dissemination of appropriate and efficient technologies for their rapid adoption in agricultural sector [28].

In November 2012, the Agricultural Transformation Agenda was adopted in which the government’s vision was set to boost agricultural sector in order to make Nigeria an “agriculturally industrialized economy” [1].

As it can be observed, there have been significant restructuring processes in Nigeria’s economy recently. In addition, one of the major priorities of the Nigerian government is to make the country attractive for domestic and foreign investors. Without foreign capital, economic growth cannot be achieved. Non-oil activities and investments are welcomed the most. In order to decrease the dominance of export, such sectors as tourism, telecommunication, trade, and industrial production have come into the frontline. Apart from oil, other products are not competitive on the market, and their export is limited. Consequently, Nigeria is now very open to regional integration and cooperation.

Bilateral Trade Agreements

Nigeria has bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Korea, the Netherlands, Romania, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates (the most recent). Agreements with Belgium, the Russian Federation, and the United States of America are being negotiated now [44].

Nigeria has comprehensive double taxation agreements with Belgium (1991), Canada (2000), China (2010), France (1992), the Netherlands (1993), Pakistan (1991), Romania (1994), South Africa (2009), and the United Kingdom (1989). These treaties apply to personal income, corporate income, capital gains, and petroleum profits [13]. As of 2011, treaties with the Czech Republic, Norway, the Philippines, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Korea, and Sweden were still being considered for finalisation and ratification. Agreement negotiations with Denmark, Gambia, Germany, New Zealand, Sierra Leone, and Switzerland are worthy of mention too. In case of Hungary, the first bilateral inter-governmental agreement on trade relations was signed with Nigeria in 1982, but in order to enlarge economic relations a new agreement on economic and technical cooperation was signed in 2016 (table).

Other Trade Agreements

World Trade Organisation

Nigeria is an original member of the WTO having ratified the WTO Agreement on December 6, 1994 (GATT document Let/1957, December 7, 1994). The Marrakesh Agreement establishing the WTO has been ratified, but in cases where its provisions have not been incorporated into Nigerian legislation, traders and investors are unable to invoke WTO provisions in domestic courts. However, appropriate legislations are being sorted out. Under the agreement, Nigeria has been active in the negotiations under the Doha Development Agenda thanks to its membership of several negotiating groups. The country is a member of the African Group, Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (ACP) Group, and the G-90 Group. In the agriculture negotiations, it is in the G-20 and the G-33 groups of developing countries, where it plays a prominent role. In the negotiations on agriculture under this agreement, Nigeria sought for improved market access, particularly into the markets of developed countries, along with reductions in domestic support and the elimination of export subsidies. As part of the G-33 group of countries, it also asked for flexibility in terms of market access and reductions in tariff escalations [48]. Under this agreement, it has enjoyed special and differential treatment, capacity building, and technical assistance.

Regional Agreements

African Union (AU) and African Economic Community (AEC)

Nigeria is a founding member of the African Union (AU). With the signing of the treaty (Abuja Treaty) by fifty-one head of states in June 1991, it gave birth to the African Economic Community (AEC), which came into force after required ratifications in May 1994. The aim of the AEC is to

Note. Source: [44].

Table

Bilateral investment treaties of Nigeria

|

Countries |

Date of the agreement |

|

Algeria – Nigeria |

January 14, 2002 |

|

Austria – Nigeria |

April, 8, 2013 |

|

Bulgaria – Nigeria |

December 21, 1998 |

|

Canada – Nigeria |

May 6, 2014 |

|

China – Nigeria |

May 12, 1997 |

|

China – Nigeria |

August 27,2001 |

|

Egypt – Nigeria |

June 20, 2000 |

|

Ethiopia – Nigeria |

January 19, 2004 |

|

Finland – Nigeria |

June 22, 2005 |

|

France – Nigeria |

February 27, 1990 |

|

Germany – Nigeria |

June 25, 1979 |

|

Germany – Nigeria |

March 28, 2000 |

|

Italy – Nigeria |

September 27, 2000 |

|

Jamaica – Nigeria |

August 5, 2002 |

|

Korea, Republic of – Nigeria |

March 27, 1998 |

|

Kuwait – Nigeria |

March 23, 2011 |

|

Netherlands – Nigeria |

November 2, 1992 |

|

Nigeria – Romania |

December 18, 1998 |

|

Nigeria – Russian Federation |

June 24, 2009 |

|

Nigeria – Serbia |

June 1, 2002 |

|

Nigeria – South Africa |

April 9, 2000 |

|

Nigeria – Spain |

July 9, 2002 |

|

Nigeria – Sweden |

April 18, 2002 |

|

Nigeria – Switzerland |

November 30, 2000 |

|

Nigeria – Taiwan Province of China |

April 7, 1994 |

|

Nigeria – Turkey |

October 8, 1996 |

|

Nigeria – Turkey |

February 2, 2011 |

|

Nigeria – Uganda |

January 15, 2003 |

|

Nigeria – United Kingdom |

December 11, 1990 |

promote economic, social and cultural integration in order to increase self-sufficiency with human resource mobilisation. This is with a view to ensure economic stability and peaceful relationship among member states. The mechanism to achieve this was to build strong Regional Economic Communities (RECs) (of which Nigeria belongs to the ECOWAS) and strengthen intra-regional integration. The roadmap which includes establishment of free trade areas in each REC, creation of continental custom union and African common market, and establishment of the African economic monetary union and parliament, is planned to be achieved by 2028 [5].

