The Ussuriysk Tortoise-A 13th century Jurchen monument

Автор: Artemieva N.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Paleoenvironment, the stone age

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145466

IDR: 145145466 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4.099-104

Текст обзорной статьи The Ussuriysk Tortoise-A 13th century Jurchen monument

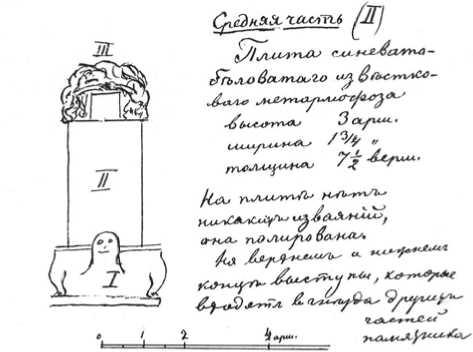

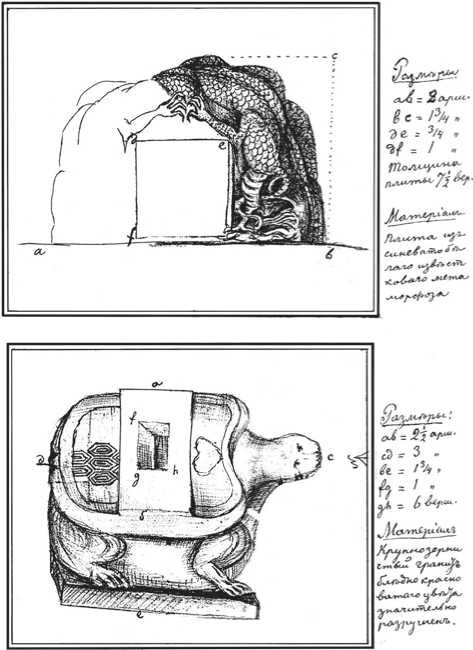

In 2019, 155 years have passed since the first publication of information about a stone tortoise, a unique object of the cultural heritage of the 13th century, discovered in the territory of the future village of Nikolskoye (now the city of Ussuriysk), in the Primorye. The monument was found by the mining engineer I.A. Lopatin in 1864 (Lopatin, 1864). In the work “Some Information on 49 Ancient Localities in the Amur Land”, he published drawings of the tortoise, the slab, and the bas-relief representing two dragons, along with information on their location—“north of the earthen fortification” (1869: 5), as well as detailed drawings of the sculptures, with sizes, indicating that the tortoise with a stele on its back was made of coarse, pale red granite, and the slab and bas-relief were made of metamorphic bluish-white limestone (Ibid.: 6).

In the 19th century, in Ussuriysk, two stone tortoises (including the one described in this article)* and several stone sculptures of soldiers, officials, lions, and rams, accompanying the burials of nobles, were discovered. Since the discovery of these statues, information about them has been very confused; erroneous data continue to be reproduced in various publications (Busse, Kropotkin, 1908; Dryakhlov, Romanov, Chalenko, 2006), despite the fact that scholars have published exact descriptions of the monuments (Okladnikov, 1959; Okladnikov, Derevianko, 1973; Zabelina, 1960; Larichev, 1966; Vorobiev, 1975, 1983). This study provides information about the Ussuriysk tortoise from all known sources, attempts to connect this burial complex with the name of Puxian

Wannu, who ruled in Primorye in the 13th century, and presents the information from the diaries of F.F. Busse about the excavation of a mound under the figure of the tortoise in 1885, and about kurgan No. 2, near the tortoise, excavated in 1889 (1885a, b; 1889).

