The topography of ritual buildings in villages of the Tobolsk governorate (late 19th to early 20th century)

Автор: Mainicheva A.Y.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145453

IDR: 145145453 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4.112-119

Текст обзорной статьи The topography of ritual buildings in villages of the Tobolsk governorate (late 19th to early 20th century)

Ritual buildings are symbolic in any culture, embodying people’s religious beliefs and worldview. The study of the way religious structures are placed helps us to understand the symbolic and topographic role of religious buildings in the collective consciousness of society. The attention of scholars should thus be directed toward the topography of churches, chapels, mosques, etc., understood in this case as semantic features of the location of buildings and structures. One of the methods for exploring these features is the analysis of the urban situation, as it was done, for example, by A.A. Prokudina and M.S. Tomskaya (2009). When studying the symbolic aspects of ritual buildings’ placement, it is advisable to supplement research using the case-study method, applied to the analysis of reference data and site plans. In addition, when we speak about the symbolism of Orthodox ecclesiastical architecture, it is impossible to ignore hagiographic writings and religious attitudes. This fosters the need to address theological literature, doctrine, and canons. The important role of this approach is preconditioned by the specific nature of symbols in Orthodoxy, which are understood not simply as conventional images or signs. According to the Church doctrine, ecclesiastical symbols embody the heavenly or divine prototype and thereby they fulfill their purpose.

This study is the first attempt to identify the specific features of ritual buildings’ placement in the settlements of the late 19th to early 20th century using evidence from the “Reference Book of the Tobolsk Diocese by September 1, 1913” (hereafter, RBTD) (Spravochnaya kniga…, 1913) and site plans of the villages of the

Tobolsk Governorate drawn in the 1840–1880s on the order of the Tobolsk Treasury Chamber in connection with measures to regulate settlement development and allocate land plots for the settlers, from the State Archives of Tobolsk (GBUTO “City archive in Tobolsk”, F. 154, Inv. 2). The scholarly value of these sources has been analyzed; their reliability and rich information content have been established (Kurilov, Mainicheva, 2008). Notably, these reference materials contain data only on Christian churches and chapels. This study will not consider popular understanding of images and symbols of Orthodoxy, since the sources employed do not make it possible to take into account its specific features. Decisions on the placement of buildings and other architectural structures, and consecration of altars were made at the official level by civil and religious authorities in accordance with rules and doctrines. Our hypothesis is that the features of topography of the semantically important religious buildings could be manifested in the clearest manner in the settlements with complex ethnic composition and non-Russian population. Therefore, from more than 15 site plans, which stipulated the placement of a church or chapel, we focused on those that were drawn for the settlements located in the districts with mixed population (Russians and native non-Russian minorities, according to the terminology that existed in the documents of the Russian Empire in the late 19th to early 20th centuries; the names of ethnic groups will be given in accordance with this terminology), where ritual buildings were available. There were three such settlements: the village of Obdorskoye in Berezov Okrug, as well as the village of Romanovskoye with the Romanovskie yurts and the Kobyatskie yurts in the Tobolsk Okrug of the Tobolsk Governorate. In the list of settlements for 1868– 1869, compiled at a time close to the period when the site plans were created, there were 11 Russian villages, 144 non-Russian uluses, and no non-Russian yurts in Berezov Okrug; and 36 Russian villages, 194 non-Russian yurts, and no non-Russian uluses in Tobolsk Okrug (Spiski naselennykh mest… (the List of Settlements, hereafter, SNM), 1871). Unfortunately, there was no information on the ratio of the ethnic groups in the population of each of the settlements, but the site plans clearly indicated the areas where both Russians and native non-Russian minorities resided. The SNM mentioned the districts where native non-Russian minorities lived (Ibid.: CLIII): the Samoyedic people and Ostyaks roamed near the village of Obdorskoye in Berezov Okrug and wintered on a part of the village territory; the Tatars lived in the yurts of Tobolsk Okrug (Ibid.: CLIV, CLVIII); and the Kobyatskie yurts were mentioned as a Tatar settlement (Ibid.: CLIV). The compilers of that reference book noted that the non-Russian population prevailed over the Russian population in Berezov Okrug: 100 people of both sexes included 21 Samoyedic people and 63 Ostyaks

(Ibid.: CLIX), while Tobolsk Okrug could be considered “the center of the Tatar population” (Ibid.: CLIV), since there were 25 Tatars per 100 Russians.