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

Nigeria has been a member of ECOWAS since it was created by the Treaty of Lagos in May 1975 with the objective of promoting economic integration among its member countries. In the quest to ensure speedy economic integration, the Treaty was revised in 1993 and set objectives for the creation of common market. Single currency (to be called ECO) was intended to be launched by the West African Monetary Zone (of which Nigeria is a member) by 2015. Unfortunately, introduction of a single currency was postponed till January 1, 2020 due to what it termed “non-fulfillment of financial responsibilities” by member countries. However, Amadou (2014) noted that Nigeria potentially portends a great impediment in achieving a single monetary union in West Africa because of the size of its economy compared to other countries in ECOWAS [5]. For instance, the entire West African Economy had the GDP of approximately USD 75 billion in 2013, while Nigeria alone had the GDP of USD 260 billion in 2013 (USD 510 billion, according to the US Department of State (2016). Nigeria is a major oil exporter as opposed to other West African countries [5].

Non-reciprocal Preferential Trade Agreements

ACP-EU Partnership Agreement (Cotonou Agreement)

The ACP-EU Partnership Agreement, signed in Cotonou on June 23, 2000, was concluded for a 20-year period, from 2000 till 2020. It was the most comprehensive partnership agreement between developing countries and the EU. Since 2000, it had been the framework for the EU’s relations with 79 countries in the ACP group. In 2010, ACP-EU cooperation was adapted to new challenges such as climate change, food security, regional integration, state fragility, and aid effectiveness. Before the Cotonou Agreement, Lomé Conventions (Lomé I – Lomé IV) were applied. However, important developments on the international stage and socioeconomic and political changes in the ACP group of countries highlighted the need for a re-thinking of ACP-EU cooperation. In accordance with the revision clause to re-examine the Agreement every five years, negotiations to modify the Agreement were launched in May 2004 and concluded in February 2005. The objective was to enhance the effectiveness and quality of the EU-ACP partnership and to reflect the recent major changes in international and ACP-EU relations. In March 2010, the European Commission and the ACP group concluded the second revision of the Cotonou Agreement. The second revision adapted the partnership to the changes which have taken place over the last decade, in particular:

– The growing importance of regional integration among ACP countries and in ACP-EU cooperation was reflected. Its role in fostering cooperation and peace and security, in promoting growth and in tackling cross-border challenges was emphasized. In Africa, the continental dimension was also recognized, and the African Union became a partner of the EU-ACP relationship.

– Security and fragility: no development could take place without a secure environment. The new agreement highlighted the interdependence between security and development and tackled security threats jointly. Attention was paid to peace building and conflict prevention. Comprehensive approach combining diplomacy, security, and development cooperation was developed for situations of state fragility.

– ACP partners faced major challenges if they were to meet the Millennium Development Goals, food security, HIV-AIDS, and sustainability of fisheries. The importance of each of these areas for sustainable development, growth, and poverty reduction was underlined, and joint approaches for the cooperation were then agreed.

– The EU and the ACP claimed climate change as global challenge and considered it as the major subject for their partnership. The parties committed to raise the profile of climate change in their development cooperation, and to support ACP efforts in mitigation and adaption to the effects of climate change.

– The trade chapter of the Agreement reflected the new trade relationship and the expiry of preferences at the end of 2007. It reaffirmed the role of the Economic Partnership Agreements to boost economic development and integration into the world economy. The revised Agreement highlights the challenges ACP countries are facing to integrate better into the world economy, in particular the effects of preference erosion. It therefore underlines the importance of trade adaptation strategies and aid for trade.

– More actors in the partnership: the EU had been promoting a broad and inclusive partnership with ACP partners. The new agreement clearly recognized the role of national parliaments, local authorities, civil society, and private sector.

– More impact, more value for money: this second revision was instrumental in putting in practice the internationally agreed aid effectiveness principles, in particular donor coordination. It would also untie the EU aid to the ACP countries to reduce transaction costs. For the first time, the role of other EU policies for the development of the ACP countries was recognized, and the EU committed to enhance the coherence of the policies to this end [19].

Nigeria and the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA)

In July 2014, ECOWAS Heads of State endorsed the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the African Union and the European Union. This trade agreement was expected to give rise to the institution of a Common Free Trade Area (CFTA) by 2015, thereby extending the African Growth and Opportunity Act by fifteen more years and serve as a strategic response of Africa to the WTO negotiations.

At the beginning, most of the African countries received the idea with high antipathy and even refused to sign it. It happened at the second EU-Africa summit in Lisbon, where the main objective was to encourage the African countries to sign new trade agreements by December 31,

2007 in accordance with the Cotonou Convention of 2000 winding up the 1975 Lomé accords. They claimed the EPAs as straitjacket and refused the idea of the complete liberalisation of trade. They did it despite the fact that the WTO had insisted that these preferential arrangements should have been dismantled or replaced by trade agreements based on reciprocity, claiming that this was the only way African countries could have continued to enjoy different treatment [39].

Abdoulaye Wade, the President of Senegal in the interview published in Le Monde in 2007 expressed the African opinion in sharp words, like “Europe expects Africa to voluntarily bow its head under the axe of executioner” [39]. At the same time, other African politicians accused the EU that it wanted to divide the developing world to the Least Developed Countries (LDC) and non-LDC countries by the EPA. After all, the EPAs aroused wide public concern. Social movements and trade union organisations in Africa were mobilised against them. Such a revolt bore fruit: the summit ended in failure. The president of the European Commission (that time: José Manuel Barroso) was forced to back down and accept the African countries’ call for further discussions [39].