History of the discovery of, and research on, the Ussuriysk stone tortoise

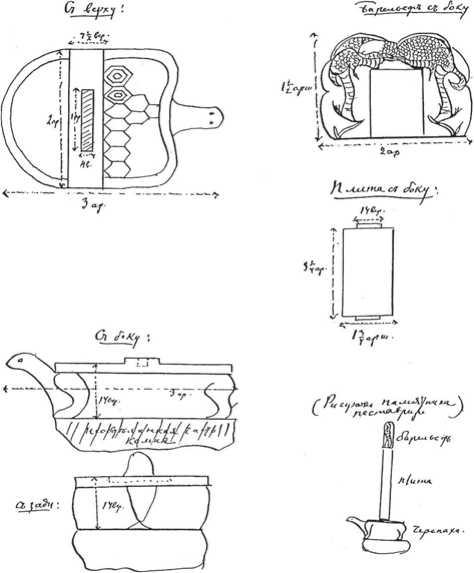

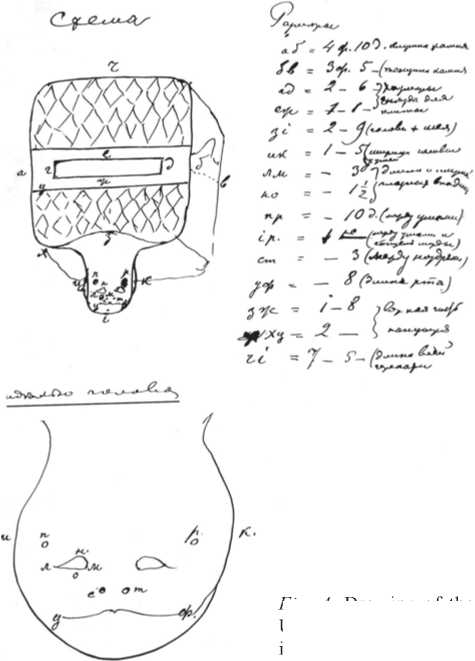

The stone tortoise that is the subject of this study is a reptile sculpture standing on a pedestal about 15 cm high, both being made of pink granite (Fig. 1). The length of the tortoise’s body is 224 cm; the maximum width is 144 cm; the height is 65 cm, and the weight is not less than 6 tons (400 poods) (Busse, 1885a) (Fig. 2–4). The tortoise is represented very realistically, with its head stretched forward and raised upward on a powerful neck. It seems that the body of the tortoise is slightly pressed down by the stele, which was inserted into a hole in its back measuring 75 × 32 cm, with a depth of 20 cm, in the central part of the shell (Fig. 5). Although the tortoise’s body looks pressed, it is noticeable that the limbs are bent resting on the surface, and the paws show resistance to gravity. The back of the tortoise is protected by the shell, with pecked hexagons in the form of symmetrical horn shields imitating concentric annual rings. The tail protrudes from under the shell in the back of the sculpture. All the details of the sculpture are well elaborated. The head is round and elongated; eyes “looking” at the sky are engraved in the upper part of the head. The nostrils are marked by two recesses or holes; the mouth is rendered by well-elaborated semi-oval. There is a recess (urn)—the third eye, which symbolizes the spiritual essence, on the forehead of the tortoise.

Lopatin pointed out that no inscriptions were found on the stele, nor on its top with the dragons. According to Busse, a large stone slab lay under the foundations of the church; according to the peasants who built the church, it had constituted the vertical part of the monument with the tortoise at its base (1889: Fol. 5). This slab was later mentioned by A.Z. Fedorov: it had been located under the bell-tower of the old wooden church, but when the church was later moved to the village of Novo-Nikolskoye in 1914, Father Pavel Michurin found the slab and placed it in the porch of the newly built stone church, where it was clearly visible. Fedorov examined this slab when it was removed from under the bell-tower, and did not find any inscriptions on it. The absence of inscriptions was also confirmed by Father Pavel Michurin (Fedorov, 1916: 19).