One of the problems of the site plans under consideration is the lack of contour lines, which complicates the analysis of the landscape and does not make it possible to establish the height of the area where a ritual building was located in relation to other buildings. However, it is still possible to imagine the general altitudinal position of the settlement area, since the direction of the river flow was indicated, and it is known that the right bank of rivers in Western Siberia is steeper than the left bank. For example, an elevated sand-clay mountain (or hill) stretched along the right bank of the Ob River, which rose five sazhens above the waterline in the area of the village of Obdorskoye (Ibid.: X).

Specific features of ritual buildings’ placement in the settlements

A drawing of the site plan completed in 1846 for the settlement of Obdorskoye (present-day Salekhard) in Berezov Okrug (Fig. 1) was found in the archive of the Tobolsk Governorate. The plan was made by the Turinsky junior land surveyor Devyatov dated December 9–12, 1846, on the order of the Tobolsk State Chamber from December 2, 1846. The village of Obdorskoye was located on the Pilui River (present-day Polui River), a tributary of the Ob River. The site plan was drawn schematically, and only individual zones are visible. The network of streets is not shown. The building system was located along the SW-NE line; from south to north it was cut by a ravine and stream valley. The southwestern part was occupied by residential buildings; the northeastern part was occupied by trading shops which were located on an area of 40 × 170 sazhens adjacent to the territory of the new (as noted on the site plan) Orthodox cemetery with an area of 20 × 70 sazhens. The outskirts of the southwestern part of the village were occupied by the church with an area within the fence measuring 10 × 20 sazhens. A stone church with stone bell tower was built in 1886– 1894 at the expense of the parishioners and the merchant A.M. Sibiryakov. There were three altars in the church: in the name of Apostles Peter and Paul, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, and St. Basil the Great (Spravochnaya kniga…, 1913: 36). The altars were oriented to the east. This irregularly shaped area free of development measured 40 × 50 sazhens (40 oriented toward the northsouth and 50 toward the east-west) and was located on the high bank of the stream. The church was built on the place of the ancient pagan shrine (Ieromonakh Irinarkh, 1906: 17). The old Orthodox cemetery, which was closed according to the plan for settlement arrangement from October 27, 1830, was located near the church. The house of the clerk Karpov with barns, non-Russian log house for collecting tribute, as well as non-Russian log cabins for wintering, were on the other side of the stream.

The site plan for the village of Romanovskoye with the Romanovskie yurts, that is, the places where the Tatars of the Demyanskaya Volost of the Tobolsk Governorate lived, was compiled by the Junior District Land Surveyor Mokrinsky of Tara in 1878 on the order of the Tobolsk Treasury Chamber from September 3–5, 1877, and approved on June 23, 1879 (Fig. 2). The village consisted of one curved street of a single row of buildings, and was located along the left bank of the Chanbyshevaya River, which flowed almost parallel to the Irtysh River and fell into it along the SW-NE line. An area of 33

households was drawn on the site plan. The housing area was limited by the rivers to the southeast and by the Bezymyannoye swamp to the northwest, and had a wooden one-story church built in 1831 in the center. The church had two altars: in the name of the Apostles Peter and Paul, and Archangel Michael. The altars were oriented to the northeast. The reference book mentions a chapel (Spravochnaya kniga…, 1913: 22), but it was not marked on the plan; it might have been built after the site plan was completed. The priest’s house and rural school with their land plots were located not far from the church, closer to the river bank; these structures were divided by a lane, which led to the river. In order to secure the access of the church’s territory to the river, it was planned to demolish dilapidated non-residential buildings. Yurts were located to the northeast of the rest of the building area, on the border with the irregularly shaped church plot measuring 20 × 60 sazhens. A cemetery directly adjoined the yurts in the northeastern part of the settlement.