Since the very beginning, Nigeria refused to be a signatory of the Agreement. Olusegun Aganga, the Minister of Industry, Trade, and Investment of Nigeria, speaking at an extra-ordinary session of the Conference of African Union Ministers of Trade in Addis Ababa in 2014, said the trade liberalisation deal with the EU would have a long-term negative impact on the continent’s efforts towards industrialisation and creation of jobs [17]. There is serious concern on the part of Nigeria because of the fear that it will replace the existing non-reciprocal Cotonou agreement between the EU and Africa, which allowed African countries access to the EU market without any reciprocal action from Africa. Under the new regime, the EPA will only allow trade preferences for African goods if Africa also provides the EU unbounded access to its markets. Under the agreement, Africa will remove 80 % of import tariff on goods coming from the EU. Furthermore, the EU also expects Africa to remove restrictions on export of unprocessed raw materials and promote liberalisation in other areas such as investment and services [15].

With effective and rigorous implementation of strategic blueprints for domestic manufactures coupled with drastic infrastructural development, it will not only ensure increased production but also alternatives to the most populous nation in Africa and improved quality occasioned by the healthy competition that will emanate therein. The perfect case experienced in the telecommunication industry. Gambia, Nigeria, and Mauritania are the only three countries who are still to sign the EPA. It will be interesting to see how the EPA between the EU and West Africa influences the region.

Future: Vision 20:2020

Nigeria’s Vision 20:2020 provides the framework for the national development strategy, which focuses on the diversification of the economy and poverty reduction, to be driven vigorously by the private sector by creating incentives and conditions to attract trade and investment. The objective of Vision 20:2020 is to place Nigeria among the top-20 economies in the world by 2020. The core elements of the strategy are modernisation of agriculture, rehabilitation of infrastructure, and development of the power sector (National Planning Commission, 2009).

According to the National Planning Commission [27], the strategy is being implemented through three medium-term development plans, which would require economic growth by 14 % per year from 2009 till 2020. The projection is at this rate to attain minimum GDP of USD 900 billion and annual per capita income of above USD 4,000, estimating that the population would have reached 193 million by 2020 and 289 million by 2050. One of the four thematic areas identified in the first plan is the productive sector that revolves around seven sub-sectors: agriculture and food security; oil and gas; manufacturing; small and medium enterprises; solid mineral and steel development; culture and tourism; and trade and commerce. The overall goal is to change to a service-based economy by 2018. Hence, the critical approaches are support of non-oil exports, increase of utilisation of preferential trade arrangements, and development of Nigeria’s participation in international trade negotiations. Specific sectoral priorities and targets, including donor support, are identified in the National Implementation Plan [50].

The government recognises that for trade and investment to thrive provision of the legal framework and removal of institutional and practical barriers are required (as provided for by the Foreign Exchange (Monitoring and Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1995 and the Nigerian Investment Promotion Commission (NIPC) Act, 1995, including tackling corruption, social and economic instability, and applying the rule of law). Also, Nigeria recognises the fact that its products need to be of high quality to be able to compete favourably on the international market. Hence, one of the country’s major regulatory trade agencies, the Standard Organisations of Nigeria (SON) in partnership with several donors, has been receiving technical assistance and capacity building in the area of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards [23] and capacity building for private and public-sector organisations in the area of food export [31; 32].

Furthermore, in a bid to boost the gains of a rapidly growing economy with respect to trade, Nigeria presented its trade and productive-capacity-related needs at the August 2010 Session on Aid for Trade of the WTO Committee on Trade and Development [49]. Seven areas for support were identified, namely: (i) trade policy advocacy, (ii) trade policy development, (iii) enhancing the competitiveness of supply capacity, (iv) compliance support infrastructure and services, (v) physical infrastructure, (vi) legal and regulatory framework, and (vii) trade facilitation and trade-related financial services. However, after rigorous and regular consultations with development partners, the Government of Nigeria decided to streamline the seven categories of activities into three broad areas of support for trade and productive capacity. These are: (i) mainstreaming trade into national development strategies, (ii) enhancing trade competitiveness, and (iii) institutional and human resource capacity development [50]. This made the focus and strategies of Vision 2020 in terms of trade more concise and precise to pursue.

Tripartite Free Trade Agreement (TFTA): An Example for Efficient Initiative

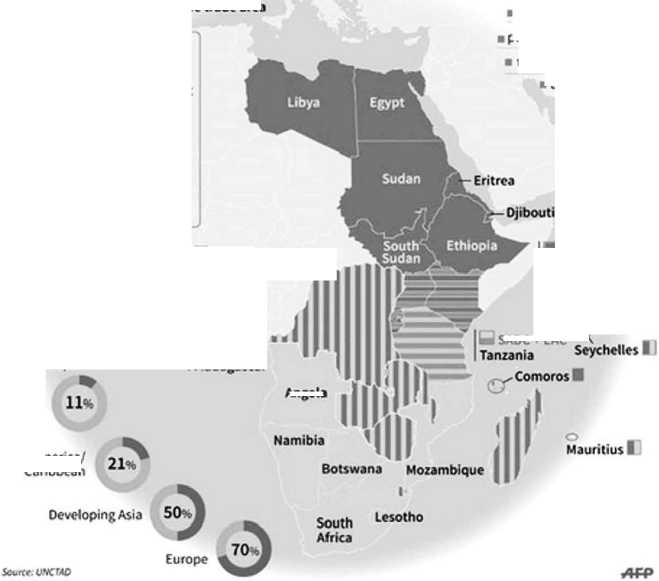

Even if Nigeria is not the member of this Agreement, it is important to mention the creation of a free trade area from Cape Town to Cairo in June 2015, which is possibly the most significant event in Africa since the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963. It is a grand move to merge existing principal regional organisations into a single African Economic Community. The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA)

includes 26 countries that are members of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), East African Community (EAC), and Southern African Community (SADC). The TFTA covers a population of 632 million and a combined GDP of USD 1.3 trillion. The area spans 17.3 million square kilometers, which is nearly twice the size of China or the United States (fig. 2).