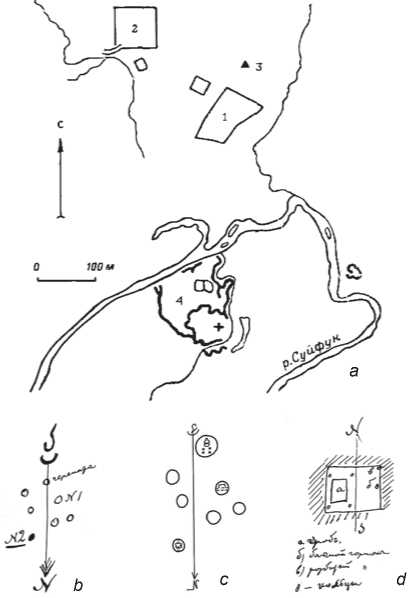

The sculpture of the tortoise was found in the area northwest of the ancient fortification (Southern Ussuriysk fortified settlement) (Fig. 6, a), on a hill 10 m in diameter and 1.5 m high, which was located on the south side of a group of six kurgans (Fig. 6, b, c). The animal’s head was facing south; that is, the kurgans were located behind the tortoise. The sculpture was placed, not in the center of the kurgan, but closer to its southern edge (Busse, 1885a: Fol. 76). During the inspection by Busse, the back part of the sculpture, oriented to the north, and a section of tortoise’s back, were under the ground. Two holes were visible to the north of the figure. These were the remains of the underground passage, which the robbers had made to penetrate into the mound under the tortoise. This resulted in the stone statue’s sinking. In his diary, Busse indicated that the tortoise was located on the southern edge of the kurgan, which was 7 sazhens* in diameter and 5 feet high, and he wrote all measurement results on the attached drawing (1885a: Fol. 76–77).

In 1885, owing to the threat of destruction of the hill where the tortoise was standing, F.F. Busse and V.F. Mikhailovsky transported the statue to the public garden in the village of Nikolskoye. Busse described the process of excavating and transporting the figure in detail (1885b: Fol. 71–74). He used the method of excavation pits and established the stratigraphy of the kurgan: a thin layer of sod, clay, and pieces of black tile at a depth of 30 cm. The thickness of the layer with such fragments in the western part of the mound reached 120 cm. The sterile soil was yellow clay, from which the mound, of regular hemispherical shape lined with halves of bricks along the edge (except for the southern side), was made. The collected material evidence included mainly fragments of tiles, as well as fragments of end-disks with images of flowers and dragons, nails, and an arrowhead. On the northern side, behind the statue, flat hewn stone measuring 60 × 50 × 23 cm was discovered.

Notably, the methods of excavation and engineering solutions to the problem of transporting the monument were well thought-out: a sled had to be moved under the statue. For this purpose, two trenches were made to a depth of 2 feet** on two sides (east and west) below the base of the sculpture. Then, supporting logs were brought under the figure, 2/3 of the soil was removed, and only after that was the sled of five logs pulled up to the sculpture. Using the labor of 40 peasants, the tortoise was placed on the sled, which was harnessed to 11 pairs of bulls. Work on the study of the kurgan under the tortoise ceased with the beginning of frost in late October. Mikhailovsky was entrusted with continuing the excavations, but he could not proceed, burdened with other affairs.

The study of the kurgan was continued under the leadership of Busse only in 1889. The works resumed owing to the construction of peasant houses in the immediate vicinity of the archaeological site, and the setting of a cross 20 meters east of it, which indicated the

Fig. 1 . Sculpture of the Ussuriysk stone tortoise. Photograph by the author .

GceJKOb пайщика.

Fig. 3 . Drawing of the monument made by F.F. Busse (1885a).

Fig. 2 . Drawings of the tortoise, stele, and top made by I.A. Lopatin in 1864 (Lopatin, 1869).

location of the future church. The goal of the excavations was to find a burial in a crypt under the kurgan. To achieve that, a well 1.2 m deep and measuring 1.8 × 2.7 m was dug under the tortoise. According to Busse, a shrine under a tiled roof with clay decorations stood on top of the mound, and the tortoise was inside the shrine. Judging by numerous fragments of tile in its entire thickness, the kurgan was made on the site of a destroyed dwelling (Busse, 1889: Fol. 74–76). The excavation report, presented by Busse at a meeting of the Society for the Study of the Amur Region, said that there was no crypt or grave inside the kurgan. The kurgan, of regular hemispherical shape, was constructed of local yellowish clay. The tortoise was placed, without a foundation pit, a

Fig. 4 . Drawing of the Ussuriysk tortoise with indicated sizes, made by

F.F. Busse (1885a).

Fig. 5 . Drawings of the top and tortoise made by I.A. Lopatin in 1868 (Busse, 1885a).

little south of the center, and there was a small shrine on independent posts behind it (Ibid.: Fol. 13–14).