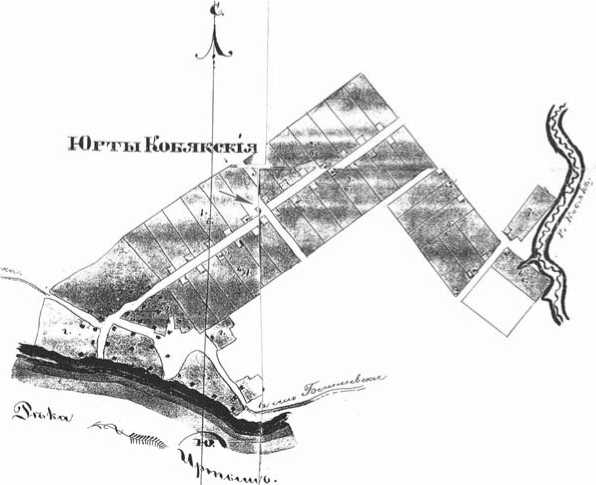

The Kobyatskie yurts in Begishevskaya Volost of Tobolsk Okrug, Tobolsk Governorate, was a settlement where the Tatars lived. Its site plan (Fig. 3) was made for native non-Russian minorities of the Vagaiskaya non-Russian Volost by the land surveyor Mokrinsky on October 3, 1877, upon an order of 1877, and was approved on November 2, 1877. The yurts with 34 land plots were located on the right bank of the Irtysh River. A residential system of the

ь МАСШШАВЬ *ик«8 р*«ь1иь 1Л<^ /tge^W'K

Л^ юанЗДс (10

1 «ЛМ V5HU1

-

Fig. 1 . Fragment of the site plan showing the village of Obdorskoye, 1846 (GBUTO “City archive in Tobolsk”. F. 154, Inv. 21, D. 98, fol. 1).

1 – church of Apostles Peter and Paul; 2 – old Orthodox cemetery; 3 – new Orthodox cemetery; 4 – steppe of the nomadic Obdorskoye native non-Russian minorities.

-

Fig. 2 . Fragment of the site plan showing the village of Romanovskoye with the Romanovskie yurts, 1878 (GBUTO “City archive in Tobolsk”. F. 154, Inv. 21, D. 963, fol. 1).

1 – church; 2 – cemetery; 3 – Bezymyannoye swamp.

“nested” type was converted into a street system with two-sided placement of land plots. One long main street going towards the northeast from the bank of the river was planned; it was crossed by two small streets: one in the center of residential quarters, and the second at the northern end of the yurts, which had access to the Kobyak River. One old street was located along the bank and was a part of the road from the city of Tobolsk to the village of Golyshevskoye. According to the site plan, all structures on both sides of the road were to be demolished in order to free the collapsing bank of the Irtysh River. A mosque with a fence on a plot measuring 10 × 15 sazhens was to be placed at the center of the new main street, a small distance from the intersection. Its entire land plot was equal in area to an ordinary household plot. It is difficult to establish exactly how the mosque was supposed to be built, but according to the tradition, it had to have been strictly oriented toward the Kaaba in Mecca.

Fig. 3 . Fragment of the site plan showing the Kobyatskie yurts, 1877 (GBUTO “City archive in Tobolsk”. F. 154, Inv. 21, D. 3768, fol. 1). An arrow indicates the place where the mosque was built.