Critics argue a single trading bloc will not work where individual sub-regional ones have failed. On the contrary, consolidation of three trading blocs will be founded on previous trade gains. Between 2004 and 2014, trade within the COMESA region grew from USD 8 billion to USD 22 billion, respectively. Over the same period, trade within SADC grew from USD 20 billion to USD 72 billion, and for the EAC from USD 2.6 to USD 8.6 billion. The total trade between the three areas rose from USD 30.6 billion in 2004 to USD 102.6 billion in 2014. Despite the growth, only about 12 % of Africa’s trade is intra-regional, while it is 22 % for South America, 40 % for North America, 50 % for Asia, and 70 % for Western Europe. Tariff liberation of 60-85 % will have a significant impact on the cross-border flow of goods and services. The TFTA will bring benefits to Africa in at least six mutually reinforcing ways.

■ EAC

Africa

East African Community

Intra-regional trade as a share of the region’s total exports (2007-2011)

A common market spanning half of Africa

A step towards a continental free trade area

Я COMESA* EAC Uganda Kenya Rwanda Burundi

• countries 26

population 625 million total GOP $1 trillion

■ aim boost trade between African countries

Tripartite Free Trade Area

Links 3 regional blocs

■ COMESA Common Market of East and Southern Africa

SA ОС South African Development Community

Angola

Fig. 2. Map of the TFTA

E COMESA * SAOC D. R. Congo Zambia Malawi Zimbabwe Swaziland Madagascar

SADC ♦ EAC 3

Latin America/ Caribbean

Note. Source: [2] on the basis of UNCTAD.

First, the conclusion of the Agreement will generate an impetus for the creation of similar arrangements in Western Africa, bringing economic powerhouses such as Nigeria into a continental free trade area. In addition, it is a bigger market, which free flow of goods and services will help to maintain economic growth at 6-7 % per year. At this rate, the combined GDP of Africa is projected to reach USD 29 trillion by 2050, which would be equal to the current combined GDP of the EU and the US.

With additional policies, such growth will contribute significantly to spreading prosperity and reducing poverty. The TFTA will serve as an impetus for investment in Africa’s cross-border infrastructure. It is estimated that Africa needs to invest nearly USD 100 billion annually in infrastructure over the next decade. By now, less than half of this target is met. One of the reasons for the low level of investment has been poor coordination across the different trading blocs. Building infrastructure will also create additional jobs and foster development of engineering services. Prospects for the larger markets and supporting infrastructure will spur industrial development. It both will create jobs and have an added advantage of diversifying Africa’s economies, which are now largely dependent on raw materials. The associated technological development will lead to the creation of new industries. Trade among the three blocs over the last decade has been dominated by intermediate products and manufactured goods, contrary to the common belief that African countries trade in similar agricultural products.

There are critical lessons for future negotiations. First is political will. This was demonstrated by the decision of presidents to approve a work program, create a roadmap for negotiations, and stick to the timetable. The second lesson is the importance of continuous learning process and experimentation. The three trading blocs served as laboratories that generated lessons for technical negotiations. The importance of incremental learning has prompted COMESA to establish a school of regional integration that started its operations in 2015. The school serves as a platform for sharing lessons learned through integration.

The TFTA is a key landmark in Africa’s economic history. It ranks in significance with the independence of Ghana in 1957, the creation of the Organisation for African Unity in 1963, and its reinvention as the African Union in 2002. To paraphrase Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, the best way to learn to be a continental free trade area is to be a continental free trade area [24]. During recent years, there has been much talk of the potential benefits of creating an integrated African commercial bloc; the TFTA may be seen as the first tangible sign of action being taken. Following signature of the TFTA, negotiations to broaden its territorial ambit to West African nations opened on June 15, 2015 at the African Union summit in Johannesburg. According to the AU, the ultimate aim is to establish an intra-continental market benefiting from a youthful, fast-growing population of about 1 billion and a combined GDP of USD 3 trillion [7].

The TFTA includes a number of key African economies, such as South Africa, Egypt, Angola, and Kenya. Indeed, the nations constituting the bloc account for approximately 60 % of Africa’s economic output. The creation of the TFTA may serve to simplify Africa’s complex overlapping trade zones, which in turn, will assist in attracting investors to the region. The TFTA does not currently include key West African economies, most notably, Nigeria. Although, negotiations on extension of the TFTA area are underway. Estimated timeline for the conclusion of such negotiations has been set at two years. The prospect of obtaining a positive result is highly dependent on negotiators having learnt valuable lessons from the seven-year period of negotiations, which culminated in the recent signature of the TFTA. The conclusion of such an agreement requires strong political will from the nations concerned in order to fuel progress and manage the process, for example, by way of approving a work program, creating a roadmap for negotiations, sticking to a clear and achievable timetable and utilising technical groups. The tariff-focused nature of the TFTA has also come under scrutiny. It is widely recognised that there is a vital need for the improvement of regional infrastructure in Africa if intra-continental trade is to increase. Although, as mentioned above, it is argued that the TFTA may trigger investment in infrastructure. Others argue that for intra-regional trade to be strengthened, infrastructure development must be addressed as a priority, before any removal of tariff barriers. The potential positive effects of the TFTA may be stifled in reality by the continuing existence of infrastructure-related barriers to trade.