According to the description of the excavations, the tortoise stood on a platform about 10 m in diameter and about 1 m high. On the southern side, a pathway with an area of 2.5 m2 was made of seven bricks laid with their wide sides to each other in one row. A “belt” of halves of gray bricks was made along other sides of the platform. The tortoise was oriented with its head to the south. A tiled roof decorated with bas-reliefs of horned dragons and end-disks with floral ornamentation was built over the tortoise. The roof was supported by wooden columns, which rested on four stone bases. This structure covered an area of about 5 m2 (2.25 × 2.25 m) and was probably 4 m high. In its architecture it could have resembled a pagoda or open pavilion.

Six kurgans were located next to the tortoise (Fig. 6, b, c). Busse drew a line from north to south across the hill with the tortoise, conventionally dividing the kurgans into two groups—western and eastern. The kurgans of the western group almost touched each other, and made up a triangle. The kurgans of the eastern group (it was called “the tortoise group”) were located in a meridional direction. The northern kurgan (No. 2) of this group, with traces of cremation, was excavated by Busse in 1889. It was located 40 m from the statue. In plan view, the kurgan had the form of a round embankment with a diameter slightly exceeding 8 m and a height of about 1 m. At a depth of 60 cm from its day surface, a square-shaped grave pit measuring 2.25 × 2.0 m and 1.05 m deep was found. At its edges, it was lined with wood, the remains of which could be seen as a black strip. A layer of gray clay up to 10 cm thick covered the bottom of the pit. A wooden box-coffin measuring 62 × 34 cm (see Fig. 6, d) was found at a depth of 63 cm inside the pit, 30 cm from its western wall. This box did not have a lid. It was made of rough split boards (battens), which were coated with earth on both sides. The boards were not fastened at the corners. Most likely, they covered the walls of the pit, which was used as a coffin or urn. In his report, Busse wrote, “Both the bottom and walls of the box were covered with a 5 cm layer of black paste similar in composition to that which was found in the grave pit. The same layer filled the entire space of the box. It is very likely that the whole grave pit was filled with this layer after placing

Fig. 6 . Plan of the ancient fortifications and tombs in the vicinity of Ussuriysk: 1 – Southern Ussuriysk fortified settlement, 2 – Western Ussuriysk fortified settlement, 3 – location of the Ussuriysk tortoise, 4 – Krasny Yar fortified settlement (Busse, Kropotkin, 1908) ( a ); location of kurgans near the Ussuriysk tortoise (Busse, 1889, 1893) ( b , c ); plan of kurgan No. 2 (Busse, 1889) ( d ).

the remains of the deceased inside. A large number of golden spangles was found in that layer. There was a large amount of charcoal with clay inside the coffin, in its upper part. Possibly, these could have been the remains of the coffin lid. The fragments of human bones with traces of being in the fire, along with black oily paste (remains of cremation), were below. Iron staples with rings were found on the external surface of the box at the corners. Iron nails were discovered in the process of unearthing the grave pit. A gray pear-shaped ceramic vase about 23 cm high filled with black paste (burnt decayed bone) with small fragments of bones was at the bottom of the pit, near the middle of the eastern wall. An identical vase with similar content, but apparently broken during the burial, was found in the northeastern corner. Clods of burnt decayed bone, which might have not fit into them, were located between these vases. The bottom of the grave pit consisted of a layer of gray clay, 10–12 cm thick” (1893: Fol. 17).

The features of this burial suggest that the body of the deceased was burned elsewhere. Then, the ashes were placed in a wooden urn and lowered into the grave pit. Ceramic urns with ashes of two more deceased were placed nearby. After that, everything was covered with the remains from the cremation that did not fit into the urns, up to the level of the upper part of the grave pit. After that, the burial mound was made.

Other two kurgans of the tortoise group were excavated in 1889 by V.U. Ulyanitsky. Unfortunately, despite the written promise that Ulyanitsky gave to Busse, he did not submit to the journal the records of the excavations and the collection of antiquities which he found. Busse wrote in his memoirs about the excavations of the kurgan closest to the tortoise and territory to the west of it, done by Ulyanitsky, “He made a deep trench from W to E, at a depth of about a foot below the level of the surrounding area, and found a plank and clods of oily black paste under it, identical to the paste that I found in another kurgan. Further excavations to the south and north up to the level of the plank and deeper, as I recall, did not reveal any remnants of antiquity. As for the other kurgans, I have no information about the results of Ulyanitsky” (1893: Fol. 17). It follows from this description that there was a wooden urn in the kurgan, where the remains of the human skeleton had been placed after cremation.