In the villages of Obdorskoye and Romanovskoye with yurts there were Orthodox churches, and in the Kobyatskie yurts a mosque, which reflected the religious and cultural situation in the region. In SNM, the Samoyedic people were called idol-worshippers. Christianization met their active resistance. The Samoyedic people even murdered the baptized Ostyaks (Spiski naselennykh mest…, 1871: CLXII). There were churches intended not only for spiritual guidance of the Russian population living there, but also for fostering the conversion of pagans to Orthodoxy in the settlements, near which the Samoyedic people roamed. The Tatars followed Sunni Islam, and their conversion to Orthodoxy was an exception (Ibid.: CLVI). They were subordinate to the Orenburg Spiritual Mohammedan Assembly; for their worship in the yurts a mosque was built.

Dedication of church altars

Dedication of altars in churches is important for our discussion. In the villages of Obdorskoye and Romanovskoye, the main altars were dedicated to the Apostles Peter and Paul (feast day July 12, or June 29 according to the Julian Calendar)—zealous propagators of Christianity among the Gentiles and Jews, as follows from the Lives of these saints. According to the Church doctrine, the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles on the day of Pentecost; they received the gift of testifying about the Lord before the nations in order to spread the message of divine miracles in various languages. The

Acts of the Apostles mention that the Apostles Peter and Paul preached repentance and converted many Jews and Gentiles to Christianity (Acts 13: 46). It is thus sung in their Magnification hymn: “We magnify you, Apostles of Christ Peter and Paul, who have enlightened the whole world by your teachings and have brought all the ends to Christ”. Already the early Christians venerated the Holy Apostles. Their veneration began after their martyrdom, and their burial place became a Christian holy place. In the Russian Orthodox Church, the feast day of these saints has acquired the status of one of the 18 great feasts, including Easter, the twelve Great Feasts, the Protection of the Holy Mother of God, Circumcision of the Lord, Nativity of John the Baptist, and Beheading of John the Baptist. Images of the Apostles Peter and Paul in the iconostases of the Orthodox churches have become a canonic part of the Deesis.

According to the Church tradition, people pray to the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul for their help in Godpleasing undertakings, bringing non-Christians to the Christian faith, and strengthening in faith those who have lost it. The Orthodox Church glorifies the Apostles who worked hard to spread Christianity, praises the firmness of Peter and reason of Paul, and regards them as an image of the conversion of sinners and those who are being corrected. The dualism of the images of Apostles Peter and Paul as a symbol of a difficult path to the faith was reflected in their lives: Apostle Peter was with Christ from the very beginning, denied him, but repented, while Apostle Paul was a staunch opponent of the Savior, but converted and became his firm follower (see (Protoierey

Aleksandr Men, (s.a.))). It is clear that in the complex ethnic and religious situation in Siberia in the 19th to early 20th centuries, the images of the Apostles played an important symbolic role, which was intended to invigorate the spirit of believers and bring the doctrines of Orthodoxy into a non-Russian environment.