Major effects of trade agreements on food production and security in West-Africa

A study carried out [6] where the impact of trade agreements between the EU and some selected West African countries (Nigeria inclusive) was analysed, revealed that food production and income generated therein were threatened by trade liberalization as local producers cannot cope with the lower prices of food products occasioned by mass importation from trade partners from such trade partners. Most of the agricultural products consumed by African countries are imported and this goes a long way in determining the production strength and subsequent revenue of indigenous producers, hence, food safety.

Interestingly, the European Union is West Africa’s biggest trading partner. It accounted for 30 % of the region’s exports and 40 % of its imports between 2002 and 2004 (Comtrade, 2006). The major exports include minerals (Crude Oil 43T%, Iron 3 %, Aluminum 2 % and Gold 1 %), agricultural products (cocoa 19 %, fresh fruit 3 %), fishery products (5 %) and forest products (timber 2 %, rubber 2 %). The share of agricultural and processed food products was 18 % of total West African imports from the EU of which dairy and milk products contribute the largest percentage of agricultural and processed food products (17 %), and closely followed by preparation of cereals, tobacco, fish and preparations of vegetables, fruits. However, it is worthy to point out that West Africa only commands less than 0.5 % of total EU exports [9].

Milk and dairy products contribute the largest share of West African agricultural imports from the EU (17 %). Over the last decade, the import of milk and dairy products has increased significantly [20]. The trade effects of partnership agreements for milk have varying peculiarities across the various West African countries. Ghana provides the biggest significant effect with a 24 % increase in milk imports from the EU with only marginal increase in Guinea and 9.5 % increase experienced in the region in general [36].

Poultry exports to West Africa from the EU have experience significant increase in the 1990s, but decreased towards the early 2000s [20]. Apart from Guinea, most of the West African countries in 2004 imported at least 12 % more from the EU than before the preferential trade agreement with Ghana’s import increasing by 32 %. Moreover, total trade diversion is 21 % of non-EU imports, which is highly significant. Imported poultry products are less expensive compared to those produced by domestically. This factor cannot be unconnected to the high cost of production connected with production inputs. This pose a threat to the indigenous farmers who in most cases are not given enough incentive to compete with international providers. This stifles local economy and exposes them to unfavourable conditions. This also reduces enterprise and ingenuity which is a big problem for self-sufficiency in not only African countries but developing countries who rely heavily on imported food products which has implications for employment, for production for the domestic and regional market and for food security. Furthermore, poultry industry in Ghana obtains feed component from grains through local grain producers, who supply poultry feed to the agricultural industry. These producers are also at a risk in terms of their production supplies if most of these grains are also imported. Increased grain supplies from trade agreements will definitely reduce the price of local producers thereby lowering their income and put their continuous operation on the edge. Hence, these agreements have a ripple effect on the entire food and agriculture sector of the countries with Nigeria not being an exception.

Trade in wheat and wheat flour has increased steadily over the last ten years. However, recently the export value of EU products has declined [20]. The effect of trade agreements has seen these products’ importation increase by 12.5 % in West Africa [36]. He further explained that Ghana experienced the largest shift in their import structure, where EU exports increased by 36.5 %, whereas Mauritania recorded 3.5 % with the EU-African Caribbean Pacific Agreement. However, this led to countries like Benin and Niger diverting 18 % and 16.5 % of their previously non-EU imports to the EU respectively. The result of this is that grain producers will have to compete with cheap, subsidized EU imported grains whose destination in most cases are the markets in the urban. With more negotiations on reduced tariff getting successful, it is more definite that imports to the countries will increase and become even cheaper, a serious concern for local producers. This is a situation that has really set the Nigerian agricultural sector aback as regards producing enough grains for production and consumption. In response to this, the government once banned the importation of rice and in some cases increased tariff to boost local production. But given the current economic realities in the country and increase in population which is related to food demand, one will still have to see how long it will last. This however is key to trigger the development of local economy.

Though there was a significant drop in EU exports to West Africa in 2004, nevertheless processed tomato products from the EU have increasingly entered the regional market and Nigeria experienced about 25.5 % increase in imports due to EU trade agreements [20]. In Nigeria, the challenge of Tomato processing industries is that most cannot compete with mass production from importation due to high cost of production occasioned by poor infrastructural facilities and lack of economies of scale [45].

Solutions and Recommendations

Based on the abovementioned, it can be stated that the international trade agreements for Nigeria have been important rather from diplomatic point of view so far. Because of corruption and political interest, they have not been able to contribute to the economic wellbeing of the entire society. From a sectoral point of view, Nigeria’s economy is still not balanced. There are dominant sectors, like oil for export purposes, but other sectors, such as agriculture, food industry, and services have not experienced significant development in the past few decades. Empirical evidence from an analysis [21] shows that agricultural export can be as lucrative and profitable as any of the other sectors in Nigeria with respect to returns on investment. Since recent shock in oil prices could render Nigeria in economic shambles, much attention is needed in the agricultural sector to overcome such subsequent challenges. In Nigeria, agriculture is an example of one key sector which role is and would remain crucial to development fortunes [33]. Economic history is replete with ample evidence that agricultural revolution is a fundamental pre-condition for economic growth, especially in developing countries [16; 34; 47].