Records of excavations by Busse and drawings by Lopatin make it possible to conclude that a Jurchen clan cemetery with the burial of a noble was in the place of the kurgans. The “path of the spirits”, marked by stone statues of people and animals, had to depart from the grave of the noble. In China, since ancient times, clan cemeteries always began with constructing the “path of the spirits” (Lin Yun, 1992: 34). The stele on the tortoise was set on the “path of the spirits”, that is, at the other end of the road.

Historical context of the find

The stylistic features of the stone tortoise and the top on its stele leave no doubt that the figures were made in the 13th century. This conclusion is confirmed by the Chinese scholar Lin Yun, who drew attention to the fact that the legs in all early sculptures of tortoises (for example, near the grave of Liu Xu of the Northern Wei Dynasty) were parallel to the ground; while in Jin tortoises, the legs seem to rest with their front part against the pedestal. Shell plates of the Early Jin tortoises were represented as elongated hexagons with their long sides across the shell, while on the Ussuriysk tortoise, they form a horizontal pattern. Differences are also observed in the shape of the top on the stele. For example, the tops dated to the 12th century have the shape of five-sided scepters—plates with rounded ends; while the top found near the Ussuriysk tortoise was rectangular (Lin Yun, 1992: 40).

All scholars have observed that there were no inscriptions on the stele nor on the top of the Ussuriysk tortoise. This can be explained by the possibility that the clan mausoleum had been prepared in advance, and the person for whom it was intended was never buried in it. According to the written sources of the 13th century, the key historical figure in this land was Puxian Wannu—the founder of the Jurchen state of Eastern Xia (1215–1233). Today, it is reliably known that the Upper capital of this state (the town of Kaiyuan) was located within the boundaries of the Krasny Yar fortified settlement (Artemieva, 2008). Puxian Wannu was first mentioned in historical chronicles in connection with the events of 1215. Being the commander of the Jin forces in Liaodong at the time, and fearing the capture of the empire by the Mongols, Puxian Wannu seceded from the Jin dynasty, declared himself the ruler of the new state Da Zhen (“Great Zhen”), and accepted the name of Tiantai (“Celestial Quietude”). These historical events played a major role both in the life of the Jurchen ethnic group, and in the political and economic life of Primorye. In the initial period of the Great Zhen State, the residence of Puxian Wannu was located in Liaoyangfu, the eastern capital of Jin. Wannu’s external policy was aimed at maintaining independence from the Mongols. His campaigns in the neighboring lands did not bring victories. In 1214, taking advantage of the absence of Wannu, the ruler of the Khitan state of Eastern Liao Yelü Liuge captured the Eastern capital with the support of the Mongols, and took Wannu’s wife and relatives prisoners. Caught in a hostile environment, Wannu marched with his army of 100,000 to the east to Helan County, and further to the northeast to Primorye, where he created the state of Dongxia (Eastern Xia) and declared himself its ruler. In order to keep peace on the borders of the state and gain time to prepare for war, Puxian Wannu formally expressed submission to the Mongols and sent his son

Tege to Genghis Khan. Eastern Xia established relations with Goryeo. Thanks to a delicate diplomatic game on the part of Puxian Wannu, the Eastern Xia state lasted until 1233. That year, the Mongol troops, passing through the territory of the Goryeo State, captured the southern capital of Eastern Xia, where Puxian Wannu was at that time. In 1233, Puxian Wannu was captured, and the Mongol troops retreated, leaving 100 or more horsemen in Eastern Xia (Wang Shenrong, Zhao Mingqi, 1990; Zheng Ming, 1985; Ivliev, 1990, 1993). There is no information on the place or circumstances of the burial of Puxian Wannu. There is only the information that in 1233 the ruler of the Eastern Xia State was captured by the Yuan troops in the Southern capital (the Chengzishan fortified settlement) (Zhao Mingqi, 1986). This probably explains the absence of a grave with a stone coffin in the kurgan next to the tortoise and inscriptions on the stele.