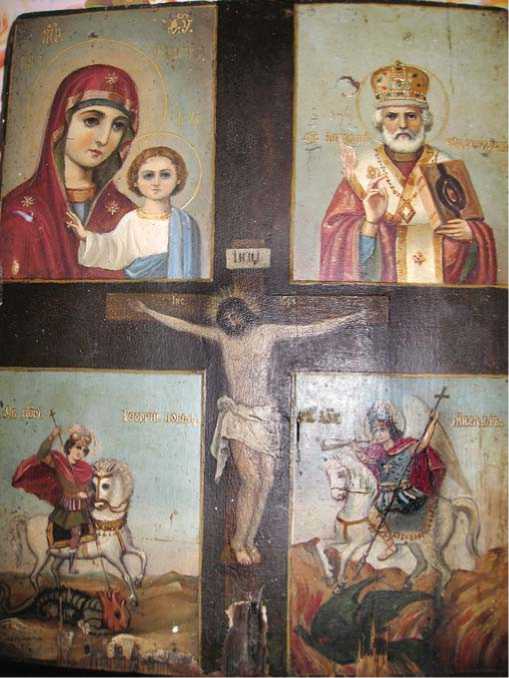

The altar of the Obdorskoye church is dedicated to another symbolic image of Orthodoxy—St. Nicholas the Wonderworker (feast days December 19, or December 6 according to the Julian Calendar; May 22, or May 9 according to the Julian Calendar; and August 11, or July 29 according to the Julian Calendar), as well as weekly commemoration on every Thursday. Cultural, philological, and ethnographic studies (see, e.g., (Vinogradov, 1900; Mainicheva, 2005a, 2006; Ryndina, 2002, 2005; Sarbash, (s.a.); Sidorenko, 1993; Uspensky, 1982; Fursova, 2001; Shaizhin, 1909; and others)) have established the great importance of St. Nicholas in Russian culture as a patron saint of travelers and seafarers, as well as a defender, helper, and protector of people. In the iconography, the sword in the hands of St. Nicholas (a holy warrior who defended an Orthodox city from foreigners) was interpreted as the armament of a warrior and as “the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God” (Eph. 6:17), by which sins are destroyed (Fig. 4). The image of St. Nicholas was associated with protection from sin, as well as bodily and spiritual sorrows. In the “Menaion Reader”, it is succinctly said that St. Nicholas “performed many great and glorious miracles on the earth and on the sea, helping those in harm, and saving them from drowning, and bringing them to dry land from the depths of the sea, delivering them from corruption and bringing them home, delivering people from bonds and dungeons, protecting them from death by the sword, and freeing them from death, and granting many cures to many people… He has enrichened many of those who suffer from the utmost poverty and misery, has given food to the hungry, and is a ready helper, warm protector, and fast defender and intercessor to everyone in every need, and he helps those who call on him and delivers them from troubles” (Tserkovno-narodniy mesyatseslov…, 1990: 64). Obviously, the dedication of one of the altars of the church on the northern edge of the Russian Orthodox world to St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was more than appropriate.

The third altar of the Obdorskoye church was dedicated to Basil the Great—another revered saint of Orthodoxy (feast day January 13, or January 1 according to the Julian Calendar; the general commemoration of the Three Holy Hierarchs—St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, and St. John Chrysostom is on February 12, or January 30 according to the Julian Calendar) (Fig. 5). It follows from the Life of the saint that he possessed profound knowledge, was famous due to his endeavors for the benefit of the Orthodox world and unity, and supported the Christians, strengthening their faith and calling for courage and patience. St. Basil spent all his personal wealth on the poor: he created almshouses, homes for travelers, and hospitals, as well as male and female monasteries. His contemporary Bishop Amphilochius thus praised his merits: “He… has been able to help not only his fellow countrymen, but also all countries and towns of the world and all people, and he has always been and will be a most saving teacher for all Christians”

Fig. 4 . Hinged icon of St. Nicholas with a sword and model of a church. Metal. Vagaisky District, Tyumen Region, FMA, 2010.

Fig. 5 . Icon of the Three Hierarchs: St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. Basil the Great, and St. John Chrysostom. Metal. From the collection of the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve.

Fig. 6 . Icon with St. Nicholas and Archangel Michael on the right side. Vagaisky District, Tyumen Region, FMA, 2015.

(Svyatitel Vasiliy Velikiy, (s.a.)). In his “Homily on the Commemoration Day of His Brother, Basil the Great”, St. Gregory of Nyssa wrote: “…he again ignited… the teaching of faith… by the power of grace which dwelt in him. He appeared to the Church as a beacon for those wandering at night on the sea, he directed everyone to the true path…”, likening St. Basil the Great to other champions of Christianity, such as Apostle Paul, Elijah, and John the Baptist (Svyatitel Grigoriy Nisskiy, (s.a.)).