It can be stated that the solution for the expected development would be the elaboration of an integrated, multi-sectoral development policy, considering the availability of resources, labour force, and capital. The regions of Nigeria should contribute to the national economic development and the development of the society according to their endogenous resources and potentials. The economic co-operation among regions and state should be encouraged [14]. In long-terms, the one-focused export should be expanded by alterative products, which requires development of some economic sectors. Import of food and agricultural product should be moderated by domestic production, which requires the use of abandoned lands and technological development of the sector. The role of international trade agreements should be to provide benefits for all the stakeholders – not exclusively in material terms, but they should create possibilities for participation for as many people as they can. People should use the benefits of such agreements as much as possible. Thus, the benefits of international trade agreements should have impact on the everyday life of people.

Future Research Directions

Based on the information available, we should state that even if Nigeria and the countries of Africa have had international trade agreements for long, they could not result in significant improvement in the standard of living, in food security, or safety. In order to see the real impacts of trade agreements, the improvement in the global and national macroindicators could be observed, despite of the fact that they have not had spectacular positive impact on the society and the economy as a whole yet. There are specific sectors which have played increasingly important role in the export and import relations, but agriculture still has unexploited capacities. Because of the increasing population, food production, food processing and securing safe food should be the core areas of future researches, with special focus on the trends of food imports and their relation to the food safety and security especially in the rural areas. It would be important to analyze how domestic agricultural and food production could be developed and how the unexploited capacities could be used to secure food and reduce the food-import dependence. Authors believe that the TFTA could provide good basis for a more diversified development for Nigeria – after the decision on accession is made. Regarding the EU-Nigeria relations, more researches could be carried out on the experience with member states to define the basis for mutually beneficial fields of cooperation and to define the steps to be made to have more balanced trade relations – which is not the situation at this moment.

Conclusion

Nigeria is expected to be on track to becoming one of the twenty largest economies in the world by 2020, therefore structural reforms in the economy and society, including international trade are inevitable. Despite the fact that since 2008 the government has begun to implement the market-oriented reforms urged by the IMF, such as modernisation of the banking system, removal of subsidies, resolving of regional disputes over the distribution of earnings from the oil industry, and development of stronger public-private partnerships for roads, agriculture, and power, the improvement is not equalized.

The importance of trade and agreements between countries and/or organisations cannot be overemphasised, because no country can stay totally independent of the others. However, developed countries must see less-developed ones as trade partners and not ones in need of aid or relief due to the impoverishment. Most countries in Africa have not come close to getting the best out of their trade agreements. The best they get is trade barrier reduction. In most cases, domestic goods cannot compete with the foreign ones that come in the reverse due to low capacity and technical deficiencies. Going forward, Nigeria and other countries of same status must painstakingly look inwards to harness the untapped resources within (country and region), build capacity, and ensure political and economic stability, so that the local industries can benefit mutually and comprehensively from the gains occasioned by such agreements. Nigeria as a matter of necessity, must go beyond trade agreements hinged primarily on oil and gas, but focus more on diversification and service sector especially in the face of dwindling oil prices.

Nigerian economy needs growth in order to reduce financial burden of imports, create jobs to absorb the growing unemployment, increase incomes, reduce poverty, and increase prosperity. Social development is vitally important for a country, which is the most populous in Africa, and where harmony and peaceful co-existence among various religions and ethnic communities is really fragile. Creating more jobs in rural areas may diminish tensions and popularity of radical political groups, especially among young generations. Application of new technologies and methods may rapidly increase the efficiency of agricultural production. Those lands which have been abandoned due to the scarcity of water could be still kept in cultivation.

After all, agricultural reforms should serve not only the development of the rural society, but indirectly be a valuable contribution to peace and security of the West-African region.

According to the authors’ judgement, multilateral agreements on economic co-operations have not yet contributed to the economic development of Nigeria in a significant extent. Even though in terms of GDP, the economy grew, but the real development, which would bring about the metamorphosis of the Nigerian economic structure still has not come about. From many aspects, ECOWAS members are competitors to each other rather than promising partners for future co-operation. In terms of trade, ECOWAS and other intra-African regional agreements are not success stories, however it has a distinct and positive role in political dimensions.

The same can be claimed about the laboured EPA agreements. The EU countries still have been following their own economic interests in the African region, and as a rule, the former colonizers have incomparable advantages. Not surprising that the overwhelming weight of the European-Nigerian trade and investment is represented by the United Kingdom, France, and other West European countries, while the new members – including Hungary – have lower trade volumes. In 2012, Spain was the 5th, the Netherlands was the 6th, while Portugal was the 8th in the top-10 fastest growing exporters to Nigeria. The fact that Nigeria’s imports from the UK rose by 99.17 % in 2012 also shows its strong trade relations with this country. Even if there is no free trade agreement with the UK, it is one of the largest investors in Nigeria. In 2011, the UK and Nigeria agreed on a joint mandate in a pursuit to double trade from £4 billion to £8 billion by 2014. The target has almost been achieved, with a bilateral trade of £7.2 billion in 2012. Regarding France, in 2014, export to France from Nigeria was USD 5.8 billion, while in 2011 it reached USD 7.4 billion. On the case of Nigeria and many other African countries, it looks that bilateral co-operation works much better than multilateral. At least the intensive and successful economic expansion of China in Africa seems to justify it.

In a nutshell, when we look at the implications of trade agreements between Nigeria and international bodies, trade organisations and other countries, it is clear that since the country is a net importer of agricultural products, the local industry will have no other option than face serious competition from international producers. One of such challenges is a resultant decrease in prices for some of their products thereby reducing their incentives to produce for the market. This is worrisome as about 70 % of Nigerians are into agriculture, hence their source of income and employment is threatened. And of these, the majority are in the rural area. And the rural area being already bedeviled by high poverty rate and poor infrastructure, food insecurity is greatly threatened especially when we consider the perpetually growing population of the country. Not only will the smallholders be affected, but also industries. However, this effect will not be felt more in the Urban areas because they will benefit from the lower prices as they are basically consumption driven (net-consumers). Therefore, there is not just a political angle to trade effects on food production and security, but also a socio-economic angle as well. It is important as a matter of necessity and urgency to monitor the sensitivity and consequences of this process on the local markets, households and economy as a whole.

Список литературы The role of international trade agreements in the economy of developing countries (the case of Nigeria)

- Adesina A. Agricultural Transformation Agenda: Repositioning Agriculture to Drive Nigeria’s Economy. Abuja: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2012. URL: https://queenscompany.weebly.com/uploads/3/8/2/5/38251671/agric_nigeria.pdf.

- Africa leaders sign ‘Cape to Cairo’ free trade bloc deal. URL: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3117792/African-leaders-unveil-new-commonmarket-bloc.html.

- African Countries Trade Agreements (n.d.). In Focus Africa. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://focusafrica.gov.in/Trade_Agreements_Africa.html.

- African Economic Outlook. (n.d.).African Economic Outlook -Nigeria 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fileadmin/uploads/aeo/2013/PDF/Nigeria%20-%20African%20Economic%20Outlook.pdf.

- Amadou S. Will There Be an African Economic Community? Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/hearing-on-will-therebe-an-african-economic-community.

- Busse M., Großmann H. Assessing the Impact of ACP/EU Economic Partnership Agreements on West African Countries, HWWA Discussion Paper 294. Hamburg, Hamburg Institute of International Economics, 2004. URL: http://hubrural.org/IMG/pdf/hwwa_impact_ape_on_ecowas_eng.pdf.

- Cannon A., Major R. Signature of the Tripartite Free Trade Agreement (TFTA) on 10 June 2015: The First Step Towards a United African Free Trade Bloc? Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: http://hsfnotes.com/publicinternationallaw/2015/07/07/signature-of-thetripartite-free-trade-agreement-tfta-on-10-june-2015-thefirst-step-towards-a-united-african-free-trade-bloc/.

- Central Bank of Nigeria. Annual Report and Financial Statement for the Year Ended 31 December 2009. Abujaá Central Bank of Nigeria, 2010. URL: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/OUT/2010/PUBLICATIONS/REPORTS/RSD/Link%20Files/PART%20TWO.pdf.

- Comtrade. Website. URL: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/comtrade/.

- Davies A.E. Food Security Initiatives in Nigeria: Prospects and Challenges, Monograph. Nigeria, Ilorin, Department of Political Science, University of Ilorin, 2009, pp. 25-30.

- Dieye C.T. What Is Africa Worth in the International Trading System? Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/bridges-africa/news/what-isafrica-worth-in-the-international-trading-system.

- Economic and Commercial Counsellor’s Office in Nigeria. Brief Introduction of Bilateral Relations.Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: http://nigeria2.mofcom.gov.cn/article/bilateralcooperation/inbrief/201407/20140700669579.shtml.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. Country Commerce Nigeria. New York, NY: Economist Intelligence Unit, 2010. URL: https://store.eiu.com/product/country-report/nigeria.

- Edoumiekumo S.G., Audu N.P. The Impact of Agriculture and Agro-based Industries on Economic Development in Nigeria: An Econometric Assessment. Journal of Research in National Development, 2009, no. 7 (1), pp. 1-8.

- Egunsola O. Should Nigeria Sign the Economic Partnership Agreement? Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://nigeriannet.com/should-nigeria-sign-theeconomic-partnership-agreement/.

- Eicher C., Witt L. Agriculture in Economic Development. New York, NY, McGraw Hill Publ., 1964, pp. 169-181.

- Emeka A. Experts debate proposed EUECOWAS partnership agreement. Tralac. Retrieved from 30 September 2016. URL: https://www.tralac.org/news/article/7793-experts-debate-proposed-eu-ecowaspartnership-agreement.html.

- Engelberth I. Változó kínai gazdasági és politikai jelenlét Afrikában (The Changing Chinese Economic and Political Presence in Africa). In K. Solt (Ed.), Alkalmazott tudományok II. Fóruma. Budapest, Budapest Business School Publ., 2015, pp. 121-145.

- European Commission. (n.d.). ACP -The Cotonou Agreement. Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/regions/african-caribbeanand-pacific-acp-region/cotonou-agreement_en.

- Eurostat. Website. URL: http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int/portal/page?_pageid=1090,30070682,1090_33076576&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL,Retrieved January 5, 2006.

- Ijirshar V.U. The Empirical Analysis of Agricultural Exports and Economic Growth in Nigeria. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 2015, no. 7 (3), pp. 113-122.

- Ikoku E.U. Self-reliance: African Survival. Enugu, Nigeria: Fourth Dimension Publishers, 1980, pp. 41-46.