The second altar in the church of Apostles Peter and Paul in the village of Romanovskoye was dedicated to Archangel Michael (feast days September 19, or September 6 according to the Julian Calendar; and November 21, or November 8 according to the Julian Calendar). According to the Scriptures, Archangel Michael is one of the highest angels, leading an army of heavenly incorporeal powers inhabiting the spiritual world, through whom God can communicate his will to people. In the Scriptures, Archangel Michael acts as a fighter against the devil and against lawlessness among people. In the Book of Revelation, the Archangel Michael appears as the main leader in the war against the dragon-devil and other rebellious angels: “…And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan.” (Rev. 12, 7–9). Apostle Jude mentions Archangel Michael as the adversary of the devil (Jude, 9, cf. Joshua 5, 13–14; Dan. 10; 12, 1). Archangel Michael is credited with the defeat of the Assyrian army, besieging Jerusalem in the times of the Prophet Isaiah (2 Kings 19, 35). The Church reveres Archangel Michael as a defender of faith and fighter against heresies and any evil. In one of the popular iconographies, he is depicted with a fiery sword in his hand or a spear that overthrows the devil (Fig. 6).

Taking into account the above church symbols, which according to Orthodox doctrine possessed a special power and effectiveness, the name of the altars of churches in honor of Archangel Michael, the Apostles Peter and Paul, St. Basil the Great, whose images were associated with the idea of physical and spiritual protection of people, as well as the spread and affirmation of Christianity, and were believed to have belonged to the highest ranks of the “heavenly hierarchy” cannot be considered random. For instance, St. Theophan the Recluse wrote: “…Our Lady the Mother of God is… above everyone… She is followed by incorporeal ranks, nine, in their order; then follow the saints of God: the Prophets and the greatest Prophet John the Forerunner; Apostles with the preeminent Apostles Peter and Paul; Holy Bishops including those considered to be Great: Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, and John Chrysostom, St. Nicholas, as well as the Russian Holy Bishops Peter, Alexis, Jonah, and Philip; Martyrs, Confessors, Holy Monks, Holy Unmercenaries, and Fools for Christ” (Svyatitel Feofan Zatvornik, (s.a.)). Reference materials indicate the distribution of altar dedications for the churches under consideration in the Tobolsk Governorate by the early 20th century, mentioning 625 altars with 97 names, with the largest number of altars in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker (79). There were fewer altars of other dedications, including Archangel Michael (31), the Apostles Peter and Paul (25), and St. Basil the Great (4) (for more details see (Mainicheva, 2005b: 122; Kurilov, Lyutsidarskaya, Mainicheva, 2005: 75–90)). The dedications of the four altars in the churches in the two settlements with mixed population analyzed above were among the top ten in terms of prevalence in the Governorate.

Conclusions

Villages with mixed population in the Tobolsk Governorate had Orthodox churches and chapels, and villages with Tatar population had mosques. The stone church in the village of Obdorskoye and wooden church in the village of Romanovskoye with the Romanovskie yurts were located in an elevated place or in the center of residential development, and had free access to natural landscapes, following the traditions of Russian church-building. Information on specific reasons for dedicating altars in churches, for example, in memory of some historical event or specific person, which was often the case, has not been found; however, the common symbolic importance of altar dedication for the spiritual appropriation of the territory by the population with Orthodox identity is obvious. Revered cults, which were important for protection in a material and spiritual sense, affirmation of the values, canons, and doctrines of Orthodoxy, and strengthening the spirit, were chosen taking into consideration the ethnic, religious, and cultural situation. Dedication of altars to Archangel Michael, the Apostles Peter and Paul, St. Basil the Great, and St. Nicholas was intended to play an important role in the spiritual life of the population. According to the site plan, the mosque in the Kobyatskie yurts was supposed to be located along the street as a part of the row of buildings, standing out among the residential housing with its architecture, which corresponded to the Islamic tradition. The plans for the building of a Muslim architectural structure for prayer, which was of symbolic importance, testifies to the recognition of religious sentiments and needs of the followers of Islam in the society, and symbolically manifests the religious identity on the part of the inhabitants of the yurts. In the late 19th to early 20th century, the topography of symbolically important ritual buildings in the settlements of the Tobolsk Governorate with a population of different ethnic composition and religious beliefs, was associated with the existing strategy of religious guidance, religious symbolism, and ethnoreligious identity of the dwellers.

Acknowledgements