- International Cocoa Organization. SPS Capacity Building in Africa to Mitigate the Harmful Effect of Pesticides Residues in Cocoa and to Maintain Market Access. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://www.icco.org/projects/10-projects/193-sps-capacity-building-inafrica-to-mitigate-the-harmful-effects-of-pesticides%20residues-in-cocoa-and-to-maintain-market-access.html.

- Juma C., Mangeni F. The Benefits of Africa’s New Free Trade Area. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/publication/25444/benefits_of_africas_new_free_trade_area.html.

- Lavy V. Alleviating transitory food crisis in subSaharan Africa: international altruism and trade. World Bank Economic Review, 1992, no. 6, pp. 125-138.

- Mefor L. Senator Ken Nnamani Portrait and the New Nigerian Senate. Abuja, Psykom Publishing Ltd., 2007, pp. 13-15.

- National Planning Commission. Nigeria Vision 20:2020. Abuja, Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2009. URL: http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/nigeria/nigeria-vision-20-20-20.pdf.

- National Planning Commission. The Transformation Agenda -Summary of Federal Government’s Key. Priority Policies, Programmes and Projects 2011-2015. Abuja, Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2016, pp. 3-26.

- Neszmélyi G. The Issues of Sustainability and Self-sufficiency in the Nigerian Food Economy. In G. Neszmélyi (Ed.). Socio-economic and Regional Processes in the Developing Countries. Gödöllő, Szent István University Publ., 2014, pp. 98-116.

- Nigeria Map. URL: https://www.ezilon.com/maps/africa/nigeria-maps.html.

- Nigerian Export Promotion Council. Expanding Nigeria’s Exports of Sesame Seeds and Sheanut/Butter through Improved SPS Capacity Building for Private and Public Sector. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://www.aflasafe.com/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=9adeb84f-67c2-4de8-9082-110a27b94489&groupId=524500.

- Ojo O.E., Peter F. Adebayo. Food security in Nigeria: an overview. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 2012, no. 1, 2, pp.199-222.

- Olajide O.T., Akinlabi B.H., & Tijani A.A. Agriculture Resource and Economic Growth in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 2012, no. 22 (8), pp. 103-115.

- Oluwasanmi H.A. Agriculture and Nigeria’s Economic Development. Ibadan, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. 144-167.

- Orumgbe R. (n.d.). The Effect of World Trade Organisation on Nigeria Maritime Industry. Retrieved November 16, 2016. URL: http://www.academia.edu/11962449/the_effect_of_world_trade_organisation_on_nigeria_maritime_industry.

- Pannhausen Ch. Economic Partnership Agreements and Food Security: What is at stake for West Africa? Political Science and Development Economics at Bonn University. German Development Institute (DIE). URL: https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/Economic_Partnership_Agreements_and_Food_Security.pdf, Visited December 5, 2016.

- Perkins W.A. & Stembridge J.H. Nigeria -A Descriptive Geography (3rd ed.). Ibadan, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. 36-57.

- Pomfret R. The Economics of Regional Trading Arrangements. Oxford, Oxford University Press Publ., 2001. Retrieved November 3, 2016. URL: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/0199248877.001.0001/acprof-9780199248872.

- Ramonet I. Africa Says No -And Means It. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: https://mondediplo.com/2008/01/01africa.

- Tarrósy I. Politikai elméletek és módszertanok a mai afrikai problémák megértéséhez. In S. Csizmadia & I. Tarrósy (Eds.), Afrika Ma -Tradíció, átalakulás, fejlődés. Pecs, IDResearch Kft. & Publikon Kiadó, 2009, pp. 13-17.

- Tarrósy I. Nigéria választ -Újrázik-e Goodluck Jonathan? (Nigeria will Elect -Will Goodluck Jonathan Come Again). Afrika Tanulmányok, 2014, no. 4, pp. 5-12.

- Taylor I. Africa Rising? BRICS -Diversifying Dependency. Oxford, James Currey, 2014. 194 p.

- The Observatory of Economic Complexity, Retrieved October 11 2016. URL: http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/nga/.

- United Nations Commission on Trade and Development. (2013). Nigeria Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). Retrieved November 17, 2016. URL: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA/CountryBits/153#iiaInnerMenu.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. The Least Developed Countries Report. Geneva, United Nations, 2002. URL: http://unctad.org/en/docs/ldc2002_en.pdf.

- US Department of State. U.S. Relations with Nigeria. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2836.htm.

- Woolf S.S., Jones E.I. Agrarian Change and Economic Development: The Historical Problem. London, Methuen Publ., 1969. 192 p.

- World Trade Organisation. Council for Trade in Services -Special Session -Nigeria -Initial Offer -Document TN/S/O/NGA. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/docs_e.htm.

- World Trade Organisation. Committee on Trade and Development -Sixteenth Session on Aid for Trade -Nigeria’s Trade and Productive Capacity Reform -Document WT/COMTD/AFT/W/23. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/docs_e.htm.

- World Trade Organisation. Trade Policy Review Body -Trade Policy Review -Report by the Secretariat -Nigeria -Document for Nigeria WT/TPR/S/247/Rev.1. Retrieved November 18, 2016. URL: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/docs_e.htm.

- Zsarnóczai J.S., Lakner Z., Mughram Y.A. Hungarian Participation in Modernisation of the Third World. In I. Szűcs & Zsarnóczai J.S. (Eds.). Economics of Sustainable Agriculture. Gödöllő, Szent István University Publ., 2011, pp. 87-108.